Oscar Iván González-Romero a, Xochitl G. Vital a, b, *

a Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Facultad de Ciencias, Circuito Exterior s/n, Ciudad Universitaria, Coyoacán, 04510 Ciudad de México, México

b Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Posgrado en Ciencias Biológicas, Facultad de Ciencias, Circuito Exterior s/n, Ciudad Universitaria, Coyoacán, 04510 Ciudad de México, México

*Corresponding autor: vital@ciencias.unam.mx (X.G. Vital)

Received: 18 August 2024; accepted: 5 February 2025

Abstract

While the diversity of sea slugs in the northern area of the Pacific coast of Mexico has been studied thoroughly in the last decades, little is known about the composition of species in the southern states of Mexico. Several field trips were made in 5 localities of Bahías de Huatulco, Oaxaca, where specialized sampling methods focused on sea slugs were carried out. Herein, we documented 49 species of sea slugs, including 37 new records for the state, which increases to 58 species the total sea slug richness known for Oaxaca. This study updates the inventory of sea slugs for the Mexican Pacific coast and contributes to the knowledge of the marine fauna of the Natural Protected Area “Parque Nacional Huatulco”.

Keywords: Bahías de Huatulco; Coral reefs; Molluscs; Nudibranchia; Tropical Eastern Pacific

Babosas marinas (Gastropoda: Heterobranchia) de Huatulco: nuevos registros y ampliaciones de distribución para Oaxaca, México

Resumen

Mientras que la diversidad de babosas marinas en la zona norte de la costa del Pacífico mexicano ha sido estudiada de forma exhaustiva en las últimas décadas, poco se sabe acerca de la composición de especies en los estados del sur de México. Se realizaron diversas visitas a 5 localidades de las bahías de Huatulco, Oaxaca, donde se llevaron a cabo métodos de muestreo especializados con enfoque en babosas marinas. Aquí censamos 49 especies de babosas marinas, con 37 nuevos registros para el estado, lo que incrementa la riqueza de babosas marinas conocida para Oaxaca a 58 especies. Este estudio actualiza el inventario de babosas marinas para la costa del Pacífico mexicano y contribuye al conocimiento de la fauna marina del Área Natural Protegida “Parque Nacional Huatulco”.

Palabras clave: Bahías de Huatulco; Arrecifes de coral; Moluscos; Nudibranchia; Pacífico este tropical

Introduction

Heterobranch sea slugs are gastropods with more than 8,400 described species distributed in all the oceans of the planet, from the intertidal zone to deep waters (Behrens et al., 2022; Camacho-García et al., 2005). Some of these molluscs can do some of the most exceptional processes in the metazoans, such as the incorporation of functional chloroplasts or nematocysts into their tissues (Goodheart & Bely, 2017; Händeler et al., 2009). Furthermore, sea slugs can be important model organisms in several study areas from neuroscience to global climate change (Kandel, 1979; Ziegler et al., 2014); a source of biomedical compounds used for creating novel drugs (Dean & Prinsep, 2017; Fisch et al., 2017) and an attractive target to professional and amateur underwater photographers worldwide (Behrens, 2005).

More than 370 species of sea slugs have been recorded in the Eastern Pacific from Alaska to Central America (Behrens et al., 2022), of which around 234 have been found on the Mexican Pacific coast (Hermosillo et al., 2006). Although several studies on sea slugs have been performed in this region (e.g., Angulo-Campillo, 2005; Bertsch, 2014; Flores-Rodríguez et al., 2017; Hermosillo, 2009, 2011; Hermosillo & Behrens, 2005; Hermosillo & Gosliner, 2008; Verdín-Padilla et al., 2010), most of them are focused on the northern coast of Mexico, whereas the composition of species of the southern coast, corresponding to the states of Oaxaca and Chiapas, has been poorly recorded in faunal inventories. The current knowledge of Oaxaca’s sea slug fauna comes from 2 checklists of intertidal molluscs on rocky shores of the state (Holguín-Quiñones & González-Pedraza, 1989; Rodríguez-Palacios et al., 1988), a review of the sea slugs preserved at Colección Nacional de Moluscos (CNMO) from Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM) (Zamora-Silva & Naranjo-García, 2008), and an ecological analysis of the richness and abundance of molluscs associated with coral ecosystems in the Tropical Eastern Pacific (Barrientos-Luján et al., 2021). Altogether, these studies sum up to 10 known species of Heterobranch sea slugs on the coastal shore of Oaxaca.

Biological inventories are a fundamental base that provides essential information for conservation strategies, such as establishing natural protected areas or monitoring their condition inside them (Alexander et al., 2009; Schejter et al., 2016). Marine molluscs are useful in rapid biodiversity assessments (Benkendorff & Davis, 2002), and they could serve as indicators of the total biological richness in marine reserves (Gladstone, 2002), which possibly extrapolates to different areas and types of habitats. Sea slugs are one of the most diverse groups within the marine molluscs. Nonetheless, they are apparently “rare in space and time” (Schubert & Smith, 2020), as they are not always recorded in the biological inventories due to their small size, their camouflage strategies and inadequate collecting methods applied on the field. This work aims to provide information on the diversity of sea slugs in the southern region of the Mexican Pacific coast, based on surveys conducted in different coral communities in Oaxaca.

Materials and methods

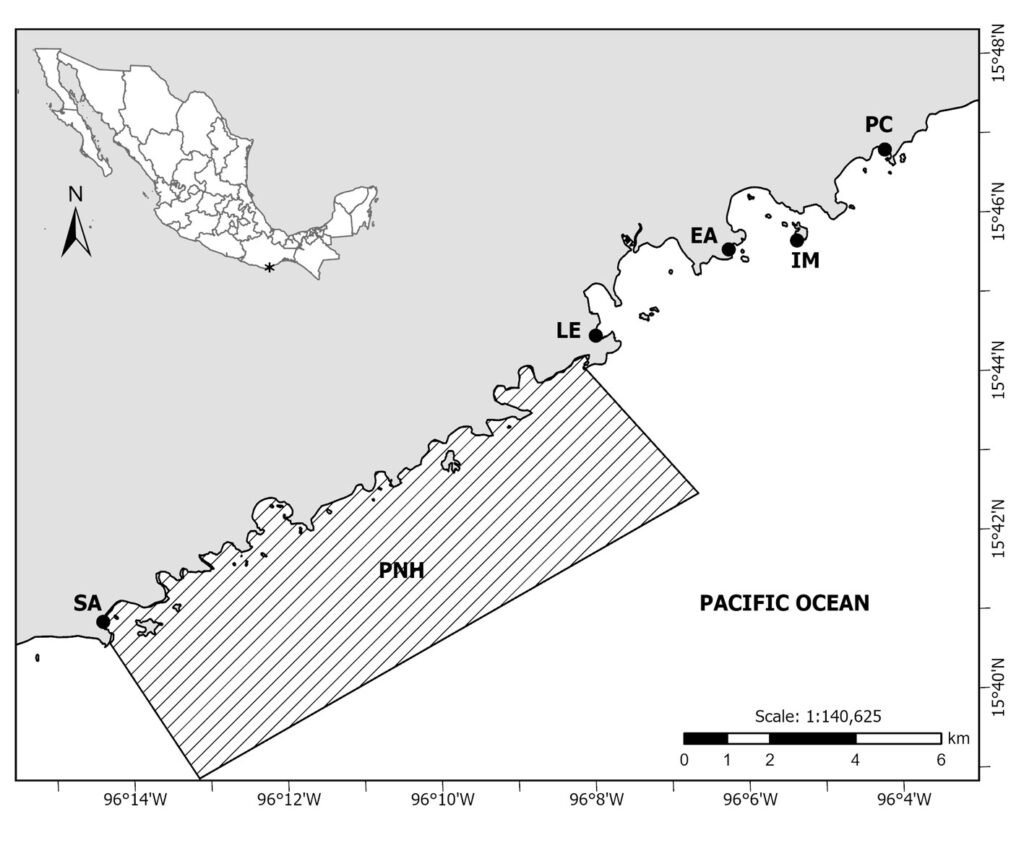

Five localities of the bay complex known as Bahías de Huatulco, Oaxaca were selected for field studies: San Agustín (hereafter Agustín), La Entrega (hereafter Entrega), El Arrocito (hereafter Arrocito), Isla Montosa (hereafter Montosa) and Playa Conejos (hereafter Conejos). Agustín is located within the Natural Protected Area in the category of National Park “Parque Nacional Huatulco (PNH)” (Conanp, 2003) (Fig. 1, Table 1). This locality has a large and compact homogenous platform of coral colonies dominated by Pocillopora damicornis with patches of dead corals and rocks, similar to Entrega, which additionally has shallow zones of algal turf (López-Pérez & Hernández-Ballesteros, 2004; Ramírez-González, 2005). Arrocito’s substrate is composed of rocks overgrown by algal turf and dead coral fragments mostly in shallow environments, with few coralline formations and a high abundance of sponges. Conejos has big rocks with a sandy bottom and low presence of corals at shallow depths (Ramírez-González, 2005). Finally, Montosa is an island with mixed patches of corals, sand and large boulders as a dominant substrate (López-Pérez & Hernández-Ballesteros, 2004).

A total of 17 field trips were conducted between May 2017 and March 2018, 4 at each locality (except on Montosa, where we searched only once). Using snorkelling and SCUBA diving at maximum depths of 18 m, searches were conducted in subtidal environments on different substrates (Table 1). Most of the specimens were collected in all localities, when necessary, except in Agustín where photos, identification and measuring of the organisms were taken in situ. Additionally, different algal morphotypes where sea slugs may potentially be found were collected in all localities, excluding Agustín. The algae collected were placed in trays with low seawater level, then they were examined after 2 to 3 hours to find specimens attached to the tray walls (Urbano et al., 2019). All organisms were measured and photographed while they were alive and identified according to sea slug identification guides for the Pacific east coast (Behrens et al., 2022; Camacho-García et al., 2005; Hermosillo et al., 2006). Afterwards, the collected specimens were narcotized with magnesium chloride (MgCl2), preserved with ethanol (96º) (Urbano et al., 2019) and deposited in Colección Nacional de Moluscos (CNMO), Instituto de Biología, UNAM. The nomenclature used in this work follows Bouchet et al. (2017) for supra-family and family categories and World Register of Marine Species (Horton et al., 2024) for genus and species categories. We present the new records for Oaxaca: number of organisms found per locality, their size, their collection number, distribution in the Pacific east coast and remarks of the species, as well as a brief description of undetermined species.

Figure 1. Localities in Bahías de Huatulco (black dots) where this study was held. San Agustín (SA); La Entrega (LE); El Arrocito (EA); Isla Montosa (IM); Playa Conejos (PC). The area belonging to the marine part of the Parque Nacional Huatulco (PNH) is shown in the hatched polygon. Map by O.I. González-Romero.

