Ensambles de macroalgas en diferentes zonas arrecifales de una playa urbana tropical en Brasil

Caio Ceza da Silva-Nunes a, c, d, e, *, Edilene Maria dos Santos Pestana b, c, Cibele Conceição dos Santos b, c, Lorena Pedreira Conceição a, c, José Marcos de Castro Nunes a, c

a Universidade Estadual de Feira de Santana, Departamento de Ciências Biológicas, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Botânica, Av. Transnordestina s/n, Novo Horizonte, CEP 44036-900, Feira de Santana, Bahia, Brazil

b Universidade Federal da Bahia, Instituto de Biologia, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Biodiversidade e Evolução, Rua Barão de Jeremoabo, 668 – Campus de Ondina, CEP: 40170-115, Salvador, Bahia, Brazil

c Universidade Federal da Bahia, Instituto de Biologia, Laboratório de Algas marinhas, Rua Barão de Jeremoabo, 668 – Campus de Ondina, CEP: 40170-115, Salvador, Bahia, Brazil

d Universidade Estadual do Sudoeste da Bahia, Departamento de Ciências Exatas e Naturais, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências Ambientais, Campus Universitário “Juvino Oliveira”, BR 415, Km 04 CEP: 45.700-000 Itapetinga, Bahia, Brazil

e Colégio Estadual de Tempo Integral Antônio Batista, Rua Presidente Vargas, 83 CEP: 46380-076 Candiba, Bahia, Brazil

*Corresponding author: caiobio08@gmail.com (C.C. da Silva-Nunes)

Received: 26 February 2025; accepted: 01 August 2025

Abstract

Marine macroalgae are commonly used as bioindicators because they are sensitive to environmental changes. This study aims to verify the composition of macroalgae in the intertidal region in 3 reef zones on Itapuã beach, located in Salvador-Bahia, Brazil and which presents high tourist activity. The samples were obtained in July 2017, in the intertidal zone, in 3 reef regions: Protected Region (PR), Tide Pool Region (TP) and Frontal Region (FR). In each zone, 3 transects (20 m each) were placed, in which 5 squares measuring 20 x 20 cm were arranged at random points. Additionally, individuals were collected around each transect for qualitative analysis. Dry biomass was measured, and statistical tests were carried out to obtain diversity, equitability and similarity data. Fifty-two taxa were identified, 27 Rhodophyta, 16 Chlorophyta and 9 Phaeophyceae. TP had the highest species richness (34) and diversity; however, no significant differences were found in macroalgal biomass between the 3 reef zones analyzed. This study contributes to the understanding of the composition and structure of phytobenthic communities in intertidal regions of the Bahian coast.

Keywords: Bahia; Bioindicator; Brazil; Phytobenthos

Resumen

Las macroalgas marinas se utilizan comúnmente como bioindicadores porque son sensibles a los cambios ambientales. Este estudio tiene como objetivo verificar la composición de macroalgas en la zona intermareal en 3 regiones arrecifales de la playa de Itapuã, ubicada en Salvador-Bahía, Brasil y que tiene alta actividad turística. Las muestras fueron obtenidas en julio de 2017, en la zona intermareal, en 3 regiones arrecifales: región posterior (PR), pozas de marea (TP) y región frontal (FR). En cada región, se colocaron 3 transectos (de 20 m cada uno), donde se distribuyeron aleatoriamente 5 cuadrantes de 20 x 20cm. Además, se recolectaron individuos alrededor de cada transecto para análisis cualitativo. Se midió la biomasa seca y se realizaron pruebas estadísticas para obtener datos de diversidad, equitabilidad y similitud. Se identificaron 52 taxones: 27 Rhodophyta, 16 Chlorophyta y 9 Phaeophyceae. La TP presentó la mayor riqueza de especies (34) y diversidad; sin embargo, no se encontraron diferencias significativas en la biomasa de macroalgas entre las 3 regiones arrecifales. Este estudio contribuye a la comprensión de la composición y estructura de las comunidades fitobentónicas en zonas intermareales del litoral bahiano.

Palabras clave: Bahia; Bioindicador; Brasil; Fitobentos

Introduction

The State of Bahia has the longest coastline in Brazil, 1,103 km showing a great diversity of environments: sandy beaches, coral reefs, sandstone formations, rocky shores and mangroves (Nunes & Paula, 2004a). Furthermore, it is a region that presents a great diversity of substrates and geographical features, which is reflected in the diversity of marine flora (Nunes, 2005b). Nunes and Paula (2002) divided reef formations into 3 zones: Frontal Region (FR), Protected Region (PR) and Tide Pool Region (TP). The FR is a very hydrodynamic region, where direct collision of waves occurs. The PR is the region before the lagoon and after the reef top, it may have pools and is a region protected from direct wave collision. The TP is deep and may suffer greater wave action, forming pools on the reef top, or may suffer less or no wave action, forming pools on the reef plateau.

In recent decades, coastal areas have been undergoing an intense process of urban development, which has caused significant environmental pressures and impacts, especially in benthic communities in reef formations (Costa et al., 2012; Nascimento, 2013). In Salvador, these impacts come from urban expansion, real estate speculation, tourism, human activities, such as fishing and trampling, causing the degradation of the flora and a reduction in the richness and diversity of species, especially in the composition and structure of algal communities.

Marine macroalgal communities have a great ecological role, being, together with microalgae, at the base of the food chain as primary producers, being a source of food for a large part of the marine fauna. The presence of macroalgae along the coast is responsible for softening the impact of waves on the sea coast, and also plays the role of habitat for other organisms, such as animals or as a substrate for algae (Nunes, 2010; Pedrine, 2013).

