Población panmíctica de la polilla polinizadora Tegeticula baja (Lepidoptera: Prodoxidae) a lo largo de la distribución de sus plantas hospederas

Maria Clara Arteaga a, *, C. Rocio Alamo-Herrera a, Anna Darlene van der Heiden a, b, Nicole Sicaeros-Samaniego a

a Centro de Investigación Científica y de Educación Superior de Ensenada, Departamento de Biología de la Conservación,

Carr. Tijuana-Ensenada 3918, Zona Playitas, 22860 Ensenada, Baja California, Mexico

b Uppsala University, Department of Medical Biochemistry and Microbiology, Hursagatan 3, 752 37, Uppsala, Sweden

*Corresponding author: arteaga@cicese.mx (M.C. Arteaga)

Received: 14 March 2025; accepted: 24 July 2025

Abstract

Ecological interactions and demographic history shape the genetic diversity of populations. Tegeticula baja is the specialist pollinator of different Yucca hosts in the Baja California Peninsula, a region that experienced changes in habitat distribution during the Pleistocene. To assess the effects of host specificity and historical changes in habitat configuration, we i) analyzed the genetic structure of moth populations associated with 3 different Yucca plant species, ii) identified signatures of historical demographic changes, and iii) reconstructed the past potential distribution of T. baja at different periods. We genotyped the COI of 128 moths from 39 locations and estimated genetic diversity, population structure, and demographic history. We found an overall haplotype diversity of 0.708 and a nucleotide diversity of 0.0015. Moth populations associated with the 3 hosts exhibited similar diversity levels, with no evidence of genetic structure. These findings suggest that ecological associations with different host plants do not drive T. baja diversification. Instead, its demographic history has played a more significant role in shaping the levels and the distribution of the genetic diversity.

Keywords: Ecological interaction; Genetic diversity; Historical demography; Insect-plant association; Population structure; Yucca

Resumen

Las interacciones ecológicas y la historia demográfica moldean la diversidad genética de las poblaciones. Tegeticula baja es una polinizadora especialista de diferentes yuccas hospederas en la península de Baja California, una región que experimentó cambios en la distribución de los hábitats durante el Pleistoceno. Para evaluar los efectos de la especificidad del huésped y los cambios históricos en la configuración de los hábitats, i) analizamos la estructura genética de las poblaciones de polillas asociadas a distintos hospederos, ii) identificamos señales de cambios demográficos históricos y iii) reconstruimos su distribución potencial en el pasado. Genotipificamos el COI de 128 polillas de 39 localidades y estimamos la diversidad genética, la estructura poblacional y la historia demográfica. Encontramos una diversidad haplotípica global de 0.708 y una diversidad nucleotídica de 0.0015. Las poblaciones de polillas asociadas a las 3 especies de plantas mostraron niveles de diversidad similares, sin evidencia de estructura genética. Estos hallazgos sugieren que la asociación ecológica con diferentes plantas huésped no impulsa la diversificación de T. baja. En cambio, su historia demográfica ha desempeñado un papel más importante en la configuración de su diversidad genética.

Palabras clave: Interacciones ecológicas; Diversidad genética; Historia demográfica; Asociación planta-insecto; Estructura poblacional; Yucca

Introduction

The ecological interaction between pollinator insects and their host plants plays a crucial role in shaping the distribution and genetic diversity of the species involved, influencing processes such as natural selection, genetic drift, and gene flow among populations (Futuyma, 2000; Gloss et al., 2013, 2016). Additionally, other factors, such as geographic distance (e.g., Driscoe et al., 2019) and demographic history shaped by past climatic changes (e.g., Liu et al., 2016; Smith et al., 2011), can influence the amount of genetic variation within populations and its spatial distribution.

Moths of the genus Tegeticula Zeller are specialist pollinators of the genus Yucca Linnaeus, maintaining an obligate mutualism (Engelmann, 1872; Pellmyr, 2003). Generally, each Tegeticula species pollinates a single Yucca species. However, few moth species pollinate multiple Yucca species (Althoff et al., 2006, 2012). During the flowering period, adult moths emerge and mate within Yucca flowers. The female uses specialized mouthparts to collect pollen and transfer it to other flowers. Upon arrival, she inserts her ovipositor into the ovary to lay her eggs. After, she deposits the pollen onto the flower’s stigma, ensuring fertilization and fruit development, from which the larvae will feed on a small portion of the seeds (Engelmann, 1872; Pellmyr, 2003). This obligate interaction between yucca and yucca moths influences the gene flow, facilitating differentiation and diversification processes in both pollinators and host plants (Arteaga et al., 2020; Leebens-Mack & Pellmyr, 2004; Leebens-Mack et al., 1998)