Table 1

Collecting sites in Bahías de Huatulco: San Agustín, La Entrega, El Arrocito, Isla Montosa, Playa Conejos. Sampling technique: snorkelling (S), scuba diving (SD).

| Locality | Latitude (N) | Longitude (W) | Sampling technique | Substrate composition |

| San Agustín | 15°41.185’ | 96°14.254’ | S | Compact coral colonies, rocks and dead coral patches |

| La Entrega | 15°44.642’ | 96°07.732’ | S, SD | Compact coral colonies, rocks, algae and dead coral patches |

| El Arrocito | 15°45.672’ | 96°06.008’ | S, SD | Rocks with algal turf, coral, sponges and dead coral patches |

| Isla Montosa | 15°45.725’ | 96°05.120’ | SD | Boulders, sand and corals |

| Playa Conejos | 15°46.722’ | 96°03.853’ | S | Boulders, sand and corals |

Results

A total of 298 specimens belonging to 49 species (38 determined to species level, 10 to genus and 1 to family) were recorded from 5 localities in Bahías de Huatulco; the species were distributed in 22 families and 6 orders/superorders. Nudibranchia had the highest number of species (27), followed by Sacoglossa (10), Aplysiida (6), Pleurobranchida (3), and Cephalaspidea (2), while Umbraculida was represented only by 1 species. A list of the sea slugs recorded from Bahías de Huatulco in this study, complemented with the previous records from Oaxaca, is given in Table 2.

Class Gastropoda Cuvier, 1795

Subclass Heterobranchia Gray, 1840

Infraclass Euthyneura Spengel, 1881

Cohort Ringipleura Kano, Brenzinger, Nützel, Wilson and Schrödl, 2016

Subcohort Nudipleura Wägele and Willan, 2000

Order Pleurobranchida Pelseneer, 1906

Family Pleurobranchidae Gray, 1827

Berthellina ilisima Ev. Marcus and Er. Marcus, 1967

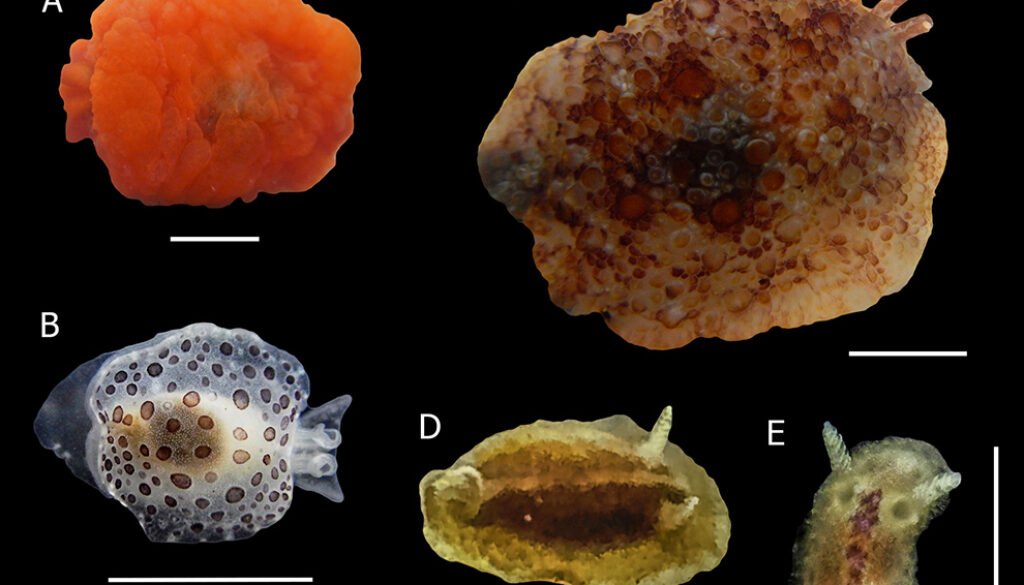

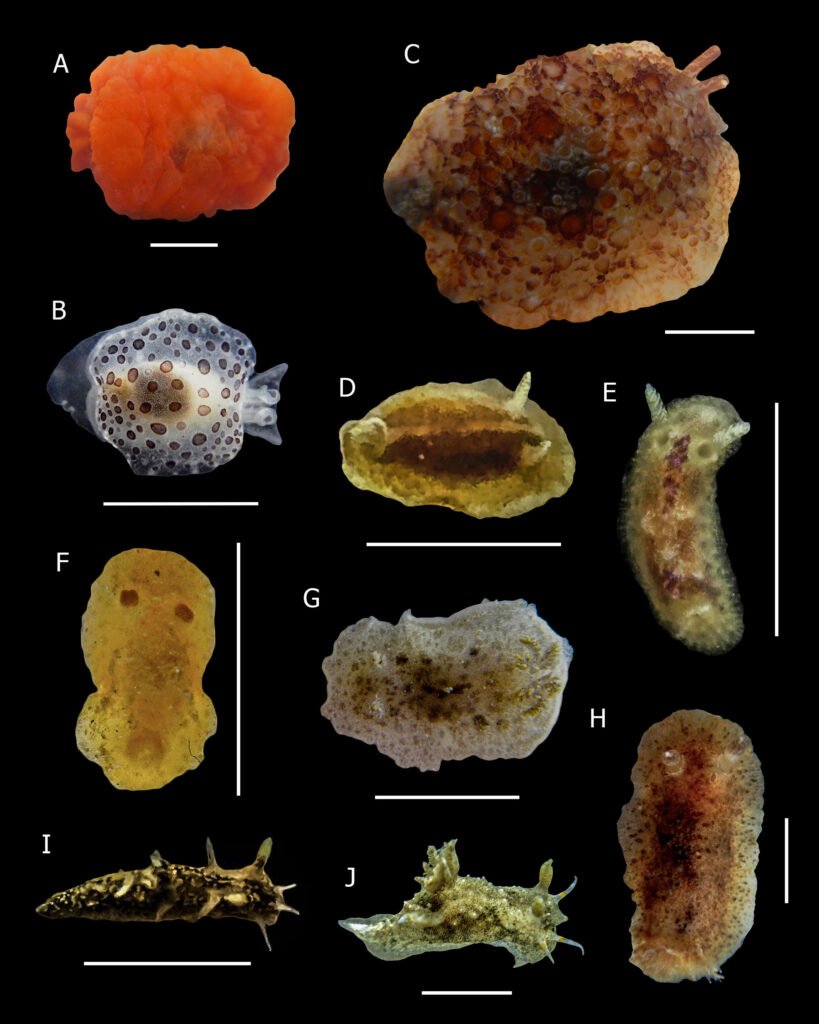

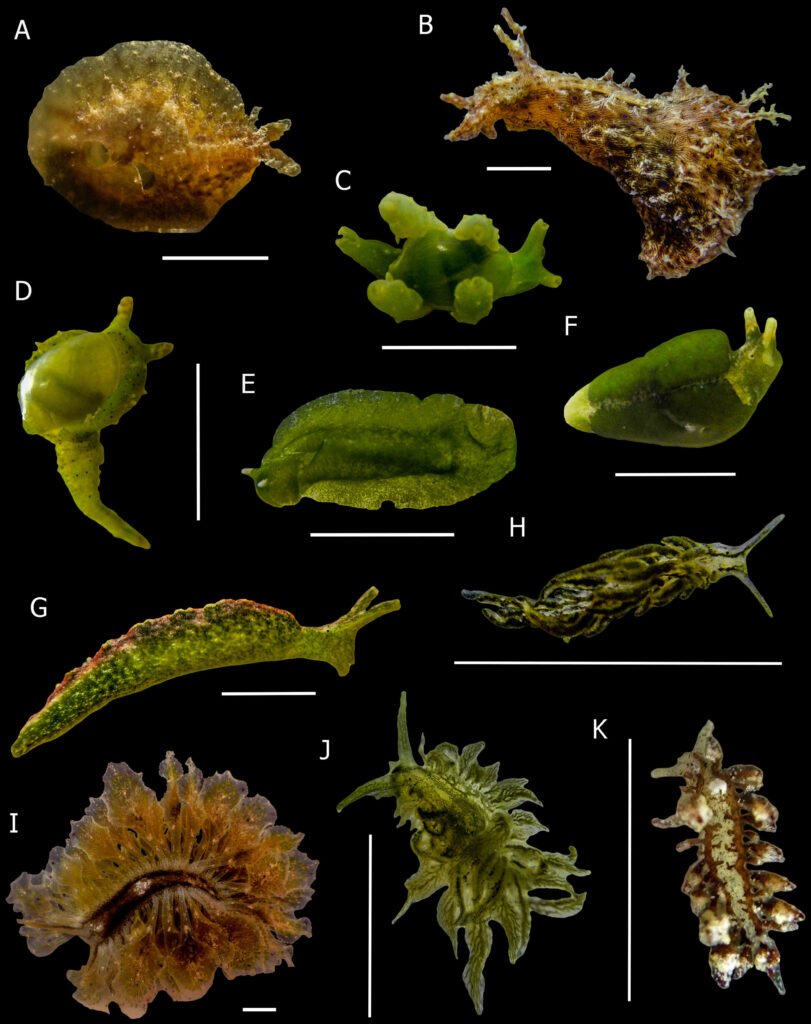

(Fig. 2A)

Material examined: 1 organism (18 mm), Entrega (CNMO8025).

Distribution: from Santa Barbara, California to Islas Galapagos, Ecuador (Behrens et al., 2022).

Remarks: animals with nocturnal habits and spongivorous diet (Valdés, 2019).

Berthella sp.

(Fig. 2B)

Material examined: 2 organisms (5, 8 mm), Arrocito (CNMO8274).

Distribution: El Arrocito, Bahías de Huatulco, Oaxaca (this study).

Diagnosis: translucent whitish body with numerous small opaque white dots and low rounded brown tubercles on the dorsum. Small translucent internal shell. The foot protrudes posteriorly from the mantle. The oral velum is triangular and the rolled rhinophores are partially fused.

Remarks: organisms were found under rocks near white sponges. The observed characters in the specimens allowed their identification only to the genus level. Berthella andromeda, B. strongi and B. martensi are also distributed in the Pacific east coast; however, our specimens had a more translucent and white body than B. strongi and they did not present the opaque white transverse bar of B. andromeda (Ghanimi et al., 2020); the dots on the notum also were darker and more regular compared with B. martensi, which has a band along the edge of the mantle (Behrens et al., 2022).

Pleurobranchus digueti Rochebrune, 1895

(Fig. 2C)

Material examined: 3 organisms (15-20 mm), Entrega (CNMO8020); 1 organism (35 mm), Arrocito (CNMO8006); 1 organism (10 mm), Montosa (CNMO7965).

