C. Rocío Álamo-Herrera a, María Clara Arteaga a, *, Rafael Bello-Bedoy b

a Centro de Investigación Científica y de Educación Superior de Ensenada, Departamento de Biología de la Conservación, Carretera Tijuana-Ensenada # 3918, Zona Playitas, 22860 Ensenada, Baja California, Mexico

b Universidad Autónoma de Baja California, Facultad de Ciencias, Carretera Transpeninsular # 3917, Colonia Playitas, 22860 Ensenada, Baja California, Mexico

*Corresponding author: arteaga@cicese.mx (M.C. Arteaga)

Received: 28 February 2024; accepted: 01 July 2024

Abstract

Tri-trophic interactions between plants, herbivores, and parasitoids are a valuable model for studying how they influence the distribution of genetic diversity and phenotypic variability of the species involved. This study examines the taxonomic, morphological, and genetic diversity of parasitoid wasps involved in the Yucca–Tegeticula interaction on the Baja California Peninsula. We surveyed 35 locations across the peninsula and collected 119 parasitoid wasps. Of these, 114 were adults, while the remaining 5 were in the pupal stage. Our study identified 2 genera of wasps: Bassus sp. (Ichneumonidae; n = 8) and Digonogastra sp. (Brachonidae; n = 111). Moreover, we found moderate levels of genetic diversity within the Digonogastra population across the peninsula. Additionally, this population constitutes a single panmictic group with indications of historical demographic expansion. Phenotypically, we identified sexual dimorphism and variation associated with its different hosts and environmental heterogeneity Digonogastra’s geographical range.

Keywords: Baja California Peninsula; Genetic structure; Host-association; Morphometrics; Tri-trophic interactions

© 2024 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Biología. Este es un artículo Open Access bajo la licencia CC BY-NC-ND

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Diversidad genética y variación fenotípica en una avispa parasitoide involucrada en la interacción entre yucas y sus polillas polinizadoras

Resumen

Las interacciones tritróficas entre plantas, herbívoros y parasitoides son un modelo valioso para estudiar cómo influyen en la distribución de la diversidad genética y la variabilidad fenotípica de las especies involucradas. Este estudio examinó la diversidad taxonómica, morfológica y genética de avispas parasitoides en la interacción Yucca-Tegeticula en la Península de Baja California. El estudio se realizó en 35 localidades recolectando 119 avispas parasitoides; 114 adultos y 5 pupas. Se identificaron 2 géneros de avispas: Bassus sp. (Ichneumonidae; n = 8) y Digonogastra sp. (Brachonidae; n = 111). Se encontraron niveles moderados de diversidad genética dentro de la población de Digonogastra en toda la península, constituyendo un único grupo panmítico con indicios de expansión demográfica histórica. Fenotípicamente, identificamos dimorfismo sexual y variación asociada con sus diferentes hospederos y la heterogeneidad ambiental a lo largo de la distribución geográfica de Digonogastra.

Palabras clave: Península de Baja California; Estructura genética; Asociación al hospedero; Morfometría; Interacción tri-trófica

Introduction

Tritrophic interactions between plants, herbivores, and parasitoids have become pivotal to understanding species diversity (Abdala-Roberts et al., 2019; Godfray, 1994; Singer & Stireman, 2005). Parasitoids maintain an antagonistic relationship with insect herbivores by depositing their eggs inside or on them, ultimately leading to the death of their host (Godfray, 1994; Quicke, 2015; Resh & Cardé, 2009). These parasitoids serve as an indirect defense for plants, controlling herbivore population levels (Abdala-Roberts et al., 2019; Cuautle & Rico-Gray, 2003; Heil, 2008). Plants attract parasitoids by emitting chemical signals that indicate the presence of herbivores, which enables parasitoids to locate their prey, thus establishing mutually beneficial interactions (Heil, 2008; Kappers et al., 2011; Takabayashi & Dicke, 1996).

Multiple studies have explored how interactions among organisms affect the genetic and phenotypic variation within species (e.g., Agrawal, 2001; Carmona et al., 2015). For instance, biotic interactions may differ geographically, resulting in local selection processes and differentiation of parasitoid populations (Althoff & Thompson, 2001; Kankare et al., 2005; Stireman et al., 2005). Environmental factors or geographical distances can also determine the distribution of these variations (Althoff, 2008; Lozier et al., 2009; Stireman et al., 2005). For example, the genetic population structure of the wasp Cotesia congregata Say, 1836 (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) is related to the different plant-hosts with which it interacts (Karns, 2009). Conversely, genetic diversity in the parasitoid wasp Eusandalum sp. Ratzeburg, 1852 (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) is primarily associated with its broad geographical distribution rather than the species it interacts with (Althoff, 2008).

The interaction between Yucca Linnaeus plants, moths of the family Prodoxidae and associated parasitoids have been recorded (Althoff, 2008; Pellmyr, 2003). In this tritrophic interaction, the female moth visits Yucca flowers and lays her eggs in the ovary. Subsequently, she pollinates the stigma by depositing pollen, ensuring the formation of fruits that the moth larvae will feed on (Engelmann, 1872). During fruit production, female parasitoid wasps use their ovipositors to lay eggs on moth larvae inside fruits, paralyzing the larvae (Force & Thompson, 1984). The wasp larva feeds on the host, completes its development, and emerges from the fruit as an adult (Althoff, 2008; Crabb & Pellmyr, 2006). The interaction between Yuccas and moths have driven differentiation and diversification processes in the involved species (Althoff et al., 2012; Althoff & Segraves, 2022; Pellmyr & Leebens-Mack, 1999). However, little is known about the third trophic level of this relationship, which consists of parasitoid wasps that interact with the moth (their food source) and the plant (their shelter until hatching).

In the Baja California Peninsula, 3 Yucca species and 2 Tegeticula Zeller, 1873 species are distributed allopatrically. Yucca schidigera Roezl ex Ortgies (Asparagales: Asparagaceae) occurs in the northern part of the peninsula and is pollinated by Tegeticula mojavella Pellmyr, 1999 (Lepidoptera: Prodoxidae). Yucca valida Brandegee (Asparagales: Asparagaceae) is distributed in the central region, whereas Yucca capensis L.W. Lenz, 1998 (Asparagales: Asparagaceae) occurs in the southern part of the peninsula. Both Y. valida and Y. capensis are pollinated by Tegeticula baja Pellmyr, Balcázar-Lara, Segraves, Althoff & Littlefield, 2008 (Lepidoptera: Prodoxidae; Lenz, 1998; Turner et al., 1995). Furthermore, a region of hybrid populations of Y. valida and Y. capensis has been identified, both pollinated by T. baja (Arteaga et al., 2020). However, there are no previous records of parasitoid wasps associated with T. baja or T. mojavella populations in the Baja California Peninsula. This study aims to identify the genera of parasitic wasps associated with Tegeticula species in the peninsula. We also investigate whether the use of different hosts, such as T. mojavella and T. baja, and the environmental distribution of the wasps lead to phenotypic and genetic differentiation in the wasp populations.

