Pseudoregma panicola (Hemiptera: Aphididae), un registro nuevo sobre Arundo donax y su potencial como plaga urbana en México

Ana Lilia Muñoz-Viveros a, Damaris Arce-Lara a, Rebeca Peña-Martínez b, Alfonso David Ríos-Pérez c, Álvaro de Obeso-Fernández del Valle c, Juan Manuel Vanegas-Rico a, *

a Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Facultad de Estudios Superiores Iztacala, Unidad de Morfología y Función, Laboratorio de Control de Plagas, Av. de los Barrios No. 1, Los Reyes Iztacala, 54090 Tlalnepantla de Baz, Estado de México, Mexico

b Instituto Politécnico Nacional, Escuela Nacional de Ciencias Biológicas, Prolongación de Carpio y Plan de Ayala, Sto. Tomás, 11340 Ciudad de México, Mexico

c Tecnológico de Monterrey, Departamento de Bioingeniería, Escuela de Ingeniería y Ciencias, Av. Eugenio Garza Sada 2501, 64849 Monterrey, Nuevo León, Mexico

*Corresponding author: entomologo.mexicano@gmail.com (J.M. Vanegas-Rico)

Received: 30 April 2024; accepted: 28 February 2025

Abstract

Aphids are phytophagous insects that can affect the health of wild and urban vegetation, their effect being enhanced when they are exotic. The study was conducted in the garden of the Vasconcelos library, Mexico City. Insects were collected on ornamental Poaceae during December 2019, February 2020, and continued post-pandemic in 2023 (May-August 2023). Organisms were quantified and searched for natural enemies; morphological and molecular analyses of insects and plants were carried out. The aphid was determined as Pseudoregma panicola and Arundo donax as its host and first world report. Pseudoregma panicola and Arundo donax have molecular similarities with populations from Yunnan, China. The review of the scarce material from Mexico shows that P. panicola was collected from 1979 to 1981, on 3 wild species of Poaceae: ca. Phragmites in Morelos, Paspalum sp. and another undetermined species in Tamaulipas. The entomophagous present were: scarce larvae of Chamaemyiidae, and adults of the coccinellids Harmonia axyridis and Hippodamia convergens. The absence of parasitoids during 3 years of research, in addition to the low population of entomophagous, indicates an unfinished process of adaptation to this urban pest.

Keywords: Exotic insects; Poaceae; Chamaemyiidae

Resumen

Los áfidos son insectos fitófagos que pueden afectar la salud de la vegetación silvestre y urbana, cuyo efecto se potencia cuando son exóticos. El estudio se realizó en el jardín de la biblioteca Vasconcelos, Ciudad de México. Se recolectaron insectos sobre Poaceae ornamentales durante diciembre 2019, febrero 2020 y se continuó postpandemia en 2023 (mayo a agosto 2023). Se cuantificaron los organismos y se buscaron enemigos naturales; se realizaron análisis morfológicos y moleculares de los insectos y la planta. Se determinó el áfido como Pseudoregma panicola y Arundo donax como su hospedante, lo cual constituye el primer reporte mundial. Pseudoregma panicola y Arundo donax tienen cercanía molecular con poblaciones de Yunnan, China. La revisión del escaso material de colección en México muestra que P. panicola se recolectó de 1979 a 1981, sobre 3 especies silvestres de Poaceae:ca. Phragmites en Morelos, Paspalum sp. y otra especie sin determinar en Tamaulipas. Los entomófagos presentes fueron escasas larvas de Chamaemyiidae y adultos de los coccinélidos Harmonia axyridis e Hippodamia convergens. La ausencia de parasitoides durante 3 años de investigación, además de la baja población de entomófagos, indica un proceso inconcluso de adaptación de esta plaga urbana.

Palabras clave: Insectos exóticos; Poaceae; Chamaemyiidae

Introduction

Aphids are among the most significant pest groups affecting urban vegetation (Tello et al., 2005). They damage a wide range of host plants by sucking the juices from leaves and stems and producing honeydew. The damage is evident through symptoms such as discolored, battered, and yellowed leaves, as well as stunted growth, which detracts from the aesthetics of green areas and could represent a disease reservoir (Peña-Martínez, 1992; Rozo-Lopez et al., 2023; Tubby & Webber, 2010). Phytosanitary inspections are crucial in urban areas to ensure healthy vegetation, which, in turn, contributes to thermal comfort and indirectly reduces the risks of diseases (Tochaiwat et al., 2023; Yang et al., 2023).

In Mexico City, one of the largest cities in the world, commercial and tourist activities may facilitate the introduction of insect pests. The incursion of exotic aphids to Mexico can lead to severe economic impacts, like those generated by M. sorghi (also cited as M. sacchari) in sorghum crops during 2015 and 2016 (Peña-Martinez et al., 2016; Rodríguez-del Bosque & Terán, 2015). Therefore, it is essential to promptly document the presence of these exotic phytophagous insects and their hosts to mitigate potential damage to agricultural activities (Barczak et al., 2021; Korányi et al., 2021). Consequently, this study aims to report the presence of the aphid Pseudoregma panicola in ornamental plants in Mexico City.

Materials and methods

The sampling site was the garden of the Vasconcelos Public Library, located in Mexico City (19°26’53.5” N, 99°09’01.8” W; 2,241 m asl). This garden was created in 2006 to refurbish the city’s train station and incorporates 168 plant species from different sites (garden staff, personal communication).