Distribution: from Santa Barbara, California to Islas Galapagos, Ecuador (Behrens et al., 2022).

Remarks: nocturnal animals hide under rocks during the day (Valdés, 2019).

Order Nudibranchia Cuvier, 1817

Family Dorididae Rafinesque, 1815

Dorididae sp.

(Fig. 2D)

Material examined: 1 organism (6 mm), Conejos (CNMO8261).

Distribution: Playa Conejos, Bahías de Huatulco, Oaxaca (this study).

Diagnosis: yellowish body, with an oval orange-brownish patch covering the dorsum and divided by a cream-whitish band that runs through the middle of the rhinophores all the way to the branchial area. The lamellated rhinophores and the gills are the same colour as the body.

Remarks: the specimen was found under rocks at approximately 3 m depth. The observed characters in the organism did not resemble any recorded species in the literature, but they allowed its identification up to the family level.

Doris sp.(Risbec, 1928)

(Fig. 2E)

Material examined: 1 organism (6 mm), Conejos (CNMO8260).

Distribution: Playa Conejos, Bahías de Huatulco, Oaxaca (this study).

Diagnosis: pale yellowish body with discontinued purple band between the rhinophores and the posterior area of the body. The animal had big tubercles in the central area of the dorsum with visible translucent spicules. Rhinophores were lamellated.

Remarks: specimen found on algae of the genus Caulerpa. This specimen resembles the organism illustrated in Behrens et al. (2022) as Doris immonda; however, the previous authors mention that this identification might not be valid due to its geographical distribution, as D. immonda was originally described for the Indo-Pacific. Also, the diagnosis of D. immonda in Gosliner et al. (2018) does not mention the purple band observed in this individual, these authors described a white opaque marking across the body instead. Therefore, we decided to include this species as Doris sp. until a further review of this taxon is made.

Family Discodorididae Bergh, 1891

Diaulula nayarita (Ortea & Llera, 1981)

(Fig. 2F)

Material examined: 1 organism (4 mm), Arrocito (CNMO7974).

Distribution: from Punta Eugenia, Baja California to Panama (Camacho-García et al., 2005).

Remarks: found under rocks near sponges of the same colour as the specimen.

Discodoris ketos (Marcus & Marcus, 1967)

(Fig. 2G)

Material examined: 1 organism (8 mm), Arrocito (CNMO8028).

Distribution: Gulf of California. Mexico to Islas Galapagos, Ecuador (Behrens et al., 2022).

Remarks: it is still unclear whether this species is the same as the circumtropical species Tayuva lilacina (Behrens et al., 2022). Discodoris ketos has a highly specialised diet, feeding on the sponge Haliclona caerulea (Verdín-Padilla et al., 2010).

Geitodoris mavis (Marcus & Marcus, 1967)

(Fig. 2H)

Material examined: 1 organism (15 mm), Entrega (CNMO7964). 1 organism (13 mm), Arrocito (CNMO8029).

Distribution: from Rosarito, Baja California to Islas Galapagos, Ecuador (Behrens et al., 2022).

Remarks: live specimens darkened their gills when disturbed.

Family Polyceridae Alder and Hancock, 1845

Polycera anae Pola et al., 2014

(Fig. 2I)

Material examined: 2 organisms (8, 10 mm), Conejos (CNMO7981).

Distribution: from Mexico to Costa Rica (Pola et al., 2014).

Remarks: found on algae of the genus Padina. Specimens found in this work exceed the maximum length of 5 mm reported for the species by Pola et al. (2014).

Polycera cf. hedgpethi Er. Marcus, 1964

(Fig. 2J)

Table 2

Sea slug fauna recorded from Oaxaca state based on this study and the literature. Localities: Puerto Ángel (PA), San Agustín (SA), El Maguey (EM), La Entrega (LE), El Arrocito (EA), Isla Montosa (IM), Playa Conejos (PC), Santa Cruz (SC), Not available data (ND). New records for the state (*). Only determined species in literature were included. References: 1Holguín-Quiñones and González-Pedraza (1989); 2Rodríguez-Palacios et al. (1988); 3Zamora-Silva and Naranjo-García (2008); 4Barrientos-Luján et al. (2021); 5This study.

| Family | Species | PA | SA | EM | LE | EA | IM | PC | SC | ND | Reference |

| Pleurobranchidae | Berthellina ilisima* | • | 5 | ||||||||

| Berthella sp. | • | 5 | |||||||||

| Pleurobranchus digueti* | • | • | • | 5 | |||||||

| Dorididae | Dorididae sp. | • | 5 | ||||||||

| Doris sp. | • | 5 | |||||||||

| Discodorididae | Diaulula nayarita* | • | 5 | ||||||||

| Diaulula sandiegensis | • | 2 | |||||||||

| Discodoris ketos* | • | 5 | |||||||||

| Geitodoris mavis* | • | • | 5 | ||||||||

| Polyceridae | Polycera anae* | • | 5 | ||||||||

| Polycera cf. hedgpethi* | • | 5 | |||||||||

| Tambja abdere* | • | 5 | |||||||||

| Chromodorididae | Felimida sphoni* | • | • | • | 5 | ||||||

| Chromolaichma dalli* | • | • | • | 5 | |||||||

| Chromolaichma sedna* | • | • | 5 | ||||||||

| Felimare agassizii* | • | • | • | • | 5 | ||||||

| Cadlinidae | Cadlina sp. | • | • | • | 5 | ||||||

| Dendrodorididae | Dendrodoris krebsii | • | 2 | ||||||||

| Doriopsilla janaina* | • | • | • | 5 | |||||||

| Tritoniidae | Tritonia festiva | • | 2 | ||||||||

| Hancockiidae | Hancockia californica* | • | 5 | ||||||||

| Flabellinidae | Coryphellina marcusorum* | • | 5 | ||||||||

| Samla telja* | • | • | • | • | 5 | ||||||

| Cuthonidae | Cuthona divae | • | 2 | ||||||||

| Cuthona sp. 1 | • | 5 | |||||||||

| Cuthona sp. 2 | • | 5 | |||||||||

| Aeolidiidae | Bulbaeolidia sulphurea* | • | 5 | ||||||||

| Anteaeolidiella chromosoma* | • | • | 5 | ||||||||

| Anteaeolidiella ireneae* | • | 5 | |||||||||

| Baeolidia moebii* | • | 5 | |||||||||

| Limenandra confusa* | • | • | 5 | ||||||||

| Spurilla braziliana* | • | 5 | |||||||||

| Facelinidae | Favorinus elenalexiarum* | • | • | 5 | |||||||

| Phidiana lascrucensis* | • | • | • | • | • | 5 | |||||

| Tylodinidae | Tylodina fungina* | • | 5 | ||||||||

| Table 2. Continued | |||||||||||

| Bullidae | Bulla punctulata | • | 1 | ||||||||

| Bulla gouldiana | • | 4 | |||||||||

| Haminoeidae | Haminoea sp. | • | • | 5 | |||||||

| Aliculastrum exaratum | • | 4 | |||||||||

| Aglajidae | Navanax aenigmaticus* | • | • | • | 5 | ||||||

| Aplysiidae | Aplysia cf. cedrosensis* | • | 5 | ||||||||

| Aplysia californica | • | 2 | |||||||||

| Aplysia hooveri* | • | • | • | • | 5 | ||||||

| Dolabella cf. auricularia* | • | • | 5 | ||||||||

| Dolabella californica | • | 2 | |||||||||

| Dolabrifera nicaraguana* | • | 5 | |||||||||

| Phyllaplysia padinae* | • | 5 | |||||||||

| Stylocheilus rickettsi* | • | • | 5 | ||||||||

| Oxynoidae | Lobiger cf. souverbii* | • | • | 5 | |||||||

| Oxynoe aliciae* | • | 5 | |||||||||

| Plakobranchidae | Elysia diomedea | • | • | • | • | • | 3, 5 | ||||

| Elysia cf. pusilla* | • | • | 5 | ||||||||

| Elysia sp. 1 | • | • | • | 5 | |||||||

| Elysia sp. 2 | • | • | • | • | 5 | ||||||

| Limapontiidae | Placida cf. dendritica* | • | 5 | ||||||||

| Hermaeidae | Polybranchia mexicana* | • | 5 | ||||||||

| Caliphylla sp. | • | 5 | |||||||||

| Hermaea sp. | • | 5 | |||||||||

| Total | 3 | 14 | 1 | 25 | 27 | 10 | 18 | 1 | 3 |

Figure 2. New records of sea slugs for Oaxaca. A, Berthellina ilisima; B, Berthella sp.; C, Pleurobranchus digueti; D, Dorididae sp. 1; E, Doris sp.; F, Diaulula nayarita; G, Discodoris ketos; H, Geitodoris mavis; I, Polycera anae; J, Polycera cf. hedgpethi. Scale bar = 5mm. Photos by O.I. González-Romero.

Material examined: 1 organism (14 mm), Montosa. Photographic record only.

Distribution: from Puerto Peñasco, Mexico to Islas Galapagos, Ecuador (Behrens et al., 2022).

Remarks: found on rocks with bryozoan colonies. Behrens et al. (2022) treat this species as Polycera gnupa; however, it is unclear if this nudibranch is different from the widespread species P. hedgpethi.

