Spatial distribution and suitable core habitat ofHerichthys labridens in the Media Luna Spring, San Luis Potosí, Mexico

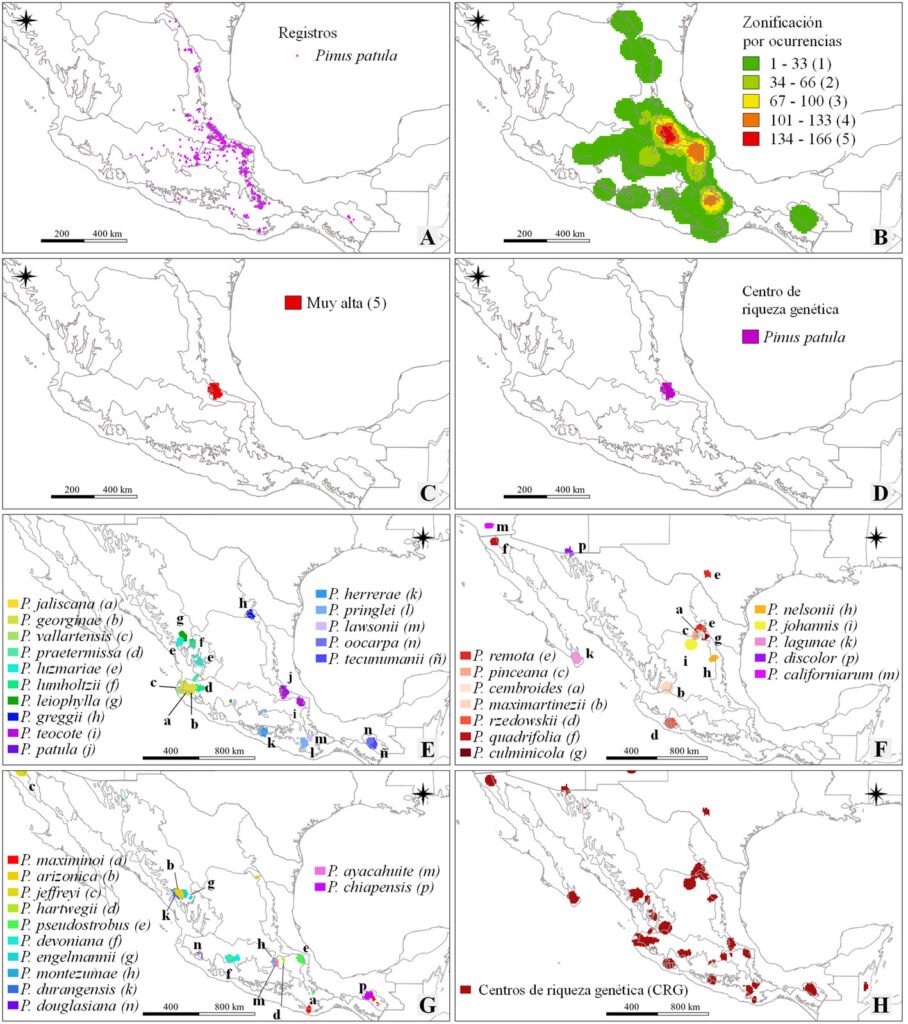

David Walter Rössel-Ramírez a, Jorge Palacio-Núñez b, *, Santiago Espinosa a, Juan Felipe Martínez-Montoya b, Genaro Olmos-Oropeza b

a Universidad Autónoma de San Luis Potosí, Facultad de Ciencias, Av. Parque Chapultepec 1570, Privadas del Pedregal, 78295 San Luis Potosí, San Luis Potosí, Mexico

b Colegio de Postgraduados, Campus San Luis Potosí, Calle de Iturbide 73, San Agustín, 78622 Salinas de Hidalgo, San Luis Potosí, Mexico

*Corresponding author: jpalacio@colpos.mx (J. Palacio-Núñez)

Abstract

The wetland formed by the Media Luna Spring is used for tourism, generating landscape modifications to the habitat of fish populations. Given this, the present study focused on quantifying these changes and correlating them to the spatial distribution and habitat affinity of the endemic cichlid fish Herichthys labridens, over 2 decades. Its spatial distribution was modeled and its suitable core habitat was estimated, considering their adult and juvenile life stages during 3 summer events (1999, 2009, and 2019). Based on occurrence records and the variables of water depth and underwater coverage, the variation in the spatial distribution of this fish species was evaluated in each summer event using the DOMAIN Model. A suitable core habitat was also identified from habitat resistance analysis. The highest probability of distribution (DP > 0.70) of both stages always occurred in areas with a high density of underwater vegetation, with a maximum depth of 1.5 m. On a spatial-temporal scale, the core habitat with medium and high suitability (HR ≤ 0.01) for adults and juveniles was to the extent that maintained its underwater coverage characteristics. This information is important for delimiting a conservation area of H. labridens in the Media Luna Spring.

Keywords: DOMAIN model; Endemic freshwater fish; Habitat resistance; Predictor variables; Semi-arid zones; Spatial-temporal scale

Distribución espacial y hábitat núcleo idóneo de Herichthys labridens en el manantial Media Luna, San Luis Potosí, México

Resumen

El humedal formado por el manantial Media Luna tiene uso turístico, con modificaciones paisajísticas del hábitat de las poblaciones de peces. El presente estudio se enfocó en correlacionar y cuantificar estos cambios con la distribución espacial y afinidad al hábitat del pez endémico Herichthys labridens, en el transcurso de 2 décadas. Se modeló su distribución y se estimó su hábitat núcleo idóneo, considerando sus estadios de vida adulto y juvenil, en 3 eventos de verano (1999, 2009 y 2019). A partir de registros de presencia y las variables profundidad del agua y cobertura subacuática, la variación de la distribución espacial fue evaluada en cada verano mediante el modelo DOMAIN. También se identificó el hábitat núcleo idóneo a partir del análisis de resistencia al hábitat. La mayor probabilidad de distribución (DP > 0.70) de ambos estadios siempre se presentó en zonas con alta densidad de vegetación subacuática, con profundidad máxima de 1.5 m. A escala espacio-temporal, el hábitat núcleo con idoneidad media y alta (HR ≤ 0.01) para adultos y juveniles fue la extensión que conservó sus características de cobertura subacuática. Esta información es importante para delimitar un área de conservación de H. labridens en el manantial Media Luna.

Palabras clave: Modelo DOMAIN; Peces dulceacuícolas endémicos; Resistencia al hábitat; Variables predictoras; Zonas semiáridas; Escala espacio-temporal

Introduction

In freshwater systems (e.g., rivers, lakes, springs) the distribution of each fish species is governed by environmental (e.g., temperature, dissolved oxygen, water chemistry) and habitat (e.g., water depth, underwater coverage) factors (Matthews et al., 2004), that act on a temporal and spatial scale. This has fueled research interest in spatial ecology (Elith & Leathwick, 2009), however, in Mexico, these kinds of studies applied to freshwater fish are scarce, especially for endemic and endangered fishes (Ceballos et al., 2018; de la Vega Salazar, 2003). A great richness of endemic fish inhabits the semi-arid springs (closed-type ecosystems) of the country (Contreras-Balderas, 1969; Contreras-MacBeath et al., 2014; Miller, 1984), having a variable and dynamic allopatric distribution on a temporal and spatial scale (Eby et al., 2003). These native fish communities are well-adapted to various environmental conditions and habitat compositions (Contreras-Balderas, 1969; Miller et al., 2005). Nonetheless, fish species are still susceptible to habitat modifications (e.g., elimination of underwater vegetation) and competition with exotic fishes (Lozano-Vilano et al., 2021; Ruiz-Campos et al., 2006), which constitutes a threat to their survival (de la Vega Salazar, 2003; Torres-Orozco & Pérez-Hernández, 2011).

