Eduardo Reyes-Grajales a, b, *, Christian Rico c, John Iverson d, Luis Díaz-Gamboa e, Marco A. López-Luna f, Wilfredo A. Matamoros g

a El Colegio de la Frontera Sur, Departamento Conservación de la Biodiversidad, Doctorado en Ciencias en Ecología y Desarrollo Sustentable, Carretera Panamericana y Periférico Sur s/n, Barrio María Auxiliadora, 29290 San Cristóbal de Las Casas, Chiapas, Mexico

b Turtle Survival Alliance, 1030 Jenkins Road, Charleston, 29407 South Carolina, USA

c Universidad de Ciencias y Artes de Chiapas, Instituto de Ciencias Biológicas, Maestría en Ciencias en Biodiversidad y Conservación de Ecosistemas Tropicales, Libramiento Norte Poniente, 1150, Lajas Maciel, 29039 Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Chiapas, Mexico

d Earlham College, Department of Biology, 801 National Road West, 47374 Richmond, Indiana, USA

e Red para la Conservación de los Anfibios y Reptiles de Yucatán, Km. 5.5 Carr. Sierra Papacal-Chuburná Pto. Tablaje, 31257 Sierra Papacal, Yucatán, Mexico

f Universidad Juárez Autónoma de Tabasco, División Académica de Ciencias Biológicas, Carretera Villahermosa-Cárdenas Km 0.5, 86039 Villahermosa, Tabasco, Mexico

g Universidad de Ciencias y Artes de Chiapas, Instituto de Ciencias Biológicas, Libramiento Norte Poniente, 1150, Lajas Maciel, 29039 Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Chiapas, Mexico

*Corresponding author: eduardo.reyes.grajales@gmail.com (E. Reyes-Grajales)

Abstract

Mexico has the second highest species richness of turtles in the world. However, there are several research gaps within this group compared to other reptiles, especially in the southeastern region, which has been described as the area with the highest herpetofaunal diversity. These data deficiencies have led to much uncertainty regarding the identification, occurrence, and status of the area’s turtles. Given this context, we provide an update for all the native turtle taxa present in each state in southeastern Mexico. We include maps with historical and unpublished distribution records for each taxon, along with a dichotomous key based on external morphology. We discuss the native turtle taxa documented in southeastern Mexico, the possible presence of some species in certain states, the identification of the turtles in this region, and their conservation status according to national, historical and current contexts.

Keywords: Conservation priorities; Freshwater turtles; Neotropical region; Reptiles; Testudines

Tortugas continentales del sureste de México: una actualización sobre la identificación, composición, distribución y conservación

Resumen

México tiene la segunda mayor riqueza de especies de tortugas en el mundo. Sin embargo, en este país existen varios vacíos de investigación dentro de este grupo en comparación con otros reptiles, especialmente en la región sureste, que ha sido descrita como el área con mayor diversidad herpetofaunística. Esta deficiencia de datos ha generado mucha incertidumbre en cuanto a la identificación, distribución y estado de las tortugas en la región. Dado este contexto, proporcionamos una actualización de todos los taxones nativos de tortugas presentes en cada estado del sureste de México. Incluimos mapas con registros históricos y no publicados de distribución para cada taxón, junto con una clave dicotómica basada en la morfología externa. Discutimos los taxones de tortugas nativas documentados en el sureste de México, la posible presencia de algunos taxones en ciertos estados, la identificación de las tortugas en esta región y su estado de conservación según los contextos nacional, histórico y actual.

Palabras clave: Prioridades de conservación; Tortugas dulceacuícolas; Región neotropical; Reptiles; Testudines

Introduction

The order Testudines includes 2 extant suborders, comprising 14 families, 97 genera, 7 marine turtle species, and 346 continental land and freshwater turtles (TTWG, 2021). Mexico supports the second richest turtle fauna per country in the world (after the USA) with 7 families, 13 genera, and 49 species of continental terrestrial and freshwater turtles (Hurtado-Gómez et al., 2024; Loc-Barragán et al., 2020; López-Luna et al., 2018; TTWG, 2021). When subspecies are included, a total of 63 distinct taxa are recognized in Mexico, with nearly half (49%, 31 taxa) being endemic (Hurtado-Gómez et al., 2024; Loc-Barragán et al., 2020; López-Luna et al., 2018; TTWG, 2021). Of those, 5 taxa have been described since 2010: Gopherus evgoodei, G. morafkai, Kinosternon cora, K. vogti, and Trachemys venusta iversoni (Edwards et al., 2016; Loc-Barragán et al., 2020; López-Luna et al., 2018; McCord et al., 2010; Murphy et al., 2011), and 5 taxa were taxonomically rearranged: K. cruentatum, K. mexicanum, K. stejnegeri, Terrapene mexicana, and T. yucatana (Hurtado-Gómez et al., 2024; Iverson & Berry, 2024; Martin et al., 2013; McCord, 2016;). It is noteworthy to mention that ~ 50% of Mexican continental turtles lack basic natural history data, which makes it cumbersome to comprehensively assess their actual conservation status (Flores-Villela & García-Vázquez, 2014; Macip-Ríos et al., 2015). Legler and Vogt (2013) stated that to solve “Mexican turtle conservation issues”, an integrative conservation research approach is necessary, to build knowledge about life history and ecology of these organisms.

Within Mexico, the southeastern region (Campeche, Chiapas, Oaxaca, Quintana Roo, Tabasco, Veracruz, and Yucatán) is characterized by high turtle endemism, with high presence of human induced alterations at different ecosystem levels (Ennen et al., 2020). Historically, many indigenous cultures in this region incorporated turtles (e.g., Dermatemys mawii, and those in the genera Trachemys and Kinosternon) into their diets as ceremonial or complementary foods (Beauregard et al., 2010; González-Porter et al., 2011; Legler & Vogt, 2013; Velázquez-Nucamendi et al., 2021). More recently, southeastern Mexico has become one of the hotspots where turtles are extracted for illegal trade worldwide, especially from Chiapas, Tabasco, and Veracruz (Legler & Vogt, 2013; Macip-Ríos et al., 2015; TTWG, 2021). In response to these actions, standards have been established at both the national level (e.g., the list of Mexican federal government protected species of flora and fauna) and international levels (e.g., the CITES appendices) to regulate the use of turtles. However, the application of protocols for the study or protection of this group of vertebrates in southeastern Mexico has shown inconsistencies in the processes of identification and/or systematization of information on their distribution (Flores-Villela & García-Vázquez, 2014; Legler & Vogt, 2013; Macip-Ríos et al., 2015). Therefore, there is a recognized need to design tools and update information on these aspects to safeguard these turtles.

To contribute to the resolution of this situation, in this study we set 2 main goals: 1) to provide an up-to-date checklist, with general comments on the distribution of the continental turtles occurring in southeastern Mexico, and 2) to present a practical dichotomous key for their identification that encompasses the current turtle taxonomy in southeastern Mexico. Our findings can be implemented immediately in activities related to the study and protection of continental turtles in this region of Mexico.

Materials and methods

We define southeastern Mexico as the states of Campeche, Chiapas, Oaxaca, Quintana Roo, Tabasco, Veracruz, and Yucatán (Fig. 1). The region is delimited by the Isthmus of Tehuantepec as the initial dividing line, given its significance as a major biogeographic barrier (Huidobro et al., 2006; Quiroz-Martínez et al., 2014). However, considering that several turtle taxa extend west and north just beyond this barrier, we chose to include Mexican states that comprise part of the isthmus region. This region comprises ~ 415,000 km2 originally vegetated with tropical evergreen forest and tropical deciduous forest with warm humid and warm subhumid climates (Leopold, 1950). In this region, turtles typically occur from sea level to approximately 1,200 m (Legler & Vogt, 2013). Major geographic features of the region are: the Gulf Coastal Plain, Sierra Madre de Oaxaca, Sierra Madre del Sur, Pacific Coastal Plain, Isthmus of Tehuantepec, Chiapas Highlands, Sierra Madre de Chiapas, Chiapas Coastal Plain, Central Depression of Chiapas, and the Yucatán Peninsula (Contreras-Balderas et al., 2008; Legler & Vogt, 2013). The main rivers are: Candelaria, Usumacinta, Grijalva, Tonalá, Coatzacoalcos, Papaloapan, Jamapa, Tehuantepec, and Ometepec (INEGI, 2021) (Fig. 1).

Georeferenced point locations were obtained for native continental turtles of southeastern Mexico from a combination of our own fieldwork records, the Turtle Taxonomy Working Group (TTWG, 2021, TTWG, 2025), and data repositories, including the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF, 2024), Sistema Nacional de Información sobre la Biodiversidad (SNIB-Conabio, 2024), Áreas Naturales y Vida Silvestre of the Secretaría del Medio Ambiente e Historia Natural (Semahn), iNaturalist (2024), and published scientific literature (Supplementary material: Table S1).