Tambja abdere Farmer, 1978

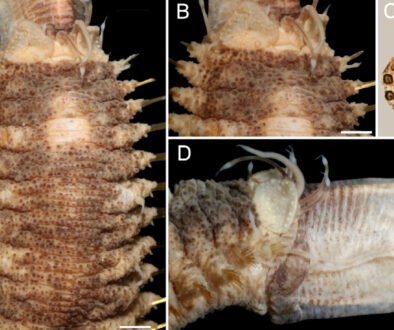

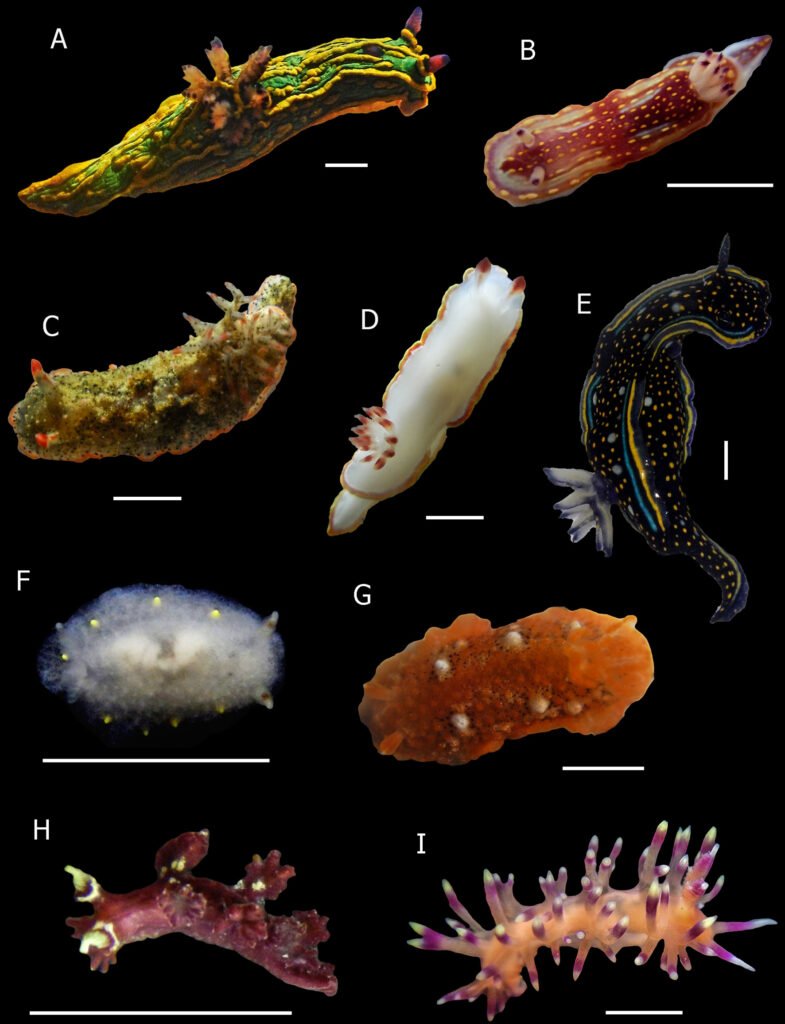

(Fig. 3A)

Material examined: 1 organism (42 mm), Montosa (CNMO7966).

Distribution: from the Gulf of California, Mexico to Costa Rica (Behrens et al., 2022).

Remarks: the specimen was found on rocks at approximately 13 m depth. According to Hermosillo (2007), T. abdere feeds on the bryozoan Sessibugula translucens which lives in zones with low currents.

Family Chromodorididae Bergh, 1891

Felimida sphoni Ev. Marcus, 1971

(Fig. 3B)

Material examined: 1 organism (5 mm), Entrega (CNMO8270). Three organisms (8-14 mm), Arrocito (CNMO8262, CNMO8272). Three organisms (9-12 mm), Conejos (CNMO8263, CNMO8265).

Distribution: from the Gulf of California, Mexico to Ecuador (Behrens et al., 2022).

Remarks: animals were found under rocks near to different unidentified sponges.

Chromolaichma dalli (Bergh, 1879)

(Fig. 3C)

Material examined: 5 organisms (17-32 mm), Montosa (CNMO8259). One organism (5 mm), Conejos (CNMO8264).

Distribution: from Islas San Benito, Baja California to Islas Galapagos, Ecuador (Behrens et al., 2022).

Remarks: larger specimens were found at approximately 15 m depth. Matsuda and Gosliner (2018) categorized C. dalli under a temporal nomenclatural name that needs further taxonomic analysis.

Chromolaichma sedna (Ev. Marcus & Er. Marcus, 1967)

(Fig. 3D)

Material examined: 1 organism (31 mm), Montosa (CNMO8278).

Distribution: from the Gulf of California, Mexico to Ecuador (Behrens et al., 2022).

Remarks: Verdín-Padilla et al. (2010) reported that C. sedna is a polyphagous species that may feed on 16 sponge species.

Felimare agassizii (Bergh, 1894)

(Fig. 3E)

Material examined: 2 organisms (9, 32 mm), Entrega (CNMO8276, CNMO8281). Four organisms (32-55 mm), Arrocito (CNMO8279, CNMO8280, CNMO8282, CNMO8283). One organism (14 mm), Montosa (CNMO8275).

Distribution: from the Gulf of California, Mexico to Islas Galapagos, Ecuador (Behrens et al., 2022).

Remarks: Verdín-Padilla et al. (2010) reported that F. agassizii has a polyphagous diet feeding on 9 sponge species.

Family Cadlinidae Bergh, 1891

Cadlina sp.

(Fig. 3F)

Material examined: 5 organisms (4-5 mm), Entrega. One organism (3 mm), Arrocito. Two organisms (4 mm), Conejos. Photographic record only.

Distribution: from Baja California, Mexico to Panama (Behrens et al., 2022).

Diagnosis: oval translucent white body with 4-5 rounded yellow glands around the mantle at each side of the body, simulating an inner semi-oval. The rhinophores are white with a red band in the centre.

Remarks: the specimens were found on white sponges. Specimens resemble Cadlina sp. in Camacho-García et al. (2005), Bertsch and Aguilar Rosas (2016) and Behrens et al. (2022). This undescribed species has been reported in several locations for the Pacific east coast such as Islas Tres Marías (Hermosillo, 2009), Revillagigedo (Hermosillo & Gosliner, 2008), Bahía de Banderas (Hermosillo, 2011), Acapulco (Flores-Rodríguez et al., 2017) and Costa Rica (Camacho-García et al., 2005).

Family Dendrodorididae O’Donoghue, 1924 (1864)

Doriopsilla janaina Er. Marcus and Ev. Marcus, 1967

(Fig. 3G)

Material examined: 1 organism (18 mm), Entrega (CNMO8022). Two organisms (13, 28 mm), Conejos (CNMO8014, CNMO7985).

Distribution: from Baja California, Mexico to Islas Galapagos, Ecuador (Behrens et al., 2022).

Remarks: 1 specimen was found on brown algae. Although there are reports of the gregarious behaviour of these animals (Hermosillo et al., 2006), they were found individually in our surveys.

Suborder Cladobranchia

Family Hancockiidae MacFarland, 1923

Hancockia californica MacFarland, 1923

(Fig. 3H)

Material examined: 3 organisms (5-11 mm), Arrocito (CNMO7968).

Distribution: from Big Lagoon, California to Costa Rica (Behrens et al., 2022).

Remarks: the specimens were found on green algae. Even though the 3 specimens were collected on the same algae, they presented colour variations in their bodies, from transparent brown to reddish-brown.

Family Flabellinidae Bergh, 1889

Coryphellina marcusorum (Gosliner & Kuzirian, 1990)

(Fig. 3I)

Material examined: 6 organisms (6-18 mm), Montosa (CNMO7976).

Distribution: from Isla San Diego, Baja California to Islas Galapagos, Ecuador (Behrens et al., 2022).

Remarks: specimens were observed at more than 15 m depth. Animals feed on hydroids of the genus Eudendrium (Camacho-García et al., 2005).

Samla telja (Ev. Marcus & Er. Marcus, 1967)

Figure 3. New records of sea slugs for Oaxaca. A, Tambja abdere; B, Felimida sphoni; C, Chromolaichma dalli; D, Chromolaichma sedna; E, Felimare agassizii; F, Cadlina sp; G, Doriopsilla janaina; H, Hancockia californica; I, Coryphellina marcusorum. Scale bar = 5 mm. Photos by O.I. González-Romero.

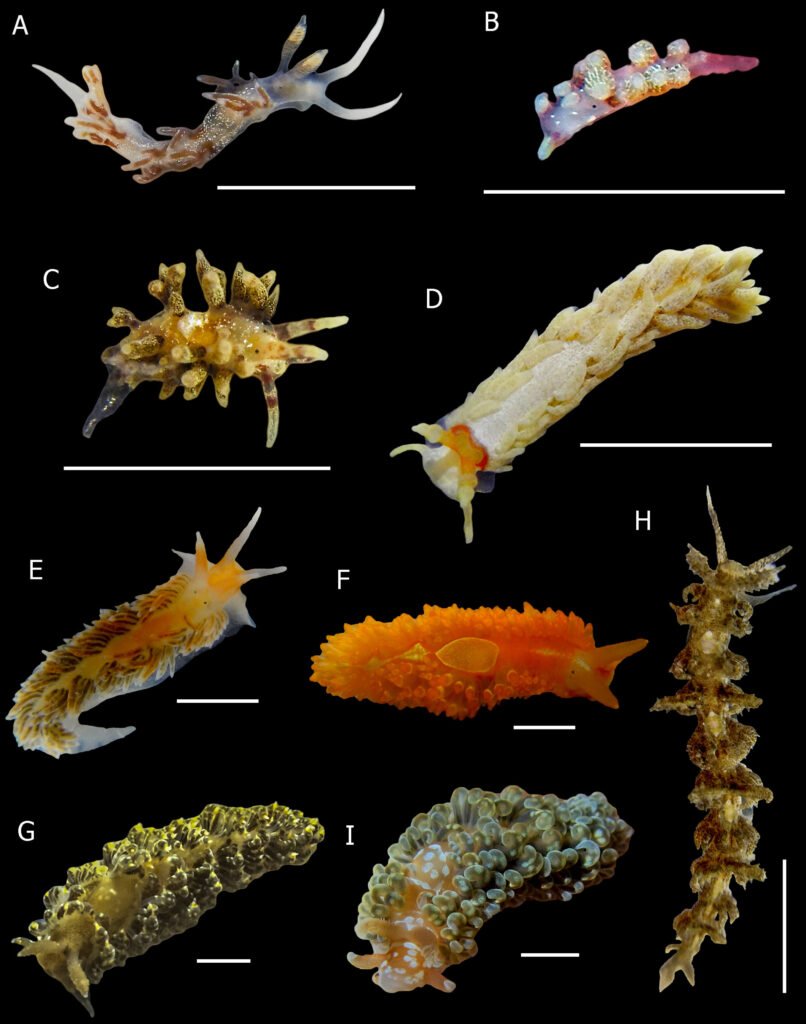

(Fig. 4A)

Material examined: 1 organism (9 mm), Arrocito (CNMO7971). One organism (8 mm), Montosa (CNMO7967).

Distribution: from Puerto Peñasco, Mexico to Islas Galapagos, Ecuador (Behrens et al., 2022).

Remarks: organisms found on hydroids during daytime as reported by Behrens (2022).

Family: Cuthonidae Odhner, 1934

Cuthona sp. 1

(Fig. 4B)

Material examined: 1 organism (3 mm), Arrocito. Photographic record only.

Distribution: from Puerto Vallarta, Mexico to Islas Catalinas, Costa Rica (Camacho-García et al., 2005).

Diagnosis: translucent whitish body with several opaque white spots. The cerata are globose and have longitudinal yellowish lines with a reddish colour on the base. The smooth rhinophores and the oral tentacles are white coloured on the tips and have a reddish-brown band on the base.

