Edmundo González-Santillán a, Laura L. Valdez-Velázquez b, *, Ofelia Delgado-Hernández c, Jimena I. Cid-Uribe d, María Teresa Romero-Gutiérrez e, Lourival D. Possani d

a Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Biología, Departamento de Zoología, Colección Nacional de Arácnidos, Tercer Circuito Exterior s/n, Ciudad Universitaria, Coyoacán, 04510 Ciudad de México, Mexico

b Universidad de Colima, Facultad de Ciencias Químicas y Facultad de Medicina, Km 9 Carretera Colima-Coquimatlán, 28400 Coquimatlán, Colima, Mexico

c Instituto Francisco Possenti, Av. Toluca 621, Olivar de los Padres, Álvaro Obregón, 01780 Mexico City, Mexico

d Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Biotecnología, Avenida Universidad 2001, Colonia Chamilpa, 62210 Cuernavaca, Morelos, Mexico

e Universidad de Guadalajara, Centro Universitario Tlajomulco, Departamento de Innovación Tecnológica, Carretera Tlajomulco – Santa Fé Km. 3.5 No.595 Lomas de Tejeda, 45641 Tlajomulco de Zúñiga, Jalisco, Mexico

*Corresponding author: lauravaldez@ucol.mx (L.L. Valdez-Velázquez)

Received: 9 October 2023; accepted: 19 March 2024

Abstract

Scorpion species diversity in Colima was investigated with a multigene approach. Fieldwork produced 34 lots of scorpions that were analyzed with 12S rDNA, 16S rDNA, COI, and 28S rDNA genetic markers. Our results confirmed prior phylogenetic results recovering the monophyly of the families Buthidae and Vaejovidae, some species groups, and genera. We recorded 11 described species of scorpions and found 3 putatively undescribed species of Centruroides, 1 of Mesomexovis, and 1 of Vaejovis. Furthermore, we obtained evidence that Centruroides elegans, C. infamatus,and C. limpidus do not occur in Colima, contrary to prior reports. Seven genetically different and medically relevant species of Centruroides for Colima are recorded for the first time. We used the InDRE database (Instituto de Diagnóstico y Referencia Epidemiológicos), which contains georeferenced points of scorpions, to estimate the distribution of the scorpion species found in our fieldwork. Finally, we discuss from a biogeographical, ecological, and medical point of view the presence and origin of the 14 scorpion species found in Colima.

Keywords: Barcoding; Holotype; Medical relevance; Microendemic; New species; Species group; Substrate-specialist

© 2024 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Biología. Este es un artículo Open Access bajo la licencia CC BY-NC-ND

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Una aproximación multigenes para identificar a las especies de alacranes (Arachnida: Scorpiones) de Colima, México, con cometarios sobre la diversidad de sus venenos

Resumen

La diversidad de especies de alacranes de Colima se investigó utilizando una aproximación multigenes. Del trabajo de campo se obtuvieron 34 lotes de alacranes que fueron analizados con los marcadores 12S rDNA, 16S rDNA, COI, y 28S rDNA. La comparación con trabajos de filogenia previos nos permitió confirmar la monofilia de las familias Buthidae y Vaejovidae, de algunos grupos de especies y géneros. Encontramos 11 especies de alacranes descritas, 3 putativamente nuevas de Centruroides, 1 de Mesomexovis y 1 de Vaejovis. También obtuvimos evidencia de que Centruroides elegans, C. infamatus y C. limpidus no están distribuidos en Colima, como se registró en trabajos anteriores. Reportamos 7 especies genéticamente distintas y de importancia médica para Colima. Usamos la base de datos del InDRE (Instituto de Diagnóstico y Referencia Epidemiológicos) que contiene puntos georreferenciados de alacranes para estimar la distribución de las especies que recolectamos en el campo. Finalmente, discutimos desde una perspectiva biogeográfica, ecológica y de importancia médica las 14 especies de alacranes que reportamos para Colima.

Palabras clave: Código de barras; Holotipo; Importancia médica; Microendémico; Especie nueva; Grupo de especies; Sustrato-especialista

Introduction

The knowledge of scorpion diversity in North America has improved recently (González-Santillán & Prendini, 2013; Goodman, Prendini, Francke et al., 2021; Ponce-Saavedra & Francke, 2019; Santibáñez-López et al., 2014); however, much remains to be discovered. Local-scale inventories may be a solution to unveil species communities that, in turn, can help conform regional faunas. This approach has rarely been applied to study scorpion diversity. Furthermore, few local faunal studies have been conducted in Mexico, and only a handful of them have been published; other revisionary contributions included limited fieldwork effort (Baldazo-Monsivais et al., 2012, 2016, 2017).

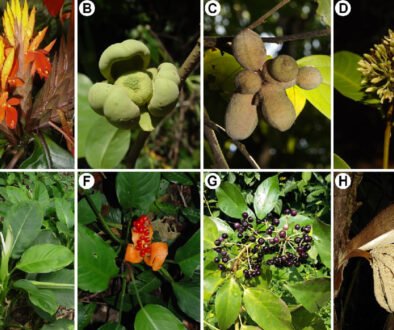

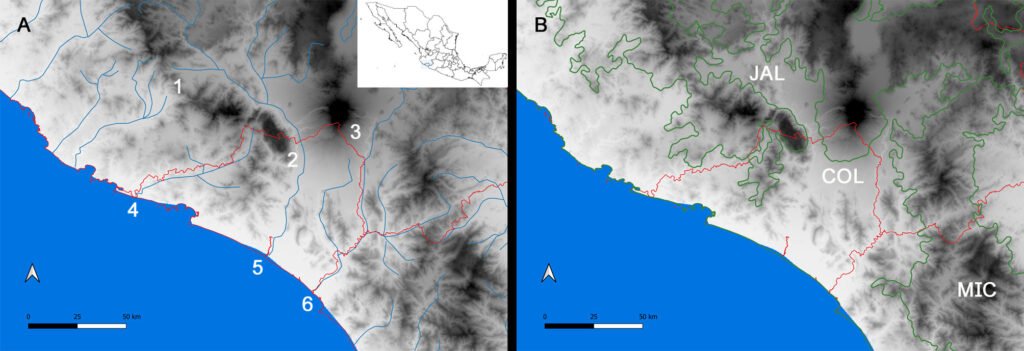

The International Barcode of Life (iBOL) has grown as a powerful tool for discovering biodiversity, among other applications (https://ibol.org). Scorpion barcoding studies have permitted the identification and delimitation of species in several regions of the world (Fet et al., 2014, 2016; Goodman, Prendini, & Esposito, 2021; Podnar et al., 2021). Despite the high diversity of scorpions in Mexico —an update by Ponce-Saavedra et al. (2023) comprises 311 scorpion species— only 1 mini-barcoding study has been conducted (Goodman, Prendini, & Esposito, 2021). Herein, we present a second scorpion barcoding study for this country but aim at discovering the components of a local scorpion assembly. Colima exhibits a complex topology comprising littorals with a tropical climate and extreme topological variation from sea level to mountain ranges rising to over 4,000 m in approximately 5,600 km2. Colima’s territory supports a rich local flora and fauna (Ramírez-Ruiz & Bretón-González, 2016). Colima lies between the limits of the Nearctic and Neotropical biogeographical Realms (Fig. 1B). Beyond its complexity, Colima represents an enclosed littoral surrounded by mountain ranges and 3 large rivers that divide the territory into 2 sections (Fig. 1), which makes it a well-defined and manageable geographical unit ideal for studying a unique community of scorpions. Thus far, 2 families, 3 subfamilies, 5 genera, and 12 species of scorpions have been identified in Colima (Table 1). The knowledge of scorpion diversity and evolutionary studies in Mexico has steadily been unveiling one of the vastest biodiversity hotspots in the world. For instance, 2 of the most diverse scorpion families and subfamilies, Vaejovidae (Syntropinae) and Buthidae (Centruroidinae), have been treated in recent phylogenetic and taxonomic analyses (Esposito & Prendini, 2019; González-Santillán & Prendini, 2013, 2015).

This contribution aims to survey the scorpion richness in Colima, using not only the COI-barcoding genetic marker but 2 additional mitochondrial markers and 1 nuclear marker to establish a framework to build a stable and predictable taxonomy. Taking advantage of robust phylogenies produced for the 2 families distributed in Colima, we use these topologies as a baseline for comparison to test the presence of several previously reported species and to taxonomically circumscribe our fresh samples. Unlike other barcoding studies, our approach seeks to unveil the richness within the state instead of focusing on delimiting the species of a taxonomic group of scorpions.

Materials and methods

We conducted field collections during May and September 2015-2018 in various ecosystems, including tropical deciduous forest, oak-pine, and tropical forest within the state of Colima, at elevations ranging from 47 to 2,200 m. (Table 2). Logistically, we leveraged our collection sites with the help of private landowners who gave us access to their property. Specimen collection methods included direct collection during the day by moving objects on the ground or by ultraviolet detection during the night. To preserve specimens, ethyl alcohol at 90% was used and stored at -80 °C. Each specimen lot carried a label with coordinates and locality information. We obtained scorpions from 14 localities and sequenced 18 samples of Centruroides from Colima (Table 2).

Table 1

List of families, subfamilies, genera, and species recorded in the state of Colima. *Species of Centruroides cited by Ponce-Saavedra et al. (2016). The species in bold font were not found in Colima in this study. Numbered species were reported by González-Santillán et al. (2019).

| Families | Subfamilies | Species |

| Buthidae | Centruroidinae | 1. Centruroides elegans (Thorell, 1876)* 2. Centruroides hirsutipalpus Ponce-Saavedra & Francke, 2009* 3. Centruroides infamatus (C.L. Koch, 1844)* Centruroides limpidus (Karsch, 1879)* Centruroides ornatus Pocock, 1902 4. Centruroides tecomanus1 Hoffmann, 1932* 5. Centruroides possanii González-Santillán, Galán-Sánchez & Valdez-Velázquez Centruroides new sp 1 Centruroides new sp 2 Centruroides tecomanus 2 |

| Vaejovidae | Syntropinae | 6. Konetontli ilitchi González-Santillán & Prendini, 2015 7. Thorellius cristimanus (Pocock, 1898) 8. Thorellius intrepidus (Thorell, 1876) 9. Mesomexovis aff. occidentalis |

| 10. Vaejovis janssi Williams, 1980 | ||

| Vaejovinae | 11. Vaejovis monticola Sissom, 1989 12. Vaejovis sp. mexicanus group |

Figure 1. Map of the west coast of Mexico. A, Orographic and hydrographic elements of Colima (COL) and the surrounding states of Jalisco (JAL) and Michoacán (MIC). 1, Manantlán Sierra; 2, massive Cerro Grande; 3, Colima Volcano; 4, Marabasco or Cihuatlán River; 5, Armería River; 6, Coahuayana River. B, Biogeographical provinces (Morrone et al., 2017). Area within the green line corresponds to the Sierra Madre del Sur and north Colima Volcano Trans Mexican Volcanic Belt province (Morrone et al., 2017) —notice that both provinces are connected in Colima. Area outside the green line corresponds to the Pacific Lowlands province (Morrone et al., 2017). Orographic components are indicated in gray scale from light low elevation to dark high elevation.

