Joselin Judith Peña-Herrera a, Yury Glebskiy a, b, *, Teresa de Jesús Hernández-Trejo a, Zenón Cano-Santana a

a Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Facultad de Ciencias, Departamento de Ecología y Recursos Naturales, Laboratorio de Interacciones y Procesos Ecológicos, Circuito Exterior s/n, Ciudad Universitaria, Coyoacán, 04510 Ciudad de México, Mexico

b Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Facultad de Ciencias, Posgrado en Ciencias Biológicas, Circuito Exterior s/n, Ciudad Universitaria, Coyoacán, 04510 Ciudad de México, Mexico

*Corresponding author: agloti@ciencias.unam.mx (Y. Glebskiy)

Received: 14 September 2023; accepted: 6 March 2024

Abstract

Seed dispersal by animals is a key ecosystemic process in many environments; however, it could be compromised or increased in urban environments due to changes in the landscape, the introduction of exotic species, and human activities. This article aims to evaluate the role of ringtails (Bassariscus astutus) as seed dispersers in an urban-natural gradient during low human activity due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Ringtail feces were collected in 3 sampling sites with different levels of urbanization (ranging from 100 to 5% of natural vegetation), and the seeds germinated in germination chambers. Twenty species of plants were dispersed by ringtails, more than reported in previous studies. More seeds were dispersed in natural (7.1 seeds per g) than urbanized (3.2 seeds per g) areas, but diversity and richness were higher in urbanized areas. This suggests that urban environments have a greater diversity, and it could be attributed to the microenvironments created by urban infrastructure and the exotic plants that are established in the area.

Keywords: Endozoochory; Mexico City; Opuntia; REPSA; Zoochory

© 2024 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Biología. Este es un artículo Open Access bajo la licencia CC BY-NC-ND

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Cacomixtles (Bassariscus astutus) como dispersores de semillas en un gradiente urbano bajo condiciones de baja actividad humana por COVID-19

Resumen

La dispersión de semillas por animales es un proceso clave en muchos ecosistemas, pero este se puede ver comprometido o incrementado en ambientes urbanos debido a cambios en el paisaje, introducción de especies exóticas y actividades humanas. El objetivo de este artículo es evaluar el papel del cacomixtle (Bassariscus astutus) como dispersor de semillas en un gradiente urbano-natural durante un periodo de baja actividad humana debido a la pandemia de COVID-19. Se colectaron excretas de cacomixtles en 3 localidades con diferente grado de urbanización (entre 100 y 5% de vegetación natural) y las semillas fueron germinadas en cámaras de germinación. Se registraron 20 especies de plantas dispersadas, más que lo reportado en estudios previos. Más semillas fueron dispersadas en áreas naturales (7.1 semillas por g) que urbanizadas (3.2 semillas por g), pero la riqueza y diversidad fueron mayores en áreas urbanizadas. Ésto sugiere que la diversidad en ambientes urbanos es mayor, lo cual se puede atribuir a los microambientes formados por la infraestructura urbana y las plantas exóticas establecidas en el área.

Palabras clave: Endozoocoria; Ciudad de México; Opuntia; REPSA; Zoocoria

Introduction

Some animals may provide a key ecosystemic service, acting as seed dispersers, which allow many plant species to effectively move their offspring and maintain plant communities across different environments. An example of those animals is the ringtail (Procyonidae: Bassariscus astutus) which is an omnivorous and opportunistic animal that has shown potential to disperse the seeds of a great number of plant species across many ecosystems (Alexander et al., 1994; Rodríguez-Estrella et al., 2000; Rubalcava-Castillo et al., 2020). However, this important service could be diminished in urban ecosystems, where ringtails are very common (Barja & List, 2006; Swanson et al., 2022). Because urban areas offer new sources of food like anthropogenic waste and a variety of exotic plants, ringtails could disperse fewer seeds or seeds of exotic plants. This is an important concern since urban ecosystems are growing fast and thus becoming important areas for the conservation of species and areas on which we rely to obtain ecosystemic services.