Materials and methods

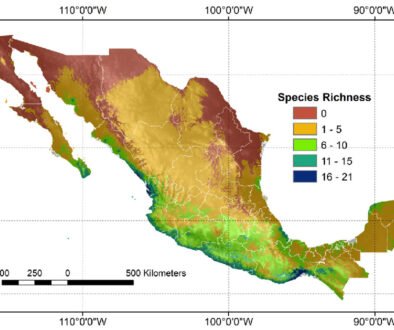

We visited 35 locations in the Baja California Peninsula, following the distribution of the Yucca species and their pollinators T. mojavella and T. baja (Fig. 1A, Table S1). Specifically, we surveyed 12 locations in the northern section of the peninsula, where Yucca schidigera occurs, within forest habitats of Sierra Juárez (N = 6), Sierra San Pedro Mártir (N = 4), and Chaparral (N = 2). We visited 11 locations within the central desert of the peninsula where Yucca valida are distributed. Finally, we collected samples from 12 locations in the south section of the peninsula. Eight locations were in the coastal plains of the Magdalena Plains region, where populations of Y. valida x Y. capensis are found. The remaining 4 locations were in the deciduous lowland forest of the Cape Region, where Y. capensis populations are present.

Each location was visited once between 2013 to 2015, during the fruiting season of the Yucca species. We selected approximately 10 trees per location, gathering 3 to 5 fruits from each tree. The mature fruits were collected directly from Yucca trees and placed individually within 500 ml plastic cups with mesh netting lids. Fruits were transported to the laboratory and stored in rooms at environmental conditions (approximately 25°C and 60% relative humidity). For 2 weeks, we checked each plastic cup daily for adult wasps. All adult wasps that emerged from the fruits were collected and placed in 20 ml glass vials. Following another 2 weeks, we dissected the fruits to obtain wasps pupae. All wasps were preserved in glass vials with 96% ethanol and labeled with locality and host plant species. Adult individuals were observed with a Nikon SMZ745-T stereomicroscope equipped with Lumenera’s INFINITY digital camera, and identified to genus taxonomic level using the dichotomous key provided by Sánchez et al. (1998). Two genera of parasitoid wasps from the Braconidae family were identified (Fig. 2): Bassus Fabricius, 1804 and Digonogastra Viereck, 1912.

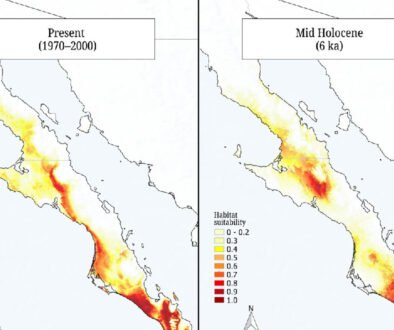

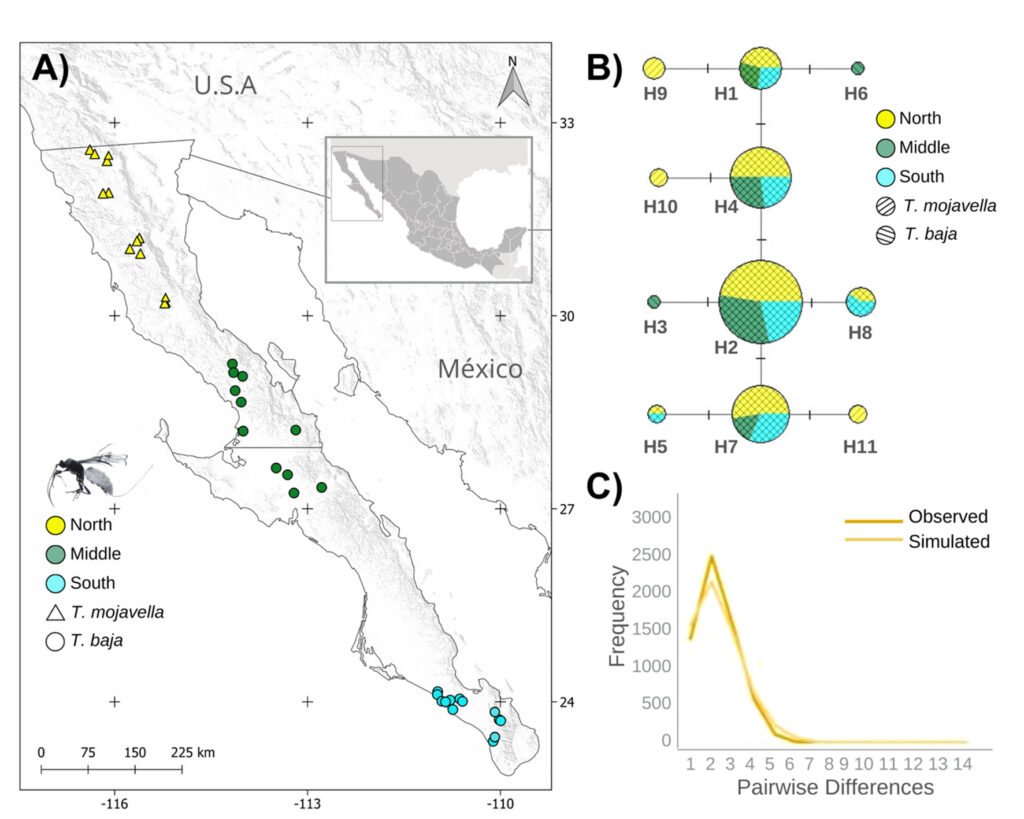

Figure 1. A, Localities sampled of Digonogastra sp. in the Baja California Peninsula. The geographical distribution is marked using colors and the host moth species is indicated whit shapes; B, haplotype network. The geographical distribution is marked using colors and the host moth species with lines; C, graph depicting the observed and simulated distribution of paired sequence differences.