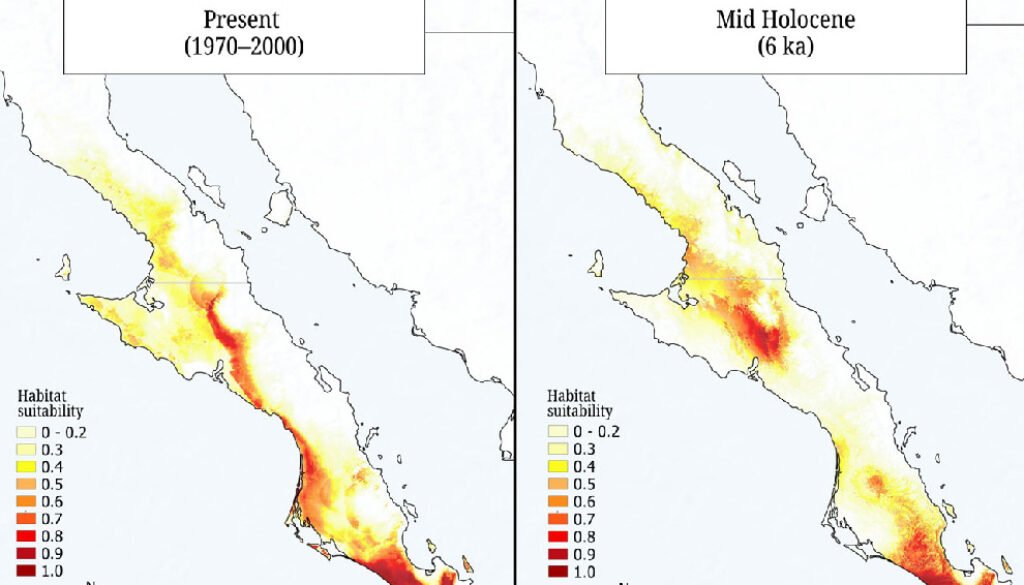

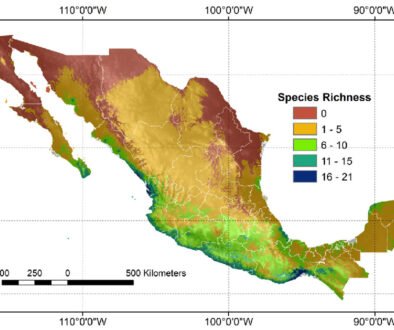

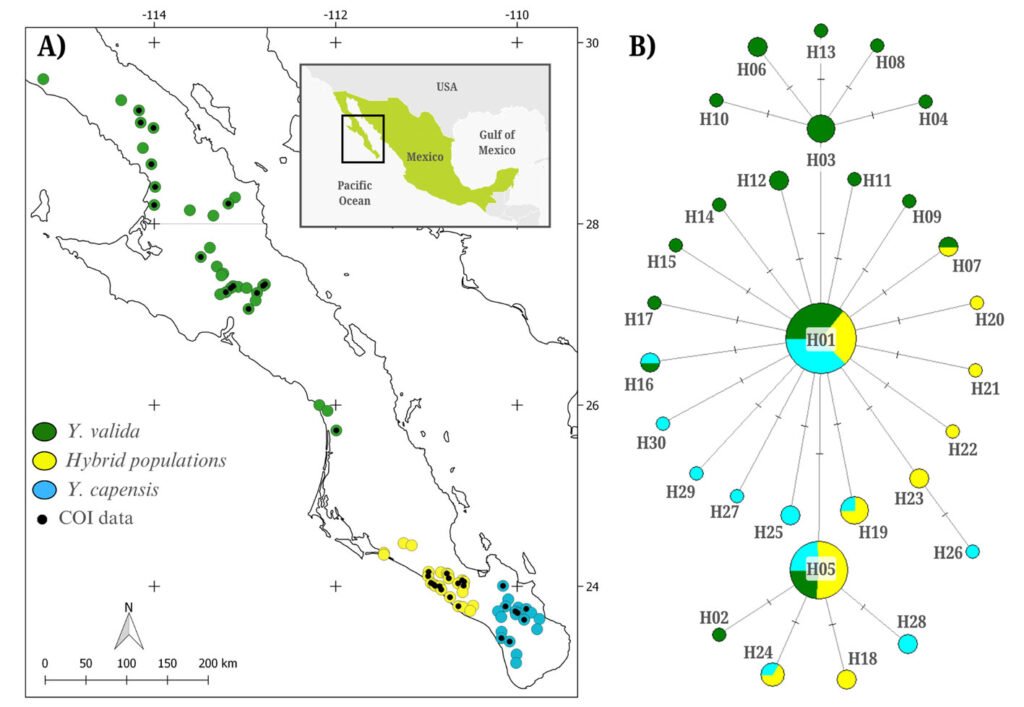

Yucca plants and yucca moths are distributed across North America (Pellmyr et al., 2008). This region has experienced changes in habitat distribution due to Pleistocene climatic fluctuations, which have impacted the genetic diversity and structure of both Yucca populations and their pollinators (Alemán et al., 2024; Arteaga et al., 2020; De la Rosa et al., 2020; Smith et al., 2011). In the Baja California Peninsula (BCP), Mexico, Tegeticula baja Pellmyr is an endemic moth species distributed from the central to the southern part of the peninsula. This moth pollinates 2 endemic Yucca species and their hybrid populations, which exhibit an allopatric distribution: Yucca valida Brandegee occurs in the arid ecosystems of the Central Desert and the northern Magdalena Plains, hybrid populations are found in the southern Magdalena Plains (Arteaga et al., 2020), and Y. capensis Lenz is located in the tropical dry forest of southern BCP (Lenz, 1998; Pellmyr et al., 2008; Turner et al., 1995).

The flowering phenology of these endemic Yucca species and their hybrid populations is asynchronous and influenced by water availability. Yucca valida blooms from April to July (Turner et al., 1995), hybrid populations flower in August and September, and Y. capensis blooms from September to October (Arteaga et al., 2015; Lenz, 1998). The asynchronous flowering limits the temporal coexistence of moths from different populations, as each group responds to the floral signals of its host plant. Additionally, these moths exhibit short-distance dispersal (Álamo-Herrera et al., 2022). Consequently, the temporal availability of floral resources and the limited dispersal of these pollinators may contribute to genetic structuring among populations across their distribution.

Given the obligate interaction between pollinators and plants, we hypothesize that distinct genetic lineages of T. baja are associated with each host Yucca species, influenced by geographic distances and asynchronous flowering. Additionally, considering historical habitat changes in the BCP (Dolby et al., 2015), we expect an impact on the species’ demographic history. Specifically, we i) examined the genetic structure among moth populations associated with each Yucca species and their hybrids, ii) identified signals of historical population changes, and iii) determined how the distribution of suitable conditions for the species has changed over time. This study will contribute to a better understanding of how ecological interactions and historical environmental changes shape the genetic diversity of pollinating moths in the Yucca-Tegeticula mutualism.

