Mónica E. Riojas-López a, Eric Mellink b, *, Moisés Montes-Olivares b

a Universidad de Guadalajara, Centro Universitario de Ciencias Biológicas y Agropecuarias, Departamento de Ecología, C. Ramón Padilla Sánchez Núm. 2100, 45100 Zapopan, Jalisco, Mexico

b Centro de Investigación Científica y de Educación Superior de Ensenada, Departamento de Biología de la Conservación, Carretera Ensenada-Tijuana Núm. 3918, Zona Playitas, 22860 Ensenada, Baja California, Mexico

*Corresponding author: emellink@cicese.mx (E. Mellink)

Received: 23 October 2023; accepted: 9 April 2024

Abstract

Intermittent and ephemeral xeroriparian systems cover less than 1% of continental North America and are critical for wildlife in arid and semi-arid areas but are understudied and absent from conservation plans. We report the diversity of birds in 3 xeroriparian systems of the Mexican Altiplano during the non-breeding season and the habitat variables that influence them. Of the 48 documented species in this study, we have recorded 15 only in these systems, throughout our long-time research in the region. Bird communities were positively influenced by minimum and maximum height of shrubs and trees and negatively by canopy cover. The communities were grouped in one gradient from lower richness in rocky, entrenched streams, with closed canopy and little herbaceous vegetation, to greater richness in wide, open streams, with abundant herbaceous plants, and in a second gradient, from insectivorous to granivorous birds. Our study covered habitats not considered in other similar studies in Mexico and revealed that at the landscape level, ephemeral and intermittent xeroriparian systems could play a crucial role in conservation given that the systems studied covered approximately 0.1% of the area but hosted 20% of the region’s land bird species and, among migrants, especially Spring migrants.

Keywords: Arid lands; Semiarid lands; Llanos de Ojuelos; Anthropized landscapes; Migratory birds

© 2024 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Biología. Este es un artículo Open Access bajo la licencia CC BY-NC-ND

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Los sistemas xeroribereños efímeros e intermitentes son hábitats clave para comunidades de aves en la temporada no reproductiva en un paisaje semiárido mexicano

Resumen

Los hábitats xeroribereños intermitentes y efímeros cubren menos de 1% de la superficie continental de Norteamérica y son críticos para la fauna silvestre de zonas áridas y semiáridas, pero están poco estudiados y ausentes de planes de conservación. Reportamos la diversidad de aves en 3 sistemas xeroribereños del Altiplano Mexicano durante la temporada no reproductiva y las variables del hábitat que influyen. De 48 especies documentadas, hemos registrado 15 solo en sistemas xiroribereños en muchos años de investigación en la región. Arbustos y árboles más altos tuvieron influencia positiva en la comunidad de aves, mientras que doseles cerrados la tuvieron negativamente. Las comunidades se agruparon de menor riqueza en arroyos rocosos y encañonados con dosel cerrado y poca vegetación herbácea, a mayor riqueza en arroyos amplios y abiertos con abundantes herbáceas, y en un segundo gradiente, de aves insectívoras a granívoras. Nuestro estudio cubrió hábitats no considerados en otros trabajos similares en México y reveló que a nivel de paisaje, los sistemas xeroribereños efímeros e intermitentes podrían ser importantes en la conservación: los sistemas estudiados cubrían aproximadamente 0.1% del área, pero albergaron 20% de las especies de aves terrestres de la región, y entre especies migrantes, especialmente las de primavera.

Palabras clave: Zonas áridas; Zonas semiáridas; Llanos de Ojuelos; Paisajes antropizados; Aves migratorias

Introduction

Riparian systems are plant communities that develop as a result of perennial, intermittent, or ephemeral surface or subsurface water (Krueper, 1993). These systems are one of the rarest habitats in North America and cover less than 5% of the continental land mass (Krueper, 2000). Despite their rarity, throughout the world, riparian systems are extremely important because of their disproportionate contribution, relative to area, for biodiversity conservation (Arizmendi et al., 2008; Carlisle et al., 2009; Hinojosa-Huerta et al., 2013; Kirkpatrick et al., 2009; Knopf, 1985; Krueper 1993, 1996, 2000; Seymour & Simmons, 2008; Skagen et al., 1998; Wilson in Knopf et al., 1988). They also contribute to enhance connectivity in fragmented landscapes particularly for resident and non-migrating birds (Şekercioǧlu et al., 2015).

Dryland riparian systems are known as xeroriparian, and whether the streams that originate them are perennial, or non-perennial, they are notoriously different from the surrounding landscape. In the western United States, in the 1980s they covered < 1% of the land (Knopf et al., 1988). However, they are very important for wildlife in semiarid and arid regions, and support much of the biotic diversity in semiarid and arid southwestern USA (Sánchez-Montoya et al., 2017; Szaro & Jakle, 1985), sometimes having bird population densities and species diversity as much as 5 to 10 times those of nearby desert non-riparian systems (Johnson & Haight, 1985; Levick et al., 2008). In these regions, migrating birds depend on water, habitat, and food that are restricted spatially and temporally (Carlisle et al., 2009). Up to 70% of all bird species use riparian systems in drylands at some point in their life cycle (Krueper, 1996), and > 60% of the neotropical migratory bird species use them either as stopover areas or as breeding habitats (Kirkpatrick et al., 2009; Krueper, 1993; Skagen et al., 1998).

Although non-perennial streams are the most widespread flowing-water ecosystem throughout the world (Datry et al., 2017), ecological studies on xeroriparian systems had focused mostly on permanent streams (Hinojosa-Huerta et al., 2013; Neate-Clegg et al., 2021; Szaro & Jakle, 1985). Overall, riparian systems created and maintained by intermittent and ephemeral streams are understudied and the scientific literature on their ecological role is very limited (Datry et al., 2017; Levick et al., 2008; McDonough et al., 2011; Sánchez-Montoya et al., 2017). Not only are they understudied, but they also are poorly considered in conservation planning. For example, intermittent and ephemeral streams are recognized in California´s “Riparian Bird Conservation Plan” (Riparian Habitat Joint Venture, 2004), but only perennial ones are included in its actions. Such neglect of largely intermittent or ephemeral riparian systems can lead to serious shortcomings in conserving biodiversity.

Xeroriparian systems are important not only for biodiversity, but the water in them has been a coveted commodity for human survival and productive activities, and, in consequence, they have suffered extreme, widespread modification. As a result, within the past 100 years an estimated 95% of lowland riparian habitat in western North America has been altered, degraded, or destroyed (Krueper, 2000). In arid and semiarid regions where water is naturally scarce, livestock and agricultural demands for it result in riparian systems being affected with particular severity (Patten et al., 2018). Mexico´s arid and semiarid Central Altiplano is no exception, and its riparian systems have been transformed by their water being diverted for human needs with no consideration for the conservation of wildlife (Mellink & Riojas-López, 2005).

Published information on non-urban xeroriparian systems is scarce, and for Mexico, it is even scarcer. The only 3 articles in the scientific literature that we have found on birds in xeroriparian systems in Mexico focus on perennial systems (Arizmendi et al., 2008; Hinojosa-Huerta et al., 2013; Pérez-Amezola et al., 2020). Three highly relevant nationwide biodiversity conservation sources surprisingly do not mention riparian systems: 1) A 1998 listing of Mexico´s natural protected areas (Conabio, 1998); 2) the extensive treatise on the use and conservation of the terrestrial ecosystems of Mexico (Challenger, 1998); and 3) the 3 volume, 1,739 pages, Estado de Mexico´s biodiversity and its conservation threats (Conabio, 2008). This suggests that in addition to being understudied, the importance of riparian systems in Mexico has not been fully appreciated.

One of the least studied landscape components of the southern Mexican Altiplano, including the Llanos de Ojuelos, are xeroriparian systems. This region is strongly anthropized and natural habitats have been greatly affected by agriculture and livestock, including the riparian systems in it. Currently, those riparian systems in the region that have not disappeared because of water channelization and damming, are subject to browsing and trampling by livestock, and by the extraction of wood, sand, gravel, and water. However, the remaining xeroriparian systems in the southern part of this Altiplano, even in their impacted form, continue to provide habitat for wildlife (Riojas-López & Mellink, 2019; Riojas-López et al., 2019).

