Jeremy S. Tiemann a, *, Kevin S. Cummings a, Everardo Barba-Macías b, Charles R. Randklev c

a University of Illinois, Prairie Research Institute, Illinois Natural History Survey, 1816 South Oak Street, Champaign, IL 61820 USA

b El Colegio de la Frontera Sur, Departamento de Ciencias de la Sustentabilidad, Km 15.5 Carretera Reforma s/n, Ranchería Guineo Segunda Seccion, 86280 Villahermosa, Tabasco, Mexico

c Texas A&M University, Natural Resources Institute, A&M AgriLife Research and Extension Center at Dallas, 17360 Coit Road, Dallas, Texas 75252 USA

*Corresponding author: jtiemann@illinois.edu (J.S. Tiemann)

Recieved: 19 May 2023; accepted: 19 March 2024

Abstract

Corbicula spp. are one of the most prolific aquatic invasive species in the world and can have negative effects on aquatic ecosystems. We performed qualitative field surveys, examined literature accounts and natural history museum holdings, and accessed citizen science data sources to document the distribution of Corbicula in Mexico and shared drainages. Through 26 publications (N = 127 records), 312 museum holdings, and 446 iNaturalist records, we documented 885 records pertaining to Corbicula in Mexico and shared drainages with the USA. The first record of the species in Mexico was in 1969, and it has since been reported from 26 of the 32 Mexican states and most of the major river basins throughout the country. However, we suggest Corbicula are more prevalent in Mexico than we report in this work as it is often under sampled or under reported.

Keywords: Exotic species; Invasive species; Asian clams; Bivalvia; Freshwater systems

© 2024 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Biología. Este es un artículo Open Access bajo la licencia CC BY-NC-ND

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Distribución de almejas canasta no nativas (Corbicula spp.) en México

Resumen

Algunas especies de Corbicula son de las especies invasoras acuáticas más prolíficas del mundo y pueden tener efectos negativos en los ecosistemas acuáticos. En este trabajo, realizamos estudios de campo cualitativos, examinamos literatura y registros en museos de historia natural y, además, revisamos datos de ciencia ciudadana para documentar la distribución de Corbicula en México y cuencas compartidas con EUA. A través de 26 publicaciones (N = 127 registros), 312 registros de museos y 446 registros de iNaturalist, documentamos 885 registros pertenecientes a Corbicula en México. El primer registro en México de la especie en el país data de 1969 y, desde entonces, ha sido reportada en 26 de los 32 estados mexicanos y en la mayoría de las principales cuencas hidrográficas del país. Sin embargo, creemos que Corbicula es más prevalente en Mexico de lo que reportamos en este trabajo, ya que frecuentemente no se muestrea o no se reporta de manera suficiente.

Palabras clave: Especies exóticas; Especies invasoras; Almejas asiáticas; Bivalvia; Ambientes dulceacuícolas

Introduction

Basket clams (Cyrenidae: Corbicula spp.), also commonly known as Asian clams, are moderately sized (to 50 mm) freshwater bivalves that have become one of the most successful aquatic invasive species to spread across the globe (Pigneur, Etoundi et al., 2014; Pigneur, Falisse et al., 2014). Native to the temperate/tropical regions of Asia, Africa, and Australia, Corbicula can be found on every continent except Antarctica (Bieler & Mikkelsen, 2019; Morton, 1986; Sousa et al., 2008). Species of the Genus Corbicula have been described as hyper-invasive aliens with great biofouling capabilities (Isom, 1986). Once established, Corbicula species can rapidly become extremely abundant and often affect water supply systems, alter nutrient regimes and food web dynamics, and potentially have deleterious effects to native freshwater mussel populations (Cohen et al., 1984; Counts, 1986; Haag, 2019; Isom, 1986; Sousa et al., 2008).

Corbicula taxonomy is in flux, as is the number of species that have become established outside of its native range (Hoagland, 1986). Corbicula were first recorded in North America in British Columbia, Canada, in 1924, and has since spread throughout the continent to areas in which winter water temperatures do not fall below 2 ºC (Benson & Williams, 2021; McMahon, 1999). At least 3 Corbicula taxa have become established in North America (Haponski & Ó Foighil, 2019; Lee et al., 2005; Tiemann et al., 2017). Corbicula have been sporadically collected in Mexico, with the first occurrence reported in 1969 from an irrigation ditch just north of Cerro Prieto, south of Mexicali in Baja California (Fox, 1970). However, Corbicula were present in the Río Grande/ Río Bravo in the USA as early as 1964 (Benson & Williams, 2021). Since then, it has spread throughout Mexico (Counts, 1991; López et al., 2019; Naranjo-García & Castillo-Rodríguez, 2017). It can become the most prevalent mollusk in streams (Czaja et al., 2022; Tiemann et al., 2020), and threatens to alter biologically diverse aquatic ecosystems in Mexico (Czaja et al., 2023).

Once established, Corbicula often becomes the most abundant benthic bivalve in streams. Tiemann et al. (2020) reported densities > 200 individuals/m2 in a small stream in the Río Conchos basin in northern Mexico. Corbicula life history characteristics (e.g., early sexual maturity, high fecundity, and ability to be actively and passively dispersed) favor rapid colonization and persistence in disturbed and unstable habitats (McMahon, 2002; Minchin & Boelens, 2018; Smith et al., 1986; Thompson & Sparks, 1977; Voelz et al., 1998). We herein attempt to summarize the distribution of Corbicula species in Mexico, as was done in the USA by Benson and Williams (2021).