Figure 2. The genera of parasitoid wasps sampled from yucca fruits in the Baja California Peninsula. On the upper side is the genus Digonogastra; on the bottom is Bassus.

DNA extraction and molecular marker amplification. We extracted DNA from 119 wasps using the commercial Qiagen DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit. The sample consisted of 114 adult individuals and 5 in the pupal stage. A fragment of the Cytochrome Oxidase subunit I (COI) marker was amplified via PCR using the universal primers for invertebrates described by Folmer et al. (1994); LCO1490 (5’-GGTCAACAAATCATAAAGATATTGG-3’) and HCO2198 (5’-TAAACTTCAGGGTG ACCAAAAAATCA-3’). The PCR mixture included 5 µl of Buffer (1x), 1.5 µl of MgCL (2.5mM), 0.3 µl of dNTPs (0.16mM), 0.6 µl of each primer at 10 µM, 0.2 µl of Taq polymerase (1 unit), 1 µl of DNA, and 5.8 µl of molecular-grade water, resulting in a 15 µl reaction volume.

The thermal cycler was set up with the following conditions: an initial denaturation at 94 ºC for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 ºC for 1 min, annealing at 50 ºC for 1 min, and extension at 68 ºC for 1 min. A final elongation step was performed at 72 ºC for 5 min. Amplification quality was confirmed using 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. The PCR products were sequenced by SeqXcel (www.seqxcel.com) for further analysis.

Genetic diversity and population genetic structure. The sequences were visualized, aligned, and edited using the BioEdit software (Hall, 1999). Sequences from individuals identified morphologically were submitted to BLAST to confirm the parasitoid genus (Blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). The sample size of Digonogastra sp. (N = 111) allowed for diversity and population structure analysis. The genetic diversity of Digonogastra species was assessed using DNAsp software (Rozas et al., 2003). This involved calculating the number of haplotypes, haplotype diversity, and nucleotide diversity (Nei & Li, 1979; Nei, 1987). To investigate the genealogical relationships among the identified haplotypes, we constructed a haplotype network using the Median-Joining method in NETWORK 5.0 software (Bandelt et al., 1999). We constructed a phylogenetic tree using the haplotypes obtained for Digonogastra sp. to determine whether the detected diversity in the Baja California Peninsula is unique to this region or present elsewhere. We included sequences available in the NCBI from Canada. The genera Alabagrus (Sharkey & Chapman, Unpublished; GenBank: MF361682.1) and Cotesia (Hebert et al., 2016) were employed as outgroups. The tree was constructed using the Maximum Likelihood method, with 1000 bootstrap replicates and the HKY+I substitution model, which showed the best fit to the data (highest AIC value), as determined by the jModelTest program (Darriba et al., 2012).

To assess genetic differentiation of Digonogastra spp. across its geographical distribution in the peninsula, we conducted 3 Molecular Variance Analyses (AMOVA). First, we examined how geographical distances affected the distribution of genetic diversity. We divided the data into 3 categories based on their location in the peninsula: north, center, and south (Fig. 1A). Then, we assessed whether genetic differentiation was due to environmental factors, grouping the data based on their ecoregion of origin. We based our categorization on the ecoregions proposed by Gonzales-Abraham et al. (2010). Lastly, our third analysis examined whether genetic differentiation was related to the host, grouping the data based on the host moths, T. mojavella and T. baja. The ARLEQUIN software (Excoffier et al., 2005) was employed for these analyses.

We evaluated historical demographic changes in the wasp population using the pairwise sequence differences distribution analysis (mismatch analysis) performed in the ARLEQUIN software. The shape of the mismatch distribution is used to infer whether a population expansion has occurred (Rogers & Harpending, 1992). A unimodal distribution indicates population expansion, while a multimodal distribution suggests a stable population size. Additionally, the sum of squared deviations (SSD) is employed to validate the expansion model (Navascués et al., 2006). A significant SSD (p < 0.05) rejects the population expansion model.

Phenotypic variation. Phenotypic variation of the parasitoid wasps was evaluated by measuring 106 adult

individuals of the Digonogastra genus (excluding individuals in the pupal stage). No morphometric analyses were conducted for Bassus specimens due to their small sample size (N = 8). Measurements of the 106 adults were conducted with Infinity Analyze software (Lumenera, Canadá), calibrated in millimeters and verified with a conventional ruler. We measured 18 external morphological characters of the adult individuals (Table 1). Measurements were taken on the left side of the individuals and included the length from the head to the end of the last metasoma segment, the scape width, antenna length, mesosoma (thorax) and metasoma (abdomen) width and length, femur width, total leg length, anterior wing length, and the length of 5 wing vein components: C+SC+R, 1RS, (RS+M)a, 2RS, and r-rs. For females, we also measured the length and width of the ovipositor and the length of the ovipositor apex (Table 1). We calculated the mean, standard deviation, and coefficient of variation of each measured character. A correlation matrix was created using the Pearson Correlation Coefficient (r) between pairs of characters, determining the significance values (p) for each correlation. All morphometric measurements were analyzed with JMP 5.01 software (SAS Cary, New Jersey, USA).

We assessed 3 potential sources of variation for the phenotypic differentiation among parasitoid wasps in the Baja California Peninsula: sexual dimorphism, the ecoregions in which they are distributed, and the host species of Tegeticula moths. We conducted a Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA) for each factor using all measured characters. We also performed an Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to determine which trait contributes significantly to phenotypic differences. Each wasp was assigned to an ecoregion based on its geographical origin (Gonzales-Abraham et al., 2010). The wasps were found in 6 ecoregions: Sierra Juárez, Sierra San Pedro Mártir, Chaparral, Central Desert, Magdalena Plains, and Cape Lowland Forest.

Results

We collected a total of 119 parasitoid wasps from 35 locations across the Baja California Peninsula (Fig. 1A, Table S1). Two genera of parasitoid wasps belonging to the Braconidae family were collected: Bassus and Digonogastra. Eight female individuals of Bassus sp. (6.7%) emerged from fruits in 2 different locations. Seven Bassus specimens were collected in Y. valida fruits, while 1 emerged from Y. capensis. All these fruits contained T. baja larvae. In contrast, we collected 111 Digonogastra individuals (93.3%), with 68 males and 38 females from 33 different sites across 32.58° to 23.38° N latitude. Out of these, 57 individuals of Digonogastra sp. emerged from Y. schidigera fruits where T. mojavella was also found. The remaining 54 individuals were found in Y. valida, Y. valida x Y. capensis, and Y. capensis fruits, where T. baja larvae were also present.

