José Alan Herrera-García a, Mahinda Martinez a, b, *, Pilar Zamora-Tavares c, Ofelia Vargas c, Luis Hernández-Sandoval a, b

a Universidad Autónoma de Querétaro, Facultad de Ciencias Naturales, Av. de las Ciencias, s/n, 76230 Juriquilla, Querétaro, Mexico

b Universidad Autónoma de Querétaro, Facultad de Ciencias Naturales, Biología, Laboratorio Nacional de Identificación y Caracterización Vegetal, Av. de las Ciencias, s/n, 76230 Juriquilla, Querétaro, Mexico

c Universidad de Guadalajara, Centro Universitario de Ciencias Biológicas y Agropecuarias, Instituto de Botánica, Departamento de Botánica y Zoología, Laboratorio Nacional de Identificación y Caracterización Vegetal, Av. Ing. Ramón Padilla Sánchez, 45200 Zapopan, Jalisco, Mexico

*Corresponding author: mahinda@uaq.mx (M. Martínez)

Received: 20 May 2024; accepted: 19 February 2025

Abstract

Some bromeliads form a compact rosette that accumulates detritus and water, known as phytotelma. The phytotelma is a lentic ephemeral aquatic environment that forms diverse communities with complex trophic levels. Pseudalcantarea grandis, a saxicolous plant, forms a phytotelma. To understand the importance of P. grandis as a eukaryotic diversity reservoir in arid zones, we collected water samples from 5 plants growing in a dry canyon in Zimapán, Hidalgo, Mexico. We analyzed them through metabarcoding of the ITS1 (Internal Transcribed Spacer) and the partial 5.8S gene. We used the Ion Torrent PGM platform for the sequencing, and the taxonomic assignation for the amplicons was made with BLAST in Genbank at NCBI. We found 26 phyla and 543 genera, 80% of which belonged to Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, Blastocladiomycota Chytridiomycota, Glomeromycota, Mucoromycota, and Zoopagomycota phyla. The remaining 20% was composed of 19 phyla belonging to other kingdoms. Photosynthetic organisms were represented by the phyla Bacillariophyta, Charophyta, Chlorophyta, and Ochrophyta. The vascular plants do not live in the tank but constitute the debris sustaining the large number of decomposers. The trophic levels in the tank were detritus, micro- and macro-decomposers, filter feeders, photosynthesizers, micro-predators, aquatic volume predators, surface predators, and parasites.

Keywords: Aquatic; Ephemeral; Arid zone; Phytotelma

Diversidad de eucariotes y niveles tróficos dentro de la bromelia tanque Pseudalcantarea grandis en una zona árida detectados por metabarcoding de ADN ambiental

Resumen

Algunas bromelias forman rosetas compactas que acumulan detritus y agua. Esta acumulación se conoce como fitotelma, un hábitat acuático léntico y efímero con comunidades diversas y niveles tróficos complejos. Psedalcantarea grandis es una planta saxícola y forma un fitotelma. Para entender la importancia de P. grandis como reservorio de diversidad acuática en una zona árida, colectamos muestras de agua de 5 plantas en un cañón de Zimapán, Hidalgo, México y las analizamos por metabarcoding del ITS1 (Internal Transcribed Spacer) y una región parcial del gen 5.8S. La secuenciación se hizo en la plataforma Ion Torrent PGM. Asignamos la identidad taxonómica de los amplicones utilizando BLAST de Genbank. Encontramos 26 phyla y 543 géneros, 80% pertenecen a los phyla fúngicos Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, Blastocladiomycota Chytridiomycota, Glomeromycota, Mucoromycota, y Zoopagomycota. El 20% restante está compuesto por 19 phyla de otros reinos. Los organismos fotosintéticos estuvieron representados por los phyla Bacillariophyta, Charophyta, Chlorophyta y Ochrophyta. Otros organismos fotosintéticos que corresponden a plantas vasculares no viven dentro del tanque, pero forman la hojarasca que mantiene a los descomponedores. Los niveles tróficos en el tanque fueron detritus, micro y macrodescomponedores, filtradores, fotosintetizadores, microdepredadores, depredadores del volumen de agua, depredadores de superficie y parásitos.

Palabras clave: Acuático; Efímero; Zona árida; Fitotelma

Introduction

The Bromeliaceae family is comprised of almost 3,700 species distributed mostly in tropical areas of the Americas (Gouda et al., 2024). They are herbaceous perennial monocots with leaves arranged in rosettes, many of which are epiphytes (Ramírez-Murillo et al., 2004; Rzedowski, 2006). There are 442 species in Mexico (Espejo-Serna & López-Ferrari, 2018) that frequently grow in nutrient and mineral-deficient environments (Bernal et al., 2006; Ramírez-Murillo et al., 2004). Some species form compact rosettes with absorbent trichomes in their interior that allow the accumulation of solids rich in nutrients and water, known as phytotelma (Benzing, 2000; Goffredi et al., 2011).

Phytotelmata are lentic aquatic environments, mostly ephemeral that last less than 3 months (Mogi, 2004). They are freshwater habitats for diverse communities including viruses, Archaea, and bacteria (Brouard et al., 2013, Goffredi et al., 2011). Among the eukaryotes, aquatic mosses, green algae, diatoms, protists, fungi, insects, amphibians, and crustaceans have been documented (Benzing, 2000; Brandt et al., 2017; Kitching, 2001; Ramos & do Nascimento Moura, 2019; Rodríguez-Núñez et al., 2018; Simão et al., 2020).

Bromeliads that form phytotelma accumulate essential mineral elements, which are the main nitrogen source for the plant (Kitching, 2001). The presence of detritivores and predators is related to the nitrogen concentration in the leaves. Predators increase nutrient flux from the leaf litter of nearby plants to the bromeliad (Benzing & Renfrow, 1974; Ngai & Srivastava, 2006; Nievola et al., 2001; Takahashi & Mercier, 2011).

Unlike terrestrial and aquatic communities in which plants and algae are the main nutrient resources, in the phytotelma leaf litter and invertebrate remains play that role. In trophic networks inside the phytotelma, protists and rotifers are considered as micro-predators that also consume organic particles. Macroinvertebrates can consume the detritus, filter feeders, aquatic predators, and surface predators, whereas bacteria and fungi are the main decomposers that obtain energy directly from the detritus (Brouard et al., 2012; Mogi, 2004).

Gomes et al. (2015) characterized the enzymatic activity of the fungal community inside the bromeliad tank of Vriesea minarum in Brazil. Using cultivation techniques they identified 36 species, 22 of which were Basidiomycota and 14 were Ascomycota. The most relevant genera were Cryptococcus, Candida, and Aureobasidium. These organisms contain enzymes that degrade vegetal material.