We used a systematic approach, establishing the TTWG shapefile (2021, 2025) as our base dataset. All newly identified occurrence points from additional sources were stored in a georeferenced database for the subsequent creation of maps using QGIS 3.34.2 (QGIS, 2024). Distribution polygons were based on TTWG (2025) and were expanded to include extralimital records verified through our compilation.

To ensure spatial accuracy, only points that provided open, non-obscured coordinates with reported location uncertainties of ≤ 10 km were incorporated. In the case of iNaturalist data, we exclusively used “research-grade” observations and excluded any records with obscured or low-precision coordinates (e.g., obscured within ~ 400 square miles). Records without supporting metadata or located significantly outside of known ranges were critically assessed, and when appropriate, excluded from analyses.

Special attention was given to isolated or potentially non-native records. For instance, we included K. flavescens from Veracruz based on the report of Auth et al. (2000) and the corroboration of voucher specimens (BCB 7489) by JBI at the Strecker Museum. We also carefully evaluated records of other species commonly subject to anthropogenic translocation, considering only those that plausibly represent native occurrences based on geographic and ecological context (see Discussion section). This rigorous validation process aimed to minimize the inclusion of records originating from village collections, pet trade, or other human-mediated movements, unless justified by the locality’s proximity to known native ranges or supporting documentation.

Our checklist includes valid names, authorities, and year of publication as in TTWG (2025). The dichotomous key we created based initially on the taxon descriptions provided in Legler and Vogt (2013). We then updated the key with the taxa recognized subsequent to Legler and Vogt (2013), and verified and added pertinent meristic and morphometric characters, and pigmentation patterns from specimens deposited in the Herpetology Section at the Zoológico Regional Miguel Álvarez del Toro (ZooMAT, Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Chiapas), the Colección herpetológica of El Colegio de la Frontera Sur (ECOSUR, San Cristóbal, Chiapas), and our own field data.

We refer to the plastral formula as the relative lengths of the midline sutures of each plastral scute (Supplementary material: Fig. S1). Due to inconsistencies (conventional vs. new) in the nomenclature of plastral scutes (Hutchison & Bramble, 1981; Legler & Vogt, 2013), we followed the recommendation of Legler and Vogt (2013) to use the numerical nomenclature for the plastral formula, where the counts start anteriorly (Supplementary material: Fig. S1). For the nomenclature of the head stripes, we followed Ernst (1978) for Rhinoclemmys spp., and Legler (1990) for Trachemys spp. We used the term “tomiodonts” according to Moldowan et al. (2015), and “tubercles” according to Winokur (1982).

For conservation criteria at the national level, we consulted the Mexican Government list in the NOM-059 (Semarnat, 2010, 2025), and for international criteria, we referred to the IUCN Red List of threatened species (IUCN, 2024) and the CITES appendices (CITES, 2024). Additionally, we used the EDGE metrics, as it prioritizes species based on their evolutionary distinctiveness (ED), which measures the relative contribution of a species to the total evolutionary history of their taxonomic group, and global endangerment (GE), or extinction risk (Gumbs et al., 2018). This metric has been recognized as useful to meaningful priorities for conservation.

Results

Native continental turtles in southeastern Mexico are represented by 5 families, 8 genera and 22 species with 9 recognized subspecies, for a total of 25 extant continental taxa (Table 1). The most speciose families in southeastern Mexico are the Kinosternidae, with a total of 13 taxa and Emydidae with 6 taxa (Table 1). The states with the greatest species richness are Oaxaca (16 taxa), followed by Chiapas (15), and Veracruz (13), and those with the least species richness were Quintana Roo (11), Tabasco (9) and Yucatán (7) (Table 2). Ten continental turtles in 4 genera are endemic to the region, as follows: Kinosternon (4 taxa), Terrapene (2 taxa), Trachemys (2 taxa) and Rhinoclemmys (2 taxa) (Table 3). The states with the highest number of Mexican endemic taxa are Oaxaca (2 species and 2 subspecies), Quintana Roo (2 species and 1 subspecies), Veracruz (2 species and 1 subspecies), and Yucatán (2 species and 1 subspecies) (Tables 1, 3).

Table 1

Diversity of continental turtles in southeastern Mexico. Ca = Campeche, Ch = Chiapas, Oa = Oaxaca, QR = Quintana Roo, Ta = Tabasco, Ve = Veracruz, Yu = Yucatán; CSP = count of states present; % S = percentage considering all the taxa distributed in southeastern Mexico; X = presence; – = undocumented.

| Family | Genus | Species | Subspecies | Ca | Ch | Oa | QR | Ta | Ve | Yu | CSP | % S |

| Chelydridae | Chelydra | C. rossignonii | X | X | X | – | – | X | – | 5 | 71.4 | |

| Dermatemydidae | Dermatemys | D. mawii | X | X | – | X | X | X | – | 5 | 71.4 | |

| Emydidae | Terrapene | T. mexicana | – | – | – | – | – | X | – | 1 | 14.3 | |

| T. yucatana | X | – | – | X | – | – | X | 3 | 42.9 | |||

| Trachemys | T. grayi | T. g. grayi | – | X | X | – | – | – | – | 2 | 28.6 | |

| T. venusta | T. v. cataspila | – | – | – | – | – | X | – | 1 | 14.3 | ||

| T. v. iversoni | – | – | – | X | – | – | X | 2 | 28.6 | |||

| T. v. venusta | X | X | X | X | X | X | – | 6 | 85.7 | |||

| Geoemydidae | Rhinoclemmys | R. areolata | R. areolata | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 7 | 100 |

| R. pulcherrima | R. p. incisa | – | X | X | – | – | – | – | 2 | 28.6 | ||

| R. p. pulcherrima | – | – | X | – | – | – | – | 1 | 14.3 | |||

| R. rubida | R. r. rubida | – | X | X | – | – | – | – | 2 | 28.6 | ||

| Kinosternidae | Claudius | C. angustatus | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 7 | 100 | |

| Kinosternon | K. abaxillare | – | X | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | 14.3 | ||

| K. acutum | X | X | X | X | X | X | – | 6 | 85.7 | |||

| K. creaseri | X | – | – | X | – | – | X | 3 | 42.9 | |||

| K. cruentatum | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 7 | 100 | |||

| K. flavescens | – | – | – | – | – | X | – | 1 | 14.3 | |||

| K. herrerai | – | – | – | – | – | X | – | 1 | 14.3 | |||

| K. integrum | – | – | X | – | – | – | – | 1 | 14.3 | |||

| K. leucostomum | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 7 | 100 | |||

| K. mexicanum | – | X | X | – | – | – | – | 2 | 28.6 | |||

| K. oaxacae | – | – | X | – | – | – | – | 1 | 14.3 | |||

| Staurotypus | S. salvinii | – | X | X | – | – | – | – | 2 | 28.6 | ||

| S. triporcatus | X | X | X | X | X | X | – | 6 | 85.7 | |||

| Totals by state | 11 | 15 | 16 | 11 | 9 | 13 | 7 |

Table 2

Summary of taxonomic diversity of continental turtles by state in southeastern Mexico. The number of continental turtles found in Mexico was established according to TTWG (2021, 2025). Hurtado-Gómez et al. (2024), and Iverson and Berry (2024). The percentage with respect to diversity at the national level (left) and in southeastern Mexico (right) is in parentheses.

| Place | Families | Genera | Species | Taxa |

| Mexico | 7 | 13 | 50 | 65 |

| Southeastern Mexico | 5 (71.4) | 8 (61.5) | 22 (45) | 25 (39.7) |

| Campeche | 5 (71.4 / 100) | 8 (61.5 / 100) | 11 (22.4 / 50) | 11 (17.5 / 44) |

| Chiapas | 5 (71.4 / 100) | 7 (53.8 / 87.5) | 15 (30.6 / 68.2) | 15 (23.8 / 60) |

| Oaxaca | 4 (57.1 / 80) | 6 (46.2 / 75) | 15 (30 / 68.2) | 16 (25.4 / 64) |

| Quintana Roo | 4 (57.1 / 80) | 6 (46.2 / 75) | 10 (20 / 45.5) | 11 (17.5 / 44) |

| Tabasco | 5 (71.4 / 100) | 7 (53.8 / 87.5) | 9 (18.4 / 40.9) | 9 (14.3 / 36) |

| Veracruz | 5 (71.4 / 100) | 8 (61.5 / 100) | 13 (26.5 / 59.1) | 14 (22.2 / 56) |

| Yucatán | 3 (42.9 / 60) | 4 (30.8 / 50) | 5 (10.2 / 22.7) | 5 (7.9 / 20) |

Dichotomous key to the general and plastron view of each turtle (Fig. 2), the plastral nomenclature and the names of the head stripes (Supplementary material: Figs. 1S, S2). The Spanish translation is presented in Supplementary material.

