Sergio I. Salazar-Vallejo a, *, Patricia Salazar-Silva b

a El Colegio de la Frontera Sur, Depto. Sistemática y Ecología Acuática, Unidad Chetumal, Ave. Centenario Km 5.5, 77014 Chetumal, Quintana Roo, Mexico

b Tecnológico Nacional de México, Instituto Tecnológico de Bahía de Banderas, Crucero a Punta de Mita, 63734 Bahía de Banderas, Nayarit, Mexico

*Corresponding author: ssalazar@ecosur.mx (S.I. Salazar-Vallejo)

Abstract

To clarify the differences between Lepidasthenia Malmgren, 1867 and Lepidametria Webster, 1879, specimens of their type species are redescribed and illustrated. Diagnoses for both genera, a key to species of Lepidasthenia with giant neurochaetae, and a key to species of Lepidametria are included. Lepidasthenia elegans (Grube, 1840), described from the Gulf of Naples, has blocks of black segments alternating with a pale segment, posterior elytrigerous segments blackish; median and posterior segments with elytra every third segment; parapodia without notochaetae; neuropodia with neuropodial pre- and postchaetal lobes with margin entire; median segments with upper single neurochaetae thin, 1-2 giant neurochaetae barely denticulate, and medium-width neurochaetae with tips unidentate (accessory denticle minute). Lepidasthenia digueti Gravier, 1905, described from the Gulf of California living with balanoglossid hemichordates, is redescribed and reinstated. Lepidametria commensalis Webster, 1879, described living with terebellid polychaetes in Virginia, USA, has a brownish transverse segmental band along body; median segments with elytra alternating with dorsal cirri, posterior segments with series of 3-4 elytrigerous interrupted by 1 cirrigerous segment; parapodia with notochaetae; neuropodia elongate with neuropodial prechaetal lobe with upper area lobate, lower one entire, post-chaetal lobe entire; neurochaetae bidentate, median segments with giant neurochaetae barely denticulate.

Keywords: Type-species; Variation; Giant neurochaetae; Prechaetal lobes

Redescripciones de Lepidasthenia elegans, L. digueti y Lepidametria commensalis (Polychaeta: Polynoidae)

Resumen

Para aclarar las diferencias entre Lepidasthenia Malmgren, 1867 y Lepidametria Webster, 1879, ejemplares de sus especies tipo fueron descritas e ilustradas. Se incluyen diagnosis para ambos géneros, una clave para especies de Lepidasthenia con neurosetas gigantes y una clave para especies de Lepidametria. Lepidasthenia elegans (Grube, 1840), descrita del golfo de Nápoles, tiene bloques negros alternantes con un segmento pálido, elitrígeros posteriores negros; segmentos medios y posteriores con élitros cada tercer segmento; parápodos sin notosetas; neurópodos con lóbulos pre- y postsetales enteros; segmentos medios con neurosetas superiores delgadas, 1-2 neurosetas gigantes apenas denticuladas y neurosetas de grosor medio unidentadas (dentículo accesorio diminuto). Lepidasthenia digueti Gravier, 1905, descrita del golfo de California asociada con balanoglósidos, es redescrita y restablecida. Lepidametria commensalis Webster, 1879, descrita asociada con poliquetos terebélidos en Virginia, EUA, tiene una banda parduzca transversa segmentaria a lo largo del cuerpo; segmentos medios con élitros y cirros alternantes, segmentos posteriores con series de 3-4 elitrígeros y 1 cirrígero; parápodos con notosetas; neurópodos alargados con lógulo presetal con área superior lobulada, inferior entera, lóbulo postsetal entero; neurosetas bidentadas, segmentos medios con neurosetas gigantes apenas denticuladas.

Palabras clave: Especie-tipo; Variación; Neurosetas gigantes; Lóbulos presetales

Introduction

Lepidasthenia Malmgren, 1867, and Lepidametria Webster, 1879 are 2 genera of long-bodied polynoids whose species are commonly found living with other marine invertebrates. Malmgren (1867: 15) added the Greek suffix asthenia which comes from asthenes, meaning “without strength, weak” (Brown, 1954: 348) to emphasize the reduction of elytral size along body. Malmgren (1867: 16) only included Polynoe elegans Grube, 1840, described from the Adriatic Sea, such that it became the type by monotypy. From the original description (Grube, 1840: 85), this species had 2 patterns of sequences for the presence of cirri and elytra: they alternate along anterior and median chaetigers, and from segment 22 or 24, elytra are present singly, and 2 successive segments carry cirri. Malmgren (1867: 15) included the lack of notochaetae, the presence of minute elytra along median and posterior chatigers, and the pattern 2 segments with cirri, one with elytra in median and posterior chaetigers.

Webster (1879: 209-210) proposed Lepidametria, with Lepidametria commensalis from Virginia, USA, as its only species, and diagnosed it by including the presence of notochaetae, elytra not large enough as to cover dorsum, and elytra irregularly arranged in posterior segments. He gave no etymology, but the suffix ametria could be formed by uniting the Greek word metrios, meaning “within measure” (Brown, 521), with the Greek prefix a– meaning “not, without, negative, privative” (Brown, 1954: 62) for indicating the lack of regularity in the elytral pattern along posterior segments. Webster (1879: 210) also noted that Lepidametria differs from Lepidasthenia “by having setae in the dorsal rami”.

Chamberlin (1919: 38) separated the above genera by regarding Lepidasthenia as having elytra in pairs throughout the body, and Lepidametria with some segments having elytra on one side and a cirrus on the other, and he did not include the different sequence of cirri-elytra, or the presence of notochaetae. Seidler (1924: 16) keyed them out after the presence of notochaetae in Lepidametria, and the lack of them in Lepidasthenia (Gardiner, 1976: 85).

Day (1967: 88) regarded Lepidametria as a junior synonym of Lepidasthenia, but later he changed his mind (Day, 1973: 6). The synonymy, however, had been proposed by Gravier (1905b), Potts (1910), Fauvel (1917), and Hartman (1959: 85) but not by Pettibone (1963: 19).

Pettibone (1989) used the above features, together with the type of parapodia, and elytra for proposing a new subfamily, Lepidastheniinae, and did not include Lepidametria. Consequently, Lepidasthenia and Lepidametria are currently regarded as distinct and different enough, such that they belong to different subfamilies, and there are keys to genera available (Barnich & Fiege, 2004; Salazar-Vallejo et al., 2015). However, the type species of these 2 genera have not been redescribed, and by clarifying their morphological features the affinities of the species in each genus can be clarified, especially because different authors followed the synonymy, whereas others rejected it. These genera differ in the number of species they include; there are 4 species in Lepidametria (Read & Fauchald, 2024a), and over 40 in Lepidasthenia (Read & Fauchald, 2024b).

Materials and methods

During a research visit to the National Museum of Natural History (USNM), Smithsonian Institution, we had the opportunity to study the type material of L. commensalis Webster, 1879, and topotype specimens of L. elegans (Grube, 1840). This completed the previous study of other type specimens in the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris, France (MNHN), such that now we can provide their redescriptions.

The material is deposited in the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris, France (MNHN), and in the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., USA (USNM). Specimens were observed with standard stereo —and compound microscopes; sometimes, some body parts were immersed in Methyl green or Shirlastain-A for increasing the visibility of some morphological features, and this explains their greenish or orange to reddish color in some photos. A series of digital photos in successive focal plains were made for every object; the series of photos were optimized with HeliconFocus and plates were prepared with PaintShop Pro.

Results

Polynoidae Kinberg, 1856

Lepidastheniinae Pettibone, 1989

Lepidasthenia Malmgren, 1867

Type species. Polynoe elegans Grube, 1840, by monotypy.

Diagnosis (after Salazar-Vallejo et al., 2015). Lepidastheniinae with a long body of up to 150 segments. Elytra small, not covering each other, leaving dorsal region mostly uncovered; posterior region with one pair of elytra every 3 segments. Each elytron rounded, margins entire, without tubercles, pale or pigmented. Tentaculophores without chaetae. Notopodia reduced, without notochaetae. Neuropodia projecting with several types of neurochaetae. Ventral surface usually smooth.

Remarks

A key to genera of Lepidastheniinae is available elsewhere (Salazar-Vallejo et al., 2015). Lepidasthenia Malmgren, 1867 resembles Alentiana Hartman, 1942 and Telolepidasthenia Augener & Pettibone in Petibone, 1970 because they have short elytrophores, not transformed into peduncles. However, Lepidasthenia differs by having tiny, non-overlapping elytra in median segments, whereas the 2 other genera have large overlapping elytra in the same body region. Within Lepidasthenia, the presence of giant neurochaetae can separate species into 2 groups; the first group includes those species having giant neurochaetae, including L. elegans, and the larger group includes those species deprived of giant neurochaetae.