Materials and methods

We visited 75 localities where the endemic yuccas and their hybrids were found (Fig. 1A). We collected 3 to 5 fruits from at least 5 plants per locality. We dissected the fruits and examined them for the presence of T. baja larvae, which are typically found among the seeds. We stored the larvae in 96% ethanol and preserved them at -80 °C. We collected a total of 128 moth larvae from 39 of the 75 localities (Fig. 1A), including 16 sites of Yucca valida (N = 49), 8 of Y. capensis (N = 39), and 15 of hybrid plants (N = 40).

We used 20 mg of larval tissue for DNA extraction following the commercial kit “Qiagen DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit” protocol. We amplified a fragment of the Cytochrome Oxidase subunit I (COI) marker using primers S1461 (5’-ACAATTTATCGCCTAAACTTCAGCC-3’) and A2302 (5’-CTACAAATCCTAATAATCCATTG-3’; Smith et al., 2009). The PCR mixture consisted of 5 μl of buffer (1X), 2 μl of MgCl (2 mM), 0.4 μl of dNTPs (0.6 mM), 0.2 μl of Taq polymerase (1U), 1 μl of each primer (0.4 mM each), 3 μl of DNA, and 12.4 μl of molecular-grade water, for a total reaction volume of 25 μl. Thermocycler conditions were: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min, 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 48 °C for 45 s, extension at 72 °C for 1 min, and a final elongation at 72 °C for 1 min. We verified the amplification quality using 1% agarose gels. PCR products were sequenced by SeqXcel (www.seqxcel.com). We also tested protocols for amplifying the nuclear EF1α gene and 9 nuclear microsatellites previously used in other species of the same genus (Drummond et al., 2010; Smith et al., 2008); however, amplifications were unsuccessful.

We visualized and edited COI sequences using MEGA X 4.0 and aligned them with MUSCLE (Tamura et al., 2007). We estimated the genetic diversity for the complete dataset and separately for individuals collected in locations from Y. valida, Y. capensis, and the hybrid Y. valida × Y. capensis using DNAsp (Rozas et al., 2003). We calculated the number of polymorphic sites (PS), number of haplotypes (H), haplotype diversity (h), and nucleotide diversity (π). To explore genealogical relationships, we constructed a haplotype network using the Median-Joining method in NETWORK 5.0 (Bandelt et al., 1999). Finally, to assess genetic structure among moths associated with different host plants, we implemented an analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) using Arlequin (Excoffier et al., 2005).

