Angélica Rodríguez-Cifuentes a, Jovana M. Jasso-Martínez a, Valeria B. Salinas-Ramos a, Juan José Martínez b, Alejandro Zaldívar-Riverón a, *

a Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Biología, Colección Nacional de Insectos, Tercer Circuito Exterior s/n, Ciudad Universitaria, Coyoacán, 04510 Mexico City, Mexico

b Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET), Departamento de Ciencias Biológicas, Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Universidad de La Pampa, Uruguay 151, L6300LB, Santa Rosa, La Pampa, Argentina

*Corresponding author: azaldivar@ib.unam.mx (A. Zaldívar-Riverón).

Received: 17 November 2023; accepted: 15 March 2024

Abstract

Galls are an abnormal growth of plant tissue in response to the presence generally of an inducing insect, which ensures food and protection during specific periods of its life. Besides gall formers, a vast community of arthropods are associated with galls, including inquilines and parasitoids. Few studies have assessed the gall diversity and its associated insect community in Neotropical vascular plants. Here, we characterised the leaf gall diversity of Coccoloba barbadensis Jacq. (Polygonaceae) in a Mexican tropical dry forest, as well as their associated entomofauna based on morphology and DNA barcoding. Five different gall morphotypes were observed during both dry (April-June) and rainy (November) seasons. A total of 34 and 38 species of Diptera, Hymenoptera, Coleoptera, and Lepidoptera were delimited with the 2% divergence criterion and the GMYC model, respectively. Based on our rearing observations and literature, Cecidomyiidae (Diptera) species might induce all leaf gall morphotypes, whereas hymenopterans are represented by parasitoid and probably inquiline species of the families Braconidae, Eulophidae, Eupelmidae, Platygastridae and Torymidae. Our results highlight the importance of performing integrative species delineation studies of arthropods present in galls to have an accurate knowledge of their diversity and trophic interactions.

Keywords: Trophic interactions; Host; Parasitoid; DNA barcode; Gall former

© 2024 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Biología. Este es un artículo Open Access bajo la licencia CC BY-NC-ND

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Diversidad de agallas de hojas en la planta neotropical

Coccoloba barbadensis (Polygonaceae) y riqueza de especies de sus insectos asociados

Resumen

Las agallas son un crecimiento anormal de tejido de plantas por la presencia de un insecto inductor que le asegura alimento y protección durante periodos específicos. Además de los formadores de agallas, una vasta comunidad de artrópodos está también asociada, incluidos inquilinos y parasitoides. Pocos estudios han evaluado la diversidad de agallas y su comunidad de insectos en plantas vasculares neotropicales. Aquí se caracteriza la diversidad de agallas foliares de Coccoloba barbadensis Jacq. (Polygonaceae) en un bosque seco tropical mexicano, así como su entomofauna asociada basada en morfología y el código de barras del DNA. Se observaron 5 morfotipos de agallas durante las temporadas seca (abril-junio) y lluviosa (noviembre). Se delimitó un total de 34 y 38 especies de Diptera, Hymenoptera, Coleoptera y Lepidoptera con el criterio de divergencia de 2% y el modelo GMYC, respectivamente. Según las observaciones y datos de literatura, especies de Cecidomyiidae (Diptera) inducen todos los morfotipos de agallas, y los himenópteros están representados por especies parasitoides y probablemente inquilinas de las familias Braconidae, Eulophidae, Eupelmidae, Platygastridae y Torymidae. Los resultados resaltan la importancia de estudios integradores para la delimitación de especies de artrópodos de agallas para tener conocimiento preciso de su diversidad e interacciones tróficas.

Palabras clave: Interacciones tróficas; Hospedero; Parasitoide; Código de barras del DNA; Formador de agallas

Introduction

Ecological interactions among species form the basis of ecosystem functioning and underlie evolutionary and ecological principles of conservation biology (Clare et al., 2013). Three types of biological networks have been defined based on interactions and the types of organisms involved (Ings et al., 2009): traditional or antagonistic food webs (e.g., predators and prey/food webs), mutualistic networks (e.g., seed dispersal and pollination), and host-parasitoid networks. The study of these biological networks provides a whole ecosystem outline to examine the effects of biodiversity loss on communities and ecosystem functions (Ings et al., 2009).

Understanding the links of a network relies on the idea that descriptors of interaction structure are unbiased and accurate (Wirta et al., 2014). In practice, however, networks are difficult to create, especially using traditional methods. Taxonomic resolution and the methodology employed to delimit species are crucial to reconstruct interaction structure (Paine, 1980; Kaartinen & Roslin, 2011). If the links are poorly resolved and multiple taxa are inadvertently grouped within the nodes of a web, there is a risk of misunderstanding its composition and thus its functioning system (Kaartinen & Roslin, 2011; Wirta et al., 2014).

An astonishing number of arthropod taxa depend on plants as food resources or closely interact with them. Among these are species that form enclosed structures known as galls (Mani, 1964; Raman, 2011). These structures are defined as abnormal growth of tissues of host plants in response to the activity or presence of an inducing organism (Nieves-Aldrey, 1998; Price, 2005; Redfern et al., 2002). Galls can be found in several plant structures such as flowers, roots, fruits, leaves, thorns, or stems. Arthropods induce galls to ensure food resources and to protect themselves against predators or unfavourable environmental conditions during certain periods of their life cycle (Nieves-Aldrey, 1998; Raman & Withers, 2003).

Gall induction in insects mainly occurs in species of Hymenoptera, but also in species of Diptera, Hemiptera and Thysanoptera, and less frequently in Coleoptera and Lepidoptera (Raman, 2011). Besides gall formers, there is an intricate community of different insect species that also are associated with galls, including inquilines (i.e., species that develop within galls made by other insects and feed on plant tissue), parasitoids of gall formers and inquilines and hyperparasitoids (i.e., parasitoids of other parasitoid species) (Forbes et al., 2015). Despite the great ecological importance of galls in most terrestrial ecosystems due to the extraordinary arthropod diversity that they comprise, to date, most of this species diversity and the interactions that are involved are largely unknown, especially in tropical and subtropical regions.

In recent years, molecular techniques have provided detailed analyses of interaction reconstruction, allowing precise identification of members of natural communities and the structure of networks (Clare et al., 2013; Kaartinen et al., 2010; Wirta et al., 2014). The DNA barcoding locus, a fragment of the cytochrome oxidase I (COI) mitochondrial DNA gene, is the most employed genetic marker for species discrimination of closely related animal species (Hebert et al., 2003; Ratnasingham & Hebert, 2013). This marker is a valuable tool for the rapid identification of megadiverse, poorly known taxa (Hebert et al., 2003). Moreover, it allows the association of morphologically distinct semaphoronts (e.g., insect larvae and adults; Yeo et al., 2018) and sexes of the same species (e.g., Sheffield et al., 2009).

Coccoloba barbadensis is a widely distributed Neotropical vascular plant species that in Mexico occurs in tropical regions from central to southeast Mexico (Howard, 1959). In this study, the diversity of galls on the leaves of the vascular plant C. barbadensis Jacq. (Polygonaceae) in a Mexican tropical dry forest was characterised and their associated entomofauna assessed using both morphological and DNA barcoding data. We highlight the necessity to perform integrative species delimitation studies of arthropods present in galls, particularly in the tropics, to have a more accurate knowledge of their species richness.