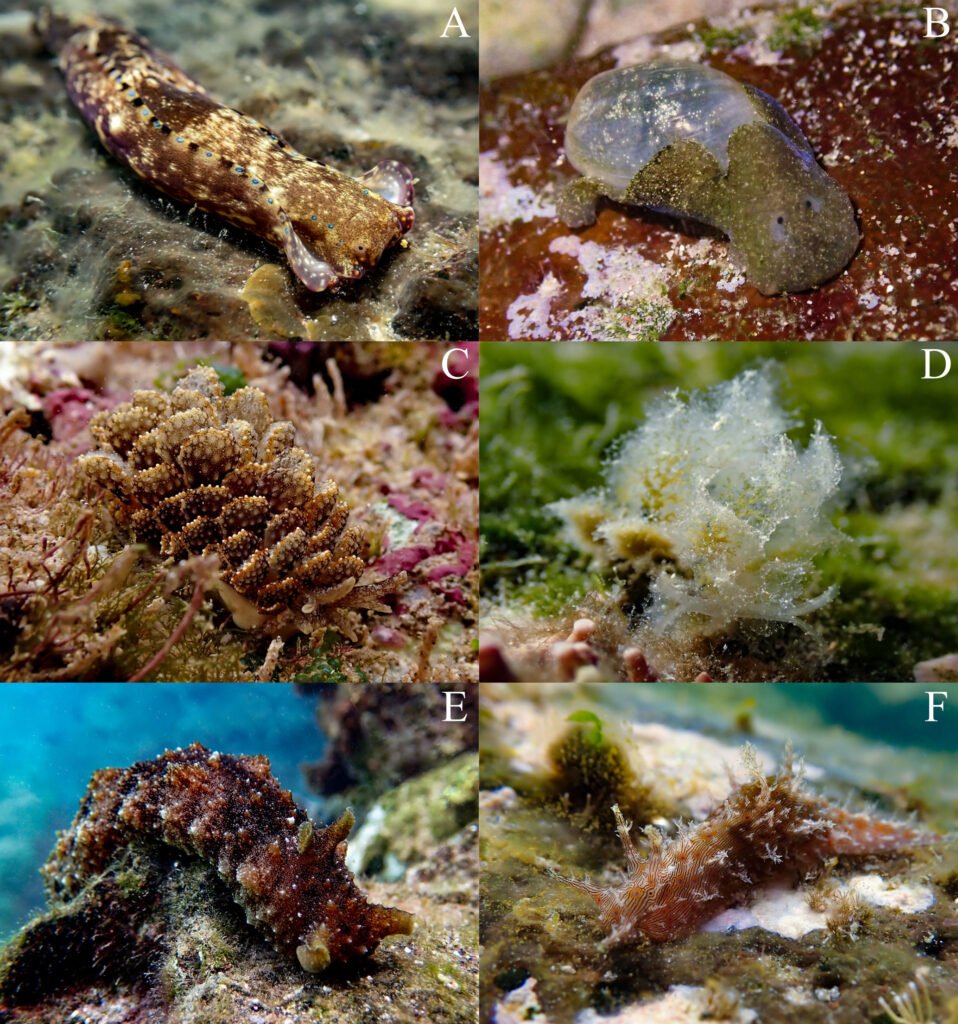

A clear example of a semiarid spring with habitat modification by anthropic pressure is the Media Luna Spring in San Luis Potosí, Mexico (Galván Meza et al., 2018; Palacio-Núñez et al., 2010). This spring stands out for its extension and cultural popularity (Damián-Santiago, 2015), as well as its particular landscape and crystalline-sulfate water of touristic interest (Galván Meza et al., 2018; Salazar et al., 2002). This site is also the habitat of 4 species of endemic fishes (Ceballos et al., 2018) and is the main reservoir of the endemic cichlid Herichthys labridens (Pellegrin, 1903) (Supplementary material: Figure Sup1). In this ecosystem, this species has been documented as a generalist species, with greater activity from ~ 0.1 m to over ~ 10.5 m depth, in sites ranked from highly vegetated to bare bottom (Miller et al., 2005; Palacio-Núñez et al., 2015; Soto-Galera et al., 2019). In addition, H. labridens current population conservation status is endangered (species status maintained by IUCN, 2024).

Although H. labridens is under a conservation category, it is still affected by habitat alterations caused by natural and/or man-made disturbances —e.g., drought, tourist pressure, changes in the composition of underwater vegetation— (Palacio-Núñez et al., 2010; Ruetz III et al., 2005). Therefore, attention must be paid to structural changes in the freshwater ecosystem and the ecological-spatial situation of this species, before reaching a population collapse and the extinction of the species, as has happened with several species in other sites (e.g., Hickley et al., 2004; Miranda et al., 2010). Especially, because the rates of biodiversity loss are higher in freshwater environments than in those of terrestrial and marine systems (Dudgeon et al., 2005; Ricciardi & Rasmussen, 1999). However, information about the degree of preference of H. labridens to its habitat and the variation of its spatial distribution in Media Luna is still scarce, particularly when life stages (i.e., juveniles and adults) are taken into account (Brandt, 1980). Moreover, due to possible habitat degradation, as has happened elsewhere, a study on a temporal scale allows us to determine the variability of habitat resistance for the species (Elith & Leathwick, 2009; Miranda et al., 2010; Ruetz III et al., 2005; Zeller et al., 2012).

Taking this research approach, we hypothesized that in the Media Luna Spring, H. labridens has a heterogeneous distribution preferring geographic spaces with high underwater vegetation density that provide refuge habitat and food availability. In addition, we hypothesized that this species has a possible core habitat in conserved vegetated areas (i.e., low cost of resistance to the habitat). In the present study, we conducted the spatial distribution models for this species in adult and juvenile stages and estimated the suitable core habitat for both stages in 3 summer events separated by an interval of 10 years (years 1999, 2009, and 2019), in the Media Luna Spring. We used a combination of spatial distribution models and habitat resistance analysis to 1) determine the variation in H. labridens distribution, by life stage and to compare this distribution with the configuration of the underwater coverage, 2) convert the distribution probability into habitat resistance cost from the 3 summer events and estimate the suitable core habitat for H. labridens, and 3) also calculate the area of medium and high suitability of the core habitat. Such information is crucial to aid conservation measures for the key habitat of H. labridens.

Materials and methods

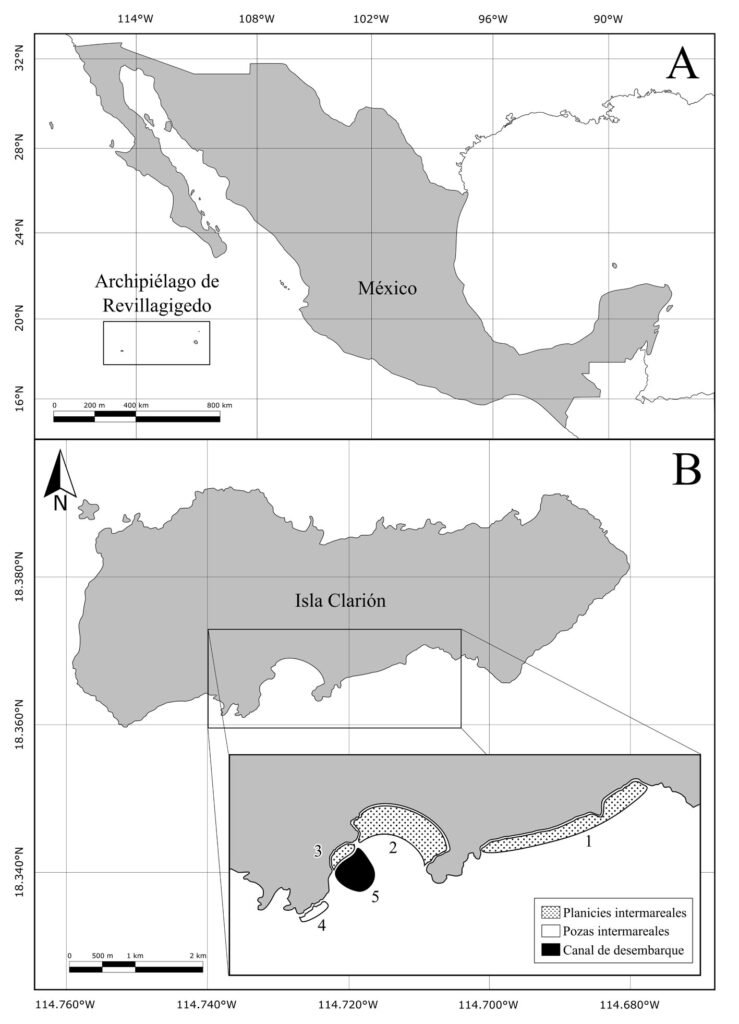

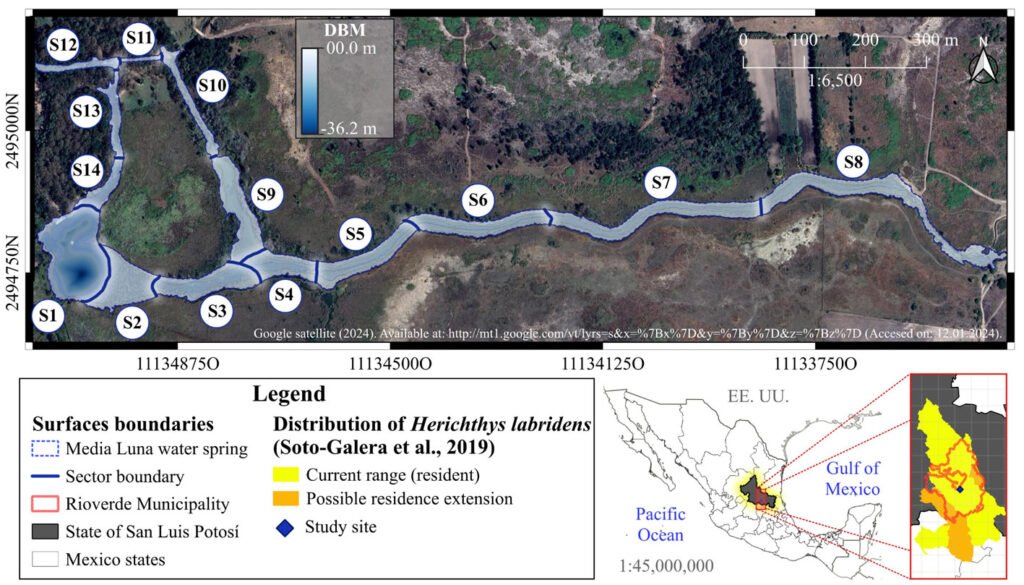

The study was carried out at the Media Luna Spring, which is located in the semi-arid plain of Rioverde, San Luis Potosí, Mexico. We selected this site because it is one of the main reservoirs of H. labridens and is located within the known distribution range of the species (Miller et al., 2005; Palacio-Núñez et al., 2015). Together, the entire system covers ~ 7.49 ha of water surface (Fig. 1). Much of the water surface is covered by the macrophyte Nymphaea ampla (Wiersema et al., 2008), in association with other macrophytes of emergent, sub-emergent, and floating type (pers. obs., Palacio-Núñez, 2007). Given the ecological importance of the Media Luna Spring and the impact caused by tourism (Galván Meza et al., 2018; Macías-Andrade & Maldonado-González, 2011), on 7 June 2003, the site was cataloged as a protected natural area and categorized as a State Park (Periódico Oficial del Gobierno del Estado Libre y Soberano de San Luis Potosí, 2003; Segam, 2019).

To explore the variation in spatial distribution of H. labridens and to estimate its suitable core habitat, according to specific habitat conditions (e.g., water depth and underwater coverage), we studied a 20-year time interval, starting in 1999 (when the information records began) and ending in 2019. We sampled during 3 summer events separated by 10 years (1999, 2009, and 2019). Under these analysis conditions, assumptions about uniform spatial distribution and errors are avoided when evaluating temporal variation (Ruetz III et al., 2005).

In the sampling design and systematization of the spatial-temporal analysis, we used the 14 sectors proposed by Palacio-Núñez et al. (2010), which were delimited according to the composition and structure of the underwater coverage, the depth of the water, and the degree of anthropogenic impact on the ecosystem (S1 to S14; Fig. 1; Supplementary material: Table Sup1). Despite the variations in structure and composition of the system over time, which were mainly due to tourism activities (e.g., diving, recreational swimming, splashing; Galván-Meza et al., 2018), we used the same extension and boundaries of the sectors during the study events. It is important to note that the spatial delimitation and validation of the sectors and the water surface were performed using the QGIS® software version 3.4.8 (Menke, 2019).