Table 2

Collection sites of the scorpion species used in this study. The number within parenthesis after the species name is the number of samples processed from this locality and included in the phylogenetic analyses as terminals. Superscript numbers indicate sources of sequences as follows: 1Bolaños et al. (2019), 2Esposito et al. (2018), 3Esposito and Prendini (2019), 4González-Santillán and Prendini (2015). Cells filled in grey color are samples obtained from GenBank.

| Species | Municipality | Locality | Latitude | Longitude | Elevation |

| Thorellius cristimanus (2) | Comala | La Yerbabuena | 19°27′59.55″ | -103°41′46.64′′ | 1,358 m |

| Centruroides ornatus (2) | Comala | Agosto | 19°23′51.74′′ | -103°44′03.08′′ | 1,076 m |

| Thorellius cristimanus | |||||

| *Centruroides tecomanus2 | Colima | Comunidad La Capacha | 19°04′58.40′′ | -103°41′24.67′′ | 656 m |

| *Centruroides tecomanus2 | Colima | Tepames | 19°06′22.8′′ | -103°59′11.07′′ | 450 m |

| Thorellius intrepidus (3) | Coquimatlán | El Palapo | 19°11′54.6′′ | -103°54′50′′ | 275 m |

| *Centruroides tecomanus2 | Cuauhtémoc | Camino a Altozano | 19°18′30.19′′ | -103°40′23.83′′ | 789 m |

| Thorellius cristimanus | |||||

| *Centruroides tecomanus1(2) | Cuauhtémoc | Ocotillo | 19°20′00.00′′ | -103°39′02.00′′ | 895 m |

| *Centruroides tecomanus2 | Ixtlahuacán | San Gabriel | 18°54′24.48′′ | -103°44′05.61′′ | 462 m |

| Mesomexovis aff. occidentalis | |||||

| Centruroides hirsutipalpus | Minatitlán | Minatitlán | 19°23′01.73′′ | -104°03′35.19′′ | 703 m |

| Centruroides possanii (2) | Minatitlán | Terrero | 19°26′35.94′′ | -103°57′05.67′′ | 2,200 m |

| Centruroides possanii (2) | Minatitlán | Mirador el Filete | 19°26′40′′ | -103°58′10′′ | 2,137 m |

| Vaejovis sp. (mexicanus group) | |||||

| Centruroides sp. 2 (2) | Manzanillo | La central | 19°08′38.14′′ | -104°26′04.10′′ | 47 m |

| *Centruroides tecomanus1 | |||||

| *Centruroides tecomanus2 | |||||

| Centruroides sp. 1 | Tecomán | Chanchopa | 18°51′58.55′′ | -103°44′10.10′′ | 41 m |

| Thorellius intrepidus (2) | Villa de Álvarez | Rancho Blanco | 19°14′24.71′′ | -103°45′49.45′′ | 455 m |

| Thorellius intrepidus4 | La Huerta (Jal.) | Estación de Biología Chamela | 19°30′14.15′′ | -105°2′16.50′′ | 33 m |

| Centruroides elegans (2) | |||||

| Centruroides suffusus | Durango (Dgo.) | El Salto, 50 km E Durango | 23°45′51.41′′ | -105°19′49.16′′ | 2,847 m |

| Centruroides limpidus | Iguala (Gro.) | Iguala | 18°20′11.87′′ | -99°29′29.65′′ | 823 m |

| Centruroides sculpturatus | Cumpas (Son.) | 18 km NE de Nacozari | 30°16.473′ | -109°50.070′ | 930 m |

| Centruroides noxius | Pantanal (Nay.) | Pantanal | 21°25′24.42′′ | -104°50′47.89′′ | 921 m |

| Centruroides huichol | Nayarit | – | – | – | – |

| Centruroides infamatus115scrp | Guanajuato (Gto.) | Guanajuato | – | – | – |

| Centruroides ornatus2LP1822 | Tandamangapio (Mich.) | Los Tabanos | 19.9749° | – 102.84226° | 223 m |

| Centruroides ornatus3 2003 | Michoacán | – | – | – | – |

| *Centruroides tecomanus11 25scrp | Comala (Col.) | – | – | – | – |

| *Centruroides tecomanus12 2007 | Michoacán | – | – | – | – |

| Mesomexovis occidentalis4 LP 7056 | Acapulco (Gro.) | Cumbres de Llano Largo | 16°49.505 | -99°49.9990 | 317 m |

| Table 2. Continued | |||||

| Species | Municipality | Locality | Latitude | Longitude | Elevation |

| Mesomexovis spadix4LP6373 | León (Gto.) | San Antonio de Padua | 20°34.5170 | -100°57.217 | – |

| Mesomexovis subcristatus4LP 2049 | Tehuacán (Pue.) | Tehuacán, 2 km east | 18°24.0020 | -97°22.8670 | 1435 m |

| Thorellius cristimanus4LP 5325 | Álvaro Obregón (Mich.) | Álvaro Obregón | 19°02.3100 | -102°58.405 | 462 m |

| Thorellius cristimanus4LP 6551 | Coquimatlán (Col.) | Road to Coquimatlán, km 71 | 19°06.7750 | -103°51.1850 | 336 m |

| Thorellius intrepidus4LP 6377 | Comala (Col.) | Comala | 19°19.000 | -103°45.0000 | – |

| Thorellius intrepidus4LP 6379 | Colima (Col.) | Los Ortices | 19°06.0468 | -103°44.0226 | 343 m |

| Vaejovis carolinianus4LP 1576 | South Carolina | – | – | – | – |

| Vaejovis pequeno4LP 6308 | Soyopa (Son.) | Sierra El Encinal, 9 km from crossroad on Highway Mex 16 to El Encinal | 28°35.4120 | -109°27.1480 | 380 m |

| Vaejovis rossmani4LP 2027 | Hidalgo (Tams.) | Conrado Castillo | 23°56.01735 | -99°28.04817 | – |

*Genetically differentiated species.

We also included 8 species from outside the state to test the presence of C. elegans, C. infamatus, and C. limpidus reported previously in the literature (Ponce-Saavedra et al., 2016); C. noxius and C. suffusus for comparative purposes and samples of C. tecomanus and C. ornatus from GenBank with a total of 31 specimens of the genus Centruroides within 4 species groups. Unlike buthids, we obtained 12 samples of vaejovids to include in this analysis. To evaluate the identity of vaejovids, we used the BLAST® suite (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) to search for similar sequences deposited in the nucleotide collection database at NCBI. Thorellius has been revised recently (González-Santillán & Prendini, 2018). Therefore, several DNA sequences are available, and fewer sequences of Mesomexovis sp. and Vaejovis sp. were available in GenBank, as they are still unrevised. Using the genetic markers as queries, we obtained 10 additional samples. The total number of taxonomic specimens used for these analyses was 53 (Tables 2, 4).

Genomic DNA was extracted from the legs or pedipalp of specimens using Qiagen Dneasy/trisol method Tissue Kits or a DNAzol Genomic DNA isolation Reagent kit (Molecular Research Center INC, Cincinnati, Oh). We amplified 3 mitochondrial markers, 12S rDNA, 16S rDNA, and the barcode COI, and the nuclear marker 28S rDNA. We performed the Polymerase Chain Reaction with the following thermal profile: an initial denaturation step (3 min at 94°C) followed by 35 cycles including denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing (46-55°C) for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 30 s, with a final extension step at 72°C for 7 min. The PCR reaction was conducted using PureTaq-Ready-To-Go PCR Beads (GE Healthcare), 2 µl of DNA template, 21 µl of DNA grade H2O, and 1 µl of each direction primer listed in Table 3. We verified PCR products with a 1% agarose-TBE electrophoresis gel stained with CYBR Safe. For purification of the amplified products, we used Ampure Magnetic Beads (Beckman-Coulter) and re-suspended in 40 µl DNA grade water by using a Beckman Coulter Biomek NX 18 robot. Each 8 µl cycle-sequenced reaction mixture included 1 µl of Big Dye, 1 µl of Big Dye Terminating buffer, 1 µl of 3.2 pm primer, and 5 µl of gene amplification product. Cycle-sequenced products were purified with CleanSeq magnetic beads on a Biomex NX robot. Products were re-suspended in EDTA, and 33 µl were processed in an Applied Biosystems, Inc. Prism 3730xl automated DNA sequencer. These products were sequenced with the same primer pairs used for amplification at the Laboratorio de Secuenciación Genómica de la Biodiversidad, at Instituto de Biología and Unidad de Síntesis y Secuenciación de DNA, Instituto de Biotecnología, UNAM. The sequences were edited using Sequencher® version 5.4.6.