Key to species of Lepidasthenia Malmgren, 1867 with giant neurochaetae

(modified after Salazar-Vallejo et al., 2015)

1 Anterior eyes larger than posterior ones …………………………………………………… 2

– Anterior eyes smaller or subequal to posterior ones …………………………………………………… 4

2(1) Dorsal cirri subdistally swollen; ventral cirri digitate …………………………………………………… 3

– Dorsal cirri tapered; ventral cirri basally swollen, tapered …………………………………………………… L. ornata Treadwell, 1937, Western Mexico

3(2) First elytra with innervation …………………………………………………… L. elegans (Grube, 1840), Mediterranean Sea

– First elytra without innervation…………………………………………………… L. izukai Imajima & Hartman, 1964 Japan

4(1) Dorsal cirri subdistally swollen; ventral cirri tapered, surpassing neurochaetal lobe tip; neuraciculae falcate…………………………………………………… L. esbelta Amaral & Nonato, 1982, Brazil

– Dorsal and ventral cirri tapered, ventral cirri short, not reaching neurochaetal lobe tip…………………………………………………… 5

5(4) Palps 2 times as long as lateral antennae; giant neurochaetae unidentate…………………………………………………… L. loboi Salazar-Vallejo, González & Salazar-Silva, 2015 Patagonia

– Palps slightly longer than lateral antennae; giant neurochaetae uni- and bidentate ……………………………………………………L. nuda (Grube, 1870) Red Sea

Lepidasthenia elegans (Grube, 1840)

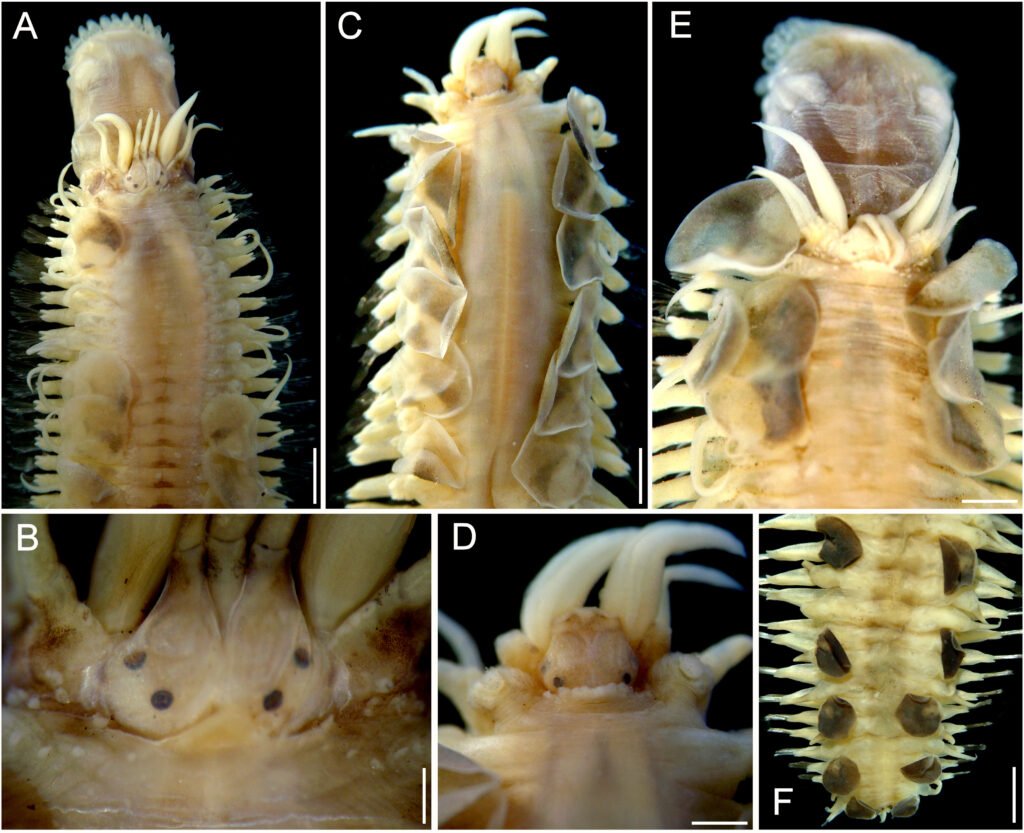

Fig. 1

Polynoe elegans Grube, 1840: 85.

Polynoe lamprophthalma von Marenzeller, 1874: 408, Pl. 1, Fig. 1.

Lepidasthenia elegans: von Marenzeller, 1876: 139-141 (syn.); Benham, 1901: 293 (pigm. pattern); Fauvel, 1923: 88, Fig. 33a-g (syn.); Seidler, 1924: 161-162; Barnich & Fiege, 2003: 88-90, Fig. 46; Núñez et al., 2015: 169-170, Fig. 69.

Diagnosis. Lepidasthenia with nuchal lappet smooth; anterior elytra with branching venation, median and posterior elytra minute, transparent; neurochaetae bidentate, including giant barely denticulate, and smaller clearly denticulate ones in median chaetigers; ventral surface of neuropodia smooth.

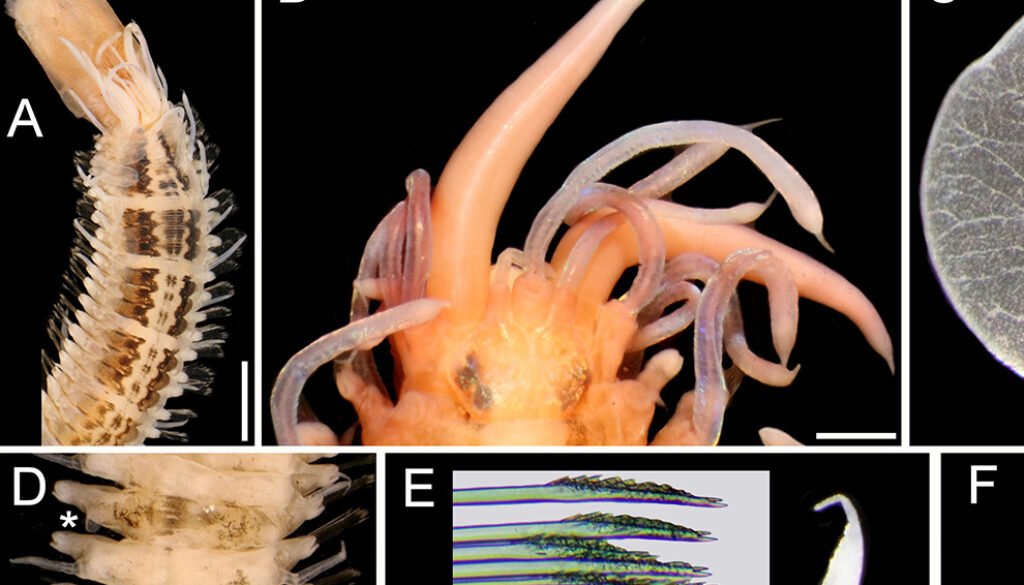

Figure 1. Lepidasthenia elegans (Grube, 1840), non-type specimens (USNM 47901). A, Largest specimen, anterior region, dorsal view; B, second largest specimen, anterior end, dorsal view; C, same, right elytron 2, seen from above; D, largest specimen, posterior region, dorsal view (*: elytra); E, same, chaetiger 10, left parapodium, anterior view (inset: tips of median neurochaetae); F, chaetiger 40, left parapodium, anterior view (inset: superior neurochaetae). Scale bars: A, 3 mm; B, 0.6 mm; C, 0.2 mm; D, 1.1 mm; E, F, 0.3 mm.

Description. Largest non-type specimen (USNM 47901) with body depressed, twisted; dorsum with 3 black longitudinal wide bands progressively paler, forming distinct blocks separated by a white segment, median band narrowest, often discontinuous (Fig. 1A); first block along chaetigers 2-7, then one segment pale, continued with blocks made of 3-4 segments, interrupted by a single pale segment, such that there are 4 blocks of 3 pigmented segments, followed by one with 4 segments, and then median and posterior regions with elytrigerous segments darker, followed by 2 paler cirrigerous segments. Venter pale, blackish along base of parapodia. Cephalic appendages and dorsal cirri white; elytra transparent. Pharynx fully exposed, brownish, 11 pairs of terminal papillae, transparent, some with a blackish core; 2 midlateral round papillae, behind terminal ones. Second largest specimen with pharynx not exposed; anterior elytra, and left parapodia of chaetigers 10 and 40 removed for observation (kept in container).