Table 1

Mean (M), standard deviation (SD), and coefficient of variation in percentage (CV) of the evaluated morphological traits in female and male individuals of Digonogastra sp. in the Baja California Peninsula. The results of the analysis of variance (ANOVA) performed for sexual dimorphism (S), ecoregions (E), and host (H) are presented with significance levels denoted as follows: p > 0.05 (ns), p < 0.05 (*), and p < 0.0001 (***).

| Trait | Female | Male | ANOVA | ||||||

| M | SD | CV | M | SD | CV | S | E | H | |

| Body length: | 9.03 | 1.29 | 14.24 | 7.34 | 1.47 | 20.04 | *** | * | ns |

| Antenna: | |||||||||

| Total length | 6.88 | 0.73 | 10.58 | 6.16 | 1.08 | 17.52 | *** | * | ns |

| Escapo width | 0.24 | 0.03 | 12.61 | 0.19 | 0.04 | 22.92 | *** | ns | ns |

| Leg: | |||||||||

| Total length | 6.97 | 0.90 | 12.96 | 5.21 | 1.08 | 20.67 | *** | * | ns |

| Femur width | 0.52 | 0.06 | 12.23 | 0.36 | 0.08 | 22.93 | *** | * | ns |

| Mesosoma: | |||||||||

| Lateral width | 2.17 | 0.32 | 14.54 | 1.61 | 0.34 | 21.11 | *** | ns | ns |

| Lateral length | 3.17 | 0.45 | 14.08 | 2.46 | 0.58 | 23.59 | *** | * | ns |

| Metasoma: | |||||||||

| Lateral width | 2.14 | 0.56 | 26.32 | 1.33 | 0.44 | 33.15 | *** | * | ns |

| Lateral length | 4.84 | 0.81 | 16.83 | 4.03 | 0.86 | 21.20 | *** | * | ns |

| Wing: | |||||||||

| Total length | 8.47 | 0.95 | 11.19 | 6.30 | 1.26 | 19.96 | *** | * | ns |

| C+SC+R length | 3.99 | 0.48 | 12.14 | 3.03 | 0.62 | 20.62 | *** | * | ns |

| 1RS length | 0.26 | 0.04 | 15.15 | 0.21 | 0.05 | 23.26 | *** | ns | ns |

| (RS+M)a length | 1.00 | 0.13 | 12.46 | 0.70 | 0.15 | 21.33 | *** | * | ns |

| 2RS length | 0.69 | 0.10 | 13.98 | 0.51 | 0.10 | 18.78 | *** | * | ns |

| r-rs length | 0.29 | 0.05 | 17.53 | 0.21 | 0.05 | 21.47 | *** | * | ns |

| Ovipositor: | |||||||||

| Total length | 8.37 | 1.07 | 12.84 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ns | ns |

| Lateral width | 0.06 | 0.01 | 10.54 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ns | ns |

| Apex length | 0.36 | 0.05 | 14.22 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ns | ns |

Genetic diversity and population genetic structure. We obtained a 632 bp sequence for each of the 8 individuals of Bassus sp. These sequences did not exhibit site variability, defining them as a single haplotype. Further analyses were not conducted due to the lack of variation. Compared to NCBI sequences, they showed 97% coverage, an E-value of 0.0, and 97.73% identity with the genus Bassus.

The alignment of the 111 Digonogastra wasps allows us to obtain 563 bp and reveals 7 variable sites. We obtained 100% coverage, 0.0 E-value, and 93.61% identity compared with NCBI sequences. Nucleotide diversity (Pi) for Digonogastra sp. in the peninsula was 0.00228, and haplotype diversity (Hd) was 0.775. The 7 variable sites defined 11 haplotypes. Haplotype 2 was most abundant, followed by haplotypes 4, 7, and 1 (Fig. 1B). Six of the 11 haplotypes were found throughout the entire geographic range, 3 were unique to the northern region, and 2 were only found in the central part of the peninsula. The phylogenetic analysis revealed that 11 haplotypes from the peninsula formed a single clade with 100% support (Fig. S1). This clade was separated from 5 clades found in Canada, although with low bootstrap support (43%).

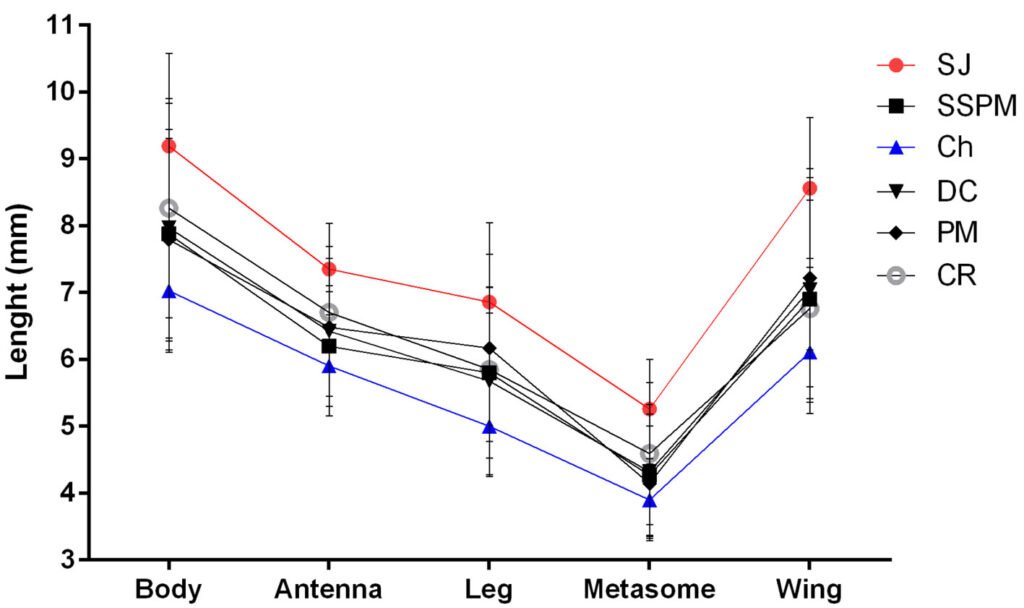

Figure 3. Mean and standard deviation of 5 significantly different traits of Digonogastra sp. among Baja California Peninsula ecoregions. From north to south, they are listed as follows: Sierra Juárez (SJ), Sierra San Pedro Mártir (SSPM), Chaparral (Ch), Central Desert (DC), Magdalena Plains (PM), and Cape Region (CR). Individuals with larger sizes are marked in red, while those with smaller sizes are marked in blue.