Table 3

List of primers used to amplify molecular markers.

| Name | Sequence | Reference |

| 12S rDNA | ||

| 12SAI | AAACTAGGATTAGATACCCTATTAT | Kocher et al. (1989) |

| 12SBI | AAGAGCGACGGGCGATGTGT | Kocher et al. (1989) |

| 16S rDNA | ||

| 16SA | CGCCTGTTTATCAAAAACAT | Simon et al. (1994) |

| 16SB | CTCCGGTTTGAACTCAGATCA | Simon et al. (1994) |

| COI | ||

| HCO | TAAACTTCAGGGTGACCAAAAAATCA | Folmer et al. (1994) |

| LCO1 | GGTCAACAAATCATAAAGATATTGG | Folmer et al. (1994) |

| 28S rDNA | ||

| 28SA | GACCCGTCTTGAAGCACG | Nunn et al. (1996) |

| 28SBout | CCCACAGCGCCAGTTCTGCTTACC | Prendini et al. (2005) |

Each genetic fragment was aligned separately for all terminals with MAFFT using the online server (https://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/server/). Since the number of nucleotides per gene was similar, we used the G-ins-i iterative refinement method, as recommended elsewhere (Katoh et al., 2019; Kuraku et al., 2013), and other parameters were kept default. To select the best fit of the substitution model per partition and conduct the phylogenetic analyses, we used IQ-TREE version 2 (Kalyaanamoorthy et al., 2017; Nguyen et al., 2015) and we estimated branch support with 1,000 replicates of the ultrafast bootstrap (UFBOOT) algorithm (Hoang et al., 2018). Furthermore, each genetic marker was analyzed individually to explore its phylogenetic signal and contribution to the final topology. We conducted concatenated and partitioned analyses, handling all matrices in Mesquite (Maddison & Maddison, 2023). For the COI partition we explored the best codon partition per site, but the results had no effect on the topology. Additionally, to evaluate each marker and nucleotide site within each marker, we calculated the gene (GCF) and site (SCF) concordance factors on the topology that we emphasized in the discussion (Mihn et al., 2020).

Distributional records and maps. We obtained records with geographical coordinates of the scorpion species treated here via the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) from the InDRE, responsible in Mexico for epidemiological vigilance (Huerta-Jiménez, 2018), and the records published by Ponce-Saavedra et al. (2015). These records were the basis for the species distribution maps depicted in figures 3 to 6. We used the program QGIS 3.16.6-Hannove (QGIS, 2021) to create the distributional maps. The topological model with the data was from Jarvis et al. (2008), and to draw the political boundaries we used shapefiles obtained from Conabio. The biogeographic regionalization of Mexico into provinces and districts follows Morrone et al. (2017) and Morrone (2019).

Results

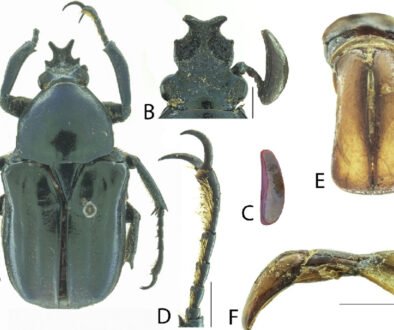

The gene fragments that we obtained are listed in Table 4 and the main statistics of the alignment and concatenated matrix are in Table 5. Our topology produced a clade representing members of the family Buthidae and another clade representing Vaejovidae (Fig. 2). Within buthids, the first clade included C. huichol and C. noxius, component species of the bertholdii species group (Ponce-Saavedra & Francke, 2019), supported by 95% UFBOOT, 100% GCF, and 40% SCF. The next clade included C. elegans, C. limpidus, and a putative undescribed species with lower support values of 68%, 100%, and 38%, respectively, including members of the elegans group. Although with low support, the bulk of species appeared in the third clade comprising species within the infamatus group, with C. tecomanus, C. infamatus, C. possanii, C. hirsuticauda, C. ornatus, and 2 putative new species. The last clade included C. suffusus and C. sculpturatus, whichPonce-Saavedra and Francke (2019) circumscribed within the infamatus and the elegans species group, respectively (Fig. 2). However, the overall topology retrieved herein is concordant with the North American clade of the genus Centruroides (Esposito & Prendini, 2019).

Table 4

Mitochondrial genetic markers 16S, COI, and 12S and nuclear 28S information for samples analyzed in the study. Dash (-) symbols indicate unavailable sequences.

| Species | NCBI:txid | 16S | 12S | COI | 28S |

| Centruroides elegans | 217897 | Cele_30_16S (PP295377) | Cele_30_12S (PP295301) | Cele_30_COI (PP356615) | Cele_30_28S (PP295328) |

| Cele_31_16S (PP295378) | Cele_31_12S (PP295302) | Cele_31_COI (PP355194) | Cele_31_28S (PP295329) | ||

| Table 4. Continued | |||||

| Species | NCBI:txid | 16S | 12S | COI | 28S |

| Centruroides hirsutipalpus | – | Chir_06_16S (PP295353) | Chir_06_12S (PP295277) | Chir_06_COI (PP356614) | Chir_06_28S (PP295310) |

| Centruroides huichol | 2911785 | Chui_38_16S (PP295385) | Chui_38_12S (PP295309) | Chui_38_COI (PP356613) | Chui_38_28S (PP295335) |

| Centruroides infamatus | 42200 | MF134694 | – | MF134798 | MF134763 |

| Centruroides limpidus | 29941 | Clim_34_16S (PP295381) | Clim_34_12S (PP295305) | Clim_34_COI (PP356612) | Clim_34_28S (PP295332) |

| Centruroides noxius | 6878 | Cnox_36_16S (PP295383) | Cnox_36_12S (PP295307) | Cnox_36_COI (PP356611) | Cnox_36_28S (PP295333) |

| Cnox_37_16S (PP295384) | Cnox_37_12S (PP295308) | Cnox_37_COI (PP356610) | Cnox_37_28S (PP295334) | ||

| Centruroides ornatus | 2338500 | Corn_03_16S (PP295350) | Corn_03_12S (PP295274) | Corn_03_COI (PP355195) | Corn_03_28S (PP295324) |

| Corn_04_16S (PP295351) | Corn_04_12S (PP295275) | Corn_04_COI (PP356609) | Corn_04_28S (PP295325) | ||

| KY981895 | KY981799 | – | KY982086 | ||

| MK479042 | MK478991 | MK479195 | MK479144 | ||

| Centruroides possanii | – | Cpos_10_16S (PP295357) | Cpos_10_12S (PP295281) | – | Cpos_10_28S (PP295314) |

| Cpos_07_16S (PP295354) | Cpos_07_12S (PP295278) | Cpos_07_COI (PP355196) | Cpos_07_28S (PP295312) | ||

| Cpos_08_16S (PP295355) | Cpos_08_12S (PP295279) | Cpos_08_COI (PP356608) | Cpos_08_28S PP295313 | ||

| Cpos_09_16S (PP295356) | Cpos_09_12S (PP295280) | Cpos_09_COI (PP356607) | Cpos_09_28S (PP295323) | ||

| Centruroides sculpturatus | 218467 | Cscu_35_16S (PP295382) | Cscu_35_12S (PP295306) | Cscu_35_COI (PP356606) | Cscu_35_28S (PP295331) |

| Centruroides sp. 1 | 3103037 | Csp1_23_16S (PP295370) | Csp1_23_12S (PP295294) | Csp1_23_COI (PP356604) | Csp1_23_28S (PP295311) |

| Centruroides sp. 2 | Csp2_11_16S (PP295358) | Csp2_11_12S (PP295282) | Csp2_11_COI (PP356603) | Csp2_11_28S (PP295327) | |

| Csp_14_16S (PP295361) | Csp_14_12S (PP295285) | Csp_14_COI (PP356605) | Csp_14_28S (PP295326) | ||

| Centruroides suffusus | 6881 | Csu_33_16S (PP295380) | Csu_33_12S (PP295304) | – | Csu_33_28S (PP295330) |

| Centruroides tecomanus1 | 1028682 | Cte1_12_16S (PP295359) | Cte1_12_12S (PP295283) | Cte1_12_COI (PP356602) | Cte1_12_28S (PP295315) |

| Cte1_17_16S (PP295364) | Cte1_17_12S (PP295288) | Cte1_17_COI (PP355197) | Cte1_17_28S (PP295320) | ||

| Cte1_18_16S (PP295365) | Cte1_18_12S (PP295289) | Cte1_18_COI (PP356601) | Cte1_18_28S (PP295318) | ||

| Centruroides tecomanus2 | Cte2_13_16S (PP295360) | Cte2_13_12S (PP295284) | Cte2_13_COI (PP356600) | Cte2_13_28S (PP295316) | |

| Cte2_15_16S (PP295362) | Cte2_15_12S (PP295286) | Cte2_15_COI (PP355198) | Cte2_15_28S (PP295317) | ||

| Table 4. Continued | |||||

| Species | NCBI:txid | 16S | 12S | COI | 28S |

| Cte2_19_16S (PP295366) | Cte2_19_12S (PP295290) | Cte2_19_COI (PP356599) | Cte2_19_28S (PP295319) | ||

| Cte2_20_16S (PP295367) | Cte2_20_12S (PP295291) | Cte2_20_COI (PP356598) | Cte2_20_28S (PP295321) | ||

| Cte2_21_16S (PP295368) | Cte2_21_12S (PP295292) | Cte2_21_COI (PP356597) | Cte2_21_28S (PP295322) | ||

| Centruroides tecomanus | MF134695 | – | MF134799 | MF134757 | |

| MK479053 | MK479002 | MK479206 | MK479156 | ||

| Mesomexovis sp. | – | Mesp_22_16S (PP295369) | Mesp_22_12S (PP295293) | Mesp_22_COI | Mesp_22_28S (PP295337) |

| Mesomexovis occidentalis | 1532992 | KM274362 | KM274216 | KM274800 | – |

| Mesomexovis spadix | 1532994 | KM274221 | KM274367 | KM274805 | KM274659 |

| Mesomexovis subcristatus | 1532995 | KM274368 | KM274222 | KM274806 | KM274660 |

| Thorellius cristimanus | 1533000 | Tcri_01_16S (PP295348) | Tcri_01_12S (PP295272) | – | Tcri_01_28S (PP295338) |

| Tcri_16_16S (PP295363) | Tcri_16_12S (PP295287) | – | Tcri_16_28S (PP295336) | ||

| Tcri_02_16S (PP295349) | Tcri_02_12S (PP295273) | – | Tcri_02_28S (PP295339) | ||

| Tcri_05_16S (PP295352) | Tcri_05_12S (PP295276) | – | Tcri_05_28S (PP295340) | ||

| KM274420 | KM274274 | KM274858 | KM274712 | ||

| KM274422 | KM274276 | KM274860 | KM274714 | ||

| Thorellius intrepidus | 1533001 | Tint_24__16S (PP295371) | Tint_24_12S (PP295295) | Tint_24_COI (PP355193) | Tint_24_28S (PP295341) |