Remarks: juvenile specimen found on hydroids with S. telja individuals. Our species diagnosis match Cuthona sp. 3 in Camacho-García et al. (2005). Before this work, this undescribed species had been reported only in 2 localities that correspond to its geographic distribution limits.

Cuthona sp. 2

(Fig. 4C)

Material examined: 1 organism (5 mm), Agustín. Photographic record only.

Distribution: San Agustín, Bahías de Huatulco, Oaxaca (this study).

Diagnosis: light orange body with multiple little white spots. The pericardial area is swollen and has a distinctive white patch. The cerata colour base is brown with several little yellow dots. The smooth rhinophores have orange freckles and an orange band near the tips. The oral tentacles are shorter than the rhinophores and have 2 distinctive orange bands, 1 on the base and the other near the centre.

Remarks: the animal was found near egg masses, possibly just laid by the observed specimen. The observed characters in the organism allowed its identification only to the genus level. Specimen diagnosis did not match any recorded species in the literature.

Family Aeolidiidae Gray, 1827

Bulbaeolidia sulphurea Caballer and Ortea, 2015

(Fig. 4D)

Material examined: 4 organisms (4-12 mm), Agustín (CNMO7975, CNMO7995, CNMO8001).

Distribution: from Puerto Vallarta, Mexico to Islas Galapagos, Ecuador (Behrens et al., 2022).

Remarks: 1 specimen was found on green algae. This species feeds on anemones (Behrens et al., 2022).

Anteaeolidiella chromosoma (Cockerell & Eliot, 1905)

(Fig. 4E)

Material examined: 8 organisms (15-22 mm), Agustín (CNMO7973, CNMO8002, CNMO8005).

Distribution: from Morro Bay, California to Islas Galapagos, Ecuador (Camacho-García et al., 2005).

Remarks: specimens were found under rocks and near coral polyps.

Anteaeolidiella ireneae Carmona et al., 2014

(Fig. 4F)

Material examined: 1 organism (21 mm), Entrega (CNMO8017).

Distribution: from Isla Socorro, Mexico to Panama (Carmona et al., 2014a).

Remarks: feeds on anemones (Behrens et al., 2022).

Baeolidia moebii Bergh, 1888

(Fig. 4G)

Material examined: 1 organism (27 mm), Agustín. Photographic record only.

Distribution: from the Gulf of California, Mexico to Panama (Hermosillo et al., 2006).

Remarks: found under bivalve shells in shallow water (2 m).

Limenandra confusa Carmona et al., 2014

(Fig. 4H)

Material examined: 2 organisms (16, 18 mm), Arrocito (CNMO8033).

Distribution: from the Gulf of California, Mexico to Costa Rica (Carmona et al., 2014c).

Remarks: Carmona et al. (2014c) report that this species feeds on small anemones.

Spurilla braziliana MacFarland, 1909

(Fig. 4I)

Material examined: 1 organism (24 mm), Arrocito. Photographic record only.

Distribution: from Baja California Sur, Mexico to Colombia (Behrens et al., 2022).

Remarks: Carmona et al. (2014b) confirmed that S. braziliana is a widespread species and its presence in the Pacific east coast is probably due to human introduction.

Family Facelinidae Bergh, 1889

Favorinus elenalexiarum García and Troncoso, 2001

Figure 4. New records of sea slugs for Oaxaca. A, Samla telja; B, Cuthona sp. 1; C, Cuthona sp. 2; D, Bulbaeolidia sulphurea; E, Anteaeolidiella chromosoma; F, Anteaeolidiella ireneae; G, Baeolidia moebii; H, Limenandra confusa; I, Spurilla braziliana. Scale bar = 5mm. Photos by O.I. González-Romero.

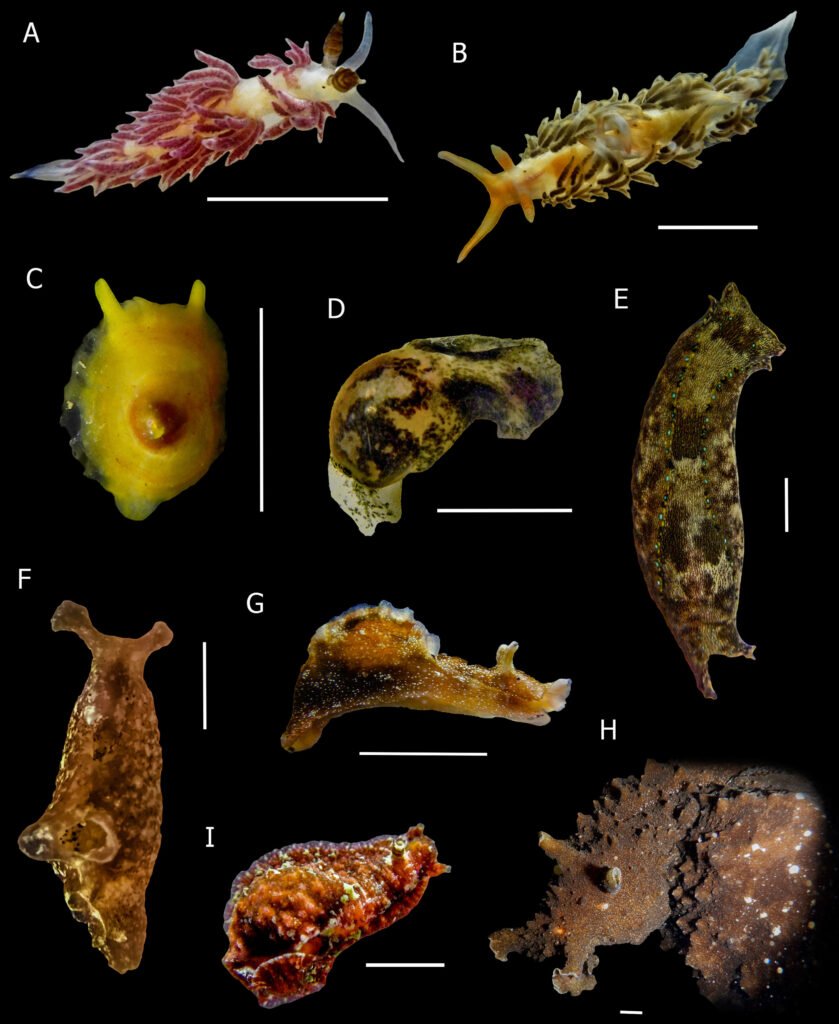

(Fig. 5A)

Material examined: 1 organism (4 mm), Entrega. 1 organism (12 mm), Arrocito. Photographic record only.

Distribution: from the Gulf of California, Mexico to Islas Galapagos, Ecuador (Behrens et al., 2022).

Remarks: specimens found near Aplysia egg masses.

Phidiana lascrucensis Bertsch and Ferreira, 1974

(Fig. 5B)

Material examined: 1 organism (9 mm), Entrega (CNMO7998). Two organisms (8, 12 mm), Arrocito (CNMO7969, CNMO8003). One organism (24 mm), Montosa (CNMO8036). Five organisms (10-21 mm), Conejos (CNMO7980, CNMO8035).

Distribution: from Baja California, Mexico to Panama (Behrens et al., 2022).

Remarks: organisms found under rocks, often observed near specimens of Chiton albolineatus.

Cohort Tectipleura Schrödl, Jörger, Klussmann-Kolb and Wilson, 2011

Subcohort Euopisthobranchia Jörger, Stöger, Kano, Fukuda, Knebelsberger and Schrödl, 2010

Order Umbraculida, Odhner, 1939

Family Tylodinidae Gray, 1847

Tylodina fungina Gabb, 1865

(Fig. 5C)

Material examined: 2 organisms (6, 8 mm), Arrocito (CNMO7994, CNMO8030).

Distribution: from Baja California, Mexico to Islas Galapagos, Ecuador (Hermosillo et al., 2006).

Remarks: Tylodina fungina has a highly specialist diet, feeding on the sponge Aiolochroia thiona and Aplysina gerardogreeni (Behrens et al., 2022; Verdín-Padilla et al., 2010).

Order Cephalaspidea Fischer, 1883

Family Haminoeidae Pilsbry, 1895

Haminoea sp.

(Fig. 5D)

Material examined: 2 organisms (8, 10 mm), Arrocito (CNMO7958).

Distribution: from Bahía de Banderas, Mexico to Peru (Behrens et al., 2022).

Diagnosis: body oval. White cream body, with irregular dark brown patches. The animals have an inverted “V” stain in the cephalic area between the eyes. The body is surrounded by multiple orange and light brown dots.

Remarks: specimens found on marine brown cyanobacteria. This species was firstly identified as the Indo-Pacific species Lamprohaminoea ovalis by Valdés and Camacho-García (2004). However, recently phylogenetic analysis has shown that the specimens in the Pacific east coast are an undescribed species more related to the Atlantic and Pacific species of the genus Haminoea (Oskars & Malaquias, 2019, 2020).

Family Aglajidae Pilsbry, 1895

Navanax aenigmaticus (Bergh, 1893)

(Fig. 5E)

Material examined: 5 organisms (30-44 mm), Entrega (CNMO7996, CNMO7999, CNMO8007). Two organisms (21, 33 mm), Arrocito (CNMO8032).

Distribution: from Baja California, Mexico to Chile (Behrens et al., 2022).

Remarks: collected specimens presented different body colour variations from black, brown, and pink with cream or whitish spots. According to Ornelas-Gatdula et al. (2012), colouration differences on N. aenigmaticus could be probably influenced by environmental factors.

Order Aplysiida

Family Aplysiidae Lamarck, 1809

Aplysia cf. cedrosensis

(Fig. 5F)

Material examined: 1 organism (22 mm), Conejos (CNMO7978).

Distribution: from Bahía de los Angeles, Baja California to Playa Conejos, Bahías de Huatulco, Oaxaca.

Remarks: juvenile specimen found under rocks near red algae. Our diagnosis matched the species A. cedrosensis in Hermosillo et al. (2006). However, Behrens et al. (2022) state that this species might be a synonym of the California black sea hare Aplysia vaccaria. Before this work, the southern distribution of A cedrosensis in the Pacific east coast was reported for Parque de la Reina, Acapulco (Flores-Rodríguez et al., 2017), approximately 440 km northeast from Playa Conejos, Oaxaca.

Aplysia hooveri Golestani et al., 2019

(Fig. 5G)

Material examined: 72 organisms (3-16 mm), Entrega (CNMO7961-7963, CNMO7986, CNMO8010, CNMO8021, CNMO8026, CNMO8034). Two organisms (6, 7 mm), Arrocito (CNMO7972). Five organisms (5-12 mm), Conejos (CNMO7982, CNMO7993).

Distribution: from Baja California, Mexico to Islas Galapagos, Ecuador (Valdés, 2019).

Remarks: this species was highly abundant in some localities of the study area; it was usually associated with red and brown algae.