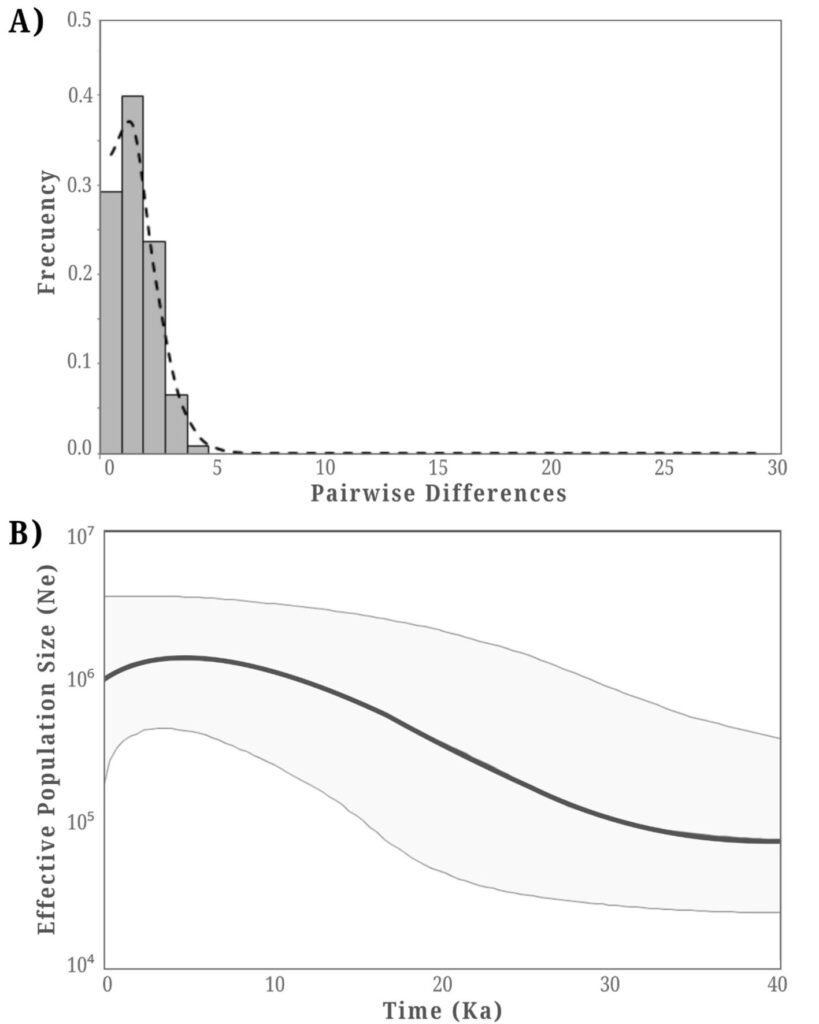

We assessed the demographic history of T. baja using 3 methods. First, we conducted Tajima’s D test using DNAsp (Rozas et al., 2003). Negative values indicate population expansion, while positive values suggest population reduction (Nakamura et al., 2018). Second, we performed a mismatch distribution analysis in Arlequin, where an unimodal distribution suggests population expansion, while a multimodal distribution indicates a stable population size (Rogers & Harpending, 1992). Finally, we conducted a Bayesian Skyline Plot (BSP) analysis (Drummond et al., 2005) using BEAST 2.6.0 (Bouckaert et al., 2014). As input data, we used the commonly reported nucleotide substitution rate for COI in arthropods (1.77% divergence per lineage per million years; Papadopoulou et al., 2010), a strict molecular clock, and the HKY substitution model defined in JmodelTest2 (Darriba et al., 2012). We ran 100 million steps, sampling every 10,000 generations in the MCMC method. We calculated the effective sample size (ESS) value and constructed the BSP using TRACER 1.7 (Rambaut et al., 2018).

Table 1

Genetic diversity of Tegeticula baja based on the mitochondrial COI marker. The table includes the host plant, sample size (N), number of polymorphic sites (PS), number of haplotypes (H), haplotype diversity (h), and nucleotide diversity (π).