Previous studies suggest that seed dispersal is diminished in cities due to a great number of unsuitable habitats (Cheptou et al., 2008) and barriers that obstruct animal movement and thus seed dispersal (Niu et al., 2018). However, animal-plant networks are persistent in cities (Cruz et al., 2013), and plants that rely on animal dispersal tend to have a more successful regeneration of populations than plants that rely on other strategies for dispersal (Niu et al., 2023). At the same time, most studies show that urban ecosystems tend to be more diverse than natural areas due to the great number of exotic species, microenvironments that can host greater plant diversity, and the fact that cities tend to be built in highly diverse locations (Kühn et al., 2004; Wania et al., 2006). Yet all these studies are performed in urban areas with both human activity and urban infrastructure; therefore, the hypothesis that urban areas are diverse due to the exotic plants and microhabitats and not due to “direct-human” seed dispersal (for example, seeds we throw away as garbage) is yet to be proven.

Particularly for the ringtails, Cisneros-Moreno and Martínez-Coronel (2019) found differences in the urban and rural ringtail diets. They report that in urban environments, ringtails consume 11 plant species, and 9 in rural environments. Other studies also show that ringtails commonly consume human-generated waste from trash cans when it is available (Castellanos et al., 2009; Picazo & García-Collazo, 2019). However, all those studies were made under normal human activity, but if it is reduced, the generation of waste could be diminished, affecting the ringtail diet, which in turn could lead to a change in their role as seed dispersers.

Therefore, this article aims to compare the diversity, abundance, and species of seeds dispersed by ringtails in 3 areas with different levels of urbanization during a time of reduced human activity due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Materials and methods

This study was performed inside the main campus of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Mexico, located in Mexico City, Mexico. The campus contains a well-preserved ecological reserve (Reserva Ecológica del Pedregal de San Ángel; henceforth REPSA) and urban areas such as buildings and roads, all of which are surrounded by the Mexico City (Fig. 1). Therefore, a gradient between urban and natural areas can be found in a relatively small area (730 ha; Zambrano et al., 2016) that otherwise shares all environmental characteristics like mean temperature (18.2°C), precipitation (752 mm), original substrate, and vegetation: xerophitic shrubs (Rzedowski, 1954; SMN, 2023).

An important characteristic of this study is that it was performed under lockdown conditions due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Because of the rapid spreading of the virus, most activities on campus were switched to virtual mode; students took lessons from home; maintenance such as cleaning, gardening, and security were kept to a bare minimum; and all research activities had to be done from home, except for some specific cases, such as this study, that required special permission from the university. Those measures were implemented in March 2020 and began to be gradually lifted in the spring of 2022. Under normal conditions, the campus is visited by 166,474 people, and 70,000 vehicles, and 15 tons of waste (excluding gardening products) are generated (Zambrano et al., 2016). However, as a result of the pandemic, human activity on campus such as driving, waste generation and gardening, among others was minimal for 2 years. This gave us the opportunity to study the ringtail seed dispersal in an urban environment without human presence.

The correct identification of ringtail feces is an essential part of this project, since, in our study site, they could be confused with excretes of opossums (Didelphis virginiana). Previous studies suggest that opossums do not use latrines (Aranda, 2000), however, to ensure that latrines are used exclusively by ringtails, we placed camera traps in front of 8 latrines, and animal interactions with those latrines were recorded.

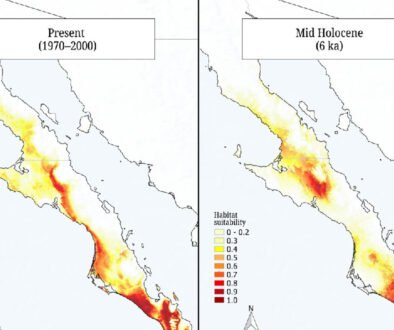

Figure 1. Map of the study location. Blue dots, Faculty (most urbanized area) latrines; red dots, the Institute latrines (semi-urban area); and green dots, the West core (natural area). The lines represent the 178 m around the latrines in which the percentages of the different types of terrain were calculated.