1A. Posterior plastral lobe ends in a point …………………………………… 2 (Fig. 2A)

1B. Posterior plastral lobe does not end in a point …………………………………… 5 (Fig. 2B)

2A. Reduced bridge almost the same length size as plastral scute 2. Kinosternidae: Staurotypus, …………………………………… 3

2B. Extremely narrow, reduced bridge shorter than the length of plastral scute 2 …………………………………… 4

3A. Top and sides of head boldly marked with irregular dark and pale reticulations; 3 distinctive carapace keels, well developed posteriorly, especially the middle keel ……………………………………S. triporcatus (Fig. 2Y)

3B. Top of head dark, usually unicolored, lacking bold pattern; 3 distinctive carapace keels of similar size, anterior to posterior ……………………………………S. salvinii (Fig. 2X)

4A. Three pointed tomiodonts on the upper tomium; neck not ornamented with cutaneous tubercles; tail not as long as the plastron …………………………………… Kinosternidae: Claudius angustatus (Fig. 2M)

4B. One medial pointed extension on the upper tomium; neck ornamented with long, flat, pointed cutaneous tubercles; tail about as long as the plastron …………………………………… Chelydridae: Chelydra rossignonii (Fig. 2A)

5A. Interdigital membranes not present on forefeet or hind feet …………………………………… 6

5B. Interdigital membranes present on fore and hind feet ……………………………………11

6A. One plastral hinge, allowing movement of anterior and posterior plastral lobes; the posterior end of the plastron rounded ……………………………………Emydidae: Terrapene, 7

6B. A transverse plastral hinge is absent; the posterior end of the plastron is notched …………………………………… Geoemydidae: Rhinoclemmys, 8

7A. Plastral scute 5 averaging 15% the straight-midline length of the posterior plastral lobe; plastral scute 3 averaging 23% the straight-midline length of the anterior plastral lobe ……………………………………T. mexicana (Fig. 2C)

7B. Plastral scute 5 averaging 21% the straight-midline length of the posterior plastral lobe; plastral scute 3 averaging 33% the straight-midline length of the anterior plastral lobe …………………………………… T. yucatana (Fig. 2D)

8A. Yellow markings predominate on the forefeet, hind feet, neck and/or head ……………………………………9

8B. Red markings predominate on the forefeet, hind feet, neck and/or head …………………………………… 10

9A. Red/orange dorsolateral head stripes continuous or discontinuous; each costal scute uniformly colored ……………………………………R. areolata (Fig. 2I)

9B. Red/orange dorsolateral head stripes are absent; each lateral scute with 1 pale areolar spot with a dark outline, possibly with obvious light-colored concentric rings around it ……………………………………R. rubida rubida (Fig. 2L)

10A. Carapace is elevated; inferior surface of each marginal scute with 1 transverse pale mark ……………………………………R. pulcherrima incisa (Fig. 2J)

10B. Carapace is depressed; inferior surface of each marginal scute with 2 transverse, dark-bordered pale marks ……………………………………R. p. pulcherrima (Fig. 2K)

Table 3

Conservation status of the continental turtles of southeastern Mexico. NOM-059 = List of Mexican federal government protected species of flora and fauna; P = endangered (in danger of extinction), Pr = under special protection, A = threatened; Red List = the IUCN Red list of threatened species; CITES = Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora; En = national endemism; Y = endemic to Mexico; N = not endemic to Mexico; EDGE = EDGE score (Gumbs et al., 2018; higher threat = higher score).

| Taxa | NOM-059 | Red List | CITES | EDGE | En |

| Chelydra rossignonii | Pr | Vulnerable A2d | – | 5.22 | N |

| Dermatemys mawii | P | Critically endangered A2abd+4d | II | 7.15 | N |

| Terrapene mexicana | Pr | Vulnerable A2bcde+4bcde | II | 4.19 | Y |

| Terrapene yucatana | Pr | Vulnerable A2bcde+4bcde | II | 4.19 | Y |

| Trachemys grayi grayi | – | – | – | – | N |

| Trachemys venusta cataspila | – | – | – | – | Y |

| Trachemys venusta iversoni | – | – | – | – | Y |

| Trachemys venusta venusta | – | – | – | – | N |

| Rhinoclemmys areolata | A | Near threatened | II | 3.77 | N |

| Rhinoclemmys pulcherrima incisa | A | – | II | – | N |

| Rhinoclemmys pulcherrima pulcherrima | A | – | II | – | Y |

| Rhinoclemmys rubida rubida | Pr | Near threatened | II | 3.87 | Y |

| Claudius angustatus | P | Near threatened | II | 4.36 | N |

| Kinosternon abaxillare | – | Vulnerable A2cd+4cd | II | – | N |

| Kinosternon acutum | Pr | Near threatened | II | 4.36 | N |

| Kinosternon creaseri | – | Least concern | II | 3.67 | Y |

| Kinosternon cruentatum | – | – | II | – | N |

| Kinosternon flavescens | – | Least concern | II | 3.67 | N |

| Kinosternon herrerai | Pr | Near threatened | II | 4.36 | Y |

| Kinosternon integrum | Pr | Least concern | II | 3.67 | Y |

| Kinosternon leucostomum | Pr | – | II | – | N |

| Kinosternon mexicanum | – | – | II | – | N |

| Kinosternon oaxacae | Pr | – | II | 4.36 | Y |

| Staurotypus salvinii | Pr | Near threatened | II | 4.69 | N |

| Staurotypus triporcatus | A | Near threatened | II | 4.69 | N |

| Total of taxa in the categories considered | 15 | 15 | 20 | 15 |

11A. There are no transversely oriented plastral hinges allowing plastral movement ……………………………………12

11B. There are 1 or 2 transversely oriented plastral hinges, allowing 1 or both plastral lobes to move around the scute 4…………………………………… Kinosternidae: Kinosternon, 16

12A. The head typically has a pale-colored patch that covers part or all of the dorsal region of the head but is never striped ……………………………………Dermatemydidae: Dermatemys mawii (Fig. 2B)

12B. The head is colored with obvious yellow stripes…………………………………… Emydidae: Trachemys, 13

13A. Carapace ocelli centered on each costal scute and occupying most of scute…………………………………… 14

13B. Carapace ocelli not centered on costal scutes ……………………………………15

14A. Carapace ocelli have an obvious large dark center to each ocellus ……………………………………T. venusta iversoni (Fig. 2G)

14B. Carapace ocelli lack an obvious dark center to each ocellus ……………………………………T. v. venusta (Fig. 2H)

15A. No light-colored ocelli on carapace; most of the central secondary orbitocervical stripes are narrow, of roughly equal width, and lacking black borders…………………………………… T. grayi grayi (Fig. 2E)

15B. Ocelli not centered in lateral scutes or broken; The postorbital stripe is thin where it contacts the orbit, then widens to about the diameter of the orbit; the central secondary orbitocervical stripes vary in width ……………………………………T. v. cataspila (Fig. 2F)

16A. Only the anterior plastral lobe is movable ……………………………………K. herrerai (Fig.2S)

16B. Both plastral lobes are movable relative to plastral scute 4 ……………………………………17

17A. Axillary scutes absent ……………………………………K. abaxillare (Fig. 2N)

17B. Axillary scutes present ……………………………………18 (see Fig. 2P)

18A. Moveable plastral lobes do not close the shell opening completely ……………………………………19

18B. Moveable plastral lobes close the shell opening completely ……………………………………20

19A. Plastral formula is 6 < = > 4 > 2 > 1 > 5 > 3 ……………………………………K. flavescens (Fig. 2R)

19B. Formula plastral is 4 > 6 > 1 > 5 > 2 > 3 ……………………………………K. oaxacae (Fig. 2W)

20A. Eyes with red pigment ……………………………………K. acutum (Fig. 2O)

20B. Eyes do not have red pigment…………………………………… 21

21A. Tricarinate carapace (less obvious in older individuals) ……………………………………22

21B. Unicarinate carapace ……………………………………23

22A. Plastral formula is 4 > 6 ……………………………………K. integrum (Fig. 2T)

22B. Plastral formula is 6 > 4 ……………………………………24

23A. Plastral formula is 1 > 2 ……………………………………K. creaseri (Fig. 2P)

23B. Plastral formula is 2 > 1 ……………………………………K. leucostomum (Fig. 2U)

