Ontogenetic allometry and non-size-dependent variation of head shape in the Mexican Dusky Rattlesnake

Aldo Gómez-Benitez a, b, *, Erika Adriana Reyes-Velázquez b, c, Justin Rheubert d, Oswaldo Hernández-Gallegos c

a Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, Unidad Lerma, División de Ciencias Biológicas y de la Salud, Departamento de Ciencias Ambientales, Av. de las Garzas No. 10, El Panteón, 52005 Lerma, Estado de México, Mexico

b Red de Investigación y Divulgación de Anfibios y Reptiles MX, Guadalupe Victoria No. 33, 56800 Ozumba de Alzate, Estado de México, México

c Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México, Facultad de Ciencias, Laboratorio de Herpetología, Instituto Literario No. 100, Colonia Centro, 50000 Toluca, Estado de México, Mexico

d University of Findlay, Department of Biology, 1000 N. Main St., Findlay, Ohio, 45840 USA

*Corresponding author: gobeal940814@gmail.com (A. Gómez-Benitez)

Abstract

The evolutionary role of ontogenetic allometry is a topic of debate, as it can act as an evolutionary constraint or as a mechanism for functional optimization. We assessed the allometric changes in head shape of Crotalus triseriatus (Wagler, 1830) to understand how ontogenetic shifts in head morphology adapts to ecological demands as it grows. The sampling was conducted in Toluca de Lerdo, Estado de México, where dorsal-view photographs of the head were taken for the 22 collected specimens. We digitized 22 landmarks that represent the C. triseriatus head shape. We calculated the common allometric component and the residual shape components (RSC). Results showed statistically significant positive allometry, considering shape as a function of size, in the head shape of C. triseriatus. The main changes include a contraction along the sagittal plane, primarily in the snout region, and a marked expansion in the posterior part of the head. Size being the main source of variation appears to be a common pattern in snakes, though the functional source of the variation may relate to the natural history aspects of each species. In C. triseriatus, these changes seem to be associated with predatory efficiency.

Keywords: Crotalus triseriatus; Common allometric component; Geometric morphometrics; Natural history; Predatory efficiency; RSC

Alometría ontogenética y variación no dependiente del tamaño en la forma de la cabeza de la Serpiente de Cascabel Transvolcánica

Resumen

El papel evolutivo de la alometría ontogenética es un tema debatido, pues puede actuar como una restricción evolutiva o como un mecanismo de optimización funcional. Evaluamos los cambios alométricos en la forma de la cabeza de Crotalus triseriatus (Wagler, 1830) para entender cómo los cambios ontogenéticos se ajustan a las demandas ecológicas a lo largo del crecimiento. El muestreo se llevó a cabo en Toluca de Lerdo, Estado de México, se tomaron fotografías dorsales de la cabeza de los 22 especímenes recolectados. Digitalizamos 22 puntos de referencia que representan la forma de la cabeza de C. triseriatus. Calculamos el componente alométrico común y los componentes residuales de la forma (CRF). Los resultados mostraron una alometría positiva estadísticamente significativa, considerando la forma como función del tamaño, en la cabeza de C. triseriatus. Los principales cambios incluyen una contracción a lo largo del plano sagital, en la región del hocico y una expansión marcada en la parte posterior de la cabeza. La talla como principal fuente de variación es un patrón común en serpientes, aunque su origen funcional puede depender de la historia natural de cada especie. En C. triseriatus, estos cambios están relacionados con la eficiencia depredadora.

Palabras clave: Crotalus triseriatus; Componente alométrico común; Morfometría geométrica; Historia natural; Eficiencia depredadora; CRF

Introduction

Allometry refers to the study of size and its biological consequences in morphology and function, typically focusing on how the proportions of body structures relate to each other at specific determined time or throughout development (Gould, 1966; Pretzsch, 2009). Modern studies of allometry are based on Huxley’s (1932) research, where he introduced the allometric equation, the concept of relative growth —different body parts grow at different rates— and hypothesized its evolutionary significance. Allometry is classified into 3 types: 1) static allometry which describes the relationship between body parts within a population at a given developmental stage, 2) evolutionary allometry which examines these relationships across populations or species, and 3) ontogenetic allometry which investigates changes in body proportions during growth, providing key insights into developmental processes (Pélabon et al., 2014). The evolutionary significance of allometry is debated, as it can act both as an evolutionary constraint, by which differential growth relationships restrict the range of phenotypic variation available for selection, and as a mechanism for functional optimization (Le Verger et al., 2023; Voje et al., 2022). While the allometric relationships observed during organisms’ development can act as evolutionary constraints, guiding species along fixed developmental trajectories (Voje et al., 2022), these same relationships are also shaped by natural selection to optimize functional traits, highlighting an adaptive dimension of allometry (Le Verger et al., 2023; Strelin & Diggle, 2022).

In reptiles, allometric patterns vary widely. In the fossorial species Cynisca leucura (Amphisbaenia), allometry acts as an evolutionary constraint, limiting cranial morphology to maintain proportions suitable for head-first digging (Hipsley et al., 2016). Sexual selection also influences allometry, as seen in Anolis species, where divergent dewlap growth trajectories are linked to reproductive pressures, though all exhibit positive allometry (Stroud et al., 2023). Similarly, in snakes of the genus Malacophagus, sexual dimorphism is reflected in distinct allometric trajectories between males and females (Dos Santos et al., 2022). In crocodilians, dietary demands drive allometry, enabling the consumption of larger prey as the animal grows (Balaguera-Reina et al., 2024; Dodson, 1975). These examples demonstrate that reptile allometry exhibits diverse patterns, making this group ideal for studying allometry. A robust method to assess the relationship between shape and size is the calculation of the Common Allometric Component (CAC), as described by Mitteroecker et al. (2004). The CAC captures allometric variation by summarizing how shape changes as a function of size across all specimens. This metric has been previously applied in reptile studies to evaluate evolutionary shifts in squamate cranial morphology during development and its relationship with whole-head integration (Hipsley & Müller, 2017; Ollonen et al., 2024), proving to be an excellent tool for studying allometry.