Materials and methods

The study was conducted in the Biological Station of Chamela (EBCH), Jalisco, Mexico (19’29” N, 105’01” W; Noguera et al., 2002), owned by the Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. The Chamela region is mainly composed of tropical dry forest and is characterised by having 85% of the ~ 750 mm of yearly rain from July to November and a mean annual temperature of 24.9 °C (14.8-32 °C) (Méndez-Alonzo et al., 2013). Tropical dry forests frequently show extreme changes in the physiognomy and available resources during the rainy and dry seasons, therefore altering the composition and diversity of their fauna (Razo-González et al., 2014).

We carried out 2 collecting trips at the EBCH, one during the dry (from March to June 2013) and the other during the rainy season (November 2013). Fifteen trees belonging to C. barbadensis were located and marked, all of which were situated near seasonal streams. We collected 1-5 leaves with galls from different parts of the selected trees. By in situ photographs we documented the presence/absence of galls for each tree, as well as general leaf features such as colour and size. The main gall’s features, including shape, size, colour, and pubescence, and the number of all collected galls present on the leaves were classified by morphotypes and recorded.

The levels of infestation, presence, and type of galls were weekly recorded, and the total number of galls per leaf was recorded. Galls were subsequently dissected or maintained in the laboratory to rear their insects. All reared insects were preserved in 96% ethanol and stored at -20 °C.

All collected insects were sorted out into adults, larvae, or pupae, and were counted and discriminated into morphospecies with a Zeiss™ Stemi DV4 (Göttingen, Germany) stereomicroscope. Larvae and adults of Hymenoptera were identified to order and genus level, respectively, using the specialised literature. Larvae and adults of Diptera and larvae of Coleoptera and Lepidoptera could only be identified to family and order level, respectively.

Gall abundance

The relationship between both the total number of collected galls and the average number of each gall morphotype concerning the time of collection during the dry season was evaluated using a simple linear regression with the statistical program R (R Core Team, 2013). Data of rainy season were not statistically analysed, since there were not enough samples to perform statistical tests. The insect family frequency throughout the sampled period was also analysed and then a canonical correspondence analysis to characterise the association between insect species and gall morphotypes with the program Statistica version 10 (StatSoft, Inc., 2011).

Molecular data

It is widely recognised that species misidentifications have negative consequences in ecological studies (Bortolus, 2008; Vink et al., 2012). Species delimitation and identification can be considerably improved using morphology-based taxonomy coupled with DNA sequence data (Dexter et al., 2010). Some representative specimens of most identified morphospecies were molecularly characterised generating for them DNA sequences of a fragment belonging to the barcoding locus COI mitochondrial gene (Hebert et al., 2003). This gene marker has been proved to be a generally reliable tool for the rapid delimitation of animal species, including insects (Hebert et al., 2003, 2004).

The genomic DNA from 1-6 specimens belonging to each discriminated insect morphotype was extracted. DNA extractions were conducted with the kit Tissue and tissue plus SV mini (Gene All®, Seoul, Korea), by placing each individual in 20 μl of proteinase K and 200 μl of TL Buffer, at 56 °C for 8 h. The larvae bodies were completely degraded after digestion, whereas the pupae exoskeletons and the adult individuals were subsequently washed with distilled water, placed back in 96% ethanol, and stored at -20 °C until they were mounted and labelled.

The COI fragment was amplified using the LCO1460/HCO2198 primers (Folmer et al., 1994). The following PCR conditions were used: initial denaturation at 95 ºC for 3 min, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 40 s, 40 s annealing at 45 °C, 40 s extension at 72 °C, and a final extension at 72 °C for 7 min. PCRs were prepared in a final volume of 15 μl of reaction mixture, which included 1.5 μl of 10X buffer, 0.75 μl of MgCl 2 (50 mM), 0.3 μl of dNTPs (10 mM), 0.24 μl of each primer (10 μM), 0.12 μl of Taq Platinum polymerase (Invitrogen®, Carlsbad, CA, USA), 8.85 μl of water and 3 μl of DNA template.

Unpurified PCR products were sent for DNA sequencing to the High-Throughput Genomics Unit of the University of Washington, Seattle, USA (http://www.htseq.org/). Sequences were edited and aligned manually based on their translated amino acids and compared individually with the sequences available in GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank) using the BLAST online program (Altschul et al., 1990; http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi).

DNA sequence-based species delimitation of dipterans and hymenopterans was carried out separately with the barcoding locus using 2 approaches, the General Mixed Yule Coalescence (GMYC) model (Pons et al., 2006) and the 2% genetic divergence criterion (Hebert et al., 2003).

The GMYC model requires an ultrametric tree, which was obtained with the program BEAST version 1.7.4 (Drummond et al., 2012), running the analysis for 10 million generations, sampling trees every 1,000 generations, using an uncorrelated lognormal clock and a coalescent tree prior. Only 1 partition was considered, which used the GTR+Γ+I evolutionary model. The duplicated haplotypes from the matrix were removed using the program Collapse 1.2 (Posada, 2004). The first 2,500 trees were eliminated as “burn-in” and the remaining trees were used to reconstruct a maximum clade credibility tree with the program TreeAnnotator version 1.7.4 (part of the BEAST 1.7.4 package). The GMYC model implemented in the SPLITS package (http://r-forge.r-project.org/projects/splits/) was performed with the R program version 2.10.1 (R core Team, 2021).

For the 2% divergence criterion, the allocation of molecular taxonomic units (Hebert et al., 2003) was made depending on the percentage of similarity in the genetic distances of the analysed sequences. If the percentage was less than 2, those MOTUs were considered to belong to the same barcoding species. Uncorrected COI divergences were obtained with the program PAUP* version 4.0 (Swofford, 2003). A Neighbor-Joining (NJ) distance tree for Diptera and Hymenoptera was reconstructed separately with the above program to visualise the genetic distances obtained. The trees obtained from 2 species delineation approaches were visualised with the program Figtree version 1.4.4 (Bouckaert et al., 2014).