Birds that use xeroriparian systems in the southern part of the Altiplano are little known, and the limited knowledge about them had so far derived from occasional observations only (for example, in Riojas-López & Mellink, 2019). As pointed out in the literature, intermittent and ephemeral xeroriparian systems are keystone habitats for biodiversity, although their role in Mexico has not been assessed. This keystone role can be expected to be especially important in a country like Mexico where arid and semiarid conditions cover half of its territory (Challenger, 1998). This information void precludes the design of pertinent and timely conservation plans for these habitats and the wildlife that uses them. Hence, in this study we aimed at documenting the birds that use xeroriparian systems in the highly anthropized southern part of the Altiplano, and the habitat characteristics that drive their assemblages during the non-breeding season. We studied 3 xeroriparian systems during the non-breeding bird season, with 2 objectives: 1) document the species richness, abundance and their temporal variation, and 2) determine the relationship between bird species richness and abundance and vegetation characteristics. In the context of an alarming decline of bird populations in North America (Rosenberg et al., 2019), studies like this are needed as a baseline to monitor the trends of bird populations that depend on the persistence of xeroriparian systems. The urgency of this need is increased because of the ongoing climate change in which drier and hotter regimes are predicted.

Materials and methods

The study was carried out in the Llanos de Ojuelos, at the convergence of the states of Jalisco, Zacatecas, Aguascalientes, San Luis Potosí and Guanajuato (Fig. 1). This area is a semi-arid tableland at 1,900-2,600 m altitude with a geomorphology of low mountains and valleys (Nieto-Samaniego et al., 2005). Three climatic seasons occur: dry cold (November-February), dry hot (April-May), and rainy (June to September); March and October are intermediate (Mellink et al., 2016), with an average annual temperature at the Ojuelos de Jalisco, Jalisco, meteorological station (1988-2008) of 15 °C, annual rainfall of 681 mm, and tank evaporation higher than precipitation all months of the year. The area has endorreic drainage, and rainwater flows through ephemeral streams or, in some cases, as sheet flows and collects in seasonal pools or is stored in cattle watering tanks and dams. Historically, springs were common, but the majority have disappeared (Mellink & Riojas-López, 2005).

The natural vegetation of the region is composed of grasslands (42.6% of the region’s surface), xerophilous shrublands (15.66%) and stands of dwarf oaks (Quercus spp.; 4.61%). Grasses of the genera Bouteloua, Aristida, Lycurus, and Mulhenbergia are the most common components of grasslands. Catclaws (Mimosa spp.), silver dalea (Dalea bicolor), leatherstem (Jatropha dioica), huizache (Vachellia spp.), arborescent nopales (Opuntia spp.), Peruvian pepper tree (Schinus molle), and yucca (Yucca spp.) form the shrub and arborescent layers (Harker et al., 2008; MER-L & EM pers. obs.).

Livestock and agriculture are the main productive activities in the Llanos de Ojuelos and have transformed the region´s landscape since the arrival of Spanish conquerors 450 ~ 500 years ago (Mellink & Riojas-López, 2020). Currently, approximately 35.5% of the surface of the municipalities of Ojuelos de Jalisco, Jalisco, and Pinos, Zacatecas is devoted to rain-fed farming of mostly corn, beans and fruit-oriented nopal orchards, while sheep, goats, cows, and horses graze and browse throughout the region (Pers. obs.).

Figure 1. The Llanos de Ojuelos region, southern Mexican Altiplano, indicating the 3 xeroriparian systems where bird communities were studied during the 2019-2020 non-breeding season (in white lettering), reference localities (in green upper/lowercase), and states (in green small caps).

This study was performed in 3 independent and geographically separated xeroriparian systems (localities), through visual surveying of birds during the 2019-2020 non-breeding season (Fig. 1). The localities were selected based on them being safe, accessible, and independent of each other (i.e., that their channels were not connected), and that the owners allowed us to work in them. In each system, we established 3 survey sections along the stream, with different characteristics. These xeroriparian systems, from north to south, were: La Laborcilla (Table 1). Its stream is ephemeral and flows southeast from the low mountain range that stretches between La Montesa and El Nigromante, in the municipality of Pinos. It has a straight riverbed (Sinuosity Index [SI], sensu Rosgen, 1994, < 1.1) and its slope is 8.4%. Boulders cover most of the streambed. The ground in the area adjacent to stream is mostly rocky and covered by shrubland whose major components are junipers (Juniperus deppeana), dwarf oaks, central Mexico yucca, and huisaches. The range is used for the raising of sheep and goats, along with a few cattle. Rancho Santoyo (Table 2). This is a slow-flowing straight stream (SI < 1.1), on sandy and tepetate streambed and low slope (2.4%), with permanent water in parts of it, provided by a permanent spring. The surroundings are overgrazed grassland with huisaches, and shrubland with arboreal nopales, huisaches, and pepper trees. The range is used to raise fighting-bull cattle. La Colorada (Table 3). Draining south from the Mesa del Toro, near Ojuelos, the sandy and tepetate streambed of this system is sinuous (SI = 1.1-1.3), with an overall slope of 2.3%. Its surroundings are of grasslands, some overgrazed and some in good condition, with some huisaches and shrubby nopales, and farmland. The range is used mostly for the raising of fine horses, while the nearby farmland is used to grow beans and chilies.

Table 1

Morphological characteristics and vegetation composition, based on the most common tree and shrub species of different sections of the xeroriparian system of La Laborcilla, in the Llanos de Ojuelos, southern part of the Mexican Altiplano, whose birds were studied during the 2019-2020 non-breeding season. Streambed values are mean ± standard error.

| Section | Coordinates | Streambed | Description | |

| Lat./Long. | Width (m) | Depth (m) | ||

| Upper | 22°5’32”-101°43’33” | 25.8 ± 2.2 | 10.2 ± 2.2 | A deep ravine with dwarf oaks (Quercus spp.) and junipers (Juniperus deppeana), with dispersed maguey (Agave sp.) and sotol plants (Dasylirion spp.). |

| Middle | 22°5’26”-101°43’27” | 26.1 ± 0.5 | 10.6 ± 1.0 | A deep ravine, but here the dominant treelike form were junipers and huizaches (Vachellia spp.), with dispersed maguey and sotol plants. |

| Lower | 22°5’17”-101°43’4” | 25.0 ± 3.9 | 2.4 ± 0.5 | A shallow ravine whose main arboreal component were junipers, with interspersed yuccas (Yucca spp.), and a shrub layer composed of dispersed leatherstem (Jatropha dioica), jimmyweed (Isocoma spp.), and catclaws (Mimosa spp.). |

We surveyed the birds monthly from September 2019 to March 2020, covering the entire non-breeding season: the migratory seasons of Autumn and Spring, as well as the Winter in-between. Birds were identified and counted for 3 consecutive days at each study system, once per month. Bird inventorying was carried out for 2 hours in the afternoon ending at sunset and 2 hours the following morning starting at sunrise, as these are the periods of highest bird activity. Bird nomenclature and taxonomic arrangement follows Chesser et al. (2023).

Table 2

Morphological characteristics and vegetation composition, based on the most common tree and shrub species of different sections of the xeroriparian system of Rancho Santoyo, in the Llanos de Ojuelos, southern part of the Mexican Altiplano, whose birds were studied during the 2019-2020 non-breeding season. Streambed values are mean ± standard error.

| Section | Coordinates | Streambed | Description | |

| Lat./Long. | Width (m) | Depth (m) | ||

| Upper | 21°55’1”-101°47’32” | 50.9 ± 2.5 | 3.8 ± 0.3 | A relatively wide and moderately deep riverbead, densely vegetated with tall willows (Salix bonplandiana), cottonwoods (Populus fremontii) in addition to pepper trees (Schinus molle) and huizaches, interspersed with patches of ragwort (Senecio spp.). |

| Middle | 21°55’10”-101°47’31” | 38.0 ± 2.6 | 1.7 ± 0.5 | A wide and shallow part of the riverbed, covered by peppertrees and ragwort. |

| Lower | 21°55’40”-101°47’25” | 12.4 ± 1.5 | 0.7 ± 0.5 | A very thin and shallow canal, flanked by large peppertrees, with huisaches, and some catclaw and low nopales (Opuntia spp.). |

Table 3

Morphological characteristics and vegetation composition, based on the most common tree and shrub species of different sections of the xeroriparian system of La Colorada, in the Llanos de Ojuelos, southern part of the Mexican Altiplano, whose birds were studied during the 2019-2020 non-breeding season. Streambed values are mean ± standard error.