Figure 1. Geographic location, surface area and sectorization (S1 to S14) of the study site Media Luna Spring, San Luis Potosí, Mexico. The 3 main canals started from the set of springs in sector 1 (S1), which correspond to the main lagoon. The Digital Bathymetric Model (DBM) served as the basis for the surface of the system. Sectorization was adapted from Palacio-Núñez et al. (2010). Also, it shows the location of the spring at the country, state, and municipality levels, as well as the recorded range of H. labridens distribution (Soto-Galera et al., 2019). Map by authors.

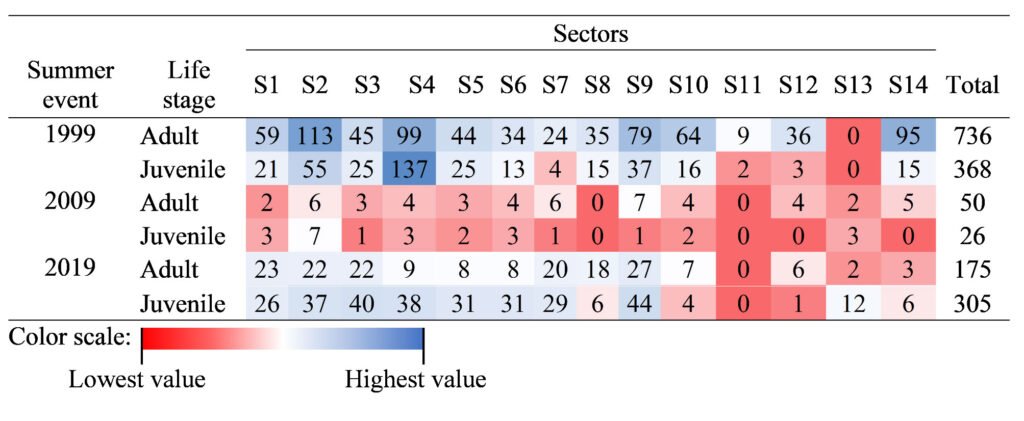

Specifically, during the summer periods, tourism increases at the study site (Galván-Meza et al., 2018), which influences the distributional range and habitat of H. labridens. Therefore, we obtained spatial records of this species, categorized by adult and juvenile life stages, for summer events of 1999, 2009, and 2019 (Table 1). The databases with spatial and habitat filtering were obtained from 2 sources: for 1999, from Palacio-Núñez et al. (2010), and for the subsequent events, from Rössel-Ramírez, Palacio-Núñez, Martínez-Montoya et al. (2024). These authors recorded each occurrence, by life stage, through direct observation method using snorkeling equipment and a GPS device. Also, to avoid registering the same organism twice in the fieldwork, they validated human observation with subaquatic cameras.

Habitat conditions (e.g., vegetation, bottom types, elevation, and depth) influence the distribution of specialist or endemic species (Naoki et al., 2006). In the present study, we selected 2 predictor variables of the underwater habitat. Due to its relationship with the spatial distribution of various fish communities, the first predictor variable was water depth (McClain & Etter, 2005; Palacio-Núñez et al., 2010; Prchalová et al., 2009; Thrush et al., 2006). The second variable was the underwater coverage, which influences the food and habitat for fish fauna (Brosse & Lek, 2002; Brosse et al., 2007; Rozas & Odum, 1988). Both variables are related to abiotic and biotic factors important for fishes, such as temperature, dissolved oxygen (O2), and biomass (Brandt, 1980; Brosse et al., 1999; Gido & Matthews, 2000; Matthews et al., 2004; Straškraba, 1974).

We obtained a digital bathymetric model for water depth (ranging from 0.0 to -36.2 m) and a raster with reclassification of underwater coverage for the 3 summer events (Rössel-Ramírez et al., 2023). The classification of underwater coverage included the “bare bottom” and “macrophyte vegetation” categories proposed by Palacio-Núñez et al. (2010) and Rössel-Ramírez et al. (2023) for the Media Luna Spring. The bare bottom was classified according to 1) depth, referring to bottom below 12 m, where underwater vegetation does not grow (this type of bottom is only present in S1); 2) tourism, which tends to eliminate vegetation from the sites; and 3) natural process, related to bottom clearings derived from sediment accumulation.

The coverage provided by N. ampla was categorized as follows: 1) small carpet, plants smaller than 0.3 m and with high population density; 2) big carpet, plants with stems of variable length between 0.3 to 2.0 m and large ovoid leaves that overlap; and 3) mature shape, plants with floating and spaced leaves with white flowering. In terms of the presence of remnants of emergent vegetation of the big carpet and mature shape type (S10 to S14), the categories were: big carpet patch and mature shape patch. Thus, a total of 8 coverage categories were included. We loaded both water depth and underwater coverage variables into the geographic projection system WGS 84/Pseudo-Mercator (EPSG: 3857), by the summer event, keeping a Ground Sample Distance of 0.1 m.

We used 2 methods in R® and RStudio® (RStudio Team, 2020) to evaluate both predictor variables in each summer event: the percentage of contribution (Dedman et al., 2017; Freund & Schapire, 1997) via a Gradient Boost Machine (GBM) model (Friedman, 2002), and the Pearson´s correlation to determine the multicollinearity or independence between variables (Guisan & Hofer, 2003). In the first method, this model allows us to estimate the relative contribution of predictor variables as a function of the occurrence of H. labridens (Dedman et al., 2017). For the parameterization, using the GBM package, we selected the Gaussian distribution with a cross-validation of 5,000 repetitions. Also, the model was trained with a random subgroup of training (80%) and testing (20%) from occurrence records (Friedman, 2002; Hijmans, 2012). Additionally, we generated 500 background points to validate the models.

In the 3 summer events, both water depth and underwater coverage had a percentage contribution ≥ 2%, so following the criteria of Awan et al. (2021) and Mohammadi et al. (2021), we selected both for our models (Supplementary material: Figure Sup2.). Subsequently, we evaluated the collinearity of the variables using the Pearson correlation coefficient, avoiding having a high redundancy between variables (Guisan & Hofer, 2003). We established a bivariate correlation below ± 0.70 for the 2 variables, based on a literature review (Awan et al., 2021). As a result, both predictor variables were independent in the 3 events and were included for modeling (Supplementary material: Table Sup2).

Distribution models are a suitable tool for understanding the geographic patterns of species over time (Castillo-Torres et al., 2017; Joy & Death, 2002; Maloney et al., 2013). Carpenter et al. (1993) and Naoki et al. (2006) propose DOMAIN as the appropriate model to project the distribution of endemic species. Therefore, to estimate the distribution of H. labridens, by life stage, we ran this model in Rstudio® for the 3 summer events, loading the water depth and underwater coverage variables and the occurrence records. The packages used were: sp (Pebesma, 2021), dismo, raster, maptools (Hijmans & Elith, 2017), RColorBrewer (Neuwirth, 2014), pander (Farlane, 2013), Rcpp, lattice (Sarkar, 2008), caret (Kuhn et al., 2020), pROC (Robin et al., 2011), and sdm (Naimi & Araujo, 2016).

Table 1

Number of occurrence records of H. labridens in the Media Luna spring, San Luis Potosí, Mexico, organized by 3 summer events (years 1999, 2009, and 2019) and life stage (adult and juvenile) in each sector (S1 to S14). The total number of records is included.

Additionally, we generated 500 background points to validate the models; this number was a smaller amount than other studies (e.g., Barbet-Massin et al., 2012) due to the smaller extension of the Media Luna Spring (~7.49 ha). Then, both the occurrences and the background points were subdivided into a training group (80%) and a test group (20%). For modeling, we selected the training groups and the stack containing the variables of water depth and underwater coverage to estimate the DOMAIN probabilistic projections of adult and juvenile stages of H. labridens, in each summer event.

As a last step, we evaluated the prediction performance of each model using the area under the curve (AUC) of the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (Fawcett, 2006). Likewise, we validated the models based on the ROC curve (Fielding & Bell, 1997). The values of the ROC curve were evaluated, following the method of Pearce and Ferrier (2000); according to this method, AUC > 0.5 indicates a model that distinguishes between true presence and absence of a response variable (i.e., occurrence). For partial ROC validation, we followed the Manzanilla-Quiñones (2020) criterion, according to which an AUC ratio value > 1.0 indicates excellent model performance.

The raster layers with spatial distribution probability were loaded into the Qgis® version 3.28.4. We subsequently converted this probability to habitat resistance (Zeller et al., 2012), as a product of the Kernel algorithm, using Equation 1 (Wan et al., 2019):

R = 1000(-1 x SDM)

where R represents the habitat resistance cost assigned to each pixel value and SDM represents the spatial distribution derived from the previously projected models. Additionally, for all raster, the resistance values were rescaled to a range of 0 to 10 by linear interpolation. The minimum resistance (Rmin) was 0 when the distribution probability (DP) was 1, and the maximum resistance (Rmax) was 10 when the DP was 0, following the criterion of Mohammadi et al. (2021).

We calculated the suitability of the core habitat, for H. labridens juveniles and adults, from the accumulation of the habitat resistance cost for the 3 summer events, according to the method of Lawler et al. (2006). This analysis was performed to estimate the accumulation of habitat suitability based on the expected rate of distribution of the species under study (Kaszta et al., 2018).We thus explored the suitable core habitat of H. labridens by life stages.