| Tint_25_16S (PP295372) | Tint_25_12S (PP295296) | Tint_25_COI (PP356616) | Tint_25_28S (PP295342) | ||

| Tint_26_16S (PP295373) | Tint_26_12S (PP295297) | Tint_26_COI (PP356617) | Tint_26_28S (PP295343) | ||

| Tint_27_16S (PP295374) | Tint_27_12S (PP295298) | Tint_27_COI (PP355192) | Tint_27_28S (PP295344) | ||

| Tint_28_16S (PP295375) | Tint_28_12S (PP295299) | Tint_28_COI (PP356618) | Tint_28_28S (PP295345) | ||

| Tint_29_16S (PP295376) | Tint_29_12S (PP295300) | Tint_29_COI (PP356619) | Tint_29_28S (PP295346) | ||

| KM274424 | KM274278 | KM274862 | – | ||

| KM274425 | KM274279 | KM274863 | KM274717 | ||

| Vaejovis sp. | – | Vasp_32_16S (PP295379) | Vasp_32_12S (PP295303) | Vasp_32_COI (PP356620) | Vasp_32_28S (PP295347) |

| Vaejovis carolinianus | 33322 | KM274289 | KM274143 | KM274727 | KM274581 |

| Vaejovis pequeno | 1532951 | KM274293 | KM274147 | KM274731 | KM274585 |

| Vaejovis rossmani | 1532952 | KM274294 | KM274148 | KM274732 | KM274586 |

Table 5

Main statistics of site information per alignment, including parsimony informative sites, (P info) and the concatenated (Conca) alignment of all partitions in a final matrix. The concatenated alignment had 6% missing data.

| Partitions | Terminals/ nucleotide | Site information per alignment | Substitution | |||

| P info | Invariable | Unique | Constant | Model | ||

| 16S | 53/523 | 209 | 285 | 258 | 285 | K3Pu+F+I+G4 |

| 28S | 52/538 | 39 | 494 | 96 | 494 | K2P+I |

| 12S | 51/393 | 153 | 210 | 212 | 210 | TPM2+F+G4 |

| COI | 45/679 | 220 | 420 | 220 | 420 | TIM2+F+G4 |

| Conca | 53/2133 | 621 | 1,409 | 786 | 1,409 | simultaneous |

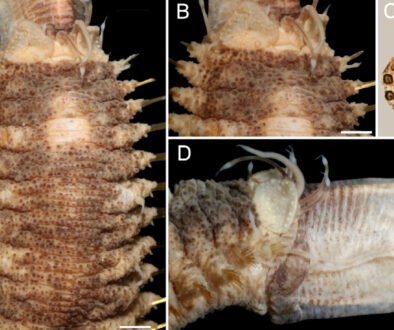

Figure 2. Phylogenetic tree from an analysis of 4 concatenated genetic markers, 3 mitochondrial (12S, 16S, and COI) and 1 nuclear (28S). The topology shows families, subfamilies, and species groups. Numbers beside nodes indicate ultrafast bootstrap/genetic concordance factor/site concordance factor. Colored species represent the 11 species found in our collection within the study area and samples grouping with them distributed inside or outside Colima. Scorpion photos: upper right, Centruroides tecomanus from El Palapo, adult male; middle, Centruroides hirsutipalpus from Sierra de Minatitlán, adult female; lower left, Thorellius intrepidus from El Palapo, adult male.

The Vaejovid clade received full support, except SCF (60%), which included 3 genera: Vaejovis, Mesomexovis, and Thorellius (Fig. 2). The genera occurred in a topology that overall resembles that of González-Santillán and Prendini (2013, 2015); while Vaejovis is a genus within Vaejovinae, Mesomexovis and Thorellius are part of the Syntropinae subfamily. Within Syntropinae, only Thorellius was monophyletic, and T. intrepidus received full support. Additionally, we identified 2 putative new species belonging to the genera Vaejovis and Mesomexovis.

Distributional maps and species geographical ranges. We mined 6,965 records of Mexican scorpions from the InDRE database but retained only 1,000 of the species treated herein. We filtered the records using previously published identified species by specialists and the distribution of the species cited for Colima (González-Santillán & Prendini, 2013, 2018; Lourenço & Sissom, 2000; Ponce-Saavedra et al., 2016; Sissom, 2000).

Figure 3. Map of the west coast of Mexico with georeferenced filtered records from the InDRE database. A, Distribution of Centruroides elegans (circles), records north of Sierra de Manantlán may be misidentifications; B, distribution of Centruroides tecomanus (circles), records in Guerrero (GRO), Guanajuato (GTO), Jalisco (JAL), and Nayarit (NAY) may be misidentifications; Centruroides tecomanus 1 green cross, and Centruroides tecomanus 2 pink crosses. State abbreviations: AUG, Aguascalientes; COL, Colima; MEX, Estado de México; QRO, Querétaro; SLP, San Luis Potosí; ZAC, Zacatecas.

Figure 4. Map of the west coast of Mexico with georeferenced filtered records from the InDRE database and for B additional records from Ponce-Saavedra et al. (2015). A, Distribution of Centruroides infamatus (circles); B, distribution of Centruroides ornatus (circles), our sample in Colima (cross).

Figure 5. Map of the west coast of Mexico with georeferenced filtered records from the InDRE database. A, Distribution of Centruroides hirsutipalpus (red cross), Centruroides sp. 1 (blue cross), Centruroides sp. 2 (pink cross), and Centruroides possanii (green crosses); B, distribution of Mesomexovis aff. occidentalis sequences in this work and a sample from Chamela Jalisco recorded by González-Santillán (2004), conspecific with our samples in green crosses, Vaejovis sp. (mexicanus group) (pink cross).

The distribution of Centruroides species appears to be restricted by physiographical elements. Centruroides elegans and C. tecomanus are restricted to the coastal lands of Jalisco and Colima, respectively (Fig. 3). The Sierra Madre del Sur appears to be the main barrier to the north of their distribution. The records of these species overlap broadly with a visible gap created by the Sierra de Minatitlán (Fig. 3B) either by subsampling or by an effective geographic barrier.

Centruroides ornatus and C. infamatus, on the other hand, are restricted to the Transmexican Volcanic Belt (TVB) (Fig. 4). While the former species has an entire distribution within this province (Fig. 4B), the latter seems to be distributed in patches, one to the north, along the border of the Chihuahuan desert and the TVB, and the second to the south, between the Balsas Depression and the TVB (Fig. 4A).

Centruroides possanii appears to be a microendemic scorpion species component of the fauna restricted to a massive karstic lone mountain, Cerro Grande (González-Santillán et al., 2019). Two putative undescribed species of Centruroides occupy the extreme east and west of the coastal line of Colima, and C. hirsutipalpus appears restricted to the Sierra Minatitlán (Fig. 5A).

Of the vaejovid species, thus far, the only records for Mesomexovis sp. are in Colima, albeit there is one conspecific record in Chamela, Jalisco (González-Santillán, 2004). The putatively undescribed species of Vaejovis appears restricted to Cerro Grande (Fig. 5B), like Centruroides possanii, potentially another microendemic species. Thorellius intrepidus and T. cristimanus are widely distributed within Colima and across the TVB, the Balsas Depression, and the Sierra Madre del Sur (Fig. 6).

Discussion

Of the 2 families found in Colima, Buthidae comprise 7 species of Centruroides,becoming the most diverse (Table 1, Fig. 2). Our multigene analyses suggest that the previously recorded species C. elegans, C. infamatus, and C. limpidus reported by Ponce-Saavedra et al. (2016) might not be part of the scorpion fauna of Colima, as we demonstrate in the following sections.

Figure 6. Map of the west coast of Mexico with georeferenced filtered records from the InDRE database. A, Distribution of Thorellius intrepidus greensquares, our samples in Colima pink crosses; B, distribution of Thorellius cristimanus greensquares, our samples in Colima pink crosses.

Centruroides elegans and C. limpidus were not found in Colima. Centruroides elegans has an obscure taxonomic history. Firstly, its original description is too general and never indicated a precise type locality, but “Mexico” (Fet & Lowe, 2000). Secondly, although some taxonomic works clarified its former subspecies, the nominal taxon identity of C. elegans remains ambiguous. While Lourenço and Sissom (2000) suggested that this species is distributed in Jalisco, later, González-Santillán (2004) concluded that its distributional limits have never been defined with precision. The 2 exemplars of C. elegans collected in Chamela, Jalisco, grouped with members of the elegans group, sisters to C. limpidus from Iguala, Guerrero, and these in turn, were sister to our 2 exemplars identified as Centruroides new sp. 2 11 and 14 from La Central, in the municipality of Manzanillo (Figs. 2). The distributional data from InDRE of C. elegans is limited right at the northern border of Colima, except for 9 records away from that geographic barrier (Fig. 3A), which we hypothesized as a misidentification due to their position outside the Pacific coastline. Our fieldwork produced no sample conspecific to C. elegans but did produce other genetically distant exemplars. Until denser sampling along the northern border of Colima is conducted, we conclude that C. elegans and by corollary C. limpidus might not be part of the scorpion fauna distributed in Colima as suggested by Ponce-Saavedra and Francke (2013) and Ponce-Saavedra et al. (2016).

Centruroides infamatus may not be part of the Colima scorpion fauna. Centruroides infamatus is another obscure taxon with an ambiguous distributional pattern from published data. Despite its inclusion in phylogenetic analyses (Quijano-Ravel et al., 2019; Towler et al., 2001), its taxonomic circumscription and distribution have never been clarified. Among other problems, the original description indicates “type locality unknown” (Fet & Lowe, 2000). Hoffmann (1932) studied the scorpions from Mexico and realized that the specimens from Michoacán agreed with the original description of the species and proposed that its distribution was expanded to Central Mexico from the Pacific Coast in Sinaloa and Colima to Guanajuato. We included 2 exemplars of C. infamatus, 1 from León, Guanajuato (C. infamatus 15 scrp), and 1 terminal from Tandamangapio municipality, Michoacán (C. infamatus LP1822; Esposito et al., 2018). However, the terminal LP1822 grouped with exemplars of C. ornatus (Fig. 2) and Tandamangapio is approximately 16 km from Sahuayo and Jiquilpan, 2 localities recorded in the redescription of C. ornatus (Ponce-Saavedra et al., 2015).