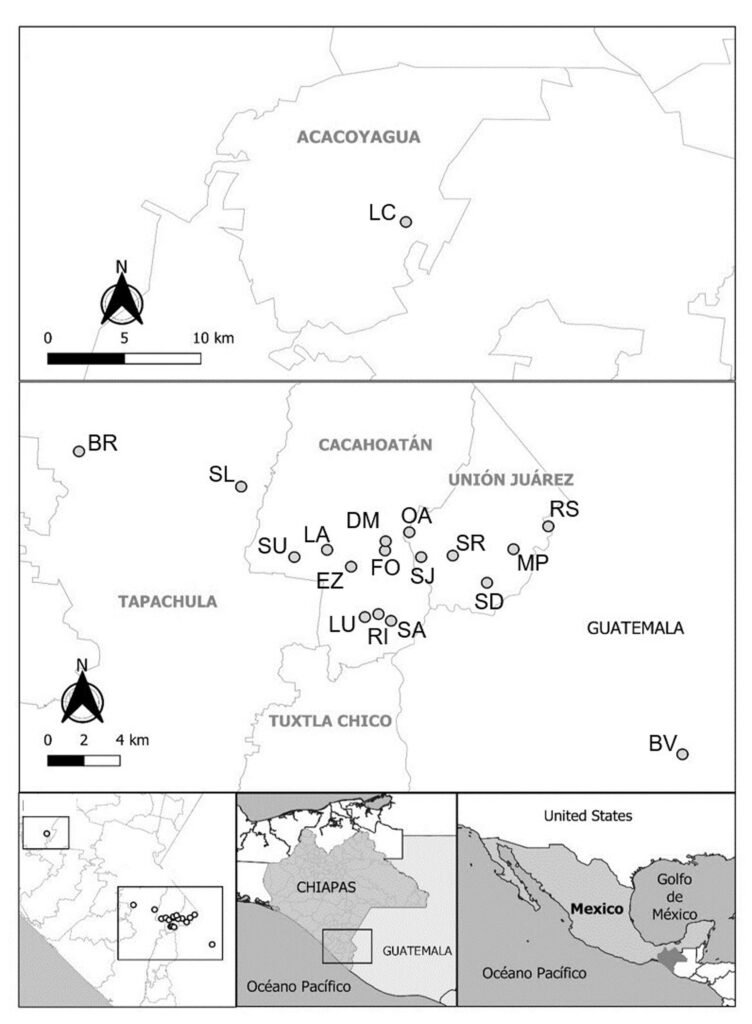

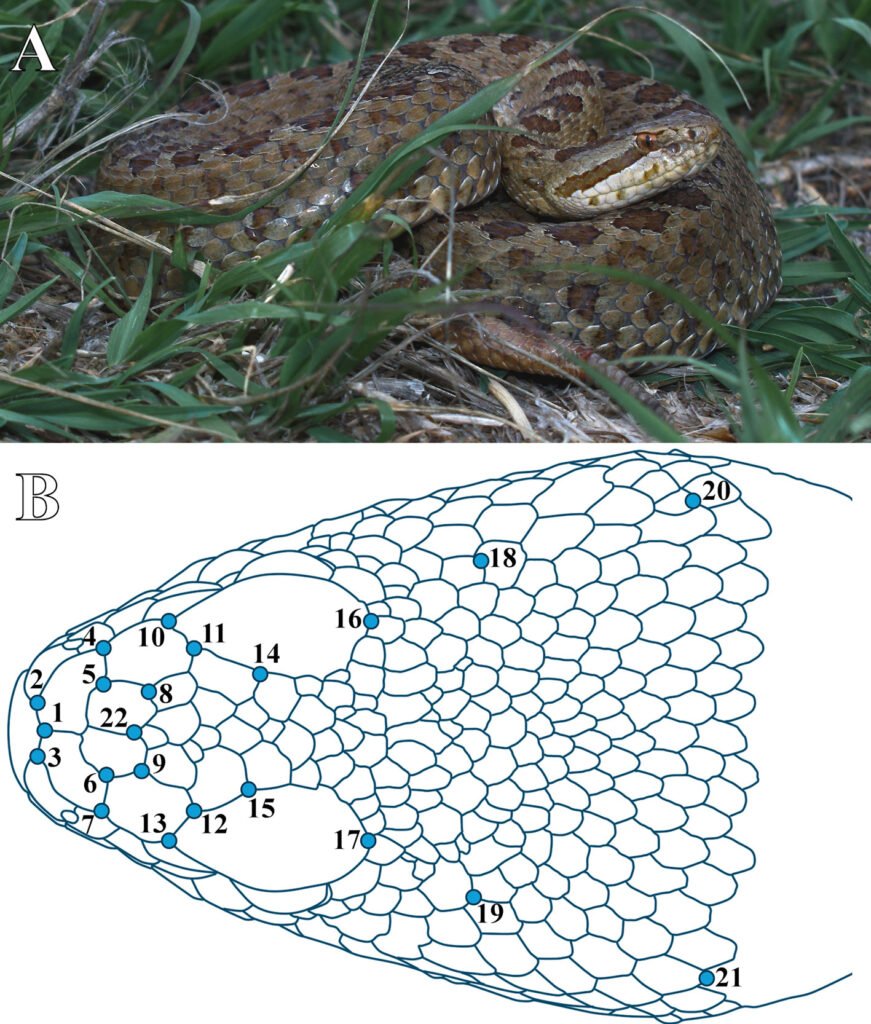

We selected the Mexican Dusky Rattlesnake (Crotalus triseriatus) as a study model because, as a fully terrestrial predator with clearly defined foraging and dietary habits, it offers a well‑characterized system to link ontogenetic shape changes with ecological and biotic interactions. Crotalus triseriatus (Wagler, 1830), is a medium-sized venomous snake endemic to Mexico (Fig. 1A), found in the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt across the states of Veracruz, Puebla, Tlaxcala, Morelos, Estado de México, and Michoacán, at elevations between 1,905 and 4,572 m asl (Campbell & Lamar, 2004; Castillo-Juárez et al., 2021). Their primary habitat is coniferous forests and oak forest (primarily pine-oak forests), grasslands, montane cloud forests, and agroecosystems (Campbell & Lamar, 2004; Castillo-Juárez et al., 2021; Gómez-Benitez, 2023). This species is diurnal to crepuscular, preying on lizards, rodents, and salamanders; additionally, C. triseriatus exhibits a distinct ontogenetic dietary shift, transitioning from ectothermic prey to mammals as the snakes grow (Mociño-Deloya et al., 2014; Ramírez-Bautista et al., 2009).

Figure 1. A, Mexican Dusky Rattlesnake at the study site in Cerrillo Piedras Blancas, Toluca de Lerdo, Estado de México, Mexico; B, location of the 22 landmarks digitized.

In the present study, we analyzed the allometric changes in head shape of C. triseriatus using geometric morphometrics, a set of multivariate statistical methods that quantify organismal shape by analyzing the Cartesian coordinates of homologous anatomical landmarks, to characterize the ontogenetic variation in head morphology of a species known for exhibiting ontogenetic shifts in its ecological interactions. Understanding these morphological changes provides valuable insights into how this species adapts to ecological demands as it grows and contributes to a greater understanding of allometry in an evolutionary sense.

Materials and methods

We conducted fieldwork in an agroecosystem located in El Cerrillo, Piedras Blancas, within the municipality of Toluca de Lerdo, Estado de México, Mexico. The study area is characterized by an arboreal stratum primarily composed of Salix babilonica, Cupressus sp. and Casuarina equisetifolia, the herbaceous stratum contains over 118 species of angiosperms (Álvarez-Lopeztello et al., 2016). The study site is disturbed due to agricultural practices (many of them unregulated), livestock, constant human presence and intentional killing of snakes. We searched for rattlesnakes in various microhabitats, including under rocks, inside and alongside a cement irrigation canal, and under polypropylene plastic sheets previously used as waterproofing