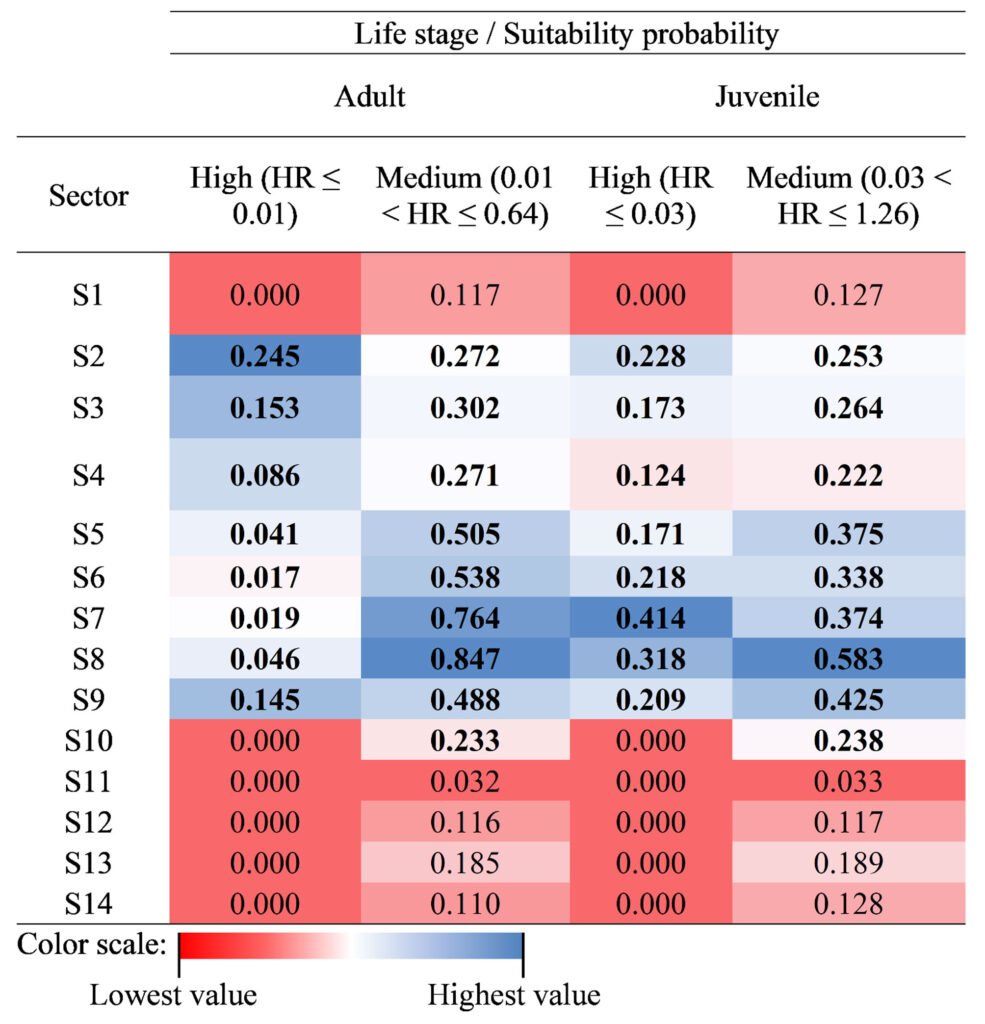

Based on the habitat resistance (HR) and the new scale of the range of values (i.e., 1 to 10), for both life stages, we categorized the suitable core habitat by quantiles; so that the suitable habitat of the species is better adjusted (Anderson et al., 2003; Burneo et al., 2009). Therefore, we categorized the suitability of the habitat into 3 levels: high (adults, HR ≤ 0.01; juveniles, HR ≤ 0.03), medium (adults, 0.01 < HR ≤ 0.64; juveniles, 0.03 < HR ≤ 1.26); and low (adults, HR > 0.64; juveniles, HR > 1.26). The spatial results were used to identify and regionalize the core area, which was a combination of medium and high suitability for both stages (e.g., Brind’Amour et al., 2005; Poizat & Pont, 1996). Additionally, we calculated the area (ha) per sector of both suitability categories for each sector, by life stage, in the Media Luna Spring.

Results

In terms of the performance of the models, based on the ROC/AUC curve, H. labridens adults had AUCs of 0.67, 0.60, and 0.66 in 1999, 2009, and 2019, respectively; and juveniles had AUCs of 0.73, 0.68, and 0.76 in 1999, 2009, and 2019, respectively (Supplementary material: Figure Sup3). In the validation, all models had a density > 2 of positive cases at a predicted value between 0.6 and 0.9 (Supplementary material: Figure Sup4) in the partial ROC plots. In addition, these models presented a Bandwidth < 0.05 and an AUC ratio > 1.0, per life stage and summer event.