When these organisms are exposed to some human interference, they are sensitive to changes in their habitat, such as the increase in the concentration of organic matter in the water, which leads to an increase in the biomass of some algal groups, or even the depletion of some nutrient that causes the disappearance of a certain species, working as bioindicators of environmental quality. In addition, the degradation of this community’s structure favors the emergence and persistence of more resistant and opportunistic species, as well as the exclusion of more fragile species (Nascimento, 2013; Nunes, 2010).

Functional groups of algae are based on similarities in their morphological and anatomical characteristics, in addition to their ecological characteristics. Steneck and Dethier (1994) grouped algae into 7 categories, these being microalgae, filamentous, foliaceous, cylindrical-corticate, coriaceous, articulated calcareous and encrusting. In the model proposed by Steneck and Dethier (1994), it is highlighted that environments of high productivity and low disturbance present high biomass and diversity of morphofunctional groups, providing an abundance of coriaceous and cylindrical-cortical algae, as they have a relatively large size and a longer life cycle.

Knowledge about macroalgae on the coast of Bahia has been expanded through taxonomic studies, with the metropolitan area of Salvador being one of the main regions of the State’s coast studied, for example: Altamirano and Nunes (1997), Amorin et al. (2006), Barreto et al. (2004), Macedo et al. (2009), Marins et al. (2008), Nunes (1998a, b, 1999, 2005a, b), Nunes and Guimarães (2008, 2009, 2010), Nunes and Paula (2000, 2001, 2002, 2004a, b, 2006), Nunes et al. (2005).

Studies regarding the community structure of marine macroalgae have been carried out on the Brazilian coast. The majority are concentrated in the subtidal zone, namely, Amado Filho et al. (2003), Figueiredo et al. (2004), Villaça et al. (2010) in Rio de Janeiro, Oliveira-Carvalho et al. (2003) in Pernambuco, and Horta et al. (2008) in Santa Catarina. And in the intertidal zone, Barbosa et al. (2008) in Espírito Santo, and Muñoz and Pereira (1997) in Pernambuco. In Bahia, there are studies by Caires et al. (2013), Costa et al. (2012), and Ferreira et al. (2022), who carried out studies in the intertidal zone, and Costa Jr. et al. (2002) and Marins et al. (2008) in the subtidal zone. Although the coast of Bahia is the longest in Brazil, studies aimed to understand the structure of phytobenthic communities are scarce, creating a gap in the knowledge of these communities.

The present study analyzes the intertidal phytobenthic community in 3 reef zones of Itapuã beach, aiming to identify and compare differences in the composition and structure of the species between the studied areas, using the Feldmann and Cheney indices as bioindicators of local environmental characteristics.

Materials and methods

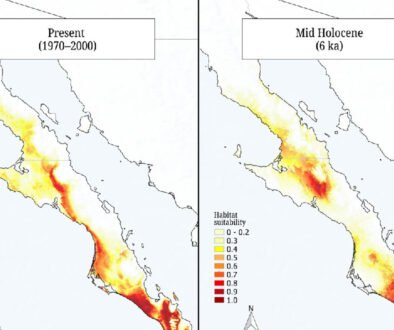

Itapuã beach is located in Salvador, Bahia in Brazil (Fig. 1), and corresponds to 2 large rocky bodies, and has coarse sand beaches, many reefs and rocky bollards (Nunes, 1998b). The collection was carried out on July 11, 2017, in the intertidal region, during low spring tide. The intertidal region was compartmentalized into the 3 regions proposed by Nunes and Paula (2002). Nunes (2010) was followed for the collection protocol.

Three 20 m transects were placed in each zone and arranged parallel to the coastline. In each transect, 5 squares measuring 20 x 20 cm were previously drawn. All material contained in the square was removed using a spatula. For qualitative analysis, specimens were collected around each transect. The collected material was placed in plastic bags or polyethylene bottles, fixed with 4% formalin. All material from the collections was taken to the Marine Algae Laboratory (LAMAR), at the Biology Institute of the Federal University of Bahia, where it was analyzed using a stereomicroscope (Leica© – Zoom 2000) to separate and identify the epiphytic algae.

Taxon identification was done using an Olympus© – CX 22 microscope. Blades were assembled from freehand cuts, made with the aid of razor blades and box cutters. Calcareous algae were analyzed based on prior decalcification by immersing the samples in 0.6 M nitric acid. For specific identification, references commonly used in phycology were used (Dawes & Mathieson, 2008; Littler & Littler, 2000; Nunes, 2005b; Nunes & Guimarães, 2008; Nunes & Paula, 2000, 2001, 2002). For the arrangement of taxa, the taxonomic arrangement of Guiry and Guiry (2025) was mainly followed.

For the analysis of dry biomass, the infrageneric taxa were previously identified, separated and dried in an oven at 60 ºC for 48 hours and weighed until constant biomass was obtained. The results are presented in grams/m² of dry weight. The results for each reef zone were compared regarding the total number of taxa, and dry biomass using Shannon-Wiener diversity (H’) and Pielou equitability (J) indexes.

Using the macroalgae biomass data found in each reef zone, the Kruskal-Wallis test was performed to check whether there was a significant difference between the biomass recorded in the different zones. The Bray-Curtis similarity index was also calculated with the biomass data and Non-metric Multidimensional Scaling (nMDS) was performed using the transformed data. ANOSIM was performed for values in which there was a significant difference between the similarity results. The analyses were carried out using SigmaPlot 12 and Primer V6 software.