Three areas separated by at least 800 m were chosen to represent the urban-natural gradient: natural, semi-urban, and urban (Fig. 1). The home ranges of this species in the location are small: between 3 and 9.9 ha (Castellanos & List, 2005); therefore, this separation should ensure independence between the treatments. The level of urbanization was based on the percentage of area covered by natural vegetation, altered vegetation, impermeable areas without buildings (mainly roads and parking lots), and buildings found in a 178 m area (Fig. 1, Table 1) around the sampling points (178 m is the radius of the maximum activity area reported for ringtails in this particular location; Castellanos & List, 2005). The natural area (henceforth the West core) is located inside the west core of the REPSA. Vegetation consists mainly of shrubs, and Opuntia cactus is quite common (Cano-Santana, 1994). The semi-urban area (henceforth Institutes) is located around the humanitarian institutes area and consists of a mosaic of spatially located buildings, parking lots, altered vegetation (grass and some cultivated trees, mostly without fruit) and remnants of natural vegetation that surround this area on all sides (Fig. 1, Flores-Morales, 2023). The urban area (henceforth Faculty) is located inside the faculty of sciences and is dominated by tightly packed buildings divided by impermeable areas and gardens. The vegetation is diverse and includes a small amount of native plants such as Opuntia, but mostly consists of grass and introduced trees some of which have fruits that could be consumed by ringtails (Mendoza-Hernández & Cano-Santana, 2009). During the lockdown, gardens were left mostly unattended, and some alimentary plants began to grow (for example, we encountered several tomato plants with ripe fruits). The natural vegetation is located mostly on the edges of this area (Fig. 1).

Table 1

Amount of terrain coverage in the sampling areas. Impermeable areas were considered all areas covered with concrete but without buildings, mainly roads and parking lots.

| Natural vegetation (%) | Altered vegetation (%) | Buildings (%) | Impermeable areas (%) | Total area (ha) | |

| West core | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 34.1 ha |

| Institutes | 49.2 | 24.2 | 7 | 19.6 | 30.7 ha |

| Faculty | 4.9 | 35 | 30.5 | 29.6 | 15.4 ha |

To estimate the number of seeds dispersed by ringtails, we collected excretes from 13 latrines in each location, on January 18th 2022. Since previous studies report that seeds in our study area commonly have dormancy (Glebskiy, 2019), half of each latrine excretes was placed in plastic bags and half in mesh bags (with 1 × 1 mm openings). Both treatments were left in the field (on the soil and without cover) until April 29th 2022 (when the rains and thus the germination period started). The advantage of the plastic bag treatment is that it allows the seeds to experience the temperature changes that are responsible for ending dormancy in most plants and protects the seeds, but limits some other factors like gas exchange and humidity that could potentially contribute to the end of dormancy (Baskin & Baskin, 1998). On the other hand, the mesh bag allows for a better representation of the natural conditions to which seeds are exposed but is susceptible to losing seeds through the mesh and the addition of new seeds from the environment. Both methods were tested.

At the beginning of the rainy season (April 29th 2022) bags were collected and put to germinate in commercial soil (the soil was sterilized by microwaving, and a control with no excretes was used to test the efficiency of sterilization and possible future seed additions) in a germination chamber (25°C, 16 hours of light, and 8 hours of darkness) for 4 months. All plant germinations were recorded and identified to morphospecies; when the plants grew, they were identified to the finest level possible. Species that germinated in the control pot were considered later additions and excluded from the analysis.

Data were analyzed with the R statistical packages: stats (R core team, 2022), dunn.test (Dinno, 2017), fossil (Vavrec, 2011), and vegan (Oksanen et al., 2022). Number of germinated seeds per gram of excrete was calculated. To compare between treatments (3 locations and 2 types of protection bags) Kruskal-Wallis and Dunn tests were performed for the total number of germinated seeds and the number of Opuntia seeds (this was the only species with enough data to analyze independently). A GLIM test (with Poisson distribution) was used to determine if the level of protection (plastic bags = 1, mesh bags = 0) and amount of vegetation (both natural and altered) influenced the amount of total and Opuntia germinated seeds. To compare the richness and diversity of dispersed seeds, we calculated the Shannon diversity and Chao 1 (± 95% confidence interval) richness. The similarity between treatments was measured using the Jaccard and Bray-Curtis indexes.

Results

A total effort of 329 trap nights was performed with 199 independent records (at least 1 hour between sightings) of ringtails, of which 44 times ringtails defecated in the latrine (Fig. 2). Opossums were observed 66 times, and no defecation was observed. At the same time, there were 9 observations of rodents and 7 of birds feeding from the latrines.

