Conociendo lo que se conoce: biología, distribución e idoneidad de hábitat del escarabajo barbudo Rhinostomus barbirostris (Curculionidae: Dryophthorinae) en México

Osiris Valerio-Mendoza a, b, Leticia Soriano-Flores c, Idalia Fabiola Lazaro-Lopez f, Miguel Murguía-Romero d, Enrique Ortiz e, Gerardo Cuellar-Rodrigueza, Francisco Armendáriz-Toledano b, *

a Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, Facultad de Ciencias Forestales, Campus Linares, Km 145, Nacional 85, 67700 Linares, Nuevo León, Mexico

b Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Biología, Departamento de Zoología, Colección Nacional de Insectos, Tercer Circuito s/n, Ciudad Universitaria, 04510 Ciudad de México, Mexico

c Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo, Montes Urales No. 440, Lomas de Chapultepec, 11000 Ciudad de México, Mexico

d Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Biología, Unidad de Informática para la Biodiversidad, Tercer Circuito s/n, Ciudad Universitaria, 04510 Ciudad de México, Mexico

e Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Biología, Departamento de Botánica, Tercer Circuito s/n, Ciudad Universitaria, 04510 Ciudad de México, Mexico

f Alianza de Comunidades Chocho-Mixtecas del Estado de Oaxaca, Cedros s/n, Col. Emiliano Zapata, Asunción Nochixtlán Oaxaca, Mexico

*Autor para correspondencia: farmendariztoledano@ib.unam.mx (F. Armendáriz-Toledano)

Recibido: 27 marzo 2025; aceptado: 24 septiembre 2025

Abstract

The bearded weevil, Rhinostomus barbirostris, is a significant damaging organism of palms in the Neotropics, heavily impacting ecologically and economically important species. This study details its biology, distribution, and habitat suitability in Mexico, focusing on a recent outbreak in the Tehuacán-Cuicatlán Biosphere Reserve (TCBR), where it affected the sweet palm, Brahea dulcis. Field surveys confirmed significant damage and palm death in the TCBR due to weevil larvae and adults. A database of historical and current records was used to model its potential distribution using bioclimatic variables. Results show wide habitat suitability for R. barbirostris across Mexico, especially in humid montane and tropical forests, although recent records center on the TCBR. This research provided crucial data on the weevil’s biology and distribution, emphasizing the need for monitoring and management to protect native palm populations and prevent economic and ecological harm.

Keywords: Phytofagous pests; Neotropical palms; Brahea dulcis

Resumen

El gorgojo barbudo, Rhinostomus barbirostris, es un organismo dañino para las palmas en el Neotrópico, con un fuerte impacto en especies de importancia ecológica y económica. Este estudio detalla su biología, distribución e idoneidad de hábitat en México, centrándose en un brote reciente en la Reserva de la Biosfera Tehuacán-Cuicatlán (RBTC), donde afectó a la palma dulce, Brahea dulcis. Los estudios de campo confirmaron daños significativos y la muerte de palmas en la RBTC debido a larvas y adultos del gorgojo. Se utilizó una base de datos de registros históricos y actuales para modelar su distribución potencial mediante variables bioclimáticas. Los resultados muestran una amplia idoneidad de hábitat para R. barbirostris en todo México, especialmente en bosques húmedos de montaña y tropicales, aunque los registros recientes se centran en la RBTC. Esta investigación proporcionó datos cruciales sobre la biología y distribución del gorgojo, enfatizando la necesidad de monitoreo y manejo para proteger las poblaciones nativas de palmas y prevenir daños económicos y ecológicos.

Palabras clave: Plagas fitófagas; Palmas neotropicales; Brahea dulcis

Introduction

Dryophthorinae, identified by Schoenherr (1825), is recognized as one of the most distinctive and well-defined subfamilies of Curculionidae, notable for its unique synapomorphies (Kuschel, 1995; Luna-Cozar et al., 2024; Marvaldi & Morrone, 2000). These weevils, among the largest of the family, present a great diversity, with around 1,200 species grouped in more than 150 genera and 5 main tribes: Dryophthorinini, Stromboscerini, Cryptodermatini, Orthognathini and Rhynchophorini (Oberprieler et al., 2007).

This group of insects stands out for its specialization in feeding monocotyledons, and to a lesser extent, on dicotyledons. Their saprophagous habits, mainly focused on leaf litter and wood (Anderson & Marvaldi, 2014; Gardner, 1934, 1938; Grebennikov, 2018a-c; Vaurie, 1970a, b, 1971), allow them to adapt to a wide variety of ecosystems, from tropical forests to deserts and grasslands, on all continents. Their evolutionary success, evidenced by an extensive fossil record (McKenna et al., 2015; Chamorro et al., 2021) dating back between 65 and 115 million years, suggests great adaptability and a close relationship with the evolution of plants (O’Meara, 2001; McKenna et al., 2009).

Many species of the subfamily represent a serious threat to agriculture worldwide, because they feed on a wide range of crops, both tropical and temperate, including palms, pineapple, bamboo, banana, sugarcane, maize, wheat and rice (Van Huis et al., 2013). Among the most prominent and damaging members are the rice weevils of the genus Sitophilus, Schoenherr, and the palm weevils of the genera Rhynchophorus, Herbst, and Rhinostomus Rafinesque. These taxa cause significant economic losses and put food security at risk in numerous regions of the world (Rugman-Jones et al., 2013; Van Huis et al., 2013).

Rhinostomus Rafinesque, 1815 has 7 species: R. barbirostris, R. oblitus, R. quadrisignatus, R. scrutator, R. thompsoni from the Neotropics; R. niger from the Afrotropical region; and the Oriental R. meldolae (Vaurie, 1970a). The bearded weevil R. barbirostris is considered the third largest weevil on the planet, being surpassed in the same subfamily by Protocerius collosus from Australasia (60 mm) and Rhynchodynamis filirostris (Vaurie, 1970a; Zaragoza-Caballero et al., 2015). Adult individuals are characterized by having an average length of 2-4 cm. Males present an interesting appearance with a “brush of hairs” or setae on the head, that represent an advantage during courtship when they are rubbed on the dorsal surface of the female (Eberhard, 1983). Females lack a brush and prefer to oviposit on the intact bark of weakened or stressed palms (Cocos nucifera), both cultivated and wild (Bouchard, 2014; FAO, 2013; Zaragoza-Caballero et al., 2015). The bearded weevil is an important pest of palm trees across its distribution range, feeding on Attalea funifera Burret, A. maripa (Aubl.) Mart., A. pindobassu Bondar, A. piassabossu Bondar, Bactris gasipaes Kunth, Brahea dulcis (Kunth) Mart., Cocos botryophora Mart., C. coronata Mart, C. nucifera L., Elaeis guineensis Jacq., Euterpe oleracea Mart., Mauritia flexuosa L. F., Oenocarpa bacaba Mart., and Syagrus romanzoffiana (Cham.) Glassman (Araujo et al., 2018; Choo et al., 2009; Conafor, 2020; Conanp, 2015; De la Pava et al., 2019; Eberhard, 1983; Franqui-Rivera et al., 2003; Van Itterbeeck & Van-Huis, 2012; Lanteri et al., 2002; Pardo-Locamo et al., 2005, 2019; Salas, 1980; Vargas et al., 2013; Vaurie, 1970a; Vergara-Navarro et al., 2021; Zaragoza-Caballero et al., 2015). Like other dryophtorines, R. barbirostris shows a marked preference for plants in a state of stress, weakened or dead. These adverse conditions, commonly associated with intensive agricultural practices such as prolonged drought, monodominance, and the presence of diseases, create an environment conducive to the development of this weevil (Anderson & Marvaldi, 2014; Oberprieler et al., 2007; Zimmerman, 1968a, b, 1993). Its distribution includes humid climates from central Mexico, Central America, Venezuela, Ecuador, Guyana, Brazil, Peru, Suriname, Uruguay, and Argentina (Pardo-Locardo et al., 2019; Zaragoza-Caballero et al., 2015).

Rhinostomus barbirostris is distributed in approximately one-third of the Mexican territory (Campeche, Chiapas, Guerrero, Jalisco, Nayarit, Oaxaca, Puebla, Tabasco, Quintana Roo, Veracruz, and Yucatán), and there are few records of damage and affectation by this beetle (Conafor, 2020). Basic aspects of biology, distribution, strategies, and control measures in R. barbirostris have not yet been addressed in Mexico; therefore, the potential damage to palm populations in the territory is unknown. In Central and South America, the damage caused to palms has led to establishing control methods, the most practiced is the early removal of infested plants, in addition to treating them with insecticides and destroying them once the disease is diagnosed (Franqui-Rivera & Medina-Gaud, 2003). Recently, in Oaxaca (2020) and Puebla (2015) records of the bearded weevil in the sweet palm Brahea dulcis have been reported in communities of the Tehuacán-Cuicatlán Biosphere Reserve. The sweet palmnative to Mexico and Central America is distinguished by its solitary stem, large leaves, and glaucous green color(Pavón et al., 2006; Rzedowski, 2006; SINAT & Semarnat, 2009). It lives in dry and semi-arid areas, mainly on limestone soils. It is found in a wide geographic region, from northern Veracruz to Central America, inhabiting diverse ecosystems such as dry forests, scrubland and oak forests (Quero, 1994). The main threat to the survival of this species is human activity. The unsustainable extraction of leaves for artisanal and construction purposes, together with extensive habitat degradation caused by agricultural expansion, livestock grazing, and urban development, has resulted in a pronounced reduction of its populations (Rangel-Landa et al., 2014; Rzedowski, 2006). In Mexico, the use of “Mexican sweet palm” is regulated by various laws and regulations, such as the General Wildlife Law and NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2001, which categorize species and establish protection measures (López-Serrano et al., 2021; Semarnat, 1997, 2002).

Given the limited information available, this study aimed to characterize the damage to the green palm (B. dulcis) and determine the incidence caused by R. barbirostris within the Tehuacán-Cuicatlán Biosphere Reserve to enhance understanding and management of this weevil in Mexico. From field surveys, we generated basic descriptive information about its biology and interaction with this plant. Likewise, we analyzed the temporal and spatial distribution of the weevil based on historical records of specimens deposited in entomological collections and online databases from Mexico. The gathered information will enhance the understanding of biological and behavioral variation, summarize the weevil’s distribution pattern, offer insights into its interactions, and help identify both sampled areas and potential monitoring sites.

Materials and methods

The Tehuacán-Cuicatlán Biosphere Reserve (TCBR) is located in southeastern Puebla and northwestern Oaxaca, it is the arid region with the greatest biodiversity in North America and 1 of the places with the greatest presence of cacti, flora, and fauna (Conanp, 2013; Conafor, 2023; Sinco-Ramos et al., 2021). With just over 4,900 km2, the Reserve is populated by the densest forests of columnar cacti with 45 of the 70 known species in the world (Pérez-Irineo & Mandujano-Rodríguez, 2020).