The sample period spans from December 2019 to February 2020, when we observed and collected pest insects weekly. Following the COVID-19 pandemic, sampling was restarted in January 2023 to follow up on maintenance staff observations about the pest on Poaceae specimens used as ornamentals. The fieldwork at each visit consisted of 2 steps: photographing leaves (adaxial and abaxial side) with aphid colonies, including a metal ruler as a size reference, and sampling of these leaves, preserving them in airtight plastic bags for subsequent processing (rearing, mounting, and identifying natural enemies) in the Laboratorio de Control de Plagas de la Facultad de Estudios Superiores, Iztacala, UNAM. At the same time, another part of the plant material was provided to the herbarium of the same institution for identification.

The photographs were edited with Gimp software ver. 2.10.32 (The GIMP Development Team, 2023) to obtain tricolor images (green = leaf area, red = aphid specimens, white = background), including a centimeter scale. Then, images were processed with Image J software ver. 11 (Rasband, 2018) to estimate the area covered by the aphids on the adaxial and abaxial sides of the leaves. The abundance was calculated and compared with the M. sorghi infestation counting scale proposed for sorghum leaves (Bowling et al., 2015), using the original photos and Image J. Means and standard errors were calculated using SPSS software ver. 24.0 (IBM, 2016).

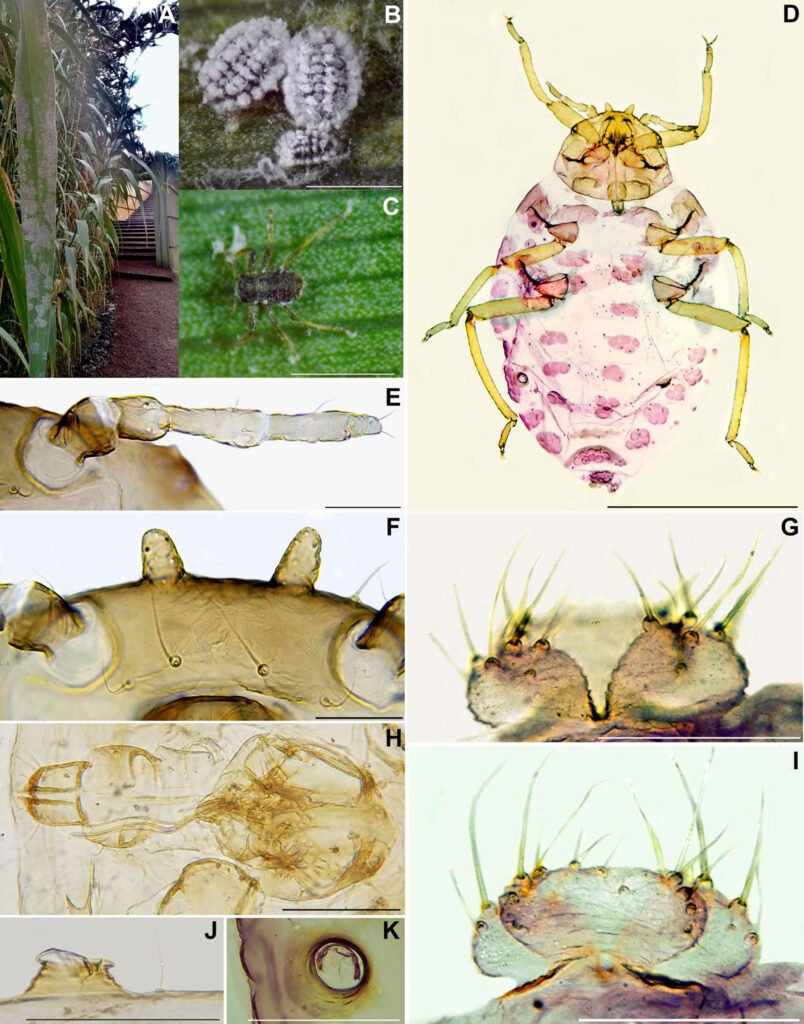

Some aphid specimens were processed according to the technique described by Blackman and Eastop (1994) and were identified according to the Noordam keys (1991). Part of the specimen material was preserved in 96% ethanol and kept refrigerated. Later, it was sent to the Laboratorio de Estrategias Ambientales y Fitotecnologías, of the Departmento de Bioingeniería at the Tecnológico de Monterrey for DNA extraction.