membranes in agricultural activities at the site. Field researchers wore protective snake gaiters and bait gloves, and rattlesnakes were handled using herpetological hooks. The research team has a detailed snakebite emergency protocol, which includes always carrying sufficient vials of antivenom to ensure support dose administration if required. We took dorsal photographs of the collected individuals heads using a Nikon D3500 camera (settings: 1/200 shutter speed, f/22 aperture, ISO 100-400) equipped with a Nikkor 70-300 mm lens at its maximum focal length. To avoid the limitation of the lens minimum focusing distance, we used macro extension tubes. The camera was mounted on a tripod and positioned 60 cm above the specimens. Additionally, the photographs were illuminated using the camera built-in flash to ensure consistent lighting. Only one dorsal photograph of the head was taken per individual for geometric morphometric analysis. Snakes were handled following standard safety protocols: individuals were manipulated using herpetological hooks and gently positioned over a millimetric sheet, ensuring that the head lay flat and straight. When necessary, restraining tubes were used to guide the head into position. All photographs were taken in the field; specimens were not transported to the laboratory. Instead, to guarantee photograph quality, individuals were briefly placed in cloth bags and moved to a flat surface present at the study site. All individuals were sexed through hemipenes eversion, measured in SVL and released where they were captured.

Using TPSDig 2.31, we digitized 22 anatomical landmarks on the dorsal view of the head of C. triseriatus (Fig. 1B, Table 1), in duplicate. Landmarks were placed at intersections of external cranial scales to avoid invasive procedures, as all specimens were alive. These points were selected based on their anatomical relevance and their ability to capture overall head shape, with particular emphasis on regions of functional and evolutionary interest such as the snout, the orbital area, and the venom delivery system. In addition, the chosen landmarks enable the analysis of head proportions, including width and length. Because our aim was to study ontogenetic allometry, individuals were analyzed jointly regardless of age class, in order to capture variation in shape throughout development. A Procrustes superimposition was then performed in MorphoJ (Klingenberg, 2011) to remove differences in size, position, and orientation according with the methodology proposed by Dryden and Mardia (1998). The data were projected onto the tangent space of the shape space, enabling linear analysis of shape variation (Dryden & Mardia, 1998). This method retains centroid size information for subsequent analyses, such as allometry studies.