The species dominance index is used to assess how much one or a few species stand out in relation to the others within a biological community. It considers the proportion of individuals or the biomass of each species, allowing us to identify which of them exert the greatest influence on the structure and functioning of the ecosystem. The higher the value of the index, the greater the dominance, which indicates that a few species concentrate the majority of the individuals present. On the other hand, lower values reflect a more balanced and diverse community, with a lower concentration of individuals in a few species (Melo, 2008).

Simpson’s dominance index was used, calculated as D = ∑ (ni/N) 2, where ni is the number of individuals of a species and N is the total number of individuals of all species in the community. The value of D varies between 0 and 1, with values close to 1 indicating high dominance, that is, few species dominate the environment, while values close to 0 indicate greater diversity and balanced distribution among species.

The Feldmann index (obtained by dividing the number of species of Rhodophyta by that of Phaeophyceae [R/P]) and the Cheney index (adding the number of species of Rhodophyta to that of Chlorophyta, and dividing this value by the number of browns [R + C/ P]) (Figueiredo et al., 2008).

Results

Fifty-two taxa were identified, 27 (52) belonging to the Rhodophyta, 16 (31) Chlorophyta, and 9 (17) Phaeophyceae (Heterokontophyta). Table 1 presents the taxa, their distribution throughout the 3 zones of the reef and their respective morphotypes.

Among the zones, TP presented the greatest species richness (34) with Rhodophyta as the most representative group, 17 taxa, followed by Chlorophyta (11) and Phaeophyceae (6). Chaetomorpha minima, Gayliella dawsonii, Gracilaria ferox, Lejolisia mediterranea, Ptilothamnion speluncarum, and Stylonema alsidii were unique to this environment. PR was second in terms of species richness, such as Caulerpa chemnitzia, Caulerpa sertularioides, Cladophora corallinicola, Hypnea pseudomusciformis, Hypnea sp. 1, and Melanothamnus gorgoniae only occurred in this region. FR presented the lowest richness among the environments, such as Ceramium corniculatum, Codium taylori, Dictyopteris jamaicensis, Dictyopteris polypodioides, Sphacelaria tribuloides, and Wrangelia argus, all exclusive for the region. However, it is worth highlighting a greater representation of rhodophytes for the protected and FR.

Among the species found, 16 occurred in all regions such as Amansia multifida, Amphiroa anastomosans, Anadyomene stellata, Bryopsis pennata, Colpomenia sinuosa, Crouania attenuata, Dictyopteris delicatula, Dictyosphaeria versluysii, Dictyota mertensii, Gelidiella acerosa, Halimeda opuntia, Jania pedunculata var. adhaerens, Palisada perforata, Phyllodictyon anastomosans, Ulva flexuosa, and Ulva rigida.

Regarding the morphotypes, among the 52 taxa found, 19 were filamentous, 17 cylindrical-corticates, 9 foliaceous, 3 articulated calcareous, 3 encrusting and 1 coriaceous. Cylindrical-corticate algae were well represented in the 3 regions, predominating in the PR, followed by foliaceous algae; in the TP, the filamentous morphotype was the one with the highest representation, followed by cylindrical-corticated and foliaceous ones, the same pattern was observed in the FR.

The diversity of analysis based on the Shannon-Wiener index, showed that the TP is more diverse than the others, followed by the PR, and finally by the FR. Dominance values are inversely proportional to diversity values, which shows that in the FR, there is dominance of one or a few species over the others (Table 2).

In table 3, biomass data and the percentage of contribution of each macroalgae in the zone biomass are presented. The average total biomass of each zone was 108.01 g.m-2 in the FR, 48.83 g.m-2 in tide pool and 474.59 g.m-2 in the PR. The Kruskal-Wallis test showed that no significant differences were found in macroalgal biomass between the three reef zones analyzed (Kruskal-Wallis p = 0.869). However, the ordering of the sampling points according to the presence/absence of macroalgae (Fig. 2) shows the dispersion of samples in the 3 zones, mainly samples from the PR. The ANOSIM analysis (Table 4) shows that there was a significant difference between the FR and the TP, and between the FR and the PR, but there was no significant difference between the PR and the TP. The Feldmann and Cheney indices (Fig. 3) for the 3 reef regions studied were consistent with the flora of tropical and warm temperate regions.

Table 1

List of taxa found in the reef zones on Itapuã beach and their respective morphotypes: PR = Protected Region; TP = Tide Pool; FR = Frontal Region. Morphotypes: FT = filamentous; FC = foliaceous; CC = cylindrical corticates; CR = coriaceous; AC = articulated calcareous; E = encrusting. Presence (+) and absence (–).