24A. Maximum carapace width averages 77.1% (standard deviation [S.D.] 2.8%) of maximum plastron length in females and 74.6% (S.D. 2.8%) in males; the length of the plastral suture 4 averages 55.3% (S.D. 3.9%) of maximum shell height in females and 61.7% (S.D. 4.9%) in males ……………………………………K. mexicanum (Fig. 2V)

24B. Maximum carapace width averages 69.8% (S.D. 3.5%) of maximum plastron length in females and 68.9% (S.D. 2.8%) in males; the length of the plastral suture 4 averages 61.7% (S.D. 4.9%) of maximum shell height in females and 64.4% (S.D. 4.5%) in males ……………………………………K. cruentatum (Fig. 2Q)

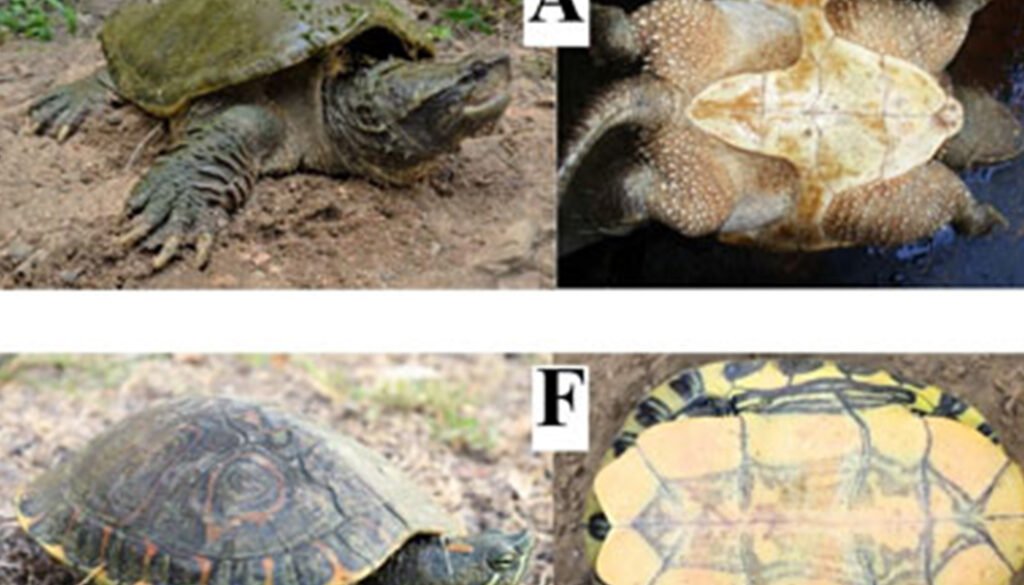

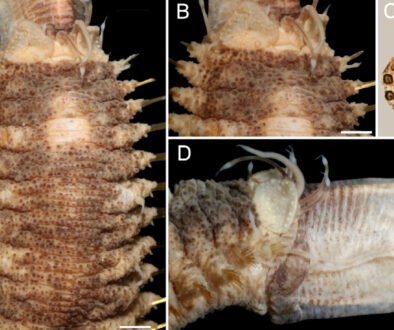

Figure 2. Photos of the continental turtles of southeastern Mexico. All photos (except when indicated, see Acknowledgments) by Eduardo Reyes-Grajales or John B. Iverson. A. Chelydra rossignonii, B. Dermatemys mawii, C. Terrapene mexicana, D. T. yucatana, E. Trachemys grayi grayi, F. T. venusta cataspila, G. T. v. iversoni, H. T. v. venusta, I. Rhinoclemmys areolata, J. R. pulcherrima incisa, K. R. p. pulcherrima, L. R. rubida rubida, M. Claudius angustatus, N. Kinosternon abaxillare, O. K. acutum, P. K. creaseri, Q. K. cruentatum, R. K. flavescens, S. K. herrerai, T. K. integrum, U. K. leucostomum, V. K. mexicanum, W. K. oaxacae, X. Staurotypus salvinii, Y. S. triporcatus.

Distributions of continental turtles of southeastern Mexico

In this section the abbreviations are: Ca = Campeche, Ch = Chiapas, Oa = Oaxaca, QR = Quintana Roo, Ta = Tabasco, Ve = Veracruz, Yu = Yucatán.

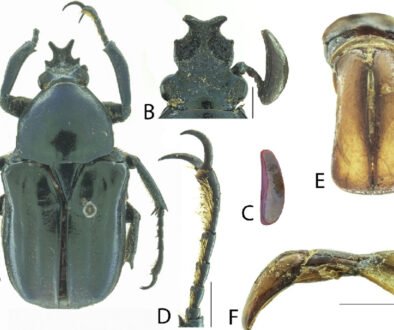

Chelydra rossignonii (Bocourt, 1868; Figs. 2A, 3A): along the Gulf of Mexico versant from the Jamapa River (Ve) to the Usumacinta River (Ta and Ch), including Laguna de Terminos (Ca). Other rivers include the Papaloapan, Coatzacoalcos (both in Oa and Ve), and lower Grijalva (Ch).

Dermatemys mawii Gray, 1847 (Figs. 2B, 3B): from the Jamapa River (Ve) to Champoton River (Ca) on the Gulf of Mexico versant, including the Usumacinta (Ca, Ch and Ta) and Lacantun Rivers (Ch). In Chetumal Bay (QR) the distribution extends to and beyond the Belize border.

Terrapene mexicana (Gray, 1849; Figs. 2C, 3C): from the Tamesi River to the Jamapa River, including the Tamiahua Lake area; on the Gulf of Mexico versant in Veracruz and northward into Tamaulipas.

Terrapene yucatana (Boulenger, 1895; Figs. 2D, 3C): most of the western Yucatán Peninsula (primarily Yucatán and Campeche), with rare and localized occurrences in the northern region of Quintana Roo.

Trachemys grayi grayi (Bocourt, 1868; Figs. 2E, 3D): from La Arena River (Oa) to the Suchiate River on the Pacific versant (Ch), and southward to El Salvador.

Trachemys venusta cataspila (Günther, 1885; Figs. 2F, 3D): from the Jamapa River to the Panuco River (both in Ve) on the Gulf of Mexico versant, and northward in Tamaulipas.

Trachemys venusta iversoni McCord, Joseph-Ouni, Hagen, and Blanck, 2010 (Figs. 2G, 3D): most of the northern portions of Yucatán and Quintana Roo.

Trachemys venusta venusta (Gray, 1856; Figs. 2H, 3D): from the Jamapa River (Ve) to the Champoton River (Ca) on the Gulf of Mexico versant, including the Usumacinta (Ca, Ch and Ta) and Lacantun Rivers (Ch). In Chetumal Bay (QR) the distribution continues across the border into Belize and Guatemala.

Rhinoclemmys areolata (Duméril and Bibron in Duméril and Duméril, 1851; Figs. 2I, 3E): from the Jamapa River eastward (Ve) on the Gulf of Mexico versant throughout the north portions of Oaxaca and Chiapas and extended across Tabasco and the Yucatán peninsula (Ca, Yu and QR), and into Guatemala and Belize.

Rhinoclemmys pulcherrima incisa (Bocourt, 1868; Figs. 2J, 3F): from the west portion of the Copalita River (Oa) to the Suchiate River (Ch) on the Pacific versant, and southeast to Nicaragua.

Rhinoclemmys pulcherrima pulcherrima (Gray, 1856; Figs. 2K, 3F): from the Tehuantepec River (Oa) westward on the Pacific versant to the Balsas River, Guerrero.

Rhinoclemmys rubida rubida (Cope, 1870; Figs. 2L, 3E): from the Ometepec River (Oa) to the Suchiate River (Ch) on the Pacific versant, including the Atoyac and Tehuantepec basins (both in Oa).

Claudius angustatus Cope, 1865 (Figs. 2M, 3G): from the Jamapa River (Ve) to the western and southern Yucatán peninsula on the Gulf of Mexico versant, including the Usumacinta (Ca, Ch and Ta) and Lacantun Rivers (Ch), and southward into Guatemala and Belize.

Kinosternon abaxillare Baur in Stejneger, 1925 (Figs. 2N, 3H): restricted to the Grijalva River basin in the Central Depression and Plateau of Chiapas.

Kinosternon acutum Gray, 1831 (Figs. 2O, 3H): from the Jamapa River (Ve) to the Champoton River (Ca) on the Gulf of Mexico versant, including the Papaloapan, Coatzacoalcos (both in Oa and Ve) and lower Grijalva Rivers (Ch), and Laguna de Terminos (Ca). Also found on the southern Yucatán peninsula (Ca and QR), northern Guatemala and Belize.

Kinosternon creaseri Hartweg, 1934 (Figs. 2P, 3H): from the Champoton River (Ca) across the Yucatán peninsula (QR and Yu).