Table 1

Position of the 22 landmarks selected to represent the head shape of Crotalus triseriatus (see Fig. 1B).

| Landmarks | Description |

| 1 | Between the internasal scales, posterior to rostral |

| 2, 3 | Intersection between the first nasal and internasal scales |

| 4, 7 | Intersection between the second nasal, intercanthal and prefrontal scales |

| 5, 6 | Intersection between internasal, intercanthal and prefrontal scales |

| 8, 9 | Intersection between intercanthal, prefrontal and the first row of frontal scales |

| 10, 13 | Distal intersection between prefrontal and supraocular scales |

| 11, 12 | Intersection between prefrontal, supraocular and second row of frontal scales |

| 14, 15 | Anterior intersection of supraocular and intersupraocular scales |

| 16, 17 | Intersection between the supraocular scales and the first row of the scales in the crown of the head |

| 18, 19 | Posterior part of the most distal fourth row of the scales in the crown of the head |

| 20, 21 | Posterior part of the most distal eighth row of the scales in the crown of the head |

| 22 | Intersection between both intercanthal and first row of frontal scales |

After Procrustes superimposition, we conducted a multiple linear regression in MorphoJ with the Cartesian coordinates of the 22 landmarks (44 dependent variables: X and Y for each landmark) as the response and the log‑transformed centroid size as the predictor. This approach allowed us to quantify how head shape (landmark coordinates) changes in relation to overall head size (log‑transformed centroid size). To assess the statistical power of our regression analysis, we conducted a power analysis using the pwr package (Champely, 2020) in R (R Core Team, 2021). Results were considered significative at an α = 0.05.

To assess the changes related to size in C. triseriatus, and the non-size-dependent variation, we employed the CAC and the residual shape components (RSC). The CAC was calculated conducting a linear regression of shape as a function of size (Mitteroecker et al., 2004). The RSC represents the variation in shape that is not attributable to size. The residuals obtained during the linear regression were analyzed using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to extract RSC (Mitteroecker et al., 2004). To correctly display the changes detected with the CAC and RSC, we calculated the Jacobian expansion factor using PAST4 version 4.17 (Hammer et al., 2001). This calculation involves deriving a Jacobian matrix from a thin-plate spline deformation (or warp), which quantifies local shape changes by relating the derivatives of the deformed configuration to a consensus configuration, or from smaller to bigger individuals in the case of CAC. The expansion factor, determined as the determinant of the Jacobian matrix, reflects the local area distortion resulting from the deformation, providing insight into the degree of expansion or contraction across regions of the shape.

Finally, we plotted the CAC against log-transformed centroid size and against the RSC. We also calculated the standard deviation to understand the patterns of variation related to allometry and non-size-dependent factors. These exploratory analyses allow us to visualize the relationships between size and shape variations, and how non-allometric factors contribute to morphological changes in C. triseriatus.

Results

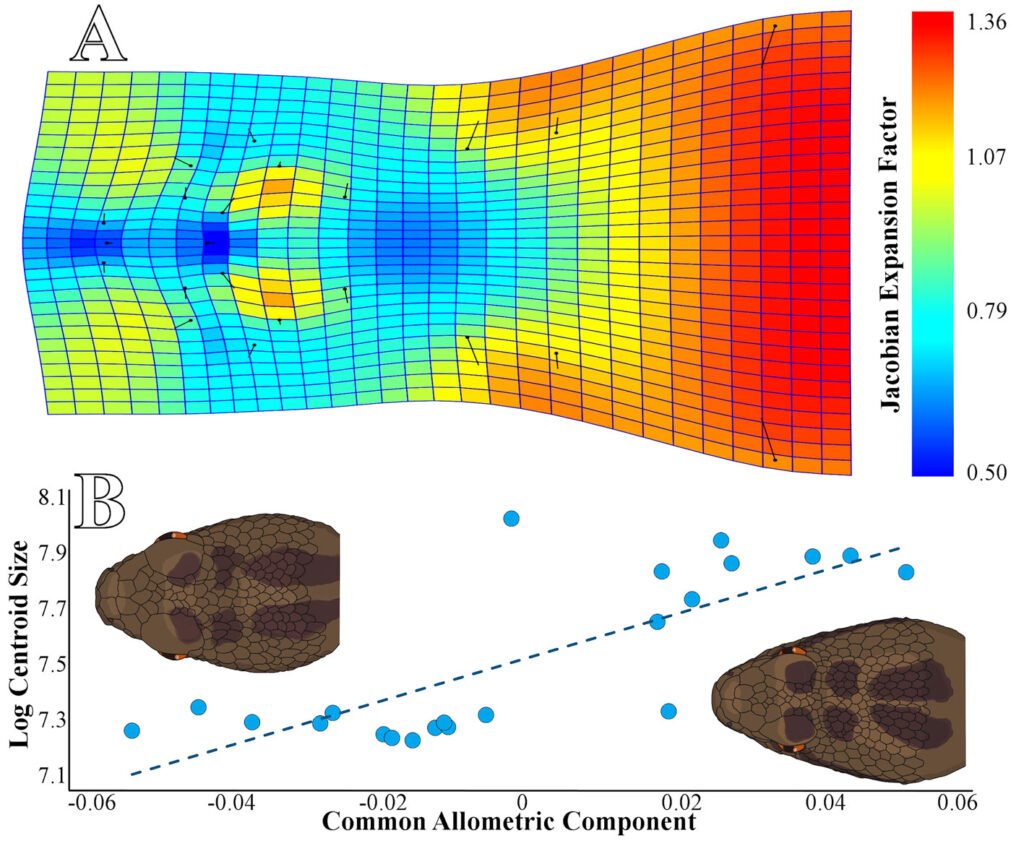

We collected a total of 22 individuals, including 13 juveniles and 9 adults, based on SVL, including 7 females and 15 males. The multiple linear regression results show a significant relationship between head shape and log centroid size (R2 = 0.4992, p = 0.0122), indicating a positive allometry (Fig. 2A). Our statistical power analysis revealed that the regression model had a power of 0.993, indicating a high resolution of our model with a 99.3% probability of detecting a significant relationship between head shape and log centroid size in C. triseriatus. In other words, there is a very low probability (0.7%) of committing a Type II error (Whitlock & Schluter, 2008).