| Taxa | PR | TP | FR | Morphotype |

| Chlorophyta | ||||

| Ulvophyceae | ||||

| Bryopsidales | ||||

| Bryopsidaceae | ||||

| Bryopsis pennata J.V. Lamouroux | + | + | + | FT |

| Caulerpaceae | ||||

| Caulerpa chemnitzia (Esper) J.V. Lamouroux | + | – | – | CC |

| C. racemosa (Forsskål) J. Agardh | + | + | + | CC |

| C. sertularioides (S.G. Gmelin) M. Howe | + | – | – | CC |

| Codiaceae | ||||

| Codium taylorii P.C. Silva | – | – | + | CC |

| Halimedaceae | ||||

| Halimeda opuntia (Linnaeus) J.V. Lamouroux | + | + | + | AC |

| Ulva flexuosa Wulfen | + | + | + | FC |

| U. rigida C. Agardh | + | + | + | FC |

| Cladophorales | ||||

| Anadyomenaceae | ||||

| Anadyomene stellata (Wulfen) C. Agardh | + | + | + | FC |

| Boodleaceae | ||||

| Phyllodictyon anastomosans (Harvey) Kraft & M.J. Wynne | + | + | + | FT |

| Cladophoraceae | ||||

| Chaetomorpha minima Collins & Hervey | – | + | – | FT |

| Cladophora corallinicola Sonder | + | – | – | FT |

| C. laetevirens (Dillwyn) Kützing | – | + | + | FT |

| C. vagabunda (Linnaeus) Hoek | + | – | + | FT |

| Siphonocladaceae | ||||

| Dictyosphaeria versluysii Weber Bosse | + | + | + | E |

| Valoniaceae | ||||

| Valonia aegagropila C.Agardh | + | + | – | CC |

| Heterokontophyta | ||||

| Phaeophyceae | ||||

| Dictyotales | ||||

| Dictyotaceae | ||||

| Dictyopteris delicatula J.V. Lamouroux | + | + | + | FC |

| D. jamaicensis W.R. Taylor | – | – | + | FC |

| D. polypodioides (De Candolle) J.V. Lamouroux | – | – | + | FC |

| Dictyota mertensii (C.Martius) Kützing | + | + | + | FC |

| Table 1. Continued | ||||

| Taxa | PR | TP | FR | Morphotype |

| Padina antillarum (Kützing) Piccone | + | + | – | FC |

| Spatoglossum schroederi (C. Agardh) Kützing | – | + | + | FC |

| Ectocarpales | ||||

| Scytosiphonaceae | ||||

| Colpomenia sinuosa (Mertens ex Roth) Derbès & Solier | + | + | + | E |

| Fucales | ||||

| Sargassaceae | ||||

| Sargassum polyceratium Montagne | – | + | + | CR |

| Sphacelariales | ||||

| Sphacelariaceae | ||||

| Sphacelaria tribuloides Meneghini | – | – | + | FT |

| Rhodophyta | ||||

| Florideophyceae | ||||

| Ceramiales | ||||

| Callithamniaceae | ||||

| Crouania attenuata (C. Agardh) J. Agardh | + | + | + | FT |

| Ceramiaceae | ||||

| Ceramium corniculatum Montagne | – | – | + | FT |

| Centroceras clavulatum (C. Agardh) Montagne | + | – | – | FT |

| Gayliella dawsonii (A.B. Joly) Barros-Barreto & F.P. Gomes | – | + | – | FT |

| Ceramothamnion brasiliensis (A.B. Joly) M.J. Wynne & C.W. Schneider | + | – | + | FT |

| Rhodomelaceae | ||||

| Alsidium triquetrum (S.G. Gmelin) Trevisan | – | + | – | CC |

| Amansia multifida J.V. Lamouroux | + | + | + | CC |

| Digenea simplex (Wulfen) C. Agardh | + | + | – | CC |

| Herposiphonia bipinnata M. Howe | – | + | – | FT |

| H. tenella (C. Agardh) Ambronn | – | + | – | FT |

| Melanothamnus gorgoniae (Harvey) Díaz-Tapia & Maggs | + | – | – | FT |

| Palisada perforata (Bory) K.W. Nam | + | + | + | CC |

| Wrangeliaceae | ||||

| Lejolisia mediterranea Bornet | – | + | – | FT |

| Ptilothamnion speluncarum (Collins & Hervey) D.L. Ballantine & M.J. Wynne | – | + | – | FT |

| Wrangelia argus (Montagne) Montagne | – | – | + | FT |

| Corallinales | ||||

| Corallinaceae incrustante | ||||

| Jania pedunculata var. adhaerens (J.V. Lamouroux) A.S. Harvey, Woelkerling & Reviers | + | + | + | AC |

| Corallinaceae incrustante | + | – | + | E |

| Lithophyllaceae | ||||

| Table 1. Continued | ||||

| Taxa | PR | TP | FR | Morphotype |

| Amphiroa anastomosans Weber-van Bosse | + | + | + | AC |

| Gelidiales | ||||

| Gelidiaceae | ||||

| Gelidium capense (S.G. Gmelin) P.C. Silva | + | – | + | CC |

| Gelidiellaceae | ||||

| Gelidiella acerosa (Forsskål) Feldmann & Hamel | + | + | + | CC |

| G. ligulata E.Y. Dawson | + | – | + | CC |

| Gigartinales | ||||

| Cystocloniaceae | ||||

| Hypnea pseudomusciformis Nauer, Cassano & M.C. Oliveira | + | – | – | CC |

| Hypnea sp.1 | + | – | – | CC |

| Gigartinaceae | ||||

| Chondracanthus acicularis (Roth) Fredericq | + | + | – | CC |

| Gracilariales | ||||

| Gracilariaceae | ||||

| Gracilaria ferox J. Agardh | – | + | – | CC |

| Nemaliales | ||||

| Galaxauraceae | ||||

| Galaxaura rugosa (J. Ellis & Solander) J.V. Lamouroux | – | + | + | CC |

| Stylonematophyceae | ||||

| Stylonematales | ||||

| Stylonemataceae | ||||

| Stylonema alsidii (Zanardini) K.M. Drew | – | + | – | FT |

| Total | 33 | 34 | 32 |

Discussion

Rhodophyta was the most representative group in the present study, followed by Chlorophyta and Phaeophyceae. This pattern has been observed in other studies on phytobenthic macroalgal communities as typical on the Brazilian coast (Braga et al., 2014; Costa et al., 2012; Ferreira et al., 2022). It should be noted that rhodophytes tend to dominate the environment in the absence of large brown algae in tropical environments, suggesting that there is competition between algae that use different strata in the phytobenthic community (Figueiredo et al., 2004). Furthermore, studies have confirmed the decline of Phaeophyceae at the same rate that Chlorophyta species have been increasing, which can be attributed to the negative effects of anthropogenic impact on the coastal environment (Oliveira & Qi, 2003; Scherner et al., 2013). Representatives of Phaeophyceae are more sensitive to pollutants (heavy metals and excess organic matter produced by sewage), which can even negatively affect the germination and cell division of these organisms (Kevekordes, 2001). Representatives of Chlorophyta, such as species of Ulva Linnaeus, have the capacity of benefit from contamination by pollutants, being considered opportunistic species (Scherner et al., 2012).