A total of 52 bags were recovered from the field (34 plastic, and 18 mesh bags), and were put to germinate. In total, 782 plants of 20 species (Table 2) germinated in this experiment. More seeds per gram of excrete germinated in the mesh bags treatment (U tests; V = 1,225, p < 0.001); however, more Opuntia seeds germinated in the plastic bag treatment (U test; V = 300, p < 0.001; Table 3). The Kruskal-Wallis test showed no differences in the number of germinated seeds between locations in the mesh bags, but there were significant differences for total seed and Opuntia seeds in the plastic bag treatment (p = 0.042 and p = 0.002). According to the Dunn test, there were fewer total seeds in the Faculty area than the West core (p = 0.009) and fewer Opuntia seeds in the Faculty area than the Institutes (p = 0.015) and the West core (p = 0.009).

GLIM analysis showed that both level of protection (-0.818, p < 0.001) and vegetation area (1.279, p < 0.001) are significant predictors for the number of total seeds germinated. For Opuntia seeds, protection (1.674, p < 0.001) and vegetation (3.559, p < 0.001).

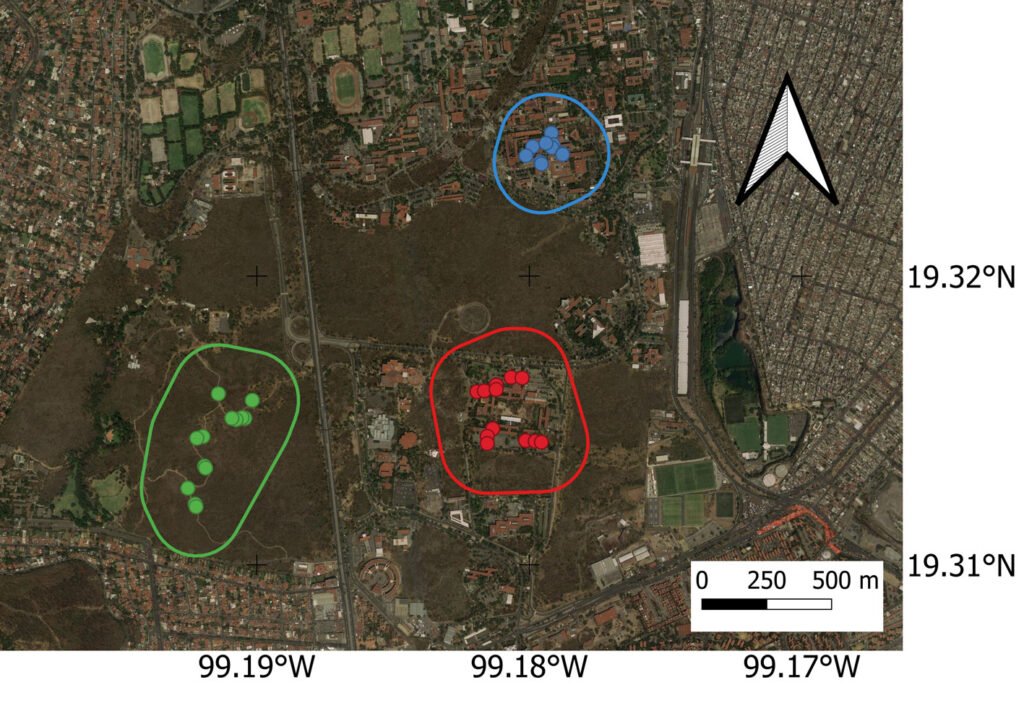

Figure 2. a) Ringtail defecating in a latrine; b) a rodent consuming seeds from a latrine; c) a latrine; d) plants germinated from excretes.