Nutrient intake for the plant is further facilitated by insects (Ngai & Srivastava, 2006). For example, odonatan larvae ingest detritivores, contributing to the nitrogen cycle within the bromeliad by defecating. Leachates from defecation release nitrogen in a form available to the bromeliad and create a suitable niche for other microorganisms providing substrata (Benzing & Renfrow, 1974).

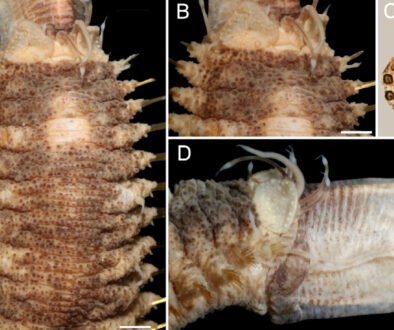

Pseudalcantarea grandis (Schltdl.) Pinzón & Barfuss (Fig. 1A) is a saxicolous tank bromeliad that reaches 2.5 m in height and forms a highly ramified inflorescence in March and April. It is distributed from Central Mexico (Guanajuato, Querétaro, Hidalgo) toward the south (Puebla, Oaxaca, and Chiapas) and into Honduras. It is considered a MegaMexico II endemic species (Espejo-Serna et al., 2010). At the locality of Las Adjuntas, in Hidalgo, the plant is known as “tinaja”, “jarilla”, and “soluche de agua” because its tank can store water. The species grows in crags of the main rivers in the northeastern portion of the region known as Bajío. It grows at elevations ranging from 400 to 1,600 m asl (Espejo-Serna et al., 2010; Rzedowski, 2006).

Figure 1. Life form and habitat of the tank bromeliad Pseudalcantarea grandis. A, Plant and inflorescence of Pseudalcantarea grandis; B, Las Angosturas Canyon crags where the tank bromeliad grows.

Metabarcoding studies describing the communities associated with phytotelma have mostly focused on specific groups such as vertebrates (Brozio et al., 2017), ciliates (Simão et al., 2017), or bacteria (Louca et al., 2017; Rodríguez-Núñez et al., 2018). In Pseudalcantarea grandis, 297 bacteria genera were found, with Proteobacteria (37%), Actinobacteria (19%), and Firmicutes (15%) comprising the highest percentage (71%). The main metabolic functions were aerobic chemoheterotrophy and fermentation. However, rare biosphere bacteria were also found, which could favor micro-ecosystem resilience and resistance (Herrera-García et al., 2022). Comprehensive sequencing of the eukaryotic diversity inside tank bromeliads has been performed in tropical zones (Simão et al., 2020), but not arid areas. The objectives of our study were to describe the eukaryotic diversity in Pseudalcantarea grandis phytotelma to understand which vascular plants form the litter, and to infer the putative trophic levels of the phytotelmata in an arid zone.

Materials and methods

Water samples were collected during the 2018 rainy season at Las Angosturas Canyon, Zimapán, Hidalgo, Mexico (20°50.933’ N, 99°26.7’ W, 900 m asl, see Herrera-García et al. [2022] for a location map) within the Queretano-Hidalguense arid zone, which has been described as a high-diversity and endemicity area (Hernández-Magaña et al., 2017; Hernández & Bárcenas, 1995; Rojas et al., 2013). This arid zone is considered the southernmost portion of the Chihuahuan Desert floristic province. It consists mostly of arid valleys and depressions surrounded by mountains (Hernández & Gómez-Hinostrosa, 2005).

Las Angosturas Canyon is approximately 12 km long with a mixture of xerophytic scrub and tropical deciduous forest (Fig. 1B). Bromeliads grow on vertical crags with different amounts of the surrounding vegetation. Therefore, the tanks are frequently filled with leaf litter. We selected individuals that were accessible enough to be collected by a rappel and were more than 50 cm in diameter. The associated plants are listed in Table 1. To collect the water inside the bromeliads we used Nest® cell scrapers to scratch the inside of each tank, and the water in the bromeliads was vigorously shaken to obtain a homogeneous sample. Water volumes of 50 to 100 ml were collected using 10 ml sterile serological pipettes. The samples were stored in 50 ml conical Falcon tubes, transported on dry ice, and stored at -79 °C until processing. Physicochemical water parameters were not determined.

Table 1

Las Angosturas Canyon floristic inventory. Plants directly above the sampled individuals are noted in the second column. Vouchers and photographs are noted in the third column.

| Family | Species | Association | Reference at QMEX |

| Amaryllidaceae | Zephyranthes clintiae Traub | A. Herrera 30 | |

| Amaryllidaceae | Zephyranthes concolor (Lindley) Bentham & Hook. | A. Herrera 7 | |

| Anacardiaceae | Rhus terebinthifolia Schltdl. & Cham. | A. Herrera 21 | |

| Anacardiaceae | Pseudosmodingium virletii (Baill.) Engl. | L. Hernández 5029 | |

| Apocynaceaea | Asclepias curassavica L. | A. Herrera 20 | |

| Apocynaceaea | Vallesia glabra (Cav.) Link | A. Herrera 4 | |

| Arecaceae | Brahea dulcis (Kunth) Mart. | Photographic record | |

| Asparagaceae | Agave xylonacantha Salm-Dyck | surrounding | A. Vega 50 |

| Asparagaceae | Dasylirion longissimum Lem. | L. Hernández 4511 | |

| Asparagaceae | Yucca filifera Chab. | L. Hernández 4828 | |

| Asparagaceae | Yucca queretaroensis Piña | Photographic record | |

| Asteraceae | Baccharis salicifolia (Ruiz y Pav.) Pers. | M. Martínez 6056 | |

| Asteraceae | Cirsium sp. | A. Herrera ND | |

| Asteraceae | Gnaphalium luteo-album L. | A. Herrera ND | |

| Asteraceae | Gochnatia hypoleuca (DC.) A. Gray | surrounding | A. Herrera ND |

| Bignoniaceae | Tecoma stans (L.) Juss. | Photographic record | |

| Boraginaceae | Cordia boissieri A. DC. | M. Martínez 7144 | |

| Bromeliaceae | Hechtia glomerata Zucc. | surrounding | S. Zamudio 14469 |

| Bromeliaceae | Hechtia tillandsioides (André) L. B. Smith | surrounding | Photographic record |

| Table 1. Continued | |||

| Family | Species | Association | Reference at QMEX |

| Bromeliaceae | Pseudalcantarea grandis (Schltdl.)Pinzón & Barfuss | A. Herrera 1 | |