Table 2

Shannon-Wiener Diversity index, dominance and equitability of macroalgae in the intertidal region of Itapuã beach.

| Region | Shannon-Wiener | Dominance | Equability (J’) |

| Frontal Region | 3.466 | 0.0312 | 1 |

| Tide Pool | 3.526 | 0.0294 | 1 |

| Protected Region | 3.497 | 0.0303 | 1 |

The taxa that contributed most to the average biomass of macroalgae found on Itapuã beach were Amphiroa anastomosans, Digenea simplex, Gelidiella acerosa, and Sargassum polyceratium. It has been previously reported that algae with greater structural complexity, such as corticate algae, are better adapted to environments with greater hydrodynamics and luminosity, as this morphotype confers greater resistance to desiccation (Costa et al., 2012; Villaça et al., 2008).

Table 3

Biomass and percentage of contribution of macroalgae species in the constitution of biomass in each of the zones studied: FR = Frontal Region, TP = Tide Pool, and PR = Protected Region. Pi = Percentage of importance.

| Taxa | FR (g.m-2) | Pi | TP (g.m-2) | Pi (%) | PR (g.m-2) | Pi (%) |

| Amphyroa anastomosans | 70.07 | 64.87 | 15.76 | 32.28 | 31.59 | 6.66 |

| Anadyomene stellata | 1.41 | 1.31 | 1.76 | 3.61 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Bryopsis pennata | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 0.42 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Caulerpa racemosa | 1.42 | 1.32 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| C. sertularioides | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.11 | 0.23 |

| Centroceras clavulatum | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.25 | 0.05 |

| Chondracanthus acicularis | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Cladophora vagabunda | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.15 | 0.03 |

| Colpomenia sinuosa | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.15 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Dictyopteris delicatula | 5.42 | 5.01 | 5.48 | 11.22 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| D. jamaicensis | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Dictyosphaeria versluysii | 0.67 | 0.62 | 0.25 | 0.51 | 0.09 | 0.02 |

| Dictyota mertensii | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.13 | 0.24 |

| Digenea simplex | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.97 | 1.98 | 430.92 | 90.80 |

| Gelidiellaceae | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.00 | 4.09 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Gelidium sp. 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.94 | 1.92 | 0.19 | 0.04 |

| Gelidium sp. 2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.02 |

| Gelidiella acerosa | 14.27 | 13.21 | 5.97 | 12.24 | 2.69 | 0.57 |

| G. ligulata | 0.71 | 0.66 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Halimeda opuntia | 0.31 | 0.29 | 2.14 | 4.38 | 0.48 | 0.10 |

| Hypnea sp. 1 | 0.40 | 0.37 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Hypnea sp. 2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Jania pedunculata var. adhaerens | 7.60 | 7.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.27 | 0.06 |

| Lobophora variegata | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.39 | 0.80 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Padina antillarum | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.26 | 4.64 | 1.15 | 0.24 |

| Palisada perforata | 4.86 | 4.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.01 |

| Phyllodictyon anastomosans | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Sargassum polyceratium | 0.00 | 0.00 | 9.69 | 19.85 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Spatoglossum schroederi | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Ulva rigida | 0.63 | 0.58 | 0.83 | 1.69 | 3.55 | 0.75 |

| Valonia aegagropila | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.11 | 0.22 | 0.86 | 0.18 |

| Total | 108.01 | 48.83 | 474.59 |

The difference found in macroalgae biomass between reef zones can be explained by the hydrodynamics to which they are exposed on the reef, being wave action the main responsible for the spatial distribution of the community on the reef. The movement of waves helps to obtain nutrients, favoring the productivity of macroalgae and thus increasing biomass, however this only applies to those algae that have adaptations to resist the impact of waves, as they are also responsible for removing macroalgae from the substrate (Diez et al., 2003; Hurd et al., 1996; Leigh et al., 1987).

The highest biomasses were found in FR and PR. The FR is constantly submerged and this favors the establishment of algae, as they are submerged for longer, suffer less desiccation and are less exposed to direct sunlight. The lowest biomass values were recorded in the TP, a region that retains water during low tide, however the algae are subjected to intense solar radiation, high salinity and water temperature. The negative effects of these stressors result in lower biomass and also there is less hard substrate for fixation (Costa et al., 2012; Villaça et al., 2010).