The CAC analysis (Fig. 2A) revealed the following changes in the head shape of C. triseriatus: a contraction between the internasal scales and the rostral, resulting in a more square-shaped snout in adults than in juveniles (landmarks 1-3); a contraction of the prefrontal scales over the intercanthals, reducing the proportion of space they occupy (landmarks 8, 9, and 22); a slight expansion on both sides of the intra supraocular scales (landmarks 8, 11, and 14 on the right side, and landmarks 9, 12, and 15 on the left side); another significant contraction in the scales at the crown of the head, right in the center at the level of the back of the supraocular scales (landmarks 16 and 17); and finally, the most notable expansion in the anterior sector of the head (landmarks 18-21) (Fig. 2A).

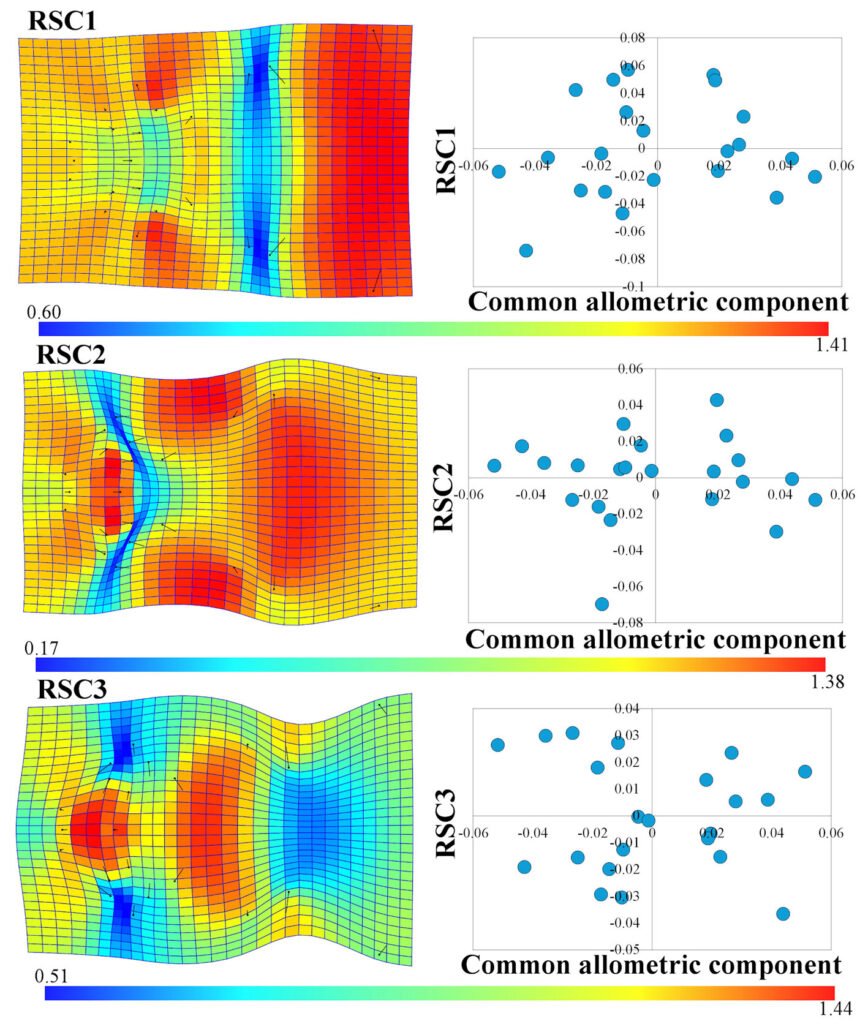

To interpret the variation not related to size in the head shape of C. triseriatus, we used the first 3 RSCs, as these explained 66.30% of the variation (RSC1 = 37.44%, RSC2 = 15.73%, RSC3 = 13.13%). The principal sources of variation in RSC1 are an expansion of the prefrontal scales to the external edges (landmarks 10-13), a significant contraction between the first and fourth row of scales on the crown of the head (landmarks 16-19), and the most important source of variation in this component was an expansion in the posterior sector of the head (landmarks 20 and 21) (Fig. 3), similar to the pattern observed in the CAC (Fig. 2B). In RSC2, 3 important expansions occur throughout the head of C. triseriatus: one in the intercanthal scales (landmarks 5, 6, 8, 9, and 22), a second in the supraocular scales (landmarks 10, 11, 14, and 16 on the right side and landmarks 12, 13, 15, and 17 on the left side of the head), and the last one in the middle of the head in the scales of the crown (Fig. 3). Lastly, in RSC3, an important expansion occurs at the center of the snout (landmarks 1-9), delimited on both sides by a contraction in the prefrontal scales (landmarks 4, 11, and 10 on the right side and landmarks 7, 12, and 13 on the left side); another important expansion occurs in the first 4 rows of the scales on the crown of the head (landmarks 16-19), followed posteriorly by a contraction (landmarks 20 and 21) (Fig. 3).

The standard deviations of the CAC (σ = 0.0288) and the first 3 RSCs (RSC1 σ = 0.0356, RSC2 σ = 0.0231, RSC3 σ = 0.0211) indicate that there are sources of variation in the head shape of C. triseriatus that are significant just as the size-related variation, particularly those contained in RSC1 (Fig. 3).