Prostomium bilobed, sub-hexagonal, slightly wider than long, facial tubercle not visible dorsally, globose. Eyes black, anterior eyes about 2 times as large as posterior ones, in widest prostomial area, directed laterally; posterior eyes close to posterior margin (Fig. 1B); in 3 specimens eyes enlarged, almost fused laterally. Median antenna slightly longer than right lateral one (left one in regeneration), ceratophore slightly wider than laterals; lateral antennae on prostomial anterior extensions; all ceratostyles cylindrical, mucronate. Palps massive, non-papillate, almost as long as median antenna, mucronate.

Tentacular segment not visible dorsally: tentaculophores long, cirrostyles wide, 3-4 times as long as prostomium; without chaetae. Segment 2 without nuchal lappet; first pair of parapodia and elytrophores directed anteriorly; ventral cirri 5-6 times as long as following ones (3-4 times in smallest specimen); elytrophores short anteriorly, minute along median and posterior rergions.

Elytra 30 pairs (22 in smallest specimen), smooth, without fimbriae, progressively smaller in median and posterior chaetigers; first 13(11) pairs alternating with cirrigerous segments, then present every third segment. First elytra with distinct branching venation from insertion area (Fig. 1C), posterior elytra minute slightly larger than elytrophore (Fig. 1D).

Parapodia sequiramous. Dorsal cirri with cirrophore short, cylindrical along anterior chaetigers, inserted basally (Fig. 1E), truncate conical in posterior chaetigers (Fig. 1F), terete, mucronate, surpassing neurochaetal tips. Notopodium short, round, without chaetae. Neuropodium with pre- and postchaetal lobes of similar size, both with margins smooth, without acicular lobes. Ventral cirri tapered, short, inserted basally. Nephridial lobes from segment 12, digitate.

Anterior chaetigers with neurochaetae barely swollen subdistally (Fig. 1E), pectinate area with petaloid spines, tips bidentate, accessory tooth almost as large as main one (Fig. 1E, inset). Posterior chaetigers with neurochaetae less spinous, of 3 types, superior neurochaetae thin, spinous superior giant neurochaetae darker with tips bidentate or unidentate, and thinner bidentate neurochaetae (Fig. 1F, inset).

Posterior region tapered; pygidium with anus terminal, with 2 small, lateral anal cirri (Fig. 1D.

Variation. Pigmentation pattern fades off in older specimens. Anterior eyes are usually 2 times as large as posterior ones, but they are laterally nearly fused in some specimens, but not in all. The sequence of elytrigerous and cirrigerous segments is constant; first 11-13 elytra alternate with cirri, following ones are in a sequence with one elytron and 2 dorsal cirri, to end of body.

Taxonomic summary

Type material. Polynoe elegans Grube, 1840; 2 syntypes (ZMB 17) from Sicily, 4 syntypes (ZMB 1176) from Palermo, and 2 syntypes (ZMB 1177) from unspecified Mediterranean localities, plus several other specimens in the same museum (Lesina: ZMB 1172; Luisin piccolo: 1173; and Cherso: 1174, 1175); pigmentation faded off.

Additional material. Three specimens (USNM 5144), Bay of Naples, Italy, 1893, purchased from Stazione Zoologica, Napoli (complete, barely pigmented, better defined in smallest specimen; some parapodia and elytra previously removed (kept in container); eyes better defined in one specimen, anterior eyes about 2 times as large as posterior ones; body 37-80 mm long, 4.5-8.5 mm wide, 65-82 chaetigers). Five specimens (USNM 47900), The Maire, Marseille, France, rocky bottom, 9 Apr. 1971, H. Zibrowius, coll. (3 complete; dorsal pigmentation pattern blackish to brownish, one with pharynx partially exposed, with 4 additional papillae, 2 basal to terminal ones, 2 others irregular; chaetigers 2-7 forming a continuous block, then blocks of mostly 3 segments interrupted by a pale segment anteriorly; one with diffuse pigmentation along medial and posterior regions, 2 others with elytrigerous segments darker than paler cirrigerous ones; anterior eyes 2 times as large as posterior ones, not fused laterally; posterior segments of larger specimens with a white mass inside basal dorsal cirri; body 50-70 mm long, 7.0-7.5 mm wide, 85-94 chaetigers). Four specimens (USNM 47901), Cap l’Abeille. 2 km south of Banyuls, France, corals, 30 m, 6 May 1967, M.H. Pettibone and L. Laubier, coll. (3 complete; body 27.5-50.5 mm long, 4.5-6.5 mm wide, 57-72 chaetigers; used for redescription).

Distribution. Mediterranean Sea, in shallow water coralligenous or rocky bottoms.

Remarks

Hartwich (1993: 96) listed several lots in Berlin and regarded them almost all as syntypes. After the study of many types of species described by Grube, we anticipate his type and non-type specimens should be colorless by now, and this explains why we selected one specimen with bright pigmentation for redescribing the species. The pigmentation pattern was clearly illustrated by Benham (1901: 293), and this is rather consistent in specimens from the Mediterranean Sea. Lepidasthenia elegans (Grube, 1840) has been reported from the Indian Ocean (Day, 1967; Potts, 1910), but those specimens differ in several features from the Mediterranean ones, such as the position of the anterior eyes, the type of dorsal and ventral cirri, and the shape of the giant neurochaetae. These records might belong in L. nuda (Grube, 1870), redescribed by Wehe (2006: 73), which could include L. affinis Horst, 1917.

Hartman (1959: 99) regarded Polynoe blainvillii Audouin & Milne Edwards, 1834 as a synonym of L. elegans (Grube, 1840). However, this publication is the compilation of some earlier publications, and the original proposal was P. blainvillii Audouin & Milne Edwards, 1832. Audouin and Milne-Edwards (1832: 430-431; 1834: 94-95) proposed the new name for a specimen briefly described and illustrated by de Blainville (1828: 459, Pl. 10, Fig. 2), but without locality, and identified as Eumolpe scolopendrina Savigny, 1822. The French specialists noted the differences with P. scolopendrina Savigny, 1822 such as having reduced elytra to the posterior end (larger, but missing in posterior region in P. scolopendrina). Regretfully, probably because it was identified as an already known species, de Blainville provided no morphological details in the description but in his illustrations (2: whole body, dorsal view; 2a: parapodium) the parapodium was depicted with notochaetae. As indicated above, notochaetae are missing in Lepidasthenia species, and if P. blainvillii is a Lepidasthenia, this could be an erroneous observation. The de Blainville specimen was not deposited, such that there is no means to clarify this potential synonymy.