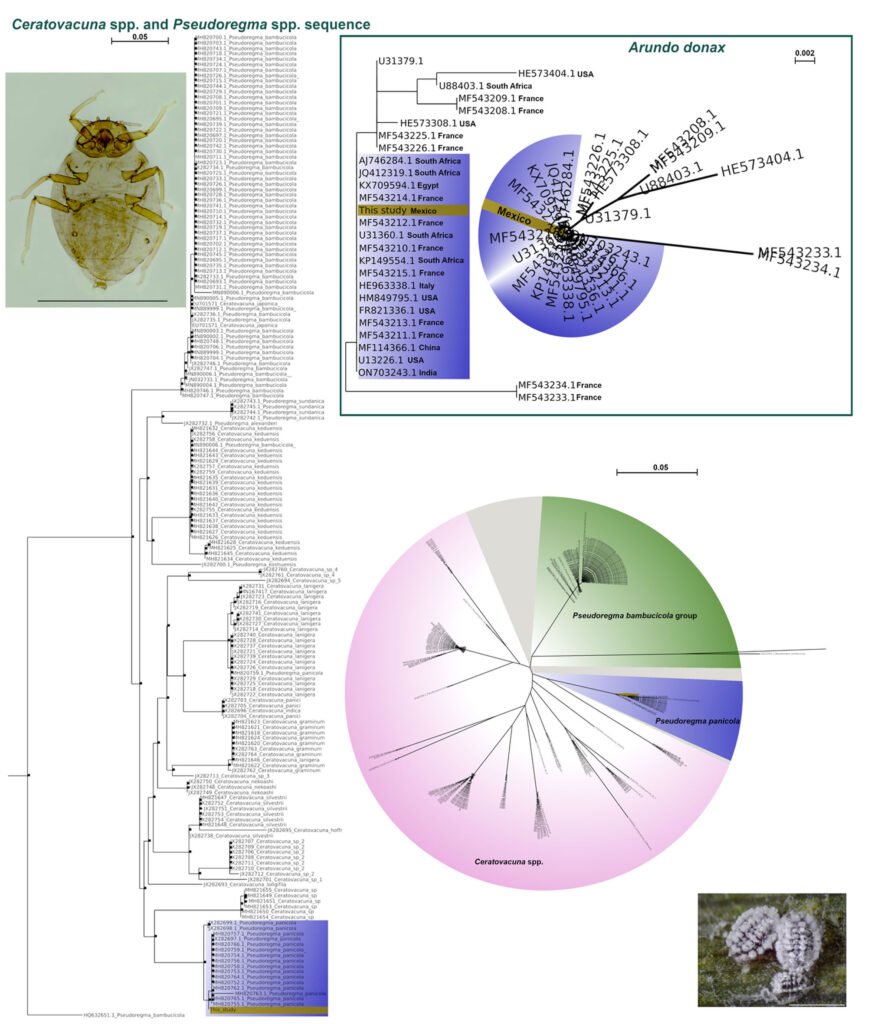

Molecular analyses were performed using cytochrome c oxidase I (COI) as suggested by several publications for aphids (Corsini et al., 1999; Folmer et al., 1994; Nováková et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2011). A PCR reaction to amplify a COI fragment was performed using the primers LCOI490 and HCO2198 (Folmer et al., 1994). The reaction was performed using a denaturing step of 95° for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles of 95° for 1 min, 45° for 1.5 min, and 72° for 1 min, and finishing with an extension of 3 min at 72°. The amplicon was purified using a QIAGEN PCR Purification Kit following the manufacturer’s instructions. Finally, the amplicon was sequenced using Sanger sequencing with the same primers, and the sequence was uploaded to NCBI with the accession number PQ196704. Once the sequence was obtained, a BLAST was performed to identify the organism (Altschul et al., 1990). Similar sequences were downloaded, cropped, and aligned (muscle algorithm) using MEGA XI when the organisms were identified. A phylogenetic tree was created using maximum likelihood (Tamura et al., 2021).