Table 4

Results of ANOSIM tests for significance of differences between sample groups based on observed macroalgal species distribution data.

| Reef regions | (Global R= 0.613; significance level = 0.4%) | |

| Region pairs | Statistical R | Level |

| FR, TP | 0.815 | 10 |

| FR, PR | 0.667 | 10 |

| TP, PR | 0.481 | 20 |

The dominance of filamentous, cylindrical-corticate and foliaceous morphotypes was observed, corroborating the model by Orfanidis et al. (2001), which proposes that impacted environments should have a greater abundance of algae with intensely branched (corticated), laminar (foliaceous) and filamentous thallus, characterized by high growth rates and a short life cycle (annual). However, conserved environments would have an abundance of algae with thick thallus (coriaceous), articulated calcareous and encrusting, cacterized by low growth rates and a long life cycle (perennial), which reflected in the low representation of articulated, encrusting and coriaceous calcareous morphotypes. In a study carried out by Nascimento (2013) in Salvador and the North Coast of Bahia, the foliaceous and cylindrical-corticate morphotypes were more representative in both impacted and preserved environments, highlighting the predominance of these morphotypes.

The distribution of algae according to morphofunctional groups reflects the conditions of reef zones, since each taxa has its adaptive characteristics. Cylindrical-cortical algae were well represented in the 3 reef zones, with a predominance in the PR, as this morphology confers greater resistance to desiccation, helping these algae to establish themselves in different environments (Costa et al., 2012; Villaça et al., 2008). Tide pool region was dominated by filamentous algae, morphotype usually associated with benthic communities in early successional stages as they show rapid growth (Braga et al., 2014).

Regarding phytogeography, the Feldmann (F) and Cheney (C) indices found for the different regions of the Itapuã reef characterized the PR and the TP as tropical and the FR as warm temperate, according to the classification proposed by Horta et al. (2001). Factors such as the greater hydrodynamism in the FR may justify this classification in relation to its algal community, since the increase in the number of species of brown algae is noticeable as one approaches the FR. Bouzon et al. (2006), studying floristic and phytogeographic aspects of marine macroalgae in the Bays of Santa Catarina, attributed the variations in the Feldmann and Cheney indices to the exclusion of species of brown algae and the favoring of opportunistic species of red and green algae; in this study, lower values of these indices were recorded in the frontal zones and in the pool zone, where the richness of species of brown algae was greater.

Understanding the composition and structure of phytobenthic communities on the Brazilian coast, as well as on the coast of Bahia is extremely important. Despite the vast coastal extension, there are few studies referring to the algal community structure in intertidal zone as most studies focus on the subtidal zone. Also, most studies on the composition and structure of phytobenthic communities are restricted to the state of Rio de Janeiro. More studies should be carried out along the coast of Bahia to fill the gaps and alternating dry and rainy periods and/or comparing the reef zones of different beaches in the intertidal zone. The results suggest that the Itapuã reefs are in a good state of conservation.

Acknowledgements

CCSN, acknowledges the post-doctoral scholarship to the State University of Southwest Bahia (UESB) – Notice 266/2023.; CCSN, LPC, EMSP, to the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel – Brazil (CAPES), finance code 001; CCS, to the Bahia Research Support Foundation (FAPESB – T.O. B., No. BOL0416/2017) for a scholarship.; JMCN, to the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), Brazil for the research productivity fellowship (308261/2022-4).

References

Altamirano, M., & Nunes, J. M. C. (1997). Contribuciones al macrofitobentos del Município de Camaçari (Bahia, Brasil). Acta Botanica Malacitana, 22, 211–215. https://doi.org/10.24310/abm.v22i0.8639

Amado Filho, G. M., Barreto, M. B. B., Marins, B. V., Felix, C., & Reis, R. P. (2003). Estrutura das comunidades fitobentônicas do infralitoral da Baía de Sepetiba, RJ, Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Botânica, 26, 329–342. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0100-84042003000300006

Amorin, P. R. R., Moura, C. W. N., & Moniz-Brito, K. L. (2008). Estudo morfotaxonômico das espécies de Halimeda, Penicillus e Udotea (Bryopsidales, Chlorophyta) do Recife de Franja da Ilha de Itaparica, Bahia. Anais do XI Congresso Brasileiro de Ficologia & Simpósio Latino-Americano sobre Algas Nocivas. Rio de Janeiro: Museu Nacional. Série Livros.

Barbosa, S. O., Figueiredo, M. A. O., & Testa, V. (2008). Structure and dynamic of benthic communities dominated by macrophytes in praia de Jacaraípe, Espírito Santo, Brazil. Hoehnea, 35, 563–575. https://doi.org/10.1590/S2236-89062008000400008

Barreto, M. B. B., Brasileiro, P. S., Nunes, J. M. C., & Amado-Filho, G. M. (2008). Algas marinhas bentônicas do sublitoral das formações recifais da Baía de Todos os Santos, BA – 1. Novas ocorrências. Hoehnea, 31, 321–330.

Braga, A. C. S., Tâmega, F. T. S., Pedrini, A. G., & Muniz, R. A. (2014). Composição e estrutura da comunidade fitobentônica do infralitoral da praia de Itaipu, Niterói, Brasil: Subsídios para monitoramento e conservação. Iheringia. Série Botânica, 69, 267–276. https://isb.emnuvens.com.br/iheringia/article/view/90

Bouzon, J. L., Salles, J. P., Bouzon, Z., & Horta, P. A. (2006). Aspectos florísticos e fitogeográficos das macroalgas marinhas das baías da ilha de Santa Catarina, SC,Brasil. Insular, 35, 69–84.