| Bromeliaceae | Tillandsia recurvata L. | surrounding | M. Martínez 8220 |

| Burseraceae | Bursera morelensis Ram. | surrounding | Photographic record |

| Cactaceae | Astrophytum ornatum (DC.) Britton & Rose | Photographic record | |

| Cactaceae | Cylindropuntia imbricata (Haw.) F. M. Knuth ssp. cardenche (Griffiths) U. Guzmán | A. Herrera 12 | |

| Cactaceae | Coryphanta sp. | Photographic record | |

| Cactaceae | Echinocereus pentalophus Lem. | Photographic record | |

| Cactaceae | Echinocactus platyacanthus Link & Otto | M. Figueroa 12 | |

| Cactaceae | Ferocacutus histrix (DC.) G.E.Linds. | Photographic record | |

| Cactaceae | Mammilaria elongata DC. | surrounding | Photographic record |

| Cactaceae | Mammillaria longimamma DC. | Photographic record | |

| Cactaceae | Myrtillocactus geometrizans (Mart. ex Pfeiff.) Console | surrounding | Photographic record |

| Cactaceae | Neobuxbaumia polylopha (DC.) Backeberg | Photographic record | |

| Cactaceae | Opuntia imbricata (Haw.) F. M. Kunth | Photographic record | |

| Cactaceae | Opuntia microdasys (Lehm.) Pfeiff. | Photographic record | |

| Cactaceae | Opuntia rastrera F.A.C. Weber | surrounding | Photographic record |

| Cactaceae | Stenocereus queretaroensis (F.A.C.Weber ex Mathes.) Buxb. | Photographic record | |

| Cactaceae | Strombocactus disciformis (DC.) Britton & Rose | Photographic record | |

| Cannabaceae | Celtis pallida Torr. | A. Herrera 2 | |

| Capparaceae | Capparis incana Kunth | A. Herrera 5 | |

| Convolvulaceae | Ipomoea rzedowskii E. Carranza | A. Herrera 17 | |

| Crassulaceae | Echeveria secunda Booth | surrounding | A. Herrera 26 |

| Crassulaceae | Pachyphytum sp. | A. Herrera ND | |

| Crassulaceae | Sedum sp. | surrounding | A. Herrera ND |

| Euphorbiaceae | Cnidoscolus tubulosus (Muell. Arg.) I.M. Johnst. | A. Herrera 9 | |

| Euphorbiaceae | Acalypha monostachya Cav. | A. Herrera 15 | |

| Euphorbiaceae | Croton ciliato-glandulifer Ort. | L. Hernández 5029 | |

| Euphorbiaceae | Jatropha dioica Sessé ex Cerv. | A. Herrera ND | |

| Euphorbiaceae | Ricinus communis L. | A. Herrera ND | |

| Fabaceae | Acacia berlandieri Benth. | surrounding | Photographic record |

| Fabaceae | Albizia occidentalis Brandegee | Photographic record | |

| Fabaceae | Bauhinia sp. | Photographic record | |

| Fabaceae | Lysiloma microphylla Bentham | A. Herrera 36 | |

| Fabaceae | Mimosa leucaenoides Bentham | surrounding | Photographic record |

| Fabaceae | Mimosa martindelcampoi F. G. Medrano | Photographic record | |

| Fabaceae | Mimosa puberula Bentham | A. Herrera 3 | |

| Fabaceae | Pithecellobium dulce (Roxb.) Bentham | Photographic record | |

| Fabaceae | Neltuma laevigata (Humb. & Bonpl. ex Willd.) Britton & Rose | M. Martínez ND | |

| Fabaceae | Vachellia farnesiana (L.) Willd. & Arn. | A. Herrera 10 | |

| Table 1. Continued | |||

| Family | Species | Association | Reference at QMEX |

| Fouquieriaceae | Fouquieria splendens Engelm. | surrounding | Photographic record |

| Lentibulariaceae | Pinguicula aff. moctezumae Zamudio & R.Z. Ortega | Photographic record | |

| Lythraceae | Heimia salicifolia (Kunth) Link | A. Herrera 13 | |

| Onagraceae | Hauya elegans DC. | surrounding | A. Herrera 14 |

| Malpighiaceae | Mascagnia macroptera (Moc. & Sessé ex DC.) Nied. | A. Herrera 8 | |

| Malvaceae | Pseudobombax ellipticum (Kunth) Dugand | A. Herrera ND | |

| Malvaceae | Malvaviscus arboreus Cav. | M. Martínez 5317 | |

| Myrtaceae | Psidium guajava L. | surrounding | Photographic record |

| Papaveraceae | Argemone ochroleuca Sweet | M. Martínez 6713 | |

| Plantaginaceae | Rusellia polyedra Zucc. | A. Herrera 27 | |

| Platanaceae | Platanus mexicana Moric. | A. Herrera 16 | |

| Poaceae | Arundinaria sp. | A. Herrera ND | |

| Poaceae | Cenchrus sp. | A. Herrera ND | |

| Poaceae | Cynodon dactylon (L.) Pers. | M. Martínez 3197 | |

| Poaceae | Eragrostis sp. | E. Carranza 5251 | |

| Primulaceae | Samolus ebracteatus Kunth | A. Herrera 11 | |

| Pteridaceae | Argyrochosma formosa (Liebm.) Windham | A. Herrera 23 | |

| Pteridaceae | Notholaena affinis (Mett.) T. Moore | A. Herrera 24 | |

| Pteridaceae | Notholaena jacalensis Pray | A. Herrera 25 | |

| Pteridaceae | Pellaea sp. | A. Herrera 34 | |

| Ranunculaceae | Clematis drummondii Torr. & A.Gray | M. Martínez 4434 | |

| Rhamnaceae | Karwinskia subcordata Schlecht. | A. Herrera 22 | |

| Rubiaceae | Nernstia mexicana (Zucc. & Mart. ex DC.) Urb. | A. Herrera 32 | |

| Salicaceae | Neopringlea integrifolia (Hemsl.) S. Watson | A. Herrera 19 | |

| Salicaceae | Salix humboldtiana Willd. | Photographic record | |

| Sapindaceae | Dodonaea viscosa (L.) Jacq. | A. Herrera ND | |

| Sapindaceae | Sapindus saponaria L. | A. Herrera ND | |

| Sapindaceae | Serjania sp. | A. Herrera ND | |

| Selaginellaceae | Selaginella lepidophylla (Hook. & Grev.) Spring. | surrounding | Photographic record |

| Selaginellaceae | Selaginella ribae Valdespino | A. Herrera 29 | |

| Selaginellaceae | Selaginella selowii Hieron. | A. Herrera 28 | |

| Solanaceae | Datura inoxia Miller | V. Martínez 1 | |

| Solanaceae | Nicotiana glauca Graham | Photographic record | |

| Solanaceae | Nicotiana trigonophylla Dunal | O. García 434 | |

| Solanaceae | Physalis cinerascens (Dunal) Hitch. | L. Hernández 3769 | |

| Solanaceae | Physalis philadelphica Lam. | A. Herrera 38 | |

| Solanaceae | Solanum lycopersicon L. | Photographic record | |

| Taxodiaceae | Taxodium mucronatum Ten. | M. Martínez 3237 | |

| Urticaceae | Urera sp. | H. Rubio 302 | |

| Zygophyllaceae | Morkillia acuminata Rose & Painter | surrounding | A. Herrera 18 |

DNA extraction

Water samples were homogenized and 100 ml was filtered through a 0.22 µm Millipore® nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was frozen and macerated in liquid nitrogen. We extracted total DNA using the QIAmp DNA Extraction® kit following the manufacturer’s instructions by duplicate to obtain pseudoreplicates and verify reproducibility. DNA quality and concentration were evaluated using NanoDrop® spectrophotometry.