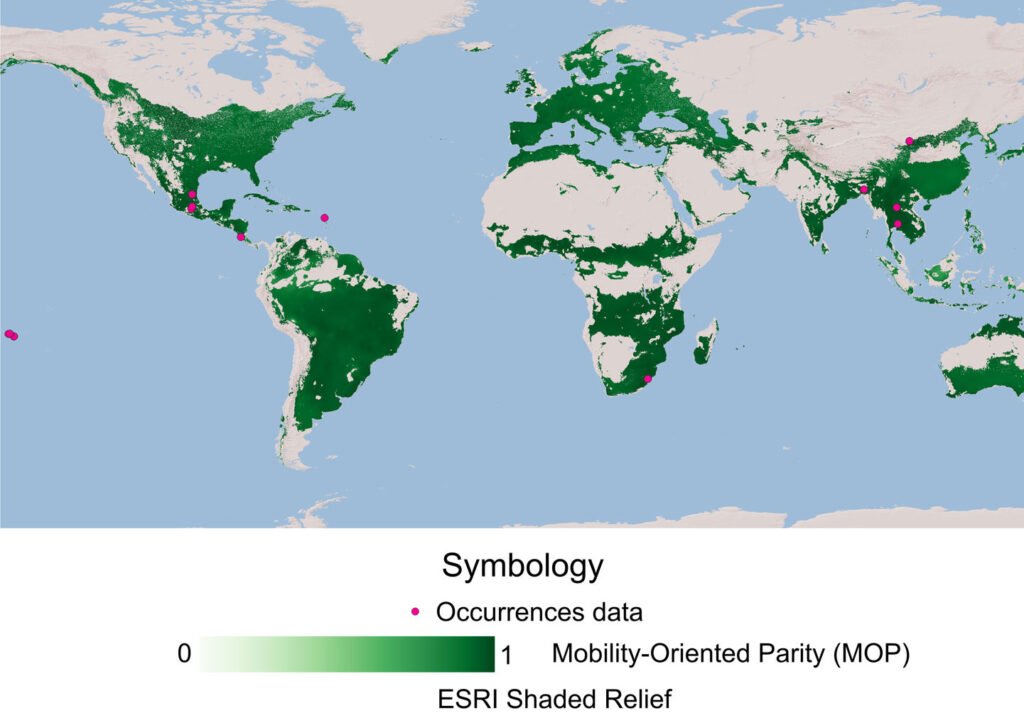

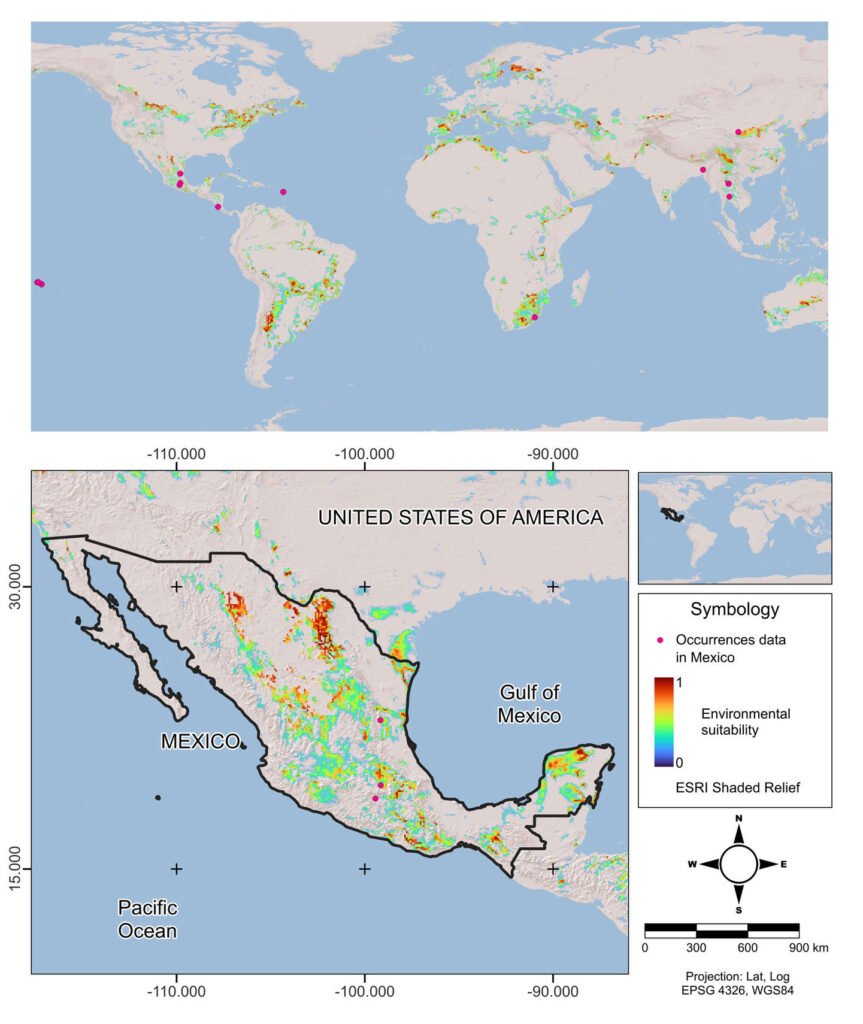

An ecological niche model was made with the field records in Mexico (by the authors) and from the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF.org, 2024) in Darwin Core format. The obtained data were subjected to 2 debugging processes: elimination of those records with coordinates 0 and 0, and elimination of duplicate data. Climatological variables were downloaded from WorldClim at a resolution of 5 arc minutes (≈ 10 km2) (Fick & Hijmans, 2017). The variables combining temperature and precipitation information, Bio8 – Mean temperature of the wettest quarter, Bio9 – Mean temperature of the driest quarter, Bio18 – Precipitation of the warmest quarter, and Bio19 – Precipitation of the coldest quarter, were removed due to the spatial anomalies they generate (Escobar et al., 2014).

The remaining 15 variables were used globally (except Antarctica) to avoid the risk of niche truncation (Chevalier et al., 2022). The variables were entered into the Niche A software (Qiao et al., 2016), and a principal component analysis (PCA) was performed. The 15 components were used to conduct ecological niche modeling based on the calibration zone and a 0.5-degree buffer (M, of the BAM model, Soberón et al., 2017). Using the ntbox package, more than 400 possible models were built within R, of which the one with the best omission and commission rates was kept (Osorio-Olvera et al., 2020). The resulting model was subjected to the MOP (Mobility-Oriented Parity) validation test, and only those regions that showed a low risk of extrapolation (near 1) were used (Owens et al., 2013).

Results

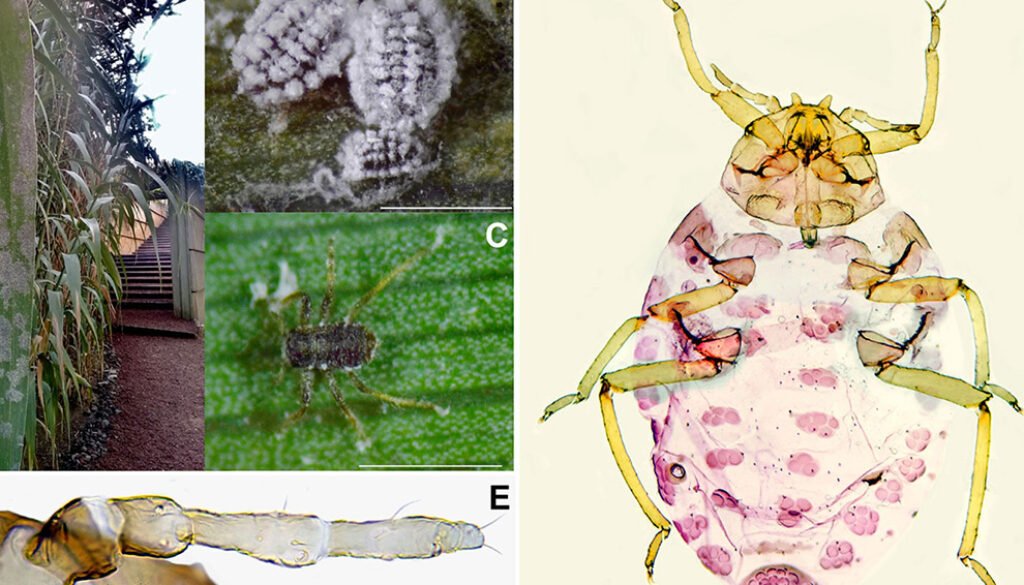

According to taxonomic identification and molecular test results, the specimens corresponded to Pseudoregma panicola (Takahashi) (Fig. 1). The host plant was determined by Izta Herbarium as Arundo donax L. The population density of P. panicola on this plant was estimated at 255 ± 65.4 individuals (range 75-750) per colony/leaf, with a more significant presence on the abaxial side, representing 46% of its cover. The leading group of associated entomophagous insects were silver fly larvae (Diptera: Chamaemyiidae), with an average abundance of 2.4 ± 0.8 (range 1-5) individuals/leaf over 3 years, besides a few adults of coccinellids (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae), Hippodamia convergens L., and Harmonia axyridis Pallas (0.12 ± 0.01 individuals per leaf/year). The population density of all predators was low compared to the pests. In the case of coccinellids, they were occasional, and immatures were not obtained.