Kinosternon cruentatum Duméril and Bibron in Duméril and Duméril, 1851 (Figs. 2Q, 3I): from the Pánuco River (Ve) across the Tabasco lowlands to the entire Yucatán Peninsula on the Gulf of Mexico versant and into Guatemala and Belize.

Kinosternon flavescens Agassiz, 1857 (Figs. 2R, 3J): in southeastern Mexico it is restricted to the Panuco River basin (Ve) but ranges north across the Great Plains of the USA.

Kinosternon herrerai Stejneger, 1925 (Figs. 2S, 3K): from the Jamapa to the Panuco River (both in Ve) and northward on the Gulf of Mexico versant.

Kinosternon integrum Le Conte, 1854 (Figs. 2T, 3J): in southern Mexico from the Atoyac (Oa and Ve) and Tlapaneco River basins westward (Oa).

Kinosternon leucostomum Duméril and Bibron in Duméril and Duméril, 1851 (Figs. 2U, 3K): from the Jamapa River (Ve) to the Champoton River (Ca) on the Gulf of Mexico versant, including the Usumacinta (Ca, Ch and Ta) and Lacantun rivers (Ch). Also found from Chetumal Bay through eastern Quintana Roo, and southward through Central America.

Kinosternon mexicanum Le Conte, 1854 (Figs. 2V, 3J): restricted to the Pacific versant from the Tehuantepec River (Oa) to the Suchiate River (Ch), and southeast to El Salvador.

Kinosternon oaxacae Berry and Iverson, 1980 (Figs. 2W, 3J): restricted to the Ometepec, La Arena, Colotepec and Copalita River basins on the Pacific versant in Oaxaca; also, westward into Guerrero.

Figure 3. Distribution maps of the continental turtles of southern Mexico. The shaded color represents the distribution of each taxon (taken from TTWG, 2025). Maps with 2 or more taxa present dots and shade ranges with similar colors, and maps with a single taxa dots and shade ranges are orange. A. Chelydra rossignonii, B. Dermatemys mawii, C. Terrapene mexicana (orange), T. yucatana (red), D. Trachemys grayi grayi (orange), T. venusta cataspila (red), T. v. iversoni (green), T. v. venusta (purple), E. Rhinoclemmys areolata (orange), R. rubida rubida (red), F. R. pulcherrima incisa (orange), R. p. pulcherrima (red), G. Claudius angustatus, H. Kinosternon abaxillare (orange), K. acutum (red), K. creaseri (green), I. K. cruentatum (orange), J. K. flavescens (orange), K. integrum (red), K. mexicanum (green), K. oaxacae (purple) K. K. herrerai (red), K. leucostomum (orange), L. Staurotypus salvinii (orange), S. triporcatus (red). Maps by Eduardo Reyes-Grajales.

Staurotypus salvinii Gray, 1864 (Figs. 2X, 3L): from the Copalita River (Oa) to the Suchiate River (Ch) on the Pacific versant, and southeast to El Salvador.

Staurotypus triporcatus (Wiegmann, 1828; Figs. 2Y, 3L): from the Jamapa River (Ve) to Campeche state on the Gulf of Mexico versant, including the Usumacinta (Ca, Ch and Ta) and Lacantun River (Ch). Also, in southern Quintana Roo to Chetumal Bay and into Guatemala, Belize and northwestern Honduras. Insertar fig 3:12cm

There was a wide range of conservation status for most of the native turtle taxa under national and international criteria. For example, the Mexican Government list (NOM-059 list; Semarnat, 2010) includes 16 species (64% of all turtle taxa found in southeastern Mexico), the IUCN Red List includes 18 (72%), and 20 are CITES listed (80%; Table 3). The turtles listed by NOM-059 and IUCN Red List as most threatened are D. mawii, C. angustatus, and those within the genus Terrapene (Table 3). However, the taxa whose conservation status is totally unknown includes all species in the genus Trachemys (Table 3). The average EDGE score for southeastern Mexican turtle taxa was 4.41 with a minimum value of 3.67 (K. creaseri, K. flavescens, and K. integrum), and a maximum of 7.15 (D. mawii) (Table 3).

Discussion

This is the first dichotomous key based on external characteristics to consider all native continental turtles that are distributed in southeastern Mexico, in accordance with advances in turtle taxonomy. Other dichotomous keys, although effective, are based on the review of internal characteristics that require the sacrifice of the organisms —e.g., for cranial measurements (Legler & Vogt, 2013). These criteria may not be useful when carrying out population ecology studies, or when required in forensic procedures, as for the identification of confiscated turtles. The inclusion of a Spanish translation may facilitate the work of early-career professionals and local authorities in the preparation of expert reports on seized specimens, contributing to a more accurate assessment of the extent of illegal trade affecting certain taxa. Generally, when there are national reports of seizures involving mud turtles, this is limited to filing a report at the genus level (Profepa, 2020).

According to our results, southeastern Mexico supports 3/4 of the families —and more than half of the genera— found nationwide in Mexico (Table 2). These findings highlight southeastern Mexico as a region of high importance for the composition of land and freshwater turtles at the national level. This fact is consistent with studies focused on analyzing the composition of the Mexican herpetofauna (Flores-Villela & García-Vazquez, 2014; Johnson et al., 2017; Ramírez-Bautista et al., 2023). In addition to this, Oaxaca, Chiapas, and Veracruz stand out as the states with the highest species richness and/or endemism, respectively. These 3 states are located within the region considered the richest in total herpetofauna, a result of complex orography, diverse habitats and environments, and the biogeographic history of Mexico (Ramírez-Bautista et al., 2023).

Previously published checklists of reptile diversity in Mexico often included taxonomic and distributional inconsistencies for turtles, possibly due to the disposition of the taxonomic status at that time (e.g., Flores-Villela & García-Vazquez, 2014; Hernández-Ordoñez et al., 2015; Johnson et al., 2015; Wilson et al., 2013). For example, Johnson et al. (2015) reported the presence of T. ornata in Chiapas, but according to the TTWG (2021, 2025) this species occurs only in western Mexico, from Culiacan, Sinaloa to Puerto Vallarta, Jalisco. Likewise, R. areolata and C. serpentina have been reported from the southeastern part of the Lacandona rainforest, Chiapas (Hernández-Ordoñez et al., 2015). However, experts agree that there is no evidence for native populations of R. areolata in that region (TTWG, 2021, 2025). Velázquez-Nucamendi et al. (2021) suggested that the records might involve animals transported from Tabasco to this region of Chiapas. Furthermore, the closely related C. serpentina and C. rossignonii are commonly confused in southeastern Mexico, despite the former species being found only in the United States and Canada (TTWG, 2021, 2025).

It is important to note that the Berlandier’s tortoise (Testudinidae: Gopherus berlandieri) has been reported from the northern portion of Veracruz in recent checklists (Torres-Hernández et al., 2021; Vásquez-Cruz et al., 2021) and in virtual repositories (GBIF, 2024; iNaturalist, 2024; SNIB-Conabio, 2024). However, the inclusion of this turtle in these reports is not confirmed by collection data, and in the case of virtual repositories, it is based on individuals in captivity near the state border with Tamaulipas, where G. berlandieri is known to occur naturally. As no wild populations have been reported, and no wild individuals have been formally collected in the northern portion of Veracruz, we do not consider this species native to Veracruz. However, this issue needs to be addressed in the future to clarify the total richness of continental turtles in southeastern Mexico.

Southeastern Mexico has been categorized globally as an area with high to moderate endemism (Ennen et al., 2020). Our data indicates that this region contains 33% of the endemic continental turtle taxa at the national level within the genera Terrapene, Trachemys, Rhinoclemmys, and Kinosternon (Table 3). However, there are suggestions that in this region the probability remains high for potential new taxonomic discoveries or upgrades from subspecies to species, especially within Trachemys and Kinosternon, 2 genera that have been poorly studied in Mexico (Flores-Villela & García-Vázquez, 2014; Legler & Vogt, 2013). The T. venusta complex has historically presented many inconsistencies in its taxonomic relationships. Despite prominent color pattern differences among species, genetic divergences within this complex are shallow, and the taxonomic diversity of each species with several currently recognized subspecies could be overestimated (Fritz et al., 2011, 2023; Parham et al., 2013; Seidel & Ernst, 2017). Another scientific priority is to clarify the genetically distinct group of D. mawii located in the Papaloapan River in Veracruz (González-Porter et al., 2011), and into the Lacandona rainforest (Martínez Gómez et al., 2017).