Results

Description and abundance of galls

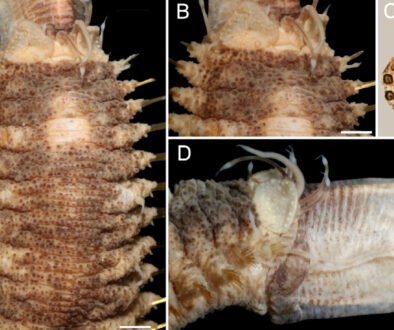

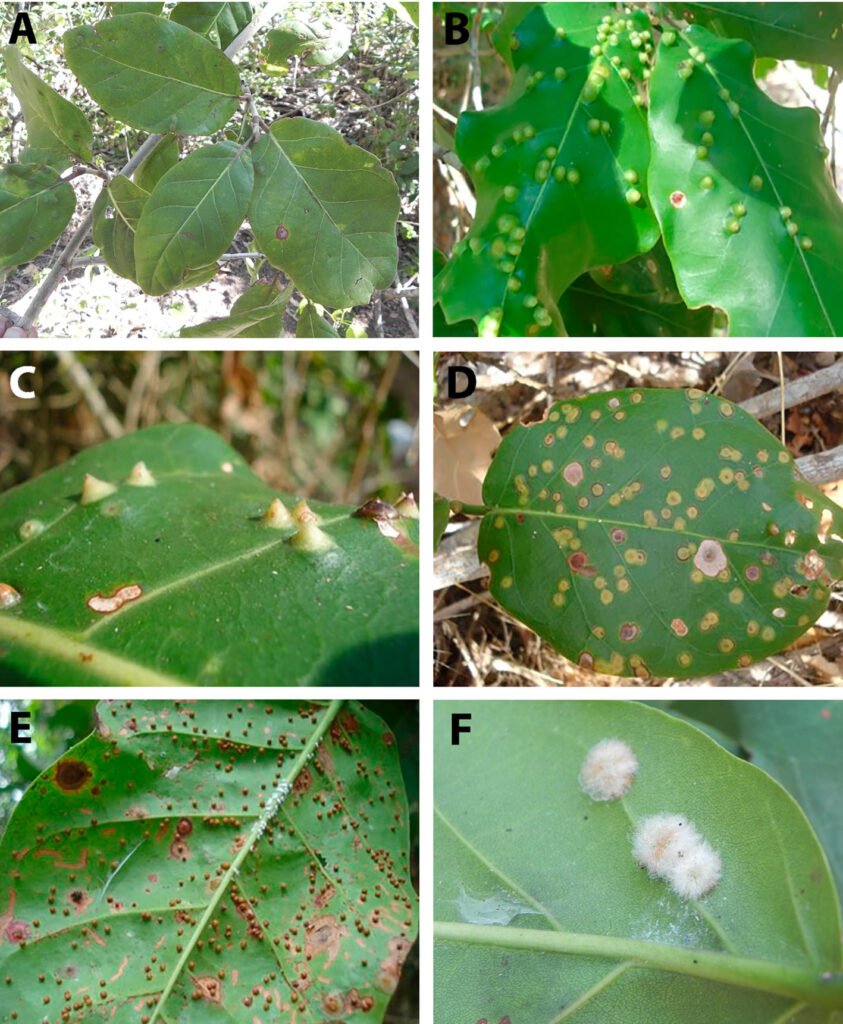

A total of 11,044 and 1,127 galls were dissected from 480 and 50 leaves obtained from the 15 trees that were sampled during the dry and rainy seasons, respectively. Five gall morphotypes from the leaves of C. barbadensis were identified (Fig. 1A-F): 1) capsule-shaped (Fig. 1B), green on both sides, glabrous, with a central inner elongated canal; 2) conical (Fig. 1C), pale green on both sides, ending on a sharp tip on the beam, glabrous, with an internal round chamber; 3) flattened (Fig. 1D), greenish-yellow on the beam and brown on the underside, glabrous, with a horizontal centrally elongated chamber; 4) spherical (Fig. 1E), glabrous, flat, indistinct and brown on the beam, brown and spherical on the underside, distributed irregularly along the leaf; and 5) rounded (Fig. 1F), brown on both sides, with abundant whitish pubescence. All gall morphotypes were recorded in both seasons except gall morphotype 5, which was not recorded during the rainy season.

Figure 1. Leaf gall morphotypes found on Coccoloba barbadensis Jacq. (Polygonaceae). A) Leaves of C. barbadensis; B) capsule-shaped gall; C) conical gall; D) flattened gall; E) spherical gall; F) rounded gall.

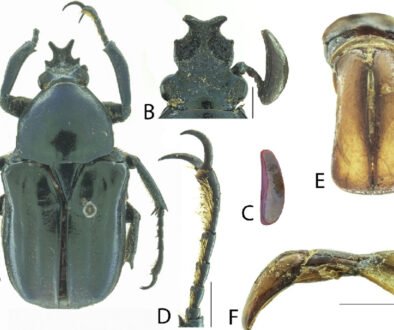

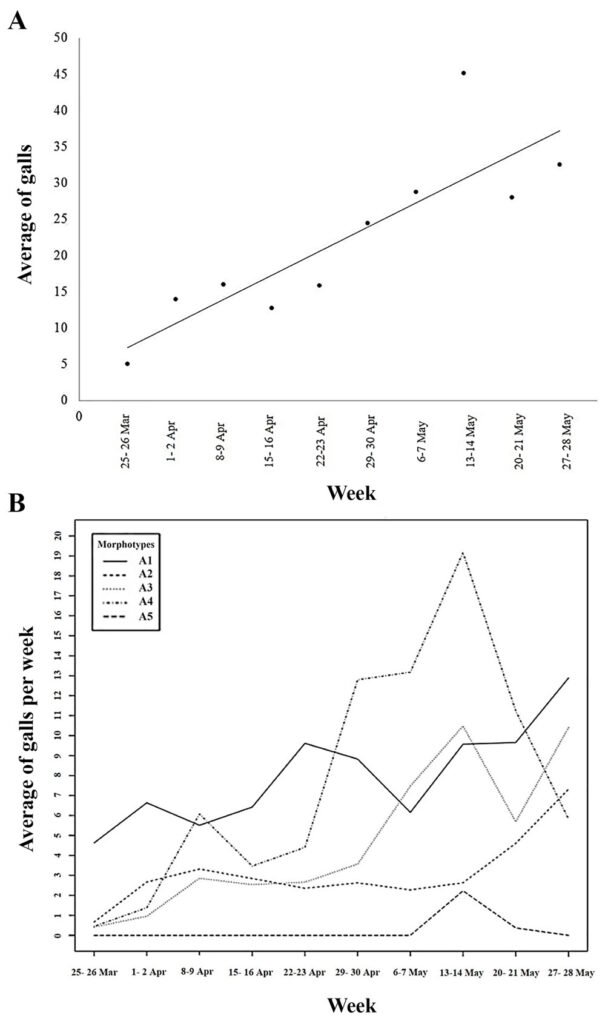

A significant relationship (R2 = 0.731, F = 21.796, p < 0.001) between the average number of total galls collected during the sampled weeks was observed, with the presence of galls in the leaves gradually increasing throughout the weeks during the dry season. The number of galls was relatively constant during the first 4 weeks (March 25-29 to April 22-23), but from the fifth week (April 29-30) it gradually increased (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2. A) Simple linear regression showing the average number of collected leaf galls on C. barbadensis during the time of collect in the dry season; B) graphic showing the average number of each leaf gall morphotype during the time of collect in the dry season.

Most galls collected during the dry season corresponded to gall morphotypes 1 and 4 (35% and 32%, respectively) and were present in 87% and 80% of the examined trees, respectively. Cecidomyiid exuviates adhered to the latter 2 gall morphotypes during the first 2 sampling weeks (25-26th of March – 1-2nd of April) and the last week of February, respectively. On the other hand, 13%, 18.5%, and 1.5% of the remaining galls belonged to gall morphotypes 2, 3, and 5 and occurred in 73%, 80%, and 13% of the trees, respectively. During the rainy season, 17.5%, 26.4%, 30.7%, and 25.4% of the collected galls corresponded to morphotype galls 1 to 4, respectively.