Molecular sequence analysis indicated that the aphid P. panicola and its host A. donax, are most closely related to those sequenced from South Africa, Egypt, India, Italy, USA, and China (Fig. 2). Specimens of P. panicola from the latter country are most closely related to those sequenced from Poaceae in Yunnan Province, China, and, to a lesser extent, to specimens collected from Phyllostachys nigra Lodd. former Lindl. In the same region, the Fujian Province (Rui-Ling et al., 2013) (Fig. 3).

The model was only built with 60 occurrence points, of which 3 were obtained by the authors. The MOP achieved acceptable accuracy and a low risk of extrapolation values for Mexico, despite the fact that only 63 occurrence points were established (Fig. 4). For Mexico, regions such as the Yucatán Peninsula, the Valley of Mexico and northern and central Mexico seemed the most suitable to P. panicola distribution.

Discussion

The aphid P. panicola is reported in 4 continents: Africa —Argelia (Samia y Benoufella-Kitous, 2021), Asia —China (Holman, 2009; Riu-Ling, 2013), Japan (Holman, 2009), India (Holman, 2009; Singh & Singh 2018), Indonesia (Noordam, 1991), Nepal (Holman, 2009), and south of the Asian continent (Brumley, 2020), Oceania —Australia (Brumley, 2020) and New Zealand (Cottier, 1953), and America —Cuba, Costa Rica, Guadalupe, Puerto Rico, and Venezuela (Villalobos-Muller et al., 2010).

In Mexico, this species was initially reported by Peña-Martínez (1985), without specifying the host plant or location. Unedited documentary information from the Aphidomorpha collection of Mexico indicates that the aphid was collected by J. Butze at Coatlán del Río, Morelos, in 1979, on a host tentatively identified as Phragmites. The insects were identified by Dr. Remaudière in 1981, and the slide was subsequently donated to the former Dirección General de Sanidad Vegetal, today named Senasica. There are 2 unique slides in the Aphidomorpha collection: the first was surveyed from undetermined Poaceae on September 2nd, 1981, and the second on Paspalum sp. on September 4th, 1981; both collected by J. Holman and R. Peña-Martínez from Reserva de la Biosfera El Cielo, Gómez Farías, Tamaulipas, and corroborated in 2024 by the aphid specialists Ana Lilia Muñoz Viveros and Rebeca Peña Martínez.

Regarding P. panicola feeding, different genera of Poaceae were recorded as hosts: Andropogon, Arthraxon, Bambusa, Capillipedium, Cyrtococcum, Eragrostis, Ichnanthus, Indocalamus, Lasiacis, Oplismenus, Panicum, Paspalum, Phragmites, Phyllostachys, Pseudoechinolaena, Setaria, Stenthotheca, and Thysanolaena (Favret & Miller, 2012; Holman, 2009; Rui-Ling et al., 2013; Singh & Singh, 2018). Arundo donax is a new record of the host, which develops as secondary vegetation in the country, even as an ornamental, in various urban areas of Mexico City.

In Vasconcelos Library, A. donax occupies 80 m2 of the 2,600 m2 total garden area and is placed as a green barrier to hide the walls and give a feeling of thickness. The origin of purchase of this plant is uncertain; furthermore, no aphids or any other phytophagous have been recorded that have affected it since its placement (garden staff, personal communication). This green area is located near downtown Mexico City, where 3 public transportation systems converge, providing connections to the south, north, and east of the city, as well as to the airport, potentially facilitating the introduction of pest insects. Records on Phyllostachys nigra in Mexico indicate its presence in Nuevo León, Sinaloa, and San Luis Potosí (iNaturalist, 2024). Additionally, there are a few reports on the American continent (GBIF 2023), which also does not correspond to the continental distribution of P. panicola, suggesting that this plant is not the cause of its dispersal in America. A possible approach to discern the dispersal of P. panicola in Mexico would be the trade from Yunnan and other provinces of China to Central America and the USA, where Mexico is part of the naval route, and where plants with roots and foliage are sold for floral arrangements (Economic Complexity Observatory, 2023).

According to the Bowling’s scale infestation per leaf, the abundance of P. panicola on A. donax (up to 750 aphids) is higher than M. donacis (range 12 to 500 aphids) on the same host in Mexico (Vanegas-Rico et al., 2023), and M. sorghi on Sorghum (≈ 20-136 aphids) in Texas (Brewer et al., 2022). The low diversity of predators and the absence of parasitoids on P. panicola suggests that the potential natural regulators were in the process of adaptation during that period. Regarding exotic aphid populations, M. sorghi was detected in 2015, and more recently, M. donacis on A. donax in 2023. In the case of M. sorghi, at least 19 entomophagous (including 2 parasitoids) were recorded in northeastern Mexico sometime after its first report in the country (Rodríguez-del Bosque et al., 2018). The effect of natural enemies in Texas, 14 predators and 2 parasitoids, shows low abundance after 3-4 years of population studies (Brewer et al., 2022) compared to the initial report as a pest, where more than 1,000 aphids per leaf were observed (Bowling et al., 2015).

In the case of M. donacis, coccinellids and silver flies were observed preying on aphids during their first report in Mexico (Vanegas-Rico et al., 2023). Recently, laboratory observations indicated that ladybugs and silver flies could consume all instars of M. donacis; in fact, a low percent of parasitism (˂ 5%) was observed in the Valley of Mexico and Ensenada, Baja California (pers. com. Vanegas-Rico).