Materials and methods

Data for Corbicula in Mexico and the shared drainages in the USA (i.e., Río Grande and Río Colorado) were compiled from 4 sources. First, we conducted qualitative freshwater mollusk surveys in the Grande, Pánuco, Papaloapan, and Usumacinta basins in the Mexican states of Chihuahua, San Luis Potosí, Veracruz, Tabasco, and Chiapas in 2017-2022 (see Inoue et al., 2020; Kiser et al., 2022; Tiemann et al., 2020). Second, we reviewed literature accounts of Corbicula in Mexico and shared drainages (Barba-Macías & Trinidad-Ocaña, 2017; Benson & Williams, 2021; Contreras-Arquieta & Contreras-Balderas, 1999; Counts, 1991; Counts et al., 2003; Czaja et al., 2022, 2023; Davis, 1980; Dinger et al., 2005; Fox 1970, 1971; Gutiérrez-Galindo et al., 1988; Hillis & Mayden, 1985; López-López et al., 2009, 2019; Naranjo-García & Castillo-Rodríguez, 2017; Naranjo-García & Meza-Meneses, 2000; Naranjo-García & Olivera-Carrasco, 2014; Ramírez et al., 2022; Ramírez-Herrera & Urbano, 2014; Rico-Sánchez et al., 2020; Ruelas-Inzunza et al., 2007, 2009; Tiemann et al., 2020; Torres-Orozco & Revueltas-Valle, 1996; Trinidad-Ocaña et al., 2018). Third, we gathered from the following natural history museums and collections: Colección Nacional de Moluscos, Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Mexico (CNMO); Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Pittsburgh (CM); Delaware Museum of Natural History, Wilmington (DMNH); Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago (FMNH); Florida Museum, University of Florida, Gainesville (UF); Illinois Natural History Survey, Champaign (INHS); Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University (MCZ); National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution (USNM); New Mexico New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, Albuquerque (NMMNH); Ohio State University Museum of Biological Diversity, Columbus (OSUM); Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History (SBMNH); Strecker Museum, Baylor University, Waco, Texas (SMBU); Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas de la Universidad Juárez del Estado de Durango, Colección de Moluscos (UJMC); University of Michigan Museum of Zoology, Ann Arbor (UMMZ); and the University of Texas – El Paso Biodiversity Collections (UTEP) (most museum codes follow Sabaj [2020]). Lastly, we used data from iNaturalist (www.iNaturalist.org; accessed on 1 November 2023), which is a citizen science sourced database.

We verified or re-identified each record to the species level, if possible, from the image(s) provided on-line, by curators, or those posted on iNaturalist. We excluded those records with missing or imprecise locality data, as well as those that could not be identified (e.g., poor quality photographs) from our database. The database is archived in the Illinois Data Bank (https://doi.org/10.13012/B2IDB-9221608_V1) and is available for future studies.

Results

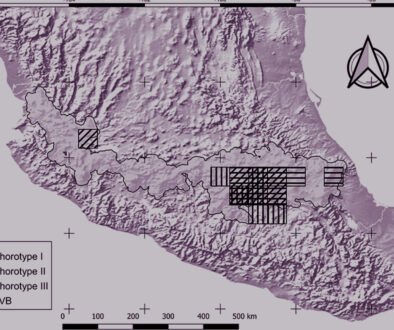

We found 26 publications (N = 127 records), 312 museum lots, and 446 iNaturalist records, which totaled 885 records pertaining to Corbicula in Mexico and shared drainages (684 from Mexico and 201 from the USA; Table 1). Corbicula have been collected throughout Mexico from the Río Grande and Colorado at the U.S. border southward to the Río Usumacinta basin along the Guatemalan border (Fig.1). Corbicula have been collected in a wide variety of waterbodies, including estuarine wetlands, irrigation ditches, manmade impoundments, large rivers, and headwater streams (e.g., < 2 m wide). Corbicula have been recorded from 26 of the 32 Mexican states (Table 1) and most of the major river basins (Table 2), but we feel it is highly probable that Corbicula are more prevalent in Mexico than we report as it is often under-sampled. The 6 Mexican states without verified records include: Aguascalientes, Baja California Sur, Campeche, Mexico City, Tlaxcala, and Yucatán. Citizen scientists provided 4 unique state records for Corbicula in Mexico not reported in the literature or represented in museums (Table 1). In addition, > 50% of the records were from citizen observations via iNaturalist, which demonstrates how citizen scientists can contribute important data, especially in understudied areas.