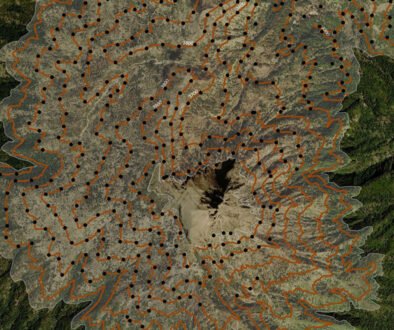

In February 2022, the Chochonteca zone of the Cañada Region covering Santa María Almoloyas, San Juan Tonaltepec, San Pedro Nodon, San Pedro Jocotipac, San Pedro Jaltepetongo, Santa María Ixcatlán, Santa María Cotahiuxtla, and Santiago Nacaltepec within the TCBR was visited. Agricultural areas were also surveyed due to the presence of the bearded weevil (R. barbirostris), which was observed to be affecting wild specimens of the green palm (B. dulcis), causing damage to their development and even threatening their survival. Guided tours were conducted by communal landholders, during which damage to the host plant was documented through photographs and field reports. Additionally, live specimens at various developmental stages were collected for analysis and taxonomic identification at the Collection Nacional de Insectos, Instituto de Biología, UNAM (CNIN-UNAM). Morphological identification of adults was carried out using the keys of Vaurie (1970a), based on the external morphological characters of the eyes, pronotum, antennal scape, and the sculpture of the tibia and femur. Identification was complemented with the additional morphological criteria of Morrone and Cuevas (2002). Photographs of specimens were taken with a Digital Rising Cam 16 MP attached to a RisingTech UrCMOS stereoscope.

To characterize the palms and quantify the degree of infestation, we conducted transects in the damaged areas. Affected palms were identified and documented with field notes and photographs. For each infested palm, we determined the following variables to assess the characteristics of the damage caused by R. barbirostris: height of the perforations on the trunk (HP), diameter of the perforations observed (DOP), and number of perforations present in 10 cm2 (NP).

The historical, current, and potential distribution of R. barbirostris were determined using data obtained from various databases. Records were consulted and downloaded from the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF 2023), iNaturalist (2023). The specimens examined in this study were obtained from the following collections: AMNH (American Museum of Natural History, New York, USA.), ASU (Arizona State University, Charles W. O’Brien Collection), CEAM (Centro de Entomología y Acarologia, Instituto de Fitosanidad, Colegio de Postgraduados, Montecillos), CECR (Centro de Referencia, SENASICA-SAGARPA), Conafor (Comisión Nacional Forestal, México), CNIN-UNAM (Colección Nacional de Insectos, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México), DGSV (Dirección General de Sanidad Vegetal, SENASICA), ECOSUR (El Colegio de la Frontera Sur, Colección Entomológica San Cristóbal y Tapachula, Chiapas, México), MZFC (Museo de Zoología, Facultad de Ciencias, UNAM, Mexico), and UACH (Universidad Autónoma Chapingo, Colección del Departamento Forestal).

In total, 506 records were obtained, from which the following information was summarized: total registers with geographic coordinates, year range, collections, with maximum registers, countries, latitude range, longitude range, main collector, and main identifiers. All records were included in a database; records without geographic coordinates were geopositioned with Google Earth (2020). To determine the feeding spectrum of R. barbirostris, a table of the registered hosts was prepared and graphed according to the number of reports per host and species.

The potential distribution model for R. barbirostris was based on 655 georeferenced occurrence records. This final dataset is the result of a rigorous preprocessing process that ensured quality by eliminating errors and duplicates (Guisan & Zimmermann, 2000; Sillero, 2011; Warren, 2012). The records cover the entire known range of the species in Mexico, Central America, and South America and were the input data for Wallace package (Carretero & Sillero, 2016; Kass et al., 2023).

A database was compiled with presence records covering the entire range of the species. This strategy was adopted because niche models are highly sensitive to the spatial distribution of data. Using subsets of the range can violate key assumptions, such as equilibrium with the environment and niche homogeneity, potentially generating biased results. Therefore, including all available records ensures a more complete and robust representation of the species’ ecological niche. For the record, the values of the 19 bioclimatic variables of WorldClim 2 were considered (Fick & Hijmans, 2017). Extraction was done in QGIS 3.36.3 using the Point sampling tool plugin (https://github.com/borysiasty/pointsamplingtool). After the extraction, a multivariate normality test was performed on the values of the variables with the R package mvn (Korkmaz et al., 2014), which was negative. The distribution of environmental variables was examined to understand the species’ ecological niche. A normal distribution would suggest that the species has a narrow preference for certain conditions, while a non-normal distribution indicates that it can tolerate a wider range of environments. Since our species’ variables do not follow a normal distribution, it was decided to model the entire species distribution rather than a fraction of it. This decision avoids a bias in the model that could underestimate its adaptive capacity to a wider range of environmental conditions (Brown, 1984).

To evaluate the correlation among variables, a Spearman correlation analysis were performed using the R core function. Using the Wallace interface, next, the parameters specified are described (Kass et al., 2023). Those variables with a correlation value less than 0.85 were selected. Thus, the selected variables were: Bio01, Bio02, Bio03, Bio04, Bio05, Bio06, Bio08, Bio12, Bio14, Bio18, which were used to build the model at a resolution of 5 arcmin (~ 20km). The model calibration area (M) comprised Mexico, Central America, and South America, which includes all records of R. barbirostris. Records were thinned to 55.55 km, reducing the records to 220 (Aiello-Lammens et al., 2015; Boria et al., 2014).

A background of 5,000 points was generated. The selection of the number of background points was based on the common MaxEnt practice, which sets 10,000 points by default. Although there is no consensus on the optimal number, recent literature indicates that this value is an adequate baseline, depending on the study area and the resolution of the variables (Merow et al., 2013; Phillips et al., 2017). It is recognized that an excessive number of points can artificially inflate the AUC value (Sofaer et al., 2019); however, evaluating an optimal number of background points through metrics such as the Boyce index or True Skill Statistics (Valavi et al., 2022) is beyond the scope of this study. Therefore, the default value of 10,000 points was chosen as a justified balance between study area coverage and computational feasibility.

For model validation, a non-spatial Jackknife partition was used, applying the Maxent algorithm with a linear response (Elith et al., 2011; Phillips et al., 2006). This data partition was selected for model evaluation due to the small sample size (Shcheglovitova & Anderson, 2013). Three models were generated with a regularization multiplier (1, 1.5, and 2). The model with the highest AUC was selected (with a regularization multiplier of 1), whose value of 0.73 is considered acceptable. The “Minimum Training Presence” was used to generate the binary map. The map was exported to a TIFF file and imported to QGIS (QGIS.org, 2024) to calculate the percentage of area of the model in each of the 32 federal entities of Mexico.

In addition to the calculation by state, an analysis was conducted to determine how the potential distribution of R. barbirostris is distributed across the biomes of the national territory. Using the biome layer, a binary map of the species’ potential distribution was overlaid. Subsequently, the total area (km2) and the percentage of area projected by the model for each biome were quantified, allowing for a deeper understanding of the species’ preference for certain types of ecosystems.

Results

Rhinostomus barbirostris specimens collected in the Tehuacán-Cuicatlán Biosphere Reserve were found associated with deteriorated B. dulcis palms. Species identifications were confirmed by the presence of a slightly raised frontal keel between the eyes (Fig. 1a-b), front femur virtually impunctate, front tibia on inner edge with long teeth; front tibia of male without hairs (Fig. 1c-e). Adults were collected with the respective larvae and pupae. The presence of R. barbirostris was recorded in wild populations of B. dulcis in Santa María Almoloyas, San Juan Tonaltepec, San Pedro Nodón, San Pedro Jaltepetongo, Santa María Ixcatlán, Santa María Cotahuixtla, and Santiago Nacaltepec, Oaxaca, Mexico. In addition to these sites, surveys were conducted in other agricultural centers such as San Pedro Jaltepetongo and San Pedro Jocotipac, where the presence of R. barbirostris was also documented.

In all colonized palms, the beetles caused notable damage to the base of stems and foliage, which disrupted their growth and, in some cases, led to the death of the affected specimens. The palm damage can be observed in individual or gregarious palms. In the gregarious stems, some of the palms display healthy foliage, meanwhile others exhibit signs of deterioration, such as browning and wilting leaves, indicating early damage from the insect infestation (Fig. 2a-c). In individual palms, the lateral shoots that grow on the main stem of the palm trees also presented these symptoms (Fig. 2d). The affected specimens showed the foliage dry and drooping, with the leaves appearing dead and lifeless. In the gregarious spots, it is evident that the damage is progressive, affecting the palms around the infested 1 (Fig. 2b). In the palms completely succumbed to the infestation, the stem is visibly blackened and decayed, standing as a stark remnant of the once-living tree, showing the lethal impact of the weevil. These palms are dry, and the foliage has collapsed (Fig. 2d). A close-up of the palm trunk revealed multiple boreholes and resin exudation; the damage is severe, with the bark visibly compromised by larval activity, showing extensive boring damage (Fig. 2e-f, 3d-f). The holes are located in the ground near the base of the stipe at the average height of 1.35 m, the holes secrete brown resin, with the smell of fermented tissue (Fig. 3b-c)

A single, distinct borehole in the trunk is created by an adult weevil for laying eggs or by larvae boring through the wood (Fig. 3a-b). The clean-cut appearance of the hole suggests recent activity (Fig. 3b). Numerous circular holes indicate the advance of colonization where multiple larvae have burrowed, compromising the structural integrity of the palm and contributing to its decline (Fig. 2f, 3a). Internal damage is characterized by a discolored and brittle texture of the bark, the texture of the wood appears spongy and degraded, illustrating the destruction caused by the feeding larvae (Fig. 3d-f).

The female lays her eggs on decomposing organic matter, such as fallen trunks or palm tree remains from previous crops, where she builds galleries. Larvae feed in the stipe-trunk, forming wide galleries toward the bulb of the palm. Larva built pupal chambers where the immature individuals develop until they emerge from the host (Fig. 3e-f). The different larval stages of the bearded weevil develop in these substrates, and the larvae can be found buried at a depth of 30-40 cm (Fig. 3f). Within the stipe and bulb tissues, different life stages of the weevil can be found including larvae, pupae, and adult insects (Fig. 3e). In only one specimen of the palm, dozens of beetles can be found (Fig. 3f). The variables HP, DOP and NP reported the following information obtained at the sampling sites: HP (0.85-1.35 m; µ = 1.10 m), DOP (45-158 mm, µ = 107.4 mm) and NP (1-17, µ = 7). Adult individuals and larvae are responsible for the damage (Fig. 3a-c), which begins with the excavation of tunnels in the soil until reaching the basal bulb, which is completely consumed. Subsequently, the insect ascends the plant to feed on the apical tissue, causing the death of the plant. The presence of mounds of fresh soil, like small hills built by the insect, reveals its presence, especially in areas with decaying trunks, which serve as incubators for future generations (Fig. 3e-f). Additionally, in B. dulcis palms with damage attributed to R. barbirostris, the presence of beetles from the Zopheridae family (Zopherus spp.) was recorded (Fig. 3a) in areas of plant tissue that were in an advanced state of deterioration and decomposition, confirming a direct association with the initial damage caused by the weevil.