The geographical distance did not cause genetic differentiation in Digonogastra sp. individuals (Fst = -0.01319, S.S. = 41.176, p = 0.84360 ± 0.01326). Similarly, no differentiation was found between individuals inhabiting different ecoregions (Fst = -0.01838, S.S. = 38.933, p = 0.05181 ± 0.00599) and individuals parasitizing different host species (Fst = 0.01877, S.S. = 41.853, p = 0.06158 ± 0.00750). Considering that Digonogastra sp. individuals from the peninsula form a single genetic clade, we performed a demographic analysis (i.e., mismatch analysis), including all individuals as a single population. The distribution of paired differences was unimodal, and the SSD test did not reject the expansion hypothesis (p = 0.09).

Phenotypic variation. Digonogastra sp. females had an average body length of 9.03 mm, with their morphological characters showing coefficients of variation between 10% and 27%. Males had an average body length of 7.34 mm, with morphological characters exhibiting coefficients of variation between 17% and 33%. The most variable character was the metasoma width for females and males, with coefficients of variation of 26.32% and 33.15%, respectively. Females exhibited significant correlations between all analyzed traits (r² > 0.6; p < 0.05), except for ovipositor width, ovipositor tip length, and scape width (r² < 0.3; p > 0.05), while males showed significant correlations across all traits (Fig. S2).

Morphological differences between males and females were significant (F test = 5.21, F = 25.74, p < 0.0001), with females being consistently larger in all measured characters (Table 1). Similarly, significant differences were found among individuals from different ecoregions (Wilks’ Lambda = 0.195, F = 1.83, p < 0.0002; Table 1, Fig. 3), with 11 out of 18 characters showing high variation (Table 1). Finally, significant differences observed in the MANOVA (F test = 0.40, F = 1.98, p < 0.027) indicate that the traits of the wasps vary according to the host groups, even though the ANOVA did not detect significant differences in individual traits (Table 1).

Discussion

The taxonomic, genetic, and phenotypic diversity of parasitoid wasps is influenced by environmental and spatial distribution of their populations and hosts (Althoff & Thompson, 2001; Baer et al., 2004; Harrison et al., 2022). Here, we have recorded for the first time Bassus wasps attacking Tegeticula moths. Additionally, we include the first report of a Digonogastra wasps attacking T. baja. The 111 Digonogastra sp. individuals from various environments showed low genetic diversity across the peninsula, suggesting a single panmictic population that had experienced historical demographic expansion. We also identified sexual dimorphism and morphometric variation due to ecoregions and diferent host.

Genetic diversity estimates for Digonogastra sp. in the Baja California Peninsula are moderate (N = 111, 11 haplotypes, Hd = 0.77, pi = 0.00228). Similar genetic diversity values have been reported for other parasitoid wasps in the Braconidae family (Baer et al., 2004; Hufbauer et al., 2004). For Digonogastra sp., we obtained values of reduced nucleotide diversity alongside high haplotype diversity, indicating that population haplotypes are very similar to each other, as shown in our haplotype network (Fig. 1B). This pattern is observed in species that have experienced population expansion events (Roderick, 1996). Individuals from the Baja California Peninsula have different haplotypes than those recorded to the north of the genus’s distribution, and they cluster into a different clade from the haplotypes reported in Canada (Fig. S1). Future sampling in intermediate areas will help determine whether the diversity found in this study is shared with other zones of their distribution or is restricted to this geographic region.

We found no genetic diversity structuring Digo-

nogastra sp. individuals from different geographic areas, ecoregions, or hosts (i.e., Tegeticula spp.) in the Baja California Peninsula. Furthermore, Digonogastra individuals share most of the recorded haplotypes, suggesting a single panmictic population. A similar pattern was observed in the parasitoid wasp Eusandalum sp., which attacked 11 species of Prodoxus spp. moths in a Yucca complex, in the USA (Althoff, 2008). These 2 wasp genera are known for their generalist nature, which may be related to the genetic differentiation pattern across the landscape. Eusandalum sp., in particular, can lay eggs throughout the year and parasitize any available Prodoxus species, which helps to maintain a continuous population across the landscape (Althoff, 2008). Digonogastra has been recorded attacking various Tegeticula and Prodoxus moths (Force & Thompson, 1984), also present in the peninsula (obs. pers; Althoff et al., 2007). Therefore, other potential food sources could contribute to the population connectivity of Digonogastra sp. throughout its distribution. For example, Prodoxus larvae have been observed as a year-round resource (Powell, 1989). However, further studies are needed to confirm the presence of Digonogastra sp. attacking other Tegeticula and Prodoxus species in this region.

The panmictic population of Digonogastra sp. in the Baja California Peninsula exhibited a historical population expansion, as supported by different analyses (Fig. 1C). The close parasitoid-host interaction with Yucca-pollinating moths implies that demographic changes in their hosts (moths) and in the plants can directly affect the demographics of their populations. Previous studies have recorded the influence of glacial and interglacial cycles in the Quaternary on the demographic history of organisms in the Baja California Peninsula (Garrick et al., 2009; Harrington et al., 2018; Nason et al., 2002). Demographic changes have been documented for the 3 Yucca species in this region, and their habitat has expanded since the last interglacial maximum (Alemán et al., 2024; Arteaga et al., 2020; De la Rosa et al., 2020). Since Digonogastra sp. individuals rely on Yucca plant fruits to complete their life cycle, as these fruits host the moth larvae that serve as their food source, the population expansion found in these wasps may be a consequence of the population expansion observed in the plants that host their hosts.