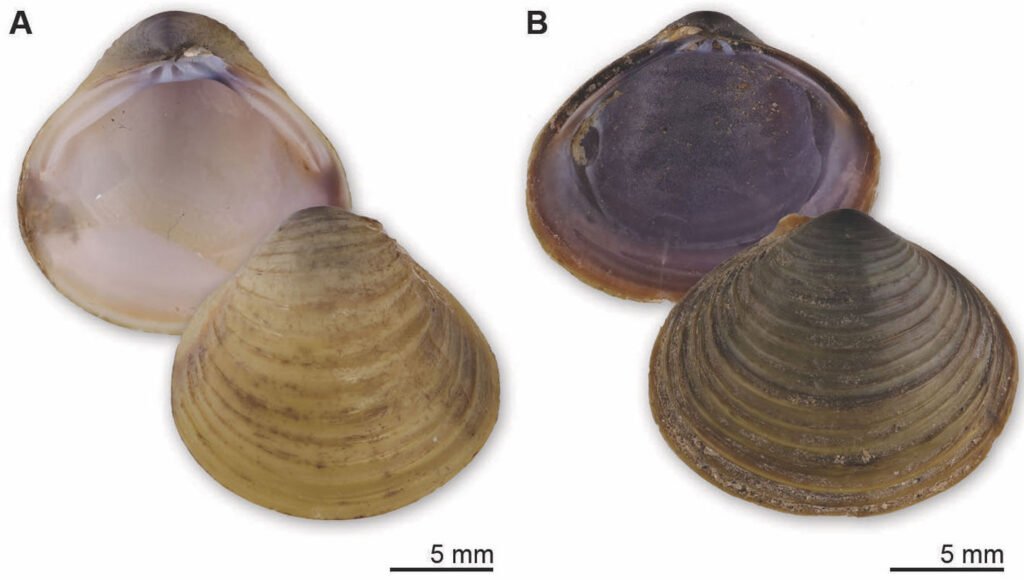

Most Corbicula accounts from Mexico are classified as either Corbicula fluminea (Müller, 1774) or simply Corbicula. However, there are at least 2 Corbicula taxa in Mexico —Corbicula fluminea (form A, white nacre) and Corbicula largillierti (Philippi, 1844) (form B, purple nacre)— as identified by Lee et al. (2005) and Tiemann et al. (2017) (Figs. 1, 2), and both can occur in the same basin, often syntopically (e.g., Río San Juan and Río Soto la Marina basin, Hillis & Mayden, 1985; Río Conchos basin, Tiemann et al., 2020). The distinguishing characteristics are subtle but more pronounced in younger individuals that become less obvious as individuals mature and become large (Tiemann et al., 2017). In young / small (< 25 mm) individuals, C. fluminea has more pronounced external ridges, yellowish periostracum, and white nacre, whereas C. largillierti has less pronounced but tighter ridges, olive periostracum, and purple nacre (Fig. 2). Because most of the specimens examined were from photographs, we could not rule out additional taxa being present in Mexico and we could not verify all records to species, especially those from the historical literature and some iNaturalist photos. We speculate that some unvouchered specimens reported as C. fluminea are likely C. largillierti.

Discussion

Determining the dispersal chronology of Corbicula in Mexico is difficult for a variety of reasons. Unlike freshwater mussels (Unionidae), which are transported within and between river systems via fishes as part of their reproductive cycle, these clams are not dependent on fishes for dispersal. The origins and ensuing dispersion pathways of Corbicula are still poorly known, but it is thought to be a combination of both human-mediated activities such as aquaria releases and bait bucket introductions, and natural dispersal such as passive drift or via intestinal passage through fishes (Gatlin et al., 2013; McMahon, 1999; Naranjo-García & Castillo-Rodríguez, 2017; Sousa et al., 2008). Another confounding factor in determining the chronology of invasion is that there are no regular systematic sampling programs in Mexico that would serve to document the arrival dates in select basins or areas of the country. The literature has also been sporadic and uneven in reporting Corbicula in Mexico. We have summarized the known records and dates of occurrence of Corbicula by major drainage basin (Table 2).

Table 1

List of Mexican states where Corbicula has been found, the year in which the species was first reported, the water body where it was found, the source (citation or museum accession number; museum codes can be found in the methods section) of the first collection, and the number of records we found. These Corbicula records, including data sources, were archived in the Illinois Data Bank (https://doi.org/10.13012/B2IDB-9221608_V1).

| State | First year reported | Waterbody | Source | Number of lots/ records |

| Baja California | 1969 | Irrigation canal, Cerro Prieto | Fox, 1970 | 36 |

| Chiapas | 2009 | Río Lacantún | CNMO 3284, Naranjo-García & Olivera-Carrasco, 2014 | 73 |

| Chihuahua | 1996 | Río Conchos | UTEP 13683, Benson & Williams, 2021 | 107 |

| Coahuila | 1976 | Irrigation canal, Municipio Juarez | UTEP 4836 | 15 |

| Colima | 2006 | Río Armería | CNMO 1720, Naranjo-García & Olivera-Carrasco, 2014 | 6 |

| Durango | 2006 | Presa La Vega, Teuchitlán | CNMO 1679, Naranjo-García & Olivera-Carrasco, 2014 | 53 |

| Estado de México | 2014 | Pond, E of Laguna de Zumpango | iNaturalist, 2023 | 8 |

| Guanajuato | 2018 | Arroyo Hondo | iNaturalist, 2023 | 4 |

| Guerrero | 2009 | Trib. Pacific, W of Petacalco and Río Atoyac | CNMO 5542 | 5 |

| Hidalgo | 2014 | Río Venados | iNaturalist, 2023 | 4 |

| Jalisco | 1981 | Trib. Lago de Chapala | UF 34919, Hillis & Mayden, 1985 | 47 |

| Michoacán | 2008 | Río Atoyac (Balsas) | CNMO 2827, Naranjo-García & Olivera-Carrasco, 2014 | 10 |

| Morelos | 2005 | Río Amacuzac | CNMO 1599 | 9 |

| Nayarit | 1969 | Playa Novillero | DMNH 92579, Hillis & Mayden, 1985 | 7 |

| Nuevo León | 1976 | Ríos Salado and San Juan | UTEP 4860, UTEP 4828 | 33 |

| Oaxaca | 1998 | Dominguillo (S San Juan Bautista Cuicatlán) | CNMO 771, Naranjo-García & Olivera-Carrasco, 2014 | 13 |

| Puebla | 2020 | Río Pantapec | iNaturalist, 2023 | 1 |

| Querétaro | 2017 | Río Jalpan | Rico-Sanchez et al., 2020 | 6 |

| Quintana Roo | 1972 | Unknown | DMNH 237279 | 2 |

| San Luis Potosí | 1993 | Río Huichihuayán | UF 211359, Benson & Williams, 2021 | 29 |

| Sinaloa | 1970 | Río Fuerte | Fox, 1971; Counts, 1991 | 37 |

| Sonora | 1970 | Río Colorado | Counts, 1991 | 28 |

| Tabasco | 2011 | Multiple locations in the Grijalva basin | Barba-Macías & Trinidad-Ocaña, 2017 | 37 |

| Tamaulipas | 1969 | Falcon Reservoir | OSUM 22683 | 41 |

| Veracruz | 1992 | Laguna de Catemaco | Torres-Orozco & Revueltas-Valle, 1996 | 71 |

| Zacatecas | 2006 | Río Juchipila | CNMO 1690, 1692, Naranjo-García & Olivera-Carrasco, 2014 | 2 |