Historically, turtles in southeastern Mexico have been widely exploited at unsustainable rates, resulting in negative repercussions on their populations and pushing some species to the brink of near local extinctions (Legler & Vogt, 2013). Examples include C. angustatus and D. mawii, both recognized as most threatened by national criteria (Table 3). For the first species, in a study conducted in Lerdo de Tejada, Veracruz (Mexico), Espejel-González (2004) reported a capture of 254 individuals. However, due to the high rates of extraction per year (Espejel-González, 2004), Reynoso et al. (2016) found no individuals in the same locality. For D. mawii in the Lacandona rainforest (Chiapas), a systematic evaluation that started in the 1980s and concluded 20 years later inferred a reduction of ~ 80% of the native population in the area (Guichard-Romero, 2006; Legler & Vogt, 2013). Other current events that provide a glimpse of the crisis facing Mexican turtles include 2 trade confiscations in 2020. In just 2 seizures, approximately 30,000 Mexican turtles were confiscated, mainly Trachemys, Kinosternon, Claudius, and Staurotypus (Profepa, 2020; Excelsior, 2020).

We found that D. mawii, T. mexicana, and T. yucatana were the only species in which their risk categories were consistent under national and international criteria. For the remainder of the turtles distributed in southeastern Mexico, these categorizations were inconsistent or nonexistent (Table 3). The genus Trachemys is the one that is not under any national or international protection criteria (Table 3). The absence of protection criteria does not indicate a lesser concern for the conservation of these turtles, but rather a potential neglect of an approach to diagnose the conservation status through their distribution, even though these turtles are highly demanded for local consumption and the illegal pet trade (Beauregard-Solís et al., 2010; Profepa, 2020; Velázquez-Nucamendi et al., 2021). One main problem for the conservation of turtles in Mexico is the lack of concordance between the lists issued by the national Government and those by international organizations (Macip-Ríos et al., 2015). This leads to confusion by the Mexican public administration regarding the data available for decisions related to management and permitting, especially for species poor studied and highly demanded as Trachemys and Kinosternon (Macip-Ríos et al., 2015; Profepa, 2020).

Mexico is an active country in the trade of wild species. Just in the period 2007-2011, Mexico was the second-largest exporter worldwide, with approximately 750,000 specimens of live reptiles removed, of which continental turtles stood out (Semarnat, 2012). Therefore, agreement between national and international standards is a high priority to conserve Mexican turtle species. More research and data are needed on least Rhinoclemmys, K. cruentatum, K. herrerai, K. leucostomum, K. oaxacae, K. mexicanum, and S. salvinii. The need for updates in national and international legal regulations is recognized as essential to the protection of the different species of turtles that are distributed in southeastern Mexico. We encourage the assessment of population trends and potential threats to provide a more comprehensive conservation status for these turtles under national and international criteria.

The information provided in this work should help to improve and focus future research and conservation in southeastern Mexico. However, we recognize that more information is required on the population status of the turtles in each state to face the new challenges that we need to consider for their conservation. Indeed, addressing the remaining gaps in the distribution and systematics of certain turtle species would be a valuable avenue for future research. Continued efforts to enhance our understanding of these aspects will contribute to more accurate assessments of conservation status. Finally, we encourage the resolution of the discrepancies between international and Mexican conservation priorities to ensure the protection of the turtles that occur in this region. Aligning priorities will help create more unified and impactful strategies, ensuring better protection for these turtles and their habitats (Macip-Ríos et al., 2015). This underscores the importance of international collaboration and coordination to address conservation challenges comprehensively.

Acknowledgments

Fieldwork was conducted under the Mexican Federal Government permit numbers: SGPA/DGVS/01156/19 and SGPA/DGVS/06570/21 issued by Semarnat. We thank the authorities of the Áreas Naturales y Vida Silvestre from SEMAHN for providing essential information on turtle locations; Carlos A. Guichard Romero and Antonio Ramirez for providing access to the ZooMAT facilities; Antonio Muñoz Alonso for providing access to the reptile collection from ECOSUR, and Anders G. J. Rhodin for providing all Mexican turtle localities from the Turtle Taxonomy Working Group’s distributional database (TTWG 2021, 2025). For photographs in Fig. 2, we thank Ernesto Eduardo Perera Trejo (A, general view and plastron), Julio Gonzalez (C, plastron), Mike Jones (D and P, general view and plastron), Taggert Butterfield (L plastron), Alejandra Monsivais (K general view and plastron), Antonio Ramírez (M, general view), and Erasmo Cázares (S, general view and plastron). Anders G. J. Rhodin, Peter Paul van Dijk, Oscar Flores-Villela, Taggert Butterfield, Jacobo Reyes-Velasco and Donald McKnight made important comments to improve this manuscript. We thank the Turtle Survival Alliance, Mohamed bin Zayed Species Conservation Fund (242536595), Turtle Conservation Fund, Chelonian Research Foundation (TCF-0790), and Turtle Taxonomy Fund for their support during field work and laboratory analysis. Finally, ERG is grateful to the scholarship “Becas de Preparación de Posgrado” from El Colegio de la Frontera Sur for support during the writing of this work.

References

Auth, D. L., Smith, H. M., Brown, B. C., & Lintz, D. (2000). A description of the Mexican amphibian and reptile collection of the Strecker Museum. Bulletin of the Chicago Herpetological Society, 35, 65–85.

Barão-Nóbrega, J. A. L., Nahuat-Cervera, P. E., Avella, I., Capehart, G., Garcia, B., Oakley, J. et al. (2022). Herpetological diversity in Calakmul, Campeche, Mexico: species list with new distribution notes. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 93, e933927. https://doi.org/10.22201/ib.20078706e.2022.93.3927

Barragán-Vázquez, M. D. R., Ríos-Rodas, L., Fucsko, L. A., Mata-Silva, V., Porras, L. W., Rocha, A. et al. (2022). The herpetofauna of Tabasco, Mexico: composition, distribution, and conservation status. Amphibian and Reptile Conservation, 16, 1–61.

Beauregard-Solís, G., Zenteno-Ruiz, C., Armijo-Torres, R., & Guzmán-Juárez, E. (2010). Las tortugas de agua dulce: patrimonio zoológico y cultural de Tabasco. Kuxulkab´, 17, 5–19.

Calderón, R., Cedeño-Vázquez, J. R., & Pozo, C. (2003). New distributional records for amphibians and reptiles from Campeche, Mexico. Herpetological Review, 34, 269–272.

Casas-Andreu, G., Méndez-De la Cruz, F. R., & Camarillo, J. L. (1996). Anfibios y reptiles de Oaxaca. Lista, distribución y conservación. Acta Zoológica Mexicana, 69, 1–35. https://doi.org/10.21829/azm.1996.69691928

Cázares-Hernández, E. (2015). Guía de las tortugas dulceacuícolas de Veracruz. Zongolica, Veracruz: Instituto Tecnológico Superior de Zongolica.

Charruau, P., Morales-Garduza, M. A., López-Luna, M. A., Reyes-

Trinidad, J. G., Ramírez-Pérez, M. A., López-Hernández, J. A. et al. (2023). Herpetofauna de los humedales de la laguna de Chaschoc, Tabasco, México. Revista Latinoamericana de Herpetología, 6, 75–92. https://doi.org/10.22201/fc.25942158e.2023.2.616

Chrapliwy, P. S. (1956). Extensions of known range of certain amphibians and reptiles of Mexico. Herpetologica, 12, 121–124.

CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora). (2024). The CITES Appendices, 2024. Retrieved April 7, 2023, from: https://cites.org/eng

Conabio (Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad). (2024). Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad. Retrieved April 7, 2024, from: https://www.gob.mx/conabio

Contreras-Balderas, S., Ruiz-Campos, G., Schmitter-Soto, J. J., Díaz-Pardo, E., Contreras-Macbeath, T., Medina-Soto, M. et al. (2008). Freshwater fishes and water status in México: a country-wide appraisal. Aquatic Ecosystem Health and Management, 11, 246–256.

Díaz-Gamboa, L., May-Herrera, D., Gallardo-Torres, A., Cedeño-Vázquez, R., González-Sánchez, V., Chiappa-Carrara, X. et al. (2020). Catálogo de reptiles de la península de Yucatán. Mérida, Yucatán: Escuela Nacional de Estudios Superiores Unidad Mérida, UNAM.

Edwards, T., Karl, A. E., Vaughn, M., Rosen, P. C., Torres, C. M., & Murphy, R.W. (2016). The Desert Tortoise trichotomy: Mexico hosts a third, new sister-species of tortoise in the Gopherus morafkai–G. agassizii group. Zookeys, 562, 131–158. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.562.6124

Ennen, J. R., Agha, M., Sweat, S. C., Matamoros, W. A., Lovich, J. E., Rhodin, A. G. J. et al. (2020). Turtle biogeography: global regionalization and conservation priorities. Biological Conservation, 241, 108323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2019.108323

Ernst, C. H. (1978). A revision of the Neotropical turtle genus Callopsis (Testudines: Emydidae: Batagurinae). Herpetologica, 34, 113–134.