We plotted 612 records from the InDRE database of C. infamatus to compare the distribution of C. ornatus (Fig. 4A). Although northern Michoacán is almost exclusively occupied by C. ornatus, Jalisco and Michoacán present an overlap with C. infamatus (Fig. 4). Additionally, the InDRE database contains records of C. infamatus from Oaxaca, Puebla, Nayarit, Durango, and Sinaloa (not shown), most likely occupied by other species, implying that most records are misidentifications. The species that morphologically could be confused with C. infamatus in the states of Oaxaca and Puebla are C. baergi, C. nigrovariatus, or C. rodolfoi because the overall base color, body size and carapace pigmentation are similar among the species. The same morphological features are present in specimens from Nayarit and Durango, however, the identity of the populations in these two states have never been studied with a molecular approach and may represent a geographically distinct species.

Nevertheless, recently Ponce-Saavedra et al. (2022) described C. baldazoi for Sinaloa, related morphologically with C. infamatus, potentially a species with which it can be mistaken. Although Ponce-Saavedra and collaborators included C. infamatus in the distribution of Sinaloa and Colima, they failed to indicate precise localities. In summary, the distribution of C. infamatus remains unsolved, attested by the wide distribution reported in the InDRE database. Thus, the infamatus species complex requires comprehensive molecular analyses to delimit its taxonomic circumscription and geographical distribution. On the other hand, our samples of C. ornatus 3 and 4 grouped with C. ornatus LP1822 and with C. ornatus 2003 from Morelia, Michoacán (Esposito & Prendini, 2019), forming a monophyletic group (Fig. 2). Since the samples LP1822 and 2003 lie within the area of C. ornatus proposed by Ponce-Saavedra et al. (2015), we concluded that our exemplars are conspecific with C. ornatus and expanded the distribution southwards, drawing a distributional border in northern Colima (Fig. 4B).

In conclusion, we propose that C. infamatus might not be present in Colima, but further sampling and analyses are needed. Despite the morphological similarity between C. infamatus and C. ornatus, our molecular analysis indicates genetic differences and may present a distinctive distributional pattern yet to be drawn with more samples.

Centruroides tecomanus is a species complex. Due to their morphological similarity with C. limpidus, C. tecomanus was described as C. limpidus tecomanus (Hoffmann, 1932), and the author delimited C. tecomanus distribution to the lowlands of Colima and surmised that its distribution extended to the south along the coastline of Michoacán. But, most importantly, Hoffmann mentioned that on the northern coastline, C. elegans substitutes C. tecomanus. In contrast, the distribution recorded in the InDRE database for C. tecomanus implies that these 2 species present a wide area of sympatry on the coast of Jalisco (Fig. 3).

Ponce-Saavedra et al. (2009) proposed C. tecomanus as a “bona fide species” and assumed its distribution includes the coastline of Michoacán, following Hoffmann (1932). In their molecular and morphological analyses, the authors never included exemplars from Tecomán, Colima, the type locality for the species, assuming that the specimens from Michoacán were conspecific with the populations of Tecomán. Furthermore, Quijano-Ravell et al. (2010) extended the distribution of C. tecomanus to 4 localities in Guerrero and a similar number in Jalisco in a montane area.

The phylogenetic tree presented here substantiates 2 clades of C. tecomanus within the monophyletic infamatus species group (Fig. 2). We hypothesize that these clades may represent potentially distinct sympatric species, emphasizing that our topology obtained full support for these clades with multiple samples. Centruroides tecomanus2 appears to be more common and widely distributed in Colima, whereas C. tecomanus1 is less common, with only 2 localities grouped with Centruroides tecomanus 2007 from Michoacán and from the municipality of Comala, Colima, Centruroides tecomanus (Fig. 3B). Our results suggest that the populations distributed in Michoacán may represent a cryptic, undescribed species; consequently, the exemplars reported in Guerrero (Quijano-Ravell et al., 2010) are unlikely to be conspecific with C. tecomanus. The authors’ discovery of new populations in Jalisco and Guerrero were based entirely on their analyses of morphological characters, precisely the most common way of confusing cryptic species.

Considering that the montane border between Colima and Michoacán is occupied by Centruroides romeroi Quijano-Ravell, de Armas, Francke, Ponce-Saavedra, 2019, it is fair to assume that C. tecomanus1 inhabits coastal ranges following the coastline of Michoacán to the Lázaro Cárdenas delta, where it may be substituted by Centruroides bonito Quijano-Ravell, Teruel, Ponce-Saavedra, 2016 or even other undescribed species. The Balsas River has been proposed to be a geographical barrier for several epigean arachnids, such as Amblypygi and Theraphosidae (Mendoza & Francke, 2017; Schramm et al., 2021) and for small mammals (Ruiz-Vega et al., 2018)

Noteworthy is the locality La Central, right on the border between Colima and Jalisco, a few kilometers southeast of the Marabasco River (Fig. 1A), where we collected 3 putatively different species of Centruroides, the 2 morphotypes of C. tecomanus and Centruroides sp. 2, retrieved within the elegans group (Fig. 2). These findings illustrate the complicated patterns of diversification within this buthid genus in Colima. From a taxonomic perspective, if the identity of C. tecomanus is to be clarified, it is now imperative to analyze molecularly exemplars from Tecomán, Colima, which is the type locality of this species.

Thorellius species exhibit a more restricted distribution in Colima. Thorellius intrepidus and T. cristimanus are widely distributed in several states of the Pacific Lowlands (Fig. 6). However, in a recent revision of the genus, 2 species were described, Thorellius wixarika González-Santillán and Prendini, 2018 and Thorellius tekuani González-Santillán and Prendini, 2018 (Fig. 3 of González-Santillán and Prendini, 2018), that are relevant to these analyses. The former occupies the northwestern territory in Nayarit and Jalisco,whereas the latter inhabits the Balsas Depression of Estado de México, Guerrero, and Michoacán. This observation suggests that the InDRE database contains several misidentifications of both T. intrepidus and T. cristimanus. In fact, the T. wixarika and T. tekuani description was in 2018, and the InDRE database is several years older, hence the complete absence of records. Thus, T. intrepidus inhabits Aguascalientes, Colima, Guanajuato, Jalisco, and Michoacán (Fig. 6A); and T. cristimanus, Colima and Jalisco (González-Santillán & Prendini, 2018) (Fig. 6B). From an ecological point of view, we noticed that the InDRE database only has records with elevations below 700 m, implying that these species prefer tropical to subtropical climates in Colima.

González-Santillán (2004) reported Mesomexovis aff. occidentalis as a putative new species for the Biological Station Chamela, Jalisco. Furthermore, González-Santillán and Prendini (2015) conducted a phylogenetic analysis using morphology and mitochondrial and nuclear DNA, resulting in a topology that suggested that this species was not conspecific to Mesomexovis occidentalis, as Williams (1986)identified it. López-Granados (2019) found further morphological evidence to separate this species, but the evidence was never published. The importance of that work is that, for the first time, exemplars of Mesomexovis from Colima that were conspecific with our samples were included in a phylogenetic analysis. Once more, we demonstrate that Mesomexovis sp. 22 is not conspecific with M. occidentalis using molecular evidence, and it requires a formal separation and description (Fig. 2). Unlike Thorellius species in Colima, Mesomexovis is a widespread species inhabiting tropical to montane habitats with a wider range of elevation (Fig. 5B).

The mexicanus group was recently revisited in a monograph with the delimitation of other species groups and the description of 5 new species (Contreras-Félix & Francke, 2019). The paucity of sequences for the mexicanus group in the NCBI database only permitted retrieval of loci for Vaejovis rossmani LP 2027, a species inhabiting the Sierra Madre Oriental in the states of Tamaulipas and Nuevo León and treated in the Contreras-Félix and Francke (2019) monograph. Our analysis retrieved Vaejovis sp. 32 and Vaejovis rossmani LP 2027 together, which suggests membership of the mexicanus group of Vaejovis. Furthermore, Vaejovis sp. 32also matches the morphological diagnosis presented in Contreras-Felix and Francke (2019). Contreras-Félix et al. (2023) recorded Vaejovis santibagnezi Contreras-Felix and Francke, 2019 in Cerro Grande, where we collected our samples (Fig. 5B). However, the authors failed to present morphological evidence to justify this conclusion. We compared our specimens with the geographically closest V. monticola deposited in the CNAN and with V. santibagnezi and found significant morphological differences. Currently, we are preparing a contribution where we propose the description of a new species. Following this idea, we are inclined to think that, like C. possanii, Vaejovis sp. 32 is also microendemic because of its limitation to disperse throughout tropical valleys from the Cerro Grande massif to other mountain ranges. Finally, we submit that such an evident geographical barrier may apply to several epigean, non-volant arthropods such as the scorpions.

Finally, 2 species absent in our fieldwork are Konetontli ilitchi González-Santillán and Prendini 2015 and Vaejovis janssi Williams, 1980. The latter is endemic to the Socorro Island, part of the Revillagigedo Archipelago (Williams, 1980), and K. ilitchi has been found only inside a cave in the vicinity of Coquimatlán, Colima (González-Santillán & Prendini, 2015). These 2 features in the distribution and biology of the species hindered the possibility of collecting and studying them. Future fieldwork may illuminate the taxonomy and distribution of these elusive species. Finally, Vaejovis monticola, another high elevation dweller of the mexicanus species group (Contreras-Felix & Francke 2019) was absent in our collecting trips. Although its type locality cited by Contreras-Felix and Francke (2019) indicates: “Jalisco, northern side of Nevado de Colima” we submit that it may not be on the southern side in Colima, but extensive fieldwork is needed to confirm this hypothesis.