Table 2

List of Mexican rivers/ lakes drainages (Dr.) from north to south where Corbicula spp.have been found and the year first reported. These Corbicula records, including data sources, were archived in the Illinois Data Bank (https://doi.org/10.13012/B2IDB-9221608_V1).

| Waterbody where it was first found | Year of first occurrence |

| Gulf of Mexico Basin | |

| Río Grande Dr. – Falcon Reservoir, Tamaulipas | 1969 |

| Río San Fernando, Tamaulipas | 1974 |

| Río Soto la Marina Dr – unnamed stream, Tamaulipas | 1981 |

| Río Pánuco Dr. – Río Comandante, Tamaulipas | 1990 |

| Río Tecolutla, Veracruz | 2007 |

| Río Papaloapan Dr. – Laguna de Catemaco, Veracruz | 1992 |

| Río Coatzacoalcos, Veracruz | 2005 |

| Río Usumacinta Dr. – Río Lacantún, Chiapas | 2009 |

| Colorado/Gulf of California Basin | |

| Irrigation canal, Baja California | 1969 |

| Río Yaqui, Sonora | 1970 |

| Río Fuerte, Sinaloa | 1970 |

| Pacific Coastal Basin | |

| Río San Pedro, Mezquital, Durango | 2006 |

| Playa Novillero, Nayarit | 1969 |

| Río Grande de Santiago Dr., Jalisco | 1981 |

| Río Ameca, Jalisco | 1982 |

| Río Cuitxmala, Jalisco | 1993 |

| Río Armería, Colima | 1986 |

| Río Atoyac (Balsas), Michoacán | 2008 |

| Río Amacuzac, Morelos | 2005 |

| Caribbean Basin | |

| Cozumel, Quintana Roo | 1971 |

Río Colorado Basin

Corbicula were first reported in the Colorado River at Yuma, Arizona, USA, on the California border in 1955 (Benson & Williams 2021; Counts, 1991). It was first reported from Mexico from an irrigation canal in the Colorado River basin in Baja California in 1969 (Fox 1970). However, there is a specimen (SBMNH 697249) from the Río Cihuatlán (also called the Río Chacala or Marabasco) along the Pacific Coast at Manzanillo, Colima collected in 1965. That locality is problematic, as the Río Cihuatlán does not run through Manzanillo. It does however pass through the city of Cihuatlán, Jalisco. Counts (1991) summarized the occurrences for Corbicula in Mexico and provided a new record for the Río Colorado basin from the Río Mayo (UF 247535), Sonora collected in 1972.

Río Grande del Norte Basin

Corbicula were first found in the Río Grande basin in 1969 in the Falcon Reservoir, Tamaulipas (OSUM 22683) and along the Pacific coast at Playa Novillero in Nayarit (DMNH 92579; Hillis & Mayden, 1985; Counts, 1991; Table 2) —suggesting multiple invasions have occurred, as has been reported elsewhere (Benson & Williams, 2021). Based on collections made as early as 1975 in the upper Río Grande in Texas (Davis, 1980), Benson and Williams (2021) noted that Corbicula were likely present in the states of Chihuahua and Coahuila prior to 1996. This is borne out by museum specimens from the ríos Salado (UTEP 4860) and San Juan (UTEP 4828), Nuevo León collected by A.L. Metcalf in May 1976, an irrigation canal at Municipio Villa Juárez, Coahuila in 1976, and the Río Escondido, Coahuila in 1978 (UTEP 6810). Contreras-Arquieta and Contreras-Balderas (1999) reported Corbicula as common in Presa Rodrigo Gómez in the Río Grande basin, Nuevo Léon in 1984. Tiemann et al. (2020) found live individuals of C. fluminea and C. largillierti at 10 sites in the Río Conchos (Río Grande basin), Chihuahua in May 2018.

Ríos Carrizal, Soto la Marina, etc. basins

Hillis and Mayden (1985) summarized the data to date on the presence of Corbicula in Mexico and the neotropics. In January 1984, they investigated various river systems along the Gulf Coast in northeastern Mexico for evidence of Corbicula and found populations of both the “white and purple forms” in the San Juan River (Río Grande basin), at el Castillo, Nuevo León, and an unnamed tributary of the Río Corona (Soto la Marina basin), 3 km S of Mex. Hwy. 101, Tamaulipas (Hillis & Mayden, 1985). However, they failed to find either form in the Río San Fernando, which lies between the Río San Juan and Río Soto la Marina basins. There is an unpublished record from the Río San Fernando at Mexico Highway 101/180 collected by A.L. Metcalf in May 1974 (UTEP 15126). The authors also found no evidence of Corbicula in Río Purificación, despite the presence of both species of Corbicula in the Río Corona branch of the Soto la Marina basin. Further, Hillis and Mayden (1985) found no evidence of the purple form of Corbicula south of the Río Soto la Marina basin, or of either form south of the Río Carrizal basin, even though they sampled at several sites in the ríos Pánuco, Tuxpan (= Pantepec), Nautla, Blanco, and Balsas. There are numerous records post-1985 in the Río Soto la Marina basin from Presa Vicente Guerrero and Arroyo San Felipe, the Río San Fernando in Tamaulipas, and the Río Pantepec, Veracruz, which lies between the Pánuco and Papaloapan (López-López et al., 2009).