Amplicon sequencing

To characterize eukaryotic diversity, we amplified a portion of the 5.8 S Internal Transcibed Spacer (ITS) with the ITS1 and ITS2 primers designated by White et al. (1990). The PCR reaction consisted of a final volume of 25 µl, that contained 2 mM of dNTP´s, 2mM µl of each primer, 0.4% DMSO, 0.4 % BSA, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 1.2 mM Buffer, 1.25 U Platinum Taq, 60ng/µl DNA and H2O. Thermocycler conditions were an initial step at 95 °C for 3 min, followed by 30 cycles at 95 °C for 1 min; 52 °C, 45 s, and 72 °C, 2 min, with a final extension step at 72 °C for 5 min. Amplicons were purified with Agencourt® AMPure® XP.

To construct the libraries, we used the Ion Plus Fragment Library kit. The presence, size, and concentration of the fragment were analyzed using Bioanalyzer 2100 with high-sensitivity DNA assay (Agilent). Libraries were quantified using real-time PCR to obtain an equimolar dilution factor to mix the 3 libraries. The template was prepared using a PCR emulsion in the Ion One Touch 2 System (Life Technologies) and quantified by fluorometry in Qubit® 3.0 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Finally, the template was loaded onto the PGM 318TM chip using the 400-pair base fragment sequencing kit, according to the Ion PGM™ Hi‑Q™ View Sequencing Kit protocol.

We sampled the vascular plants growing at the canyon, directly above the bromeliad, and also the surrounding vegetation. Voucher specimens were deposited at QMEX herbarium. We compared the similarity of the plant inventory obtained by sequencing against the floristic list obtained by field sampling through a Sorensen coefficient analysis at the family level.

Sequencing quality was evaluated using the FastQC program. Sequences were filtered by the quality value of Phred > 20. We selected sequences larger than 100 bp in the CLC Genomic Workbench v.11.01 (QIAGEN Bioinformatics, Aarhus, Denmark) platform. In the Microbial Genomics module application, we performed an analysis based on the amplicons to aggregate the sequences in operational taxonomic units (OTUs) considering only 99% similarity among them. We deleted unique reads and chimeras. Taxonomic assignation of the amplicons was performed with BLAST in 2023 via the Genbank at NCBI database (Altschul et al., 1990). Over 90% of the OTUs had identity percentages higher than 95% and only 54 OTUs had lower percentages, ranging from 75 to 80%. We manually reviewed them and corroborated the genus of each one. Since BLAST provides determinations at the genus and species levels, we used MEGAN Community Edition V. 6.24.4 to assign kingdom, phylum, class, order, and family. We loaded the BLAST results using the lowest basal common ancestor assignation algorithm (LCA). The analysis is based on the taxonomic hierarchies recognized by NCBI and the results are displayed as a phylogenetic tree that allows simple observation of taxonomic diversity (Huson et al., 2016). We manually reviewed the classifications and to corroborate the taxonomic assignations we used the classification proposed by Simpson (2006) for plants, and Tree of Life (2022) for the other eukaryotic marine taxa (such as Cnidaria). The OTUs at the genus level were used to define the total eukaryotic group diversity present in our sample.