We found significant differences in richness (according to Chao1) between the Faculty area and the West core (in plastic bags) and between the Faculty area and Institutes and the West core (in mesh bags; Table 4). The Bray-Curtis dendrogram shows 2 important groups: the mesh bag treatment and the plastic bag (Fig. 3). Jaccard index showed the following results within the same location,Faculty plastic-Faculty mesh: 0.714, Institutes plastic-Institutes mesh: 0.546, West core plastic-West core mesh: 0.571, total plastic-total mesh: 0.65; between locations,plastic bags, Faculty plastic-Institutes plastic: 0.769, Faculty plastic-West core plastic: 0.5, Institutes plastic-West core plastic: 0.643;between locations, mesh bags, Faculty mesh-Institutes mesh: 0.5, Faculty mesh-West core mesh: 0.294, Institutes mesh-West core mesh: 0.333.

Figure 3. Bray-Curtis dendrogram of germination treatments. First letter represents the location, W: west core, I: Institutes, F: Faculty; second letter, the type of bag: M: mesh, P: plastic.

Discussion

The camera trap experiment was designed to prove that the latrines from which we collected excretes belong to ringtails and not opossums since those animals produce very similar feces (Aranda, 2000). Given that we observed 44 events of defecation by ringtails and zero by opossums, it we can conclude that ringtails are the only latrine users. However, at the same time, rodents and birds were seen feeding in those latrines (Fig. 2). The ratio for those visits is 1 visit per 2.8 defecations, and this is important for seed dispersal, since most likely those visitors feed on seeds that are dropped by ringtails and can selectively remove some species. At the same time, it is interesting to consider the trade-off for the rodents that consume seeds from ringtail latrines since they are exposed to predation by the latrine owners. Although it is outside the scope of this research, we consider that the interaction around the latrines is a topic that should be further investigated to better understand the role of these animals as seed dispersers and the interactions that the latrines produce.

The comparison between plastic and mesh bags shows differences between the treatments, especially in the number of seeds that germinated per gram of excrete (Tables 2, 3). This could be attributed to the fact that mesh bags allow the smallest particles to exit the bag, and the total weight of feces diminishes while the number of seeds remains constant. Therefore, the mesh bag treatment is not adequate for estimating the number of seeds per gram of excrete, although data concerning the diversity and richness of seeds is still valid. Given the above and the fact that there were more plastic bag replicas, the data interpretation in this research is based on the plastic bag treatment.

Table 2

Number of seeds per gram of excrete in all treatments for each plant species.

| Species | Common name | Faculty | Institutes | West core | |||

| Plastic | Mesh | Plastic | Mesh | Plastic | Mesh | ||

| Ageratina sp. 1 | Snakeroot | 0.11 | 3.19 | 0.41 | 2.95 | 0.12 | 8.63 |

| Ageratina sp. 2 | Snakeroot | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Asclepias linaria | Pineneedle milkweed | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.13 | 0 |

| Amaranthaceae | 0.33 | 0.19 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Bidens sp. | Beggarticks | 0 | 0 | 0.02 | 0 | 0.05 | 0.61 |

| Cissus sicyoides | Princess vine | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.03 | 0.33 |

| Conyza sp. | Horseweed | 0.07 | 0.22 | 0.26 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Drymaria laxiflora | Chickweed | 0.04 | 0.27 | 0.12 | 0.35 | 0.03 | 2.68 |

| Eragrostis sp. | Lovegrass | 0 | 0.09 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Iresine sp. | Bloodleaf | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.04 |

| Opuntia sp. | Prickly pear | 0.23 | 0.98 | 2.23 | 0.59 | 6.36 | 0.24 |

| Solanaceae | 0.03 | 0.27 | 0.08 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.71 | |

| Solanum nigrescens | Slender nightshade | 0.1 | 2.79 | 0.04 | 2.14 | 0.08 | 0 |

| Stevia sp. | Stevia | 0 | 0.09 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Phytolacca icosandra | Tropical pokeweed | 0.46 | 0.15 | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.08 | 0 |

| Poaceae 1 | 0.02 | 0.39 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.17 | |

| Poaceae 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.25 | |

| Unknown sp. 1 | 0.02 | 0 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.05 | 0.33 | |

| Unknown sp. 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.05 | 0 | |

| Unknown sp. 3 | 1.72 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Table 3.