The average number of each gall morphotype varied over time during the dry season. There were significant differences between each type of gall (F3,128 = 8.616, p < 0.001) (Fig. 2B). The frequency of gall morphotype 1 gradually increased during the first weeks, though by the last week of April they were no longer registered. In contrast, gall morphotype 2 showed a lower abundance but its number was relatively constant throughout the sampling period, whereas gall morphotypes 3 and 4 had a low frequency but their number increased towards the first week of May. Gall morphotype 5 was only observed during the last 2 sampling weeks.

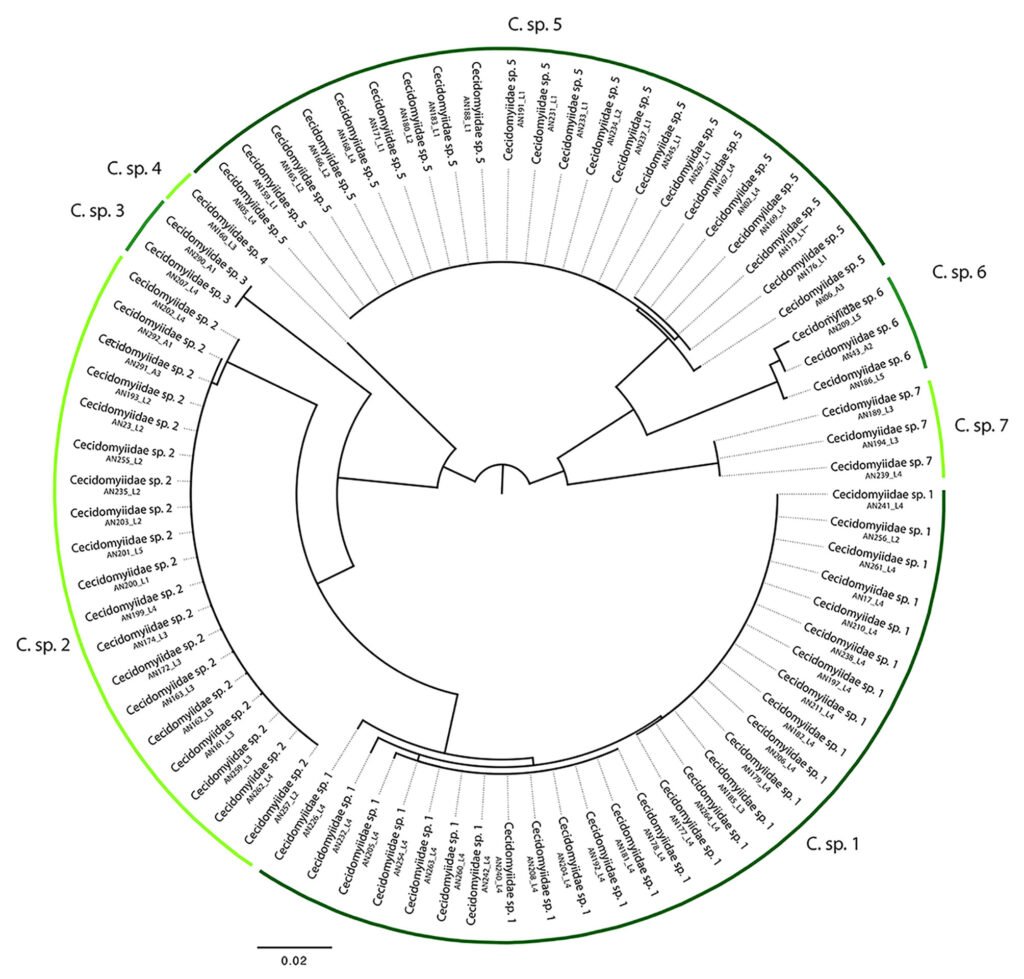

Integrative taxonomy

A total of 2,008 larvae and 356 adult insects were obtained from the dissected galls during both seasons. The morphospecies including larvae, pupae, and adults were first discriminated, for which were subsequently generated 230 COI sequences (151 sequences of Hymenoptera, 77 of Diptera, 1 of Coleoptera, and 1 of Lepidoptera (GenBank accession numbers in Appendix) resulting in 125 haplotypes. The number of species per family delimited by the 2 DNA sequence-based species delimitation approaches is provided in Table 1. The 2% COI divergence criterion and the GMYC model discriminated between 34 and 38 species, respectively. The NJ distance tree derived from the examined COI sequences of Hymenoptera and Diptera is shown in figures 3 and 4, respectively. There were 2 inconsistencies between both approaches. The 2% COI divergence criterion delimited 1 species of Chrysonotomyia (Entedoninae: Eulophidae) and 2 of Teniupetiolus (Eurytominae: Eurytomidae), whereas the GMYC model divided them into 3 and 2 species, respectively.

DNA sequence data supported most of the delimited species using larvae and adults, except for the only species of Torymus Dalman (Hymenoptera: Torymidae), the 3 species of Cecidomyiidae (Diptera), and the single species of Lepidoptera and Coleoptera, for which we only generated sequences of larvae.

Insect-gall association

Gall morphotype 3 had the highest insect species richness (20 species), which comprised all sampled families except the hymenopteran species of Braconidae (Allorhogas coccolobae Martínez & Zaldívar-Riverón) and Torymidae (Torymus sp.). This gall morphotype also had the highest number of eulophid species (8), from which 5 belong to the subfamily Tetrastichinae and was only present in this gall morphotype. Gall morphotype 1 had 18 associated insect species, with Platygastridae and Eurytomidae (Hymenoptera) being the families with more species (5 and 4 species, respectively; Table 2). Gall morphotypes 2 and 4, on the other hand, registered 9 and 12 species, respectively, whereas gall morphotype 5 only had 4 species, 1 belonging to Eulohpidae (Hymenoptera), 1 to Platygastridae (Hymenoptera) and 2 to Cecidomyiidae (Diptera) (Table 2).

Larvae of Cecidomyiidae were highly abundant throughout the dry season. The abundance of larvae and adults of the families Eurytomidae and Braconidae, on the other hand, considerably increased towards the sixth week of the dry season. In contrast, the presence of immature stages of Eulophidae was more frequent at the beginning of the dry season, though adults were also observed throughout this sampling period. Platygastridae was the hymenopteran family that was most frequently found in both larval and adult stages. Only immature individuals of Cecidomyiidae (Diptera) and Eulophidae (Hymenoptera) were collected during the rainy season.

A statistically significant difference (c2 = 912,989, df = 102, p <0.001) was observed between the 4 morphotypes of galls recorded during the dry season and their associated insect species. Fourteen out of the 37 insect species delimited with 2% barcoding were associated with a single gall morphotype. These included a species of Tenuipetiolus (Eurytomidae) in gall morphotype 1, 5 of Tetrastichinae (Eulophidae) in gall morphotypes 3, 1 species of Chrysonotomyia (Eulophidae) in gall morphotypes 1, 2 and 3, respectively, the single species of Eupelmidae and Torymidae in gall morphotypes 1 and 4, respectively, 2 and 1 species of Platygastridae in gall morphotypes 1 and 3, respectively, and 1 species of Cecidomyiidae in gall morphotype 3. Five delimited species of Cecidomyiidae were recorded in gall morphotypes 3 and 4, whereas 4, 3, and 2 were present in gall morphotypes 2, 1, and 5, respectively.