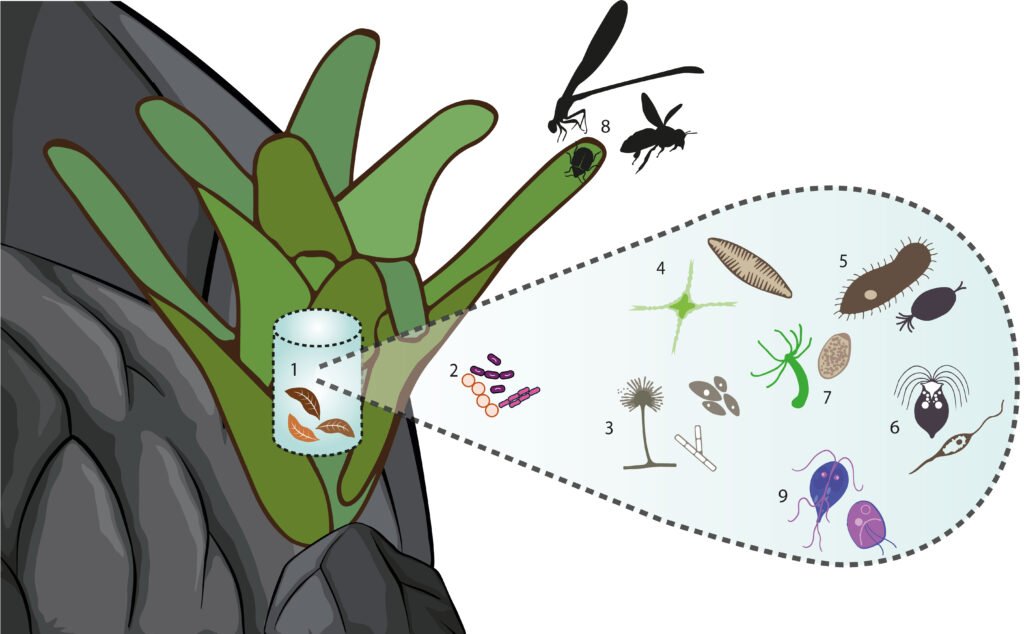

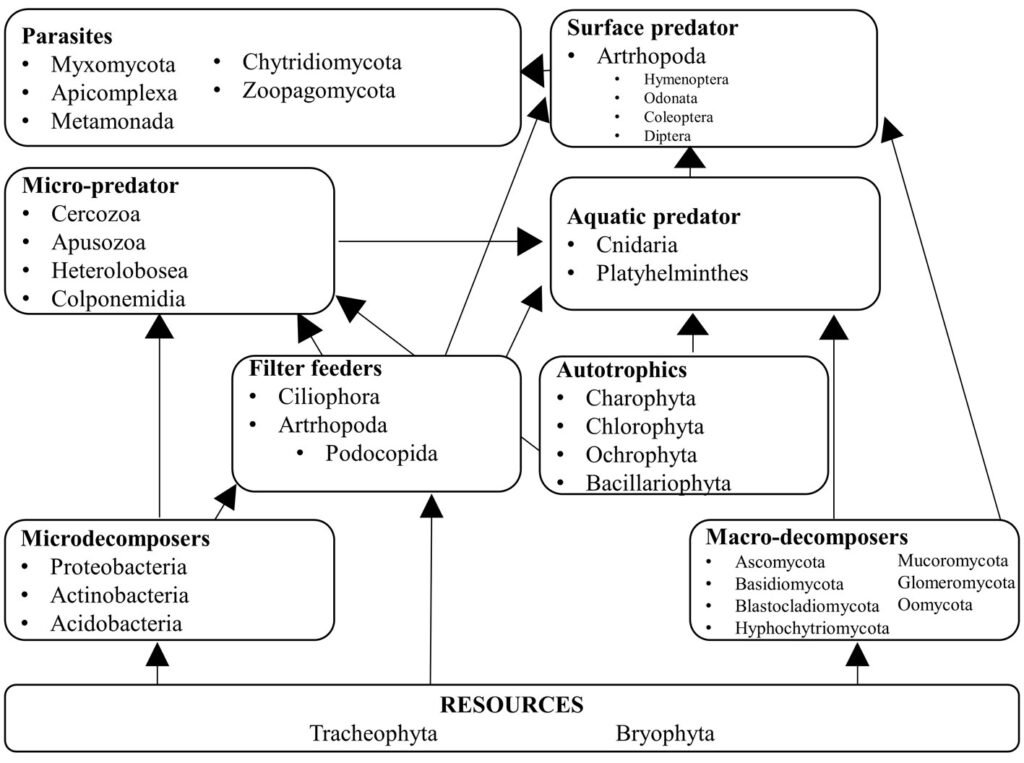

We assigned the ecological function of each genus following the criteria of Mogi (2004) and Brouard et al. (2012). We considered 9 categories: 1) detritus formed by leaf litter and vegetal matter that serves as the main resource for the trophic network; 2) micro decomposers integrated by bacteria (Herrera-García et al., 2022); 3) macro decomposers formed by saprobiotic fungi; 4) filter feeders that use small particles including microorganisms that are in turn consumed by aquatic and surface predators; 5) photosynthetic organisms that require sunlight and serve as food for predators; 6) micro predators that feed on photosynthetic organisms, filter feeders, and micro-decomposers; 7) aquatic predators which are macroinvertebrates that live in the water column and feed mostly on algae and bacteria; 8) surface predators which are restricted to the uppermost portion of the water column and feed on protists, bacteria, and algae; and 9) parasites which are obligate vertebrate parasites that use arthropods as vectors.

Results

The 5 sampled plants had volumes that varied from 50 to 100 ml. The 2 pseudoreplicates were compared and considered as a single pool due to the similarity of the resulting OTUs. We obtained a total of 3,276,538 lectures. After quality and size filtration, the number of useful lectures was reduced to 1,284,998 representing a total of 23,948 OTUs, 762 of which could not be assigned to the species or genus taxonomic category provided by BLAST.

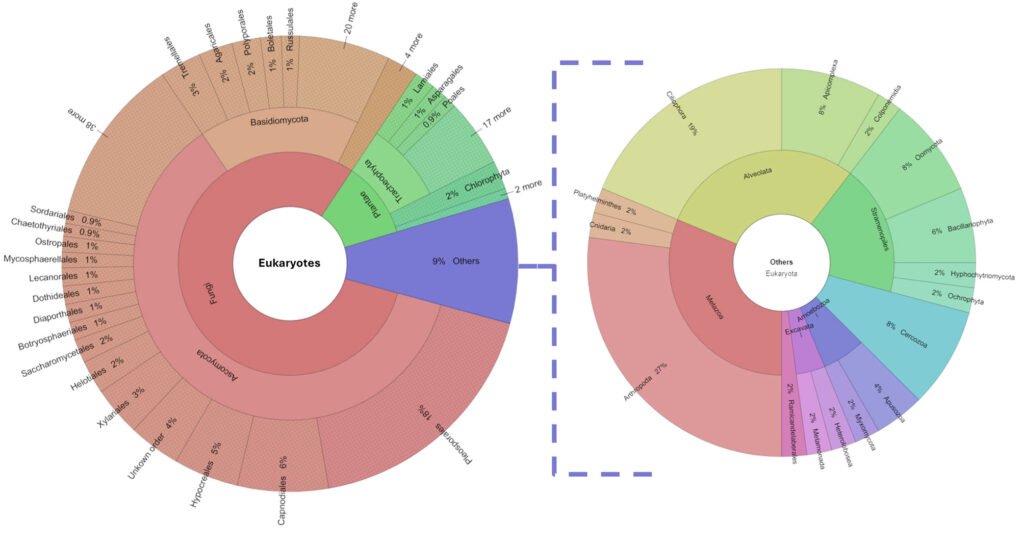

The diversity of organisms living in the tank consisted of 26 phyla and 543 genera. See Supplementary material T1 for a list of assigned taxa. Fungi were dominant, as 80% of the genera belonged to Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, Blastocladiomycota Chytridiomycota, Glomeromycota, Mucoromycota, and Zoopagomycota phyla. The remaining 20% was composed of 19 phyla: Apicomplexa, Apusozoa, Arthropoda, Bacillariophyta, Bryophyta, Cercozoa, Charophyta, Chlorophyta, Ciliophora, Cnidaria, Colponemidia, Heterolobosea, Hyphochytriomycota, Metamonada, Myxomycota, Ochrophyta, Oomycota, Platyhelminthes, and Tracheophyta (Fig. 2). We identified 25 genera of photosynthetic algae from the phyla Bacillariophyta (with the genera Pseudo-nitzschia, Navicula, and Stephanodiscus), Charophyta (Staurastrum), Chlorophyta (Leskea, Didymogenes, Meyerella, Dolichomastix, Bathycoccus, Mychonastes, Trebouxia, Chamaetrichon, Hazenia, Chloroidium, and Pleurastrum), and Ochrophyta (Nannochloropsis). The other photosynthetic organisms were Bryophyta (Fontinalis, Leskea, and Thuidium).