| Section | Coordinates | Streambed | Description | |

| Lat./Long. | Width (m) | Depth (m) | ||

| Upper | 21°47’48”-101°38’18” | 36.1 ± 5.9 | 4.3 ± 0.9 | A deep canyon in which the most notorious trees were dwarf oaks, with dispersed catclaws and sotol, as the most abundant shrubs. |

| Middle | 21°47’30”-101°37’34” | 75 ± 5.7 | 6.3 ± 0.8 | Semi-open deep riverbed dominated by pepper trees, with some dispersed huisaches, arborescent nopales, and willows; the most notorious shrubs were ragworts. |

| Lower | 21°47’5”-101°36’51” | 61.0 ± 8.3 | 7.0 ± 2.2 | A semi-open riverbed in which the most notorious trees were pepper trees and arborescent nopales, with some huisaches. The most visible shrubs were catclaws, some sedges and some shrubby nopales. |

Three survey stations were established in each of the 3 sections within each xeroriparian system, 40 m apart from each other and each consisting of one survey point in the center of the riverbed and 1 at the edge of the riparian habitat, looking at it. These 2 survey points allowed us to record birds that prefer the outer canopy as well as those that prefer the understory. One “day” of observation consisted of an afternoon and the following morning. We randomized the order in which the survey points were surveyed in such a way that each section was surveyed on 1 day in the first place, on 1 day in the second place, and on 1 day in the third place. For example, on day 1 survey order could be B1 [section B, station 1], A2, C3; on day 2 C1, B2, A1; and on day 3: A3, C2, B3. In some cases, riverbed survey points became darker sooner in the afternoon and lighter in the morning. Therefore, the riverbed points were surveyed before their corresponding outside station in the afternoon, and after it in the morning. Within a survey month, the same randomization was applied to the 3 xeroriparian systems, but a new randomization was performed every month. Survey order of xeroriparian systems followed logistic considerations and varied between months.

Birds at each survey point were identified and counted with 8×40 binoculars in a circle with a 20-m radius for 10 min (Brand et al., 2008; Merrit & Bateman, 2012). We did not include the birds that were observed outside or flying over the riparian system. As the best proxy of each species’ abundance in any given station we selected the highest count among the 4 counts carried out on a visit: riverbed and outside survey points, afternoon, and morning counts (Merrit & Bateman, 2012). For each section, the monthly estimate of abundance for each species was the sum of the 3 stations’ maximum values. Trophic guild and residency status of each bird species were obtained from the “The Birds of the World” series of monographs (https://birdsoftheworld.org/bow/home).

Additional to bird surveys, we measured vegetation attributes that according to the literature are important for birds (Brand et al., 2008; Powell & Steidl, 2015; Rotenberry, 1985; Wiens & Rotenberry, 1981). On 1 visit, we identified the dominant plants and measured the minimum and maximum height of shrubs and of trees. On each survey period, we determined herb cover of the ground, herb vertical density, and canopy cover. Herb cover of the ground in the region grows explosively as a result of Summer rains and dries after maturation. We used a simple scoring of 3 levels of ground cover by herbs: completely bare or nearly so, medium cover, and completely covered, or nearly so based on visual appreciation.

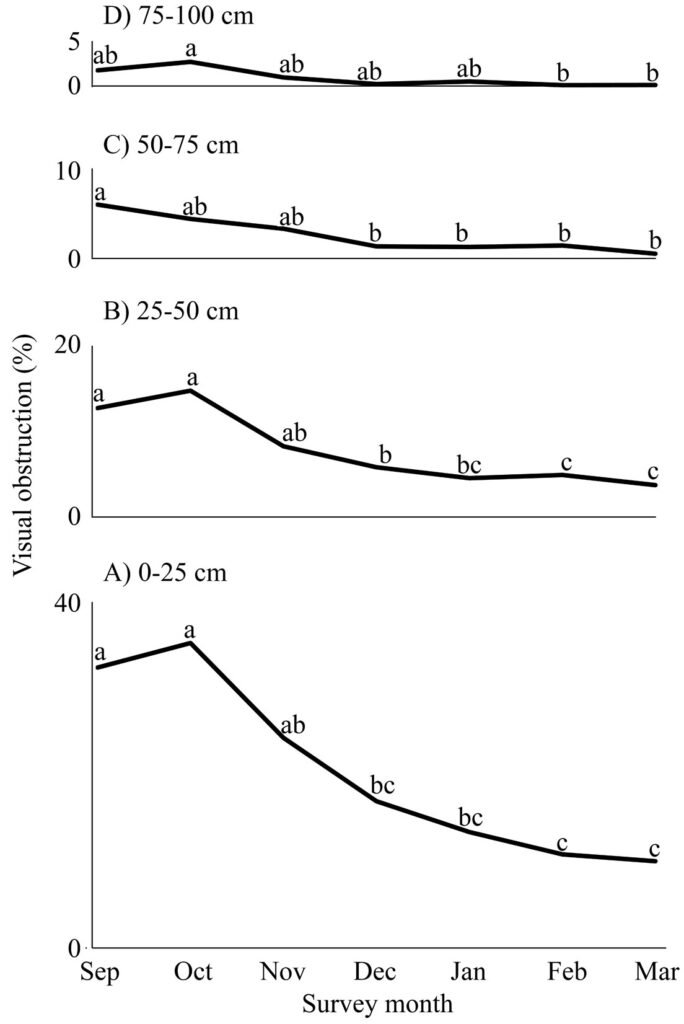

Herb vertical density was calculated with a 30-cm wide board divided into bands every 25 cm in height until 100 cm (0-25, 25-50, 50-75 and 75-100 cm). This board was placed 10 m away from each internal survey point in 4 directions, 2 parallel and 2 perpendicular to the streambed, and the percentage of visual obstruction in each band as seen from the center point was recorded (Hays et al., 1981).

Canopy cover was determined by foliage cover in 4 photographs of the canopy with an inclination of 30° from the vertical, at all streambed points. Two photographs were taken along the stream axis and 2 perpendicular to it, 1 to each side. The percentage of obstruction of the vegetation in each photograph was calculated counting number of pixels with and without vegetation using Photoshop ver. 2017.

Through an information-theoretic approach (Burnham & Anderson, 2002), we tested the effect of xeroriparian system and season (fixed effects) on richness, overall abundance, and abundance of the bird species that summed more than 10 individuals. Poisson distribution was used, and survey section was included as a random effect. We selected the best model with Akaike Information Criterion for small samples (AICc), applying the principle of parsimony when differences in AICc values were < 2.5 (Burnham & Anderson, 2002). Whenever we refer to a “best model” it implies that it was either the best or the most parsimonious model. We also used the same approach to explore the influence of vegetation attributes on the same bird variables. Before running the models, we obtained correlations between habitat variables and averaged those that were correlated > 0.85 and reviewed the new correlation values. This procedure was used to prevent any important variable for the birds from going unnoticed by not being part of the best model as a result of the variance that it would explain being partially accounted for by another, highly correlated variable which was included in such model. The final list of explanatory habitat variables included density of herbs, visual obstruction at 0-0.25 cm, 25-75 cm and 75-100 cm, minimum height of shrubs, minimum height of trees, mean and maximum height of shrubs and trees averaged, and canopy cover. Modeling was performed using pgirmess and lme4 libraries in R 3.3.1, through RStudio Ver. 1.2.5019.