Dolabella cf. auricularia (Lightfoot, 1786)

(Fig. 5H)

Material examined: 1 organism (180 mm), Agustín. One organism (210 mm), Entrega. Photographic record only.

Distribution: from the Gulf of California, Mexico to Ecuador (Zamora-Silva & Naranjo-García, 2008).

Remarks: found on algae at approximately 10 m depth. According to Behrens et al. (2022) there is molecular evidence that confirms that Dolabella auricularia is a species complex.

Dolabrifera nicaraguana Pilsbry, 1896

(Fig. 5I)

Figure 5. New records of sea slugs for Oaxaca. A, Favorinus elenalexiarum; B, Phidiana lascrucensis; C, Tylodina fungina; D, Haminoea sp.; E, Navanax aenigmaticus; F. Aplysia cf. cedrosensis; G, Aplysia hooveri; H, Dolabella cf. auricularia; I, Dolabrifera nicaraguana. Scale bar = 5 mm. Photos by O.I. González-Romero.

Material examined: 1 organism (14 mm), Entrega (CNMO7960).

Distribution: from Bahía de las Cruces, Baja California to Tumbes, Peru (Valdés et al., 2018).

Remarks: cryptic specimen found on rhodolith beds.

Phyllaplysia padinae Williams and Gosliner, 1973

(Fig. 6A)

Material examined: 4 organisms (8-18 mm), Conejos (CNMO8277, CNMO8268, CNMO8269).

Distribution: from the Gulf of California, Mexico to Islas Galapagos, Ecuador (Camacho-García et al., 2005).

Remarks: the specimens were found attached to algae of the genera Padina and Caulerpa.

Stylocheilus rickettsi (MacFarland, 1966)

(Fig. 6B)

Material examined: 29 organisms (5-29 mm), Entrega (CNMO7959, CNMO7997, CNMO8008, CNMO8018, CNMO8023, CNMO8024, CNMO8027). Five organisms (6-38 mm), Arrocito (CNMO7957, CNMO7970).

Distribution: from Baja California, Mexico to Islas Galapagos, Ecuador (Bazzicalupo et al., 2020).

Remarks: the specimens were found on rocks and on different unidentified green, red, and brown algae.

Subcohort Panpulmonata Jörge et al., 2010

Superorder Sacoglossa Ihering, 1876

Family Oxynoidae Stoliczka, 1868 (1847)

Lobiger cf. souverbii Fischer, 1857

(Fig. 6C)

Material examined: 1 organism (6 mm), Entrega (CNMO8015). One organism (9 mm), Conejos (CNMO7983).

Distribution: Baja California Sur, Mexico to Islas Galapagos, Ecuador (Behrens et al., 2022).

Remarks: specimens were found associated with algae of the genus Caulerpa as mentioned in the literature (Behrens et al., 2022; Camacho-García et al., 2005). Due to the original description of L. souverbii in the Caribbean region, this sacoglossan is suspected to be a different species.

Oxynoe aliciae Krug et al., 2018

(Fig. 6D)

Material examined: 6 organisms (4-9 mm), Entrega (CNMO8009, CNMO8016).

Distribution: from Baja California Sur, Mexico to Islas Galapagos, Ecuador (Behrens et al., 2022).

Remarks: specimens found as hosts on the algae Caulerpa as mentioned by Krug et al. (2018).

Family Plakobranchidae Gray, 1840

Elysia cf. pusilla (Bergh, 1871)

(Fig. 6E)

Material examined: 3 organisms (8-11 mm), Arrocito (CNMO8004). Ten organisms (8-10 mm), Conejos (CNMO7977, CNMO8000, CNMO8013).

Distribution: from Mexico to Costa Rica (Behrens et al., 2022).

Remarks: cryptic specimens were found attached to algae of the genus Halimeda as mentioned in the literature (Behrens et al., 2022; Camacho-García et al., 2005). This species is presumed to be different from E. pusilla, which was originally described in the Indo-Pacific region (Behrens et al., 2022).

Elysia sp. 1

(Fig. 6F)

Material examined: 4 organisms (6-10 mm), Arrocito. Twenty-seven organisms (5-14 mm), Conejos. Photographic record only.

Distribution: from Bahía de Banderas, Mexico to Panama (Hermosillo et al., 2006).

Diagnosis: elongated olive-greenish body. The rolled rhinophores are yellow whitish with light brown patches. The parapodia are strongly folded with an opening in the centre. Some specimens have a white spot in the base of the rhinophores.

Remarks: specimens were found associated with algae of the genus Halimeda. Our diagnosis resembles the species Elysia sp. 1 in Camacho-García et al. (2005) and Hermosillo et al. (2006). There are numerous records of this undescribed species in the Pacific east coast: Bahía de Banderas (Hermosillo, 2011), Ixtapa, Guerrero (Hermosillo & Behrens, 2005), Papagayo and Parque de la Reina, Acapulco (Flores-Rodríguez et al., 2017), Playa Avellanas and San Pedrillo, Costa Rica (Camacho-García et al., 2005) and Panama (Hermosillo et al., 2006).

Elysia sp. 2

(Fig. 6G)

Material examined: 4 organisms (13-24 mm), Entrega. Two organisms (19, 22 mm), Arrocito. 8 organisms (12-24 mm), Conejos. Photographic record only.

Distribution: from Islas Revillagigedo, Mexico to Costa Rica (Behrens et al., 2022).

Diagnosis: elongated light-greenish body with several white and dark green specks. The rhinophores are smooth, large, and rolled. The convoluted parapodia are folded with several rounded whitish papillae on the edges. Adult specimens have a purple-pinkish colouration along the margin of the parapodia and in the basis of the rhinophores.

Remarks: some specimens were found on red and green algae of the genus Halimeda and Caulerpa. Our diagnosis matched the species Elysia sp. 2 in Camacho-García et al. (2005) and Elysia sp. in Behrens et al. (2022). This undescribed species was previously documented in multiple locations in the Pacific east coast: Bahía de Banderas (Hermosillo, 2011), Islas Revillagigedo (Hermosillo & Gosliner, 2008), Isla Clipperton (Kaiser, 2007), Ixtapa, Guerrero (Hermosillo & Behrens, 2005) and Costa Rica (Camacho-García et al., 2005).

Family Limapontiidae Gray, 1847

Placida cf. dendritica (Alder and Hancock, 1843)

(Fig. 6H)

Material examined: 3 organisms (3-5 mm), Entrega (CNMO8019).

Distribution: from the Gulf of California to La Entrega, Bahías de Huatulco, Oaxaca.

Remarks: specimens were found on algae of the genus Bryopsis. Before this work, the southern distribution of P. dendritica in the Pacific east coast was known for Bahía de Banderas, Nayarit (Hermosillo, 2011), approximately 1,200 km northeast from La Entrega, Oaxaca. It is suspected that P. dendritica might be a species complex that encompasses 2 different species in the region (Behrens et al., 2022).

Family Hermaeidae H. Adams and A. Adams, 1854

Polybranchia mexicana Medrano et al., 2018

(Fig. 6I)

Material examined: 1 organism (48 mm), Conejos (CNMO7992).

Distribution: from Baja California, Mexico to Islas Galapagos, Ecuador (Medrano et al., 2018).

Remarks: specimen found under rocks at daylight supporting the reports of the nocturnal habits of the species (Behrens et al., 2022).

Caliphylla sp.

(Fig. 6J)

Material examined: 4 organisms (5-14 mm), Entrega. Photographic record only.

Distribution: from La Entrega, Mexico to Islas Galapagos, Ecuador.

Diagnosis: elongated translucent green body with multiple little dark green and white dots. The bifid rhinophores, the head and the cerata have visible dark green ramified digestive branches. The elongated cerata are flattened and pointed. Some specimens may have a white speck between the eyes and in the posterior part of the head.

Remarks: some specimens were found on algae of the genus Bryopsis. Our diagnosis coincides with the undescribed species Caliphylla sp. in Camacho-García et al. (2005), which has been previously reported in a few localities from Costa Rica and Ecuador.

Hermaea sp.

(Fig. 6K)

Material examined: 1 organism (5 mm), Entrega. Photographic record only.

Distribution: from La Entrega, Oaxaca, Mexico to Playa Real, Guanacaste, Costa Rica.

Diagnosis: cream coloured body with multiple dark green flecks. Rhinophores are auriculate. The arrow-head shape cerata are covered with several white dots and red-brownish ramified digestive branches are visible throughout.

Remarks: the specimen was found on filamentous red algae. Our diagnosis resembles the species Hermaea sp. 3 in Camacho-García et al. (2005), which has been previously reported in Costa Rica.

Figure 6. New records of sea slugs for Oaxaca. A, Phyllaplysia padinae; B, Stylocheilus rickettsi; C, Lobiger cf. souverbii; D, Oxynoe aliciae; E, Elysia cf. pusilla; F, Elysia sp. 1; G, Elysia sp. 2; H, Placida cf. dendritica; I, Polybranchia mexicana; J, Caliphylla sp.; K, Hermaea sp. Scale bar = 5 mm. Photos by O.I. González-Romero.

Discussion

In this study we added 48 sea slug records, increasing by 83% the knowledge of sea slugs’ diversity for Oaxaca, from 10 to 58 species (Table 2). Also, the records presented in this study represent almost 11% of the total sea slug species previously known for the Eastern Pacific, from Alaska to Peru (Behrens et al., 2022). Among the sea slug fauna from Oaxaca, the order Nudibranchia is the most diverse encompassing more than half of the registered species, which is a general trend observed worldwide and in other localities from the Tropical Eastern Pacific (TEP) (García-Méndez & Camacho-García, 2016; Gosliner, 1991; Hermosillo, 2004; Spalding et al., 2007), and might be explained due to phylogenetic, historical and functional variables within the group (Bertsch, 2010). In contrast with other localities on the Pacific coast of Mexico (Table 3), the total number of species recorded in Oaxaca is similar to those reported for Isla Tres Marías, Nayarit (52 spp.), which is a relatively lower species richness compared with other works that involve higher sampling effort and/or more extensive study areas (Angulo-Campillo, 2005; Bertsch, 2014; Hermosillo, 2011; Hermosillo & Behrens, 2005). Moreover, the percentage of shared species between Revillagigedo, Colima and Oaxaca is higher (57.1%) than in other localities; however, this amount could be inaccurate due to the underestimated sea slug diversity in Islas Revillagigedo pointed out by Hermosillo and Gosliner (2008).