Biogeographical and ecological considerations

There is strong evidence that the ancestors of the North American Centruroides originated in Gondwana and have dispersed to and diversified in that territory via land bridges, vicariance, and rafting over the Atlantic Ocean, over 50 to 20 Mya (Esposito & Prendini, 2019). However, the movement of this genus towards boreal latitudes within North America is not well understood. Although one could suppose that the colonization of such territories appears to be in pulses at different periods due to the overlap in the distribution of the elegans and infamatus species groups, it is beyond the scope of our study to establish a coherent explanation; besides, our data are incomplete to that end. One startling discovery is that the Colima scorpiofauna comprises 7 distinctive, at least genetically, species of Centruroides (Fig. 2). What biotic, abiotic, or ecological factors produce such species diversity? Is it a combination of all these factors? Is it a case of sympatric speciation? Morphologically, it is sometimes difficult to distinguish some of these species. For instance, the 3 species found in La Central were identified initially as C. tecomanus because they exhibit no morphological variation, at least in traditional characters shown in identification keys (Ponce-Saavedra et al., 2016). It is fundamental to conduct morphological studies with this scorpion community to obtain independent information to precisely delimit these species. Unlike other scorpion groups, Centruroides exhibit conservative morphology. For instance, if we compared Centruroides species to species of the Syntropinae subfamily, we find that syntropines are diverse in ecomorphotypic adaptations that promoted morphological diversification (González-Santillán & Prendini, 2013), while in Centruroides, the persistent errant lifestyle maintains morphology without significant variation. It is astonishing to observe, for instance, C. tecomanus living at sea level in tropical deciduous forests and compare it to C. possanii inhabiting pine-oak forests above 2,000 m elevation; as though, the same “Centruroides bauplan” can survive diametrically different environments following a persistent lifestyle. This final assertion leads us to think that the adaptative changes are in the physiology rather than in the morphology of Centruroides.

Thorellius and Mesomexovis (Syntropinae) are substrate-specialists, since the body plan, more robust and armed with setae and spinules on the legs, allow these species to scrape and dig galleries on clayey, fine-grained substrates (González-Santillán & Prendini, 2013, 2018). Such adaptations come with a drawback because the kind of soil restricts the presence of these scorpions; for instance, rocky or shallow soils represent unhospitable habitats for these species. Like other species in the mexicanus group, Vaejovis sp. 32 and Vaejovis monticola Sissom, 1989 are inhabitants of montane habitats within the intricate topography of Colima.

In summary, the scorpion assemblage distributed in Colima includes errant species such as Centruroides without exaggerated adaptations; pelophilous/lapidicolous species such as Thorellius and Mesomexovis, powerful diggers, commonly found underneath rocks or other debris; and scorpions that can be found inside the leaf litter or under nooks of rocks or trees, such as Vaejovis sp. However, it is enigmatic why the Diplocentridae family, well-represented in Mexico, has not been found in Colima. Only in Colima, out of the 3 relatively small states in Mexico, the other 2 being Morelos (Santibáñez-López et al., 2011) and Aguascalientes (Chávez-Samayoa et al., 2022), where similar scorpiofaunistic surveys have been conducted, the genus Diplocentrus is absent. From a biogeographical point of view, if this family is absent in Colima, it is not trivial and requires further investigation.

As a final remark, we hope we have accomplished our aim of urging arachnologists to examine the benefits of local inventories and the potential use of barcodes at the forefront of discovering and documenting local arachnid diversity.

Medical and pharmacological relevance of some scorpions of Colima

From a medical point of view, it is of utmost importance to identify the species of scorpions in an area and to be able to distinguish hazardous from harmless species. Colima is one of the states with the highest incidence rates of mortality and morbidity caused by intoxication by scorpion sting (ISS) (Chowell et al., 2006; González-Santillán & Possani, 2018). By the 1940s, Colima was at the forefront of ISS and deaths in Mexico. However, with the introduction of a safe and effective antivenom in the 1970s, mortality has diminished, although morbidity is still high (González-Santillán & Possani, 2018).

Due to the medical relevance of scorpionism in Mexico, the venom of some buthid scorpions distributed in Colima has been studied extensively (Table 6). We know that mammalian sodium scorpion toxins (NaScTx) are the chief and sometimes most abundant compound responsible for the toxicity of scorpion venom, although potassium, chlorine, and calcium-gated channels, among others, are also affected by toxic peptides (Cid-Uribe et al., 2019; González-Santillán & Possani 2018). Until now, C. hirsutipalpus, C. ornatus, C. possanii, and C. tecomanus have been studied with a proteomic or transcriptomic approach, demonstrating that these venoms are powerful enough to decimate humans (García-Guerrero et al., 2020; García-Villalvazo et al., 2023, Valdez-Velázquez et al., 2016, 2018). Centruroides tecomanus venom contains at least 13 mammalian toxic compounds (Valdez-Velázquez et al., 2016), of which Ct1a is the main mammalian sodium scorpion toxin component, with a molecular weight of 7,591 Da (Martin et al., 1988). The proteomic analysis of C. ornatus toxic components identified 3 major mammalian NaScTx, CO1, CO2, and CO3, with molecular weights of 7,561.2, 7,614.3, and 7,774.9 Da, respectively (García-Guerrero et al., 2020). On the other hand, the published mass fingerprint of C. hirsutipalpus venom has 4 compounds with similar molecular weight to C. tecomanus peptides, suggesting that these species may have similar or identical NaScTx (Valdez-Velázquez et al., 2018). One of the shared compounds found in C. hirsutipalpus corresponds to the molecular weight of Ct1a (Valdez-Velázquez et al., 2013), which means that Ct1a could be responsible for, or at least contribute to, the high toxicity of this species. Although the molecular components with a weight corresponding to the toxic peptides CO1, CO2, and CO3 are not present in C. hirsutipalpus venom, the mass fingerprint of C. tecomanus reported a peptide with similar molecular weight to CO2 toxin present in C. ornatus (Valdez-Velázquez et al., 2013). Our phylogenetic results show that these species belong to the infamatus group, and it is notable that the molecular weight among some toxins is similar. This observation opens the possibility that the toxin diversity of the mammalian NaScTx may have been inherited from a common ancestor. We realize, however, the need for a more in-depth study to unveil the relationship among these toxic peptides to test such a hypothesis. In contrast, a C. possanii crude venom proteomic study resulted in the identification of 18 NaScTx, of which, CpoNatBet09 was identical to Cll2b and Cii1 from C. limpidus and C. infamatus, respectively (Valdez-Velázquez et al., 2013). This example allows us to present the counterpart of the previous one. Centruroides limpidus in our topology grouped with members of the elegans group and C. possanii within the infamatus group (Fig. 2). We can conclude that the exact sequence match between CpoNatBet09 and Cll2b is most likely due to a selective force that produced convergent evolution. Alternatively, this is a deeper inheritance within the ancestors of the infamatus and elegans group.

The comparisons and hypotheses about venom similarities and species assume that all scorpions used to conduct the experiments to obtain the crude venom were correctly identified. However, the discovery of putative species of Centruroides might question some of these results, particularly those of C. tecomanus. The first author has been collaborating to identify most samples of species used in some of the recently published investigation on venom research (Cid-Uribe et al., 2019; García-Guerrero et al., 2020; Romero-Gutiérrez et al., 2017, Valdez-Velázquez et al., 2018, among others). And in some cases, voucher specimens have been deposited in the CNAN, therefore the taxonomic identity for C. hirsutipalpus, C. ornatus, C. possanii can be readily corroborated.

Table 6

Scorpion species with reported LD50 tested on mice at μg/20g mouse weight scale with the named, most abundant, and likely responsible for high toxicity sodium toxins found in the scorpion species of Colima.

| Species | LD50 | NaScTx | Autor |

| Centruroides hirsutipalpus Ponce-Saavedra and Francke, 2009 | 11.7 ± 1.9 | 26 β-NaTx and 5 α-NaTx (proteome) 71 β-NaTx and 16 α-NaTx (transcriptome) | Valdez-Velázquez et al. (2021) |

| Centruroides ornatus Pocock, 1902 | 13.3 ± 1.7 | Beta toxins: Co1, Co2, Co3, Co52 | García-Guerrrero et al. (2020) |

| Centruroides possanii González-Santillán, Galán-Sánchez, Valdez-Velázquez, 2019 | 13.18 ± 0.7 | CpoNatBet09, CpoNatBet14, CpoNatBet35 (Proteome and transcriptome) | García-Villalvazo et al. (2023) |

| Centruroides tecomanus Hoffmann, 1932 | 10.2 ± 0.3 | Beta toxin Ct1a, Ct7, Ct16, Ct17, Ct28, Ct25, Ct6, Ct13, neutoroxin II.22.5 | Valdez-Velázquez et al. (2013, 2016), Ramírez et al. (1988) |

| Thorellius cristimanus Pocock, 1902 | N/A | 10 β-NaTx and 3 α-NaTx (transcriptome) | Romero-Gutiérrez et al. (2017) |

Because vaejovid scorpions exhibit lower toxin potency, proteomic studies are uncommon. However, the study of the crude venom of Thorellius cristimanus under a transcriptomic and proteomic approachidentified160 potential venom peptides (Romero-Gutiérrez et al., 2017). The authors found a great diversity of channel toxins targeting potassium and calcium ion-channels, numerous enzymes, and NDBP. Nevertheless, none of these toxins appear to affect mammals to endanger their life. Noteworthy are the NDBP compounds with antimicrobial activity (Almaaytah et al., 2014), which potentially may be a source for developing novel commercial antibiotics. More recently, Ibarra-Vega et al. (2023) reported finding the neurotransmitter serotonin and 2 derived or intermediate indoles of serotonin: N-methylserotonin, and bufotenidine. Although serotonin has been reported in other scorpions and the sea snail genus Conus, the other indoles represent the first report in scorpions. The authors proposed that the 3 components are involved in defense and probably prey submission because they produce extreme pain in the victim. Furthermore, N-methylserotonin and bufotenidine showed a similar affinity for serotonin cellular receptors, implying a role in the effect of this neurotransmitter, and thus, it showed promising medical applications.

Integrating taxonomic, distributional, and in our case venom diversity within local scorpion faunas is an interdisciplinary topic uncommon in the literature (Brito & Borges, 2015; Cao et al., 2014), although this exercise has been done in Mexico before (Santibáñez-López et al., 2015). This multidisciplinary work took advantage of a reciprocal illumination exercise. This short synthesis of the diversity of venoms of scorpion of Colima revealed the potential of toxins to be part of the evidence to identify and delimit species (Schaffrath et al., 2018). Moreover, the synthesis provided a glance of the evolution of venoms not only for the medically prominent species of Centruroides but also for vaejovid scorpion species. From the experimental discipline, we learned that it is paramount to maintain vouchers after biochemical or physiological experiments to track down the original material and keep up with the dynamics of taxonomy, a tool requiring empirical information to permit the identification of species to validate past, present, and future discoveries in other biological disciplines.