A total of 506 geographic records of the bearded weevil were obtained in 2023 in Mexican territory, 3 from AMNH, 1 from ASU, 4 from CECR, 17 from CEAM, 67 from CNIN-UNAM, 123 from Conafor, 6 from DGSV, 2 from ECOSUR, 214 from iNaturalist, 4 from MZFC and 4 from UACH (Table 1). The oldest record for this species corresponds to Playa Vicente (17°49’46.98”N, 95°48’47.12”O) and Actopan (19°30’16.14”N, 96°36’56.82”O), Veracruz reported by Champion (1910) under the name Rhina barbirostris. In Mexico, the number of records from 1927 to 2006 was 101 records; from 2007 to 2023 the collection of specimens and sightings increased to 337 records and 68 records without collection data (Table 1). In last decade (2013-2013), sampling efforts increased, mainly in the states of: Chiapas (23), Jalisco (24), Oaxaca (147), Quintana Roo (26), Sinaloa (24) and Veracruz (46). With a total of 2 records, the Sierra Negra de Puebla was the locality with the lowest number of records for the bearded weevil. The bearded weevil was most abundantly collected from march to december with a total of 251 specimens, corresponding to 49.59% of a total of individuals.

Based on the records of the collections and consulting the available literature it was possible to obtain information about the host plant of the adult individuals of R. barbirostris present in Mexico and throughout its distribution. These correspond to Attalea funifera, A. maripa A. pindobossu, A. piassabossu, Bactris gasipes, Brahea dulcis, Cocos botryophora, C. coronata, C. nucifera, Elaeis guineensis, Euterpe oleraceae, Mauritia flexuosa, Oenocarpa bacaba, Syagrus romanzoffiana and S. schizophylla (Table 2).

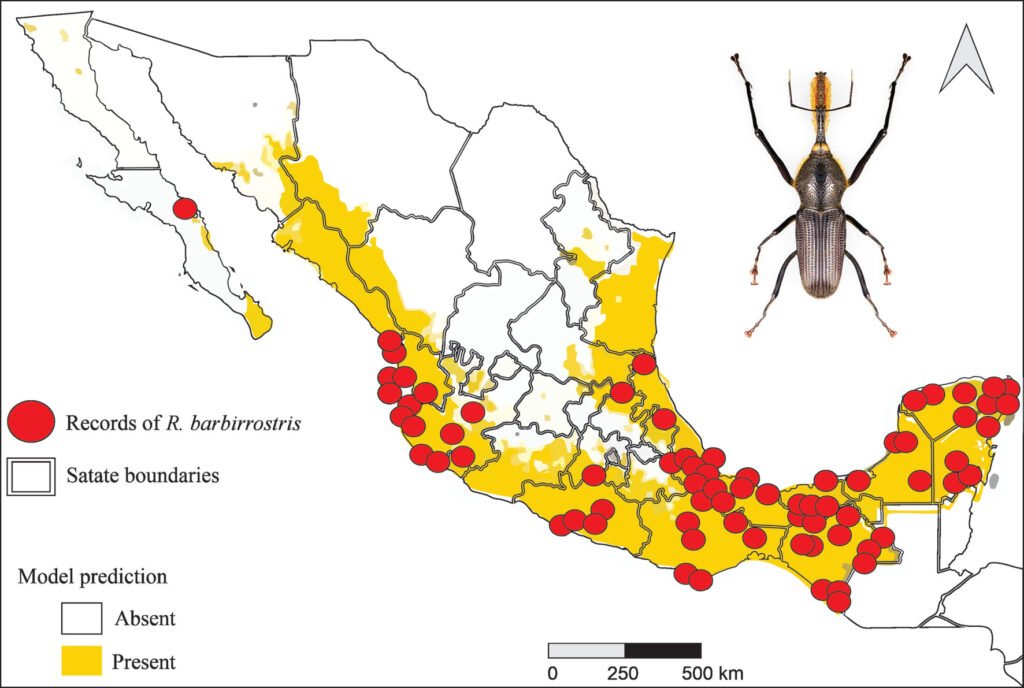

The potential distribution model developed with the Wallace platform revealed that this species has a surprisingly wide distribution in Mexico (Fig. 4). The model predicts the most likely areas for the species based on historical records of its presence (red dots on the map). To ensure the robustness of the analysis, we chose a model with a linear feature and a regularization multiplier of 1, allowing us to avoid overfitting and obtain more reliable results. Although AUC curves are a common metric, they are not included here due to differences in how Wallace calculates them compared to the MaxEnt Java application. Overall, the findings indicate that the species is capable of inhabiting a large portion of the national territory; although the species is present in many regions, a higher concentration of records was observed in certain areas, such as Sierra Madre Oriental (SMOR), Sierra Madre Occidental (SMOC), and Sierra Madre del Sur (SMAS). Although the distribution of this taxon is correlated with environmental factors such as vegetation, altitude, and climatic conditions, human intervention emerges as a determining factor in its dispersal pattern. Activities such as the movement of infested plant material through agricultural campaigns or the transport of goods act as key vectors, overcoming natural geographic and ecological barriers. This accelerated dispersal allows the species to colonize new territories with unprecedented speed and scope. Therefore, for a complete understanding of its current distribution, it is essential to complement the analysis of environmental factors with a thorough assessment of how human activities are shaping the geography of the species.

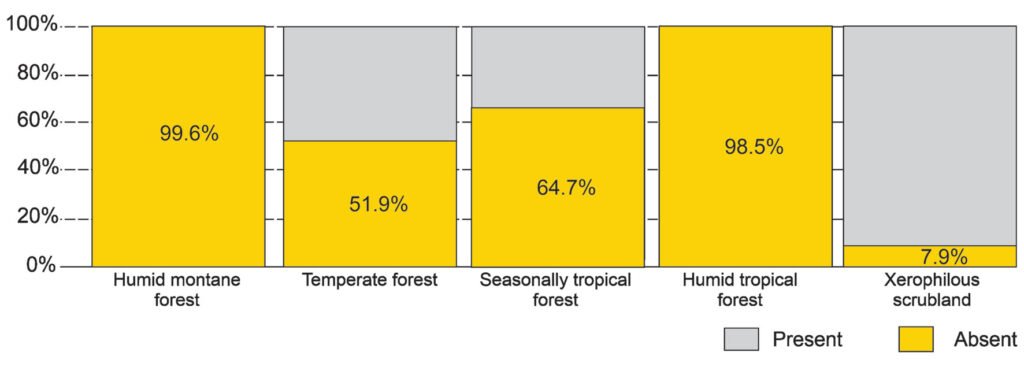

The potential distribution model covers almost the entire surface area in the national territory of 2 of the biomes: humid mountain forest (99.6%) and humid tropical forest (98.5%); in 2 others, close to half: temperate forest (51.9%) and seasonally dry tropical forest (64.7%); and only 7.9% in xerophilous scrubland (Fig. 5).

Discussion

Our field observations provide detailed evidence of the damage associated with R. barbirostris colonizing B. dulcis and allow for the description of key aspects of the biology of this weevil. As in Brazilian coconut plantations, we documented that the axils of older leaves of B. dulcis serve as a refuge for R. barbirostris (Ferreira, 2008). Although we did not record beetle eggs, the presence of adults in older axils suggests that oviposition may occur in the stem, and once hatched, larvae penetrate and form galleries (Ferreira, 2008; Lacerda-Moura et al., 2013). One of the characteristics associated with the colonization holes was the exudation of a dark reddish-brown liquid, which is consistent with gummosis disease or trunk bleeding caused by the fungus Ceratocystis paradoxa (Dade) C. Moreau anamorph in the coconut palm, which has been associated with the presence of R. barbirostris (Ferreira et al., 2007). Further studies are needed to determine whether the susceptibility of sweet palm is related to the presence of this fungus, as it is reported that C. paradoxa releases a semiochemical that attracts these beetles (Lacerda-Moura et al. 2013). Furthermore, that R. barbirostris is also mentioned as a vector of the nematode Bursaphelenchus cocophilus (Cobb.) (Goodey, 1933,1960) in the coconut groves (Franco, 1964).

Larval galleries in the bulb of B. dulcis, as well as the progressive destruction of apical tissues, reflect a strategy of underground colonization of R. barbirostris followed by upward expansion into the aerial parts of the plant. This behavior is consistent with that of R. barbirrostris in Brazil (Lacerda-Moura et al., 2013) and that of other palm-associated curculionids, in which the larval stage is the most destructive, feeding of internal tissues and compromising the structural integrity of the host (Faleiro, 2006; Soroker et al., 2015).

The coexistence of larvae, pupae, and adults within a single palm individual indicates that R. barbirostris exhibits a continuous life cycle inside its host, ensuring the local persistence of its populations. Similar patterns have been reported for the red palm weevil Rhynchophorus ferrugineus, where overlapping generations occur within the same palm and infestations are difficult to eradicate once established (Abraham et al., 1998; Dembilio & Jacas, 2011). The ability of R. barbirostris larvae to burrow 30-40 cm underground and construct pupal chambers in degraded tissues highlights a high degree of adaptation to concealed and protected habitats, reducing exposure to natural enemies and environmental fluctuations. Such cryptic development has also been documented in Rhynchophorus palmarum, a major pest of coconut and oil palms in the Neotropics (Griffith, 1987), and in Metamasius hemipterus, another palm-infesting weevil (Weissling & Giblin-Davis, 1993).

Table 1. Records of Rhinostomus barbirostris in Mexico by date, federal entity, geographical coordinates and site 556 of specimen consultation.

| Date | Locality | Latitude | Longitude | Altitude (m asl) | Host | Number of specimens | Source |

| 24/03/1973 | 35kms al sur de Mulejé, Baja california, Mexico | 26°53’29.82” | 111°59’0.79” | 16 | N/A | 24 | CNIN-UNAM |

| 24/03/1973 | 25kms al sur de Mulejé, Baja California, Mexico | 26°53’31.95” | 111°59’0.91” | 30 | N/A | 6 | CNIN-UNAM |

| 20/10/1971 | Campeche, Mexico | 19°49’48.15” | 90°32’5.61” | 3 | N/A | 1 | CNIN-UNAM |

| 16/12/2016 | Calakmul Municipality, Campeche, Mexico | 18°25’37.86” | 89°42’1.62” | 232 | N/A | 4 | iNaturalist |

| 10/02/2021 | Municipio de Carmen, Campeche, Mexico | 18°30’59.31” | 91°26’36.71” | 0 | N/A | 2 | iNaturalist |

| 24/02/2022 | 24327 Campeche, Mexico | 18°39’8.16” | 91°33’29.90” | 0 | N/A | 2 | iNaturalist |

| 27/05/1981 | Ejido 2 de Mayo, Chiapas, Mexico | 15°1’46.44” | 92°8’55.34” | 698 | N/A | 1 | DGSV |

| 27/05/1981 | Campo experimental Rosario Izapa, Chiapas, Mexico | 14°58’30.32” | 92°9’19.13” | 445 | N/A | 1 | DGSV |

| 27/03/1982 | Benemérito de las America, “s-palapa”, Chiapas, Mexico | 16°30’51.36” | 90°39’14.75” | 141 | N/A | 1 | MZFC |