Overall, almost all the new sea slug records in this study are endemic to the Panamic biogeographic province (Briggs & Bowen, 2012), with some exceptions previously remarked that are also distributed on the Western Atlantic and/or the Indo-Pacific regions. Most of these exceptions belong to species complex that have not been resolved yet (Behrens et al., 2022), but others have a widespread natural distribution, or they have been introduced possibly by humans’ influence, as it has been suggested for S. braziliana (Carmona et al., 2014b). Interestingly, all the species previously reported for Oaxaca by Rodríguez-Palacios et al. (1988) (see Table 2) are not distributed in the Panamic province nor any warm waters of the Pacific east coast. Therefore, these records should be treated with caution as these species might have been misidentified due to the lack of specific field guides and accessible literature related with the sea slug fauna for this region in the past.

Coral reef communities, including those inhabiting the TEP, are one of the most thriving habitats for sea slugs, as they encompass a net of biological associations that increase their diversity and inherent productivity (Sanvicente-Añorve et al., 2012; Sreeraj et al., 2013). In general, we found a higher species richness in localities with greater heterogeneity in their substrate composition (Table 1), possibly providing more habitats for sea slugs to succeed in this area. San Agustín, which is inside a Natural Protected Area, did not show a higher species richness compared to other localities. However, the number of species in this locality is underestimated, as we could not perform algae collection as an indirect search method; additionally, other variables need to be analysed to determine whether there is a significant difference in the sea slug diversity between protected and non-protected areas.

The continuous discovery of undescribed sea slug species in the TEP, such as the ones reported in this work: Berthella sp., Dorididae sp., Doris sp., and Cuthona sp. 2 has been a common issue, even in recent years. Phylogenetic and systematic studies have helped to elucidate the status of certain sea slug taxa (e.g., Bazzicalupo et al., 2020; Golestani et al., 2019; Krug et al., 2018; Medrano et al., 2018; Valdés et al., 2018), and represent important efforts to better understand the diversity of the sea slug fauna in the TEP. Nonetheless, there are species recorded more than a decade ago, such as Cadlina sp., Cuthona sp. 1, Elysia sp. 1, Elysia sp. 2, Caliphylla sp. and Hermaea sp. that remain undescribed. In the same way, some studies have found uncertainties in described species related to their geographic distribution. For instance, Behrens et al. (2022) state that Aplysia cf. cedrosensis and Placida cf. dendritica are given names that belong to 2 or more undescribed species that inhabit different biogeographic provinces. The extension of the distribution for those species reported in this work could confirm that they are different species indeed, and further taxonomic studies regarding the description and distribution of each species need to be done.

Table 3

Studies on sea slug diversity from the Pacific coast of Mexico. Shared species refer to those species present in other localities and this study (Huatulco).

| Locality | Number of species | Number of shared species (%) | Reference |

| Bahía de los Angeles, Baja California | 117 | 26 (22.2) | Bertsch (2014) |

| Baja California Sur | 117 | 31 (26.4) | Angulo-Campillo (2005) |

| Bahía de Banderas, Nayarit-Jalisco | 146 | 44 (30.1) | Hermosillo (2011) |

| Islas Tres Marías, Nayarit | 52 | 27 (51.9) | Hermosillo (2009) |

| Revillagigedo, Colima | 42 | 24 (57.1) | Hermosillo and Gosliner (2008) |

| Colima, Michoacán and Guerrero | 76 | 38 (50) | Hermosillo and Behrens (2005) |

| Acapulco, Guerrero | 63 | 27 (42.8) | Flores-Rodríguez et al. (2017) |

This study updates the knowledge of the sea slug fauna of Oaxaca and the southern Pacific coast of Mexico; however, many unexplored localities in this region still need to be studied. Since this region could be a potential hotspot of marine biodiversity (Bastida-Zavala et al., 2013), further efforts to find sea slugs are needed. Future samplings involving SCUBA diving on different habitats such as lagoons, mangroves, and rocky shores at different times of the day may help to increase this inventory. This work also contributes to the biological inventory of Parque Nacional Huatulco, which is essential to determine future perspectives in the conservation planning and management of this and other Natural Protected Areas (Bezaury-Creel & Gutiérrez, 2009).

Acknowledgements

We thank Parque Nacional Huatulco for allowing us the entrance to perform the surveys in the locality of San Agustín; OGR acknowledges Comisión Nacional de Becas de Educación Superior, SEP for the financial support as an undergraduate student; XGV acknowledges Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (Conacyt) her PhD scholarship (CVU: 564148). We thank A. Valdés, P. Krug and S. Medrano, who helped with the identification of some organisms, and E. Naranjo-García for providing a space to work in her laboratory. We thank F. Pérez, M. Pérez, and M. A. Arriaga for their hospitality and support in performing this study; to the staff of “Buceo Anfibios Huatulco” and all the people who helped us in the surveys, especially E. Molina, L. Jiménez, A. García and A. Barrera.

References

Alexander, T. J., Barrett, N., Haddon, M., & Edgar, G. (2009). Relationships between mobile macroinvertebrates and reef structure in a temperate marine reserve. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 389, 31–44. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps08210

Angulo-Campillo, O. (2005). A four-year survey of the opisthobranch fauna (Gastropoda, Opisthobranchia) from Baja California Sur. Vita Malacologica, 3, 43–50.

Barrientos-Luján, N. A., Rodríguez-Zaragoza, F. A., & López-Pérez, A. (2021). Richness, abundance and spatial heterogeneity of gastropods and bivalves in coral ecosystems across the Mexican Tropical Pacific. Journal of Molluscan Studies, 87, eyab004. https://doi.org/10.1093/mollus/eyab004

Bastida-Zavala, J. R., García-Madrigal, M. S., Rosas-Alquicira, E. F., López-Pérez, R. A., Benítez-Villalobos, F., Meraz-Hernando, J. F. et al. (2013). Marine and coastal biodiversity of Oaxaca, Mexico. Check List, 9, 329–390. https://doi.org/10.15560/9.2.329

Bazzicalupo, E., Crocetta, F., Gosliner, T. M., Berteaux-Lecellier, V., Camacho-García, Y. E., Sneha Chandran, B. K. et al. (2020). Molecular and morphological systematics of Bursatella leachii de Blainville, 1817 and Stylocheilus striatus Quoy & Gaimard, 1832 reveal cryptic diversity in pantropically distributed taxa (Mollusca: Gastropoda: Heterobranchia). Invertebrate Systematics, 34, 535–568. https://doi.org/10.1071/IS19056

Behrens, D. W. (2005). Nudibranch behaviour. Jacksonville, FL: New World Publications.

Behrens, D. W., Fletcher, K., Hermosillo, A., & Jensen, G. C. (2022). Nudibranchs and sea slugs of the Eastern Pacific. Bremerton, Washington: MolaMarine.

Benkendorff, K., & Davis, A. R. (2002). Identifying hotspots of molluscan species richness on rocky intertidal reefs. Biodiversity and Conservation, 11, 1959–1973. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020886526259

Bertsch, H. (2010). Biogeography of Northeast Pacific opisthobranchs: comparative faunal province studies between Point Conception, California, USA, and Punta Aguja, Piura, Perú. In L. J. Rangel-Ruiz, J. Gamboa-Aguilar, S. L. Arriaga-Weiss, & W. M. Contreras Sánchez (Eds.), Perspectivas en malacología mexicana (pp. 219–259). Villahermosa: División Académica de Ciencias Biológicas, Universidad Juárez Autónoma de Tabasco.

Bertsch, H. (2014). Biodiversity in the Reserva de la Biosfera Bahía de los Ángeles y Canales de Ballenas y Salsipuedes: naming of a new genus, range extensions and new records, and species list of Heterobranchia (Mollusca: Gastropoda), with comments on biodiversity conservation within marine reserves. The Festivus, 46, 158–177. https://doi.org/10.54173/f465158

Bertsch, H., & Aguilar-Rosas, L. E. (2016). Invertebrados marinos del noroeste de México / Marine invertebrates of Northwest Mexico. Ensenada, Baja California: Instituto de Investigaciones Oceanológicas, UABC.

Bezaury-Creel, J., & Gutiérrez, D. (2009). Áreas naturales protegidas y desarrollo social en México. In R. Dirzo, R. González, & I. J. March (Eds.), Capital natural de México: estado de conservación y tendencias de cambio, Vol. II. Estado de conservación y tendencias de cambio (pp. 385–431). Ciudad de México: Comisión Nacional para el Conocimientos y Uso de la Biodiversidad.

Bouchet, P., Rocroi, J. P., Hausdorf, B., Kaim, A., Kano, Y., Nützel, A. et al. (2017). Revised classification, nomenclator and typification of gastropod and monoplacophoran families. Malacologia, 61, 1–526. https://doi.org/10.4002/040.061.0201

Briggs, J. C., & Bowen, B. W. (2012). A realignment of marine biogeographic provinces with particular reference to fish distributions. Journal of Biogeography, 39, 12–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2011.02613.x

Camacho-García, Y. E., Gosliner, T. M., & Valdés, Á. (2005). Guía de campo de las babosas marinas del Pacífico este tropical. San Francisco, CA: California Academy of Sciences.

Carmona, L., Bhave, V., Salunkhe, R., Pola, M., Gosliner, T. M., & Cervera, J. L. (2014a). Systematic review of Anteaeolidiella (Mollusca, Nudibranchia, Aeolidiidae) based on morphological and molecular data, with a description of three new species. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 171, 108–132. https://doi.org/10.1111/zoj.12129

Carmona, L., Lei, B. R., Pola, M., Gosliner, T. M., Valdés, Á., & Cervera, J. L. (2014b). Untangling the Spurilla neapolitana (Delle Chiaje, 1841) species complex: a review of the genus Spurilla Bergh, 1864 (Mollusca: Nudibranchia: Aeolidiidae). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 170, 132–154. https://doi.org/10.1111/zoj.12098

Carmona, L., Pola, M., Gosliner, T. M., & Cervera, J. L. (2014c). The end of a long controversy: Systematics of the genus Limenandra (Mollusca: Nudibranchia: Aeolidiidae). Helgoland Marine Research, 68, 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10152-013-0367-y

Conanp (Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas). (2003). Programa de Manejo Parque Nacional Huatulco, México. Dirección General de Manejo para la Conservación, Ciudad de México: Conanp. https://www.conanp.gob.mx/que_hacemos/pdf/programas_manejo/huatulco.pdf

Dean, L. J., & Prinsep, M. R. (2017). The chemistry and chemical ecology of nudibranchs. Natural Product Reports, 34, 1359–1390. https://doi.org/10.1039/c7np00041c

Fisch, K. M., Hertzer, C., Böhringer, N., Wuisan, Z. G., Schillo, D., Bara, R. et al. (2017). The potential of Indonesian heterobranchs found around Bunaken Island for the production of bioactive compounds. Marine Drugs, 15, 384. https://doi.org/10.3390/md15120384