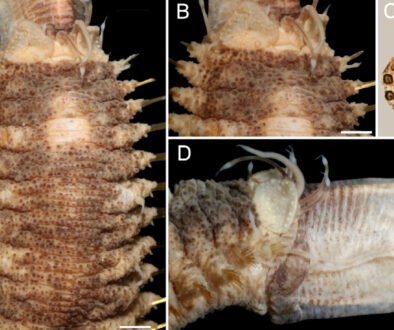

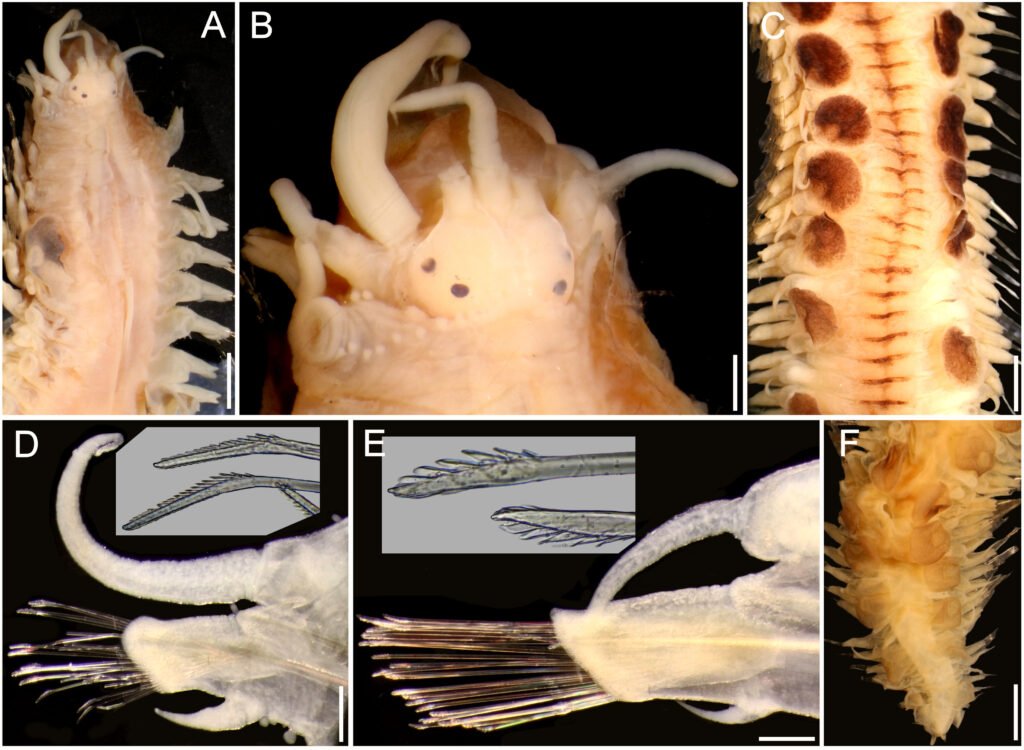

Figure 2. Lepidasthenia digueti Gravier, 1905, reinstated, syntypes (MNHN POLY TYPE). A, syntype 119, anterior region, dorsal view; B, same, close-up of anterior end; C, syntype MNHN POLY TYPE 120, anterior region, dorsal view; D, same, close-up of anterior end; E, syntype 119b, anterior region, dorsal view; F, same, posterior region, dorsal view. Scale bars: A, 1.5 mm; B, 0.1 mm; C, 1.7 mm; D, 0.7 mm; E, 1 mm; F, 1.3 mm.

Nevertheless, if P. scolopendrina sensu de Blainville, or P. blainvilli are ever recorded, they should not be retained as senior synonyms of P. elegans Grube, 1840. If they are found, it might be better to regard P. blainvilli as a nomen oblitum, and P. elegans would be a nomen protectum (ICZN 1999, Art. 23.9).

Lepidasthenia digueti Gravier, 1905, reinstated

Lepidasthenia digueti Gravier, 1905a: 177-181; 1905c: 160-173, Textfigs 1-9; Fauvel, 1943: 4-5; Salazar-Silva, 2006: 150.

Diagnosis. Lepidasthenia with nuchal lappet crenate: median and posterior elytra slightly smaller than anterior ones, brown to blackish, non-transparent; neurochaetae unidentate, without giant chaetae.

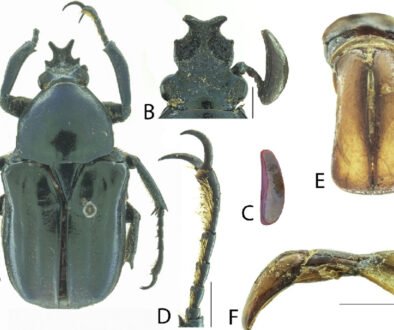

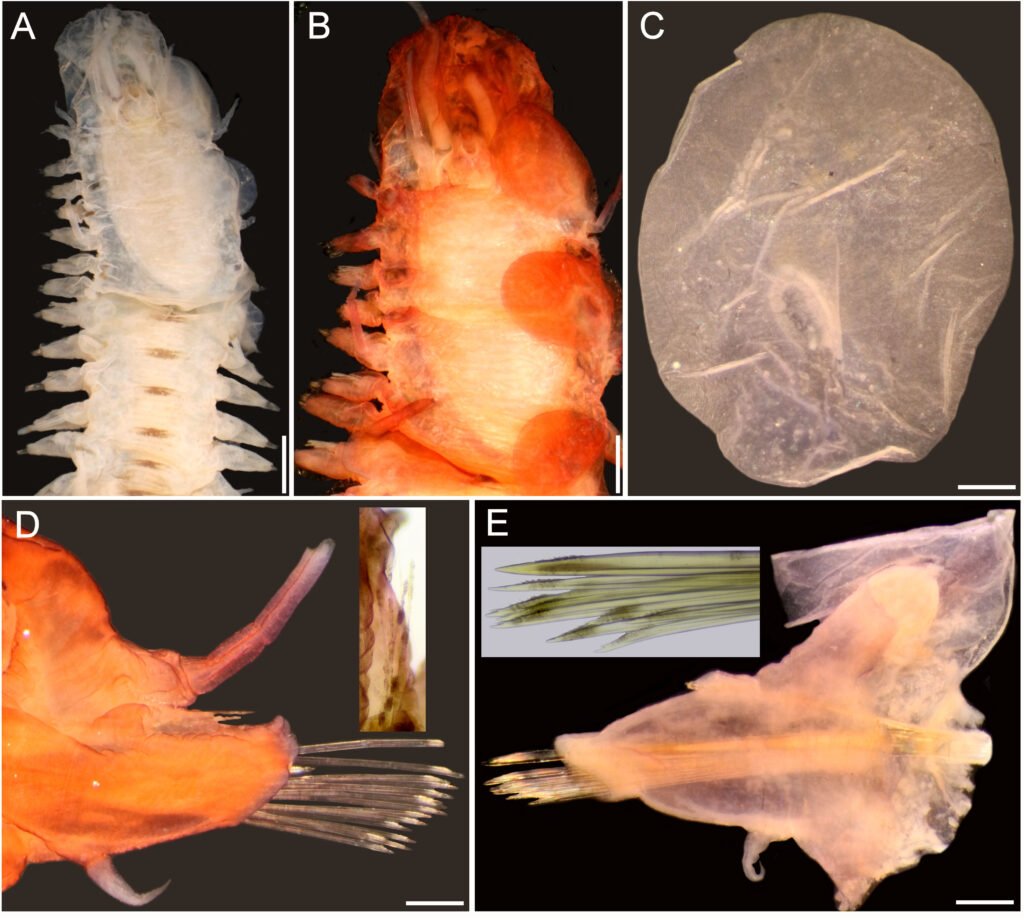

Description. Syntypes (MNHN POLY TYPE 119, 120; USNM 51613) in poor condition, fragmented, with grayish pigmentation on ceratophores, tentaculophores and on elytral surface (Fig. 2A, C, E), anterior pigmentation faded off in another syntype (USNM 51613) (Fig. 3A); body with small blackish spots dorsally on anterior segments, darker along posterior segments.

Prostomium bilobed, wider than long; facial tubercle reduced. Two pairs of eyes, dark, rounded, of similar size, anterior eyes on widest prostomial area, dorsolateral, posterior eyes dorsal, near posterior prostomial margin (Figs. 2B, D, 3B). Median antenna with ceratophore thin, short, grayish, inserted frontally between prostomial lobes, ceratostyle thick, long, tapering in filiform tip, slightly longer than lateral ceratostyles. Lateral antennae with ceratophores thick, short, grayish, inserted terminally, ceratostyles thinner, long, taper in filiform tip. Palps thin, pale, long, tapered, tip filiform, surface smooth, non-papillate. Pharynx fully exposed in one syntype (MNHN POLY TYPE 119) (Fig. 2A), brownish, with 14 pairs of terminal papillae, and 2 subdistal lateral low tubercles.

Tentacular segment not visible dorsally. Tentaculophores, thick, short, without chaetae, not covered by elytrophores, tentacular cirri long, as long as antennae but thinner. Second segment projected on prostomium as a short nuchal lobe, margin crenate. First pair of elytrophores not expanded dorsally, with some scattered papillae.

Numerous elytra (number indeterminate due to condition of specimens); first elytra present in one syntype (Fig. 2E), slightly larger than following ones, apparently not completely covering anterior end; after pair 12 alternate with 2 dorsal cirri, on the posterior segments elytra alternate with 2 or 3 dorsal cirri. Elytra small, not overlapped middorsal, covering 2 adjacent segments. Elytral margins smooth, without fimbriae; anterior elytra surface with brown area diffuse mainly toward mid-dorsal line, posterior elytra with homogeneous pigmentation.

Parapodia biramous. Notopodia reduced to small lobes. Neuropodia long, thin, with prechaetal and postchaetal lobes rounded, of similar size. Dorsal tubercles absent, elytrophores small, rounded, not directed dorally. Dorsal cirri pale, smooth, cirrophores short, slightly swollen. Ventral cirri long, thick, tapered in filiform tip, cirrophore short, thick. Anterior segments with neuropodia with 3-4 fungiform ventral papilla (Fig. 3D); median and posterior chaetigers with neuropodia ventrally smooth (Fig. 3E). Nephridial papillae from segment 10.