Figure 2. A, thin plate spline graph and Jacobian expansion factor explaining the allometric changes in the head shape of Crotalus triseriatus; B, Common allometric pattern in the head shape of Crotalus triseriatus and a graphic scheme of the main changes between young individuals and adults.

Discussion

According to our results, Crotalus triseriatus exhibits positive allometry in head shape, with important ontogenetic changes occurring throughout the entire head. Our analysis revealed that the CAC explains approximately 49.92% of the variation in head shape of C. triseriatus, indicating that size is a major source of variation. This appears to be a common pattern in snakes (Abegg et al., 2020; Lucchini et al., 2020; Murta-Fonseca & Fernandes, 2016), though the specific ways in which the head shape varies can differ within species. In C. triseriatus, the primary expansions occur in the posterior region of the head, a pattern consistent with other viperids (Lucchini et al., 2020), while contractions are observed mainly along the sagittal plane. In contrast, species from other families display more prominent snout expansions and modifications in the mid anterior-posterior section of the head (Abegg et al., 2020; Murta-Fonseca & Fernandes, 2016). These disparities may be attributed to the natural history of different species, as allometric trajectories are shaped by ecological factors such as diet or microhabitat preferences (Kaliontzopoulou et al., 2012; Simonsen et al., 2017). In snakes for which allometry in head shape has been analyzed through geometric morphometrics, it has been shown that semi-fossorial and aquatic habits primarily drive changes in the mid-section of the head (Abegg et al., 2020; Murta-Fonseca & Fernandes, 2016). In contrast C. triseriatus, a completely terrestrial species (Campbell & Lamar, 2004), shows more pronounced changes in the posterior part of the head. This suggests that environmental factors may impact head shape modifications in species adapted to different habitats, concretely in C. triseriatus, recent work on multiple populations has confirmed a significant environment–head shape association within this species (Caballero‑Viñas et al., 2025).

In C. triseriatus, the allometric changes observed in the snout may also be related to ontogenetic dietary shifts. Neonates primarily consume ectothermic prey, such as amphibians and lizards, while adults predominantly prey on mammals (Mociño-Deloya et al., 2014). Ontogenetic cranial changes associated with diet are well-documented in snakes, as these modifications are necessary to develop a wider gape and enhanced jaw musculature for prey capture (Patterson et al., 2021; Vincent et al., 2007). Such changes highlight the importance of head shape adaptations throughout an organism life to optimize survival. The greater expansion in the posterior part of the head likely reflects the development of venom glands and the muscularis compressor glandulae, which in adults may occupy a proportionally larger area of the head. Further studies conducting a direct anatomical assessment of allometric changes in the venom delivery system though dissection, are required to confirm that relationship. This anatomical adaptation likely enhances predatory efficiency, allowing adults to capture and subdue larger prey (such as mammals) as they grow. The hypothesis that ontogenetic dietary shifts or broader predatory requirements are the primary drivers of allometric variation in C. triseriatus is further supported by evidence that in Crotalus, allometry in head shape is linked to the kinematics of predatory strikes, specifically, maximum strike velocity (positive allometry) and the proportion of the body involved in the strike, as well as timing variables (negative allometry), change as rattlesnakes grow (LaDuc, 2003).

Figure 3. Thin plate spline graph and Jacobian expansion factor explaining the 3 first residual shape components of the head in Crotalus triseriatus and graphs of CAC vs. RSC.

The residual shape components in C. triseriatus head shape, which account for the remaining 50.07% variation that is not explained by size, highlights significant shape differences unrelated to size. This suggests that while size is a key factor, other important sources of variation influence head morphology. In amphibians and reptiles, head shape variation has been linked to factors such as phylogenetic history, habitat use (Openshaw & Keogh, 2014), sexual dimorphism (Alarcón-Ríos et al., 2017), and dietary or ecological interactions (Alarcón-Ríos et al., 2017; Segall et al., 2020; Urošević et al., 2014). This raises a fundamental question: if allometry explains a significant portion (half) of head shape variation in C. triseriatus and this is driven by predatory requirements, is it not ultimately ecology that explains this variation more than size by itself? In other words, do ecological interactions adapt to changes in size, or does size adapt to ecological niches available? The answer lies in a bidirectional relationship. Ecological interactions can shape allometric trajectories (Maestri et al., 2015); that is, certain traits may adapt to available resources, predation pressures, or competition as an organism grows, thus growth itself is limited by ecological constraints. However, allometry often acts as an evolutionary constraint, limiting morphological variation by imposing functional requirements (Huxley, 1932). In C. triseriatus, the strong correlation between size and head shape likely reflects functional limitations, particularly regarding prey capture and venom delivery. These evolutionary constraints imply that although head shape evolves in response to ecological pressures, these changes are not entirely free to vary but are shaped by underlying allometric relationships that ensure functionality. Further research into the “what came first?” question is necessary to better understand the role of allometry as an evolutionary constraint and the extent to which ecology constrains allometry.

The allometric changes in the head shape of C. triseriatus demonstrated to be a major source of variation in this species, highlighting the importance of allometry as an evolutionary constraint. In a predator such as rattlesnakes, predatory efficiency is closely linked to morphological adaptations, particularly in the head and jaw regions. Our findings suggest that ontogenetic changes in head shape are not merely a consequence of growth but instead reflect functional adjustments necessary for successful predation. As individuals grow, their ability to capture and process larger prey increases, which likely enhanced survival, just as has been stated in crocodilians (Barrios-Quiroz et al., 2012; Falcón-Espitia & Jerez, 2021). Moreover, the observed posterior expansion of the head in C. triseriatus, coupled with the contractions along the sagittal plane, could underscore the specialized adaptations linked to venom delivery and jaw musculature development. These morphological adjustments not only facilitate the consumption of larger mammalian prey but may also influence predator-prey dynamics and human-snake interactions by modulating strike performance and venom efficiency. Understanding these allometric trajectories is therefore crucial for both ecologically informed management of rattlesnake populations and for mitigating human-wildlife conflict.