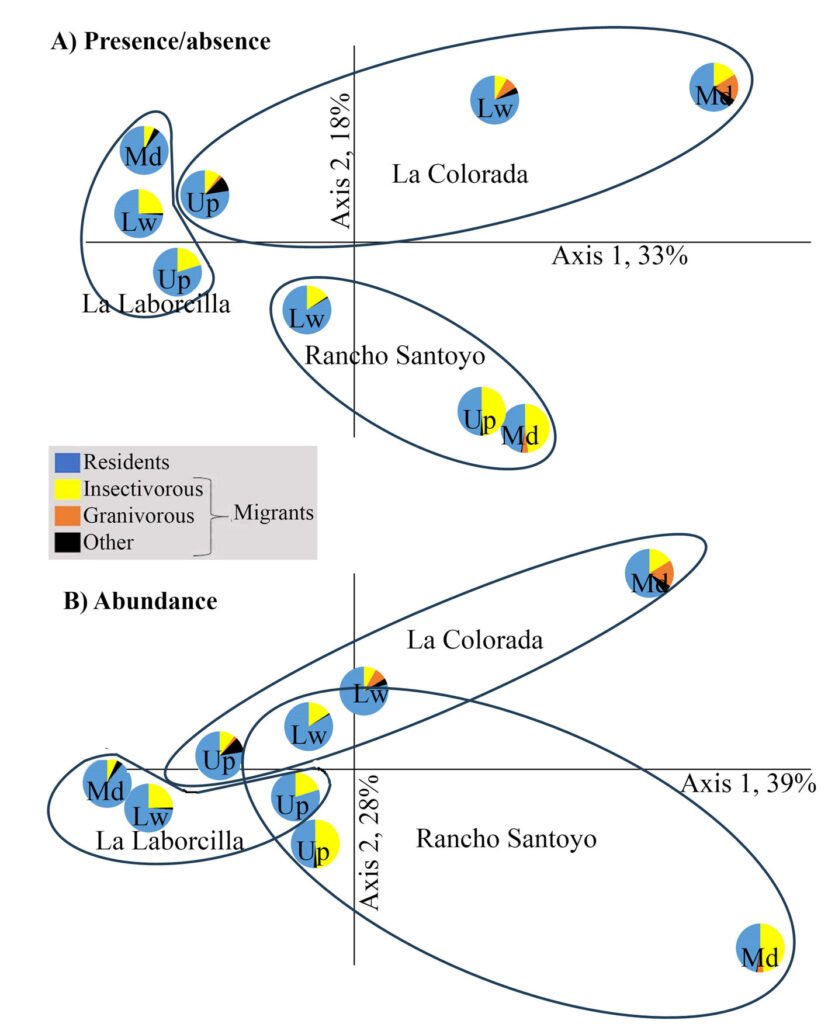

Averaged vegetation characteristics were compared between systems through analyses of variance, followed by post-hoc Tuckey tests if statistical differences were detected (p ≤ 0.05). Similarity between systems was calculated through Jaccard´s index. We arranged study sections through Principal Components Analysis (PCA) based on their birds, both on binary data (species presence/absence) and on their abundance. These analyses were done using PAST 4.03 (https://folk.universitetetioslo.no/ohammer/past).

Results

During our surveys we identified 48 species of birds, in addition to some individuals that were identified only at genus or family level, but which likely belonged to 1 of the identified species (Supplementary material 1, 2). The identified species included 30 resident and 18 migratory bird species. Twelve additional species were recorded using xeroriparian systems, but outside our surveys. The total count during surveys was 932 individuals. Spizella passerina was the most abundant species with 149 individuals (16% of total abundance). Five other species contributed between 5 and 10% of the total abundance: Corthylio calendula, Setophaga coronata, Zenaida asiatica, Psaltriparus minimus, and Aphelocoma woodhouseii (Supplementary material 2).

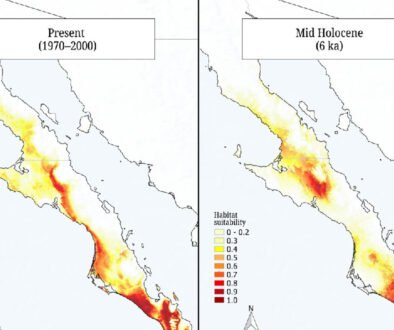

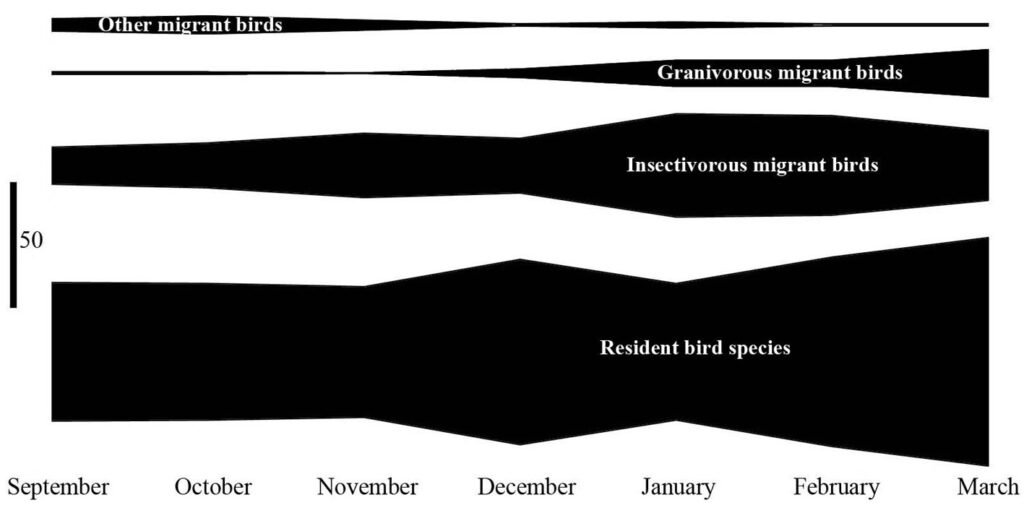

Figure 2. Overall abundance (number of individuals) of bird guilds in the Llanos de Ojuelos region, southern Mexican Altiplano, during the 2019-2020 non-breeding season in 3 xeroriparian systems.

Figure 3. Monthly abundance of all birds and birds of resident species that included survey month as part of best models exploring the influence of locality (xeroriparian system) and month, during the 2019-2020 non-breeding season in 3 xeroriparian systems in the Llanos de Ojuelos, southern Mexican Altiplano.

Figure 4. Monthly abundance of birds of migrant species that included survey month as part of best models exploring the influence of locality (xeroriparian system) and month, during the 2019-2020 non-breeding season in 3 xeroriparian systems in the Llanos de Ojuelos, southern Mexican Altiplano.

Figure 5. Total abundance of species that had location as part of the best model exploring the influence of locality and survey month, during the 2019-2020 non-breeding season in each of 3 xeroriparian systems in the Llanos de Ojuelos, southern Mexican Altiplano.

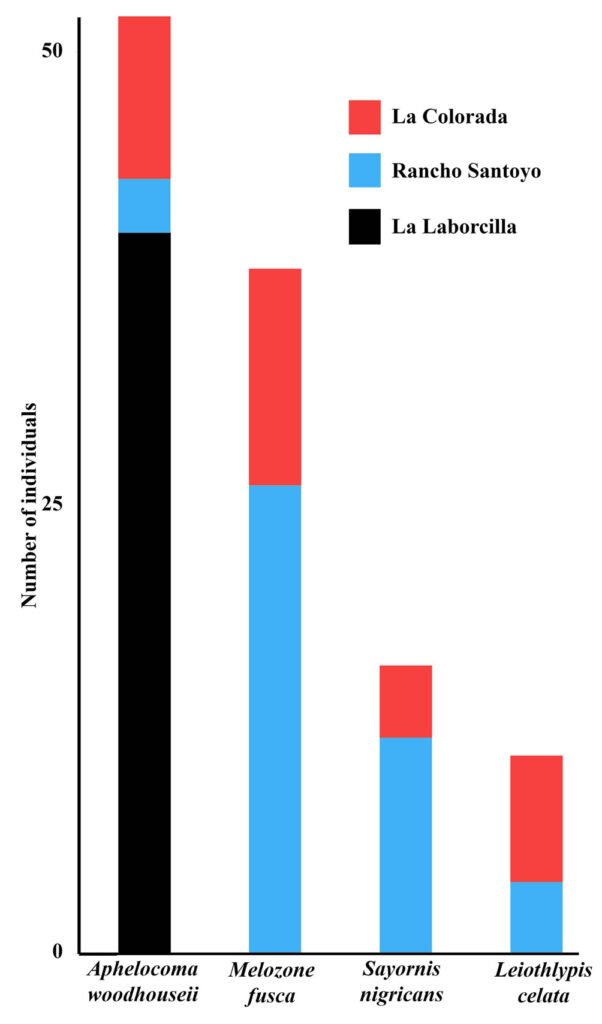

La Laborcilla had a total bird count of 213 individuals (162 of 13 resident/breeding species, 48 of 8 migrant species, and 3 of 2 unidentified species), Rancho Santoyo had 353 (197/22, 149/11, and 7/3), and La Colorada, 366 (228/27, 128/16, and 10/3). Most individuals counted were of resident species or of 1 Summer (breeding) resident species (Myiarchus cinerascens),while migrants were a smaller component of the community (Fig. 2). For species richness, the best model did not include locality nor month. The best model explaining overall bird abundance included month (Supplementary material 3), but not locality. Abundance increased from Autumn (September) to Spring (March) with some differences between guilds. Insectivore migrants increased in number into the Winter and then decreased, while granivore migrants began to arrive in December and increased until March (Fig. 2). In all these cases the month of survey was part of the best model, as it was of 11 bird species (Figs. 3, 4; Supplementary material 3). Locality was part of the best model explaining abundance in 4 cases out of 27, all of them individual species (Fig. 5; Supplementary material 3). Aphelocoma woodhouseii and Leiothlypis celata were the only 2 species whose best model included both locality and moth, while the best models for the other species did not include either variable (Supplementary material 3).