The identity of silver flies remains unknown due to limited material and inconclusive molecular results. This Diptera group can feed on different species of adelgids, aphids, soft scales, and other hemipterans (Gaimari et al., 2024; Salas-Monzón et al., 2020; Satar et al., 2015; Vanegas-Rico et al., 2010), exhibiting a density-dependence with their prey (Vanegas-Rico et al., 2017). The last bioecological aspect is relevant because it influences the success of biological control programs (Gaimari, 1991; Havill et al., 2018), and has favored the selection of some silver fly species as biological control agents in Europe (Justesen et al., 2023), USA (Ross et al., 2011; Havill et al., 2018), and Israel (Mendel et al., 2020).

According to site management personnel statements, P. panicola is controlled through broad-spectrum insecticide and sanitary pruning. This last method is frequently used when dry, greyish leaves and white spots (aphid wax) are observed. As a result, the aphid population densities recorded since 2023 are low (18.5 ± 4.2) and scarcer in coccinellids (2.6 ± 1.4) and silver flies (0.4 ± 0.1). So far, there was no evidence of parasitism in additional surveys of 2024. In the 2023 and 2024 samples, predation was observed on the aphid colonies and coccinellid eggs, mainly by H. axyridis andsporadic Syphid and Scymninae larvae. This suggests the continued adaptation process of these entomophagous and a possible adverse effect of pest management. Therefore, a biological control strategy for conservation must be implemented to promote the permanence of beneficial organisms and increase their populations.

Arundo donax has been encouraged as an ornamental plant so that the first negative impact would be in this type of urban system. There is still no prospecting in the agricultural landscape, despite the wide distribution of A. donax in 27 states of Mexico, mostly as a riparian system weed (Goolsby et al., 2023). The tendency of the A. donax distribution model (Goolsby et al., 2023) is similar to the current climate modeling of the aphid proposed in this work. This shows the potential for the establishment of the aphid in different states of the republic, highlighting its suitability in the Basin of Mexico and northern and southwestern parts of the country where this plant develops as an invader in bodies of water.

Finally, the work confirms the presence of P. panicola in Mexico and its development as an urban pest of A. donax, representing a New World host record for this aphid, and the first report from North America. Molecular information suggests China as a possible place of origin for both the plant and the aphid. Although this process is not entirely clear, it is feasible that the economic routes for transporting live or forage plants from this Asian country are a significant element to consider for the potential introduction of Poaceae phytophagous insects. The impact on this family of plants is currently unknown, so future studies should focus in that direction.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Francisco Amador-Cruz, Professor of Ecology career at FES-Iztacala, for elaborating the maps and for providing suggestions for this manuscript.

References

Altschul, S. F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E. W., & Lipman, D. J. (1990). Basic local alignment search tool. Journal of Molecular Biology, 215, 403–410. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2

Barczak, T., Bennewicz, J., Korczyński, M., Błażejewicz-Zawadzińska, M., & Piekarska-Boniecka, H. (2021). Aphid assemblages associated with urban park plant communities. Insects, 12, 173. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects12020173

Blackman, R. L., & Eastop, V. F. (1994). Aphid’s of the World’s trees. An identification and information guide. Wallingford, UK: CAB International.

Bowling, R., Brewer, M., Knutson, A., Way, M., Porter, P., Bynum, E. et al. (2015). Scouting sugarcane aphids. Retrieved December 18, 2023 from http://agrilife.org/mid-coast-ipm/files/2015/05/Scouting-Sugarcane-Aphids-2015.pdf

Brewer, M. J., Elliott, N. C., Esquivel, I. L., Jacobson, A. L., Faris, A. M., Szczepaniec, A. et al. (2022). Natural enemies, mediated by landscape and weather conditions, shape response of the sorghum agroecosystem of North America to the invasive aphid Melanaphis sorghi. Frontiers in Insect Science, 2, 830997. https://doi.org/10.3389/finsc.

2022.830997

Brumley, C. (2020). A checklist and host catalogue of the aphids (Hemiptera: Aphididae) held in the Australian National Insect Collection. Zootaxa, 4728, 575–600. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4728.4.12

Chevalier, M., Zarzo-Arias, A., Guélat, J., Mateo, R. G., & Guisan, A. (2022). Accounting for niche truncation to improve spatial and temporal predictions of species distributions. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 10, 944116. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2022.944116

Corsini, G., Manubens, A., Lladser, M., Lobos, S., Seelenfreund, D., & Lobos, C. (1999). AFLP analysis of the fruit fly Ceratitis capitata. Focus, 21, 72–73.

Cottier, W. (1953). Aphids of New Zealand. New Zealand Department of Scientific and Industrial Research Bulletin, 186, 1–382.

Economic Complexity Observatory. (2023). Retrieved December 14th, 2023 from: https://oec.world/es/profile/bilateral-country/chn/partner/usa?depthSelector=HS6Depth&dynamicBilateralTradeSelector=year2018&productSectionSelector=sectionID2#bi-trade-products

Escobar, L. E., Lira-Noriega, A., Medina-Vogel, G., & Peterson, A. T. (2014). Potential for spread of the white-nose fungus (Pseudogymnoascus destructans) in the Americas: use of Maxent and NicheA to assure strict model transference. Geospatial Health, 9, 221–229. https://doi.org/10.4081/gh.2014.19

Favret, C., & Miller, G. L. (2012). AphID. Identification Technology Program, CPHST, PPQ, APHIS, USDA; Fort Collins, CO. Retrieved on January 8, 2024 from: http://AphID.AphidNet.org/.