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted under the Semarnat permit SGPA/DGVS/10352/21. We are also grateful to Conahcyt for the doctoral scholarship awarded to AGB. Finally, we thank the students of the Herpetology Laboratory for their support during fieldwork.

References

Abegg, A., Passos, P., Mario-da-Rosa, C., Azevedo, W., Malta-Borges, L., & Bubadué, J. (2020). Sexual dimorphism, ontogeny and static allometry of a semi-fossorial snake (genus Atractus). Zoologischer Anzeiger, 287, 95–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcz.2020.05.008

Alarcón-Ríos, L., Velo-Antón, G., & Kaliontzopoulou, A. (2017). A non-invasive geometric morphometrics method for exploring variation in dorsal head shape in urodeles: Sexual dimorphism and geographic variation in Salamandra salamandra. Journal of Morphology, 278, 475–485. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmor.20643

Álvarez-Lopeztello, J., Rivas-Manzano, I. V., Aguilera-Gómez, L. I., & González-Ledesma, M. (2016). Diversity and structure of a grassland at El Cerrillo, Piedras Blancas, Estado de México, Mexico. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 87, 980–989. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmb.2016.06.006

Balaguera-Reina, S. A., Mason, B. M., Brandt, L. A., Hernández, N. D., Daykin, B. L., McCaffrey, K. L. et al. (2024). Ecological implications of allometric relationships in American alligators (Alligator mississippiensis). Scientific Reports, 14, 6140. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-56798-5

Barrios-Quiroz, G., Casas-Andreu, G., & Escobedo-Galván, A. H. (2012). Sexual Size dimorphism and allometric growth of Morelet’s crocodiles in captivity. Zoological Science, 29, 198–203. https://doi.org/10.2108/zsj.29.198

Caballero-Viñas, C., Arenas, S., Jaramillo-Alba, J. L., Pérez-Mendoza, H. A., Manjarrez, J., Domínguez-Vega, H. et al. (2025). Mexican dusky rattlesnakes (Crotalus triseriatus) on Mexican sky islands: morphometric variation and operative temperature relationships with local environmental variables. Biologia, 80, 1389–1406. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11756-025-01905-8

Campbell, J. A., & Lamar, W. W. (2004). The venomous reptiles of the western hemisphere. Ithaca, New York: Comstock Publishing Associates.

Castillo-Juárez, J. L., Vásquez-Cruz, V., Taval-Velázquez, L. P., Avalos-Vela, R., & Lara-Hernández, F. A. (2021). Notas de distribución e historia natural de Crotalus triseriatus (Viperidae) en la región de las altas montañas, Veracruz y en el estado de Puebla. Revista Latinoamericana de Herpetología, 4, 133–139. https://doi.org/10.22201/fc.25942158e.2021.02.213

Champely, S. (2020). pwr: Basic Functions for Power Analysis. Université de Lyon, Lyon. Retrieved 13 may, 2025 from: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/pwr/index.html

Dodson, P. (1975). Functional and ecological significance of relative growth in Alligator. Journal of Zoology, 175, 315–355. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7998.1975.tb01405.x

Dos Santos, M. M., Klaczko J., & da Costa-Prudente, A. L. (2022). Sexual dimorphism and allometry in Malacophagus snakes (Dipsadidae: Dipsadinae). Zoology (Jena), 153, 126026. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.zool.2022.126026

Dryden, I. L., & Mardia, K. V. (1998). Statistical shape analysis. Chichester, England: Wiley.

Falcón-Espitia, N., & Jerez, A. (2021). The skull of Caiman crocodilus fuscus: Allometric andontogenetic shifts. Acta Biológica Colombiano, 27, 458–463. https://doi.org/10.15446/abc.v27n3.90810

Gómez-Benitez, A. (2023). Inestabilidad en el desarrollo y canalización de una comunidad de reptiles en un hábitat perturbado (Ph.D. Thesis). Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México. Estado de México, Mexico.

Gould, S. J. (1966). Allometry and size in ontogeny and phylogeny. Biological Review, 41, 587–640. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-185X.1966.tb01624.x

Hammer, Ø., Harper, D. A. T., & Paul, D. R. (2001). Past: Paleontological Statistics Software Package for Education and Data Analysis. Palaeontologia Electronica, 4, 1–9.

Hipsley, C. A., & Müller, J. (2017). Developmental dynamics of ecomorphological convergence in a transcontinental lizard radiation. Evolution, 71, 936–948. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.13186

Hipsley, C. A., Rentinck, M. N., Rödel, M. O., & Müller, J. (2016). Ontogenetic allometry constrains cranial shape of the head-first burrowing worm lizard Cynisca leucura (Squamata: Amphisbaenidae). Journal of Morphology, 277, 1159–1167. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmor.20564

Huxley, J. S. S. (1932). Problems of relative growth. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Kaliontzopoulou, A., Adams, D. C., van der Meijden, A., Perera, A., & Carretero, M. A. (2012). Relationships between head morphology, bite performance and ecology in two species of Podarcis wall lizards. Evolutionary Ecology, 26, 825–845. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10682-011-9538-y

Klingenberg, C. P. (2011). MorphoJ: an integrated software package for geometric morphometrics. Molecular Ecology Resources, 11, 353–357. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-0998.2010.02924.x

LaDuc, T. J. (2003). Allometry and size evolution in the rattlesnake, with emphasis on predatory strike performance (Ph.D. Thesis). The University of Texas at Austin, USA.