Phenotypic variability and sexual dimorphism of Digonogastra sp. Geographic variation in phenotype is a common factor in insect populations (Stilwell & Fox, 2007, 2009). The spatial structure of this variation can be determined by environmental conditions, genetic composition, and/or ecological interactions (Agrawal, 2001; Resh & Cardé, 2009; Seifert et al., 2022). For Digonogastra sp. in the Baja California Peninsula, our results show phenotypic variability and a high phenotypic correlation among the studied traits (Table 1, Fig. S2). However, the female ovipositor showed low variation and correlation with the other traits, indicating that its variation did not depend closely on the expression of other traits. Females use the ovipositor to pierce the fruit pericarp, access the moth larvae, and lay eggs (Crabb & Pellmyr, 2006; Resh & Cardé, 2009; Vilhelmsen et al., 2001). The function of this trait is closely related to its fitness, as the arrangement of wasp eggs near moth larvae inside the fruit determines their survival by allowing access to their food source. This may favor reduced variation in ovipositor size (Mazer & Damuth, 2001; Pigliucci, 2003).

Like other parasitoid wasps, Digonogastra sp. exhibits sexual dimorphism (Hurlbutt, 1987; Quicke, 2015), with females being larger in all the traits assessed compared to males (Table 1). Sexual dimorphism in Hymenoptera is partly attributed to complementary sex determination (CSD), where fertilized eggs develop into females and unfertilized eggs into males (Quicke, 2015; Resh & Cardé, 2009). Studies on parasitoid wasps have shown that females typically allocate more resources to fertilized eggs (females) than unfertilized ones (males; Ellers & Jervis, 2003; Jervis et al., 2008; Quicke, 2015; Resh & Cardé, 2009; Visser, 1994). Therefore, the variation in size can be explained by the interplay between CSD and the differential allocation of resources during oviposition.

The environmental heterogeneity in which these wasps are distributed in the Baja California Peninsula also affects their phenotypic variation (Fig. 3). Similar patterns have been observed in butterflies, where species distributed across a broad environmental range exhibit greater variation in organism size compared to species with a more restricted environmental distribution (Seifert et al., 2022). The relationship between body size and environmental variability is attributed to the significant influence of the environment on the development and growth of holometabolous insects, considering factors such as temperature, humidity, and nutrition (Davidowitz et al., 2004; Stillwell & Fox, 2007; Wonglersak et al., 2020). Digonogastra sp. wasps from the Baja California Peninsula occur in different ecosystems, including mountainous areas, deserts, and lowland forests, with variable climatic conditions. However, this study did not investigate the environmental factors that may affect morphological differentiation, which is a topic for future research.

Ecological interactions between plants, herbivores, and parasitoids are significant drivers of biological diversity in terrestrial ecosystems (Schoonhoven et al., 2005). The phenotypic variation in Digonogastra sp. is influenced by the interaction between the wasp, the ecoregion and the host. Tritrophic interactions have shown that a favorable environment for plant growth leads to better nutrition for herbivorous insects, enhancing the development and performance of parasitoids (Han et al., 2019; Pekas & Wäckers, 2020; Schoonhoven et al., 2005). These “bottom-up” cascades have been studied and have shown that the nutritional quality of the plant and the host insect plays a critical role in parasitoids. For instance, it has been observed that parasitoid wasps have increased fitness when they inhabit more fertile soils (Pekas & Wäckers, 2020; Sarfraz et al., 2009). This suggests that the different trophic levels may influence the phenotypic diversity of this wasp, namely the plant and herbivore.

In conclusion, our study records for the first time the genus of parasitoid wasps Bassus attacking Tegeticula moths and increases the diversity of hosts attacked by Digonogastra wasps. The genetic diversity of Digonogastra sp. in the Baja California Peninsula is moderate, forming a single panmictic population with signs of historical demographic expansion. Phenotypic variation is influenced by sexual dimorphism, ecoregions, and their host, this highlights the various factors that can shape the phenotype of these parasitoid wasps. The presence of Digonogastra sp. in different ecoregions suggests the influence of ecological interactions on their phenotypic diversity.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Leonardo de la Rosa, Mario Salazar, José Delgadillo, and Darlene van der Heiden for their help with laboratory analysis, technical support, and assistance in the fieldwork. C.R.A.H thanks the Centro de Investigación Científica y Educación Superior de Ensenada (CICESE) and Universidad Autónoma de Baja California (UABC) for offering academic support. This study was supported financially by Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (Conacyt) (CB-2014-01-238843, infra-2014-1-226339). The Rufford Foundation also provided financial support for a part of this study (RSG 13704-1) and the Jiji Foundation. The authors thank the Associate Editor and the anonymous reviewer for their valuable comments. The authors do not have any conflict of interest to declare.

Haplotypes from this study were deposited in the GenBank with accession numbers PQ252653-PQ252665.

References

Abdala-Roberts, L., Puentes, A., Finke, D. L., Marquis, R. J., Montserrat, M., Poelman, E. H. et al. (2019). Tri-trophic interactions: bridging species, communities and ecosystems. Ecology Letters, 22, 2151–2167. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13392

Agrawal, A. A. (2001). Phenotypic plasticity in the interactions and evolution of species. Science, 294, 321–326. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1060701

Althoff, D. M., & Thompson, J. N. (2001). Geographic structure in the searching behaviour of a specialist parasitoid: combining molecular and behavioural approaches. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 14, 406–417. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1420-9101.2001.00286.x

Althoff, D. M., Svensson, G. P., & Pellmyr, O. (2007). The influence of interaction type and feeding location on the phylogeographic structure of the yucca moth community associated with Hesperoyucca whipplei. Molecular Phy-

logenetics and Evolution, 43, 398–406. https://doi.org/10.

1016/j.ympev.2006.10.015

Althoff, D. M. (2008). A test of host-associated differentiation across the ‘parasite continuum’in the tri-trophic interaction among yuccas, bogus yucca moths, and parasitoids. Molecular Ecology, 17, 3917–3927. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03874.x

Althoff, D. M., Segraves, K. A., Smith, C. I., Leebens-Mack, J., & Pellmyr, O. (2012). Geographic isolation trumps coevolution as a driver of yucca and yucca moth diversification. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 62, 898–906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2011.11.024

Althoff, D. M., & Segraves, K. A. (2022). Evolution of antag-

onistic and mutualistic traits in the yucca-yucca moth obligate pollination mutualism. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 35, 100–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/jeb.13967

Arteaga, M. C., Bello-Bedoy, R., & Gasca-Pineda, J. (2020). Hybridization between yuccas from Baja California: Genomic and environmental patterns. Frontiers in Plant Science, 11, 685. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2020.00685

Baer, C. F., Tripp, D. W., Bjorksten, T. A., & Antolin, M. F. (2004). Phylogeography of a parasitoid wasp (Diaeretiella rap-

ae): no evidence of host-associated lineages. Molecular Ecology, 13, 1859–1869. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.