| Host yucca plant | N | PS | H | h | π |

| Yucca valida | 49 | 14 | 17 | 0.733 | 0.0016 |

| Hybrid populations | 40 | 9 | 10 | 0.750 | 0.0015 |

| Yucca capensis | 39 | 11 | 11 | 0.617 | 0.0012 |

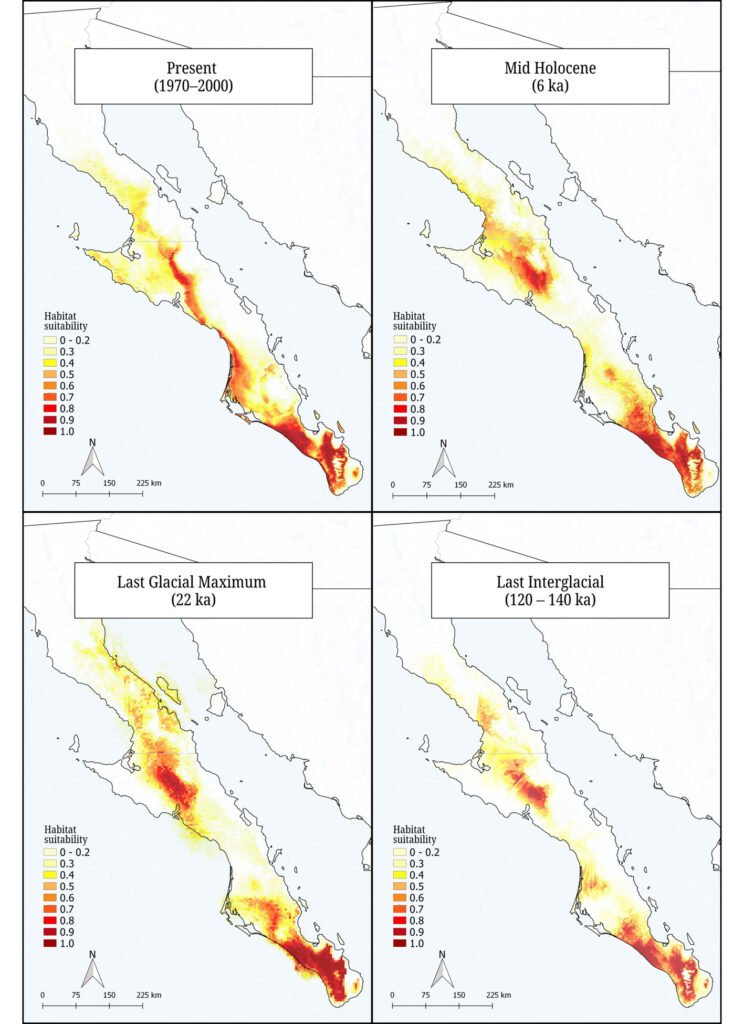

We built species distribution models to assess changes in the geographic distribution of suitable conditions for Tegeticula baja and to support the interpretation of its genetic diversity and demographic history estimates. We considered 4 time periods: present (years 1970-2000), mid-Holocene (6,000 years ago), Last Glacial Maximum (22,000 years ago), and Last Interglacial (120,000 – 140,000 years ago). We constructed the models using the 75 sampling points obtained in this study, the 19 bioclimatic variables from the WorldClim 2.1 database (Fick & Hijmans, 2017), and the MAXENT software (Phillips et al., 2006), with 80% of the data used for training and 20% for validation. We configured 2,000 iterations and 10 replicates. The model evaluation included the area under the curve (AUC) and binomial probabilities, where an AUC > 0.9 reflects excellent predictive capacity.

Results

The alignment of 128 sequences resulted in 767 bp with 27 polymorphic sites, defining 30 haplotypes (NCBI ID: PX127684-PX127713; Fig. 1B). The overall haplotype diversity was moderate (h = 0.708), and nucleotide diversity was low (π = 0.0015). Moth populations associated with the 3 host plants exhibited similar diversity levels (Table 1). The haplotype network indicated that haplotypes were closely related, and that the most abundant haplotype was widely distributed among the 3 moth populations pollinating different host plants (Fig. 1B). The AMOVA revealed that the variance among moths associated with different host plants was low and not significant (Fst = 0.011, p = 0.13). In contrast, most variation was found within populations.

Since no signs of genetic structure were detected, demographic analyses and niche modeling were conducted considering all individuals as a panmictic population. Demographic analyses provided evidence of a historical population expansion. Tajima’s D test showed significant negative values (D = -2.27970, p < 0.01), and the mismatch analysis distribution was unimodal (Fig. 2A). Consistently, the BSP analysis suggested a population expansion beginning approximately 25,000 years ago (Fig. 2B).

The species distribution models, with high predictive power (AUC > 0.9), revealed historical changes in the extent and distribution of environmentally suitable areas for T. baja (Fig. 3). During the Last Interglacial (120 ka), the distribution was limited to 2 areas, one in the central and other in the southern regions of the peninsula. During the Last Glacial Maximum (22 ka) and the mid-Holocene (6 ka), an expansion occurred in both regions. Finally, in the present period (1970-2000), the potential distribution of suitable conditions for these moths is observed to be continuously present along the western portion of the peninsula, connecting the central and southern regions.

Discussion

In the obligate mutualism between Yucca plants and Tegeticula moths, the distribution of feeding and oviposition resources provided by host plants determines the presence of moths in the landscape. In this study, we evaluated the genetic structure of Tegeticula baja populations associated with different Yucca species with allopatric distributions. Contrary to our expectations, we found a single panmictic population of pollinator moths throughout its geographic range. Additionally, we detected signals of historical demographic expansion. This suggests that the ecological association with different hosts is not driving the diversification of this species and that its historical demography has played a more relevant role in the distribution of its genetic diversity.