Figure 6. Total abundance of birds in different trophic guilds in 3 xeroriparian systems and 3 sections within each, during the 2019-2020 non-breeding season in the Llanos de Ojuelos, southern Mexican Altiplano. Numbers on the circles indicate richness and total abundance, while numbers on the side of the dendrograph indicate similarity between xeroriparian systems, Bird assemblages in Rancho Santoyo and La Colorada were more similar between them than to La Laborcilla (Fig. 6). In PCA graphs, the 3 sections at La Laborcilla grouped closer to each other than those of the other systems. The sections within each system grouped discreetly when binary data was used (Fig. 7 top), but groups overlapped when based on abundance (Fig. 7 bottom). The 3 systems studied differed in the resident/breeding vs. migrant composition of the communities, and sections within systems were also different (Fig. 6). Whereas Rancho Santoyo had a higher proportion of insectivore migrants than the other locations, La Colorada had a higher count of granivore migrants, and La Laborcilla had proportionally more individuals of resident species (Myiarchus cinerascens did not occur in La Laborcilla). In neither case did such patterns occur in the 3 sections of the corresponding system, but only in 2 of Rancho Santoyo’s sections and in 1 and partially in another at La Colorada.

Figure 7. Principal Component arrangement of 3 study sections in each of 3 xeroriparian systems based on their bird composition during the 2019-2020 non-breeding season in the Llanos de Ojuelos, southern Mexican Altiplano. The upper figure is based on binary data (presence/absence of species), and the lower figure, on bird abundance. Ellipses were drawn around the 3 sections of each system by hand. The legends “Up”, “Md”, and “Lw” indicate the upper, middle and lower sections of each system.

The attributes of the plant communities were different between xeroriparian systems (Table 4). La Laborcilla had significantly less ground covered by herbs, whereas Rancho Santoyo and La Colorada were not different in this aspect. La Colorada had significantly denser vegetation from 0 to 75 cm above the ground than the 2 other systems, but visual obstruction at 75-100 cm was not different between the 3 systems. The tallest shrubs and highest trees were significantly taller in Rancho Santoyo than in La Laborcilla, whereas La Colorada was not different from either, and average height both shrubs and trees was significantly greater at Rancho Santoyo than at La Laborcilla, with La Colorada being in between and statistically different from either. Canopy cover was not different between systems. Study sections were all peculiar within the systems, but only in some cases were sections significantly different (Supplementary material 4). Despite slight differences, visual obstruction at the 4 heights assessed was highest in September and October, and then decreased towards their lowest values in March (Fig. 8).

At least 1 habitat attribute was part of the best bird model in all but 3 cases (Tables 5-7), the 3 of them resident species: Zenaida asiatica, Thryomanes bewickii, and Phainopepla nitens. In all cases in which canopy cover was part of the best model, it had a negative effect on bird richness or abundance, while herb density and visual obstruction at 25-75 cm had a negative effect in most of the best models that included them (Tables 5-7). In contrast, visual obstruction at 75-100 cm and mean/maximum height of shrubs/trees had a positive effect.

Figure 8. Mean visual obstruction in 4 25-cm vertical layers, between 0 and 100 cm above the ground across 3 sections in each of 3 xeroriparian systems studied during the 2019-2020 non-breeding season in the Llanos de Ojuelos, southern Mexican Altiplano. To reflect the spatial arrangement of the information, the panels are arranged bottom to top. The height stratum to which each graph corresponds is indicated on the graph. Points on each graph with the same letter are not statistically different (p < 0.05).

Discussion

The lack of studies about the role of ephemeral and intermittent xeroriparian systems as key habitats for biodiversity conservation and potential provision of ecological services severely impairs the capability of designing and implementing timely and informed conservation actions. In this study we generated a basic understanding about the composition of bird assemblages in 3 Mexican xeroriparian systems and the habitat attributes that influence them. Our study is particularly pertinent as the results of only 3 other research projects on birds in Mexican xeroriparian systems have been published (Arizmendi et al., 2008; Hinojosa-Huerta et al., 2013; Pérez-Amezola et al., 2020), none of them including ephemeral systems.

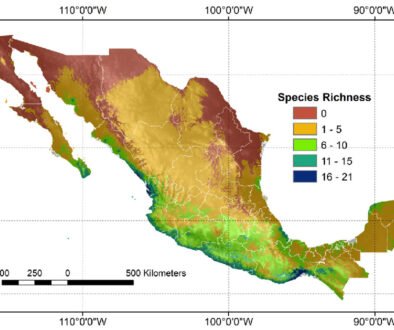

The 48 terrestrial species that we recorded represent 20% of all potential terrestrial native birds of the area, excluding swifts (family Apodidae) (based on Howell and Webb [1995]). This is relevant considering that xeroriparian systems, in general, occupy around 5% of the total land surface in western North America (Krueper, 2000), and that those we studied covered approximately 0.1% of the area in which they are located (by delineating them in Google Earth and measuring their area as well as that of the displayed image). According to Partners of Flight (2023) Campylorhynchus brunneicapillus, Spizella atrogularis, Selasphorus rufus/sasin, and Cardellina pusilla have conservation problems, while Accipiter striatus and A. cooperii are protected by Mexican law (Semarnat, 2010). The importance of xeroriparian systems in the region studied is enhanced by the fact that some otherwise woodland bird species largely depend on them, and we have not documented them in any other xeric habitats of the region (Mellink et al., 2016, 2017; Riojas-López & Mellink, 2019; Riojas-López et al., 2019).

Table 4

Vegetation attributes of 3 xeroriparian systems in the Llanos de Ojuelos, southern part of the Mexican Plateau, 2019-2020. Values are estimate ± standard error, except on maximum and minimum heights. Values of any variable with different literal were significantly different (p ≤ 0.05) according to an ANOVA + Tukey post hoc tests. Superscript “ns” indicates that the means were not significantly different.

| Site/section | Herb | Visual obstruction (%) | Hight of shrubs (m) | Height of trees (m) | Canopy | |||||||

| density (1-4) | 0-25 cm | 25-50 cm | 50-75 cm | 75-100 cm | Max | Min | Mean | Max | Min | Mean | cover (%) | |

| La Laborcilla | 1.53 ± 0.38b | 12.00 ± 4.27b | 4.22 ± 2.58b | 0.89 ± 1.06b | 0.40 ± 0.55ns | 2.63 ± 0.32b | 0.23 ± 0.10ns | 0.63 ± 0.01c | 8.37 ± 0.27b | 0.73 ± 0.26ns | 3.58 ± 0.26c | 40.40 ± 8.82ns |

| Rancho Santoyo | 2.52 ± 0.88a | 13.60 ± 16.7b | 3.03 ± 4.75b | 0.85 ± 2.38b | 0.83 ± 2.27ns | 3.55 ± 0.49a | 0.31 ± 0.08ns | 1.41 ± 0.31a | 14.65 ± 3.04a | 1.20 ± 0.44ns | 4.79 ± 0.89a | 39.50 ± 16.83ns |

| La Colorada | 2.70 ± 0.95a | 35.98 ± 17.06a | 16.04 ± 10.83a | 6.40 ± 6.32a | 1.59 ± 2.48ns | 3.14 ±0.76ab | 0.22 ± 0.06ns | 1.21 ± 0.44b | 10.36 ± 3.55ab | 0.87 ± 0.19ns | 4.54 ± 0.54b | 45.48 ±29.86ns |

These species can be considered locally xeroriparian-dependent. They are Accipiter striatus, A. cooperii, Empidonax difficilis occidentalis, Pitangus sulphuratus, Empidonax wrightii, Corthylio calendula, Turdus migratorius, Setophaga coronata, Setophaga townsendi, Piranga ludoviciana, Bubo virginianus, Sphyrapicus varius, and Cardinalis cardinalis. This was also the case of Pipilo maculatus and P. chlorurus, otherwise species of thick shrublands. The system with more xeroriparian-dependent species was La Colorada (9 species) followed by Santoyo (7) and La Laborcilla (6). However, Santoyo had more riparian-dependent individuals (139) than La Colorada (78) and La Laborcilla (45), Setophaga coronata and Corthylio calendula being the most abundant species (Supplementary material 2).