Espejel-González, V. E. (2004). Aspectos biológicos del manejo del chopontil, Claudius angustatus (Testudines: Staurotypinae) (M. Sc. Thesis). Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Xalapa, Veracruz.

EXCELSIOR. (2020). Estos son los animales rescatados tras decomiso histórico en Iztapalapa. Retrieved April 7, 2023, from: https://www.excelsior.com.mx/comunidad/estos-son-los-animales-rescatados-tras-decomiso-historico-en-iztapa

lapa/1419311

Ferreira-García, M. E., & Canseco-Márquez, L. (2006). Estudio de la herpetofauna del Monumento Natural Yaxchilán, Chiapas, México. In A. Ramírez-Bautista, L. Canseco-Máquez, & F. Mendoza-Quijano (Eds.), Inventarios herpetofaunísticos de México: avances en el conocimiento de su biodiversidad (pp. 293–310). México D.F.: Sociedad Herpetológica Mexicana, A.C.

Flores-Villela, O., & García-Vázquez, U. O. (2014). Biodiversidad de reptiles en México. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 85 (Suplem.), S467–S475. https://doi.org/10.7550/rmb.43236

Fritz, U., Kehlmaier, C., Scott, R. J., Fournier, R., McCranie, J. R., & Gallego-García, N. (2023). Central American Trachemys revisited: new sampling questions current understanding of taxonomy and distribution (Testudines: Emydidae). Vertebrate Zoology, 73, 513–523. https://doi.org/10.3897/vz.73.e104438

Fritz, U., Stuckas, H., Vargas-Ramírez, M., Hundsdöfer, A. K., Maran, J., & Päckert, M. (2011). Molecular phylogeny of Central and South American slider turtles: implications for biogeography and systematics (Testudines: Emydidae: Trachemys). Journal of Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Research, 50, 125–136. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0469.2011.00647.x

GBIF (Global Biodiversity Information Facility). (2024). Retrieved April 7, 2023, from: https://www.gbif.org/

González-Porter, G. P., Hailer, F., Flores-Villela, O., García-Anleu, R., & Maldonado, J. E. (2011). Patterns of genetic diversity in the critically endangered Central American river turtle: human influence since the Mayan age? Conservation Genetics, 12, 1229–1242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10592-011-0225-x

González-Sánchez, V. H., Johnson, J. D., García-Padilla, E., Mata-Silva, V., DeSantis, D. L., & Wilson. L.D. (2017). The herpetofauna of the Mexican Yucatán Peninsula: composition, distribution, and conservation. Mesoamerican Herpetology, 4, 264–380.

Guichard-Romero, C. A. (2006). Situación actual de las poblaciones de tortuga blanca (Dermatemys mawii) en el sureste de México (Informe final del Proyecto AS003-Conabio). Mexico City: Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad.

Gumbs, R., Gray, C. L., Wearn, O. R., & Owen, N. R. (2018). Tetrapods on the EDGE: Overcoming data limitations to identify phylogenetic conservation priorities. Plos One, 13, e0194680. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0194680

Hernández-Ordoñez, O., Arroyo-Rodríguez, V., González-Hernández, A., Russildi, G., Luna-Reyes, R., Martínez-Ramos, M. et al. (2015). Extensión del área de distribución de anfibios y reptiles en la parte sureste de la selva Lacandona, México. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 86, 457–468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmb.2015.04.005

Hernández-Ordóñez, O., Martínez-Ramos, M., Arroyo-Rodríguez, V., González-Hernández, A., González-Zamora, A., Zárate, D. A. et al. (2014). Distribution and conservation status of amphibian and reptile species in the Lacandona rainforest, Mexico: an update after 20 years of research. Tropical Conservation Science, 7, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F194008291400700101

Huidobro, L., Morrone, J. J., Villalobos, J. L., & Álvarez, F. (2006). Distributional patterns of freshwater taxa (fishes, crustaceans, and plants) from the Mexican transition zone. Journal of Biogeography, 33, 731–741. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2005.01400.x

Hurtado-Gómez, J. P., Vargas-Ramírez, M., Iverson, J. B., Joyce, W., Mccranie, J. R., & Fritz, U. 2024. Diversity and biogeography of South American Mud Turtles elucidated by multilocus DNA sequencing (Testudines: Kinosternidae). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 197, 108083. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2024.108083

Hutchison, J. H., & Bramble, D. M. (1981). Homology of the plastral scales of the Kinosternidae and related turtles. Herpetologica, 37, 73–85.

iNaturalist. (2024). iNaturalist. Retrieved June 6, 2024, from: https://www.inaturalist.org/

IUCN (International Union for the Conservation of Nature). 2024. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved June 6, 2024, from: http://www.iucnredlist.org

INEGI (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía). (2021). Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. Retrieved March 3, 2021: https://www.inegi.org.mx/

Iverson, J. B., & Berry, J. F. (2024). Morphometric variation in the Red-cheeked Mud Turtle (Kinosternon cruentatum) and its taxonomic significance. Chelonian Conservation and Biology, 23, 13–22. https://doi.org/10.2744/CCB-1589.1

Iverson, J. B., Le, M., & Ingram, C. (2013). Molecular phylogenetics of the mud and musk turtle family Kinos-

ternidae. Mollecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 69, 929–939. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2013.06.011

Johnson, J. D., Mata-Silva, V., García-Padilla, E., & Wilson, L. D. (2015). The herpetofauna of Chiapas, Mexico: compo-

sition, distribution, and conservation. Mesoamerican Herpetology, 2, 272–329.

Johnson, J. D., Wilson, L. D., Mata-Silva, V., García-Padilla, E., & DeSantis, D. L. (2017). The endemic herpetofauna of Mexico: organisms of global significance in severe peril. Mesoamerican Herpetology, 4, 544–620.

Lee, J. C. (1996). The amphibians and reptiles of the Yucatán Peninsula. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Legler, J. M. (1990). The genus Pseudemys in Mesoamerica: taxonomy, distribution, and origins. In J. W. Gibbons (Ed.), Life history and ecology of the slider turtle (pp. 82–105). Washington D.C: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Legler, J. M., & Vogt, R. C. (2013). The turtles of Mexico: land and freshwater forms. Berkeley, California: University of California Press.

Leopold, A. S. (1950). Vegetation zones of Mexico. Ecology, 31, 507–518.

Loc-Barragán, J. A., Reyes-Velasco, J., Woolrich-Piña, G. A., Grünwald, C. T., Venegas-de Anaya, M., Rangel-Mendoza, J. et al. (2020). A new species of mud turtle of genus Kinosternon (Testudines: Kinosternidae) from the Pacific coastal plain of northwestern Mexico. Zootaxa, 4885, 509–529. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4885.4.3

López-Luna, M. A., Cupul-Magaña, F. G., Escobedo-Galván, A. H., Gonzáles-Hernández, A. J., Centenero-Alcalá, E., Rangel-Mendoza, J. A. et al. (2018). A distinctive new species of mud turtle from western Mexico. Chelonian Conservation and Biology, 17, 2–13. https://doi.org/10.2744/CCB-1292.1

Luna-Reyes, R., Canseco-Márquez, L., & Hernández-García, E. (2013). Los reptiles. In A. Cruz-Angón, E. D. Melgarejo, F. Camacho-Rico y K. C. Nájera-Cordero (Ed.), La biodiversidad en Chiapas, Estudio de Estado (pp.319–328). México D.F.: Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad/ Gobierno del Estado de Chiapas.

Macip-Ríos, R., Ontiveros, R., López-Alcaide, S., & Casas-Andreu, G. (2015). The conservation status of the freshwater and terrestrial turtles of Mexico: A critical review of biodiversity conservation strategies. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 86, 1048–1057. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmb.2015.09.013

Martin, B. T., Bernstein, N. P., Birkhead, R. D., Koukl, J. F., Mussmann, S. M., & Placyk, J. S. (2013). Sequence-based molecular phylogenetics and phylogeography of the American box turtles (Terrapene spp.) with support from DNA barcoding. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 68, 119–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2013.03.006

Martínez-Gómez, J. (2017). Sistemática molecular e historia evolutiva de la Familia Dermatemydidae en Mesoamérica (Bachelor Thesis). Universidad de Ciencias y Artes de Chiapas. Chiapas, México.