Discussion

A considerable leaf gall diversity in C. barbadensis is recorded here. Based on the gathered information, the inducers of these 5 types of leaf galls were species of Cecidomyiidae (Diptera) (see below). Other cecidomyiid galls that have been reported on species of Coccoloba include those found on stems of C. mosenii Lindl., on leaves of Coccoloba cf. warmingii Meisn., C. diversifolia Jacq., C. swartzii Kuntze, and C. uvifera Meins., and on inflorescences of C. alnifolia Casar (Mead, 1970; Maia et al., 2008; Ramos-Rodrigues et al., 2014). The number of different types of galls found in C. barbadensis (5 morphotypes) is higher than those reported for the above species (≤ 2 morphotypes). However, based on their general appearance, the gall morphotypes 1 and 2 may be variants made by the same inducer species. Further rearing observations and molecular characterisation of gall inducers will help to confirm the actual gall diversity that is present on the leaves of this plant species.

Figure 3. Neighbour Joining phenogram reconstructed for specimens of Cecidomyiidae that were reared from the 4 leaf gall morphotypes found in C. barbadensis. Bars refer to the 7 species of Cecidomyiidae that were delimited with the 2% barcoding approach.

There is considerable morphological diversity in the leaf gall morphotypes found on C. barbadensis (Fig. 1A-F).

All these gall morphotypes were located on the leaf blade, with 4 of them being located on the beam and 1 on the underside. The considerable morphological diversity of these leaf galls can be attributed to several factors, among which include the high synthetic activity, rapid growth, structural and functional features, and characteristic morphogenetic patterns of leaf development (Mani, 1964). Further studies on these leaf galls are therefore necessary for a better understanding of the structural and histological differences among the leaf galls found on C. barbadensis.

Insect species richness

The high morphological diversity found on leaf galls favours the existence of a complex insect community (Mani, 1964); however, few studies have assessed in detail the insect community associated with leaf galls of Neotropical plant species (e.g., Maia, 2012). In this research, the extensive insect rearing, and examination of both molecular and morphological information helped to thoroughly characterise the insect species diversity found in the 5 types of galls present on leaves of C. barbadensis. Despite that, was not possible to confirm at this stage the biology of the reared taxa, and then their probable role is based on the relevant literature and the field observations.

Cecidomyiids, commonly known as gall midges, represent by far the group of insects with the most gall-inducer species (Gagné & Jaschhof, 2021). Species of Cecidomyiidae are mainly gall-formers, though members of the tribe Cecidomyiini are known to have a wide range of biologies, including only simple and complex gall formers, free-living, mycophagous, inquiline phytophagous, predator species of mites, aphids, and coccids, as well as internal parasitoids of aphids and psyllids (Kim et al., 2014; Uechi et al., 2011). The field observations and the insect species diversity found in the 5 leaf gall morphotypes of C. barbadensis strongly suggest that they are induced by cecidomyiid species. Among this evidence was that most of the dissected galls had a single cecidomyiid larva. Moreover, several galls belonging to morphotype 2 had a cecidomyiid pupal exuviae hanging outside of a small opening, which is a common feature of many galls with former cecidomyiids. Since the 5 leaf gall morphotypes were formed by cecidomyiid species, the remaining species of this family delimited in the study probably are inquilines.

Figure 4. Neighbour Joining phenogram reconstructed for specimens of Hymenoptera that were reared from the 4 leaf gall morphotypes found in C. barbadensis. Bars refer to the 25 species of Hymenoptera that were delimited with the 2% barcoding approach.

The cecidomyiid larvae and their emerging adults could not be identified at the genus level; however, a BLAST similarity search of the barcoding locus for the delimited cecidomyiid species suggests that they are closely related to species of the Cecidomyiini genera Contarinia Geer and Macrodiplosis Kieffer. The gall-inducing species of the genus Contarinia are cosmopolitan and can be either monophagous or polyphagous with a wide range of hosts (Uechi et al., 2011). Most species of this genus live gregariously in the floral parts of the plant or in the galls that they induce on the leaves (Gagné & Jaschoff, 2021). Species of Macrodiplosis, on the other hand, are mainly gall inducers on leaves of plant species of the genus Quercus (Kim et al., 2014).

Table 1

Number of insect species discriminated by DNA sequence-based species delineation approaches conducted in this study (2% COI divergence criterion; GMYC method).

| Order/Family | Subfamily | Genus | 2% DC | GMYC |

| Diptera | ||||

| Cecidomyiidae | – | – | 7 | 7 |

| Lepidoptera | – | – | 1 | – |

| Coleoptera | – | – | 1 | – |

| Hymenoptera | ||||

| Braconidae | Doryctinae | Allorhogas coccolobae | 1 | 1 |

| Eulophidae | Entedoninae | Chrysonotomyia spp. | 6 | 8 |

| Tetrastichinae | Quadrastichus spp. | 5 | 5 | |

| Eupelmidae | Brasema sp. | 1 | 1 | |

| Eurytomidae | Eurytominae | Tenuipetiolus spp. | 5 | 7 |

| Platygastridae | Synopeas spp. | 3 | 3 | |

| Inostemma spp. | 1 | 1 | ||

| Undetermined | 2 | 2 | ||

| Torymidae | Torymus sp. | 1 | 1 | |

| Total | 34 | 38 |

Table 2

Insect species richness by order and family associated with 5 gall morphotypes found on leaves of Coocoloba barbadensis Jacq.

| Gall morphotypes (GM) | ||||||

| Insect Order/Family | GM 1 | GM 2 | GM 3 | GM 4 | GM 5 | TOTAL |

| Coleoptera | – | – | 1 | – | – | 1 |

| Lepidoptera | – | – | 1 | – | – | 1 |

| Diptera | ||||||

| Cecidomyiidae | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 19 |

| Hymenoptera | 15 | 5 | 13 | 7 | 2 | 42 |

| Eurytomidae | 4 | 2 | 3 | 3 | – | 12 |

| Eulophidae | 3 | 2 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 15 |

| Eupelmidae | 1 | – | – | – | – | 1 |

| Braconidae | 1 | – | – | 1 | – | 2 |

| Platygastridae | 5 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 11 |

| Torymidae | 1 | – | – | – | – | 1 |

| Total | 18 | 9 | 20 | 12 | 4 | 63 |

Currently, 4 gall midge species are known to be associated with species of Coccoloba. The genus Ctenodactylomyia Felt (supertribe Cecidomyiidi, unplaced tribe) has 2 leaf gall inducer species on C. diversifolia Jacq., C. swartzii, and C. uvifera L. from the Caribbean (Gagné & Jaschoff, 2021). Moreover, Marilasioptera tripartite Möhn and Meunieriella magdalenae Wünsch (supertribe Lasiopteridi, tribe Alycaulini) were described as inquilines on galls induced by other insects on species of Coccoloba from El Salvador and Colombia, respectively (Gagné & Jaschoff, 2021). The present study increases the number of gall midge species associated with Coccoloba to 11.