Table 5

Sign of the effects of habitat features on the bird community variables in 3 study sections in each of 3 xeroriparian systems studied during the 2019-2020 non-breeding season in the Llanos de Ojuelos, southern Mexican Altiplano. The only data indicated are that of variables included in the best or more parsimonious model under an information-theoretic approach. Blank cells are of variables not included in such models. Min. indicates minimum, and Max., maximum. Variables with correlation coefficients > 0.85 were merged before the analysis. The intercept is not shown. Actual data is presented in Supplementary material 5.

| Bird community variable | Herb | Visual obstruction (%) | Shrub Min. | Tree Min. | Shrub-tree | Canopy | ||

| Density (1-4) | 0-0.25 cm | 25-75 cm | 75-100 cm | Height (m) | Height (m) | Min./Max. (m) | Cover (%) | |

| Richness | + | – | ||||||

| Abundance | ||||||||

| Overall | – | – | + | – | ||||

| All resident species | – | – | – | |||||

| All migrants | – | + | + | |||||

| Migrant insectivorous birds | – | + | – | |||||

| Migrant granivorous birds | – | + | – |

Table 6

Sign of the effects of habitat features on the abundance of resident species of birds in 3 study sections in each of 3 xeroriparian systems studied during the 2019-2020 non-breeding season in the Llanos de Ojuelos, southern Mexican Altiplano. The only data indicated are that of variables included in the best or more parsimonious model, under an information-theoretic approach. Blank cells are of variables not included in such models. Min. indicates minimum, and Max., maximum. Variables with correlation coefficients > 0.85 were merged before the analysis. The intercept is not shown. Actual data is presented in Supplementary material 5.

| Bird response variable | Herb | Visual obstruction (%) | Shrub Min. | Tree Min. | Shrub-tree | Canopy | ||

| Density (1-4) | 0-0.25 cm | 25-75 cm | 75-100 cm | Height (m) | Height (m) | Min./Max. (m) | Cover (%) | |

| Zenaida asiatica | ||||||||

| Melanerpes aurifrons | – | |||||||

| Sayornis nigricans | + | |||||||

| Aphelocoma woodhouseii | – | – | ||||||

| Psaltriparus minimus | – | + | – | – | ||||

| Phainopepla nitens | ||||||||

| Thryomanes bewickii | ||||||||

| Mimus polyglottos | + | |||||||

| Spinus psaltria | + | + | + | – | ||||

| Spizella passerina | – | – | – | |||||

| Melozone fusca | + | |||||||

| Pipilo maculatus | – | + | – |

Table 7

Sign of the effects of habitat features on the abundance of migratory birds in 3 study sections in each of 3 xeroriparian systems studied during the 2019-2020 non-breeding season in the Llanos de Ojuelos, southern Mexican Altiplano. The only data indicated are that of variables included in the best or more parsimonious model, under an information-theoretic approach. Blank cells are of variables not included in such models. Min. indicates minimum, and Max., maximum. Variables with correlation coefficients > 0.85 were merged before the analysis. The intercept is not shown. Actual data is presented in Supplementary material 5.

| Bird response variable | Herb | Visual obstruction (%) | Shrub Min. | Tree Min. | Shrub-tree | Canopy | ||

| Density (1-4) | 0-0.25 cm | 25-75 cm | 75-100 cm | Height (m) | Height (m) | Min./Max. (m) | Cover (%) | |

| Empidonax wrightii | + | |||||||

| Corthylio calendula | – | + | ||||||

| Troglodytes aedon | + | |||||||

| Turdus migratorius | – | – | + | – | ||||

| Melospiza lincolnii | – | – | + | – | ||||

| Spizella pallida | – | + | – | + | – | |||

| Leiothlypis celata | + | |||||||

| Setophaga coronata | – | |||||||

| Cardellina pusilla | + |

Resident species increased their abundance from December through March (Figs. 2, 3), a pattern that could have been driven by 3 processes, not necessarily mutually exclusive: 1) resident species that might breed in xeroriparian habitats disperse to feed in other habitats in the region after nesting, might have begun to congregate for the upcoming breeding season, which would make the different habitats complementary (Dunning et al., 1992); 2) species like the P. maculatus might become more detectable as breeding-associated territoriality and courting behaviors develop; 3) migrating individuals of northern populations of species that locally remain resident might pass through the region in the Spring (perhaps S. passerina; Fig. 4).

The increase in abundance of the resident species as the season progressed was combined with the addition of migratory species in their northbound Winter-Spring migration. The pattern observed in our study is similar to that in the lower Colorado River in southwestern Arizona, where more birds migrate during the Spring than during the Autumn and suggests that some species migrate via different routes and/or use different habitats during the latter (Carlisle et al., 2009). According to our data, the region is part of the Spring migration route, but not, or less so, of the Autumn route.

Birds assemble differently in response to habitat characteristics (Wiens & Rotenberry, 1981), although bird-habitat relationships are complex (Strong & Bock, 1990). In our study, habitat characteristics were part of the best model in 78% of the cases (Tables 5-7). Three habitat variables more consistently affected bird assemblages and species. The first was that the averaged minimum and maximum height of shrubs and trees influenced birds positively, which conforms with general known principles in bird ecology (Brand et al., 2008; MacArthur & MacArthur, 1961; Merrit & Bateman, 2012; Rockwell & Stephen, 2018), and with findings in other xeroriparian systems (Brand et al., 2008). The second was that closed canopies had a negative effect. Closed canopies have been found to influence birds negatively by reducing light at ground level resulting in a less developed herb and shrub community (Beedy, 1981). The third case was that herb vertical density at 25-75 cm had also a negative effect. But this is a spurious outcome that resulted from the dense herb layer at the beginning of the study (Fig. 8), when bird abundance variables were lower, while the circannual process of herbs drying and decaying in the late Autumn and early Winter causes low herb cover coinciding with the increase in bird abundance (Figs. 2, 3).

The bird assemblages of the xeroriparian systems studied not only were different from each other, but also varied internally, between sections (Figs. 6, 7). The arrangement of the 9 sections according to their species presence/absence in axis 1, explaining 33% of the variance, follows a clear gradient (Fig. 7 top). On the left side are sections with steep, narrow, and rocky ravines with large boulders, dominated by oaks and junipers that form a close canopy with little understory herbaceous vegetation. On the right, wide and open pebbled washes, dominated by a more heterogeneous tree community composed of peppertrees, arborescent nopales, and huisaches, with a well-developed herbaceous layer. The bird communities responded to this gradient with increasing richness and abundance from left to right.

In the same graph, axis 2 follows a gradient from a well-developed shrub community and abundant litter and wetter soil to no or scarce shrubs with a dense herbaceous layer and drier ground. This gradient apparently drives the food resources available to birds, as suggested by the preponderant bird guilds in the different sections (Fig. 6): insects in its lower end to seeds in the upper end. Overall, La Colorada with the most heterogeneous sections, vegetation-wise, had also the richest bird assemblage, while La Laborcilla, with the most homogenous sections, had the poorest one, with Rancho Santoyo intermediate in both attributes (Table 4; Fig. 6; Supplementary material 5). Using bird abundance instead of binary information rearranged the PCA graph layout (Fig. 7 lower) because of the effect of species that were widespread and abundant, but without losing a resemblance to the species presence/absence PCA.

Vertical structure is important for birds, but floristic composition can also influence their diversity (Fleishman et al., 2003; Rotenberry, 1985). For example, oaks are of little attraction to most birds (Powell & Steidl, 2015), and their dominance at La Laborcilla and the upper section of La Colorada coincided with the lower richness and abundance of their bird assemblages (Fig. 6; Supplementary material 2). Rancho Santoyo supported more xeroriparian-dependent individuals, mostly of Setophaga coronata and Corthylio calendula, both small insectivorous birds. The middle and upper sections where these 2 species thrived had large cottonwoods (Populus fremontii) and willows (Salix bonplandiana). In contrast, in the middle section of La Colorada, which also had tall trees but were peppertrees and arborescent nopales, these 2 bird species were much less abundant.

Each of the systems studied had a distinct signature given by one species or dominant bird guild(s), although such signature was largely due to the assemblages in the individual sections (Fig. 6). The signature species at Laborcilla was Aphelocoma woodhouseii, whose primary habitat includes oak and juniper forests, where it typically feeds on juniper berries in the Autumn and Winter (Fig. 5; Cornell Lab of Ornithology, 2019). Although the upper Colorada section grouped with La Laborcilla, with which it shared oaks, lacked junipers and was not used by Aphelocoma woodhouseii. Their close PCA grouping rather resulted from their shared poor bird assemblages. Rancho Santoyo can be identified with migrant insectivorous birds and La Colorada with migrant granivorous birds, in concordance with the explanation on the PCA arrangement provided above.