2004.02196.x

Bandelt, H. J., Forster, P., & Röhl, A. (1999). Median-joining networks for inferring intraspecific phylogenies. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 16, 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026036

Carmona, D., Fitzpatrick, C. R., & Johnson, M. T. (2015). Fifty years of co-evolution and beyond: integrating co-evolution from molecules to species. Molecular Ecology, 24, 5315–5329. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.13389

Crabb, B. A., & Pellmyr, O. (2006). Impact of the third trophic level in an obligate mutualism: do yucca plants benefit from parasitoids of yucca moths? International Journal of Plant Sciences, 167, 119–124. https://doi.org/10.1086/497844

Cuautle, M., & Rico-Gray, V. (2003). The effect of wasps and ants on the reproductive success of the extrafloral nectaried plant Turnera ulmifolia (Turneraceae). Functional Ecology, 17, 417–423. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2435.2003.00732.x

Darriba, D., Taboada, G. L., Doallo, R., & Posada, D. (2012). jModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nature Methods, 9, 772. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.2109

Davidowitz, G., D’Amico, L. J., & Nijhout, H. F. (2004). The effects of environmental variation on a mechanism that controls insect body size. Evolutionary Ecology Research, 6, 49–62.

De la Rosa-Conroy, L., Gasca-Pineda, J., Bello-Bedoy, R., Eguiarte, L. E., & Arteaga, M. C. (2020). Genetic patterns and changes in availability of suitable habitat support a colonization history of a North American perennial plant. Plant Biology, 22, 233–242. https://doi.org/10.1111/plb.13053

Ellers, J., & Jervis, M. (2003). Body size and the timing of egg production in parasitoid wasps. Oikos, 102, 164–172. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0706.2003.12285.x

Engelmann, G. (1872). The flower of yucca and its fertilization. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club, 3, 33–33.

Excoffier, L., Laval, G., & Schneider, S. (2005). Arlequin (version 3.0): an integrated software package for population genetics data analysis. Evolutionary Bioinformatics Online, 2005,47–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/117693430500100003

Folmer, O., Hoeh, W. R., Black, M. B., & Vrijenhoek, R. C. (1994). Conserved primers for PCR amplification of mitochondrial DNA from different invertebrate phyla. Molecular Marine Biology and Biotechnology, 3, 294–299.

Force, D. C., & Thompson, M. L. (1984). Parasitoids of the immature stages of several southwestern yucca moths. The Southwestern Naturalist, 29, 45–56. https://doi.org/

10.2307/3670768

Garrick, R. C., Nason, J. D., Meadows, C. A., & Dyer, R. J. (2009). Not just vicariance: phylogeography of a Sonoran Desert euphorb indicates a major role of range expansion along the Baja peninsula. Molecular Ecology, 18, 1916–1931. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04148.x

Godfray, H. C. J. (1994). Parasitoids: behavioral and evolut-

ionary ecology. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

González-Abraham, C. E., Garcillán, P. P., & Ezcurra, E. (2010). Ecorregiones de la península de Baja California: una síntesis. Boletín de la Sociedad Botánica de México, 87, 69–82. https://doi:10.17129/botsci.302

Hall, T. A. (1999). BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symposium Series, 41,95–98.

Han, P., Desneux, N., Becker, C., Larbat, R., Le Bot, J., Adamowicz, S. et al. (2019). Bottom-up effects of irrigation, fertilization and plant resistance on Tuta absoluta: implications for Integrated Pest Management. Journal of Pest Science, 92, 1359–1370. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-018-1066-x

Harrington, S. M., Hollingsworth, B. D., Higham, T. E., & Reeder, T. W. (2018). Pleistocene climatic fluctuations drive isolation and secondary contact in the red diamond rattlesnake (Crotalus ruber) in Baja California. Journal of Biogeography, 45, 64–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.13114

Harrison, K., Tarone, A. M., DeWitt, T., & Medina, R. F. (2022). Predicting the occurrence of host-associated differentiation in parasitic arthropods: a quantitative literature review. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata, 170, 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/eea.13123

Hebert, P. D., Ratnasingham, S., Zakharov, E. V., Telfer, A. C., Levesque-Beaudin, V., Milton, M. A. et al. (2016). Counting animal species with DNA barcodes: Canadian insects. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 371, 20150333. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0333

Heil, M. (2008). Indirect defence via tritrophic interactions.

New Phytologist, 178, 41–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-

8137.2007.02330.x

Hufbauer, R. A., Bogdanowicz, S. M., & Harrison, R. G. (2004). The population genetics of a biological control introduction: mitochondrial DNA and microsatellie variation in native and introduced populations of Aphidus ervi, a parisitoid wasp. Molecular Ecology, 13, 337–348. https://doi.org/10.

1046/j.1365-294X.2003.02084.x

Hurlbutt, B. (1987). Sexual size dimorphism in parasitoid wasps. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 30, 63–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8312.1987.tb00290.x

Jervis, M. A., Ellers, J., & Harvey, J. A. (2008). Resource acquisition, allocation, and utilization in parasitoid reproductive strategies. Annual Review of Entomology, 53,361–385. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ento.53.103106.093

433

Kankare, M., Van Nouhuys, S., & Hanski, I. (2005). Genetic divergence among host-specific cryptic species in Cotesia melitaearum aggregate (Hymenoptera: Braconidae), parasitoids of checkerspot butterflies. Annals of the Entomological Society of America, 98, 382–394. https://doi.org/10.1603/0013-8746(2005)098[0382:GDAHCS]2.0.CO;2

Kappers, I. F., Hoogerbrugge, H., Bouwmeester, H. J., & Dicke, M. (2011). Variation in herbivory-induced volatiles among cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) varieties has consequences for the attraction of carnivorous natural enemies. Journal of Chemical Ecology, 37, 150–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10886-011-9906-7

Karns, G. (2009). Genetic differentiation of the parasitoid, Cotesia congregata (Say), based on host-plant complex (M. Sc. Thesis). Virginia Commonwealth University. VA, USA. https://doi.org/10.25772/1E5V-N037

Lenz, L. W. (1998). Yucca capensis (Agavaceae, Yuccoideae), a new species from Baja California Sur, Mexico. Cactus and Succulent Journal, 70, 289–296.