Number of Opuntia and total seeds dispersed by ringtails in different environments. Values given in seeds per g of excrete ± S.D.

| Total seeds | Opuntia seeds | |||

| Plastic | Mesh | Plastic | Mesh | |

| West core | 7.13 ± 8.06 | 15.99 ± 13.85 | 6.36 ± 7.58 | 0.24 ± 0.3 |

| Institutes | 3.64 ± 2.87 | 6.33 ± 6.61 | 2.23 ± 2.72 | 0.59 ± 1.33 |

| Faculty | 3.16 ± 7.09 | 8.72 ± 5.51 | 0.23 ± 0.75 | 0.98 ± 2.39 |

| Total | 4.7 ± 6.64 | 10.88 ± 10.26 | 2.96 ± 5.46 | 0.58 ± 1.5 |

GLIM analysis shows a positive relation between the number of seeds dispersed by ringtails and vegetation cover. Therefore, ringtails disperse fewer seeds in urban areas (Table 3); however, diversity and richness tend to be higher in the Faculty, the most urbanized location (Table 4).

Table 4

Richness (Chao1 ± 95% confidence intervals) and diversity (Shannon) of seeds dispersed by ringtails.

| Faculty | Institutes | West core | Total | |||||||||

| Plastic | Mesh | Total | Plastic | Mesh | Total | Plastic | Mesh | Total | Plastic | Mesh | Total | |

| Observed richness | 12 | 12 | 14 | 11 | 6 | 11 | 12 | 10 | 14 | 16 | 17 | 20 |

| Chao1 | 16 ± 2.65 | 14.67 ± 1.85 | 18.5 ± 3.9 | 15 ± 2.65 | 8 ± 1.87 | 17 ± 0 | 12.17 ± 0.34 | 10.25 ± 0.44 | 14.5 ± 0.73 | 16.25 ± 0.44 | 19.67 ± 1.85 | 24.5 ± 3.4 |

| Shannon | 1.45 | 1.839 | 1.889 | 1.273 | 1.434 | 1.466 | 0.564 | 1.758 | 1.122 | 1.403 | 2.041 | 1.779 |

This is consistent with most previous studies that show a greater diversity of seeds in urban settings (Kühn et al., 2004; Wania et al., 2005), and that ringtails consume more plant species in the cities (Cisneros-Moreno & Martínez-Coronel, 2019). At our location, ringtails disperse fewer seeds in urban areas, but their richness and diversity are higher. The novel contribution of this research is that it was performed in an urban area with very little human activity; therefore, the direct effect of human activities such as waste generation and gardening could not explain the differences between treatments. At the same time, all 3 locations share very similar climatic conditions and originally were the same ecosystem. This suggests that differences between treatments are not due to original conditions (although it has been proven in other locations; Kühn et al., 2004). The high diversity of seeds in urbanized areas can be attributed to the great variety of habitats found in an urban area and the exotic species that have already been established there.

Ringtails are common in urban areas, and Castellanos et al. (2009) suggest they prefer disturbed areas over natural ones. This could be due to food availability in urbanized areas, and previous studies show that ringtails have a greater variety of food in urban areas. For example, Cisneros-Moreno and Martínez-Coronel (2019) show that an urban population consumes 36 food items and a rural population registered 28 items. Another advantage that cities offer is infrastructure. Poglayen-Neuwall and Toweill (1988) mention that rocky habitats favor ringtails, and human-made buildings provide a similar habitat. Interestingly, some data suggests that in the absence of humans, sightings of those animals in urban areas increased (Tzintzun-Sánchez, 2022; pers. obs.). This suggests that the benefits ringtails obtain from cities don’t come directly from human activities since, even without our presence, those animals have the benefits of infrastructure and a more diverse diet. However, further studies are needed to fully prove this hypothesis.

Previous studies have reported that fruits are important in the diet of B. astutus; however, the number of different plant species is generally low (13, ~ 9, 10, Alexander et al. [1994], Harrison [2012], and Rodríguez-Estrella et al. [2000], accordingly). In this study, 20 species of seeds were found and it is noteworthy that the cited articles included all vegetal matter in their analysis while this study only considers seeds that germinated. This suggests that the diversity of plants that are consumed in our site is much higher than usual. This could be the result of higher plant diversity in the location, or that ringtails tend to have a more frugivore diet here, this last hypothesis is supported by personal observations of the authors.