The genetic structure of a species is influenced by multiple factors, such as dispersal capacity, the intensity of ecological interactions, and the climatic history of the areas it inhabits (Driscoe et al., 2019; Futuyma, 2000; Smith et al., 2011). Specifically, T. baja has a limited dispersal distance per generation, and only 1 generation per year (~ 42 m; Álamo-Herrera et al., 2022); its host plants have a discontinuous distribution in the current landscape, and they also exhibit asynchronous flowering (Arteaga et al., 2020; Lenz, 1998; Turner et al., 1995). Together, these factors suggested that we could find genetic structure among moth populations associated with different Yucca species. However, we did not observe significant genetic differentiation. It is possible that the age of origin of its host plants and changes in the distribution of suitable habitat conditions could partially explain this pattern.

The divergence between the 2 endemic Yucca species of the BCP is estimated to have occurred approximately 500,000 years ago (Alemán et al., 2024). The formation of hybrid populations is even a more recent event, proposed to have occurred during the Pleistocene, around 21,000 years ago, when favorable climatic conditions allowed the co-occurrence of Y. valida and Y. capensis in the same region (Arteaga et al., 2020). This period of change in host plant distribution likely also influenced the distribution of the moth Tegeticula baja. Species distribution models and demographic analyses support this, indicating a population expansion beginning around 25,000 years ago, followed by a stabilization phase approximately 3,000 years ago. These historical changes in habitat configuration likely shaped the demographic history of the moth, reducing the potential for genetic divergence across its range due to alternating periods of population isolation and secondary contact. Although the current distribution of host plants is fragmented, the slow generational turnover of T. baja, with 1 generation per year, suggests that insufficient time has passed for genetic drift to produce detectable genetic structure.

The phylogeographic pattern of Tegeticula baja does not exhibit genetic structuring associated with host plant identity, which contrasts with that of other Tegeticula species, where genetic differentiation is correlated with either geographic distance or Yucca host species. For example, T. yucasella exhibits high genetic differentiation associated with geographic distance and interactions with different Yucca species (Leebens-Mack & Pellmyr, 2004). Similarly, T. maculata, the pollinator of Hesperoyucca Engelmann, exhibits genetic clades associated with the biogeographic history of its region (Althoff et al., 2007; Segraves & Pellmyr, 2001). Although all these studies, including ours, used the same mitochondrial marker (COI subunit), we did not detect genetic differentiation in our samples. These differences between our findings and previous reports may be related to the spatial scale, which is much larger in the study of T. yucasella, and to the time of origin and biogeographic history of the host plants in the case of T. maculata (Segraves & Pellmyr, 2001).

The levels of genetic diversity detected in the panmictic population of T. baja were moderate. In particular, moths associated with Y. valida exhibited a higher number of haplotypes, possibly due to their larger geographic range (Fig. 1A). The overall nucleotide diversity was low (π = 0.0015), falling below values reported for other species in the genus, such as T. antithetica and T. synthetica (π = 0.004 and 0.005, respectively; Smith et al., 2008). This pattern of low genetic diversity observed in T. baja may be related to the historical demographic growth detected in this species. A similar pattern was reported in the panmictic population of the parasitoid wasp Digonogastra sp., which interacts with 2 Tegeticula species in the BCP (π = 0.002; Álamo-Herrera et al., 2024). This supports the idea that the levels and distribution of genetic variation in these moths are more related to their historical demography than to their ecological interactions.

In conclusion, integrating genetic data with species distribution models allows us to understand how the climatic history of the BCP has influenced the distribution of genetic diversity and demographic changes in this species. Since the moths’ life cycle depends on Yucca flowering, which in turn responds to precipitation, climate change is likely to affect the population dynamics of these insects. Periods of extreme drought, such as those occurring in recent decades in the peninsula, may impact moth demography and exacerbate a population decline. Future studies focusing on the ecology and evolution of Prodoxus species associated with Yucca and Hesperoyucca in this region could enhance our understanding of the hidden diversity within this group and complement existing information on the northern species (Smith & Leebens-Mack, 2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Lita Castañeda and Mario Salazar for their help with laboratory analysis, technical support, and assistance in the fieldwork. They also thank Alberto López Alemán for his valuable assistance in improving the English language of the manuscript. This study was supported financially by Secretaría de Ciencia, Humanidades, Tecnología e Innovación (Secihti) (CB-2014-01-238843, infra-2014-1-226339). The Rufford Foundation also provided financial support for a part of this study (RSG 13704-1) and the Jiji Foundation. The authors thank the Associate Editor and the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

Álamo-Herrera, C. R., Arteaga, M. C., Bello-Bedoy, R., & Rosas-Pacheco, F. (2022). Pollen dispersal and genetic diversity of Yucca valida (Asparagaceae), a plant involved in an obligate pollination mutualism. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 136, 364–374. https://doi.org/10.1093/biolinnean/blac031