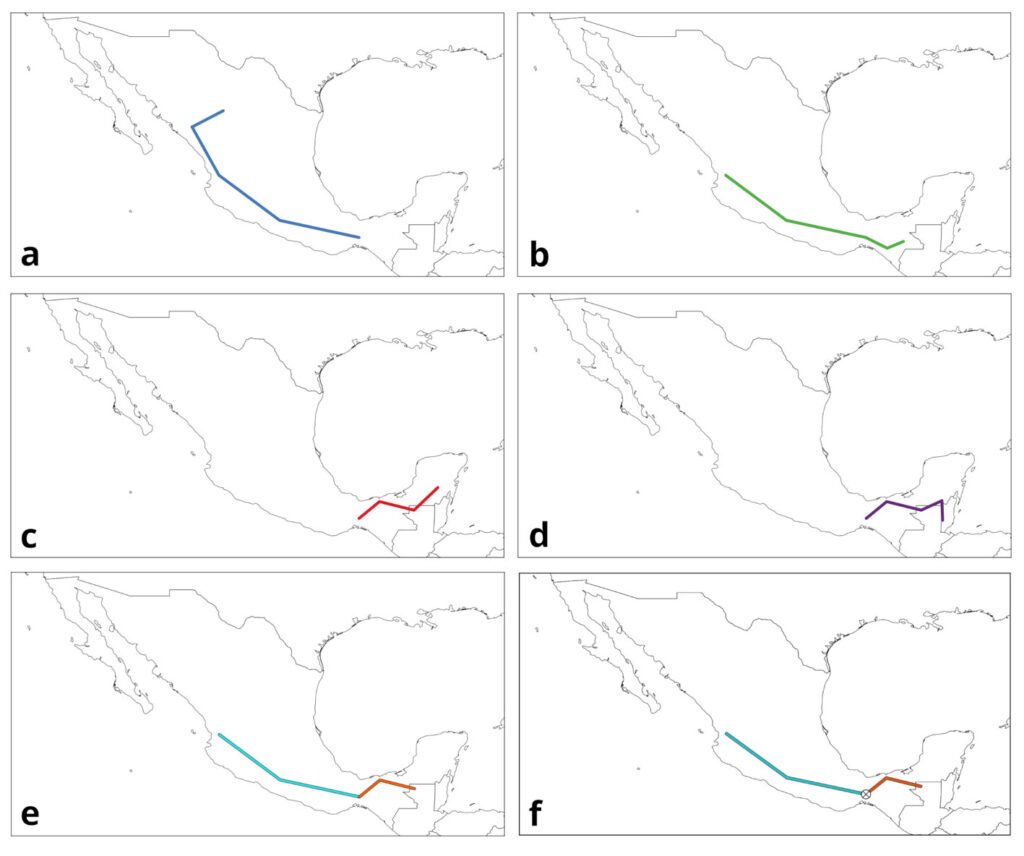

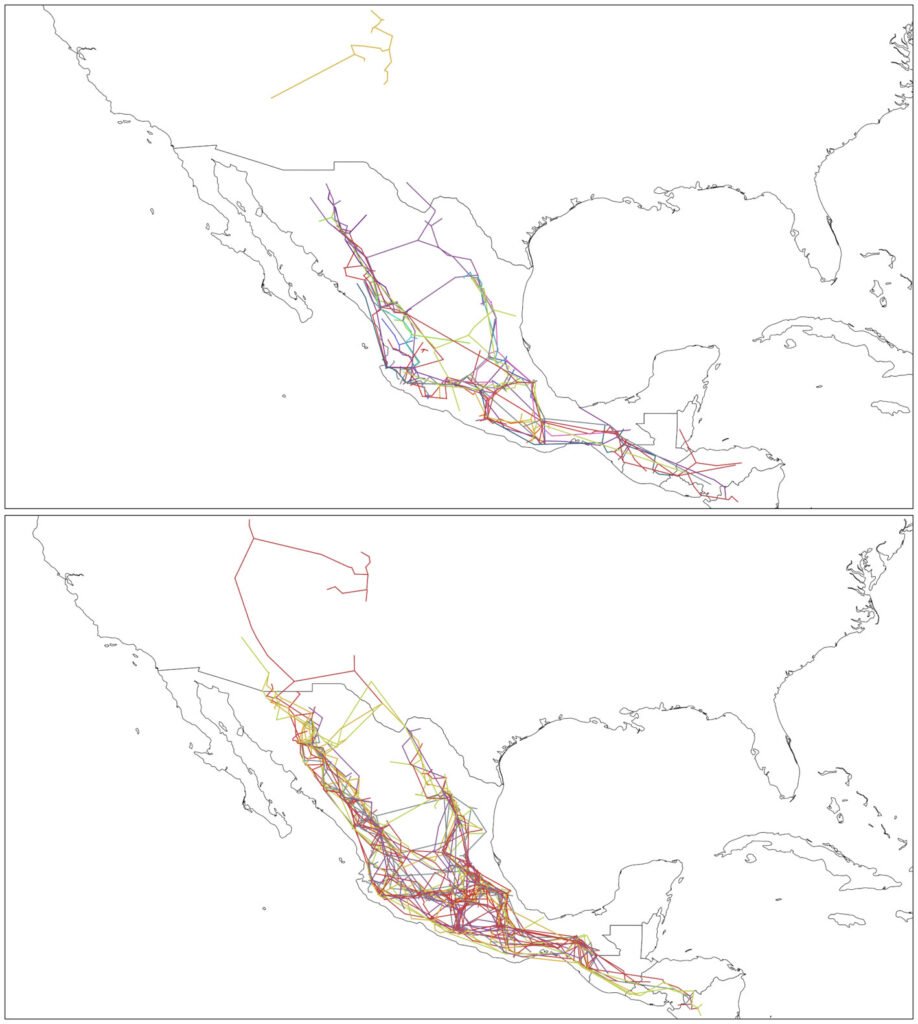

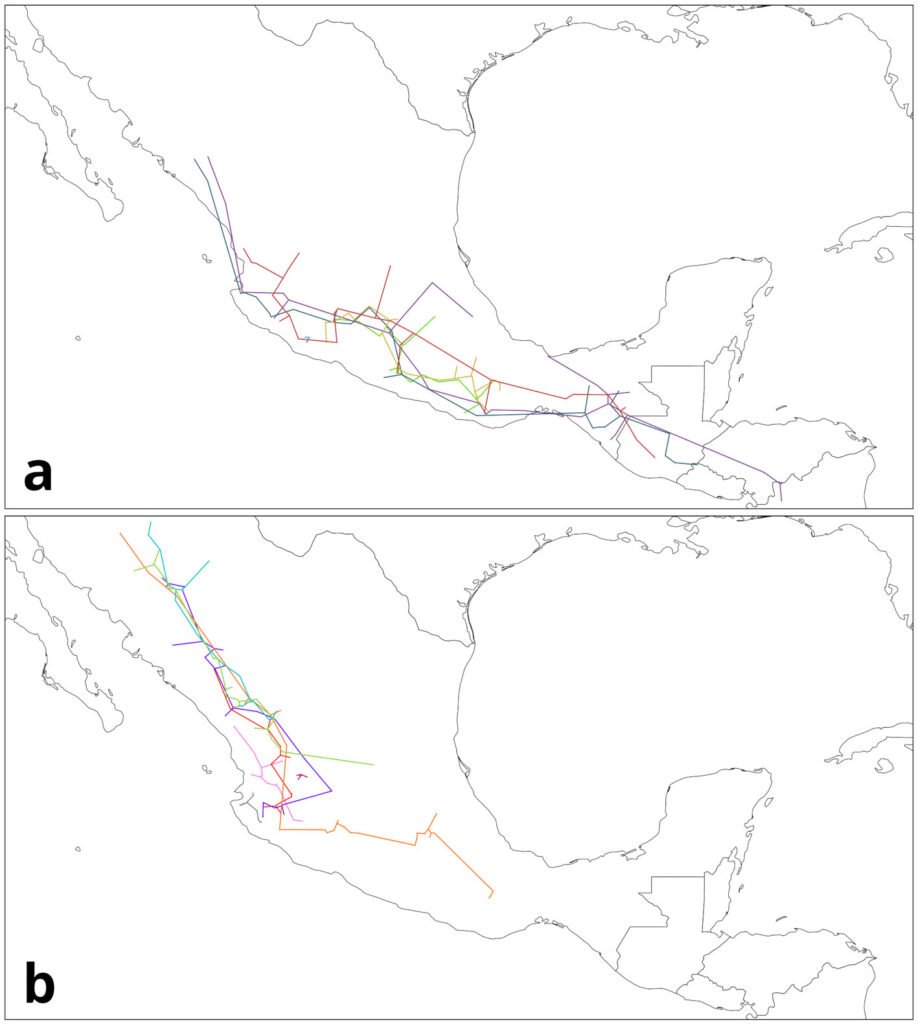

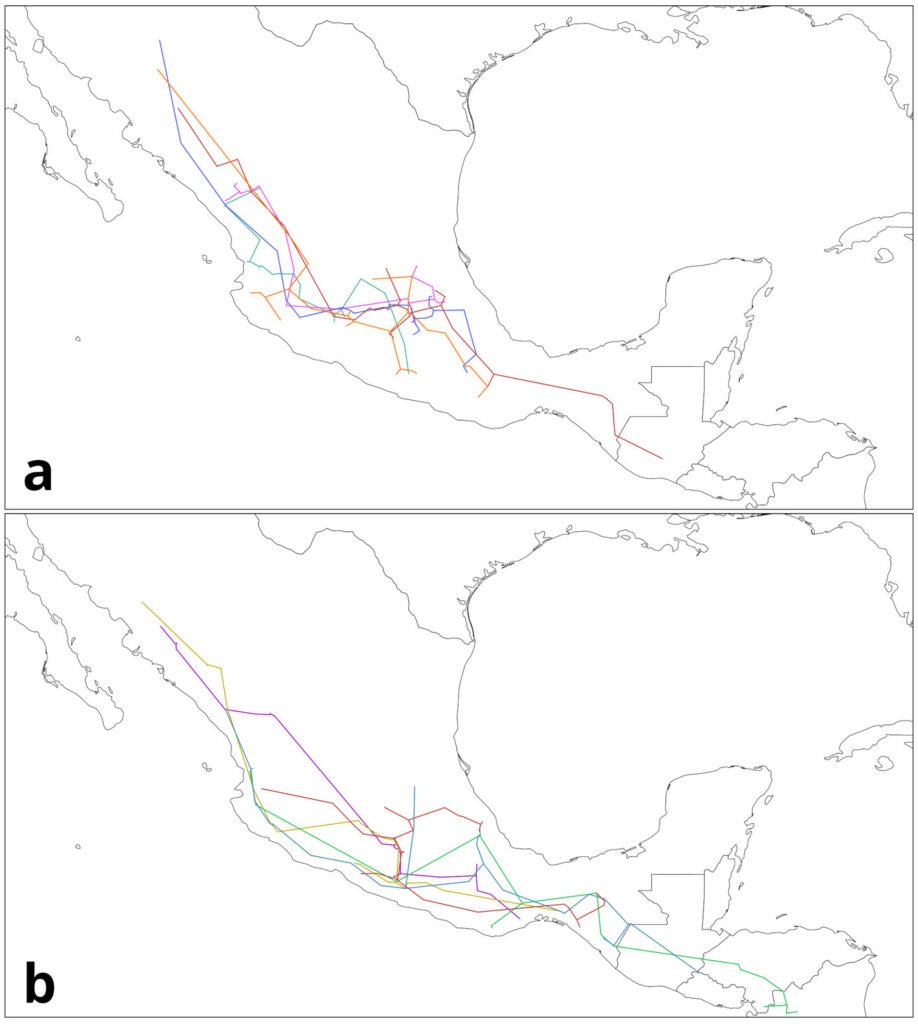

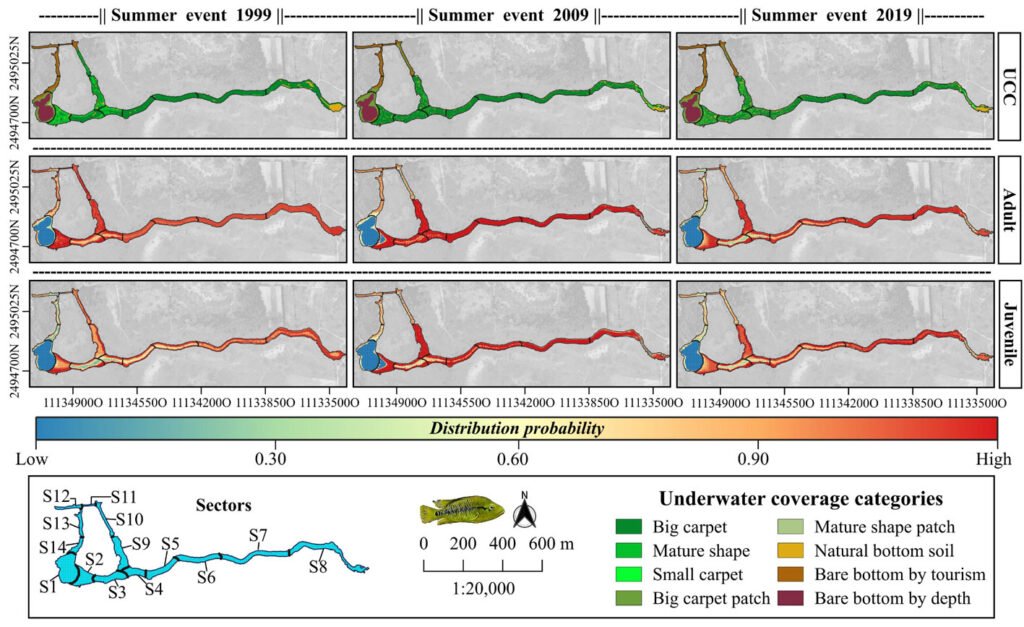

For the adult and juvenile stages of H. labridens, we obtained similar spatial distribution models. In the summer of 1999, the highest probability of distribution (DP > 0.70) was projected in sectors S2-S10; only for adult, the highest probability was too presented in S12. In these sectors, all types of underwater vegetation coverage were present, together with bare bottom by tourism and natural bare bottom; the maximum depth was ~2.5 m. In the following 2 events, the DP > 0.70 was observed only from S2 to S9 which are the sites with the greatest vegetation coverage in big carpet and mature shape (Fig. 2).