Based on the above, it could be concluded that there are several animals that consume the latrine contents, and this interaction could be important for seed dispersal. Ringtails disperse more seeds in natural areas, but their richness is higher in urban areas even in the absence of human activity.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to M. E. Muñiz-Díaz for facilitating the germination chambers and her advice during this research, to Y. Martínez-Orea for helping with plant identification, to I. Castellanos-Vargas for technical support, and to the SEREPSA working team for facilitating the permission to perform this research. This project was financially supported by PAPIIT grant IN212121 (“El efecto de la urbanización sobre el tlacuache Didelphis virginiana en un matorral xerófilo de la Ciudad de México”), awarded to ZCS.

References

Alexander, L. F., Verts, B. J., & Farrell, T. P. (1994). Diet of ringtails (Bassariscus astutus) in Oregon. Northwestern Naturalist, 75, 97–101. https://doi.org/10.2307/353683131

Aranda, M. (2000). Huellas y otros rastros de los mamíferos grandes y medianos de México. Cuernavaca, Morelos: Instituto de Ecología, A.C./ la Comisión Nacional para el conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad.

Barja, I., & List, R. (2006). Faecal marking behaviour in ringtails (Bassariscus astutus) during the non-breeding period: spatial characteristics of latrines and single faeces. Chemoecology, 16, 219–222. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00049-

006-0352-x

Baskin, C. C., & Baskin, J. M. (1998). Seeds: ecology, biogeography, and, evolution of dormancy and germination. San Diego: Academic Press.

Cano-Santana, Z. (1994). Flujo de energía a través de Sphenarium purpuracens (Orthoptera: Acrididae) y productividad primaria neta aérea en una comunidad xerófila (Ph.D. Thesis). Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. México D.F.

Castellanos, G., García, N., & List, R. (2009). Ecología del cacomixtle (Bassariscus astutus) y la zorra gris (Urocyon cinereoargenteus). In A. Lot, & Z. Cano (Eds.), Biodiversidad del ecosistema del Pedregal de San Ángel (pp. 371–381). Ciudad de Mexico: Secretaria Ejecutiva de la REPSA-UNAM.

Castellanos, G., & List, R. (2005). Área de actividad y uso de hábitat del cacomixtle (Bassariscus astutus) en “El Pedregal de San Ángel”. Revista Mexicana de Mastozoología, 9, 113–122.

Cheptou, P. O., Carrue, O., Rouifed, S., & Cantarel, A. (2008). Rapid evolution of seed dispersal in an urban environment in the weed Crepis sancta. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105, 3796–3799. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0708446105

Cisneros-Moreno, C., & Martínez-Coronel, M. (2019). Alimentación del cacomixtle (Bassariscus astutus) en un ambiente urbano y uno agrícola en los valles centrales de Oaxaca. Revista Mexicana de Mastozoología (Nueva Época), 9, 31–43. https://doi.org/10.22201/ie.20074484e.2019.1.1.274

Cruz, J. C., Ramos, J. A., Da Silva, L. P., Tenreiro, P. Q., & Heleno, R. H. (2013). Seed dispersal networks in an urban novel ecosystem. European journal of forest research, 132, 887–897. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10342-013-0722-1

Dinno, A. (2017). dunn.test: Dunn’s Test of Multiple Comparisons Using Rank Sums. R package version 1.3.5, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=dunn.test

Flores-Morales, I. (2023). Diversidad vegetal y animal de los pedregales remanentes de la Zona de Institutos de Investigaciones en Humanidades de Ciudad Universitaria, Ciudad de México, México (Bachelor’s Thesis). Facultad de Ciencias, UNAM. Mexico City.

Glebskiy, Y. (2019). Efecto del conejo castellano (Sylvilagus floridanus) sobre la comunidad vegetal del Pedregal de San Ángel. (M. Sc. Thesis). Facultad de Ciencias, UNAM. México City.

Harrison, R. L. (2012). Ringtail (Bassariscus astutus) ecology and behavior in central New Mexico, USA. Western North American Naturalist, 72, 495–506. https://doi.org/

10.3398/064.072.0407

Kühn, I., Brandl, R., & Klotz, S. (2004). The flora of German cities is naturally species rich. Evolutionary Ecology Research, 6, 749–764.