Fick, S. E., & Hijmans, R. J. (2017). WorldClim 2: new 1km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. International Journal of Climatology, 37, 4302–4315. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.5086

Folmer, O., Black, M., Hoeh, W., Lutz, R., & Vrijenhoek, R. (1994). DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Molecular Marine Biology and Biotechnology, 3, 294–299.

Gaimari, S. D. (1991). Use of silver flies (Diptera: Chamaemyiidae) for biological control of homopterous pests. Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington, 53, 947–950.

Gaimari, S. D., González, C. R., & Elgueta, M. (2024). A catalog of the Chamaemyiidae of Chile (Diptera: Lauxanioidea). Zootaxa, 5399, 555–569. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.5399.5.5

Goolsby, J. A., Moran, P. J., Martínez-Jiménez, M., Yang, C., Canavan, K., Paynter, Q. et al. (2023). Biology of Invasive Plants 4. Arundo donax L. Invasive Plant Science and Management, 16, 81–109. https://doi.org/10.1017/inp.2023.17

GBIF (Global Biodiversity Information Facility). (2023). Phyllostachys nigra. Retrieved September 14th, 2023. From: https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.y5xrtv

GBIF (Global Biodiversity Information Facility). (2024). Pseudoregma panicola. Retrieved August 20th, 2024. From https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.6n5574

Havill, N. P., Gaimari, S. D., & Caccone, A. (2018). Cryptic east-west divergence and molecular diagnostics for two species of silver flies (Diptera: Chamaemyiidae: Leucopis) from North America being evaluated for biological control of hemlock woolly adelgid. Biological Control, 121, 23–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2018.02.004

Holman, J. (2009). Host plant catalog of aphids: Paleartic Region. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-8286-3

IBM Corp. (2016). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 24.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

iNaturalist community. (2024). Observaciones de Phyllostachys nigra de México. Retrieved on January 12, 2024. From: https://mexico.inaturalist.org/taxa/166766-Phyllostachys-nigra

Justesen, M. J., Seehausen, M. L., Havill, N. P., Kenis, M., Gaimari, S. D., Matchutadze, I. et al. (2023). Evaluation of Leucopis hennigrata (Diptera: Chamaemyiidae) as a classical biological control agent of Adelges nordmannianae (Hemiptera: Adelgidae) in northern Europe. Biological Control, 183, 105264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.

2023.105264

Korányi, D., Szigeti, V., Mezőfi, L., Kondorosy, E., & Markó, V. (2021). Urbanization alters the abundance and composition of predator communities and leads to aphid outbreaks on urban trees. Urban Ecosystems, 24, 571–586. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-020-01061-8

Mendel, Z., Protasov, A., Vanegas-Rico, J. M., Lomeli-Flores, J. R., Suma, P., & Rodríguez-Leyva, E. (2020). Classical and fortuitous biological control of the prickly pear cochineal, Dactylopius opuntiae, in Israel. Biological Control, 142, 104157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2019.104157

Noordam, D. (1991). Hormaphidinae from Java (Homoptera: Aphididae). The Zoologische Verhandelingen, 270, 1–525.

Nováková, E., Hypša, V., Klein, J., Foottit, R. G., von Dohlen, C. D., & Moran, N. A. (2013). Reconstructing the phylogeny of aphids (Hemiptera: Aphididae) using DNA of the obligate symbiont Buchnera aphidicola. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 68, 42–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2013.03.016

Osorio-Olvera, L., Lira-Noriega, A., Soberón, J., Peterson, A. T., Falconi, M., Contreras-Díaz, R. G. et al. (2020). ntbox: an R package with graphical user interface for modeling and evaluating multidimensional ecological niches. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 11, 1199–1206. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210x.13452

Owens, H. L., Campbell, L. P., Dornak, L. L., Saupe, E. E., Barve, N., Soberón, J. et al. (2013). Constraints on interpretation of ecological niche models by limited environmental ranges on calibration areas. Ecological Modelling, 263, 10–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2013.04.011

Qiao, H., Peterson, A. T., Campbell, L. P., Soberón, J., Ji, L., & Escobar, L. E. (2016). NicheA: creating virtual species and ecological niches in multivariate environmental scenarios. Ecography, 39, 805–813. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.01961

Peña-Martínez, R. (1985). Ecological notes on aphids of the high plateau of Mexico with a check-list of species collected in 1980. In Proceedings of the International Aphidological Symposium (pp. 425–430). Jablonna. Polska Akademia Nauk, Warsaw.

Peña-Martínez, R. (1992). Biología de áfidos y su relación con la transmisión de virus. In C. Urias, R. Rodríguez, & T. Alejandre (Eds). Áfidos como vectores de virus en México: contribución a la ecología y control de áfidos en México (pp. 11–35). CEFIT-CP. Vol 1. Montecillo, Estado de México, México.

Peña-Martínez, R., Muñoz-Viveros, A. L., Bujanos-Muniz, R., Luevano-Borroel, J., Tamayo-Mejía, F., & Cortez-Mondaca, E. (2016). Sexual forms of sorghum aphid complex

Melanaphis sacchari/sorghi in Mexico. Southwestern

Entomologist, 41, 127–132. https://doi.org/10.3958/059.041.0114

Rasband, W. S. (2018). Software ImageJ, U. S. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA. https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/

Rodríguez-del Bosque, L. A., & Terán, A. P. (2015). Melanaphis sacchari (Hemiptera: Aphididae): a new sorghum insect pest in Mexico. Southwestern Entomologist, 40, 433–434. https://doi.org/10.3958/059.040.0217

Rodríguez-del Bosque, L. A., Rodríguez-Vélez, B., Sarmiento-Cordero, M. A., & Arredondo-Bernal, H. C. (2018). Natural enemies of Melanaphis sacchari on Grain Sorghum in Northeastern Mexico. Southwestern Entomologist, 43, 277–279. https://doi.org/10.3958/059.043.0103

Ross, D. W., Gaimari, S. D., Kohler, G. R., Wallin, K. F., & Grubin, S. M. (2011). Chamaemyiid predators of the hemlock woolly adelgid from the Pacific Northwest. In Brad Onken, R. O., & R. Reardon (Eds.), Implementation and status of biological control of the hemlock woolly adelgid (pp. 97–106). USDA Forest Service.