Caires, T. A., Costa, I. O., Jesus, P. B. D., Matos, M. R. B. D., Pereira-Filho, G. H., & Nunes, J. M. D. C. (2013). Evaluation of the stocks of Hypnea musciformis (Rhodophyta: Gigartinales) on two beaches in Bahia, Brazil. Brazilian Journal of Oceanography, 61, 65–71. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1679-87592013000100007

Costa-Júnior, O. S., Attrill, M. J., Pedrini, A. G., & De Paula, J. C. (2002). Spatial and seasonal distribution of seaweeds on coral reefs from Southern Bahia, Brazil. Botanica Marina, 45, 346–355. https://doi.org/10.1515/BOT.2002.035

Costa, I. O., Caires, T. A., Pereira-Filho, G. H., & Nunes, J. M. C. (2012). Macroalgas bentônicas associadas a bancos de Hypnea musciformis (Wulfen) J.V. Lamour. (Rhodophyta-Gigartinales) em duas praias do litoral baiano. Acta Botanica Brasilica, 26, 493–507. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-33062012000200025

Dawes, C., & Mathieson, A. (2008). The seaweeds of Florida. Gainesville: University of Florida Press.

Diez, I., Santolaria, A., & Gorostiaga, J. M. (2003). The relationship of environmental factors to the structure and distribution of subtidal seaweed vegetation of the western Basque coast (N Spain). Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 56, 1041–1054. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7714(02)00301-3

Ferreira, S. M. C., Lolis, L. A., Noga, P. M., Affe, H. M. J., & Nunes, J. M. C. (2022). A highly diverse phytobenthic community along a short coastal reef gradient in northeastern Brazil. Universitas Scientiarum, 27, 34–56. https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.SC271.ahdp

Figueiredo, M. A. O., Barreto, M. B. B., & Reis, R. P. (2004). Caracterização das macroalgas nas comunidades marinhas da área de Proteção Ambiental de Cairuçú, Parati, RJ – Subsídios para futuros monitoramentos. Revista Brasileira de Botânica, 27, 11–17. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-84042004000100002

Figueiredo, M. A. O., Horta, P.A., Pedrini, A. G., & Nunes, J. M. C. (2008). Benthic marine algae of the coral reefs of Brazil: a literature review. Oecologia Brasiliensis, 12, 259–270. https://doi.org/10.4257/oeco.2008.1202.07

Guiry, M. D., & Guiry, G. M. (2025). AlgaeBase. World-wide electronic publication, University of Galway. Retrieved on February 21, 2025 from: https://www.algaebase.org

Horta, P. A., Amancio, E., Coimbra, C. S., & Oliveira, E. C. (2001). Considerações sobre a distribuição e origem da flora de macroalgas marinhas brasileiras. Hoehnea, 28, 243–265.

Horta, P. A., Salles, J. P., Bouzon, J., Scherner, F., Cabral, D., Bouzon, Z. L. et al. (2008). Composição e estrutura dos fitobentos do infralitoral da Reserva Biológica Marinha do Arvoredo, Santa Catarina, Brasil —implicações para a conservação. Oecologia Brasiliensis, 12, 51–57. https://doi.org/10.4257/oeco.2008.1202.06

Hurd, C. L., Harrison, P. J., & Druehl, L. D. (1996). Effect of seawater velocity on inorganic nitrogen uptake by morphologically distinct forms of Macrocystis integrifolia from wave-sheltered and exposed sites. Marine Biology, 126, 205–214. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00347445

Kevekordes, K. (2001). Toxicity tests using developmental stages of Hormosira banksii (Phaeophyta) identify ammonium as a damaging component of secondary treated sewage effluent discharged into Bass Strait, Victoria, Australia. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 219, 139–148. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps219139

Leigh, E. G., Paine, R. T., Quinn, J. F., & Suchanek, T. H. (1987). Wave energy and intertidal productivity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 84, 1314–1318. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.84.5.1314

Littler, D. S., & Littler, M. M. (2000). Caribbean reef plants. An identification guide to the reef plants of the Caribbean, Bahamas, Florida and Gulf of Mexico. Washington D.C.: OffShore Graphics.

Macedo, T. S., Varjão, A. S., Fernandes, L. L., Silva, D. F., Almeida, J. S., Messias, J. C. et al. (2009). Levantamento taxonômico e diversidade das macroalgas marinhas bentônicas da praia da Pituba, Salvador, Bahia. Revista Eletrônica de Biologia, 2, 29–39.

Marins, B. V., Brasileiro, P. A., Barreto, M. B. B., Nunes, J. M. C., Yoneshigue-Valentin, Y., & Amado-Filho, G. M. (2008). Subtidal benthic marine algae of the Todos os Santos Bay, Bahia State, Brazil. Oecologia Brasiliensis, 12, 229–242. https://doi.org/10.4257/oeco.2008.1202.05

Melo, A. S. (2008). O que ganhamos “confundindo” riqueza de espécies e equabilidade em um índice de diversidade? Biota Neotropica, 8, 21–27. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1676-06032008000300001

Muñoz, A. O. M., & Pereira, S. M. B. (1997). Caracterização quali-quantitativa das comunidades de macroalgas nas formações recifais da praia do Cupe Pernambuco, Brasil. Trabalhos Oceanográficos da Universidade Federal do Pernambuco, 25, 93–109. https://doi.org/10.5914/tropocean.v25i1.2731

Nascimento, O. S. (2013). Impactos da urbanização sobre a estrutura, cobertura de morfotipos funcionais e heterogeneidade química das comunidades de algas

recifais (M.Sc. Thesis). Instituto de Biologia, Universidade Federal da Bahia, Salvador.

Nunes, J. M. C. (1998a). Catálogo de algas marinhas bentônicas do Estado da Bahia. Acta Botanica Malacitana, 23, 5–21. https://doi.org/10.24310/abm.v23i0.8547

Nunes, J. M. C. (1998b). Rodofíceas marinhas bentônicas da orla oceânica de Salvador, Estado da Bahia, Brasil. Insula, 49, 27–37.