Mata-Silva, V., García-Padilla, E. L., Rocha, A., Desantis, D. L., Johnson, J. D., Ramírez-Bautista, A. et al. (2021). A reexamination of the herpetofauna of Oaxaca, Mexico: composition update, physiographic distribution, and conservation commentary. Zootaxa, 4996, 201–252. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4996.2.1

Mata-Silva, V., Johnson, J. D., Wilson, L. D., & García-Padilla, E. (2015). The herpetofauna of Oaxaca, Mexico: composition, physiographic distribution, and conservation status. Mesoamerican Herpetology, 2, 6–62.

McCord, W. P., Joseph-Ouni, M., Hagen, C., & Blanck, T. (2010). Three new subspecies of Trachemys venusta (Testudines: Emydidae) from Honduras, northern Yucatán (Mexico), and Pacific coastal Panama. Reptilia, 71, 39–49.

McCord, R. D. (2016). What is Kinosternon arizonense? Historical Biology, 28, 310–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2015.1053879

Moldowan, P. D., Brooks, R. J., & Litzgus, J. D. (2015). Turtles with “teeth”: beak morphology of Testudines with a focus on the tomiodonts of Painted Turtles (Chrysemys spp.). Zoomorphology, 35, 121–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00435-015-0288-1

Moreno-Avendaño, V., & Reyes-Grajales, E. (2022). Distribution. Central Chiapas Mud Turtle. Kinosternon abaxillare. Herpetological Review, 53, 261.

Murphy, R. W., Berry, K. H., Edwards, T., Leviton, A. E., Lathrop, A., & Riedle, J. D. (2011). The dazed and confused identity of Agassiz’s land tortoise, Gopherus agassizii (Testudines, Testudinidae) with the description of a new species, and its consequences for conservation. Zookeys, 113, 39–71. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.113.1353

Muñoz-Alonso, L. A., Rodiles-Hernández, R., López-León, N. P., González-Navarro, A., Chau-Cortés, A. M., & Nieblas-Camacho, J. A. (2018). Diversidad de la herpetofauna en la cuenca del Usumacinta, México. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 89 (Suplem.), 79–99. https://doi.org/10.22201/ib.20078706e.2018.0.2447

Ortiz-Medina, J. A., Cabrera-Cen, D. I., Nahuat-Cervera, P. E., & Chablé-Santos, J. B. (2020). New distributional records for the herpetofauna of Campeche and Yucatán, Mexico. Herpetological Review, 51, 83–87.

Parham, J. F., Papenfuss, T. J., van Dijk, P. P., Wilson, B. S., Marte, C., Rodríguez-Schettino, L. et al. (2013). Genetic introgression and hybridization in Antillean freshwater turtles (Trachemys) revealed by coalescent analyses of mitochondrial and cloned nuclear markers. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 67, 176–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2013.01.004

Profepa (Procuraduría Federal de Protección al Ambiente). 2020. Profepa asegura precautoriamente más de 15 mil tortugas que pretendían exportarse de manera ilegal a China. Retrieved March 3, 2021: https://www.gob.mx/profepa/prensa/profepa-asegura-precautoriamente-mas-de-15-mil-tortugas-que-pretendian-exportarse-de-manera-ilegal-a-china?idiom=es

Quiroz-Martínez, B., Álvarez, F., Espinosa, H., & Salgado-Maldonado, G. (2014). Concordant biogeographic patterns among multiple taxonomic groups in the Mexican freshwater biota. Plos one, 9, e105510. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0105510

Ramírez-Bautista, A., Torres-Hernández, L. A., Cruz-Elizalde, R., Berriozábal-Islas, C., Hernández-Salinas, U., Wilson, L. D. et al. (2023). An updated list of the Mexican herpetofauna: with a summary of historical and contemporary studies. Zookeys, 1166, 287–306. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.1166.86986

Ramírez-González, C. G., & Canseco Márquez, L. (2015). Chelydra rossignonii, confirmación de su presencia en el estado de Oaxaca. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 86, 832–834. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmb.2015.05.007

Reynoso-Rosales, V. H., Vázquez-Cruz, M. L., & Rivera-Arroyo, R. C. (2016). Estado de conservación, uso, gestión, comercio y cumplimiento de los criterios de inclusión a los Apéndices de la CITES para las especies Claudius

angustatus y Staurotypus triporcatus. Mexico City: Conabio-CITES.

Ríos-Solís, J. A., Lavariega, M. C., García-Padilla, E., & Mata-Silva, V. (2021). Noteworthy records of freshwater turtles in Oaxaca, Mexico. Revista Latinoamericana de Herpetología, 4, 184–191.

Semarnat (Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales). (2010). Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010, Protección ambiental – Especies nativas de México de flora y fauna silvestres – Categorías de riesgo y especificaciones para su inclusión, exclusión o cambio – Lista de especies en riesgo. Diario Oficial de la Federación. 30 de diciembre de 2010, Segunda Sección, México.

Semarnat (Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales). (2012). Informe anual PROFEPA 2012. México D.F.: Semarnat.

Semarnat (Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales). (2025). Proyecto de Norma Oficial Mexicana PROY-NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2025, Protección ambiental – Especies nativas de México de flora y fauna silvestres – Categorías de riesgo y especificaciones para su inclusión, exclusión o cambio – Lista de especies en riesgo. Diario Oficial de la Federación. 14 de abril de 2025, Segunda Sección, México.

Seidel, M. E., & Ernst, C. H. (2017). A systematic review of the turtle family Emydidae. Vertebrate Zoology, 67, 1–122. https://doi.org/10.3897/vz.67.e31535

Spencer, R. J., Van Dyke, J. U., & Thompson, M. B. (2017). Critically evaluating best management practices for preventing freshwater turtle extinctions. Conservation Biology, 6, 1340–1349. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12930

Spinks, P. Q., Thomson, R. C., Gidiş, M., & Shaffer, H. B. (2014). Multilocus phylogeny of the New-World mud turtles (Kinosternidae) supports the traditional classification of the group. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 76, 254–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2014.03.025

Torres-Hernández, L. A., Ramírez-Bautista, A., Cruz-Elizalde, R., Hernández-Salinas, U., Berriozábal-Islas, C., DeSantis, D. L. et al. (2021). The herpetofauna of Veracruz, Mexico: composition, distribution, and conservation status. Amphibian and Reptile Conservation, 15, 72–155.

Turtle Conservation Coalition (TCC: Stanford, C. B., Rhodin, A. G. J., van Dijk, P. P., Horne, B. D., Blanck, T., Goode, E. V., Hudson, R., Mittermeier, R. A., Currylow, A., Eisemberg C. et al.). (2018). Turtles in Trouble: The World’s 25+ Most Endangered Tortoises and Freshwater Turtles—2018. Ojai, California: IUCN SSC Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group, Turtle Conservancy, Turtle Survival Alliance, Turtle Conservation Fund, Chelonian Research Foundation, Conservation International, Wildlife Conservation Society, and Global Wildlife Conservation.

Turtle Taxonomy Working Group (TTWG: Rhodin, A. G. J., Iverson, J. B., Bour, R., Fritz, U., Georges, A., Shaffer, H. B., & van Dijk, P. P.). (2021). Turtles of the World: annotated checklist and atlas of taxonomy, synonymy, distribution, and conservation status. 9th Edition. Chelonian Research Monographs 8. Rochester, NY.

Turtle Taxonomy Working Group (TTWG: Rhodin, A. G. J., Iverson, J. B., Fritz, U., Gallego-García, N., Georges, A., Ihlow, F., Shaffer, H. B., & van Dijk, P. P.). (2025). Turtles of the World: Annotated Checklist and Atlas of Taxonomy, Synonymy, Distribution, and Conservation Status (10th Ed.). Chelonian Research Monographs 9.

Vásquez-Cruz, V., Cazares-Hernández, E., Reynoso-Martínez, A., Kelly-Hernández, A., Fuentes-Moreno A., & Lara-Hernández, F. A. (2021). New distributional records of freshwater turtles from west-central Veracruz, Mexico. Reptiles and Amphibians, 28, 146–151. https://doi.org/10.17161/randa.v28i1.15373

Velázquez-Nucamendi, I. A., García-del Valle, Y., Reyes-Grajales, E., Sánchez-Cortés, M. S., & Ruan-Soto, F. (2021). Usos, prácticas y conocimiento local sobre las tortugas continentales (Testudines: Cryptodira) de la comunidad de Playón de la Gloria, Chiapas, México. Revista de Etnobiología, 19, 46–61.

Wilson, L. D., Mata-Silva, V., & Johnson, J. D. (2013). A conservation reassessment of the reptiles of Mexico based on the EVS measure. Amphibian and Reptile Conservation, 7, 1–47.

Winokur, R. M. (1982). Integumentary appendages of chelonians. Journal of Morphology, 172, 59–74. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmor.1051720106