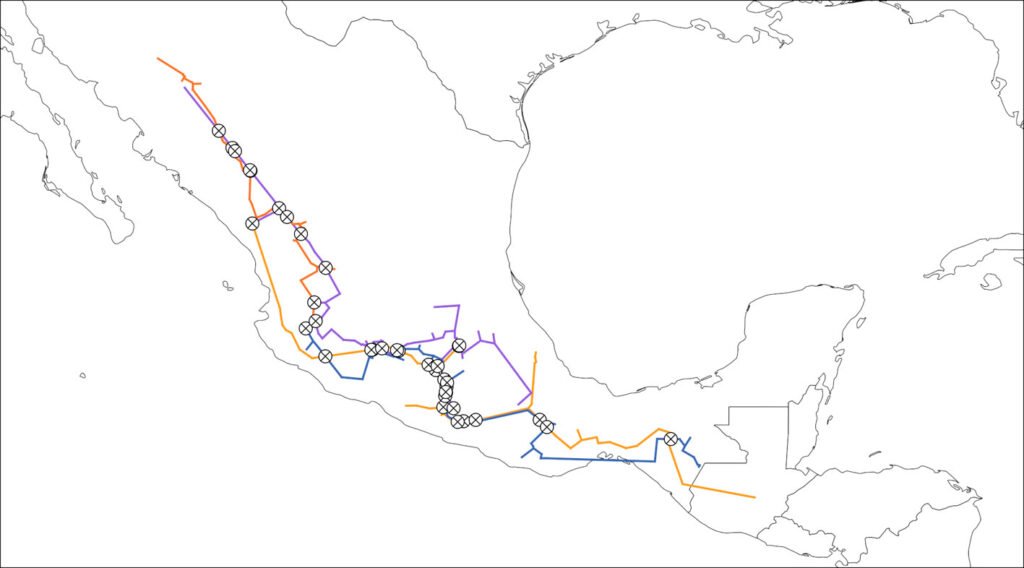

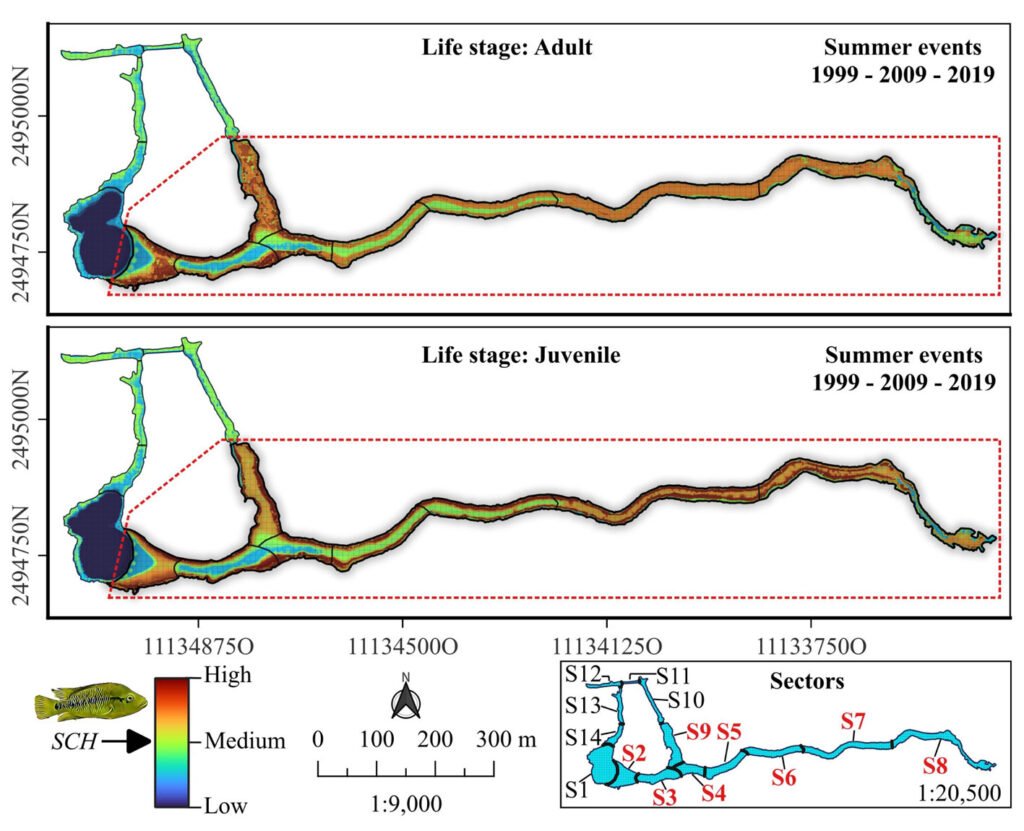

Based on the analysis of HR accumulation in adult and juvenile stages, we identified the highest concentration of high and medium suitability (i.e., medium and low categories of cost of resistance) in sectors S2 to S9 (Fig. 3). For the adult stage, high suitability (RH ≤ 0.01) was observed in sectors S2-S4 and S9. For the juvenile stage, high suitability (RH ≤ 0.03) was observed in sectors S2-S9, particularly close to the shores of the spring. Sectors S1 and S10-S14 presented low and medium suitability for both adult and juvenile stages. Sector S1 had the lowest suitability, which represented the highest HR cost for adults (HR > 0.64) and juveniles (HR > 1.26).

Finally, we calculated the area with high habitat suitability (sectors S2 to S9), with a total area of 0.752 ha for adults and 1.855 ha for juveniles. This represented ~15% and ~36% of the total system extent, respectively. Meanwhile, medium suitability covered an area of 3.987 ha (~ 77%) for adults and 2.834 ha (~ 55%) for juveniles of H. labridens (Table 2). Based on our calculations, the combination of high and medium suitability in sectors S2-S9 covered 4.739 ha for adults and 4.689 ha for juveniles. This represented ~64% of the total area of the spring, now identified as the suitable core habitat for H. labridens. The remaining ~ 36% of the total area of the spring corresponded to sectors S1 and S10-S14, from which ~ 20% corresponded to areas with low habitat suitability in S1 (adults, 1.180 ha; juveniles, 1.169 ha).

Figure 2. Spatial distribution for the adult and juvenile stages of H. labridens in the summer events of 1999, 2009, and 2019, in the Media Luna Spring, San Luis Potosí, Mexico. It is included in the first row the maps with the underwater coverage composition (UCC), by summer event, for a comparison between habitat changes and variations in the distribution of both life stages. The gradient of distribution probability ranges from low (value = 0) to high (value = 1). Map by authors.

Discussion

We have found that, in the Media Luna Spring, in the 3 summer events assessed, the adult and juvenile stages of H. labridens had a higher probability of distribution (DP > 0.70) in sectors S2-S9, which are characterized by high and medium habitat suitability with depth between ~ 0.5 m and ~ 1.5 m. These observations confirm that this species, like the majority of the Perciformes, have dominant spatial patterns in shallow sites, mainly towards the water edge (McClain & Etter, 2005; Prchalová et al., 2009).

In terms of underwater coverage, for a period of 20 years (1999-2019), both the juvenile and adultstages of H. labridens had a higher preference to sectors with high density of vegetation in the categories big carpet and mature shape. The affinity to vegetated sites is easily understood because it ensures both food and refuge (Rozas & Odum, 1988), especially for juveniles (Artigas-Azas, 2004). Furthermore, in these sectors, there are patches of natural bare bottom, which are important for the reproduction of H. labridens; as has been observed in other cichlids studied (Miller, 1984: Miller et al., 2005). Brandt (1980) found similar conditions on habitat selection and spatial segregation for Perciformes in Lake Michigan, USA. Likewise, Brosse and Lek (2002) reported the assembly of geographic patterns of Eurasian perch (Perca fluviatilis) by habitat affinity in the littoral zone of Lake Pareloup, France.

Figure 3. Spatial analysis of suitable core habitat (SCH) for H. labridens at the Media Luna Spring, San Luis Potosí, Mexico. For adult and juvenile stages, each map was generated from the addition of habitat resistance between the 3 summer events (years of 1999, 2009, and 2019). The red dashed contour polygon delineates the region that include the sectors (S2 to S9) with medium- and high-suitability categories, while the outer sectors include the low and medium suitability (S1 and S10 to S14). Map by authors.

In the evaluation of the distribution models by the ROC/AUC curve, Fielding and Bell (1997) and Fawcett (2006) indicate that an AUC > 0.90 represents excellent prediction performance for species distribution models. However, Deshpande (2020) indicates that an AUC between 0.60 and 0.80 constitutes a better prediction classifier, more in line with the ecological reality of the species. Based on this, our models had AUC values ranging from 0.60 to 0.76 for both the adult and juvenile stages in the 3 summer events. We thus conclude that our models had high sensitivity and low specificity, features that correspond to a high discrimination power, in at least ~ 60% of positive cases of occurrence and prediction performance (false positives rate was < 40%). In addition, in the validation by partial ROC, the models had a bandwidth < 0.05 and an AUC ratio > 1.0. Therefore, according to Manzanilla-Quiñones (2020), our models had statistical and ecological significance, across the 3 events of analysis. Thus, we considered that there was a good correlation between habitat variables and the occurrence of H. labridens to allow accurate modeling of its spatial distribution.

Table 2

Area (ha) by suitability category (medium and high) of the core habitat for H. labridens adults and juveniles in the Media Luna Spring, San Luis Potosí, Mexico. The area was calculated for each one from 14 sectors. The values in bold denote the greatest area occupied based on the suitability probability. In most cases, the greatest and most representative areas were between sectors S2 and S9.

Our DOMAIN models provided a good overview of the variation in the spatial distribution of the endemic H. labridens, in both life stages. In addition to that, previous work (Hirzel et al., 2006; Zeller et al., 2012) indicates that estimating core habitats is more accurate when work is carried out over long temporal scales, because it was possible to discern between low, medium, and high resistance habitat, according to the relevant variables (Lawler et al., 2006). Following this, our maps and tables of the suitable core habitat for H. labridens were more conclusive in quantifying its cost of resistance according to the variables of water depth and underwater coverage. We confirmed that the sectors S2-S9 represent the suitable core habitat for H. labridens in the adult and juvenile stages for 20 years at least. These sectors presented low-cost resistance values (i.e., high suitability of core habitat) in adults (RH < 0.01) and juveniles (RH < 0.03), especially towards the shores of the spring, where the maximum depth was ~ 1.5 m and the underwater vegetation coverage was big carpet and mature shape.

It should be noted that the Media Luna Spring has been modified by tourism (Damián-Santiago, 2015; Galván-Meza et al., 2018), causing changes in the composition of underwater coverage for over 2 decades. This was reflected in the progressive decrease in vegetation coverage, although the depth was not noticeably affected, where more than 90% of the spring surface area maintained a depth of less than 3.5 m (pers. obs.). Thus, the distribution area and core habitat, as well as a higher number of occurrences, from S2 to S9 for both adult and juvenile stages, is likely related to habitat degradation in tourism sectors, as has happened in other sites (Hickley et al., 2004; Miranda et al., 2010). Particularly, 2009 was a critical year due to habitat pressure from tourism (Chávez, 2016), linked to the drastic decrease in occurrences for both life stages. Despite this habitat pressure, this speciessurvives and reproduces in this water system, but in a suboptimal population state. Therefore, it is important to keep H. labridens under the category of endangered species as a conservation measure (Miranda et al., 2009).

In conclusion, we found that the suitable core habitat for H. labridens in Media Luna Spring is the region between S2 and S9, which is characterized by a combination of shallow sites associated with dense coverage of emergent, sub-emergent, and floating vegetation patches. It is important to note that these coverage combinations provide resources for feeding and habitat refuge. This information, obtained on a temporal scale, is important to increase our knowledge about the variation in spatial distribution and core habitat of this endemic and threatened species. With this, it is now possible to compare and associate occurrence records with changes in vegetation coverage or anthropogenic pressure. Based on our findings, we urgently propose establishing this estimated core habitat (sectors S2-S9) as a priority conservation area for H. labridens. This means that these sectors, located in the eastern region of the spring, should be adequately managed without eliminating vegetation or modifying the natural system. Meanwhile, Sectors S1 and S10 to S14 would be categorized as suitable for tourism use, with management and monitoring by the local authorities and ejido leaders at the site.