Notochaetae absent. Neurochaetae with pectinate area variably modified along bundle; anterior chaetigers with lower neurochaetae with longer pectinate area (Fig. 3D, inset); median and posterior chaetigers with neurochaetal pectinate area decreasing in size ventrally (Fig. 3E, inset); pectinate area with series of long, petaloid spines; tips bidentate, main tooth short, accessory denticle shorter, almost completely fused to main tooth. No giant neurochaetae present.

Posterior region tapered (Figs 2F, 3F); pygidium with anus terminal, anal cirri short, ventral.

Taxonomic summary

Type material. Syntypes of Lepidasthenia digueti Gravier, 1905 (MNHN POLY TYPE 119, 120; USNM 51613), La Paz, Baja California, Gulf of California, México, 1904, L. Diguet, coll.

Distribution. Only known from the Gulf of California, associated with an unidentified, intertidal balanoglossid hemichordate.

Remarks

Lepidasthenia digueti Gravier, 1905 is easily recognized as belonging to Lepidasthenia since the original description after the sequence of elytra in posterior segments being present every third segment, the lack of notochaetae, and the elongate neuropodial lobes. This is confirmed despite the fragmented condition of the type specimens. The crenate nuchal hood is very distinctive, although this was not included in the original description, together with the sequence of elytra and cirri along median segments.

The syntype specimens are all fragments, as originally indicated by Gravier (1905a: 179, 1905c: 163), but they include both body ends, and their features correspond to Lepidasthenia. After the type of sequence of elytra-dorsal cirri along median and posterior regions, and after the presence of apparently unidentate neurochaetae (accessory denticle minute), we confirm it belonging in Lepidasthenia. Lepidasthenia digueti belongs in the group of species having apparently unidentate neurochaetae, without giant chaetae, and without ventral papillae along neuropodial surface.

Solís-Weiss et al. (2004: S14) hesitated about the type status of the Paris Museum specimens, probably because they were fragments; we confirm the 2 Paris specimens and the one in Washington are all syntypes. It is enigmatic, however, how a syntype was sent to Washington; there are no indications in the catalogue card for the specimen about how it reached Washington, and it is likely that Dr. Marian Pettibone, after her long-time involvement with polynoid polychaetes, received it as a donation from the Paris museum.

Read and Fauchald (2024a) have listed L. digueti in Lepidametria after Seidler (1923). This confusion has 2 explanations. First, Gravier (1905a: 180; 1905b: 166) indicated there was a non-exposed notopodial compact bundle of chaetae, but after the study of type specimens, Fauvel (1943: 4) explained they were fibers inserted close to acicular tips, and confirmed L. digueti was a true Lepidasthenia after the lack of notochaetae, but this conclusion was overlooked. Second, Seidler (1923: 258) studied one specimen from Charlestown, and he indicated the locality was in the Pacific coast of Central America. This is wrong. Charlestown is the capital of Nevis Island, in the archipelago of Saint-Kitts and Nevis, in the Caribbean Sea. His specimen might belong to a likely undescribed, western Atlantic species of Lepidametria.We think it is incorrect to incorporate an eastern Pacific species from one genus, into any other on the basis of specimens from a very different ocean basin, or without the study of type material.

Figure 3. Lepidasthenia digueti Gravier, 1905, reinstated, syntype (USNM 51613). A, Anterior region, dorsal view, first right parapodia previously removed; B, anterior end, dorsal view; C, median fragments, dorsal view; D, anterior chaetiger, right parapodium, anterior view (inset: lower neurochaetae tips); E, median chaetiger, right parapodium, anterior view (inset: median neurochaetae tips); F, posterior region, dorsal view. Scale bars: A, 1.3 mm; B, 0.4 mm; C, F, 1.6 mm; D, E, 0.3 mm.

The hemichordate was not described soon, as indicated by Gravier (1905a, c), and its identity remains unknown. The hemichordate could be Ptychodera flava Eschscholtz, 1825, a widely distributed species in the Indian and Pacific oceans (Uribe & Larrain, 1992).

Lepidonotinae Willey, 1902

Lepidametria Webster, 1879

Type species. Lepidametria commensalis Webster, 1879, by monotypy.

Diagnosis (after Salazar-Vallejo et al., 2015). Lepidonotinae with a long body with up to 80 segments. Elytrae large, covering body or leaving a narrow dorsal surface uncovered; posterior region with elytra and cirri alternating every other segment. Tentaculophores with chaetae. Notopodia reduced, with fine notochaetae at least along anterior and median segments, rarely absent. Neuropodia projecting with several types of neurochaetae. Ventral surface often papillated.

Remarks

As indicated by Pettibone (1953) and Salazar-Vallejo et al. (2015), Lepidametria differs from Lepidasthenia because it has notochaetae, and alternating elytra and cirri along median and posterior segments, whereas in Lepidasthenia there are no notochaetae, and elytra occur every third segment. The need for a redescription of the type material was indicated elsewhere (Salazar-Vallejo et al. 2015: 26). In a recent contribution (Salazar-Vallejo et al. 2015) we regarded Bouchiria Wesenberg-Lund, 1949, as a junior synonym of Lepidametria; it is a junior synonym but of Lepidasthenia, as indicated by Wehe (2006).

Read and Fauchald (2024) list 4 species in Lepidametria: L. brunnea Knox, 1960; L. commensalis, L. digueti (Gravier, 1905); and L. lactea (Treadwell, 1939). We have shown above that L. digueti belongs in Lepidasthenia, we regard L. brunnea as belonging in Lepidasthenia because it lacks notochaetae, and has elytra every 3 segments along posterior region, and we confirm Hartman (1951) synonymy of L. lactea with L. commensalis. Consequently, there would only be one species in Lepidametria (L. commensalis); however, we think that L. virens (Blanchard in Gay, 1849), and L. gigas (Johnson, 1897) also belong in this genus. A key to species is included below.

Lepidametria commensalis Webster, 1879

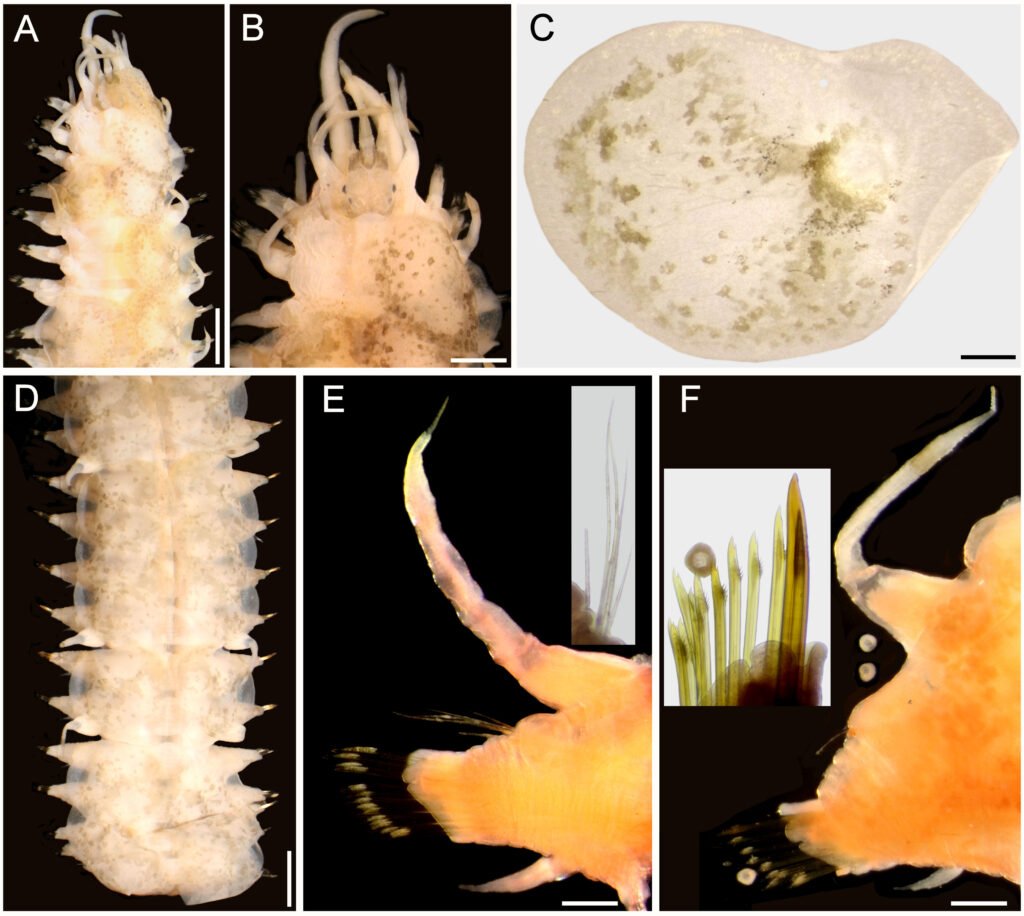

Figs. 4, 5

Lepidametria commensalis Webster, 1879: 209-212, Pl. 3, Figs. 23-31; Hartman, 1951: 17 (syn.); Pettibone, 1963: 19-20, Fig. 4k; Day, 1973: 6; Gardiner, 1976: 86-87, Fig. 1k-n.