Le Verger, K., Hautier, L., Gerber, S., Bardin, J. P., Delsuc, F., González Ruiz, L. R. et al. (2023). Pervasive cranial allometry at different anatomical scales and variational levels in extant armadillos. Evolution, 78, 423–441. https://doi.org/10.1093/evolut/qpad214

Lucchini, N., Kaliontzopoulou, A., Val, G., & Martínez-Freiría, F. (2020). Sources of intraspecific morphological variation in Vipera seoanei: Allometry, sex, and colour phenotype. Amphibia-Reptilia, 42, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.

1163/15685381-bja10024

Maestri, R., Fornel, R., Freitas, T. R. O., & Marinho, J. R. (2015). Ontogenetic allometry in the foot size of Oligoryzomys flavescens (Waterhouse, 1837) (Rodentia, Sigmodontinae). Brazilian Journal of Biology, 75, 435–441. https://doi.org/10.1590/1519-6984.16613

Mitteroecker, P., Gunz, P., Bernhard, M., Schaefer, K., & Bookstein, F. L. (2004). Comparison of cranial ontogenetic trajectories among great apes and humans. Journal of Human Evolution, 46, 679–698. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2004.03.006

Mociño-Deloya, E., Setser, K., & Pérez-Ramos, E. (2014). Observations on the diet of Crotalus triseriatus (Mexican Dusky Rattlesnake). Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 85, 1289–1291. https://doi.org/10.7550/rmb.43908

Murta-Fonseca, R., & Fernandes, D. (2016). The skull of Hydrodynastes gigas (Duméril, Bibron & Duméril, 1854) (Serpentes: Dipsadidae) as a model of snake ontogenetic allometry inferred by geometric morphometrics. Zoomorphology, 135, 233–241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00435-015-0297-0

Ollonen, J., Khannoon, E. R., Macrì, S., Vergilov, V., Kuurne, J., Saarikivi, J. et al. (2024). Dynamic evolutionary interplay between ontogenetic skull patterning and whole-head integration. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 8, 536–551. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-023-02295-3

Openshaw, G., & Keogh, J. (2014). Head shape evolution in monitor lizards (Varanus): Interactions between extreme size disparity, phylogeny and ecology. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 27, 363–373. https://doi.org/10.1111/jeb.12299

Patterson, M. B., Wolfe, A. K., Fleming, P., Bateman, P., Martin, M. L., Sherratt, E. et al. (2021). Ontogenetic shift in diet of a large elapid snake is facilitated by allometric change in skull morphology. Evolutionary Ecology, 36, 489–509. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10682-022-10164-x

Pélabon, C., Firmat, C., Bolstad, G., Voje, K., Houle, D., Cassara, J. A. et al. (2014). Evolution of morphological allometry. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1320, 58–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/10.1111/nyas.12470

Pretzsch, H. (2009). Re-evaluation of allometry: State-of-the-art and perspective regarding individuals and stands of woody plants. In U. Lüttge, W. Beyschlag, B. Büdel, & D. Francis (Eds.), Progress in botany (pp. 339–369). Heidelberg, Germany: Springer.

R Core Team (2021). R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna. recovered 13 may, 2025 from: https://www.R-project.org/

Ramírez-Bautista, A., Hernández-Salinas, U., García-Vázquez, U. O., Leyte-Manrique, A., & Canseco-Márquez, L. (2009). Herpetofauna del valle de México: diversidad y conservación. Pachuca, Hidalgo: Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Hidalgo/ Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad.

Segall, M., Cornette, R., Godoy-Diana, R., & Herrel, A. (2020). Exploring the functional meaning of head shape disparity in aquatic snakes. Ecology and Evolution, 10, 6993–7005. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.6380

Simonsen, M. K., Siwertsson, A., Adams, C. E., Amundsen, P. A., Præbel, K., & Knudsen, R. (2017). Allometric trajectories of body and head morphology in three sympatric Arctic charr (Salvelinus alpinus (L.)) morphs. Ecology and Evolution, 7, 7277–7289. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.3224

Strelin, M. M., & Diggle, P. K. (2022). Within-individual leaf allometry and the evolution of leaf morphology:

A multilevel analysis of leaf allometry in temperate Viburnum (Adoxaceae) species. Evolution & Development, 24, 145–157. https://doi.org/10.1111/ede.12414

Stroud, J. T., Petherick, A., Krasnoff, B., Walker, K., Suh, J. J., & Losos, J. B. (2023). Signal size allometry in Anolis lizard dewlaps. Biology Letters, 19, 20230160. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2023.0160

Urošević, A., Ljubisavljević, K., & Ivanović, A. (2014). Variation in skull size and shape of the Common wall lizard (Podarcis muralis): Allometric and non-allometric shape changes. Contributions to Zoology, 83, 67–77. https://doi.org/10.1163/18759866-08301003

Vincent, S., Moon, B. R., Herrel, A., & Kley, N. (2007). Are ontogenetic shifts in diet linked to shifts in feeding mechanics? Scaling of the feeding apparatus in the banded watersnake Nerodia fasciata. Journal of Experimental Biology, 210, 2057–2069. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.02779

Voje, K. L., Bell, M. A., & Stuart, Y. E. (2022). Evolution of static allometry and constraint on evolutionary allometry in a fossil stickleback. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 35, 423–438. https://doi.org/10.1111/jeb.13984

Whitlock, M. C., & Schluter, D. (2008). The analysis of biological data. New York: Roberts and Company Publishers.