Our study also found a considerable number of hymenopteran species reared from the 5 examined leaf gall morphotypes, most of which probably are parasitoids of the cecidomyiid species. These parasitoid species belong to the wasp families Eulophidae, Eupelmidae, Platygastridae, and Torymidae, whereas the only reared braconid species probably are phytophagous inquiline. Some members of the Platygastridae are known to be koinobiont endoparasitoids of gallery cecidomyiid eggs, and they are known to be closely associated with the parts of the plant where the host gall is found (Masner & Huggert, 1989; Masner, 1993). Eulophidae are also mainly parasitoids of holometabolous insect larvae (though in some cases also of eggs, prepupae, and pupae) of Lepidoptera, Hymenoptera, Diptera, and Coleoptera (Graham, 1991); however, some species have been reported to be phytophagous or predators (Gibson, 1993). Finally, members of the eupelmid subfamily Eupelminae, from which the genus Brasema belongs, mainly are parasitoids of larval stages of various insect hosts (Gibson, 1993).

The wasp family Eurytomidae is represented by entomophagous species that parasitise larval or pupal stages of Coleoptera, Diptera, and Hymenoptera as solitary endoparasitic idiobionts, though some species can be phytophagous feeding on seeds, or inquilines feeding on both their host and gall tissue (Lotfalizadeh et al., 2007; Gates & Delvare, 2008). Species of Tenuipetiolus have been reported to be parasitoids of gall inducer insects, including cecidomyiids and cynipids (Gates & Hanson, 2006; Zhang et al., 2014). Similarly, several species of Torymidae are known to be ectoparasitoids of gall-forming insects of the latter 2 families (Gibson, 1993).

The braconid species A. coccolobae (Doryctinae) was described a decade ago from the Chamela region in Jalisco, Mexico, based on specimens reared from leaf galls of C. barbadensis (Martínez & Zaldívar-Riverón, 2013), that correspond to the morphotype 2. Here, this braconid species was reared not only from the above leaf gall morphotype but also from morphotype 4. Several species of Allorhogas have been confirmed to feed on various plant families either by being gall formers or inquilines of galls made by other insect taxa (Centrella & Shaw, 2010; Chavarría et al., 2009; de Mâcedo et al., 1998; Zaldívar-Riverón et al., 2014). Since none of the Allorhogas species with recorded biology are known to be parasitoids, and due to the low abundance of this species compared with the cecidomyiid species that were reared from the same gall morphotypes, it is presumed that it could be a phytophagous inquiline.

The considerably high, mostly undescribed species diversity of cecidomyiid dipterans and parasitoid hymenopterans that we reared from the 5 leaf gall morphotypes of C. barbadensis remark the necessity to carry out more studies that focus on the species diversity of galls, particularly in tropical regions. Moreover, this study highlights the importance of performing integrative species delineation studies of insects present in galls to have a more accurate knowledge of their actual diversity and trophic interactions.

Acknowledgments

We thank L. Márquez, N. López, and A. Jiménez for their assistance in the laboratory (Lanabio), and Cristina Mayorga for her assistance at the CNIN-IBUNAM. Angélica Rodríguez was supported by a MSc scholarship given by the Consejo Nacional de Humanidades, Ciencias y Tecnologías (Conahcyt, Mexico), and she thanks the Posgrado en Ciencias Biológicas, UNAM, for support during her MSc studies. This study was finished thanks to the grants given by UNAM-DGAPA (PAPIIT Convocatoria 2022, Project IN201622), and Conahcyt, Mexico (Convocatoria Ciencia de Frontera, project number 58548) to AZR.

| Appendix. Continued. | ||||

| Order (Insecta) | Family, Genus | Species | DNA voucher No. | Genbank accession No. |