The lower proportion and abundance of migratory insectivorous birds and absence of granivorous birds at La Laborcilla might have been caused by its less developed understory vegetation and enclosed canyon conditions. In contrast, Rancho Santoyo´s upper and middle section provided the best habitat for insectivore migrants. This system was exuberant in herb and shrub foliage, likely as a result of the longer presence of ground humidity, but had also plenty of sunny spots; and the system bordered open rangeland, providing lengthy, sharp borders, especially in its upper and middle sections. Granivore migrants were a small component of the communities we documented, and they were present almost exclusively in La Colorada´s middle section. This site had an open canopy and combined taller shrubs with denser and taller herbs than in the other sections of the same and the 2 other systems, providing higher habitat heterogeneity and, likely, more seeds. A more developed herb-shrub stratum at 0-75 cm at La Colorada than at other sites provided good escape cover adjacent to open patches that provided seeds (Table 4; Supplementary material 4).

As our data exhibit, habitats associated with non-perennial xeroriparian streams are far from uniform, not only between systems but also within them. At a landscape level they are clearly keystone structures, at least for the birds but surely for other groups as well, both collectively and individually. The 3 systems studied by us cover about 55 ha, roughly 0.1% of the area in which they occur. However, they supported 20% of the potential species of terrestrial birds of the region, including 15 that we have recorded only in such riparian habitat. Our data exhibit that in addition to their importance for resident species, some ephemeral and intermittent xeroriparian habitat in the southern part of the Mexican Altiplano are important for northbound Spring migrating birds.

Our study is a first approximation to the ecological role of xeroriparian systems in the region. However, many issues, like their importance as nesting habitat, provision of food, climatic protection, interaction with adjacent and farther away habitats, among others, remain to be studied. Nevertheless, if these xeroriparian habitats disappear, regional biodiversity would be impacted. Not only 1 or a few, but many or all xeroriparian systems, and their different sections in the region studied by us should be targeted for conservation management. Xeroriparian systems have long been considered important elements of the landscape and their conservation needs recognized. However, such consideration, and the actions derived from it, usually focus on perennial streams with their lush arboreal communities. This focus is biased and excludes an important part of xeroriparian habitat: that created by ephemeral and intermittent streams. Despite their low consideration in research and in conservation agendas, as our study and a few others have demonstrated, ephemeral and intermittent xeroriparian habitat can play a crucial role in arid and semiarid lands (Johnson & Haight, 1985; Levick et al., 2008; Sánchez-Montoya et al., 2017; Szaro & Jakle, 1985). Despite covering less than 0.1% of the region´s area, in our study they supported 20% of all terrestrial species that we documented in the region (Mellink et al., 2016, 2017; Riojas-López & Mellink, 2019; Riojas-López et al., 2019), while those that we documented only in xeroriparian systems account for 9% of all species documented. A scenario of ecological importance of non-perennial xeroriparian systems and research and management neglect are likely to occur in many other arid and semiarid regions of the world. Hence, it might be time to join forces and impulse a global agenda for their conservation, which is now especially pertinent in view of the ongoing climate change in which drier and hotter regimes are predicted.

Acknowledgements

Jaime Luévano Esparza, David H. Almanzor, Santiago Cortés, and Marco A. Carrasco assisted during field work. Access and research permission were granted kindly by owners Family Santoyo (Rancho Santoyo) and Enrique Campos (La Laborcilla), and ranch manager Melquíades Contreras (La Colorada). Ezequiel Martínez and Margarita Chávez provided logistic support. Two anonymous reviewers provided extensive and valuable comments. Our greatest appreciation to all of them. Financial support was provided by the Centro de Investigación Científica y de Educación Superior de Ensenada (CICESE), the Universidad de Guadalajara, and the first two authors´ personal funds. The Consejo Nacional de Humanidades, Ciencias y Tecnologías supported MM-O through a M.Sc. scholarship.

References

Arizmendi, M. D., Dávila, P., Estrada, A., Figueroa, E., Márquez-Valdelamar, L., Lira, R. et al. (2008). Riparian mesquite bushes are important for bird conservation in tropical arid Mexico. Journal of Arid Environments, 72,1146–1163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaridenv.2007.12.017

Beedy, E. C. (1981). Bird communities and forest structure in the Sierra Nevada of California. Condor, 83,97–105. https://doi.org/10.2307/1367415

Brand, L. A., White, G. C., & Noon, B. R. (2008). Factors influencing species richness and community composition of breeding birds in a desert riparian corridor. Condor, 110,199–210. https://doi.org/10.1525/cond.2008.8421

Burnham, K. P., & Anderson, D. R. (2002). Model selection and multimodel inference: A practical information-theoretic approach. 2nd Ed. New York: Springer-Verlag.

Carlisle, J. D., Skagen, S. K., Kus, B. E., Van Riper III, C., Paxtons, K. L., & Kelly, J. F. (2009). Landbird migration in the American West: recent progress and future research directions. Condor, 111,211–225. https://doi.org/10.1525/cond.2009.080096

Challenger, A. (1998). Utilización y conservación de los ecosistemas terrestres de México. México D.F.: Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad, Instituto de Biología (UNAM), and Agrupación Sierra Madre.

Chesser, R. T., Billerman, S. M., Burns, K. J., Cicero, C., J. L. Dunn, J. L., Hernández-Baños, B. E. et al. (2023). Check-list of North American Birds (online). American Ornithological Society. Retrieved on March 14th, 2024 from: https://checklist.americanornithology.org/taxa/

Conabio (Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad). (1998). La diversidad biológica de México: estudio de país. México D.F.: Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad.

Conabio (Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad). (2008). Capital natural de México, vol. I: Conocimiento actual de la biodiversidad. México D.F.: Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology (2019). Woodhouse´s Scrub-Jay. Retrieved on June 7th, 2023 from: https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Woodhouses_Scrub-Jay/lifehistory#

Datry, T., Bonada, N., & Boulton, A. J. (2017). Conclusions: recent advances and future prospects in the ecology and management of intermittent rivers and ephemeral streams. In T. Datry, N. Bonada, & A. J. Boulton (Eds.), Intermittent rivers and ephemeral streams: ecology and management (pp. 563–584). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Dunning, J. B., Danielson, B. J., & Pulliam, H. R. (1992). Ecological processes that affect populations in complex landscapes. Oikos, 65,169–175. https://doi.org/10.2307/3544901

Fleishman, E., McDonal, N., Nally, R. M., Murphy, D. D., Walters, J., & Floyd, T. (2003). Effects of floristics, physiognomy and non-native vegetation on riparian bird communities in a Mojave Desert watershed. Journal of Animal Ecology, 72, 484–490. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2656.2003.00718.x

Harker, M., García R., L. A., & Riojas-López, M. E. (2008). Composición florística de cuatro hábitats en el rancho Las Papas de Arriba, municipio de Ojuelos de Jalisco, Jalisco, México. Acta Botanica Mexicana, 85,1–29.

Hays, R. L., Summers, C., & Seitz, W. L. (1981). Estimating wildlife habitat variables. Washington DC: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Hinojosa-Huerta, O., Soto-Montoya, E., Gómez-Sapiens, M., Calvo-Fonseca, A., Guzmán-Olachea, R., Butrón-Méndez, J. et al. (2013). The birds of the Ciénega de Santa Clara, a wetland of international importance within the Colorado River delta. Ecological Engineering, 59,61–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2013.03.005

Johnson, R. R., & Haight, L. T. (1985). Avian use of xeroriparian ecosystems in the North American warm deserts. In R. R. Johnson, C. D. Ziebell, D. R. Patton, P. F. Ffolliott, P. F., & R. H. Hamre (Tech. Coords.), Riparian ecosystems and their management: reconciling conflicting uses (pp. 156–160). General Technical Report RM-GTR-120. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station.

Kirkpatrick, C., Conway, C., & LaRoche, D. (2009). Surface water depletion and riparian birds. Tucson, Arizona: Arizona Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit.

Knopf, F. L. (1985). Significance of riparian vegetation to breeding birds across an altitudinal cline. In R. R. Johnson, C. D. Ziebell, D. R. Patton, P. F. Ffolliott, & R. H. Hamre (Tech. Coords.), Riparian ecosystems and their management: reconciling conflicting uses (pp. 105–111). General Technical Report RM-GTR-120. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station.