In addition, we consider that our study provides relevant information on the abundance and habitat preferences of H. labridens to update the management plan and implement habitat care campaigns for the Media Luna Spring. At the same time, to include reports for other endemic species in this spring, as A. toweri (Rössel-Ramírez, Palacio-Núñez, Espinosa et al., 2024). Taken together, our spatial results reinforce the importance of identifying conservation areas or regions in this semi-arid spring.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jesús Enríquez for their participation in fieldwork during the sampling events. In addition, we thank to the Secretaría de Ecología y Gestión Ambiental (Segam; Oficio: ECO.05.1068), the local authorities of Rioverde municipality, and the Jabalí ejido council for allowing us to carry out this study in the Media Luna Spring.

References

Anderson, R. P., Lew, D., & Peterson, A. T. (2003). Evaluating predictive models of species’ distributions: criteria for selecting optimal models. Ecological Modelling, 162, 211–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3800(02)00349-6

Artigas-Azas, J. M. 2004). “Herichthys labridens (Pellegrin, 1903)”. Cichlid Room Companion. Retrieved on January 1rst, 2024 from: https://cichlidae.com/species.php?id=209&lang=es. (crc10342)

Awan, M. N., Saqib, Z., Buner, F., Lee, D. C., & Pervez, A. (2021). Using ensemble modeling to predict breeding habitat of the red-listed Western Tragopan (Tragopan melanocephalus) in the Western Himalayas of Pakistan. Global Ecology and Conservation, 31, e01864. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2021.e01864

Barbet-Massin, M., Jiguet, F., Albert, C. H., & Thuiller, W. (2012). Selecting pseudo-absences for species distribution models: how, where and how many? Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 3, 327–338. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2041-210x.2011.00172.x

Brandt, S. B. (1980). Spatial segregation of adult and young-of-the-year alewives across a thermocline in Lake Michigan. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society, 109, 469–478. https://doi.org/10.1577/1548-8659(1980)109<469:SSOAAY>2.0.CO;2

Brind’Amour, A., Boisclair, D., Legendre, P., & Borcard, D. (2005). Multiscale spatial distribution of a littoral fish community in relation to environmental variables. Limnology and Oceanography, 50, 465–479. https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.2005.50.2.0465

Brosse, S., Grossman, G. D., & Lek, S. (2007). Fish assemblage patterns in the littoral zone of a European reservoir. Freshwater Biology, 52, 448–458. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2427.2006.01704.x

Brosse, S., & Lek, S. (2002). Relationships between environmental characteristics and the density of age-0 Eurasian perch Perca fluviatilis in the littoral zone of a lake: a nonlinear approach. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society, 131, 1033–1043. http://dx.doi.org/10.1577/1548-8659(2002)131<1033:RBECAT>2.0.CO;2

Brosse, S., Lek, S., & Dauba, F. (1999). Predicting fish distribution in a mesotrophic lake by hydroacoustic survey and artificial neural networks. Limnology and Oceanography, 44, 1293–1303. https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.1999.44.5.1293

Burneo, S., González-Maya, J. F., & Tirira, D. (2009). Distribution and habitat modelling for Colombian weasel Mustela felipei in the Northern Andes. Small Carnivore Conservation, 41, 41–45.

Castillo-Torres, P. A., Martínez-Meyer, E., Córdova-Tapia, F., & Zambrano, L. (2017). Potential distribution of native freshwater fish in Tabasco, Mexico. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 88, 415–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmb.2017.03.001

Carpenter, G., Gillison, A. N., & Winter, J. (1993). DOMAIN: a flexible modelling procedure for mapping potential distributions of plants and animals. Biodiversity & Conservation, 2, 667–680.

Ceballos, G., Pardo, E. D., Estévez, L. M., & Pérez, H. E. (2018). Los peces dulceacuícolas de México en peligro de extinción. Fondo de Cultura Económica. Cd. de México.

Chávez, M. G. G. (2016). El impacto del turismo en la conservación de la biodiversidad en San Luis Potosí. Sociedad y Ambiente, 11, 148–159.

Contreras-Balderas, S. (1969). Perspectivas de la ictiofauna en las zonas áridas del norte de México. In Simposium Internacional sobre Aumento de Producción de Alimentos en Zonas Áridas. Centro Internacional de Estudios sobre Tierras Áridas, Universidad de Texas Tech.

Contreras-MacBeath, T., Rodríguez, M. B., Sorani, V., Goldspink, C., & Reid, G. M. (2014). Richness and endemism of the freshwater fishes of Mexico. Journal of Threatened Taxa, 6, 5421–5433. https://doi.org/10.11609/JoTT.o3633.5421-33

Damián-Santiago, F. I. (2015). Caracterización del perfil del ecoturista que visita el Parque Estatal Manantial de la Media Luna, en el Ejido El Jabalí, municipio de Rioverde, San Luis Potosí, México (Bachelor’s Thesis). Departamento Forestal, Universidad Autónoma Agraria Antonio Narro. Saltillo, Coahuila, México.

Dedman, S., Officer, R., Clarke, M., Reid, D. G., & Brophy, D. (2017). Gbm. auto: a software tool to simplify spatial modelling and Marine Protected Area planning. Plos One, 12, e0188955. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0188955

De la Vega-Salazar, M. Y. (2003). Situación de los peces dulceacuícolas en México. Ciencias, 72, 20–30.

Deshpande, R. (2020). ROC Curve and AUC in Machine learning and R pROC Package. Retrieved on September 08th, 2023 from: https://medium.com/swlh/roc-curve-and-auc-detailed-understanding-and-r-proc-package-86d1430a3191

Dudgeon, D., Arthington, A. H., Gessner, M. O., Kawabata, Z. I., Knowler, D. J., Lévêque, C. et al. (2005). Freshwater biodiversity: importance, threats, status and conservation challenges. Biological Reviews, 81, 163. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1464793105006950

Eby, L. A., Fagan, W. F., & Minckley, W. L. (2003). Variability and dynamics of a desert stream community. Ecological Applications, 13, 1566–1579. https://doi.org/10.1890/02-5211

Elith, J., & Leathwick, J. R. (2009). Species distribution models: ecological explanation and prediction across space and time. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 40, 677–697. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.110308.120159

Farlane, J. M. (2013). Pandoc User’s Guide. Accessed on RStudio: Integrated Development for R. RStudio, PBC, Boston, MA URL: http://www.rstudio.com/

Fawcett, T. (2006). An introduction to ROC analysis. Pattern Recognition Letters, 27, 861–874. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patrec.2005.10.010

Fielding, A. H., & Bell, J. F. (1997). A review of methods for the assessment of prediction errors in conservation presence/absence models. Environmental Conservation, 24, 38–49.

Freund, Y., & Schapire, R. E. (1997). A decision-theoretic generalization of on-line learning and an application to boosting. Journal of Computer and System Sciences, 55, 119–139. https://doi.org/10.1006/jcss.1997.1504

Friedman, J. H. (2002). Stochastic gradient boosting. Computational Statistics and Data Analysis, 38, 367–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-9473(01)00065-2

Galván-Meza, C. J., Flores-Castillo, E., Espericueta-Bocanegra, E. D., & Gutiérrez-Pérez, M. G. (2018). Análisis del impacto multidisciplinar del turismo dentro del ejido El Jabalí – Media Luna – San Luis Potosí. Medio Ambiente, Sustentabilidad y Vulnerabilidad Social, 5, 419–434.

Gido, K. B., & Matthews, W. J. (2000). Dynamics of the offshore fish assemblage in a southwestern reservoir (Lake Texoma, Oklahoma-Texas). Copeia, 2000, 917–930. http://dx.doi.org/10.1643/0045-8511(2000)000[0917:DOTOFA]2.0.CO;2

Guisan, A., & Hofer, U. (2003). Predicting reptile distributions at the mesoscale: relation to climate and topography. Journal of Biogeography, 30, 1233–1243. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2699.2003.00914.x

Hickley, P., Muchiri, M., Boar, R., Britton, R., Adams, C., Gichuru, N. et al. (2004). Habitat degradation and subsequent fishery collapse in Lakes Naivasha and Baringo, Kenya. International Journal of Ecohydrology & Hydrobiology, 4, 503–517. http://karuspace.karu.ac.ke/handle/20.500.12092/1918

Hijmans, R. J. (2012). Cross-validation of species distribution models: removing spatial sorting bias and calibration with a null model. Ecology, 93, 679–688. https://doi.org/10.1890/11-0826.1

Hijmans, R. J., & Elith, J. (2017). Species distribution modeling with R. R CRAN Project. https://www.researchgate.net/file.PostFileLoader.html?id=5730d34496b7e4bb46356f31&assetKey=AS%3A359897272209410%401462817604682

Hirzel, A. H., Le Lay, G., Helfer, V., Randin, C., & Guisan, A. (2006). Evaluating the ability of habitat suitability models to predict species presences. Ecological Modelling, 199, 142–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2006.05.017

IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature). (Version 2024.2). The IUCN red list of threatened species. Retrieved on January 25th, 2024 from: https://www.iucnredlist.org/

Joy, M. K., & Death, R. G. (2002). Predictive modelling of freshwater fish as a biomonitoring tool in New Zealand. Freshwater Biology, 47, 2261–2275. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2427.2002.00954.x

Kaszta, Ż., Cushman, S. A., Sillero-Zubiri, C., Wolff, E., & Marino, J. (2018). Where buffalo and cattle meet: modelling interspecific contact risk using cumulative resistant kernels. Ecography, 41, 1616–1626. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.03039

Kuhn, M., Wing, J., Weston, S., Williams, A., Keefer, C., Engelhardt, A. et al. (2020). Package ‘caret’: classification and regression training, R-package version 6.0-p. Misc Functions for Training and Plotting Classification and Regression Models.

Lawler, J. J., White, D., Neilson, R. P., & Blaustein, A. R. (2006). Predicting climate-induced range shifts: model differences and model reliability. Global Change Biology, 12, 1568–1584. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2006.01191.x

Lozano-Vilano, M. L., Contreras-Balderas, A. J., Ruiz-Campos, G., & García-Ramírez, M. E. (2021). Current conservation status of some freshwater species and their habitats in México. In D. L. Propst, J. E, Williams, K. R. Bestgen, & C. W. Hoagstrom (Eds.), Standing between life and extinction: ethics and ecology of conserving aquatic species in North American deserts (pp. 79–88). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Macías-Andrade, M. E., & Maldonado-González, D. P. (2011). La práctica ecoturística en el Parque Estatal de la Media Luna en Rioverde SLP (Tesis). Facultad de Economía, Universidad Autónoma de San Luis Potosí. San Luis Potosí, México.