| Diptera | Cecidomyiidae | sp. | CeciAN255_L2 | PP659768 |

| Diptera | Cecidomyiidae | sp. | CeciAN23_L2 | PP659794 |

| Diptera | Cecidomyiidae | sp. | CeciAN193_L2 | PP659795 |

| Diptera | Cecidomyiidae | sp. | CeciAN291_A3 | PP659802 |

| Diptera | Cecidomyiidae | sp. | CeciAN292_A1 | PP659803 |

| Diptera | Cecidomyiidae | sp. | CeciAN257_L2 | PP659804 |

| Diptera | Cecidomyiidae | sp. | CeciAN259_L3 | PP659805 |

| Diptera | Cecidomyiidae | sp. | CeciAN262_L4 | PP659806 |

| Diptera | Cecidomyiidae | sp. | CeciAN207_L4 | PP659797 |

| Diptera | Cecidomyiidae | sp. | CeciAN290_A1 | PP659801 |

| Diptera | Cecidomyiidae | sp. | CeciAN160_L3 | PP659807 |

| Diptera | Cecidomyiidae | sp. | CeciAN02_L4 | PP659731 |

| Diptera | Cecidomyiidae | sp. | CeciAN05_L4 | PP659732 |

| Diptera | Cecidomyiidae | sp. | CeciAN159_L1 | PP659733 |

| Diptera | Cecidomyiidae | sp. | CeciAN165_L2 | PP659734 |

| Diptera | Cecidomyiidae | sp. | CeciAN166_L2 | PP659735 |

| Diptera | Cecidomyiidae | sp. | CeciAN167_L3 | PP659736 |

| Diptera | Cecidomyiidae | sp. | CeciAN168_L4 | PP659737 |

| Diptera | Cecidomyiidae | sp. | CeciAN169_L4 | PP659738 |

| Diptera | Cecidomyiidae | sp. | CeciAN171_L1 | PP659739 |

| Diptera | Cecidomyiidae | sp. | CeciAN173_L1 | PP659740 |

| Diptera | Cecidomyiidae | sp. | CeciAN176_L1 | PP659741 |

| Diptera | Cecidomyiidae | sp. | CeciAN180_L2 | PP659742 |

| Diptera | Cecidomyiidae | sp. | CeciAN183_L1 | PP659743 |

| Diptera | Cecidomyiidae | sp. | CeciAN186_L5 | PP659744 |

| Diptera | Cecidomyiidae | sp. | CeciAN188_L1 | PP659745 |

| Diptera | Cecidomyiidae | sp. | CeciAN191_L1 | PP659747 |

| Diptera | Cecidomyiidae | sp. | CeciAN231_L1 | PP659750 |

| Diptera | Cecidomyiidae | sp. | CeciAN233_L1 | PP659751 |

| Diptera | Cecidomyiidae | sp. | CeciAN234_L2 | PP659752 |

| Diptera | Cecidomyiidae | sp. | CeciAN237_L1 | PP659753 |

| Diptera | Cecidomyiidae | sp. | CeciAN245_L1 | PP659755 |

| Diptera | Cecidomyiidae | sp. | CeciAN267_L1 | PP659756 |

| Diptera | Cecidomyiidae | sp. | CeciAN06_A3 | PP659791 |

| Diptera | Cecidomyiidae | sp. | CeciAN209_L5 | PP659749 |

| Diptera | Cecidomyiidae | sp. | CeciAN43_A2 | PP659792 |

| Diptera | Cecidomyiidae | sp. | CeciAN189_L3 | PP659746 |

| Diptera | Cecidomyiidae | sp. | CeciAN194_L3 | PP659748 |

| Diptera | Cecidomyiidae | sp. | CeciAN239_L4 | PP659754 |

| Hymenoptera | Platygaster | sp. | TeleAN08_L3 | PP481223 |

| Hymenoptera | Platygaster | sp. | TeleAN19_P3 | PP481224 |

| Hymenoptera | Platygaster | sp. | TeleAN46_A1 | PP481225 |

| Hymenoptera | Platygaster | sp. | TeleAN45_A3 | PP481226 |

| Hymenoptera | Platygaster | sp. | TeleAN50_A3 | PP481227 |

| Hymenoptera | Platygaster | sp. | TeleAN30_A3 | PP481228 |

| Hymenoptera | Platygaster | sp. | TeleAN132_A3 | PP481229 |

| Hymenoptera | Platygaster | sp. | TeleAN133_A1 | PP481230 |

| Hymenoptera | Platygaster | sp. | TeleAN134_A3 | PP481231 |

| Hymenoptera | Platygaster | sp. | TeleAN135_A1 | PP481232 |

| Hymenoptera | Platygaster | sp. | TeleAN137_A1 | PP481233 |

| Hymenoptera | Platygaster | sp. | TeleAN138_A3 | PP481234 |

| Hymenoptera | Platygaster | sp. | TeleAN141_A3 | PP481235 |

| Hymenoptera | Platygaster | sp. | TeleAN151_A3 | PP481236 |

| Hymenoptera | Platygaster | sp. | TeleAN152_A3 | PP481237 |

| Hymenoptera | Platygaster | sp. | TeleAN153_A3 | PP481238 |

| Hymenoptera | Platygaster | sp. | TeleAN154_A3 | PP481239 |

| Hymenoptera | Platygaster | sp. | TeleAN156_A3 | PP481240 |

| Hymenoptera | Platygaster | sp. | TeleAN215_L3 | PP481241 |

| Hymenoptera | Platygaster | sp. | TeleAN216_L3 | PP481242 |

| Hymenoptera | Platygaster | sp. | TeleAN217_L3 | PP481243 |

| Hymenoptera | Platygaster | sp. | TeleAN218_L3 | PP481244 |

| Hymenoptera | Platygaster | sp. | TeleAN224_L1 | PP481245 |

| Hymenoptera | Platygaster | sp. | TeleAN225_L1 | PP481246 |

| Hymenoptera | Platygaster | sp. | TeleAN275_L3 | PP481247 |

| Hymenoptera | Platygaster | sp. | TeleAN276_L3 | PP481248 |

| Hymenoptera | Platygaster | sp. | TeleAN281_A3 | PP481249 |

| Hymenoptera | Platygaster | sp. | TeleAN158_A1 | PP481250 |

| Hymenoptera | Platygaster | sp. | TeleAN110_A1 | PP481251 |

| Hymenoptera | Platygaster | sp. | TeleAN111_A3 | PP481252 |

| Hymenoptera | Synopeas | sp. | PlatyAN22_A1 | PP481253 |

| Hymenoptera | Synopeas | sp. | PlatyAN32_A1 | PP481254 |

| Hymenoptera | Synopeas | sp. | PlatyAN52_A1 | PP481255 |

| Hymenoptera | Synopeas | sp. | PlatyAN14_A1 | PP481256 |

| Hymenoptera | Synopeas | sp. | PlatyAN157_A1 | PP481257 |

| Hymenoptera | Synopeas | sp. | PlatyAN53_A1 | PP481258 |

| Hymenoptera | Synopeas | sp. | PlatyAN99_A1 | PP481259 |

| Hymenoptera | Synopeas | sp. | PlatyAN101_A1 | PP481260 |

| Hymenoptera | Synopeas | sp. | PlatyAN102_A1 | PP481261 |

| Hymenoptera | Synopeas | sp. | PlatyAN103_A1 | PP481262 |

| Hymenoptera | Synopeas | sp. | PlatyAN105_A1 | PP481263 |

| Hymenoptera | Synopeas | sp. | PlatyAN190_L2 | PP481264 |

| Hymenoptera | Synopeas | sp. | PlatyAN219_L1 | PP481265 |

| Hymenoptera | Inostemma | sp. | PlatyAN221_L4 | PP481266 |

| Hymenoptera | Synopeas | sp. | PlatyAN223_L2 | PP481267 |

| Hymenoptera | Synopeas | sp. | PlatyAN220_L5 | PP481268 |

| Hymenoptera | Inostemma | sp. | PlatyAN112_A4 | PP481269 |

| Hymenoptera | Synopeas | sp. | PlatyAN116_A1 | PP481270 |

| Hymenoptera | Synopeas | sp. | PlatyAN117_A1 | PP481271 |

| Hymenoptera | Synopeas | sp. | PlatyAN118_A1 | PP481272 |

| Hymenoptera | Inostemma | sp. | PlatyAN126_A1 | PP481273 |

| Hymenoptera | Synopeas | sp. | PlatyAN214_L1 | PP481274 |

| Hymenoptera | Platygaster | sp. | PlatyAN222_L3 | PP481275 |

| Hymenoptera | Synopeas | sp. | PlatyAN272_A1 | PP481276 |

| Hymenoptera | Synopeas | sp. | PlatyAN273_L | PP481277 |

| Hymenoptera | Synopeas | sp. | PlatyAN274_L | PP481278 |

| Hymenoptera | Synopeas | sp. | PlatyAN277_L5 | PP481279 |

| Hymenoptera | Synopeas | sp. | PlatyAN278_L2 | PP481280 |

| Hymenoptera | Synopeas | sp. | PlatyAN279_L1 | PP481281 |