Figure 1. Distribution of Corbicula species —Corbicula fluminea (form A; black dots) and Corbicula largillierti (form B; purple dots)— in Mexico and the Colorado and Río Grande river basins in the southern USA based upon our compilation of records as described in the Materials and methods section. These Corbicula records, including data sources, were archived in the Illinois Data Bank (https://doi.org/10.13012/B2IDB-9221608_V1).

Figure 2. The 2 Corbicula speciesin Mexico —Corbicula fluminea (Müller, 1774) (form A, left) and Corbicula largillierti (Philippi, 1844) (form B, right). Images modified from Tiemann et al. (2017).

Río Pánuco basin

Continuing south along the Gulf of Mexico coast, C. fluminea began showing up in the Río Pánuco basin from the Río Comandante, Tamaulipas in January 1990 (UF 159751; Counts, 1991), the Río Huichihuayán, San Luis Potosí in July 1993 (UF 211359; Benson & Williams 2021), and the Río Tempoal, Veracruz in February 1994 (INHS 89423). Rico-Sánchez et al. (2020) reported C. fluminea from 6 sites in the Río Pánuco basin in the Biosphere Reserve Sierra Gorda, Querétaro between February and July 2017. We (JST & KSC) collected Corbicula fluminea from 16 sites in the Río Pánuco basin, San Luis Potosí in 2017-2018.

Río Papaloapan basin

Torres-Orozco and Revueltas-Valle (1996) found several empty valves of C. fluminea in Laguna de Catemaco, Veracruz in 1992. Later, they confirmed the presence of C. fluminea at several localities along the southeastern shore of the lake: Las Margaritas, Ahuacapan, and Cuetzalapan in September 1994, which they attributed to dispersal by migratory birds (Torres-Orozco & Revueltas-Valle, 1996). Naranjo-García and Olivera-Carrasco (2014) reported C. fluminea from the Río Atoyac (Río Jamapa basin), ca. 16 km from Cordoba in August 1997 (CNMO 689). Ruelas-Inzunza et al. (2007) found C. fluminea further south in the Río Coatzacoalcos, Veracruz in 2005, and Naranjo-García and Olivera-Carrasco (2014) also reported it from the Río Coatzacoalcos in 2012 (CNMO 4009). Barba-Macías and Trinidad-Ocaña (2017) found C. fluminea at 7 sites in the Río Papaloapan basin in 2013.

Río Usumacinta basin

The first record of C. fluminea reported from the Río Usumacinta basin was from the Río Lacantún in Chiapas in 2007 and numerous other sites in or near the Reserva de la Biosfera Montes Azules in Chiapas and Tabasco from 2009-2022 (Barba-Macías & Trinidad-Ocaña, 2017; Naranjo-García & Olivera-Carrasco, 2014; Ramírez et al., 2022; CNMO Collection data). We also collected both C. fluminea and C. largillierti at 8 sites in the Río Usumacinta basin, Tabasco and Chiapas in 2019.

Pacific: Mesa Central & Balsas basins

Mesa Central and Balsas Region lies south of the Colorado and west of the Río Pánuco basins. There are numerous endorheic basins in this area (e.g., Llanos El Salado and Río Nazas). The area is largely drained by the Lerma-Santiago system. The Río Lerma mainstem is > 700 km long and empties into the Lago de Chapala, which is Mexico’s largest lake, and then into the Río Grande de Santiago, which drains into the Pacific. Comparably, the Río Balsas (also locally known as the Río Mezcala or Río Atoyac) has its headwaters in the western slope of the Continental Divide, southeast of the city of Puebla, and flows southwest where it empties into the Pacific Ocean at the border of Guerrero and Michoacán. This area is highly mountainous with the Sierra Madre Occidental reaching its southern limit here and the Río Balsas cutting through the Sierra Madre del Sur and Eje Volcánico Transversal. Corbicula fluminea first appeared along the Pacific Coast at Playa Novillero in Nayarit in 1969 (DMNH 92579; Table 2) and the Río Fuerte in Sinaloa in May 1971 (USNM 892340 and USNM 903657; Ramírez-Herrera & Urbano, 2014). There are numerous records of both C. fluminea and C. largillierti in the Mesa Central in the endorheic Nazas System, Armería, Atoyac (Balsas), Elota, Fuerte, and Río Grande de Santiago basins in the states of Durango, Guanajuato, Guerrero, Jalisco Michoacán, Morelos, Nayarit, Sinaloa, and Zacatecas. States (i.e., Baja California Sur and Yucatán) or areas with few or no records of Corbicula may be attributed to a lack of collecting or suitable habitat in those places.

Caribbean basin

There are odd records of both C. fluminea (DMNH 237279) and C. largillierti (DMNH 249472) from Cozumel, Quintana Roo in 1972. Whether they got to the island via humans, fish, or another method is unknown.

The biodiversity of some countries, like Mexico (Inoue et al., 2020; Kiser et al., 2022), is understudied and citizen scientists play an integral role in collecting data and aid in documenting new occurrences of invasive species (Barbato et al., 2021; Di Decco et al., 2021; Tiemann et al., 2022). This collaboration is critical in advancing our knowledge and conservation of our natural environment. However, as scientists, we must train and encourage citizen scientists to collect useful and verifiable data, as we discovered a misidentification error rate of ~ 10% and could not verify all Corbicula records submitted to iNaturalist due to photo quality or specimen orientation. We encourage future observers to take close-ups of both the external and internal sides of the shells to better aid in proper identification (i.e., similar to Fig. 2).