Rozo-Lopez, P., Brewer, W., Käfer, S., Martin, M. M., & Parker B. J. (2023). Untangling an insect’s virome from its endogenous viral elements. BMC Genomics, 24, 636. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-023-09737-z

Rui-Ling, Z., Xiao-Lei, H., Li-Yun, J., & Ge-Xia, Q. (2013). Molecular phylogenetic evidence for paraphyly of Ceratovacuna and Pseudoregma (Hemiptera, Hormaphidinae) reveals late Tertiary radiation. Bulletin of Entomological Research, 103, 644–655. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007485313000321

Salas-Monzón, R., Rodríguez-Leyva, E., Lomeli-Flores, J. R., & Vanegas-Rico, J. M. (2020). How two predators feed on Dactylopius opuntiae beneath its ventral side. Southwestern Entomologist,45, 823–826. https://doi.org/10.3958/059.045.0324

Samia, A. I. T., & Benoufella-Kitous, K. (2021). Diversity of aphids (Hemiptera: Aphididae) associated with potato crop in Tizi-Ouzou (North of Algeria), with new records. Acta Agriculturae Slovenica, 117, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.14720/aas.2021.117.1.1768

Satar, S., Raspi, A., Özdemir, I., Tusun, A., Karacaoğlu, M., & Benelli, G. (2015). Seasonal habits of predation and prey range in aphidophagous silver flies (Diptera, Chamaemyiidae), an overlooked family of biological control agents. Bulletin of Insectology, 68, 173–180.

Singh, G., & Singh, R. (2018). Updated checklist of Indian Hormaphidinae (Aphididae: Hemiptera) and their food plants. Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies, 6, 1345–1352.

Soberón, J., Osorio-Olvera, L., & Peterson, T. (2017). Diferencias conceptuales entre modelación de nichos y modelación de áreas de distribución. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 88, 437–441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmb.2017.03.011

Tamura, K., Stecher, G., & Kumar, S. (2021). MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis V.11. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 38, 3022–3027. https://doi.org/10.

1093/molbev/msab120

Tello, M. L., Tomalak, M., Siwecki, R., Gáper, J., Motta, E., & Mateo-Sagasta, E. (2005). Biotic urban growing conditions-threats, pests and diseases. In C. Konijnendijk, K. Nilsson, T. Randrup, & J. Schipperijn (Eds.), Urban forests and trees: a reference book (pp. 325–365). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.

1007/3-540-27684-X_13

The GIMP Development Team. (2023). GNU Image Manipulation Program (GIMP), Version 2.10.32. Community, Free Soft-

ware. https://www.gimp.org/

Tochaiwat, K., Phichetkunbodee, N., Suppakittpaisarn, P., Rinchumphu, D., Tepweerakun, S., Kridakorn Na Ayutthaya, T.et al. (2023). Eco-efficiency of green infrastructure on thermal comfort of outdoor space design. Sustainability, 15, 2566. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032566

Tubby, K. V., & Webber, J. F. (2010). Pests and diseases threatening urban trees under a changing climate. Forestry: An International Journal of Forest Research, 83, 451–

459. https://doi.org/10.1093/forestry/cpq027

Vanegas-Rico, J. M., Lomeli-Flores, J. R., Rodríguez-Leyva, E., Mora-Aguilera, G., & Valdez, J. M. (2010). Enemigos naturales de Dactylopius opuntiae (Cockerell) en Opuntia ficus-indica (L.) Miller en el centro de México. Acta Zoológica Mexicana, 26, 415–433. https://doi.org/10.21829/azm.2010.262718

Vanegas-Rico, J. M., Pérez-Panduro, A., Lomeli-Flores, J. R., Rodríguez-Leyva, E., Valdez-Carrasco, J. M., & Mora-Aguilera, G. (2017). Dactylopius opuntiae (Cockerell) (Hemiptera: Dactylopiidae) population fluctuations and predators in Tlalnepantla, Morelos, México. Folia Entomológica Mexicana (nueva serie), 3, 23–31.

Vanegas-Rico, J. M., Peña-Martínez, R., & Muñoz-Viveros, A. L. (2023). First record of Melanaphis donacis (Passerini, 1861) (Hemiptera: Aphididae) in México. Entomological Communications, 5, ec05031. https://doi.org/10.37486/2675-1305.ec05031

Villalobos-Muller, W., Pérez-Hidalgo, N., Mier-Durante, P., & Nieto-Nafría, J. M. (2010). Aphididae (Hemiptera: Sternorrhyncha) from Costa Rica, with new records for Central America. Boletín de la Asociación Española de Entomología, 34, 145–182.

Yang, T., Gu, T., Xu, Z., He, T., Li, G., & Huang, J. (2023). Associations of residential green space with incident type 2 diabetes and the role of air pollution: a prospective analysis in UK Biobank. Science of the Total Environment, 866, 161396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.161396

Zhang, R., Huang, X., Jiang, L., & Qiao, G. (2011). Phylogeny and species differentiation of Mollitrichosiphum spp. (Aphididae, Greenideinae) based on mitochondrial COI and Cyt b genes. Current Zoology, 57, 806–815. https://doi.org/10.1093/czoolo/57.6.806