| 19/05/1984 | Palenque, Chiapas, Mexico | 17°30’39.36” | 91°59’34.98” | 71 | N/A | 1 | CNIN-UNAM |

| 28/04/1986 | Ocosingo Chajul, Reserva Montes Azules, Chiapas | 16°35’51.21” | 91°9’9.44” | 747 | N/A | 3 | CNIN-UNAM |

| 25/07/2013 | Chiapas, Mexico | 16°45’24.82” | 93°7’45.25” | 535 | N/A | 1 | iNaturalist |

| 10/10/2015 | Las Nubes, Chiapas, Mexico | 16°11’44.85” | 91°20’20.73” | 287 | N/A | 2 | iNaturalist |

| 25/07/2017 | Tapachula, Chiapas, Mexico | 14°54’19.82” | 92°15’48.29” | 173 | N/A | 2 | iNaturalist |

| N/A | Tapachula, Chiapas, Mexico | 14°54’19.82” | 92°15’48.29” | 173 | N/A | 4 | N/A |

| 12/12/2018 | Ocosingo, Chiapas, Mexico | 16°54’24.54” | 92°5’39.53” | 849 | N/A | 3 | iNaturalist |

| 03/01/2019 | Villa Comaltitlán, Chiapas, Mexico | 15°12’45.24” | 92°34’34.50” | 34 | N/A | 1 | iNaturalist |

| 29/05/2019 | Finca La Alianza, Municipio Cacahoatán, Chiapas, Mexico | 15°2’36.93” | 92°10’52.66” | 687 | N/A | 1 | ECOSUR |

| 09/06/2019 | Ejido las nubes, Municipio Tapachula, Chiapas, Mexico | 14°52’26.05” | 92°16’4.11” | 130 | N/A | 1 | ECOSUR |

| 02/08/2019 | Calle San José, Tapachula de Córdova y Ordoñez, Chiapas, Mexico | 14°52’39.33” | 92°16’25.01” | 121 | N/A | 5 | iNaturalist |

| 30/04/2020 | Chiapas, Mexico | 16°45’24.82” | 93°7’45.25” | 535 | N/A | 1 | iNaturalist |

| 05/01/2020 | Tapachula, Chiapas, Mexico | 14°54’19.82” | 92°15’48.29” | 173 | N/A | 2 | iNaturalist |

| 17/04/2021 | Hotel Argovia Finca Resort, Chiapas, Mexico | 15°7’31.20” | 92°17’55.92” | 625 | N/A | 4 | iNaturalist |

| 27/11/2022 | 29935 Ocosingo, Chiapas, Mexico | 16°46’6.24” | 90°56’37.83” | 171 | N/A | 1 | iNaturalist |

| N/A | Chiapas, Mexico | 16°45’20.31” | 93°7’45.41” | 533 | Coccos nucifera | 1 | CEAM |

| N/A | Colima, Mexico | 19°14’42.27” | 103°43’26.51” | 503 | N/A | 1 | iNaturalist |

| X/05/1948 | Cacahuamilpa, Guerrero, Mexico | 18°40’53.77” | 99°30’19.96” | 1,266 | N/A | 1 | iNaturalist |

| 19/09/1963 | Guerrero, Mexico | 17°26’21.02” | 99°32’42.29” | 2,136 | N/A | 1 | DGSV |

| 14/11/1971 | Técpan de Galeana, Guerrero, Mexico | 17°13’22.27” | 100°37’42.16” | 45 | N/A | 1 | CNIN-UNAM |

| Table 1. Continued | |||||||

| Date | Locality | Latitude | Longitude | Altitude (m asl) | Host | Number of specimens | Source |

| 14/11/1971 | Rodecia, Guerrero, Mexico | 17°12’24.68” | 100°41’56.90” | 22 | N/A | 3 | CNIN-UNAM |

| 03/11/1976 | Ejido de Tenexpa, Tecpán de Galeana, Guerrero, Mexico | 17°11’0.17” | 100°40’16.97” | 16 | Coccos nucifera | 7 | CEAM |

| 02/02/1976 | Petatlán, Guerrero, Mexico | 17°32’20.41” | 101°16’12.70” | 35 | Coccos nucifera | 2 | CEAM |

| 02/02/1976 | Petatlán, Guerrero, Mexico | 17°32’20.41” | 101°16’12.70” | 35 | Coccos nucifera | 2 | CECR |

| 24/02/1976 | Petatlán, Guerrero, Mexico | 17°32’20.41” | 101°16’12.70” | 35 | Coccos nucifera | 4 | CEAM |

| 24/02/1976 | Petatlán, Guerrero, Mexico | 17°32’20.41” | 101°16’12.70” | 35 | Coccos nucifera | 2 | CECR |

| X/05/1985 | Cacahuamilpa, Guerrero, Mexico | 18°40’53.77” | 99°30’19.96” | 1,266 | N/A | 1 | CNIN-UNAM |

| 10/07/2007 | Guerrero, Mexico | 17°26’21.02” | 99°32’42.29” | 2,136 | N/A | 1 | iNaturalist |

| 07/10/2007 | Reforma 4ta Etapa, Chilpancingo de los Bravo, Guerrero, Mexico | 17°32’11.71” | 99°28’49.61” | 1,330 | N/A | 3 | iNaturalist |

| 28/12/2022 | Guerrero, Mexico | 17°26’21.02” | 99°32’42.29” | 2,136 | N/A | 1 | iNaturalist |

| 28/12/2022 | Chilpancingo de los Bravo, Guerrero, Mexico | 17°32’21.67” | 99°29’4.65” | 1,302 | N/A | 3 | iNaturalist |

| 06/10/2022 | Puerto del gallo, Guerrero, Mexico | 17°28’1.50” | 100°10’32.63” | 2,252 | N/A | 1 | CNIN-UNAM |

| 17/09/2016 | Yelapa, Jalisco, Mexico | 20°29’16.29” | 105°26’53.44” | 19 | N/A | 1 | iNaturalist |

| 23/09/2016 | Yelapa, Jalisco, Mexico | 20°29’16.29” | 105°26’53.44” | 19 | N/A | 2 | iNaturalist |

| 06/12/2017 | Yelapa, Jalisco, Mexico | 20°29’16.29” | 105°26’53.44” | 19 | N/A | 2 | iNaturalist |

| 27/06/2018 | Yelapa, Jalisco, Mexico | 20°29’16.29” | 105°26’53.44” | 19 | N/A | 2 | iNaturalist |

| 09/11/2019 | Yelapa, Jalisco, Mexico | 20°29’16.29” | 105°26’53.44” | 19 | N/A | 1 | iNaturalist |

| 09/12/2019 | Yelapa, Jalisco, Mexico | 20°29’16.29” | 105°26’53.44” | 19 | N/A | 2 | iNaturalist |

| 25/07/2020 | Yelapa, Jalisco, Mexico | 20°29’16.29” | 105°26’53.44” | 19 | N/A | 1 | iNaturalist |

| 12/11/2021 | Cabo Corrientes, Jalisco, Mexico | 20°19’6.02” | 105°19’17.70” | 607 | N/A | 3 | iNaturalist |

| 13/06/2022 | Yelapa, Jalisco, Mexico | 20°29’16.29” | 105°26’53.44” | 20 | N/A | 1 | iNaturalist |

| 09/09/2022 | Yelapa, Jalisco, Mexico | 20°29’16.29” | 105°26’53.44” | 19 | N/A | 2 | iNaturalist |

| 25/10/2022 | Jalisco, Mexico | 20°39’32.98” | 103°20’57.86” | 1,545 | N/A | 1 | iNaturalist |

| 25/03/2022 | Paseo de las Conchas, Puerto Vallarta, Jalisco, Mexico | 20°35’15.46” | 105°14’29.19” | 99 | N/A | 3 | iNaturalist |

| 26/10/2022 | Cihuatlán, Jalisco, Mexico | 19°14’15.50” | 104°34’6.38” | 42 | N/A | 2 | iNaturalist |

| 06/07/2023 | 48898 Jalisco, Mexico | 19°16’47.08” | 104°47’9.22” | 66 | N/A | 1 | iNaturalist |

| N/A | La Lima, Jalisco, Mexico | 20°0’7.13” | 103°59’5.06” | 1,228 | N/A | 1 | iNaturalist |

| 18/02/1981 | Cuernavaca, Morelos, Mexico | 18°55’27.04” | 99°13’17.61” | 1,510 | N/A | 1 | MZFC |

| 12/06/2012 | La puntilla, Nayarit, Mexico | 22°28’8.45” | 105°43’21.08” | 8 | N/A | 1 | DGSV |

| 28/10/2013 | Los Otates, Nayarit, Mexico | 21°42’10.89” | 105°22’29.99” | 6 | N/A | 1 | DGSV |

| 08/11/2019 | Av. Revolución 7, Sayulita, Nayarit, Mexico | 20°52’7.35” | 105°26’14.41” | 9 | N/A | 2 | iNaturalist |

| 19/10/2020 | Bahía de Banderas, Nayarit, Mexico | 20°48’26.06” | 105°14’53.25” | 39 | N/A | 2 | iNaturalist |

| 30/12/2022 | Bahía de Banderas, Nayarit, Mexico | 20°48’26.06” | 105°14’53.25” | 39 | N/A | 2 | iNaturalist |

| 23/04/2023 | Compostela, Nayarit, Mexico | 21°14’11.66” | 104°54’2.86” | 879 | N/A | 2 | iNaturalist |

| N/A | Acaponeta, Nayarit, Mexico | 22°29’45.35” | 105°21’46.40” | 30 | N/A | 1 | N/A |

| N/A | Compostela, Nayarit, Mexico | 21°14’12.03” | 104°54’2.61” | 852 | N/A | 1 | N/A |

| N/A | San Blás, Nayarit, Mexico | 21°32’28.60” | 105°17’4.98” | 5 | N/A | 1 | N/A |

| N/A | Tepic, El Cora, Nayarit, Mexico | 21°30’14.30” | 104°53’40.43” | 932 | N/A | 1 | N/A |

| 1-4/09/1947 | Tolosa, Oaxaca, Mexico | 22°31’20.28” | 101°21’23.68” | 2,095 | N/A | 3 | AMNH |

| 30/05/1959 | S. Carlos, Palomares N de Oaxaca, Mexico | 17°4’22.64” | 96°43’35.52” | 1,604 | N/A | 1 | CNIN-UNAM |

| X/07/1970 | Sierra de Juárez, Oaxaca, Mexico | 17°34’46.53” | 17°34’46.53” | 1,730 | N/A | 1 | CNIN-UNAM |

| 01/07/1996 | Topiltepec, Oaxaca, Mexico | 17°26’14.23” | 97°20’41.66” | 2,173 | Brahea dulcis | 4 | UACH |

| 27/05/2014 | Oaxaca, Mexico | 17°4’23.33” | 96°43’35.80” | 1,589 | N/A | 1 | iNaturalist |

| 02/04/2015 | Oaxaca, Mexico | 17°4’23.33” | 96°43’35.80” | 1,589 | N/A | 3 | iNaturalist |

| 16/01/2018 | Loma Bonita, Oaxaca, Mexico | 18°6’34.71” | 95°52’49.39” | 35 | N/A | 4 | iNaturalist |