Álamo-Herrera, C. R., Arteaga, M. C., & Bello-Bedoy, R. (2024). Genetic diversity and phenotypic variation in a parasitoid wasp involved in the yucca – yucca moth interaction. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 95, e955461. https://doi.org/10.22201/ib.20078706e.2024.95.5461

Alemán, A., Arteaga, M. C., Gasca-Pineda, J., & Bello-Bedoy, R. (2024). Divergent lineages in a young species: the case of Datilillo (Yucca valida), a broadly distributed plant from the Baja California Peninsula. American Journal of Botany, 111, e16385. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajb2.16385

Althoff, D. M., Segraves, K. A., Leebens-Mack, J., & Pellmyr, O. (2006). Patterns of speciation in the yucca moths: parallel species radiations within the Tegeticula yuccasella species complex. Systematic Biology, 55, 398–410. https://doi.org/10.1080/10635150600697325

Althoff, D. M., Svensson, G. P., & Pellmyr, O. (2007). The influence of interaction type and feeding location on the phylogeographic structure of the yucca moth community associated with Hesperoyucca whipplei. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 43, 398–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2006.10.015

Althoff, D. M., Segraves, K. A., Smith, C. I., Leebens-Mack, J., & Pellmyr, O. (2012). Geographic isolation trumps coevolution as a driver of yucca and yucca moth diversification. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 62, 898–906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2011.11.024

Arteaga, M. C., Bello-Bedoy, R., León-de la Luz, J. L., Delgadillo, J., & Domínguez, R. (2015). Phenotypic variation of flowering and vegetative morphological traits along the distribution for the endemic species Yucca capensis (Agavaceae). Botanical Sciences, 93, 765–770. https://doi.org/10.17129/botsci.214

Arteaga, M. C., Bello-Bedoy, R., & Gasca-Pineda, J. (2020). Hybridization between yuccas from Baja California: Genomic and environmental patterns. Frontiers in Plant Science, 11, 685. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2020.00685

Bandelt, H. J., Forster, P., & Röhl, A. (1999). Median-joining networks for inferring intraspecific phylogenies. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 16, 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026036

Bouckaert, R., Heled, J., Kühnert, D., Vaughan, T., Wu, C. H., Xie, D. et al. (2014). BEAST 2: a software platform for Bayesian evolutionary analysis. Plos Computational Biology, 10, e1003537. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003537

Darriba, D., Taboada, G. L., Doallo, R., & Posada, D. (2012). jModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and high-performance computing. Nature Methods, 9, 772. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.2109

De la Rosa-Conroy, L., Gasca-Pineda, J., Bello-Bedoy, R., Eguiarte, L. E., & Arteaga, M. C. (2020). Genetic patterns and changes in availability of suitable habitat support a colonisation history of a North American perennial plant. Plant Biology, 22, 233–242. https://doi.org/10.1111/plb.13053

Dolby, G. A., Bennett, S. E. K., Lira-Noriega, A., Wilder, B. T., & Munguia-Vega, A. (2015). Assessing the geological and climatic forcing of biodiversity and evolution surrounding the Gulf of California. Journal of the Southwest, 57, 391–455.

Driscoe, A. L., Nice, C. C., Busbee, R. W., Hood, G. R., Egan, S. P., & Ott, J. R. (2019). Host plant associations and geography interact to shape diversification in a specialist insect herbivore. Molecular Ecology, 28, 4197–4211. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.15220

Drummond, A. J., Rambaut, A., Shapiro, B. E. T. H., & Pybus, O. G. (2005). Bayesian coalescent inference of past population dynamics from molecular sequences. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 22, 1185–1192. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msi103

Drummond, C. S., Xue, H. J., Yoder, J. B., & Pellmyr, O. (2010). Host-associated divergence and incipient speciation in the yucca moth Prodoxus coloradensis (Lepidoptera: Prodoxidae) on three species of host plants. Heredity, 105, 183–196. https://doi.org/10.1038/hdy.2009.154

Engelmann, G. (1872). The flower of yucca and its fertilization. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club, 3, 33.