Protists were represented by 44 genera, 4 of which are relevant to human health: Plasmodium (Apicomplexa) which causes paludism, Giardia (Metamonada) which is responsible for giardiasis, Neobalantidium (Cilliophora) that causes balantidiosis, and Spirometra (Plathelmyntes) which is responsible for sparganosis.

Tracheophyta (vascular plants) do not live in the phytotelma but do constitute the debris that accumulates in the bromeliad. They comprised 11% of the identified genera. We found a Sorensen coefficient of 45% similarity among the methods in which 14 taxa at the family level were shared (Supplementary material F1). Arthropoda were represented by 13 genera of the Coleoptera, Diptera, Hymenoptera, Lepidoptera, Odonata, and Pocopodia orders.

Of the eukaryotic organisms, 79% were classified as decomposers, and 7% were classified as micro-predators. In the tank, 3% were photosynthetic organisms, 2% were parasites, and the remaining 9% corresponded to the vascular plants that constitute the detritus. Tracheophyta and Bryophyta constituted the vegetal resources available to micro- and macro-decomposers, and filter feeders. Cercozoa, Apusozoa, Heterolobosea, and Colponemidia were considered micro-predators because they consume some photosynthetic organisms, filter feeders, and micro-decomposers. Ciliophora and 2 Arthropoda genera (Cyprideis and Notodromas) were some of the filter feeders. Apicomplexa, Chytridiomycota, Metamonada, Myxomycota, and Zoopagomycota were the parasites. Aquatic predators were mostly metazoans (Cnidaria and Platyhelminthes) that use filter feeders, photosynthesizers, and macro decomposers as resources. The arthropods Coleoptera, Diptera, Hymenoptera, Lepidoptera, and Odonata were part of the uppermost categories of the trophic network (surface predators). However, their exoskeletons and/or excretions become part of the tank resource or contribute to the nutrient cycling of the microecosystem (Figs. 3, 4).

Figure 2. Percentage of eukaryotic diversity present in the Pseudalcantarea grandis tank.

Discussion

Eukaryotic composition of the Pseudalcantarea grandis community

The abundance of fungi in the Pseudalcantarea tank appeared to correlate with their function in the trophic network. Fungi are the most important degrading group, responsible for organic decomposition and nutrient recycling in forests, aquatic ecosystems, and the phytotelma (Costa & Gusmão, 2015; Grossart et al., 2019; Grothjan et al., 2019). Fungi also have multiple functions in aquatic environment interactions that favor antagonistic and symbiotic members of the community. They can be predators, parasites, or food for heterotrophic protists. Some can use organic matter, pollen, or zooplankton exoskeletons (Zoopagomycota, Chytridiomycota) (Grossart et al., 2019). Vegetal matter decomposition enhances detritus quality for detritivores degrading vegetal polysaccharides into monosaccharides through enzymatic reactions which are then easily digested by microorganisms (Krauss et al., 2011). Fungi and protist interactions for vegetal matter transformation are poorly documented. A symbiotic relationship between them is unknown and difficult to study because of the microscopic scale at which they occur (Grossart et al., 2019).

Figure 3. Graphic representation of Pseudalcantarea grandis tank trophic categories. 1 = Detritus, 2 = micro-decomposers, 3 = macro-decomposers, 4 = photosynthesizers, 5 = filter feeders, 6 = micro-predators, 7 = aquatic predators, 8 = surface predators, and 9 = parasites

Figure 4. Hypothetical trophic level network inside Pseudalcantarea grandis tank. Examples of taxa are listed.

The fungal diversity found in the Pseudalcantarea grandis tank was high compared to that reported in previous studies of other Bromeliaceae species. We found 436 genera, whereas Gomes et al. (2015) identified 36 genera using cultivation techniques. Other papers already pointed out that metagenomic studies detect higher diversity levels than other techniques (Simão et al., 2020). The 36 genera found by Gomes et al. (2015) were also found in P. grandis. Cryptococcus, Candida, and Aureobasidium have specific enzymatic activity in plant material degradation, which suggests that degradation reactions by these organisms are frequent in the phytotelma. The primers used in our study were developed for fungi (White et al., 1990), therefore they might be overrepresented.

We found 44 protist genera in the phytotelma. Some have mixotrophic nutrition, in that they obtain their energy through photo- and heterotrophy depending on the environmental conditions in which they grow (Jones, 2000). In aquatic environments where light is available but dissolved organic carbon (DOC) is scarce, photosynthetic organisms are better represented. Low light and high DOC favor heterotrophic organisms (Jones, 2000). The latter condition is what was present in the sampled tanks. Therefore, the development of photosynthetic protists is not favored because of the large and abundant bacterial community that competes for elements such as phosphorus (Brouard et al., 2012; Herrera-García et al., 2022). In the rainy season, the tank of P. grandis is surrounded by vegetation that intercepts light and deposits leaf litter, therefore favoring the conditions for fungi and decomposers (Grossart et al., 2019; Herrera-García et al., 2022, Kitching, 2000).

Direct observations and sampling of the phytotelma of tropical zones have revealed Diptera, Odonata, Oligochaeta, Ostracoda, beetles, copepods, pseudoscorpions, scorpions, isopods, Lepidoptera, hemipterans, homopterans, orthopterans, and arachnids in tank bromeliads (Cutz-Pool et al., 2016; Marino et al., 2013). Using environmental DNA with specific primers, amphibians (Brozio et al., 2017) and ciliates (Simão et al., 2017) have been found in tank bromeliads with high water availability. These results suggest that aridity and strong water seasonality in our study area were responsible for the lack of amphibians and the low arthropod and ciliate diversity we found.

Phytotelma seasonality is an important factor. In a rainy forest, the annual precipitation is 3,000 mm and rain is present for 280 days, therefore the water in the tank lasts longer (Brouard et al., 2012). In contrast, in our location, the annual precipitation is 391 mm and the phytotelma is available only through the rainy season from May to June (INFAED, 2012). The presence of Plasmodium is relevant since its most common vector is Aedes, suggesting that at some point during the phytotelma duration, the mosquito is in contact with the water, completing the parasite life cycle (Williams, 2007).

The absence of vertebrates is characteristic of phytotelma communities (Mogi, 2004). One exception is in rainforest bromeliad, where bromeliad tadpoles can be found. We did not find vertebrates. Strong seasonality was probably the reason for their absence. Not all OTUs could be assigned to the species or genus taxonomic category at 99% identity level we used. We did not find an identity for 762 of the 23,984 sequences, possibly because the sequences of these organisms are not available in the NCBI database, or because the organisms have not yet been described.

The tracheophytes found in the phytotelma could not be identified at the generic level. There are 2 possible explanations: the reads were short (150 bp) and therefore insufficient, or the genera growing at the canyon are not in the GenBank NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information) database. However, 30 families of vascular plants were detected, 16 of which correspond to the families found by field collection.