| 16/01/2018 | Oaxaca, Mexico | 17°4’23.33” | 96°43’35.80” | 1,589 | N/A | 1 | iNaturalist |

| 19/06/2018 | Tuxtepec-San Felipe Jalapa de Díaz, San Bartolo, Oaxaca, Mexico | 16°57’13.90” | 96°42’28.63” | 1,520 | N/A | 2 | iNaturalist |

| 28/05/2018 | Calle9 de Marzo, San José de las Flores, Oaxaca, Mexico | 17°20’59.44” | 95°23’51.72” | 60 | N/A | 3 | iNaturalist |

| 06/04/2019 | La laguna del palmar, Oaxaca, Mexico | 15°41’54.20” | 96°36’45.93” | 17 | N/A | 1 | iNaturalist |

| 21/01/2020 | Oaxaca, Mexico | 17°4’23.33” | 96°43’35.80” | 1,590 | N/A | 1 | iNaturalist |

| 22/01/2020 | Santa María Tonameca, Oaxaca, Mexico | 15°44’47.94” | 96°32’46.59” | 32 | N/A | 1 | iNaturalist |

| 21/12/2022 | 70949 Oaxaca, Mexico | 15°45’0.15” | 96°41’6.71” | 92 | N/A | 3 | iNaturalist |

| 26/07/2007 | Sierra Negra, Puebla, Mexico | 18°58’59.43” | 97°19’0.16” | 4,450 | N/A | 2 | iNaturalist |

| X/02/2022 | Santa María Almoloyas, Oaxaca | 17°36’30.42 “ | 97°1’25.08” | 1,734 | N/A | 25 | Conafor |

| X/02/2022 | San Juan Tonaltepec, Oaxaca | 17°30’58.66 “ | 96°54’43.89” | 1,823 | N/A | 18 | Conafor |

| X/02/2022 | San Pedro, Nodón, Oaxaca | 17°47’58.94 “ | 97°7’36.00” | 1,686 | N/A | 10 | Conafor |

| X/02/2022 | San Pedro Jaltepetongo, Oaxaca | 17°41’15.56 “ | 97°2’13.65” | 1,796 | N/A | 9 | Conafor |

| X/02/2022 | Santa María Ixcatlán, Oaxaca | 17°51’8.71” | 97°11’32.76” | 1,895 | N/A | 8 | Conafor |

| X/02/2022 | Santa María Cotahuixtla, Oaxaca | 17°31’45.00” | 96°54’41.00” | 2,035 | N/A | 12 | Conafor |

| X/02/2022 | Santiago Nacaltepec, Oaxaca | 17°30’58.68” | 96°54’43.90” | 2,052 | N/A | 10 | Conafor |

| X/02/2022 | San Pedro Jaltepetongo, Oaxaca | 17°41’15.56” | 97°2’13.65” | 1,798 | N/A | 20 | Conafor |

| X/02/2022 | San Pedro Jocotipac, Oaxaca | 17°46’6.02” | 97°4’42.39” | 2,034 | N/A | 11 | Conafor |

| N/A | Escuilapa, Oaxaca, Mexico | 16°50’58.18” | 94°45’58.82” | 230 | N/A | 1 | CNIN-UNAM |

| N/A | Río Escuilapa, Oaxaca, Mexico | 16°50’58.18” | 94°45’58.82” | 230 | N/A | 1 | CNIN-UNAM |

| N/A | Oaxaca, Oaxaca Mexico | 17°4’23.33” | 96°43’35.80” | 1,589 | N/A | 20 | N/A |

| N/A | Tolosa, Oaxaca, Mexico | 22°31’20.28” | 101°21’23.68” | 2,095 | N/A | 17 | N/A |

| 16/12/2016 | Chiquilá, Quintana Roo, Mexico | 21°25’33.39” | 87°20’24.42” | 5 | N/A | 4 | iNaturalist |

| 11/11/2016 | Quintana Roo, Mexico | 19°10’51.16” | 88°28’44.67” | 18 | N/A | 3 | iNaturalist |

| 16/06/2017 | Benito Juárez, Quintana Roo, Mexico | 21°6’50.28” | 86°56’32.58” | 8 | N/A | 3 | iNaturalist |

| 29/01/2017 | Quintana Roo, Mexico | 19°10’51.16” | 88°28’44.67” | 18 | N/A | 4 | iNaturalist |

| 21/12/2019 | Quintana Roo, Mexico | 18°36’23.25” | 88°0’42.66” | 7 | N/A | 2 | iNaturalist |

| 09/11/2020 | Quintana Roo, Mexico | 18°36’23.25” | 88°0’42.66” | 7 | N/A | 1 | iNaturalist |

| 17/09/2020 | Lázaro Cárdenas, Quintana Roo, Mexico | 20°47’20.04” | 87°27’37.42” | 25 | N/A | 3 | iNaturalist |

| 07/10/2021 | 77584 Quintana Roo, Mexico | 20°54’38.15” | 86°53’32.21” | 5 | N/A | 2 | iNaturalist |

| 08/02/2021 | Calle 33, Tulum, Quintana Roo, Mexico | 20°12’53.40” | 87°28’38.56” | 12 | N/A | 2 | iNaturalist |

| 30/08/2021 | Bacalar, Quintana Roo, Mexico | 18°40’41.69” | 88°23’32.64” | 18 | N/A | 2 | iNaturalist |

| N/A | X-Can, Quintana Roo, Mexico | 20°52’8.93” | 87°36’11.00” | 24 | N/A | 1 | N/A |

| 15/08/2018 | Escuinapa, Sinaloa, Mexico | 22°50’44.16” | 105°54’4.68” | 20 | N/A | 4 | iNaturalist |

| 30/08/2019 | Escuinapa, Sinaloa, Mexico | 22°50’44.16” | 105°54’4.68” | 20 | N/A | 2 | iNaturalist |

| 12/09/2019 | Escuinapa, Sinaloa, Mexico | 22°50’44.16” | 105°54’4.68” | 20 | N/A | 2 | iNaturalist |

| 29/04/2023 | Escuinapa, Sinaloa, Mexico | 22°50’44.16” | 105°54’4.68” | 20 | N/A | 12 | iNaturalist |

| 30/04/2023 | Sinaloa, Mexico | 22°50’44.16” | 105°54’4.68” | 20 | N/A | 3 | iNaturalist |

| 30/04/2023 | Carretera Escuinapa-Teacapan km14,82532 Sinaloa, Mexico | 22°32’17.93” | 105°44’13.07” | 4 | N/A | 1 | iNaturalist |

| N/A | Without precise data, Tabasco, Mexico | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2 | MZFC |

| X/X/1936 | Frontera, Tabasco. | 18°28’11.86” | 92°39’47.00” | 0 | N/A | 1 | CNIN-UNAM |

| X/07/1970 | Finca Los Pinos, Tabasco, Cárdenas | 17°55’38.37” | 93°1’48.32” | 8 | N/A | 1 | CEAM |

| 20/01/1971 | Chontalpa, Tabasco, Mexico | 17°39’52.67” | 93°28’47.47” | 54 | N/A | 1 | CNIN-UNAM |

| 25/06/1989 | Teapa, Tabasco, Mexico | 17°33’39.32” | 92°57’7.13” | 32 | Coccos nucifera | 1 | CEAM |

| 08/11/2020 | Huimanguillo, Tabasco, Mexico | 17°49’50.50” | 93°23’23.01” | 37 | N/A | 1 | iNaturalist |

| 22/04/2020 | Teapa, Tabasco, Mexico | 17°34’1.50” | 92°57’0.21” | 38 | N/A | 2 | iNaturalist |

| 07/10/2022 | Buenos Aires,86707 Macuspana, Tabasco, Mexico | 17°45’55.70” | 92°35’19.88” | 13 | N/A | 1 | iNaturalist |

| 06/02/2022 | Centro, Tabasco, Mexico | 17°59’28.47” | 92°56’3.91” | 16 | N/A | 1 | iNaturalist |

| X/X/1927 | Veracruz Ignacio de la Llave, Mexico | 19°10’24.98” | 96°8’3.10” | 6 | N/A | 1 | DGSV |

| X/12/1942 | Veracruz Ignacio de la Llave, Mexico | 19°10’24.98” | 96°8’3.10” | 6 | N/A | 1 | CNIN-UNAM |

| 29/10/1953 | Camto, Ciudad Alemán, Veracruz, Mexico | 18°11’47.14” | 96°5’9.71” | 16 | N/A | 1 | CNIN-UNAM |

| X/10/1953 | Ciudad Alemán, Veracruz, Mexico | 18°11’47.14” | 96°5’9.71” | 16 | N/A | 1 | CNIN-UNAM |

| X/10/1954 | Ciudad Alemán, Veracruz, Mexico | 18°11’47.14” | 96°5’9.71” | 16 | N/A | 1 | CNIN-UNAM |

| 17/06/1958 | Ciudad Alemán, Veracruz, Mexico | 18°11’47.14” | 96°5’9.71” | 16 | N/A | 1 | CNIN-UNAM |

| 09/05/1975 | Estación de Biología Los Tuxtlas, Veracruz, Mexico | 18°35’5.61” | 95°4’26.15” | 149 | N/A | 4 | CNIN-UNAM |

| 18/05/1974 | Los Tuxtlas, Veracruz, Mexico | 18°35’5.61” | 95°4’26.15” | 148 | N/A | 1 | CNIN-UNAM |

| X/03/1983 | Los Tuxtlas, Veracruz, Mexico | 18°35’5.61” | 95°4’26.15” | 148 | N/A | 1 | CNIN-UNAM |

| 16/08/1985 | Estación de Biología Los Tuxtlas, Veracruz, Mexico | 18°35’5.61” | 95°4’26.15” | 148 | N/A | 1 | CNIN-UNAM |

| 28/05/1986 | Estación de Biología Los Tuxtlas, Veracruz, Mexico | 18°35’5.61” | 95°4’26.15” | 148 | N/A | 1 | CNIN-UNAM |

| 28/04/1986 | Estación de Biología Los Tuxtlas, Veracruz, Mexico | 18°35’5.61” | 95°4’26.15” | 149 | N/A | 3 | CNIN-UNAM |

| 04/11/1988 | Estación de Biología Los Tuxtlas, Veracruz, Mexico | 18°35’5.61” | 95°4’26.15” | 148 | N/A | 1 | ASU |

| 22/03/1989 | Estación de Biología Los Tuxtlas, Veracruz, Mexico | 18°35’5.61” | 95°4’26.15” | 148 | N/A | 1 | CNIN-UNAM |

| 07/04/1989 | Estación de Biología Los Tuxtlas, Veracruz, Mexico | 18°35’5.61” | 95°4’26.15” | 149 | N/A | 1 | CNIN-UNAM |

| 04/05/1989 | Estación de Biología Los Tuxtlas, Veracruz, Mexico | 18°35’5.61” | 95°4’26.15” | 149 | N/A | 1 | CNIN-UNAM |

| 14/07/1989 | Estación de Biología Los Tuxtlas, Veracruz, Mexico | 18°35’5.61” | 95°4’26.15” | 148 | N/A | 1 | CNIN-UNAM |