Lozier, J. D., Roderick, G. K., & Mills, N. J. (2009). Molecular markers reveal strong geographic, but not host associated, genetic differentiation in Aphidius transcaspicus, a parasitoid of the aphid genus Hyalopterus. Bulletin of Entomological Research, 99, 83–96. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007485308006147

Mazer, S. J., & Damuth, J. (2001). Nature and causes of variation. In C. W. Fox, D. A. Roff, & D. J. Fairbairn (Ed). Evolutionary ecology: concepts and case studies (pp. 3–15). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Nason, J. D., Hamrick, J. L., & Fleming, T. H. (2002). Historical vicariance and postglacial colonization effects on the evolution of genetic structure in Lophocereus, a Sonoran Desert columnar cactus. Evolution, 56, 2214–2226. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0014-3820.2002.tb00146.x

Navascués, M., Vaxevanidou, Z., González-Martínez, S. C., Climent, J., Gil, L., & Emerson, B. C. (2006). Chloroplast microsatellites reveal colonization and meta-

population dynamics in the Canary Island pine. Molecular Ecology, 15, 2691–2698. https://doi.org/10.1111/

j.1365-294X.2006.02960.x

Nei, M., & Li, W. H. (1979). Mathematical model for studying genetic variation in terms of restriction endonucleases. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 76, 5269–5273. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.76.10.5269

Nei, M. (1987). Molecular evolutionary genetics. New York: Columbia University Press.

Pekas, A., & Wäckers, F. L. (2020). Bottom-up effects on tri-trophic interactions: Plant fertilization enhances the fitness of a primary parasitoid mediated by its herbivore host. Journal of Economic Entomology, 113, 2619–2626. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/toaa204

Pellmyr, O., & Leebens-Mack, J. (1999). Forty million years of mutualism: evidence for Eocene origin of the yucca-yucca moth association. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 96, 9178–9183. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.96.

16.9178

Pellmyr, O. (2003). Yuccas, yucca moths, and coevolution: a review. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden, 90, 35–55. https://doi.org/10.2307/3298524

Pigliucci, M. (2003). Phenotypic integration: studying the ecology and evolution of complex phenotypes. Ecology Letters, 6, 265–272. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1461-0248.2003.00428.x

Powell, J. A. (1989). Synchronized, mass-emergences of a yucca moth, Prodoxus Y-inversus (Lepidoptera: Prodoxidae), after 16 and 17 years in diapause. Oecologia, 81, 490–493. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00378957

Quicke, D. L. (2015). The Braconid and Ichneumonid parasitoid wasps: Biology, Systematics, Evolution and Ecology. Metopiinae. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell.

Resh, V. H., & Cardé, R. T. (Eds.). (2009). Encyclopedia of insects. San Diego, CA: Academic press.

Roderick, G. K. (1996). Geographic structure of insect populations: gene flow, phylogeography, and their uses. Annual Review of Entomology, 41, 325–352. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.en.41.010196.001545

Rogers, A. R., & Harpending, H. (1992). Population growth makes waves in the distribution of pairwise genetic differences. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 9, 552–569. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040727

Rozas, J., Sánchez-DelBarrio, J. C., Messeguer, X., & Rozas, R. (2003). DnaSP, DNA polymorphism analyses by the coalescent and other methods. Bioinformatics, 19, 2496–2497. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btg359

Sánchez, J. A., Romero, J., Ramírez, S., Anaya, S., & Carrillo, J. L. (1998). Géneros de Braconidae del estado de Guanajuato (Insecta: Hymenoptera). Acta Zoológica Mexicana (nueva serie), 79, 59–137. https://doi.org/10.21829/azm.1998.74741721

Sarfraz, M., Dosdall, L. M., & Keddie, B. A. (2009). Host plant nutritional quality affects the performance of the parasitoid Diadegma insulare. Biological Control, 51, 34–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2009.07.004

Schoonhoven, L. M., Van Loon, J. J., & Dicke, M. (2005). Insect-plant biology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Seifert, C. L., Strutzenberger, P., & Fiedler, K. (2022). Ecological specialisation and range size determine intraspecific body size variation in a speciose clade of insect herbivores. Oikos, 2022, e09338. https://doi.org/10.1111/oik.09338

Singer, M. S., & Stireman III, J. O. (2005). The tri-trophic niche concept and adaptive radiation of phytophagous insects. Ecology Letters, 8, 1247–1255. https://doi.org/10.

1111/j.1461-0248.2005.00835.x

Stillwell, R. C., & Fox, C. W. (2007). Environmental effects on sexual size dimorphism of a seed-feeding beetle. Oecologia, 153, 273–280. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-007-0724-0

Stillwell, R. C., & Fox, C. W. (2009). Geographic variation in body size, sexual size dimorphism and fitness components of a seed beetle: local adaptation versus phenotypic plasticity. Oikos, 118, 703–712. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0706.2008.17327.x

StiremanIII, J. O., Nason, J. D., & Heard, S. B. (2005). Host-associated genetic differentiation in phytophagous insects: general phenomenon or isolated exceptions? Evidence from a goldenrod-insect community. Evolution, 59, 2573–2587. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0014-3820.2005.tb00970.x

Takabayashi, J., & Dicke, M. (1996). Plant-carnivore mutualism through herbivore-induced carnivore attractants. Trends

in plant science, 1, 109–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1360-

1385(96)90004-7

Tamura, K., Dudley, J., Nei, M., & Kumar, S. (2007). MEGA4: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 24, 1596–1599. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msm092

Turner, R. M., Bowers, J. E., & Brugess, T. L. (2022). Sonoran Desert plants: an ecological atlas. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Vilhelmsen, L., Isidoro, N., Romani, R., Basibuyuk, H. H., & Quicke, D. L. (2001). Host location and oviposition in a basal group of parasitic wasps: the subgenual organ, ovipositor apparatus and associated structures in the Orussidae (Hymenoptera, Insecta). Zoomorphology, 121, 63–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004350100046

Visser, M. E. (1994). The importance of being large: the relationship between size and fitness in females of the parasitoid Aphaereta minuta (Hymenoptera: Braconidae). Journal of Animal Ecology, 63, 963–978. https://doi.org/10.

2307/5273

Wonglersak, R., Fenberg, P. B., Langdon, P. G., Brooks, S. J., & Price, B. W. (2020). Temperature-body size responses in insects: a case study of British Odonata. Ecological Entomology, 45, 795–805. https://doi.org/10.1111/een.12853