Excoffier, L., Laval, G., & Schneider, S. (2005). Arlequin (version 3.0): an integrated software package for population genetics data analysis. Evolutionary Bioinformatics Online, 2005, 47–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/117693430500100003

Fick, S. E., & Hijmans, R. J. (2017). WorldClim 2: new 1-km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. International Journal of Climatology, 37, 4302–4315. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.5086

Futuyma, D. J. (2000). Some current approaches to the evolution of plant–herbivore interactions. Plant Species Biology, 15, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1442-1984.2000.00029.x

Gloss, A. D., Dittrich, A. C. N., Goldman-Huertas, B., & Whiteman, N. K. (2013). Maintenance of genetic diversity through plant–herbivore interactions. Current Opinion in Plant Biology, 16, 443–450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbi.2013.06.002

Gloss, A. D., Groen, S. C., & Whiteman, N. K. (2016). A genomic perspective on the generation and maintenance of genetic diversity in herbivorous insects. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 47, 165–187. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-121415-032220

Leebens-Mack, J., Pellmyr, O., & Brock, M. (1998). Host specificity and the genetic structure of two yucca moth species in a yucca hybrid zone. Evolution, 52, 1376–1382. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.1998.tb02019.x

Leebens-Mack, J., & Pellmyr, O. (2004). Patterns of genetic structure among populations of an oligophagous pollinating Yucca moth (Tegeticula yuccasella). Journal of Heredity, 95, 127–135. https://doi.org/10.1093/jhered/esh025

Lenz, L. W. (1998). Yucca capensis (Agavaceae, Yuccoideae), a new species from Baja California Sur, Mexico. Cactus and Succulent Journal, 70, 289–296.

Liu, S., Jiang, N., Xue, D., Cheng, R., Qu, Y., Li, X. et al. (2016). Evolutionary history of Apocheima cinerarius (Lepidoptera: Geometridae), a female flightless moth in northern China. Zoologica Scripta, 45, 160–174. https://doi.org/10.1111/zsc.12147

Nakamura, H., Teshima, K., & Tachida, H. (2018). Effects of cyclic changes in population size on neutral genetic diversity. Ecology and evolution, 8, 9362–9371. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.4436

Papadopoulou, A., Anastasiou, I., & Vogler, A. P. (2010). Revisiting the insect mitochondrial molecular clock: the mid-Aegean trench calibration. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 27, 1659–1672. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msq051

Pellmyr, O. (2003). Yuccas, yucca moths, and coevolution: a review. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden, 90, 35–55.

Pellmyr, O., Balcazar-Lara, M., Segraves, K. A., Althoff, D. M., & Littlefield, R. J. (2008). Phylogeny of the pollinating yucca moths, with revision of Mexican species (Tegeticula and Parategeticula; Lepidoptera, Prodoxidae). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 152, 297–314. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.2007.00361.x

Phillips, S. J., Anderson, R. P., & Schapire, R. E. (2006). Maximum entropy modeling of species geographic distributions. Ecological Modelling, 190, 231–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2005.03.026

Rambaut, A., Drummond, A. J., Xie, D., Baele, G., & Suchard, M. A. (2018). Posterior summarization in Bayesian phylogenetics using Tracer 1.7. Systematic Biology, 67, 901–904. https://doi.org/10.1093/sysbio/syy032

Rogers, A. R., & Harpending, H. (1992). Population growth makes waves in the distribution of pairwise genetic differences. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 9, 552–569. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040727

Rozas, J., Sánchez-Del Barrio, J. C., Messeguer, X., & Rozas, R. (2003). DnaSP, DNA polymorphism analyses by the coalescent and other methods. Bioinformatics, 19, 2496–2497. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btg359

Segraves, K. A., & Pellmyr, O. (2001). Phylogeography of the yucca moth Tegeticula maculata: the role of historical biogeography in reconciling high genetic structure with limited speciation. Molecular Ecology, 10, 1247–1253. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-294X.2001.01275.x

Smith, C. I., Godsoe, W. K., Tank, S., Yoder, J. B., & Pellmyr, O. (2008). Distinguishing coevolution from covicariance in an obligate pollination mutualism: asynchronous divergence in Joshua tree and its pollinators. Evolution, 62, 2676–2687. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00500.x

Smith, C. I., Drummond, C. S., Godsoe, W., Yoder, J. B., & Pellmyr, O. (2009). Host specificity and reproductive success of yucca moths (Tegeticula spp. Lepidoptera: Prodoxidae) mirror patterns of gene flow between host plant varieties of the Joshua tree (Yucca brevifolia: Agavaceae). Molecular Ecology, 18, 5218–5229. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04428.x

Smith, C. I., Tank, S., Godsoe, W., Levenick, J., Strand, E., Esque, T. et al. (2011). Comparative phylogeography of a coevolved community: concerted population expansions in Joshua trees and four yucca moths. Plos One, 6, e25628. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0025628

Smith, C. I., & Leebens-Mack, J. H. (2024). 150 Years of coevolution research: evolution and ecology of yucca moths (Prodoxidae) and their hosts. Annual Review of Entomology, 69, 375–391. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-022723-104346

Tamura, K., Dudley, J., Nei, M., & Kumar, S. (2007). MEGA4: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 24, 1596–1599. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msm092

Turner, R. M., Bowers, J. E., & Burgess, T. L. (1995). Sonoran Desert plants: an ecological atlas. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.