| 02/10/2006 | Veracruz, Mexico | 19°10’24.98” | 96°8’3.10” | 6 | N/A | 1 | iNaturalist |

| 10/02/2006 | San Andrés Tuxtla, Veracruz, Mexico | 18°26’38.74” | 95°12’46.89” | 157 | N/A | 2 | iNaturalist |

| 19/05/2007 | Los Tuxtlas Veracruz, San Adres Tuxtla, Mexico | 18°26’38.74” | 95°12’46.89” | 284 | N/A | 1 | CEAM |

| 16/04/2012 | Veracruz, Mexico | 19°10’24.98” | 96°8’3.10” | 6 | N/A | 1 | iNaturalist |

| 16/04/2012 | Km. 30 carretera Catemaco Montepío,95701 San Andrés, Veracruz, Mexico | 18°38’29.84” | 95°5’41.07” | 148 | N/A | 1 | iNaturalist |

| 09/12/2013 | Veracruz, Mexico | 19°10’24.98” | 96°8’3.10” | 6 | N/A | 1 | iNaturalist |

| 12/09/2013 | Estación de Biología Los Tuxtlas, Veracruz, Mexico | 18°35’5.61” | 95°4’26.15” | 148 | N/A | 4 | iNaturalist |

| 23/06/2014 | 92018 Tamos, Veracruz, Mexico | 22°13’4.71” | 97°59’40.65” | 12 | N/A | 1 | iNaturalist |

| 07/05/2015 | Veracruz, Mexico | 19°10’24.98” | 96°8’3.10” | 6 | N/A | 1 | iNaturalist |

| 16/05/2015 | Veracruz, Mexico | 19°10’24.98” | 96°8’3.10” | 6 | N/A | 1 | iNaturalist |

| 05/07/2015 | San Andrés Tuxtla, Veracruz, Mexico | 18.585211 | 95°12’46.89” | 157 | N/A | 3 | iNaturalist |

| 26/05/2015 | San Andrés Tuxtla, Veracruz, Mexico | 18°26’38.74” | 95°12’46.92” | 283 | N/A | 3 | iNaturalist |

| 01/05/2016 | Catemaco Veracruz, Mexico | 18°25’16.49” | 95°6’46.68” | 358 | N/A | 3 | iNaturalist |

| 09/04/2016 | Veracruz, Mexico | 19°10’24.98” | 96°8’3.10” | 6 | N/A | 1 | iNaturalist |

| 13/05/2016 | Veracruz, Mexico | 19°10’24.98” | 96°8’3.10” | 6 | N/A | 3 | iNaturalist |

| 28/05/2016 | Veracruz, Mexico | 19°10’24.98” | 96°8’3.10” | 6 | N/A | 1 | iNaturalist |

| 04/10/2016 | San Andrés Tuxtla, Veracruz, Mexico | 18°26’38.74” | 95°12’46.89” | 157 | N/A | 3 | iNaturalist |

| 19/05/2016 | San Andrés Tuxtla, Veracruz, Mexico | 18°26’38.74” | 95°12’46.89” | 157 | N/A | 3 | iNaturalist |

| 28/06/2016 | Estación de Biología Los Tuxtlas, Veracruz, Mexico | 18°35’5.61” | 95°4’26.15” | 148 | N/A | 3 | iNaturalist |

| 10/05/2019 | Km. 30 carretera Catemaco Montepío, Tuxtla, 95701 San Andrés, Veracruz, Mexico | 18°38’27.94” | 95°5’41.42” | 18 | N/A | 1 | iNaturalist |

| 09/11/2020 | González Ortega, Veracruz, Mexico | 20°25’18.27” | 97°27’57.07” | 210 | N/A | 2 | iNaturalist |

| 15/07/2020 | 95084 Acatlán – Tezonapa, Veracruz, Mexico | 18°34’4.43” | 96°38’46.22” | 155 | N/A | 2 | iNaturalist |

| 26/9/2020 | El Nopo, Veracruz, Mexico | 18°29’7.02” | 95°6’57.37” | 723 | N/A | 1 | iNaturalist |

| 08/11/2021 | 96366 Veracruz, Mexico | 18°1’37.28” | 94°26’1.11” | 22 | N/A | 2 | iNaturalist |

| 07/02/2022 | 95226 Veracruz, Mexico | 18°47’16.21” | 96°12’20.62” | 27 | N/A | 2 | iNaturalist |

| 08/05/2022 | 94224 Veracruz, Mexico | 19°4’14.38” | 96°49’37.43” | 813 | N/A | 1 | iNaturalist |

| 04/08/2022 | Veracruz, Mexico | 19°10’24.98” | 96°8’3.10” | 6 | N/A | 1 | iNaturalist |

| 07/02/2023 | Veracruz, Mexico | 19°10’24.98” | 96°8’3.10” | 6 | N/A | 1 | iNaturalist |

| 02/08/2023 | Camarón de Tejeda, Veracruz, Mexico | 19°1’21.33” | 96°36’50.56” | 348 | N/A | 2 | iNaturalist |

| N/A | Jalapa, Veracruz, Mexico | 19°32’36.56” | 96°54’36.63” | 1,408 | N/A | 10 | N/A |

| N/A | Motzorongo, Veracruz, Mexico | 18°38’29.77” | 96°43’53.21” | 272 | N/A | 4 | N/A |

| N/A | Rio Quezalapan, east of Lake Catemaco, Veracruz, Mexico | 18°25’16.49” | 95°6’46.68” | 358 | N/A | 1 | N/A |

| 06/05/2019 | Candelaria, Valladolid, Yucatán, Mexico | 20°41’43.63” | 88°12’21.42” | 22 | N/A | 3 | iNaturalist |

| 17/06/2019 | Centro,97700 Tizimín, Yucatán, Mexico | 21°8’46.38” | 88°8’46.37” | 19 | N/A | 3 | iNaturalist |

| 31/01/2020 | Hunucmá, Yucatán, Mexico | 21°0’58.71” | 89°52’38.03” | 8 | N/A | 4 | iNaturalist |

| 30/06/2022 | 97439 Yucatán, Mexico | 21°14’51.51” | 89°24’28.77” | 8 | N/A | 3 | iNaturalist |

Table 2. Records of hosts attacked by R. barbirostris by country, locality, source, common name and distribution.

| Host | Country | Locality | Source | Common name | Distribution |

| Attalea funifera, A. maripa A. pindobossu, A. piassabossu | Venezuela | N/D | Vaurie,1970; Choo et al., 2010 | Casicusi, cucurito, cusi, cusi macho, inayu, motacusillo | Northern South America in Colombia, Venezuela, Trinidad and Tobago (Caribbean), Peru, Guianas, Ecuador, Bolivia and Brazil. |

| Bactris gasipaes | Colombia | Pacific Colombian coast | Choo et al., 2009; Deloya & Gasca, 2018; Pardo-Locarno et al., 2005; Pardo-Locarno et al., 2019 | Chontaduro palm | Bolivia, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador and Panama. |

| Brahea dulcis | Mexico | Chochonteca in the Cañada region in Oaxaca; Reserva de la Biosfera Tehuacán-Cuicatlán Oaxaca | Conafor, 2020; Conanp, 2015; Zaragoza-Caballero et al., 2015 | Mexican sweet palm, soyale or soyale palm | From Mexico to Peru |

| Cocos botryophora, C. coronata, C. nucifera | Colombia, Puerto Rico | Colombian western regions, Mayagüez | Vaurie,1970a; Eberhard,1983; Franqui-Rivera et al., 2003; Vergara-Navarro et al., 2021 | Coconut palm | Pantropical |

| Elaeis guineensis | Ecuador, Costa Rica | La Loja; Quepos and Parrita | De la Pava et al., 2020; Lanteri et al., 2002; Vaurie, 1970a; Vergara-Navarro et al., 2021 | Oil palm | Tropical Africa; grown in the tropics. |

| Euterpe oleraceae | Venezuela | N/D | Choo et al., 2009 | Huasaí, huasaí palm | Northern Brazil, French Guiana, Suriname, Guyana, Peru, Bolivia, in Esmeraldas north of Ecuador, Venezuela, eastern Panama, Magdalena Medio and the Pacific and Amazon regions in Colombia |

| Mauritia flexuosa | Venezuela, Peru | N/D, Peruvian Amazone | Choo et al., 2009; Van Itterbeeck & Van Huis, 2012; | Moriche, moriche palm | Wide distribution in central and northern South America: Ecuador, Bolivia, Brazil, Peru, Colombia, Guyana, Venezuela, Suriname, Trinidad and Tobago |

| Oenocarpa bacaba | Venezuela | Venezuelan Amazon | Choo et al., 2009 | Milpesillo | Guyana from Colombia to Brazil |

| Syagrus romanzoffiana. S. schizophylla | Brazil | Alto Paraná ecoregion (Paranaense Forest) | Vaurie, 1970a; Araujo et al., 2018 | feathery coconut | It is native to southern Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay, and the Argentine coast. |

The infestation in gregarious palms, where damage spreads from a focal plant to adjacent individuals, mirrors the patch-level mortality reported in R. ferrugineus outbreaks in date palm plantations (Faleiro, 2006). Such localized dispersal may be driven by the physical proximity of palm stems, facilitating rapid expansion of infestations. In solitary palms, R. barbirostris was also observed attacking lateral shoots, indicating behavioral plasticity in selecting entry points. This opportunistic colonization strategy parallels that of Metamasius spp., which infest both primary stems and secondary shoots of diverse palm hosts (Weissling & Giblin-Davis, 1993).

The sequential progression of damage beginning with clean perforations indicative of recent oviposition or adult feeding, followed by multiple boreholes in advanced infestations, is consistent with the biology of other palm weevils. In R. ferrugineus, for example, early stages can only be detected through discrete entry holes or frass deposits, whereas advanced infestations produce widespread internal tunneling and crown collapse (Dembilio & Jacas, 2011). Similarly, in R. palmarum, larval feeding not only destroys host tissues but also facilitates the transmission of the nematode Bursaphelenchus cocophilus, the causal agent of red ring disease in coconut (Griffith, 1987). Although no pathogen association was observed in R. barbirostris, the fermentative odors and resin exudation recorded in this study are comparable to the secondary microbial colonization often reported in palms infested by Rhynchophorus.

The consistent presence of Zopherus spp. in highly degraded tissues further illustrates a successional process in which secondary insects exploit the conditions created by the primary borer. Comparable saproxylic successions have been reported in palms infested by species of Metamasius and Rhynchophorus, where decomposing tissues become niches for secondary beetles and fungi (Howard et al., 2001). This suggests that R. barbirostris not only functions as a primary pest but also plays a role in structuring arthropod communities associated with decaying palms.

The variables reported here, including perforation height, diameter, and number quantify the magnitude of damage and confirm that both larvae and adults actively contribute to palm mortality. In other palm weevils, similar diagnostic metrics (e.g., size of entry holes, pattern of galleries, crown symptoms) have been used as reliable indicators for early detection and management (Faleiro, 2006; Fiaboe et al., 2012). The construction of fresh soil mounds at the base of infested palms, recorded in this study, represents an additional diagnostic feature that could be incorporated into monitoring protocols, much like the frass deposits and oozing exudates used to detect R. ferrugineus.