Flores-Rodríguez, P., Flores-Garza, R., García-Ibáñez, S., Valdés-González, A., Martínez-Ríos, B., Mora-Marín, Y. et al. (2017). Riqueza, composición de la comunidad y similitud de las especies bentónicas de la subclase Opisthobranchia (Mollusca: Gastropoda) en cinco sitios del litoral de Acapulco, México. Revista de Biología Marina y Oceanografía, 52, 67–80. https://doi.org/10.4067/s0718-19572017000100005

García-Méndez, K., & Camacho-García, Y. E. (2016). New records of heterobranch sea slugs (Mollusca: Gastropoda) from Isla del Coco National Park, Costa Rica. Revista de Biología Tropical, 64, 205–279. https://doi.org/10.15517/rbt.v64i1.23449

Gladstone, W. (2002). The potential value of indicator groups in the selection of marine reserves. Biological Conservation, 104, 211–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3207(01)00167-7

Golestani, H., Crocetta, F., Padula, V., Camacho-García, Y., Langeneck, J., Poursanidis, D. et al. (2019). The little Aplysia coming of age: from one species to a complex of species complexes in Aplysia parvula (Mollusca: Gastropoda: Heterobranchia). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 187, 279–330. https://doi.org/10.1093/zoolinnean/zlz028

Goodheart, J., & Bely, A. (2017). Sequestration of nematocysts by divergent cnidarian predators: mechanism, function, and evolution. Invertebrate Biology, 136, 75–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/ivb.12154

Gosliner, T. M. (1991). The opisthobranch gastropod fauna of the Galápagos Islands. In M. J. James (Ed.), Galápagos marine invertebrates: taxonomy, biogeography and evolution in Darwin’s islands (pp. 281–305). Boston, MA: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-0646-5_14

Gosliner, T., Valdés, Á., & Behrens, D. (2018). Nudibranch and sea slug identification: Indo-Pacific. Jacksonville, FL: New World Publications.

Händeler, K., Grzymbowski, Y. P., Krug, P. J., & Wägele, H. (2009). Functional chloroplasts in metazoan cells – a unique evolutionary strategy in animal life. Frontiers in Zoology, 6, 28. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-9994-6-28

Hermosillo, A. (2004). Opisthobranch mollusks of Parque Nacional De Coiba, Panama (Tropical Eastern Pacific). The Festivus, 36, 105–117.

Hermosillo, A. (2007). Historia natural y ecología de Tambja abdere (Marcus y Marcus, 1967) (Mollusca: Opisthobranchia) de Bahía de Banderas. In E. Ríos-Jara, M. C. Esqueda-González, & C. M. Galván-Villa (Eds.), Estudios sobre la malacología y conquiliología en México (pp. 179–180). Guadalajara: Universidad de Guadalajara, México.

Hermosillo, A. (2009). The opisthobranch fauna of Islas Tres Marías, Mexican Pacific. The Festivus, 41, 3–9.

Hermosillo, A. (2011). Species list of opisthobranch mollusks for Bahía de Banderas (Jalisco-Nayarit), Pacific Coast of México. The Festivus, 43, 39–49.

Hermosillo, A., & Behrens, D. W. (2005). The opisthobranch fauna (Gastropoda, Opisthobranchia) of the Mexican states of Colima, Michoacán and Guerrero: filling in the faunal gap. Vita Malacologica, 3, 11–22.

Hermosillo, A., Behrens, D. W., & Ríos-Jara, E. (2006). Opistobranquios de México: guía de babosas marinas del Pacífico, golfo de California y las islas Oceánicas. Guadalajara, Jalisco: Conabio.

Hermosillo, A., & Gosliner, T. M. (2008). The opisthobranch fauna of the Archipiélago de Revillagigedo, Mexican Pacific. The Festivus, 40, 25–34.

Horton, T., Kroh, A., Ahyong, S., Bailly, N., Boyko, C. B., & Brandão, S. N. (2024). World register of marine species. Accessed on 2024-06-05. http://www.marinespecies.org

Holguín-Quiñones, O., & González-Pedraza, A. (1989). Moluscos de la franja costera del estado de Oaxaca, México. Atlas No. 7 CICIMAR, Instituto Politécnico Nacional.

Kaiser, K. L. (2007). The recent molluscan fauna of Île Clipperton. The Festivus, 39, 1–162.

Kandel, E. (1979). Behavioral biology of Aplysia: a contribution to the comparative study of opisthobranch mollusks. San Francisco, CA: W. H. Freeman.

Krug, P. J., Berriman, J. S., & Valdes, A. (2018). Phylogenetic systematics of the shelled sea slug genus Oxynoe Rafinesque, 1814 (Heterobranchia: Sacoglossa), with integrative descriptions of seven new species. Invertebrate Systematics, 32, 950–1003. https://doi.org/10.1071/IS17080

López-Pérez, R., & Hernández-Ballesteros, L. (2004). Coral community structure and dynamics in the Huatulco area, western Mexico. Bulletin of Marine Science, 75, 453–472.

Matsuda, S. B., & Gosliner, T. M. (2018). Molecular phylogeny of Glossodoris (Ehrenberg, 1831) nudibranchs and related genera reveals cryptic and pseudocryptic species complexes. Cladistics, 34, 41–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/cla.12194

Medrano, S., Krug, P. J., Gosliner, T. M., Kumar, A. B., & Valdés, Á. (2018). Systematics of Polybranchia Pease, 1860 (Mollusca: Gastropoda: Sacoglossa) based on molecular and morphological data. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 186, 76–115. https://doi.org/10.1093/zoolinnean/zly050

Ornelas-Gatdula, E., Camacho-García, Y., Schrödl, M., Padula, V., Hooker, Y., Gosliner, T. M. et al. (2012). Molecular systematics of the “Navanax aenigmaticus” species complex (Mollusca, Cephalaspidea): coming full circle. Zoologica Scripta, 41, 374–385. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-6409.2012.00538.x

Oskars, T. R., & Malaquias, M. A. E. (2019). A molecular phylogeny of the Indo-West Pacific species of Haloa sensu lato gastropods (Cephalaspidea: Haminoeidae): Tethyan vicariance, generic diversity, and ecological specialization. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 139, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2019.106557

Oskars, T. R., & Malaquias, M. A. E. (2020). Systematic revision of the Indo-West Pacific colourful bubble-snails of the genus Lamprohaminoea Habe, 1952 (Cephalaspidea: Haminoeidae). Invertebrate Systematics, 34, 727–756. https://doi.org/10.1071/is20026

Pola, M., Sánchez-Benítez, M., & Ramiro, B. (2014). The genus Polycera Cuvier, 1817 (Nudibranchia: Polyceridae) in the eastern Pacific Ocean, with redescription of Polycera alabe Collier & Farmer, 1964 and description of a new species. Journal of Molluscan Studies, 80, 551–561. https://doi.org/10.1093/mollus/eyu049

Ramírez-González, A. (2005). Las bahías de Huatulco, Oaxaca, México: ensayo geográfico ecológico. Ciencia y Mar, 9, 3–20.

Rodríguez-Palacios, C., Mitchell-Arana, L., Sandoval-Díaz, G., Gómez, P., & Green, G. (1988). Los moluscos de las bahías de Huatulco y Puerto Ángel, Oaxaca. Distribución, diversidad y abundancia. Universidad y Ciencia, 5, 85–94.

Sanvicente-Añorve, L., Hermoso-Salazar, M., Ortigosa, J., Solís-Weiss, V., & Lemus-Santana, E. (2012). Opisthobranch assemblages from a coral reef system: the role of habitat type and food availability. Bulletin of Marine Science, 88, 1061–1074. https://doi.org/10.5343/bms.2011.1117

Schejter, L., Rimondino, C., Chiesa, I., Díaz-de Astarloa, J. M., Doti, B., Elías, R. et al. (2016). Namuncurá Marine Protected Area: an oceanic hot spot of benthic biodiversity at Burdwood Bank, Argentina. Polar Biology, 39, 2373–2386. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00300-016-1913-2

Schubert, J., & Smith, S. D. A. (2020). Sea slugs “rare in space and time” but not always. Diversity, 12, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3390/d12110423

Spalding, M. D., Fox, H. E., Allen, G. R., Davidson, N., Ferdaña, Z. A., Finlayson, M. et al. (2007). Marine ecoregions of the World: a bioregionalization of coastal and shelf areas. Bioscience, 57, 573–583. https://doi.org/10.1641/b570707

Sreeraj, C. R., Sivaperuman, C., & Raghunathan, C. (2013). Species diversity and abundance of opisthobranch molluscs (Gastropoda: Opisthobranchia) in the coral reef environments of Andaman and Nicobar Islands, India. In K. Venkataraman, C. Sivaperuman, & C. Raghunathan (Eds.), Ecology and conservation of tropical marine faunal communities (pp. 81–106). Heidelberg, Berlin: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-38200-0_6

Urbano, B., Ortigosa, D., Garcés-Salazar, J., Aristeo, J., González-Liano, M., Álvarez-Cerrillo, L. et al. (2019). Evaluación de la antropización usando a los moluscos como parámetro. In C. P. Ornelas-García, F. Álvarez, & A. Wegier (Eds.), Antropización: primer análisis integral (pp. 199–219). Ciudad de Mexico: IBUNAM/ Conacyt.

Valdés, Á. (2019). Northeast Pacific benthic shelled sea slugs. Zoosymposia, 13, 242–304. https://doi.org/10.11646/zoosymposia.13.1.21

Valdés, Á., Breslau, E., Padula, V., Schrödl, M., Camacho, Y., Malaquias, M. A. E. et al. (2018). Molecular and morphological systematics of Dolabrifera Gray, 1847 (Mollusca: Gastropoda: Heterobranchia: Aplysiomorpha). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 184, 31–65. https://doi.org/10.1093/zoolinnean/zlx099

Valdés, Á., & Camacho-García, Y. E. (2004). “Cephalaspidean” heterobranchs (Gastropoda) from the Pacific coast of Costa Rica. Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences, 55, 459–497.

Verdín-Padilla, C., Carballo, J. L., & Camacho, M. L. (2010). A qualitative assessment of sponge-feeding organisms from the Mexican Pacific Coast. The Open Marine Biology Journal, 4, 39–46. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874450801004010039

Zamora-Silva, A., & Naranjo-García, E. (2008). Los opistobranquios de la Colección Nacional de Moluscos. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 79, 333–342. https://doi.org/10.22201/ib.20078706e.2008.002.568

Ziegler, M., FitzPatrick, S. K., Burghardt, I., Liberatore, K. L., Leffler, A. J., Takacs-Vesbach, C. et al. (2014). Thermal stress response in a dinoflagellate-bearing nudibranch and the octocoral on which it feeds. Coral Reefs, 33, 1085–1099. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-014-1204-8