Trophic structure of the Pseudalcantarea grandis tank

We propose 9 trophic levels for tank bromeliads in arid zones, —2 more than those suggested by Mogi (2004), and 3 more than those suggested by Brouard et al. (2012). Detritus is the main nutrient source. Macrodecomposers process leaf litter into small organic matter particles, including their waste. The particles are then stored in the phytotelma where filterers and invertebrates process them. Dead organisms, feces, and leaf litter stored at the bottom of the tank are used by bacteria and other microorganisms such as fungi to assimilate nutrients (Brouard et al., 2012). We found that 48 plant genera (45 Tracheophyta, and 3 Bryophyta) constitute the detritus, and although Brouard et al. (2012) recognized organic litter as a resource, they did not identify the organisms that provided it. The large amount of detritus was due to the type of surrounding vegetation, which was a tropical deciduous forest in this study. In P. grandis macro decomposers are fungi of the Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, and Myxomycota phyla. We concur with Brouard et al. (2012) that ciliates are filterers. Mogi (2004) did not consider microorganisms to be autotrophs, but Brouard et al. (2012) included that category, and in P. grandis algae constitute this level. Insects were categorized as surface predators in their diagram; they include the odonate family Coenagrionidae, which includes the 2 genera we found in P. grandis, Ischnura, and Agriocnemis (Brouard et al., 2012). Neither Mogi (2004) nor Brouard et al. (2012) included parasites at a trophic level, but some of the genera found in P. grandis are obligate parasites, mostly from the Alveolata kingdom, which has birds and mammals as hosts but uses arthropods as vectors.

We found 26 phyla with 543 genera in the phytotelma of P. grandis growing in an arid zone. The identified diversity suggested that the organisms that inhabit these small ephemeral water bodies are adapted to prolonged dry spells and develop quickly when the phytotelma has water. The biota was mostly composed of fungi (over 80% of the diversity) that specialize in plant detritus degradation. Water bodies shelter aquatic groups that cannot exist in areas outside the P. grandis phytotelma. It is easier to assess the diversity of organisms within a tank than to comprehend their interactions. The trophic network proposed for eukaryotes indicates that they fulfill different functions.

As final considerations, we conclude that the analyzed phytotelma had a large detritus accumulation, and water was present briefly. Most of the diversity belonged to fungi (80%) because of the large amount of plant detritus in the tank. Photosynthesizers were scarce but included 25 algal genera and 3 Bryophyta. We found 45% Sorensen coefficient similarity between the plant detritus and the specimens collected with herbarium specimens. We also found a low arthropod and ciliate diversity, and the tank also harbors protist genera, some of which have medical implications. We found 9 trophic levels in the tank. Unlike tropical areas, in which algal production can support non-detrital food webs, in our arid zone system, detritus degradation was the main energy source.

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by Conahcyt through grant 293833 for the Laboratorio Nacional de Identificación y Caracterización Vegetal. Diana Velázquez designed and executed Figure 3. Two anonymous reviewers helped to improve the manuscript with their comments.

References

Altschul, S. F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E. W., & Lipman, D. J. (1990). Basic local alignment search tool. Journal of Molecular Biology, 215, 403–410. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2

Benzing, D. H., & Renfrow, A. (1974). The mineral nutrition of Bromeliaceae. Botanical Gazette, 135, 281–288. https://doi.org/10.1086/336762

Benzing, D. H. (2000). Bromeliaceae: profile of an adaptive radiation. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

Bernal, R., Valverde, T., & Hernández-Rosas, L. (2006). Habitat preference of the epiphyte Tillandsia recurvata (Bromeliaceae) in a semi-desert environment in Central Mexico. Canadian Journal of Botany, 83, 1238–1247. https://doi.org/10.1139/b05-076

Brandt, F. B., Martinson, G. O., & Conrad, R. (2017). Bromeliad tanks are unique habitats for microbial communities involved in methane turnover. Plant and Soil, 410, 167–179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-016-2988-9

Brouard, O., Céréghino, R., Corbara, B., Leroy, C., Pelozuelo, L., Dejean, A. et al. (2012). Understorey environments influence functional diversity in tank-bromeliad ecosystems. Freshwater Biology, 57, 815–823. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2427.2012.02749.x

Brozio, S., Manson, C., Gourevitch, E., Burns, T. J., Greener, M. S., Downie, J. R. et al. (2017). Development and application of an eDNA method to detect the critically endangered Trinidad golden tree frog (Phytotriades auratus) in bromeliad phytotelmata. Plos One, 12, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0170619

Costa, L. A., & Gusmão, L. F. P. (2015). Characterization saprobic fungi on leaf litter of two species of trees in the Atlantic Forest, Brazil. Brazilian Journal of Microbiology, 46, 1027–1035. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1517-838246420140548

Cutz-Pool, L. Q., Ramírez-Vázquez, U. Y, Castro-Pérez, J. M, Puc-Paz, W. A., & Ortiz-León, H. J. (2016). La artropo-

dofauna asociada a Tillandsia fasciculata en bajos inundados de tres sitios de Quintana Roo, México. Entomología Mexicana, 3, 576–581.

Espejo-Serna, A., & López-Ferrari, A. R. (2018). La familia Bromeliaceae en México. Botanical Sciences, 96, 533–554. https://doi.org/10.17129/botsci.1918

Espejo-Serna, A., López-Ferrari, A., & Ramírez-Murillo, I. (2010). Bromeliaceae. Flora del Bajío y Regiones Adyacentes, 165, 1–82.

Goffredi, S. K., Kantor, A. H., & Woodside, W. T. (2011). Aquatic Microbial Habitats Within a Neotropical Rain-

forest: Bromeliads and pH-Associated Trends in Bacterial Diversity and Composition. Microbial Ecology, 61, 529–542. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-010-9781-8

Gomes, F. C. O., Safar, S. V. B., Marques, A. R., Medeiros, A. O., Santos, A. R. O., Carvalho, C. et al. (2015). The diversity and extracellular enzymatic activities of yeasts isolated from water tanks of Vriesea minarum, an endangered bromeliad species in Brazil, and the description of Occultifur brasiliensis f.a., sp. nov. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, International Journal of General and Molecular Microbiology, 107, 597–611. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10482-014-0356-4

Gouda, E. J., Butcher, D., & Dijkgraaf, L. (2024) Encyclopaedia of Bromeliads, Version 5. Utrecht University Botanic Gardens, online (accessed: 02-10-2024): http://bromeliad.nl/encyclopedia/

Grossart, H. P., Van den Wyngaert, S., Kagami, M., Wurzbacher, C., Cunliffe, M., & Rojas-Jimenez, K. (2019). Fungi in aquatic ecosystems. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 17, 339–354. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-019-0175-8

Grothjan, J. J., & Young, E. B. (2019). Diverse microbial communities hosted by the model carnivorous pitcher plant Sarracenia purpurea: Analysis of both bacterial and eukaryotic composition across distinct host plant populations. PeerJ, 2019, e6392. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.6392

Hernández, H. M., & Bárcenas, R. T. (1995). Endangered Cacti in the Chihuahuan Desert: I. Distribution Patterns. Conservation Biology, 9, 1176–1188. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1739.1995.9051169.x-i1

Hernández, H. M., & Gómez-Hinostrosa, C. (2005). Cactus diversity and endemism in the Chihuahuan Desert Region. EnJ. L. Cartron, G. Ceballos, & R. Felger (Eds.), Biodiversity, ecosystems and conservation in Northern Mexico (pp264–275). New York: Oxford University Press.