Our study was an attempt to summarize the known records of Corbicula taxa in Mexico. Given that several areas in Mexico are under sampled, it seems likely that Corbicula are established in additional areas (e.g., Pacific slope drainages) not reported here. We encourage colleagues to voucher specimens in natural history museums, as well as citizen scientists to take high quality photographs and upload them to iNaturalist with precise locality data when Corbicula are encountered, to help continue to document the spread of this invasive species in Mexico and Central America.

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Burden, E. Corona, J. de la Rosa Bolón, E. Gonzalez, P. Gonzalez, M. Hart, K. Inoue, N. Johnson, M. Larimore, T. Miller, A. Pieri, and A. Reyes-Gómez for assistance in the field; A. Benson for sharing known USGS Mexican Corbicula data; and SUP Kentucky and Kayak Huasteca, especially A. Koch, H. Warman, E. Aguado, C. Morones, and A. Reza, for providing priceless logistical support while in Mexico. E. Naranjo (CNMO); T. Pearce (CM); E. Shea and A. Kittle (DMNH); R. Bieler (FMNH); J. Slapcinsky (UF); J. Trimble (MCZ); J. Pfeiffer and Y. Villacampa (USNM); L. Frederick (NMMNH); N. Shoobs (OSUM); H. Chaney and V. Delnavaz (SBMNH); A. Bendict and C. Smith (SMBU); A. Czaja (UJMC); D. Ó Foighil and T. Lee (UMMZ); and E. Walsh and M. Zhuang (UTEP) for generously providing access to specimens and data under their care. T. Lee (UMMZ) helped confirm difficult identifications, and T. Contreras-Macbeth (Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos) shared their records of Corbicula in Mexico. Partial funding was provided by a U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service grant (F17AC01008), the Mohamed bin Zayed Species Conservation Fund, and the University of Illinois’ Mexican and Mexican American Students System Initiative.

References

Barba-Macías, E., & Trinidad-Ocaña, C. (2017). Nuevos registros de la almeja asiática invasora Corbicula fluminea (Bivalvia: Veneroida: Cyrenidae) en humedales de las cuencas Papaloapan, Grijalva y Usumacinta. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 88, 450–453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmb.2016.10.021

Barbato, D., Benocci, A., Guasconi, M., & Manganelli, G. (2021). Light and shade of citizen science for less charismatic invertebrate groups: quality assessment of iNaturalist nonmarine mollusc observations in central Italy. Journal of Molluscan Studies, 87, eyab033. https://doi.org/10.1093/mollus/eyab033

Benson, A. J., & Williams, J. D. (2021). Review of the invasive Asian clam Corbicula spp. (Bivalvia: Cyrenidae) distribution in North America, 1924–2019. Gainesville: U.S. Geological Survey. Scientific Investigations Report 2021–5001. https://doi.org/10.3133/sir20215001

Bieler, R., & Mikkelsen, P. M. (2019). Cyrenidae Gray, 1840, Chapter 35. In C. Lydeard, & K. S. Cummings (Eds.), Freshwater mollusk families of the World (pp. 187–192). Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Cohen, R. R. H., Dresler, P. V., Phillips, E. J. P., & Cory, R. L. (1984). The effect of the Asiatic clam, Corbicula fluminea, on phytoplankton of the Potomac River, Maryland. Limnology and Oceanography, 29, 170–180. https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.1984.29.1.0170

Contreras-Arquieta, A., & Contreras-Balderas, S. (1999). Description, biology, and ecological impact of the Screw Snail, Thiara tuberculata (Müller, 1774) (Gastropoda: Thiaridae) in Mexico. In R.Claudi, & J. H. Leach (Eds.), Nonindigenous freshwater organisms, vectors, biology, and impacts (pp. 151–160). Boca Raton: Lewis Press.

Counts III, C. L. (1986). The zoogeography and history of the invasion of the United States by Corbicula fluminea (Bivalvia: Corbiculidae). American Malacological Bulletin, Special Edition No., 2, 7–39.

Counts III, C. L. (1991). Corbicula (Bivalvia: Corbiculidae) Part 1. Catalog of fossil and recent nominal species. Part 2. Compendium of zoogeographic records of North America and Hawaii, 1924-1984. Tryonia, 21, 1–134.

Counts III, C. L., Villaz, J. R., & Gomez H, J. A. (2003). Occurrence of Corbicula fluminea (Bivalvia: Corbiculidae) in Panama. Journal of Freshwater Ecology, 18, 497–498.

Czaja, A., Becerra-López, J. L., Estrada-Rodríguez, J. L., Romero-Méndez, U., Cardoza-Martínez, G. F., Sáenz-Mata, J. et al. (2022). The Sabinas River basin in Coahuila, a new hotspot of molluscan biodiversity near Cuatro Ciénegas, Chihuahuan Desert, northern Mexico. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 93, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.22201/ib.20078706e.2022.93.3588

Czaja, A., Covich, A. P., Becerra-López, J. L., Cordero-Torres, D. G., & Estrada-Rodríguez, J. L. (2023). The freshwater mollusks of Mexico: can we still prevent their silent extinction? In R. W. Jones, C. P. Ornelas-García, R. Pineda-López, & F. Álvarez. (Eds.), Mexican Fauna in the Anthropocene (pp. 81–103). Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature Switzerland AG. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-17277-9

Davis, J. R. (1980). Species composition and diversity of benthic macroinvertebrates in the upper Río Grande,

Texas. Southwestern Naturalist, 25, 137–150.