Maloney, K. O., Weller, D. E., Michaelson, D. E., & Ciccotto, P. J. (2013). Species distribution models of freshwater stream fishes in Maryland and their implications for management. Environmental Modeling & Assessment, 18, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10666-012-9325-3

Manzanilla-Quiñones, U. (2020). Validación de modelos de distribución con ayuda de la plataforma niche toolbox de Conabio. Retrieved on June 29th, 2023 from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/341820933

Matthews, W. J., Gido, K. B., & Gelwick, F. P. (2004). Fish assemblages of reservoirs, illustrated by Lake Texoma (Oklahoma-Texas, USA) as a representative system. Lake and Reservoir Management, 20, 219–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/07438140409354246.

Menke, K. (2019). Discover QGIS 3. x. Locate Press.

McClain, C. R., & Etter, R. J. (2005). Mid-domain models as predictors of species diversity patterns: bathymetric diversity gradients in the deep sea. Oikos, 109, 555–566. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0030-1299.2005.13529.x

Miller, R. R. (1984). La Media Luna, San Luis Potosí, at edge of Chihuahua Desert, México. In Proceedings of the Desert Fishes Council Co. (Ed.). Volumes XVI-XVIII. Annual Symposium Bishop, CA. 67–72.

Miller, R. R., Minckley, W. L., Norris, S. M., & Gach, M. H. (2005). Freshwater fishes of Mexico (Núm. QL 629. M54 2005). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Miranda, L. E., Spickard, M., Dunn, T., Webb, K. M., Aycock, J. N., & Hunt, K. (2010). Fish habitat degradation in US reservoirs. Fisheries, 35, 175–184. https://doi.org/10.1577/1548-8446-35.4.175

Miranda, R., Monks, S., Galicia, D., & Pulido-Flores, G. (2009). Threatened fishes of the world: Herichthys labridens (Pellegrin, 1903). Environmental Biology of Fishes, 86, 377. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10641-009-9528-x

Mohammadi, A., Almasieh, K., Nayeri, D., Ataei, F., Khani, A., López-Bao, J. V. et al. (2021). Identifying priority core habitats and corridors for effective conservation of brown bears in Iran. Scientific Reports, 11, 1044. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-79970-z

Naimi, B., & Araujo, M. B. (2016). sdm: a reproducible and extensible R platform for species distribution modelling. Ecography, 39, 368–375. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.01881

Naoki, K., Gómez, M. I., López, R. P., Meneses, R. I., & Vargas, J. (2006). Comparación de modelos de distribución de especies para predecir la distribución potencial de vida silvestre en Bolivia. Ecología en Bolivia, 41, 65–78.

Neuwirth, E. (2014). RColorBrewer: ColorBrewer palettes. R package version 1.1-2. The R Foundation.

Palacio-Núñez, J. (2007). Designación de zonas prioritarias de conservación en el Parque Estatal de la Media Luna (México): utilización de aves y peces como bioindicadores (Ph.D. Thesis). Instituto de Investigación de la Biodiversidad (CIBIO), Universidad de Alicante. Alicante, España.

Palacio-Núñez, J., Olmos-Oropeza, G., Verdú, J. R., Galante, E., Rosas-Rosas, O. C., Martínez-Montoya, J. F. et al. (2010). Traslape espacial de la comunidad de peces dulceacuícolas diurnos en el sistema de humedal Media Luna, Rioverde, SLP, México. Hidrobiológica, 20, 21–30.

Palacio-Núñez, J., Martínez-Montoya, J. F., Olmos-Oropeza, G., Martínez-Calderas, J. M., Clemente-Sánchez, F., & Enríquez, J. (2015). Distribución poblacional y abundancia de los peces endémicos de la Llanura de Rioverde, SLP, México. Agroproductividad, 8, 17–24.

Pearce, J., & Ferrier, S. (2000). Evaluating the predictive performance of habitat models developed using logistic regression. Ecological Modelling, 133, 225–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3800(00)00322-7

Pebesma, E. (2021). Map overlay and spatial aggregation in sp, Report 253. Institute for Geoinformatics. University of Muenster, Weseler Strasse.

Pellegrin, J. (1903). Description de Cichlidés nouveax de la collection du Muséum. Bulletin du Musée National d’Histoire Naturelle, 9, 120–125.

Periódico Oficial del gobierno del estado libre y soberano de San Luis Potosí (07 de junio de 2003). Declaración de Área Natural Protegida bajo la modalidad de “Parque Estatal” denominado “Manantial de la Media Luna”. Retrieved on October 07th, 2023 from: http://201.144.107.246/InfPubEstatal2/_SECRETAR%C3%8DA%20DE%20ECOLOG%C3%8DA%20Y%20GESTI%C3%93N%20AMBIENTAL/Art%C3%ADculo%2018.%20fracc.%20II/Normatividad/Decretos/Decreto%20Media%20Luna.pdf. Secretaría General de Gobierno, 2–12.

Poizat, G., & Pont, D. (1996). Multi-scale approach to species–habitat relationships: juvenile fish in a large river section. Freshwater Biology, 36, 611–622. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2427.1996.00129.x

Prchalová, M., Kubečka, J., Čech, M., Frouzová, J., Draštík, V., Hohausová, E. et al. (2009). The effect of depth, distance from dam and habitat on spatial distribution of fish in an artificial reservoir. Ecology of Freshwater Fish, 18, 247–260. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0633.2008.00342.x

Ricciardi, A., & Rasmussen, J. B. (1999). Extinction rates of North American freshwater fauna. Conservation Biology, 13, 1220–1222. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1739.1999.98380.x

Robin, X., Turck, N., Hainard, A., Tiberti, N., Lisacek, F., Sánchez, J. et al. (2011). “pROC: an open-source package for R and S+ to analyze and compare ROC curves”. BMC Bioinformatics, 12, 1–77. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-12-77

Rössel-Ramírez, D. W., Palacio-Núñez, J., Espinosa, S., & Martínez-Montoya, J. F. (2023). Raster layers of underwater coverage and water depth of the Media Luna spring, Mexico, generated from data from three summer periods (in the years 1999, 2009, and 2019). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10253601

Rössel-Ramírez, D. W., Palacio-Núñez, J., Martínez-Montoya, J. F., & Espinosa, S. (2024). Occurrences records of Herichthys labridens (Cichliformes: Cichlidae), with associated habitat information, in the Media Luna spring, San Luis Potosí, Mexico (Version 1) [Data set]. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14231104

Rössel-Ramírez, D. W., Palacio-Núñez, J., Espinosa, S., & Martínez-Montoya, J. F. (2024). Temporal variation in the relative abundance, suitable habitat selection, and distribution of Ataeniobius toweri (Meek, 1904) (Goodeidae), by life stages, in the Media Luna spring, Mexico. Environmental Biology of Fishes, 107, 173–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10641-024-01520-7

Rozas, L. P., & Odum, W. E. (1988). Occupation of submerged aquatic vegetation by fishes: testing the roles of food and refuge. Oecologia, 77, 101–106. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4218746

RStudio Team (2020). RStudio: Integrated Development for R. RStudio, PBC, Boston, MA URL: http://www.rstudio.com/

Ruetz III, C. R., Trexler, J. C., Jordan, F., Loftus, W. F., & Perry, S. A. (2005). Population dynamics of wetland fishes: spatio-temporal patterns synchronized by hydrological disturbance? Journal of Animal Ecology, 74, 322–332. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2656.2005.00926.x

Ruiz-Campos, G., Camarena-Rosales, F., Contreras-Balderas, S., Reyes-Valdez, C. A., De La Cruz-Agüero, J., & Torres-Balcázar, E. (2006). Distribution and abundance of the endangered killifish, Fundulus lima (Teleostei: Fundulidae), in oases of central Baja California Peninsula, Mexico. The Southwestern Naturalist, 51, 502–509.

Salazar, H. C., Sáenz, E. O., & Rivera, J. R. A. (2002). Agua de riego en la región de Rioverde, San Luis Potosí, México. Tecnología y Ciencias del Agua, 17, 37–56.

Sarkar, D. (2008). lattice: multivariate data visualization with R. Springer-Verlag, New York. http://lmdvr.r-forge.r-project.org/

Segam (Secretaría de Ecología y Gestión Ambiental). (2019). Declaratoria de Área Natural Protegida bajo la modalidad de Parque Estatal denominado “Manantial de la Media Luna”. Diario Oficial de San Luis Potosí. 7 de junio del 2003. Retrieved on May 12th, 2019 from: www.segam.gob.mx

Soto-Galera, E., Mejía-Guerrero, O., & Pérez-Miranda, F. (2019). Herichthys labridens. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019: e.T192897A2179729. Retrieved on 04 December 2023 from: http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-2.RLTS.T192897A2179729

Straškraba, M. (1974). Seasonal cycle of the depth distribution of fish in the Klıcava Reservoir. Czech Journal of Animal Sciences, 19, 656–660.

Thrush, S., Dayton, P., Cattaneo-Vietti, R., Chiantore, M., Cummings, V., Andrew, N. et al. (2006). Broad-scale factors influencing the biodiversity of coastal benthic communities of the Ross Sea. Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 53, 959–971. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr2.2006.02.006

Torres-Orozco, R. E., & Pérez-Hernández, M. A. (2011). Los peces de México: una riqueza amenazada. Revista Digital Universitaria, 12, 1–15.

Wan, H. Y., Cushman, S. A., & Ganey, J. L. (2019). Improving habitat and connectivity model predictions with multi-scale resource selection functions from two geographic areas. Landscape Ecology, 34, 503–519. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-019-00788-w

Wiersema, J. H., Novelo, A. R., & Bonilla-Barbosa, J. R. (2008). Taxonomy and typification of Nymphaea ampla (Salisb.) DC. sensu lato (Nymphaeaceae). Taxon, 57, 967–974. https://doi.org/10.1002/tax.573025

Zeller, K. A., McGarigal, K., & Whiteley, A. R. (2012). Estimating landscape resistance to movement: a review. Landscape Ecology, 27, 777–797. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-012-9737-0