Nunes, J. M. C. (1999). Phaeophyta da Região Metropolitana de Salvador, Bahia, Brasil (M.Sc. Thesis). Instituto de Biociências, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo.

Nunes, J. M. C. (2005a). A família Liagoraceae (Rhodophyta, Nemaliales) no Estado da Bahia, Brasil. Hoehnea, 32, 429–444.

Nunes, J. M. C. (2005b). Rodofíceas marinhas bentônicas do Estado da Bahia, Brasil (Ph.D. Thesis). Instituto de Biociências, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo.

Nunes, J. M. C. (2010). Taxonomia morfológica: metodologia de trabalho. In A. G. Pedrini (Org.), Macroalgas: uma introdução à Taxonomia (pp. 53–70). Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro: Technical Books.

Nunes, J. M. C., & Guimarães, S. M. P. B. (2008). Novas referências de rodofíceas marinhas bentônicas para o litoral brasileiro. Biota Neotrópica, 8, 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1676-06032008000400008

Nunes, J. M. C., & Guimarães, S. M. P. B. (2009). Primeira referência de plantas gametofíticas em Spermothamnion nonatoi (Ceramiales, Rhodophyta). Rodriguésia, 60, 259–264. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23499987

Nunes, J. M. C., & Guimarães, S. M. P. B. (2010). Morfologia y toxonomía de Scinaia halliae (Scinaiaceae, Rhodophyta) em el litoral de Bahia y Espírito Santo, Brasil. Revista

de Biología Marina y Oceonografía, 45, 159–164. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-19572010000100017

Nunes, J. M. C., & Paula, E. J. (2000). Estudos taxonômicos do gênero Padina Adanson (Dictyotaceae – Phaeophyta) no litoral do Estado da Bahia, Brasil. Acta Botanica Malaci-

tana, 26, 21–43. https://doi.org/10.24310/abm.v25i0.8470

Nunes, J. M. C., & Paula, E. J. (2001). O gênero Dictyota Laumouroux (Dictyotaceae – Phaeophyta) no litoral do Estado da Bahia, Brasil. Acta Botanica Malacitana, 26, 5–18. https://doi.org/10.24310/abm.v26i0.7375

Nunes, J. M. C., & Paula, E. J. (2002). Composição e distribuição das Phaeophyta nos Recifes da Região Metropolitana de Salvador, Bahia, Brasil. Iheringia, 57, 113–130.

Nunes, J. M. C., & Paula, E. J. (2004a). Chnoosporaceae, Scytosiphonaceae, Sporochnaceae e Sphacelariaceae (Phaeophyta) no Estado da Bahia, Brasil. Biotemas, 17, 7–28.

Nunes, J. M. C., & Paula, E. J. (2004b). Estudos taxonômicos de Ectocarpaceae e Ralfsiaceae (Phaeophyta) da Região Metropolitana de Salvador, Ba, Brasil. Acta Biologica Leopoldensia, 26, 37–50.

Nunes, J. M. C., & Paula, E. J. (2006). O gênero Dictyopteris J.V.Lamour. (Dictyotaceae – Phaeophyta) no estado da Bahia, Brasil. Hidrobiológica, 16, 251–258. https://hidro

biologica.izt.uam.mx/index.php/revHidro/article/view/1036

Nunes, J. M. C., Santos, A. C. C., & Santana, L. C. (2005). Novas ocorrências de algas marinhas bentônicas para o Estado da Bahia, Brasil. Iheringia Série Botânica,60,

99–106. https://isb.emnuvens.com.br/iheringia/article/view/209

Oliveira, E. C., & Qi, Y. (2003). Decadal changes in a polluted bay as seen from its seaweed flora: the case of Santos Bay in Brazil. AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment, 32, 403–405. https://doi.org/10.1579/0044-7447-32.6.403

Orfanidis, S., Panayotidis, P., & Stamatis, N. (2001). Ecological evaluation of transitional and coastal waters: a marine benthic macrophytes-based model. Mediterranean Marine Science, 2, 45–65. https://doi.org/10.12681/mms.266

Pedrini, A. G. (2013). Macroalgas (ocrófitas multicelulares) marinhas do Brasil. Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro: Technical Books.

Scherner, F., Barufi, J. B., & Horta, P. A. (2012). Photosynthetic response of two seaweed species along an urban pollution gradient: evidence of selection of pollution-tolerant species. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 64, 2380–2390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2012.08.012

Scherner, F., Horta, P. A., De Oliveira, E. C., Simonassi, J. C., Hall-Spencer, J. M., Chow, F. et al. (2013). Coastal urbanization leads to remarkable seaweed species loss and community shifts along the SW Atlantic. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 76, 106–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2013.09.019

Steneck, R. S., & Dethier, M. N. (1994). A functional group approach to the structure of algal-dominated communities. Oikos, 69, 476-498. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3545860

Villaça, R., Yoneshigue-Valentin, Y., & Boudouresque, C. F. (2008). Estrutura da comunidade de macroalgas do infralitoral do lado exposto da ilha de Cabo Frio (Arraial do Cabo, RJ). Oecologia Brasiliensis, 12, 206–221. https://doi.org/10.4257/oeco.2008.1202.03

Villaça, R., Carvalhal-Fonseca, A., Jensen, V. K., & Knoppers, B. (2010). Species composition and distribution of macroalgae on Atol das Rocas, Brazil, SW Atlantic. Botanica Marina, 53, 113–122. https://doi.org/10.1515/BOT.2010.013

Zar, J. H. (2010). Biostatistical analysis. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall International.