Acknowledgments

We thank the University of Colima students and Josué López Granados (Facultad de Ciencias, UNAM) for their assistance in collecting scorpions throughout the state of Colima. JICU thanks Conahcyt for granting a postdoctoral scholarship (512560). Collection permits granted by Semarnat included SGPA/DGVS/12063/15, SGPA/DGVS/02139/2022, and FAUT-0305. Finally, we are grateful to the Associate Editor and two reviewers for improving an early version of the manuscript, particularly to Andrés Ojanguren-Afilastro for his critical reading.

References

Almaaytah, A., & Albalas, Q. (2014). Scorpion venom peptides with no disulfide bridges: a review. Peptides, 51, 35−45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.peptides.2013.10.021

Baldazo-Monsivaiz, J. G., Ponce-Saavedra, J., & Flores-Moreno, M. (2012). Los alacranes (Arachnida: Scorpionida) de importancia médica del estado de Guerrero, México. Dugesiana, 19, 143−150.

Baldazo-Monsivaiz, J. G., Teruel, R., Cortés-Guzmán, A. J., & Canché-Aguilar, I. (2017). Los escorpiones (Arachnida: Scorpiones) del municipio de Chilpancingo de los Bravo, estado de Guerrero, México Entomología Mexicana, 4, 21−27.

Baldazo-Monsivaiz, J. G., Teruel, R., Cortés-Guzmán, A. J., Sánchez-Arriaga, J., López-Flores, M., Reyes-Castelán, A. et al. (2016). Los escorpiones (Arachnida: Scorpiones) del municipio de Taxco de Alarcón, del estado de Guerrero, México. Entomología Mexicana, 3, 75−80.

Bolaños, L. M., Rosenblueth, M., de Lara, A. M., Migueles-Lozano, A., Gil-Aguillón, C., Mateo-Estrada, V. et al. (2019). Cophylogenetic analysis suggests cospeciation between the Scorpion Mycoplasma Clade symbionts and their hosts. Plos One, 14, e0209588 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0209588

Brito, G., & Borges, A. (2015). A checklist of the scorpions of Ecuador (Arachnida: Scorpiones), with notes on the distribution and medical significance of some species. Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins Including Tropical Diseases, 21, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1186%2Fs40409-015-0023-x

Cao, Z., Di, Z., Wu, Y., & Li, W. (2014). Overview of scorpion species from China and their toxins. Toxins, 6, 796–815. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins6030796

Cid-Uribe, J. I., Meneses E. P., Batista, C. V. F., Ortiz, E., & Possani, L. D. (2019). Dissecting toxicity: The venom gland transcriptome and the venom proteome of the highly venomous scorpion Centruroides limpidus (Karsch, 1879). Toxins, 247, 1−21. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins11050247

Contreras-Félix, G. A., & Francke, O. F. (2019). Taxonomic revision of the “mexicanus” group of the genus Vaejovis C. L. Koch, 1836 (Scorpiones: Vaejovidae). Zootaxa, 4596, 1−100. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4596.1.1

Contreras-Félix, G. A., del Pozo, O. G., & Navarrete-Heredia, J. L. (2023). A new species of Vaejovis from the mountains of west Mexico (Scorpiones: Vaejovidae). Dugesiana, 30, 229−245. https://doi.org/10.32870/dugesiana.v30i2.7306

Chávez-Samayoa, F., Díaz-Plascencia, J. E., & González-Santillán, E. (2022). Two new species of Vaejovis (Scorpiones: Vaejovidae) belonging to the mexicanus group from Aguascalientes, Mexico, with comments on the homology and function of the hemispermatophore. Zoologischer Anzeiger, 298, 148–169. https://doi.org/10.

1016/j.jcz.2022.04.005

Chowell, G., Díaz-Dueñas, P., Bustos-Saldaña, R., Alemán-Mireles, A., & Fet, V. (2006). Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of scorpionism in Colima, Mexico (2000-2001). Toxicon, 47, 753–758. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxicon.2006.02.004

Esposito, L. A., & Prendini, L. (2019). Island ancestors and New World biogeography: a case study from the scorpions (Buthidae: Centruroidinae). Scientific Reports, 9, 3500. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-33754-8

Fet, V., Graham, M. R., Blagoev, G., Karataş, A., & Karataş, A. (2016). DNA barcoding indicates hidden diversity of Euscorpius (Scorpiones: Euscorpiidae) in Turkey. Euscorpius, 216, 1–13.

Fet, V., Graham, M. R., Webber, M. M., & Blagoev, G. (2014). Two new species of Euscorpius (Scorpiones: Euscorpiidae) from Bulgaria, Serbia, and Greece. Zootaxa, 3894, 83–105. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3894.1.7

Fet, V., & Lowe G. (2000). Family Buthidae C. L: Koch, 1837. In V. Fet, W. D. Sissom, G. Lowe, & M. E. Braunwalder (Eds.), Catalog of the scorpions of the World (1758–1998) (pp. 54–286). New York: New York Entomological Society.

Folmer, O., Black, M., Hoeh, W., Lutz, R., & Vrijenhoek, R. (1994). DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Molecular Marine Biology and Biotechnology, 3, 294–299.

García-Guerrero, I. A., Cárcamo-Noriega, E., Gómez-Lagunas, F., González-Santillán, E., Zamudio, F. Z., Gurrola, G. B. et al. (2020). Biochemical characterization of the venom from the Mexican scorpion Centruroides ornatus, a dangerous species to humans. Toxicon, 15, 27–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxicon.2019.11.004

García-Villalvazo, P. E., Jiménez-Vargas, J. M., Lino-López, G. J., Meneses, E. P., Bermúdez-Guzmán, M. J., Barajas-Saucedo, C. E. et al. (2023). Unveiling the protein components of the secretory-venom gland and venom of the scorpion Centruroides possanii (Buthidae) through omic technologies. Toxins, 15, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins15080498

Goodman, A. M., Prendini, L., & Esposito, L. A. (2021). Systematics of the arboreal Neotropical ‘thorellii’ clade of Centruroides bark scorpions (Buthidae) and the efficacy of mini-barcodes for museum specimens. Diversity, 13, 441. https://doi.org/10.3390/d13090441

Goodman, A. M., Prendini, L., Francke, O. F., & Esposito, L. A. (2021). Systematic revision of the arboreal neotropical “thorellii” clade of Centruroides Marx, 1890, bark scorpions (Buthidae C. L. Koch, 1837) with descriptions of six new species. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, 452, 1–92.

González-Santillán, E. (2004). Diversidad, taxonomía y hábitat de alacranes. In A. N. García, & R. Ayala (Eds.), Artrópodos de Chamela (pp. 25–35). México D.F.: Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

González-Santillán, E., Galán-Sánchez, M. A., & Valdez-Velázquez, L. L. (2019). A new species of Centruroides (Scorpiones, Buthidae) from Colima, Mexico. Comptes Rendus Biologies, 342, 9–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crvi.2019.10.002

González-Santillán, E., & Possani, L. D. (2018). North American scorpion species of public health importance with a reappraisal of historical epidemiology. Acta Tropica, 187, 264–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2018.08.002

González-Santillán, E., & Prendini, L. (2013). Redefinition and generic revision of the North American vaejovid scorpion subfamily Syntropinae Kraepelin, 1905, with descriptions of six new genera. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, 382, 1–71.

González-Santillán, E., & Prendini, L. (2015). Phylogeny of the North American vaejovid scorpion subfamily Syntropinae Kraepelin, 1905, based on morphology, mitochondrial and nuclear DNA. Cladistics, 31, 341–405. https://doi.org/10.1111/cla.12091

González-Santillán, E., & Prendini, L. (2018). Systematic revision of the North American Syntropine Vaejovid scorpion genera Balsateres, Kuarapu, and Thorellius, with descriptions of three new species. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, 420, 1–81. https://doi.org/10.1206/0003-0090-420.1.1

Hoang, D. T., Chernomor, O., Haeseler, A. von, Minh, B. Q., & Vinh, L. S. (2018) UFBoot2: Improving the ultrafast bootstrap approximation. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 35, 518–522. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msx281

Hoffmann, C. C. (1932). Monografías para la entomología médica de México. Monografía Núm. 2. Los scorpiones de Mexico. Segunda parte, Buthidae. Anales del Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 3, 243–361.

Huerta-Jiménez, H. (2018). Actualización de la Colección de Artrópodos con importancia médica (CAIM), Laboratorio de Entomología, InDRE. Version 1.5. Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y uso de la Biodiversidad.

Ibarra-Vega, R., Jiménez-Vargas, J. M., Pineda-Contreras, A., Martínez-Martínez, F. J., Barajas-Saucedo, C. E., García-Ortega, H. et al. (2023). Indolealkylamines in the venom of the scorpion Thorellius intrepidus. Toxicon, 233, 107232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxicon.2023.107232

Jarvis, A., Reuter, H. I., Nelson, A. & Guevara, E. (2008). Hole-filled seamless SRTM data V4, International Centre for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT), available from http://srtm.csi.cgiar.org

Kalyaanamoorthy, S., Minh, B. Q., Wong, T. K. F., Haeseler, A. von, & Jermiin, L. S. (2017). ModelFinder: fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nature Methods, 14, 587–589. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.4285

Katoh, K., Rozewicki, J., & Yamada, K. D. (2019). MAFFT online service: multiple sequence alignment, interactive sequence choice and visualization, Briefings in Bioinformatics, 20, 1160–1166. https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbx108

Kocher, T. D., Thomas, W. K., Meyer, A., Edwards, S. V., Paabo, S., Villablanca, F. X. et al. (1989). Dynamics of mitochondrial DNA evolution in animals: amplification and sequencing with conserved primers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 86, 6196–6200. https://doi.org/10.1073%2Fpnas.86.16.6196

Kuraku, S., Zmasek, C. M., Nishimura, O., & Katoh, K. (2013). aLeaves facilitates on-demand exploration of metazoan gene family trees on MAFFT sequence alignment server with enhanced interactivity, Nucleic Acids Research, 41, W22–W28. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkt389

López-Granados, J. (2019). Análisis filogenético del complejo de especies occidentalis del género Mesomexovis González-Santillán y Prendini, 2013 (Scorpiones: Vaejovidae) basado en evidencia morfológica (Tesis). Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. CDMX.