Hernández-Magaña, R., Hernández-Oria, J. G., & Chávez, R. (2017). Datos para la conservación florística en función de la amplitud geográfica de las especies en el Semidesierto Queretano, México. Acta Botanica Mexicana, 140, 105. https://doi.org/10.21829/abm99.2012.22

Herrera-García, J. A., Martínez, M., Zamora-Tavares, P., Vargas-Ponce, O., Hernández-Sandoval, L., & Rodríguez-Zaragoza, F. A. (2022). Metabarcoding of the phytotelmata of Pseudalcantarea grandis (Bromeliaceae) from an arid zone. PeerJ, 10, e12706. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.12706

Huson, D. H., Beier, S., Flade, I., Górska, A., El-Hadidi, M., Mitra, S. et al. (2016). MEGAN Community Edition – Interactive Exploration and Analysis of Large-Scale Microbiome Sequencing Data. Plos Computational Biology, 12, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004957

INAFED (Instituto Nacional para el Federalismo y el Desarrollo Municipal). (2012). Zimapán. Enciclopedia de los municipios y Delegaciones de México. http://www.inafed.gob.mx/work/enciclopedia/EMM13hidalgo/municipios/13084a.html

Jones, R. I. (2000). Mixotrophy in planktonic protists: an overview. Freshwater Biology, 45, 219–226. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2427.2000.00672.x

Kitching, R. (2000). Food webs and container habitats: the natural history and ecology of phytotelma. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511542107

Kitching, R. L. (2001). Food webs in phytotelmata: “Bottom-Up” and “Top- Down’” Explanations for Community Structure. Annual Review of Entomology, 46, 729–760. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ento.51.110104.151120

Krauss, G. J., Solé, M., Krauss, G., Schlosser, D., Wesenberg, D., & Bärlocher, F. (2011). Fungi in freshwaters: Ecology, physiology and biochemical potential. FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 35, 620–651. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6976.20

11.00266.x

Louca, S., Jacques, S. M. S., Pires, A. P. F., Leal, J. S., González, A. L., Doebeli, M. et al. (2017). Functional structure of the bromeliad tank microbiome is strongly shaped by local geochemical conditions. Environmental Microbiology, 19, 3132–3151. https://doi.org/10.1111/1462-2920.13788

Marino, N. A. C., Srivastava, D. S., & Farjalla, V. F. (2013). Aquatic macroinvertebrate community composition in tank-bromeliads is determined by bromeliad species and its constrained characteristics. Insect Conservation and Diversity, 6, 372–380. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-4598.2012.00224.x

Mogi, M. (2004). Phytotelmata: hidden freshwater habitats supporting unique faunas. In C. M. Yule, & H. S. Yong (Eds.), Freshwater invertebrates of the Malaysian region (pp. 13–22). Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Academy of Sciences Malaysia.

Ngai, J. T., & Srivastava, D. S. (2006). Predators accelerate nutrient cycling in a bromeliad ecosystem. Science, 314, 963. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1132598

Nievola, C. C., Mercier, H., & Majerowicz, N. (2001). Levels of Nitrogen assimilation in bromeliads. Journal of Plant Nutrition, 24, 1387–1398. https://doi.org/10.1081/PLN-100106989

Ramírez-Murillo, I., Carnevali-Fernández, G., & Chi-May, F. (2004). Guía ilustrada de las Bromeliaceae de la porción mexicana de la península de Yucatán. Yucatán: Centro de Investigación Científica de Yucatán.

Ramos, G. J. P., & do Nascimento Moura, C. W. (2019). Algae and cyanobacteria in phytotelmata: diversity, ecological aspects, and conservation. Biodiversity and Conservation, 28, 1667–1697. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-019-01771-2

Rodríguez-Núñez, K. M., Rullan-Cardec, J. M., & Ríos-Velázquez, C. (2018). The metagenome of bromeliads phytotelma in Puerto Rico. Data in Brief, 16, 19–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2017.10.065

Rojas, S., Castillejos-Cruz, C., & Solano, E. (2013). Florística y relaciones fitogeográficas del matorral xerófilo en el valle de Tecozautla, Hidalgo, México. Botanical Sciences, 91, 273–294. https://doi.org/10.17129/botsci.8

Rzedowski, J. (2006). Vegetación de México. México D.F.: Conabio.

Simão, T. L. L., Borges, A. G., Gano, K. A., Davis-Richardson, A. G., Brown, C. T., Fagen, J. R. et al. (2017). Characterization of ciliate diversity in bromeliad tank waters from the Brazilian Atlantic Forest. European Journal of Protistology, 61, 359–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejop.2017.05.005

Simão, T. L. L., Utz, L. R. P., Dias, R., Giongo, A., Triplett, E. W., & Eizirik, E. (2020). Remarkably complex microbial community composition in bromeliad tank waters revealed by eDNA metabarcoding. Journal of Eucaryotic Microbiology, 67, 593–607. https://doi.org/10.1111/jeu.12814

Simpson, M. G. (2006). Plant systematics. Amsterdam: Elsevier/Academic Press.

Takahashi, C. A., & Mercier, H. (2011). Nitrogen metabolism in leaves of a tank epiphytic bromeliad: characterization of a spatial and functional division. Journal of Plant Physiology, 168, 1208–1216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jplph.2011.01.008

Tree of Life Web Project, (2019). Tree of life. Website. http://tolweb.org/tree/

White, T. J., Bruns, T., Lee, S., & Taylor, J. (1990). Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for Phylogenetics. In M. A. Innis, D. H. Gelfand, J. J. Sninsky, T. J. White (Eds.), PCR Protocols (January) (pp. 315–322). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-372180-8.50042-1

Williams, D. D. (2007). Other temporary water habitats. The Biology of temporary waters. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198528128.001.0001