Our findings indicate that R. barbirostris shares several biological and behavioral traits with major palm pests worldwide, such as Rhynchophorus ferrugineus, R. palmarum, and Metamasius spp. Its ability to establish overlapping generations, exploit multiple host tissues, and spread among neighboring palms underscores its potential as a pest of both ecological and economic concern. These parallels suggest that management strategies developed for other palm weevils such as pheromone trapping, sanitary removal of infested material, and cultural practices to reduce breeding sites, may serve as a useful foundation for developing targeted monitoring and control measures for R. barbirostris in Mexico.

Distribution and records. The geographical distribution of R. barbirostris from the lowlands of the Mexican Transition Zone (MTZ) to South America aligns with the classic Neotropical cenocron (Morrone, 2019). Its ecological niche characteristics, particularly temperature as a key environmental factor and its large amplitude, are also congruent with this pattern (Lizardo et al., 2025). This congruence supports the idea that cenocrons, as proposed by the MTZ theory, serve as evolutionary and ecological hypotheses. From these hypotheses, it is possible to make predictions about the ecological niches of species in relation to their patterns of richness and geographical distribution (Lizardo et al., 2025).

All records from entomological collections and databases allowed us to delimit the geographic distribution of R. barbirostris and suggested activity patterns throughout the year, although it is recognized that these data, not obtained from field observations, may present sampling biases. The higher frequency of records at certain times of the year (March to December 2007-2023), as reported in our findings, could be due to historical collecting efforts rather than the inherent biological activity of the species. However, when comparing these results with the existing literature, we found some similarities. For example, Sarwar (2016) reported the presence of weevil pupae (Rhyncophorus palmarum) in infested palms during May and August, which aligns with the end of the activity window observed in our records. Similarly, Jaramillo-Vivanco’s (2023) fieldwork in Ecuador, conducted between March and December, coincides with the period when our records were most abundant. Unlike what has been documented for other insect groups, such as the genus Ocoaxo, which presents a marked seasonality and synchronizes its life cycle with the rainy season (Cid-Muñoz et al., 2020), our data do not allow us to confirm a similar biological pattern for R. barbirostris. The temporal analysis of the records of these insects suggests that they have a univoltine life cycle, since all the collection data were restricted to 4 months of the year, from the beginning of summer in May, until the beginning of Autumn in October, a period that corresponds to the season of greatest rainfall in Mexico.

The preference of these beetles for freshly fallen trunks, as noted by Eberhard (1983) on a palm trunk in May, could explain why specimen collection is higher in certain months. The presence of the species is strongly linked to resource availability, as found in the fieldwork of López-Zent and Zent (2020), who, over 21 months of direct observation, were able to document the species ecology over time. Their observations, obtained directly from fieldwork, complement and contrast our findings based on historical data. Although our records reflect an apparent peak in activity, it is crucial to consider that ecological context and collection patterns can influence data availability. This integration of historical data and field observations, such as those of the authors, is essential to a more complete and accurate understanding of the biology and ecology of R. barbirostris. Our data point to a concentration of activity, suggesting that this apparent periodicity could be, at least in part, a reflection of historical data collection methods, rather than a strictly biological pattern. For example, some studies indicate that this type of bias can influence the interpretation of distribution patterns and seasonality (Elith et al., 2006; Fourcade et al., 2014). It is inferred that the presence or absence of the species is linked to specific ecological factors, such as the type of ecosystem or the food sources of the adults, which require further field research in order to confirm. The analysis of these data allowed the formulation of assumptions about the spatial distribution and the estimation of the geographical limits of their sightings, as well as the identification of areas suitable for their surveillance.

Accurate taxonomic identification is critical for modeling species distributions (Elith et al., 2006; Elith & Leathwick, 2009; Pearman et al., 2010). Although the taxonomic history of the bearded weevil does not present the ambiguities common in other phytophagous insects, such as the bark beetles (Armendáriz-Toledano et al., 2014a, b; Valerio-Mendoza et al., 2019) of the genus Dendroctonus or the spittlebugs of the genus Ocoaxo (Armendáriz-Toledano et al., 2023; Castro-Valderrama et al., 2017, 2019; Cid-Muñoz et al., 2022), extensive record validation was performed to ensure the reliability of our data. To do so, we reviewed records and specimens from several key entomological collections in Mexico. The identification of each specimen was validated through its external morphological characteristics, allowing us to confirm the species. These findings were consistent with the descriptions and taxonomic keys of Vaurie (1970a, 1970b) and Morrone & Cuevas (2002), which served as the final validation criterion. The review of 506 specimens, representing 31.9% of the total records through 2023, revealed no inconsistencies, demonstrating accurate identifications of R. barbirostris throughout its distribution. This validation confirms that our model is based on taxonomically accurate data and supported by physical material, which strengthens the reliability of our conclusions about the species’ distribution.

Based on the above, and even though the taxon R. barbirostris was originally described by Fabricius (1775) and its formal name, as we know it today, has been in use since 1815, when the genus was established. This means that the species has maintained its nomenclatural stability for more than 2 centuries. This consistency over time is a critical factor, as its identification does not present significant problems, thereby reducing uncertainty in historical and recent records. This stability is largely attributed to the meticulous work of specialists, who have generated a series of reliable and consistent records over time (Alonso-Zaragaza et al., 1999; Jones et al., 2008; Morrone, 2014; Morrone & Cuevas, 2002, 2009; Oberprieler et al., 2007; Rafinesque, 1815; Vaurie, 1970a, b).

Since its first record in Veracruz in the 1910´s, approximately 400 records of R. barbirostris have been compiled in Mexico from entomological collections and online databases. The oldest records show a widespread geographic distribution, with presence in multiple states, including Baja California, Chiapas, Jalisco, Oaxaca, Quintana Roo, Sinaloa, and Veracruz. In recent years, new records have focused on a subset of these states. In 2006, it was revealed that concentrated infestations in a smaller area, particularly in the 9 communities sampled in this study, corresponding to the Chochonteca region and the agricultural zones of the Tehuacán-Cuicatlán Biosphere Reserve in Oaxaca, where an average number of 20 individuals per palm infested by the bearded weevil was reported. This localized concentration suggests a possible local adaptation of R. barbirostris to the environmental conditions and to the specific populations of Brahea dulcis in this region (Conafor 2020, 2023; Conanp, 2023). However, focused monitoring in these affected areas may have introduced sampling bias, potentially overlooking other regions where the species may also be present. The bearded palm weevil causes significant damage to its host plant, affecting the stipe and foliage, which can lead to its death. This damage impacts communities that depend on the B. dulcis palm for handicrafts and as a source of income (Pavón et al., 2006; Pérez-Valladares et al., 2020). As with the palm weevil Rhynchophorus palmarum, which is a disease vector and causes bud rot, the difficulty in controlling these pests has led to similar phytosanitary strategies. In the case of R. palmarum, high populations hamper plantation renewal (Aldana-de la Torre et al., 2011; Giblin-Davis et al., 1997). In both cases, traditional management strategies have recommended drastic control measures such as cutting and burning infested plants to eliminate the source of infestation (Wattanapongsiri, 1966). The discovery of Zopheridae specimens in infested B. dulcis palms suggests their role as secondary organisms in the decomposition process. Unlike weevils, which are often primary invaders of healthy or slightly weakened plant tissue, Zopheridae are typically associated with decaying wood or degraded plant tissue. Based on this, it is plausible that the activity of the bearded weevil, by drilling into the trunk and weakening the tissue, creates the favorable conditions for Zopheridae to colonize the palms. Therefore, the presence of these beetles does not indicate a primary infestation, but rather an advanced state of host deterioration, which reinforces the severity of the damage caused by the bearded weevil (Cebeci et al., 2018; Pezzi et al., 2022).

Adult bearded weevils have been recorded on 15 species of palm trees: Attalea funifera, A. maripa, A. pindobossu, A. piassabossu, Bactris gasipaes, Brahea dulcis, Cocos botryophora, C. coronata, C. nucifera, Elaeis guineensis, Euterpe oleraceae, Mauritia flexuosa, Oenocarpa bacaba, Syagrus romanzoffiana, and S. schizophylla (Bukkens 1997; Choo 2009; Eberhard 1983). When comparing the number of records per host between different geographical sites corresponding to the distribution of R. barbirostris, it is notable that individuals from other geographical sites have a broader diet, compared to Mexican specimens (Choo 2009; Eberhard 1983; Vaurie 1970a).

Regarding other members of the Dryophthorinae subfamily, they are characterized by presenting phytophagy as a feeding habit (Oberprieler et al., 2007) and colonizing a wide variety of hosts. The subfamily of these insects, although notable for its wide distribution in diverse monocotyledons with reports of infestations in grasses, sedges, orchids, and bromeliads in different biomes (Anderson, 2002; Bautista-Gallardo et al., 2020; Oberprielier et al., 2007), has been predominantly documented in association with palms of the genera mentioned here (Morrone, 2009, 2014). Although their role as agriculturally important pests is globally recognized (De la Pava et al., 2020; Sepulveda-Cano & Rubio-Gómez, 2009), this specificity in host choice in the context of palms not only justifies but also strengthens the relevance of our study by focusing attention on 1 of the most significant interactions for this subfamily.

In summary, the analysis of the geographic and potential distribution of R. barbirostris in Mexico revealed the phenotypic plasticity of the species, which can be inferred from its ability to thrive in a variety of biomes, from humid montane forests to dry tropical forests. Although current records are limited to certain areas, potential distribution models suggest that the palm weevil finds favorable environmental conditions in a large part of the national territory. The exploration of all available records for this taxon has not only contributed to identifying sites with ideal conditions for its presence but also underscores the need for monitoring and verification sampling to confirm these predictions. These findings support and suggest the inclusion of the palm weevil in the Mexican Official Standard.

Acknowledgements

We thank Fernando Reyes Flores, Director of Reserva de la Biosfera Tehuacán-Cuicatlán, Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas Dirección and the following institutions for funding this research: PAPIIT-UNAM (IN223924) and Secretaría de Ciencias, Humanidades, Tecnología e Innovación (SECIHTI). O.VM. is a postdoctoral fellowship from SECIHTI at Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, Campus Linares. Francisco Armendáriz-Toledano and Gerardo Cuéllar-Rodríguez are members of Sistema Nacional de Investigadores-SECIHTI. We also thank Mauricio Ramírez Hernández for the photographs of R. barbirostris.