Lourenço, W. R., & Sissom, W. D. (2000). Scorpiones. In B. J. Llorente, E. González, & N. Papavero (Eds.), Biodiversidad, taxonomía y biogeografía de artrópodos de México: hacia una síntesis de su conocimiento (pp. 115–135). Ciudad de México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Maddison, W. P., & Maddison, D. R. (2023). Mesquite: a modular system for evolutionary analysis. Version 3.81. http://www.mesquiteproject.org

Martin, B. M., Carbone, E., Yatani, A., Brown, A. M., Ramírez, A. N., Gurrola, G. B. et al. (1998). Amino acid sequence and physiological characterization of toxins from the venom of the scorpion Centruroides limpidus tecomanus Hoffmann. Toxicon, 26, 785–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/0041-0101(88)90319-4

Mendoza, J., & Francke, O. (2017). Systematic revision of Brachypelma red-kneed tarantulas (Araneae: Theraphosidae), and the use of DNA barcodes to assist in the identification and conservation of CITES-listed species. Invertebrate Systematics, 31, 157–179. https://doi.org/10.1071/IS16023

Minh, B. Q., Hahn, M. W., & Lanfear, R. (2020). New methods to calculate concordance factors for phylogenomic datasets. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 37, 2727–2733. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msaa106

Morrone, J. (2019). Regionalización biogeográfica y evolución biótica de México: encrucijada de la biodiversidad del Nuevo Mundo. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 90, e902980. https://doi.org/10.22201/ib.20078706e.2019.90.2980

Morrone, J., Escalante, T., & Rodríguez-Tapia, G. (2017). Mexican biogeographic provinces: map and shapefiles. Zootaxa, 4277, 277–279. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4277.2.8

Nguyen, L. T., Schmidt, H. A., Haeseler, A. von, & Minh, B. Q. (2015). IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum likelihood phylogenies. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 32, 268–274. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msu300

Nunn, G. B., Theisen, B. F., Chirstensen, B., & Arctander, P. (1996). Simplicity-correlated size growth of the nuclear 28S ribosomal RNA D3 expansion segment in the crustacean order Isopoda. Journal of Molecular Evolution, 42, 211–223. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02198847

Podnar, M., Grbac, I., Tvrtković, N., Hörweg, C., & Haring, E. (2021). Hidden diversity, ancient divergences, and tentative Pleistocene microrefugia of European scorpions (Euscorpiidae: Euscorpiinae) in the eastern Adriatic region. Journal of Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Research, 59, 1824–1849. https://doi.org/10.1111/jzs.12562

Ponce-Saavedra, J., & Francke, O. F. (2013). Clave para la identificación de especies de alacranes del género Centruroides Marx 1890 (Scorpiones: Buthidae) en el Centro Occidente de México. Biológicas, 15, 52–62.

Ponce-Saavedra, J. y Francke, O. F. (2019). Una especie nueva de alacrán del género Centruroides (Scorpiones: Buthidae) del noroeste de México. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad,

90, e902660. https://doi.org/10.22201/ib.20078706e.2019.

90.2660

Ponce-Saavedra, J., Francke, O. F., Cano-Camacho, H., & Hernández-Calderón, E. (2009). Evidencias morfológicas y moleculares que validan como especie a Centruroides tecomanus (Scorpiones, Buthidae). Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 80, 71–84. https://doi.org/10.22201/ib.20078706e.2009.001.585

Ponce-Saavedra, J., Francke, O. F., Quijano-Ravell, A. F., & Santillán, R. C. (2016). Alacranes (Arachnida: Scorpiones) de importancia para la salud pública de México. Folia Entomológica Mexicana, 2, 45–70.

Ponce-Saavedra, J., Jiménez, M. L., Quijano-Ravell, A. F., Vargas-Sandoval, M., Chamé-Vázquez, D., Palacios-Cardiel, C. et al. (2023). The Fauna of Arachnids in the Anthropocene of Mexico, Chapter 2(pp. 18–39) In R. W. Jones, C. P. Ornelas-García, R. Pineda-López, & F. Álvarez (Eds.), Mexican fauna in the Anthropocene. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-17277-9

Ponce-Saavedra, J., Linares-Guillén, J. W., & Quijano-Ravell, A. F. (2022). Una nueva especie de alacrán del género Centruroides Marx (Scorpiones: Buthidae) de la costa Noroeste de México. Acta Zoológica Mexicana (nueva serie), 38, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.21829/azm.2022.3812517

Ponce-Saavedra, J., Quijano-Ravell, A. F., Teruel, R., & Francke, O. F. (2015). Redescription of Centruroides ornatus Pocock, 1902 (Scorpiones: Buthidae), a montane scorpion from Central Mexico. Revista Ibérica de Aracnología, 27, 81–89.

Prendini, L., Weygoldt, P., & Wheeler, W. C. (2005). Systematics of the Damon variegatus group of African whip spiders (Chelicerata: Amblypygi): evidence from behaviour, morphology and DNA. Organisms Diversity & Evolution, 5, 203–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ode.2004.12.004

Quijano-Ravell, A. F., De Armas, L. F., Francke, O. F., & Ponce-Saavedra, J. (2019). A new species of the genus Centruroides Marx (Scorpiones, Buthidae) from western Michoacán state, México using molecular and morphological evidence. Zookeys, 859, 31–48. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.859.33069

Quijano-Ravell, A. F., Ponce-Saavedra, J., Francke, O. F., & Villaseñor-Ramos. M. A. (2010). Nuevos registros y distribución actualizada de Centruroides tecomanus Hoffmann, 1931 (Scorpiones: Buthidae). Ciencia Nicolaita, 52, 179–189.

QGIS.org. (2021). QGIS Geographic Information System. Open-Source Geospatial Foundation Project. http://qgis.org

Ramírez-Ruiz, J. J., & Bretón-González, M. (2016). Fisiografía y geología. In La Biodiversidad en Colima. Estudio de estado (Eds.) (pp. 25–31). México D.F.: Conabio.

Romero-Gutiérrez, T., Peguero-Sánchez, E., Cevallos, M. A., Batista, C. V. F., Ortiz, E., & Possani L. D. (2017). A deeper examination of Thorellius atrox scorpion venom components with omics technologies. Toxins, 9, 399. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins9120399

Ruiz-Vega, M. L., Hernández-Canchola, G., & León-Paniagua, L. (2018). Molecular systematics and phylogeography of the endemic Osgood’s deermouse Osgoodomys banderanus (Rodentia: Cricetidae) in the lowlands of western Mexico. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 127, 867–877. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2018.06.034

Santibáñez-López, C. E., Francke, O. F., & Córdova-Athanasiadis, M. (2011). The genus Diplocentrus Peters (Scorpiones: Diplocentridae) in Morelos, Mexico. Revista Ibérica de Aracnología, 19, 3–3.

Santibáñez-López, C. E., Francke, O. F., & Prendini, L. (2014). Phylogeny of the North American scorpion genus Diplocentrus Peters, 1861 (Scorpiones: Diplocentridae) based on morphology, nuclear and mitochondrial DNA. Arthropod Systematics & Phylogeny, 72, 257–279. https://doi.org/10.3897/asp.72.e31789

Santibáñez-López, C., Francke, O., Ureta, C., & Possani, L. (2015). Scorpions from Mexico: from species diversity to venom complexity. Toxins, 8, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins8010002

Schaffrath, S., & Predel, R. (2014). A simple protocol for venom peptide barcoding in scorpions. EuPA Open Proteomics, 3, 239–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euprot.2014.02.017

Schramm, F. D., Valdez-Mondragón, A., & Prendini, L. (2021). Volcanism and palaeoclimate change drive diversification of the world’s largest whip spider (Amblypygi). Molecular Ecology, 30, 2872–2890. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.15924

Simon, C., Frati, F., Beckenbach, A., Crespi, B., Liu, H., & Flook, P. K. (1994). Evolution, weighting, and phylogenetic utility of mitochondrial gene sequences and a compilation of conserved polymerase chain reaction primers. Annals of the Entomological Society of America, 87, 651–700. https://doi.org/10.1093/aesa/87.6.651

Sissom, W. D. (2000). Family Vaejovidae Thorell, 1876. In V. Fet, W. D. Sissom, G. Lowe, & M. E. Braunwalder (Eds.), Catalog of the scorpions of the World (1758–1998) (pp. 503–553). New York: New York Entomological Society.

Towler, W. I. I., Ponce-Saavedra, J., Gantenbein, B., & Fet, V. (2001). Mitochondrial DNA reveals a divergent phylogeny in tropical Centruroides (Scorpiones: Buthidae) from Mexico. Biogeographica, 77, 157–172.

Valdez-Velázquez, L. L., Olamendi-Portugal, T., Restano-Cassulini, R., Zamudio, F. Z., & Possani, L. D. (2018). Mass fingerprinting and electrophysiological analysis of the venom from the scorpion Centruroides hirsutipalpus (Scorpiones: Buthidae). Journal of Venom Animal Toxins Including Tropical Diseases, 24, 17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40409-018-0154-y

Valdez-Velázquez, L. L., Quintero-Hernández, V., Romero-Gutiérrez, M. T., Coronas, F. I., & Possani, L. D. (2013). Mass fingerprinting of the venom and transcriptome of venom gland of scorpion Centruroides tecomanus. Plos One, 8, e66486. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0066486

Valdez-Velázquez L. L., Romero-Gutiérrez M. T., Delgado-Enciso, I., Dobrovinskaya, O., Melnikov, V., Quintero-Hernández, V. et al. (2016). Comprehensive analysis of venom from the scorpion Centruroides tecomanus reveals compounds with antimicrobial, cytotoxic, and insecticidal activities. Toxicon, 118, 95-103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxicon.2016.04.046

Williams, S. C. (1980). Scorpions of Baja California, Mexico and adjacent islands. Occasional Papers of the California Academy of Sciences, 135, 1–127.

Williams, S. C. (1986). A new species of Vaejovis from Jalisco, Mexico (Scorpiones: Vaejovidae). Pan-Pacific Entomologist, 62, 355–358.