Lepidasthenia lactea Treadwell, 1939: 3-5, Figs. 13-15.

Diagnosis. Lepidametria with nuchal lappet smooth: median and posterior elytra slightly smaller than anterior ones, with dark spots, non-transparent; neurochaetae uni- and bidentate, with giant chaetae in median chaetigers.

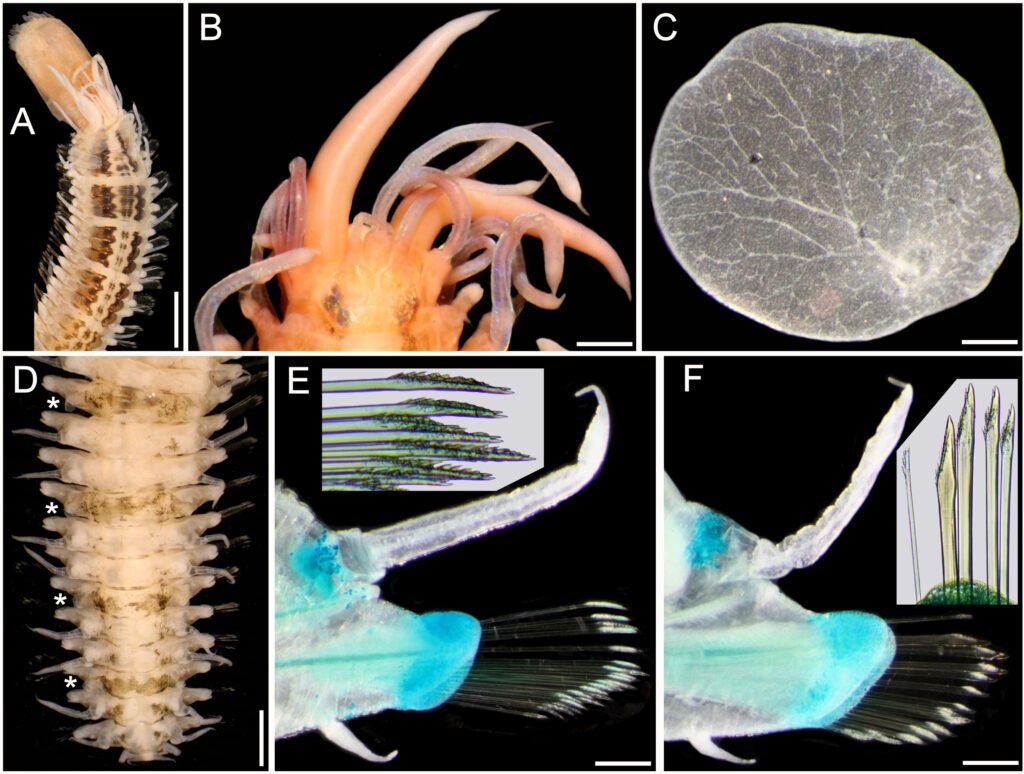

Description. Syntypes of Lepidametria comensalis (USNM 527) include one beheaded specimen, better preserved (probably used for original description), and a complete specimen; description based on the complete soft syntype. Some parapodia and elytra already dissected (kept in container); no further dissections to avoid additional damage.

Body long, depressed, variably damaged, 70 mm long, 6 mm wide, 71 segments, dorsum with diffuse brownish intersegmental bands (Fig. 4A) [paratype of L. lactea (USNM 20420) 20 mm long, 64 segments; holotype of L. lactea (AMNH 2565) with 50 mm long, 2 mm wide, 62 segments, 34 pairs of elytra].

Prostomium bilobed, longer than wide, without facial tubercle (Fig. 4B). Eyes blackish, visible dorsally, small; anterior eyes in widest prostomial area. Median antenna lost, ceratophore cylindrical, long. Lateral antennae lost, on prostomial anterior extensions, ceratophores as long as median one. Palps massive, long, with papillae, tapered into fine tips.

Tentacular segment not visible dorsally; tentaculophores long, cirrostyles wide, 2 times as long as prostomium. Segment 2 with nuchal lappet; first pairs of parapodia and elytrophores perpendicular, not directed anteriorly; ventral cirri about 2 times as long as following ones. Without dorsal tubercles; elytrophores short.

Elytra 44 pairs, subcircular, thin, transparent, smooth, without fimbriae (Fig. 4C), non-overlapping mid-dorsally, except posterior pair; after pair 12, most alternating with dorsal cirri; elytra pairs 12 and 13, and 14 and 15 contiguous (no dorsal cirri between them). Posterior region with elytra paired along 3-4 segments, then one elytrigerous, followed by one or 2-3 pairs of elytra.

Parapodia biramous, short, about as long as half body width (Fig. 4D). Dorsal cirri thick, short, not surpassing neuropodial tips, subdistally swollen, with long tips, with a brown band in widened area; cirrophore thick, short, swollen basally, inserted basally. Notopodia with notochaetae present along body, missing in far posterior chaetigers. Neuropodia with pre- and postchaetal lobes of similar size, prechaetal lobe lobulate along superior part, continuous along lower part, postchaetal lobe continuous, without acicular lobes. Ventral cirri short, thin, inserted medially in neuropodium. Nephridial lobes cylindrical, long, from segment 8.

Notochaetae scarce, smooth capillaries, not reaching neuropodial tips (Fig. 4D, inset). Neurochaetae most bidentate, a few unidentate, pectinate area slightly wider, rows of spines restricted to wider basal area. Median segments with a single giant unidentate neurochaeta, denticles minute (Fig. 4E, inset).

Posterior end tapered; anus terminal, anal cirri thin.

Variation. A smaller specimen (USNM 52842), mature female, has elytra overlapping completely along middorsum (Fig. 5A), transverse intersegmental bands visible. Prostomium pale, with ceratophores brownish (Fig. 5B); median antenna about 2 times as long as both prostomium and lateral antennae (left one in regeneration), ceratostyles barely swollen, darker than adjacent areas; palps thick, papillate, about 2 times as long as median antenna. Tentaculophores with cirrostyles slightly shorter than median antenna, right one with a single chaeta. Second segment with nuchal lappet.

Elytra oval, wider than long, with brown spots, including insertion areas (Fig. 5C). In posterior chaetigers, elytral sequence is 3 elytrigerous followed by one cirrigerous and then 3 other elytrigerous (Fig. 5D). Dorsal tubercles distinct in cirrigerous segments, at least along posterior region.

Figure 4. Lepidametria commensalis Webster, 1879, complete syntype (USNM 527). A, Anterior region, dorsal view; B, anterior end, dorsal view, after Shirlastain-A; C, elytron from unknown chaetiger, seen from above; D, cirrigerous parapodium from an unknown chaetiger, dorsal cirrus broken, after Shirlastain-A (inset: close-up of notochaetae); E, elytrigerous parapodium from an unknown chaetiger, elytron folded backwards, after Shirlastain-A (inset: neurochaetae). Scale bars: A, 1.3 mm; B, 1 mm; C-E, 0.3 mm.

Cirrigerous parapodia with dorsal cirri barely swollen subdistally, with brown band, with more abundant notochaetae along anterior region (Fig. 5E), neurochaetae of similar width; posterior parapodia with less notochaetae, and upper giant spine; neurochaetae mostly bidentate, progressively unidentate dorsally (Fig. 5F, inset). Oocytes about 100 µm in diameter.