References

Abraham, V. A., Al-Shuaibi, M. A., Faleiro, J. R., Abozuhairahand, R. A., & Vidyasagar, P. S. P. V. (1998). An integrated management approach for red palm weevil, Rhynchophorus ferrugineus Oliv., a key pest of date palm in the Middle East. Journal of Agricultural and Marine Sciences, 3, 77–83. https://doi.org/10.24200/jams.vol3iss1pp77-83

Aiello-Lammens, M. E., Boria, R. A., Radosavljevic, A., Vilela, B., & Anderson, R. P. (2015). spThin: An R package for spatial thinning of species occurrence records for use in ecological niche models. Ecography, 38, 541-545. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.01132

Aldana- De la Torre, R. C., Aldana-De la Torre, J. A., & Mauricio-Moya, O. (2011). Manejo del picudo Rhyncophorus palmarum L. Publicación del Centro de Investigación en palma de aceite Cenipalma, realizada con fondos provenientes del Convenio 20110059 suscrito entre el Ministerio de Agricultura y Desarrollo Rural y el Instituto Colombiano Agropecuario, ICA. http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12324/19497

Alonso-Zaragaza, M. A., & Lyal, C. H. C. (1999). A world catalogue of families and genera of Curculionoidea (Insecta: Coleoptera) (excluding Scolytidae and Platypodidae). Entomopraxis. Barcelona.

Anderson, R. S. (2002). Chapter 131. Curculionidae. In R. H. Jr. Arnett, M. C. Thomas, Skelley P. E., & J. H. Frank (Eds.), American beetles. Volume II: Polyphaga: Scarabaeoidea through Curculionoidea (pp. 722–815) Boca Raton: CRC Press. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781420041231

Anderson, R. S. & Marvaldi, A. E. (2014). Dryophthorinae Schoenherr, 1825. In R. A. B. Les-chen, & R. G. Beutel (Eds.), Handbook of Zoology, Arthropoda: Insecta: Coleoptera Volume3: morphology and systematics (Phytophaga) (pp. 477–487). Berlin: De Gruyter.

Araujo, J. J., Keller, H. A., & Hilgert, N. I. (2018). Management of pindo palm (Syagrus romanzoffiana Arecaceae) in rearing of Coleoptera edible larvae by the Guarani of northeastern Argentina. Ethnobiology and Conservation, 7, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.15451/ec2018-01-7.01-1-18

Armendáriz-Toledano, F., López-Posadas, M. A., Utrera-Vélez, Y., Romero-Nápoles, J. R., & Castro-Valderrama, U. (2023). More than 80 years without new taxa: analysis of morphological variation among members of Mexican Aeneolamia Fennah (Hemiptera, Cercopidae) support a new species in the genus. Zookeys, 1139, 71–106. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.1139.85270

Armendáriz-Toledano, F., Niño-Domínguez, A., Macías-Sámano, J., & Zúñiga, G. (2014b). Review of the geographical distribution of Dendroctonus vitei (Curculionidae: Scolytinae) based on geometric morphometrics of the seminal rod. Annals of the Entomological Society of America, 107, 748–75. https://doi.org/10.1603/AN13176

Armendáriz-Toledano, F., Niño-Domínguez, A., Sullivan, B. T., Macías-Sámano, J., Víctor, J., Clarke, S. et al. (2014a).

Two species within Dendroctonus frontalis (Coleoptera: Curculionidae): evidence from morphological, karyological, molecular, and crossing studies. Annals of

the Entomological Society of America,107, 11–27. https://doi.org/10.1603/AN13047

Boria, R. A., Olson, L. E., Goodman, S. M., & Anderson, R. P. (2014). Spatial filtering to reduce sampling bias can improve the performance of ecological niche models. Ecological Modelling, 275, 73–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2013.12.012

Bouchard, P. (2014). The book of beetles. A life size-guide to six hundreds of nature’s gems. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Brown, J. H. (1984). On the relationship between abundance and distribution of species. The American Naturalist, 124, 255–279. https://doi.org/10.1086/284267

Bukkens, S. G. F. (1997). The nutritional value of edible insects. Ecology of Food and Nutrition, 36, 287–319.

https://doi.org/10.1080/03670244.1997.9991521

Carretero, M. A., & Sillero, N. (2016). Evaluating how species niche modelling is affected by partial distributions with an empirical case. Acta Oecologica, 77, 207–216. https:

//doi.org/10.1016/j.actao.2016.08.014

Castro-Valderrama, U., Carvalho, G. S., Peck, D. C., Valdez-Carrasco, J. M., & Romero, J. N. (2019). Two new species of the spittlebug genus Ocoaxo Fennah (Hemiptera: Cercopidae) from Mexico, and keys for the groups, group three, and first subgroup. Neotropical Entomology, 48, 260–268. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13744-018-0629-0

Castro-Valderrama, U., Romero-Nápoles, J., Peck, D. C., Valdez-Carrasco, J. M., Llanderal-Cázares, C., Bravo-Mojica, H. et al. (2017). First report of spittlebug species (Hemiptera: Cercopidae) associated with Pinus species (Pinaceae) in Mexico. Florida Entomologist, 100, 206–208. https://doi.org/10.1653/024.100.0136

Cebeci, H. H., & Baydemir, M. (2018). Predators of bark beetles (Coleoptera) in the Balikesir region of Turkey. Revista Colombiana de Entomología, 44, 283–287. https://doi.org/10.25100/socolen.v44i2.7326

Champion, G. C. (1909-1911). Insecta, Coleoptera, Rhynchophora, Curculionidae, Curculioninae, (concluded) and Calandrinae. In R. H. Porter (Eds.), Biologia Centrali-Americana. Vol. IV (pp. 1–213). London: The Thomas Lincoln Casey Library.

Choo, J., Zent, E. L., & Simpson, B. B. (2009). The importance of traditional ecological knowledge for palm-weevil cultivation in the Venezuelan Amazon. Journal of Ethnobiology, 29, 113–128. https://doi.org/10.2993/0278-0771-29.1.113

Cid-Muñoz, R., Cervantes-Espinoza, M., Castro-Valderrama, U., Cuéllar-Rodríguez, G., Cibrián-Tovar, D., & Armendáriz-Toledano, F. (2022). Pasado y presente de los salivazos del complejo Ocoaxo de los pinos (Hemiptera: Cercopidae): Distribución espacial y temporal. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 93, e934130. https://doi.org/10.22201/ib.20078706e.2022.93.4130

Conafor (Comisión Nacional Forestal). (2020). Diagnóstico fitosanitario del estado de Oaxaca, primer semestre, año 2020. Gerencia Estatal, Oaxaca.

Conafor (Comisión Nacional Forestal). (2023). Programa Operativo de Sanidad Forestal 2023 del Estado de Oaxaca. Comité de Sanidad Forestal, Estado de México, México.

Conanp (Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas). (2013). Programa de Manejo Reserva de la Biosfera Tehuacán-Cuicatlán. Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (Semarnat). México D.F.

Conanp (Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas). (2015). Reporte de presencia de Rhinostomus barbirostris en núcleos agrarios dentro de las Reserva de la Biosfera Tehuacán Cuicatlán. México D.F.

De la Pava, N., García, M. A., Brochero, C. E., & Sepúlveda-Cano, P. (2019). Registros de Dryophthorinae (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) de la costa Caribe Colombiana. Acta Biológica Colombiana, 25, 96–103. https://doi.org/10.15446/abc.v25n1.77797

Dembilio, Ó., & Jacas, J. A. (2011). Life cycle of the invasive Red Palm Weevil, Rhynchophorus ferrugineus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae), in Phoenix canariensis under Mediterranean climate. Bulletin of Entomological Research, 101, 153–163. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007485310000283

Eberhard, W. G. (1983). Behavior of adult bottle brush weevils (Rhinostomus barbirostris) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Revista de Biología Tropical, 31, 233–244. https://doi.org/10.15517/rbt.v31i2.24986

Elith, J., Graham, C. H., Anderson, R. P., Dudík, M., Ferrier, S., Guisan, A. et al. (2006). Novel methods improve prediction of species distributions from occurrence data. Ecography, 29, 129–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2006.0906-7590.04596

Elith, J., & Leathwick, J. R. (2009). Species distribution models: ecological explanation and prediction across space and time. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 40, 677–697. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.110308.120159

Elith, J., Phillips, S. J., Hastie, T., Dudík, M., Chee, Y. E., & Yates, C. J. (2011). A statistical explanation of MaxEnt for ecologists. Diversity and Distributions, 17, 43–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1472-4642.2010.00725

Faleiro, J. R. (2006). A review of the issues and management of the red palm weevil Rhynchophorus ferrugineus (Coleoptera: Rhynchophoridae) in coconut and date palm during the last one hundred years. International Journal of Tropical Insect Science, 26, 135–154. https://doi.org/10.1079/IJT2006113

FAO. (2013). Edible insects. Future prospects for food and feed security. FAO. Rome.

Ferreira, J. M. S. (2008). Manejo integrado de pragas docoqueiro. Ciência Agrícola, 8, 21–29.

Ferreira, J. M. S., Fontes, R. H., & Procopio, S. O. (2007). Resinose do coqueiro: como identificar e manejar. Aracaju: Embrapa Tabuleiros Costeiros.

Fiaboe, K. K. M., Peterson, A. T., Kairo, M. T. K., & Roda, A. L. (2012). Predicting the potential worldwide distribution of the red palm weevil Rhynchophorus ferrugineus (Olivier) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) using ecological niche modeling. Florida Entomologist, 95, 559–673. https://doi.org/10.1653/024.095.0317

Fick, S. E. & Hijmans, R. J. (2017). WorldClim 2: new 1-km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. International Journal of Climatology, 37, 4302–4315. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.5086

Fourcade, Y., Engler, J. O., Rödder, D., & Secondi, J. (2014). Mapping species distributions with MAXENT using a geographically biased sample of presence data: A performance assessment of methods for correcting sampling bias. Plos One, 9, e97122. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0097122

Franco, E. (1964). Estudo sobre o Anel Vermelho do Coqueiro. Departamento de Defesa e Inspeção Agropecuária. Sergipe: Serviço de defesa sanitária vegetal. Inspetoria de defesa sanitária vegetal.

Franqui-Rivera, R., & Medina-Gaud, S. (2003). Identificación de insectos de posible introducción a Puerto Rico. San Juan: Departamento de Agricultura de Puerto Rico/ Universidad de Puerto Rico.

Gardner, J. C. M. (1934). Immature stages of Indian Coleoptera (14) (Curculionidae). Indian Forest Records, 20, 1–48.

Gardner. J. C. M. (1938). Immature stages of Indian Coleoptera (24 Curculionidae Contd.). Indian Forest Records, Entomology Series, 3, 227–261.

GBIF.org. (2023). GBIF Occurrence Download. https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.45tpj3

Giblin-Davis, R. M., Gries, R., Gries, G., Peña-Rojas, E., Pinzon, I., Peña, J. E. et al. (1997). Aggregation pheromone of the palm weevil, Dynamis borassi (F.) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Journal of Chemical Ecology, 23, 2287–2297. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOEC.0000006674.64858.f2

Goodey, T. (1933). Plant parasitic nematodes and the diseases they cause, with a foreword by R.T. Leiper. London: E.P. Dutton and Co.

Goodey, J. B. (1960). Rhadinaphelenchus cocophilus (Cobb 1919) n. comb, the nematode associated with ‘red ring’ disease of coconuts. Nematologica, 5, 98–102.

Google (2020). Google Earth Sofware libre Versión 9.140.0. http://earth.google.com/

Grebennikov, V. V. (2018a). Dryophthorinae weevils (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) of the forest floor in Southeast Asia: illustrated overview of nominal Stromboscerini genera. Zootaxa, 4418, 121–135. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4418.2.2