Di Decco, G. J., Barve, V., Belitz, M. W., Stucky, B. J., Guralnick, R. P., & Hurlbert, A. H. (2021). Observing the observers: how participants contribute data to iNaturalist and implications for biodiversity science. Bioscience, 71, 1179–1188. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biab093

Dinger, E. C., Cohen, A. E., Hendrickson, D. A., & Marks, J. C. (2005). Aquatic invertebrates of Cuatro Cienegas, Coahuila, Mexico: natives and exotics. Southwestern Naturalist, 50,237–281.

Fox, R. O. (1970). Corbicula in Baja California. The Nautilus, 83, 145.

Fox, R. O. (1971). The Corbicula story, Chapter 3. Abstracts and Proceedings of the Fourth Annual Meeting of the Western Society of Malacologists, 4, 20.

Gatlin, M. R., Shoup, D. E., & Long, J. M. (2013). Invasive Zebra mussels (Driessena polymorpha) and Asian clams (Corbicula fluminea) survive gut passage of migratory fish species: implications for dispersal. Biological Invasions, 15, 1195–1200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-012-0372-0

Gutiérrez-Galindo, E. A., Flores-Muñoz, G., & Villaescusa-Celaya, J. (1988). Chlorinated hydrocarbons in Molluscs of the Mexicali Valley and upper Gulf of California. Ciencias Marinas, 14, 91–113. https://doi.org/10.7773/cm.v14i3.599

Haag, W. R. (2019). Reassessing enigmatic mussel declines in the United States. Freshwater Mollusk Biology and Conservation, 22, 43–60. https://doi.org/10.31931/fmbc.v22

i2.2019.43-60

Haponski, A. E., & Ó Foighil, D. (2019). Phylogenomic analyses confirm a novel invasive North American Corbicula (Bivalvia: Cyrenidae) lineage. PeerJ, 7, e7484. https://10.7717/peerj.7484

Hillis, D. M., & Mayden, R. L. (1985). Spread of the Asiatic clam Corbicula (Bivalvia: Corbiculacea) into the New World tropics. Southwestern Naturalist, 30, 454–456. https://doi.org/10.2307/3671285

Hoagland, K. E. (1986). Unsolved problems and promising approaches in the study of Corbicula. American Malacological Bulletin, Special Edition No., 2, 203–209.

iNaturalist. (2023). Naturalist community: Observations of Corbicula from Mexico. Retrieved on 20 April 2023 from: www.iNaturalist.org

Inoue, K., Cummings, K. S., Tiemann, J. S., Miller, T. D., Johnson, N. A., Smith, C. H. et al. (2020). A new species of freshwater mussel in the genus Popenaias Frierson, 1927, from Gulf coastal rivers of central Mexico (Bivalvia: Unionida: Unionidae) with comments on the genus.

Zootaxa, 4816, 457–490. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.

4816.4.3

Isom, B. G. (1986). Historical review of Asiatic Clam (Corbicula) invasion and biofouling of waters and industries in the Americas. American Malacological Bulletin, Special Edition No., 2, 1–5.

Kiser, A. H., Cummings, K. S., Tiemann, J. S., Smith, C. H., Johnson, N. A., López, R. R. et al. (2022). Using a multi-model ensemble approach to determine biodiversity hotspots with limited occurrence data in understudied areas: an example using freshwater mussels in México. Ecology and Evolution, 12, e8909. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.8909

Lee, T., Siripattrawan, S., Ituarte, C., & Ó Foighil, D. (2005). Invasion of the clonal clams: Corbicula lineages in the New World. American Malacological Bulletin, 20, 113–122.

López, E., Garrido-Olvera, L., Benavides-González, F., Blanco-Martínez, Z., Pérez-Castañeda, R., Sánchez-Martinez, J. G. et al. (2019). New records of invasive mollusks Corbicula fluminea (Müller, 1774), Melanoides tuberculata (Müller, 1774) and Tarebia granifera (Lamarck, 1816) in the Vicente Guerrero Reservoir, Mexico. Bioinvasions Records, 8, 640–652. https://doi.org/10.3391/bir.2019.8.3.21

López-López, E., Sedeño-Díaz, J. E., Vega, P. T., & Oliveros, E. (2009). Invasive mollusks Tarebia granifera Lamarck, 1822 and Corbicula fluminea Müller, 1774 in the Tuxpam and Tecolutla rivers, Mexico: spatial and seasonal distribution patterns. Aquatic Invasions, 4, 435–450. https://doi.org/10.3391/ai.2009.4.3.2

McMahon, R. F. (1999). Invasive characteristics of the freshwater bivalve Corbicula fluminea. In R. Claudi, & J. H. Leach (Eds.), Nonindigenous freshwater organisms, vectors, biology, and impacts (pp. 315–343). Boca Raton: Lewis Press.

McMahon, R. F. (2002). Evolutionary and physiological adaptations of aquatic invasive animals: r selection versus resistance. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 59, 1235–1244. https://doi.org/10.1139/f02-105

Minchin, D., & Boelens, R. (2018). Natural dispersal of the introduced Asian Clam Corbicula fluminea (Müller, 1774) (Cyrenidae) within two temperate lakes. Bioinvasions Records, 7, 259–268. https://doi.org/10.3391/bir.2018.7.3.06

Morton, B. (1986). Corbicula in Asia –an updated synthesis. American Malacological Bulletin, Special Edition No., 2, 113–124.