Two other specimens, complete (USNM 52840, 52841) have elytra overlapping laterally, but leaving a narrow middorsal area uncovered; dorsum with complex pigmentation pattern: the transverse bands are clearly on the posterior part of each segment, not intersegmental, and there is a wide, oval brownish spot along most dorsal surface of each segment, although it can be interrupted medially by a paler area. One specimen (USNM 52841) with pharynx partially exposed, jaws are brownish, and there are 10 upper and 11 lower terminal papillae. Giant neurochaetae from second third of body (chaetigers 23 of 71; 25 of 70 in USNM 52840). One specimen (USNM 52840) with nephridial lobes globose, truncate, from chaetiger 8. Posterior region tapered, anus terminal, anal cirri resembling dorsal cirri.

Figure 5. Lepidametria commensalis Webster, 1879, non-type specimen (USNM 52842). A, Anterior region, dorsal view; B, anterior end, dorsal view; C, elytron 3 right, seen from above; D, posterior region, dorsal view; E, chaetiger 10, right parapodium, anterior view, after Shirlastain-A (inset: notochaetae); F, chaetiger 45, right parapodium, anterior view, after Shirlastain-A (inset: neurochaetae). Scale bars: A, 1.4 mm; B, 0.8 mm; C, E, F, 0.3 mm; D, 1.2 mm.

Another specimen (USNM 56533) rolled ventrally, elytra almost completely brownish, with pale spots in insertion area; posterior segments have 3 elytra in sequence.

Taxonomic summary

Type material. Two syntypes of Lepidametria commensalis (USNM 527), Virginia, USA, Sta. H458, H. E. Webster, coll. Holotype of Lepidasthenia lactea (AMNH 2565), Galveston, Texas, USA Paratype of L. lactea (USNM 20420), Galveston, Texas, USA, O. Sanders, coll.

Additional material. One specimen (USNM 52840), Banks Channel, Wrightsville Beach, North Carolina, intertidal, in Amphitrite ornata tube, Mar. 1973, S.L. Gardiner, coll. (complete, bent laterally, pharynx partially exposed; body 70 mm long, 5 mm wide, chaetigers). One specimen (USNM 52841), Banks Channel, Wrightsville Beach, North Carolina, intertidal, in Amphitrite ornata tube, 8 Mar. 1974, S.L. Gardiner, coll. (pigmentation pattern indicated in variation; body 50 mm long, 4.5 mm wide, 71 chaetigers). One specimen (USNM 52842), mature female, without posterior end, intracoastal waterway, Wrightsville Beach, North Carolina, intertidal, in Amphitrite ornata tube, 5 Apr. 1974, T. Fox, coll. (pale, with elytra mottled; right elytra 1 and 3, and right parapodia of chaetigers 10 and 45 removed for observation (kept in container); body 66 mm long, 5 mm wide, 66 chaetigers). One specimen (USNM 56533), York River, Virginia, 29 Jul. 1977 (markedly bent ventrally, 2 posterior parapodia and many elytra detached (30 elytra and 2 parapodia in container); not measured for avoiding further damage).

Distribution. Virginia to Texas, USA, in shallow waters, associated with terebellid polychaetes, and with sponges (Dauer 1973).

Remarks

Webster (1879: 211) indicated that the sequence of elytra and cirri was asymmetrical in posterior chaetigers, such that one elytron could be on side, and one dorsal cirri on the other side. This was confirmed in the beheaded syntype, but this is not present in the other non-type specimens. Bergström (1916) noted this same anomaly in other long-bodied polynoids, and it has been recently reported for another species (Salazar-Vallejo, 2024).

Hartman (1951) regarded Lepidasthenia lactea Treadwell, 1939 as a junior synonym of L. commensalis Webster, 1879. The type specimens of L. lactea have a similar shape of prostomium, and share the same type of elytra, noto- and neurochaetae, but they are smaller, such that the specimens might be juveniles.

Webster (1879) found L. commensalis living in tubes of the terebellid Amphitrite ornata (Leidy, 1855), and Hartman (1951) found it living with Thelepus setosus (de Quatrefages, 1866), whereas L. lactea was found in different, unidentified terebellid tubes.

Key to species of Lepidametria Webster, 1879

1 Median and posterior elytra regularly alternating with dorsal cirri …………………… 2

– Median and posterior elytra not regularly alternating …………………… L. virens (Blanchard in Gay, 1849) Chile

2(1) Elytra present along body …………………… L. commensalis Webster, 1879 Northwestern Atlantic

– Elytra not reaching posterior end …………………… L. gigas (Johnson, 1897) California

Acknowledgments

The generous support by curators and collection managers is deeply acknowledged. Karen Osborn and Karen Reed currently, Linda Ward, the late Kristian Fauchald, formerly (USNM), Fredrik Pleijel and Tarik Meziane (MNHN). They all were and have been very supportive of our research activities and provided lab space and facilities for this study. Anabel León-Hernández and Daniel Pech provided some publications. The careful reading by two anonymous referees helped us to improve this final contribution. In her usual high standards, María Antonieta Arizmendi kindly took care of all the formatting issues for this publication.

References

Amaral, A. C., & Nonato, E. F. (1982). Anelideos poliquetos da costa brasileira. Aphroditidae e Polynoidae. Brasilia: Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico.

Audouin, J. V., & Milne-Edwards, H. (1832). Classification des annélides, et description de celles qui habitent les côtes de la France. Annales des Sciences Naturelles, 27, 337–447.

Audouin, J. V., & Milne-Edwards, H. (1834). Recherches pour servir à l’histoire naturelle du littoral de la France, ou recueil de mémoires sur l’anatomie, la physiologie, la classification et les mœurs des animaux de nos côtes (Vol. 2, Pt. 1). Paris: Crochard.

Barnich, R., & Fiege, D. (2003). The Aphroditoidea (Annelida: Polychaeta) of the Mediterranean Sea. Abhandlungen der Senckenbergischen Naturforschenden Gesellschaft, 559, 1–170.

Barnich, R., & Fiege, D. (2004). Revision of the genus Lepidastheniella Monro, 1924 (Polychaeta: Polynoidae: Lepidastheniinae) with notes on the subfamily Lepidastheniinae and the description of a new species. Journal of Natural History, 38, 863–876. https://doi.org/10.1080/0022293021000046432

Benham, W. B. (1901). Polychaet worms. In S. F. Harmer & A. E. Shipley (Eds.), The Cambridge natural history (Vol. 2). London: Macmillan.

Bergström, E. (1916). Die Polynoiden der schwedischen Sudpolarexpedition 1901-1903. Zoologiska Bidrag från Uppsala, 4, 269–304.

Brown, R. W. (1954). Scientific words: a manual of methods and a lexicon of materials for the practice of logotechnics. Baltimore: George W. King.

Chamberlin, R. V. (1919). The Annelida Polychaeta [Albatross Expeditions]. Memoirs of the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard College, 48, 1–514.

Dauer, D. M. (1973). Polychaete fauna associated with Gulf of Mexico sponges. Florida Scientist, 36, 193–196.

Day, J. H. (1967). A monograph on the Polychaeta of South Africa. Part 1. Errantia (Vol. 656). London: British Museum (Natural History).

Day, J. H. (1973). New Polychaeta from Beaufort, with a key to all species recorded from North Carolina. NOAA Technical Report, National Marine Fisheries Services Circular, 375, 1–153.

De Blainville, H. M. D. (1828). Vers. Dictionnaire des Sciences Naturelles, 57, 365–625. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/25316888 [Atlas: https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/24394694]

De Quatrefages, A. (1866). Histoire naturelle des Annelés marins et d‘eau douce. Annélides et Géphyriens (Vol. 2). Paris: Librairie Encyclopédique de Roret.

Eschscholtz, F. (1825). Berich über die zoologisch Ausbeute der Reise von Kronstadt bis St. Peter und Paul. Isis von Oken, 1825.

Fauvel, P. (1917). Annélides polychètes de l’Australie méridionale. Archives de Zoologie Expérimentale et Générale, 56, 159–277. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/6322379

Fauvel, P. (1923). Polychètes errantes. Paris: Fédération Française des Sociétés de Sciences Naturelles.

Fauvel, P. (1943). Annélides polychètes de Californie. Mémoires du Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, nouvelle série, 18, 1–32. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/59784292

Gardiner, S. L. (1976). Errant polychaete annelids from North Carolina. Journal of the Elisha Mitchell Scientific Society, 91, 78–220.

Gay, C. (1849). Historia física y política de Chile, según documentos adquiridos en esta república durante doce años de residencia en ella. Zoología, Tomo 3, 9–52; Atlas 2, Pls. 1-3. Santiago: Museo de Historia Natural. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/16438163 [Atlas: https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/55213605]

Gravier, C. (1905a). Sur un Polynoidien (Lepidasthenia digueti nov. sp.) commensal d’un Balanoglosse de Basse-Californie. Bulletin du Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris, 11, 177–184.