Knopf, F. L., Johnson, R. R., Rich, T., Samson, F. B., & Szaro, R. C., 1988. Conservation of riparian ecosystems in the United States. Wilson Bulletin, 100,272–284. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4162566

Krueper, D. J. (1993). Effects of land use practices on western riparian ecosystems. In D. M. Finch, & P. W. Stangel (Eds.), Status and management of neotropical migratory birds (pp. 321–330). General Technical Report RM-229. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station.

Krueper, D. J. (1996). Effects of livestock management on southwestern riparian ecosystems. In D. W. Shaw, & D. M. Finch (Tec. Coords.), Desired future conditions for Southwestern riparian ecosystems: bringing interests and concerns together (pp. 281–301). General Technical Report RM-GTR-272. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station.

Krueper, D. J. (2000). Conservation priorities in naturally fragmented and human-altered riparian habitats of the arid West. In R. Bonney, D. N. Pachley, R. J. Cooper, & L. Nioes (Eds.), Strategies for bird conservation: the partners in flight planning process (pp. 88–90). USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-16. Ogden, Utah, U.S.A.: Rocky Mountain Research Station.

Levick, L., Fonseca, J, Goodrich, D., Hernández, M., Semmens, D., Stromberg, J. et al. (2008). The ecological and hydrological significance of ephemeral and intermittent streams in the arid and semi-arid American southwest. Washington D.C.: Office of Research and Development, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

MacArthur R. H., & MacArthur, J. W. (1961). On bird species diversity. Ecology, 423,594–598. https://doi.org/10.2307/1932254

McDonough, O. T., Hosen, J. D., & Palmer, M. A. (2011). Temporary streams: the hydrology, geography, and ecology of non-perennially flowing waters. In H. S. Elliot, & L. E. Martin (Eds.), River ecosystems: dynamics, management and conservation (pp. 259–289). Hauppauge, N.Y.: Nova Science.

Mellink, E., & Riojas-López, M. E. (2020). Livestock and grassland interrelationship along five centuries of ranching the semiarid grasslands on the southern highlands of the Mexican Altiplano. Elementa Science of the Anthropocene, 8, 20. https://doi.org/10.1525/elementa.416

Mellink, E., Riojas-López, M. E., & Giraudoux, P. (2016). A neglected opportunity for bird conservation: the value of a perennial, semiarid agroecosystem in the Llanos de Ojuelos, central Mexico. Journal of Arid Environments, 124,1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaridenv.2015.07.005

Mellink E., Riojas-López, M. E., & Cárdenas-García, M. (2017). Biodiversity conservation in an anthropized landscape: Trees, not patch size drive bird community composition in a low-input agroecosystem. Plos One, 12, e0179438. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0179438

Merritt, D. M., & Bateman, H. L. (2012). Linking stream flow and groundwater to avian habitat in a desert riparian system. Ecological Applications, 22, 1973–1988. https://doi.org/10.1890/12-0303.1

Neate-Clegg, M. H. C., Horns, J. J., Buchert, M., Pope, T. L., Norvell, R., Parrish, J. R. et al. (2021). The effects of climate change and fluctuations on the riparian bird communities of the arid Intermountain West. Animal Conservation, 25,325–341. https://doi.org/10.1111/acv.12755

Nieto-Samaniego, Á. F., Alaniz-Ávarez, S. A., & Camprubí, A. (2005). La Mesa Central de México: estratigrafía, estructura y evolución tectónica cenozoica. Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana, 57, 285–318. https://doi.org/10.18268/bsgm2005v57n3a3

Partners in Flight Databases. (2023). Retrieved on July 13th,

2023 from: https://pif.birdconservancy.org/avian-conserva

tion-assessment-database-scores/

Patten, D. T., Carothers, S. W., Johnson, R. R., & Hamre, R. H. (2018). Development of the science of riparian ecology in the semi-arid western United States. In R. R. Johnson, S. W. Carothers, D. M. Finch, K. J. Kingsley, & J. T. Stanley (Tech. Eds.), Riparian research and management: past, present, future, Volume 1 (pp. 1–16). General Technical Report RM-GTR-373. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station.

Pérez-Amezola, M. C., Gatica-Colima, A. B. M. Cuevas-Ortalejo, D. M., Martínez-Calderas, J. M., & Vital-García, C. (2020). Riparian biota of the Protected Area of Flora and Fauna Santa Elena canyon, Mexico. Revista Bio Ciencias, 7, e798. https://doi.org/10.15741/revbio.07.e798

Powell, B. F., & Steidl, R. J. (2015). Influence of vegetation on montane riparian bird communities in the sky islands of Arizona, USA. Southwestern Naturalist 60,65–71. https://doi.org/10.1894/MCG-09.1

Riojas-López, M. E., & Mellink, E. (2019). Registros relevantes de aves en el sur del Altiplano Mexicano. Huitzil, 20, e-513. https://doi.org/10.28947/hrmo.2019.20.2.457

Riojas-López, M. E., Mellink, E., & Almanzor-Rojas, D.H. (2019). Estado del conocimiento de los carnívoros nativos (Mammalia) en un paisaje antropizado del Altiplano Mexi-

cano: el caso de Los Llanos de Ojuelos. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 90,e902669. https://doi.org/10.22201/ib.

20078706e.2019.90.2669

Riparian Habitat Joint Venture (2004). The riparian bird conser-

vation plan: a strategy for reversing the decline of riparian associated birds in California. Ver. 2.0. Retrieved on September

28th, 2021 from: https://web.archive.org/web/2018072200

1457id_/http://www.prbo.org/calpif/pdfs/riparian_v-2.pdf

Rockwell, S. M., & Stephens, J. L. (2018). Habitat selection of riparian birds at restoration sites along the Trinity River, California. Restoration Ecology, 26,767–777. https://doi.org/10.1111/rec.12624

Rosenberg, K. V, Dokter, A. M., Blancher, P. J., Sauer, J. R., Smith, A. C., Smith, P. A. et al. (2019). Decline of the North American avifauna. Science, 366,120–124. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaw1313

Rosgen, D. A. (1994). A classification of natural rivers. Catena, 22,169–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/0341-8162(94)90001-9

Rotenberry, J. T. (1985). The role of habitat in avian community composition: physiognomy or floristics? Oecologia, 67,213– 217. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00384286

Sánchez-Montoya, M. M., Moleón, M., Sánchez-Zapata, J.A., & Escoriza, D. (2017). The biota of intermittent and ephemeral rivers: amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals. In T. Datry, N. Bonada, & A. J. Boulton (Eds.), Intermittent rivers and ephemeral streams: ecology and management (pp. 299–322). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Şekercioǧlu, C. H., Loarie, S. R., Oviedo-Brenes, F., Mendenhall, C. D., Daily, G. C., & Ehrlich, P. R. (2015). Tropical countryside riparian corridors provide critical habitat and connectivity for seed-dispersing forest birds in a fragmented landscape. Journal of Ornithology, 156,343–353. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-015-1299-x

Semarnat (Secretaría del Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales). (2010). Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010, Protección ambiental – Especies nativas de México de flora y fauna silvestres – Categorías de riesgo y especificaciones para su inclusión, exclusión o cambio – Lista de especies en riesgo. Diario Oficial de la Federación. 30 de diciembre de 2010, Segunda Sección, México.

Seymour, C. L., & Simmons, R. E. (2008). Can severely fragmented patches of riparian vegetation still be important for arid-land bird diversity? Journal of Arid Environments, 72,2275–2281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaridenv.2008.07.014

Skagen, S. K., Melcher, C. P., Howe, W. H., & Knopf, F. L. (1998). Comparative use of riparian corridors and oases by migrating birds in southeast Arizona. Conservation Biology, 12,896–909. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.1998.96384.x

Strong, T. R., & Bock, C. E. (1990). Bird species distribution patterns in riparian habitats in southeastern Arizona. Condor, 92,866–885. https://doi.org/10.2307/1368723

Szaro, R. C., & Jakle, M. D. (1985). Avian use of a desert riparian island and its adjacent scrub habitat. Condor, 87,511–519. https://doi.org/10.2307/1367948

Wiens, J. A., & Rotenberry, J. T. (1981). Habitat associations and community structure of birds in shrubsteppe environments. Ecological Monographs, 51,21–41. https://doi.org/10.2307/

2937305