Mendoza-Hernández, P. E., & Cano-Santana, Z. (2009). Elementos para la restauración ecológica de pedregales: la rehabilitación de áreas verdes de la Facultad de Ciencias en Ciudad Universitaria. In A. Lot, & Z. Cano-Santana (Eds.), Biodiversidad del ecosistema del Pedregal de San Ángel (pp. 523–532). Ciudad de México: Secretaría Ejecutiva de la REPSA-UNAM.

Niu, H., Rehling, F., Chen, Z., Yue, X., Zhao, H., Wang, X. et al. (2023). Regeneration of urban forests as influenced by fragmentation, seed dispersal mode and the legacy effect of reforestation interventions. Landscape and Urban Planning, 233, 104712. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2023.104712

Niu, H. Y., Xing, J. J., Zhang, H. M., Wang, D., & Wang, X. R. (2018). Roads limit of seed dispersal and seedling recruitment of Quercus chenii in an urban hillside forest. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 30, 307–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2018.01.023

Oksanen, J., Simpson, G., Blanchet, F., Kindt, R., Legendre, P., Minchin, P. et al. (2022). vegan: Community Ecology Package. R package version 2.6-2, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan

Picazo, G. E. R. C., & García-Collazo, R. (2019). Comparación de la dieta del cacomixtle norteño, Bassariscus astutus de un bosque templado y un matorral xerófilo, del centro de México. Biocyt: Biología, Ciencia y Tecnología, 12, 834–845. https://doi.org/10.22201/fesi.20072082.2019.12.68527

Poglayen-Neuwall, I., & Toweill, D. E. (1988). Bassariscus astutus. Mammalian Species, 327, 1–8.

R Core Team (2022). R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/

Rodríguez-Estrella, R., Moreno, A. R., & Tam, K. G. (2000). Spring diet of the endemic ring-tailed cat (Bassariscus astutus insulicola) population on an island in the Gulf of California, Mexico. Journal of Arid Environments, 44, 241–246. https://doi.org/10.1006/jare.1999.0579

Rubalcava-Castillo, F. A., Sosa-Ramírez, J., Luna-Ruíz, J. J., Valdivia-Flores, A. G., Díaz-Núñez, V., & Íñiguez-Dávalos, L. I. (2020). Endozoochorous dispersal of forest seeds by carnivorous mammals in Sierra Fría, Aguascalientes, Mexico. Ecology and Evolution, 10, 2991-3003. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.6113

Rzedowski, J. (1954). Vegetation of Pedregal de San Ángel. Anales de la Escuela Nacional de Ciencias Biológicas, IPN, Mexico, 8, 59 Endozoochorous 129.

SMN (Servicio Meteorológico Nacional). (2023). Normales climatológicas de la estación 00009071 Colonia Educacion (1991-2020). Consulted on 12 September 2023. https://smn.conagua.gob.mx/tools/RESOURCES/Normales_Climatologicas/Normales9120/df/nor9120_09071.TXT

Swanson, A. C., Conn, A., Swanson, J. J., & Brooks, D. M. (2022). Record of an Urban Ringtail (Bassariscus astutus) Outside of its Typical Geographic Range. Urban Naturalist Notes, 9, 1–6.

Tzintzun-Sánchez, C. L. (2022). Efectos de la urbanización en la distribución geográfica y hábitos alimenticios del cacomixtle norteño (Bassariscus astutus) en la Ciudad de México, México (Bachelor’s Thesis). Facultad de Ciencias, UNAM. Ciudad de México.

Vavrek, M. J. (2011). fossil: palaeoecological and palae-

ogeographical analysis tools. Palaeontologia Electronica, 14:1T. http://palaeo-electronica.org/2011_1/238/index.html

Wania, A., Kühn, I., & Klotz, S. (2006). Plant richness patterns in agricultural and urban landscapes in Central Germany —spatial gradients of species richness. Landscape and Urban planning, 75, 97–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.

2004.12.006

Zambrano, L., Rodríguez-Palcios, S., Pérez-Escobedo, M., Gil-Alarcón, G. Camarena, P., & Lot, A. (2016). Reserva Ecológica del Pedregal de San Ángel: atlas de riesgos. Ciudad de Mexico: Secretaría Ejecutiva de la REPSA-UNAM.