Gravier, C. (1905b). Sur les genres Lepidasthenia Malmgren et Lepidametria Webster. Bulletin du Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris, 11, 181–184.

Gravier, C. (1905c). Sur un polynoïden (Lepidasthenia digueti nov. sp.), commensal d’un balanoglosse de Basse-Californie. Bulletin de la Société Philomatique de Paris, neuvième série, 7, 160–173.

Grube, A. E. (1840). Actinien, Echinodermen und Würmer des Adriatischen- und Mittelmeers nach eigenen Sammlungen beschrieben. J.H. Bon, Königsberg. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/10662919

Grube, E. (1870). Bemerkungen über anneliden des Pariser Museums. Archiv für Naturgeschichte, Berlin, 36, 281–352.

Hartman, O. (1942). A review of the types of polychaetous annelids at the Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University. Bulletin of the Bingham Oceanographic Collection, Yale University, 8, 1–98.

Hartman, O. (1951). The littoral marine annelids of the Gulf of Mexico. Publications of the Institute of Marine Science, Port Aransas, Texas, 2, 7–124.

Hartman, O. (1959). Catalogue of the polychaetous annelids of the world (Occasional paper No. 23). Los Angeles: Allan Hancock Foundation Publications.

Hartwich, G. (1993). Die Polychaeten-Typen des Zoologischen Museums in Berlin. Mitteilungen aus der Zoologischen Sammlung des Museums für Naturkunde in Berlin, 69, 73–154.

Horst, R. R. (1917). Polychaeta Errantia of the Siboga Expedition. Part Ii Aphroditidae and Chrysopetalidae. Siboga Expeditie, 24, 46–143.

Imajima, M., & Hartman, O. (1964). The polychaetous annelids of Japan (Occasional paper No. 26). Los Angeles: Allan Hancock Foundation.

International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN). (1999). International Code of Zoological Nomenclature. Natural History Museum. https://code.iczn.org

Johnson, H. P. (1897). A preliminary account of the marine annelids of the Pacific Coast, with descriptions of new species. Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences, 1, 153–194.

Kinberg, J. G. H. (1856). Nya slägten och arter af Annelider. Öfversigt af Kongl. Vetenskaps-Akademiens Förhandlingar Stockholm, 12, 381–388.

Knox, G. A. (1960). Biological results of the Chatham Islands 1954 Expedition. Part 3. Polychaeta errantia. New Zealand Department of Scientific and Industrial Research Bulletin, 139, 77–143.

Leidy, J. (1855). Contributions towards a knowledge of the marine invertebrate fauna of the coasts of Rhode Island and New Jersey. Journal of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, 3, 135–152.

Malmgren, A. J. (1867). Annulata Polychaeta Spetsbergiæ, Grœnlandiæ, Islandiæ et Scandinaviæ. Hactenus cognita. Helsingforsiae, Ex Officina Frenckelliana.

Núñez, J., Barnich, R., Brito, M. C., & Fiege, D. (2015). Familias Aphroditidae, Polynoidae, Aceotidae, Sigalionidae y Pholoidae. Fauna Ibérica, 41, 89–257.

Núñez, J., Brito, M. C., & Ocaña, O. (1992). A new species of Lepidasthenia (Polychaeta: Polynoidae) from Canary Islands. Zoologica Scripta, 21, 347–349. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-6409.1992.tb00336.x

Pettibone, M. H. (1953). Some scale-bearing polychaetes of Puget Sound and adjacent waters. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press.

Pettibone, M. H. (1963). Marine polychaete worms of the New England region, 1. Families Aphroditidae through Trochochaetidae. Bulletin of the United States National Museum, 227, 1–356.

Pettibone, M. H. (1970). Polychaeta Errantia of the Siboga Expedition. Part IV. Some additional polychaetes of the Polynoidae, Hesionidae, Nereidae, Goniadidae, Eunicidae, and Onuphidae, selected as new species by the late Dr. Hermann Augener with remarks on other related species. Siboga-Expeditie Uitkomsten op Zoologisch, Botanisch, Oceanographisch en Geologisch Gebied verzameld in Nederlandsch Oost-Indië 1899–1900. Siboga – Expedition, 24, 199–270.

Pettibone, M. H. (1989). A new species of Benhamipolynoe (Polychaeta: Polynoidae: Lepidastheniinae) from Australia, associated with the unattached stylasterid coral Conopora adeta. Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington, 102, 300–304.

Potts, F. A. (1910). The Percy Sladen Trust Expedition to the Indian Ocean in 1905, under the leadership of Mr. J. Stanley Gardiner: 12. Polychaeta of the Indian Ocean, 2. The Palmyridae, Aphroditidae, Polynoidae, Acoetidae and Sigalionidae. Transactions of the Linnean Society of London, Series 2, Zoology, 16, 325–353.

Read, G., & Fauchald, K. (Eds.). (2024a). World polychaeta database. Lepidametria Webster, 1879. https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=236705 (Retrieved on August 20th, 2024).

Read, G., & Fauchald, K. (Eds.). (2024b). World polychaeta database. Lepidasthenia Malmgren, 1867. https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=129495 (Retrieved on August 20th, 2024).

Salazar-Silva, P. (2006). Scaleworms (Polychaeta: Polynoidae) from the Mexican Pacific and some other Eastern Pacific sites. Investigaciones Marinas, Valparaíso, 34, 143–161.

Salazar-Vallejo, S. I. (2024). Barnichia crialesae gen. nov., sp. nov., from the western Atlantic (Annelida, Polychaeta, Polynoidae, Polynoinae). Bulletin of Marine Science, 100, 439–449. https://doi.org/10.5343/bms.2023.0103

Salazar-Vallejo, S. I., González, N. E., & Salazar-Silva, P. (2015). Lepidasthenia loboi sp. n. from Puerto Madryn, Argentina (Polychaeta, Polynoidae). Zookeys, 546, 21–37. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.546.6175

Savigny, J. C. (1822). Système des annélides, principalement de celles des côtes de l’Égypte, et de la Sirie, offrant les caractères tant distinctifs que naturels des Ordres, Familles et Genres, avec la description des Espèces. Description de l’Égypte, Tome 1. Paris.

Seidler, H. J. (1923). Über neue und wenig bekannte Polychäten. Zoologischer Anzeiger, 61, 254–264.

Seidler, H. J. (1924). Beiträge zur Kenntnis der Polynoiden 1. Archiv für Naturgeschichte, 89, 1–217.

Solís-Weiss, V., Bertrand, Y., Helléouet, M. N., & Pleijel, F. (2004). Types of polychaetous annelids at the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Paris. Zoosystema, 26, 377–384.

Treadwell, A. L. (1937). The Templeton Crocker Expedition. 8. Polychaetous annelids from the west coast of Lower California, the Gulf of California and Clarion Island. Zoologica, Scientific Contributions of the New York Zoological Society, 22, 139–160.

Treadwell, A. L. (1939). New polychaetous annelids from New England, Texas and Puerto Rico. American Museum Novitates, 1023, 1–7.

Uribe, M. E., & Larraín, A. P. (1992). Estudios biológicos en el enteropneusto Ptychodera flava Eschscholtz, 1825 de Bahía Concepción, Chile. 1. Aspectos morfológicos y ecológicos. Gayana Zoología, 56, 141–180.

Von Marenzeller, E. (1874). Zur Kenntnis der adriatischen Anneliden. Sitzungsberichte der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftliche Classe, 69, 407–482.

Von Marenzeller, E. (1876). Zur Kenntniss der adriatischen Anneliden. Zweiter Beitrag. (Polynoinen, Hesioneen, Syllideen). Sitzungsberichte der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Wien, Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftliche Classe, 72, 129–171.

Webster, H. E. (1879). The Annelida Chaetopoda of the Virginian coast. Transactions of the Albany Institute, 9, 202–269.

Wehe, T. (2006). Revision of the scale worms (Polychaeta: Aphroditoidea) occurring in the seas surrounding the Arabian Peninsula. 1. Polynoidae. Fauna of Arabia, 22, 23–197.

Wesenberg-Lund, E. (1949). Polychaetes of the Iranian Gulf. Danish Scientific Investigations in Iran, 4, 247–400.

Willey, A. (1902). Polychaeta. In B. Sharpe, & J. Bell (Eds.), Report on the Collections of Natural History made in the Antarctic Regions during the Voyage of the “Southern Cross (pp. 262–283). London: British Museum.