Naranjo-García, E., & Castillo-Rodríguez, Z. G. (2017). First inventory of the introduced and invasive mollusks in Mexico. The Nautilus, 131, 107–126.

Naranjo-García, E., & Meza-Meneses, G. (2000). Moluscos. In G. de la Lanza-Espino, S. Hernández-Pulido, & J. L. Carbajal-Pérez (Eds.), Organismos indicadores de la calidad del agua y de la contaminación (bioindicadores) (pp. 309–404). Cd. de México: Editorial Plaza y Valdés S.A. de C. V.

Naranjo-García, E., & Olivera-Carrasco, M. T. (2014). Moluscos dulceacuícolas introducidos e invasores. In R. Mendoza, & P. Koleff (Coords.), Especies acuáticas invasoras en México (pp. 337–345). Cd. de México: Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad.

Pigneur, L. M., Etoundi, E., Aldridge, D. C., Marescaux, J., Yasuda, N., & Van Doninck, K. (2014). Genetic uniformity and long-distance clonal dispersal in the invasive androgenetic Corbicula clams. Molecular Ecology, 23, 5102–5116. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.12912

Pigneur, L. M., Falisse, E., Roland, K., Everbecq, E., Deliège, J. F., Smitz, J. S. et al. (2014). Impact of invasive Asian clams, Corbicula spp., on a large river ecosystem. Freshwater Biology, 59, 573–583. https://doi.org/10.1111/fwb.12286

Ramírez, C., Barba, R., Caspeta, J. M., Córdova, F., Espinosa, H., Larre, S. et al. (2022). Biota acuática de la cuenca media del río Lacantún, Chiapas y la importancia del monitoreo de largo plazo. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 93, e934844. https://doi.org/10.22201/ib.20078706e.2022.93.4844

Ramírez-Herrera, M., & Urbano, B. (2014). Moluscos invasores de México. Conabio. Biodiversitas, 112, 6–9.

Rico-Sánchez, A. E., Sundermann, A., López-López, E., Torres-Olvera, M. J., Mueller, S., & Haubrock, P. (2020). Biological diversity in protected areas: not yet known but already threatened. Global Ecology and Conservation, 22, e01006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2020.e01006

Ruelas-Inzunza, J., Gárate-Viera, Y., & Páez-Osuna, F. (2007). Lead in clams and fish of dietary importance from Coatzacoalcos estuary (Gulf of Mexico), an industrialized tropical region. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 79, 508–513. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00128-007-9285-5

Ruelas-Inzunza J., Spanopoulos-Zarco, P., & Páez-Osuna, F. (2009). Cd, Cu, Pb and Zn in clams and sediments from an impacted estuary by the oil industry in the southwestern Gulf of Mexico: concentrations and bioaccumulation factors. Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part A, 44, 1503–1511. https://doi.org/10.1080/10934520903263280

Sabaj, M. H. (2020). Codes for Natural History Collections in Ichthyology and Herpetology. Copeia, 108, 593–669. https://doi.org/10.1643/asihcodons2020

Smith, L. M., Vanglider, L. D., Hoppe, R. T., Morreale, S. J., & Brisbin Jr, I. L. (1986). Effect of diving ducks on benthic food resources during winter in South Carolina, U.S.A. Wildfowl, 37, 136–141.

Sousa, R., Antunes, C. & Guilhermino, L. (2008). Ecology of the invasive Asian clam, Corbicula fluminea (Müller, 1774) in aquatic ecosystems: an overview. Annales de Limnologie – International Journal of Limnology, 44, 85–94. https://doi.org/10.1051/limn:2008017

Thompson, C. M., & Sparks, R. E. (1977). Improbability of dispersal of adult Asiatic clams, Corbicula manilensis, via the intestinal tract of migratory waterfowl. American Midland Naturalist, 98, 219–223. https://doi.org/10.2307/2424727

Tiemann, J. S., Haponski, A. E., Douglass, S. A., Lee, T., Cummings, K. S., Davis, M. A. et al. (2017). First record of a putative novel invasive Corbicula lineage discovered in the Illinois River, Illinois, USA. Bioinvasions Records, 6, 159–166. https://doi.org/10.3391/bir.2017.6.2.12

Tiemann, J. S., Inoue, K., Rodríguez-Pineda, J. A., Hart, M., Cummings, K. S., Naranjo-García, E. et al. (2020). Status of freshwater mussels (Unionidae) of the Río Conchos basin, Chihuahua, Mexico. Southwestern Naturalist, 64, 180–186. https://doi.org/10.1894/0038-4909-64.3-4.180

Tiemann, J. S., Stodola, A. P., Douglass, S. A., Vinsel, R. M., & Cummings, K. S. (2022). Nonindigenous aquatic mollusks in Illinois. Illinois Natural History Survey Bulletin, 43, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.21900/j.inhs.v43.862

Torres-Orozco, R., & Revueltas-Valle, E. (1996). New southernmost record of the Asiatic clam Corbicula flumi-

nea (Bivalvia: Corbiculidae), in Mexico. Southwestern Naturalists, 41, 60–61.

Trinidad-Ocaña, C., Juárez-Flores, J., Sánchez, A. J., & Barba-Macías, E. (2018). Diversidad de moluscos y crustáceos acuáticos en tres zonas en la cuenca del río Usumacinta, México. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 89 (Suppl.), S65–S78. https://doi.org/10.22201/ib.20078706e.2018.0.2387

Voelz, N. J., McArthur, J. V., & Rader, R. B. (1998). Upstream mobility of the Asiatic clam Corbicula fluminea: identifying potential dispersal agents. Journal of Freshwater Ecology, 13, 39–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/02705060.1998.9663589