| Hymenoptera | Tenuipetiolus | sp. | EurytAN96_A1 | PP481282 |

| Hymenoptera | Tenuipetiolus | sp. | EurytAN265_L3 | PP481283 |

| Hymenoptera | Chrysonotomyia | sp. | EntedAN01_P1 | PP481284 |

| Hymenoptera | Chrysonotomyia | sp. | EntedAN07_A1 | PP481285 |

| Hymenoptera | Chrysonotomyia | sp. | EntedAN29_A1 | PP481286 |

| Hymenoptera | Chrysonotomyia | sp. | EntedAN11_A1 | PP481287 |

| Hymenoptera | Chrysonotomyia | sp. | EntedAN31_A1 | PP481288 |

| Hymenoptera | Chrysonotomyia | sp. | EntedAN51_A1 | PP481289 |

| Hymenoptera | Chrysonotomyia | sp. | EntedAN59_P1 | PP481290 |

| Hymenoptera | Chrysonotomyia | sp. | EntedAN61_P1 | PP481291 |

| Hymenoptera | Chrysonotomyia | sp. | EntedAN67_P1 | PP481292 |

| Hymenoptera | Chrysonotomyia | sp. | EntedAN69_A1 | PP481293 |

| Hymenoptera | Chrysonotomyia | sp. | EntedAN70_A1 | PP481294 |

| Hymenoptera | Chrysonotomyia | sp. | EntedAN71_A1 | PP481295 |

| Hymenoptera | Chrysonotomyia | sp. | EntedAN72_A1 | PP481296 |

| Hymenoptera | Chrysonotomyia | sp. | EntedAN75_A1 | PP481297 |

| Hymenoptera | Chrysonotomyia | sp. | EntedAN94_A1 | PP481298 |

| Hymenoptera | Chrysonotomyia | sp. | EntedAN95_A1 | PP481299 |

| Hymenoptera | Chrysonotomyia | sp. | EntedAN25_A2 | PP481300 |

| Hymenoptera | Chrysonotomyia | sp. | EntedAN64_P4 | PP481301 |

| Hymenoptera | Chrysonotomyia | sp. | EntedAN73_A3 | PP481302 |

| Hymenoptera | Chrysonotomyia | sp. | EntedAN142_A1 | PP481303 |

| Hymenoptera | Chrysonotomyia | sp. | EntedAN143_A1 | PP481304 |

| Hymenoptera | Chrysonotomyia | sp. | EntedAN144_A1 | PP481305 |

| Hymenoptera | Chrysonotomyia | sp. | EntedAN145_A1 | PP481306 |

| Hymenoptera | Chrysonotomyia | sp. | EntedAN146_A2 | PP481307 |

| Hymenoptera | Chrysonotomyia | sp. | EntedAN198_L3 | PP481308 |

| Hymenoptera | Chrysonotomyia | sp. | EntedAN236_L1 | PP481309 |

| Hymenoptera | Chrysonotomyia | sp. | EntedAN243_L1 | PP481310 |

| Hymenoptera | Chrysonotomyia | sp. | EntedAN244_L1 | PP481311 |

| Hymenoptera | Chrysonotomyia | sp. | EntedAN288_A2 | PP481312 |

| Hymenoptera | Chrysonotomyia | sp. | EntedAN289_A2 | PP481313 |

| Hymenoptera | Chrysonotomyia | sp. | EntedAN58_P1 | PP481314 |

| Hymenoptera | Chrysonotomyia | sp. | EntedAN55_A1 | PP481315 |

| Hymenoptera | Chrysonotomyia | sp. | EulopAN125_A5 | PP481316 |

| Hymenoptera | Tetrastichinae | sp. | TetrasAN84_A3 | PP481317 |

| Hymenoptera | Tetrastichinae | sp. | TetrasAN62_P3 | PP481318 |

| Hymenoptera | Tetrastichinae | sp. | TetrasAN63_P3 | PP481319 |

| Hymenoptera | Tetrastichinae | sp. | TetrasAN66_P3 | PP481320 |

| Hymenoptera | Tetrastichinae | sp. | TetrasAN83_A3 | PP481321 |

| Hymenoptera | Tetrastichinae | sp. | TetrasAN60_P3 | PP481322 |

| Hymenoptera | Tetrastichinae | sp. | TetrasAN269_L3 | PP481323 |

| Hymenoptera | Tetrastichinae | sp. | TetrasAN270_L3 | PP481324 |

| Hymenoptera | Tenuipetiolus | sp. | EurytAN77_A1 | PP481325 |

| Hymenoptera | Tenuipetiolus | sp. | EurytAN81_A3 | PP481326 |

| Hymenoptera | Tenuipetiolus | sp. | EurytAN93_A3 | PP481327 |

| Hymenoptera | Allorhogas | coccolobae | AllorAN18_L4 | PP481328 |

| Hymenoptera | Allorhogas | coccolobae | AllorAN28_A4 | PP481329 |

| Hymenoptera | Allorhogas | coccolobae | AllorAN35_A4 | PP481330 |

| Hymenoptera | Allorhogas | coccolobae | AllorAN48_A4 | PP481331 |

| Hymenoptera | Allorhogas | coccolobae | AllorAN56_A4 | PP481332 |

| Hymenoptera | Allorhogas | coccolobae | AllorAN107_A4 | PP481333 |

| Hymenoptera | Allorhogas | coccolobae | AllorAN108_A4 | PP481334 |

| Hymenoptera | Allorhogas | coccolobae | AllorAN109_A4 | PP481335 |

| Hymenoptera | Allorhogas | coccolobae | AllorAN121_A4 | PP481336 |

| Hymenoptera | Allorhogas | coccolobae | AllorAN122_A4 | PP481337 |

| Hymenoptera | Allorhogas | coccolobae | AllorAN195_L1 | PP481338 |

| Hymenoptera | Allorhogas | coccolobae | AllorAN248_L4 | PP481339 |

| Hymenoptera | Allorhogas | coccolobae | AllorAN249_L4 | PP481340 |

| Hymenoptera | Tenuipetiolus | sp. | EurytAN212_L3 | PP481341 |

| Hymenoptera | Tenuipetiolus | sp. | EurytAN228_L3 | PP481342 |

| Hymenoptera | Tenuipetiolus | sp. | EurytAN246_L3 | PP481343 |

| Hymenoptera | Tenuipetiolus | sp. | EurytAN285_A3 | PP481344 |

| Hymenoptera | Tenuipetiolus | sp. | EurytAN286_A3 | PP481345 |

| Hymenoptera | Tenuipetiolus | sp. | EurytAN37_A1 | PP481346 |

| Hymenoptera | Tenuipetiolus | sp. | EurytAN147_A3 | PP481347 |

| Hymenoptera | Tenuipetiolus | sp. | EurytAN148_A4 | PP481348 |

| Hymenoptera | Tenuipetiolus | sp. | EurytAN149_A3 | PP481349 |

| Hymenoptera | Tenuipetiolus | sp. | EurytAN130_A1 | PP481350 |

| Hymenoptera | Tenuipetiolus | sp. | EurytAN87_A2 | PP481351 |

| Hymenoptera | Tenuipetiolus | sp. | EurytAN91_A4 | PP481352 |

| Hymenoptera | Tenuipetiolus | sp. | EurytAN80_A3 | PP481353 |

| Hymenoptera | Tenuipetiolus | sp. | EurytAN82_A4 | PP481354 |

| Hymenoptera | Tenuipetiolus | sp. | EurytAN90_A4 | PP481355 |

| Hymenoptera | Tenuipetiolus | sp. | EurytAN85_A1 | PP481356 |

| Hymenoptera | Torymus | sp. | EurytAN57_A4 | PP481357 |

| Hymenoptera | Tenuipetiolus | sp. | EurytAN164_L1 | PP481358 |

| Hymenoptera | Tenuipetiolus | sp. | EurytAN227_L1 | PP481359 |

| Hymenoptera | Tenuipetiolus | sp. | EurytAN230_L1 | PP481360 |

| Hymenoptera | Tenuipetiolus | sp. | EurytAN283_A2 | PP481361 |

| Hymenoptera | Tenuipetiolus | sp. | EurytAN33_A4 | PP481362 |

| Hymenoptera | Tenuipetiolus | sp. | EurytAN34_A1 | PP481363 |

| Hymenoptera | Tenuipetiolus | sp. | EurytAN15_L1 | PP481364 |

| Hymenoptera | Tenuipetiolus | sp. | EurytAN114_A3 | PP481365 |

| Hymenoptera | Tenuipetiolus | sp. | EurytAN79_A1 | PP481366 |

| Hymenoptera | Tenuipetiolus | sp. | EurytAN78_A1 | PP481367 |

| Hymenoptera | Tenuipetiolus | sp. | EurytAN24_L1 | PP481368 |

| Hymenoptera | Chrysonotomyia | sp. | EurytAN88_A3 | PP481369 |

| Hymenoptera | Brasema | sp. | ToryAN170_L1 | PP481370 |

| Hymenoptera | Brasema | sp. | ToryAN196_L1 | PP481371 |

| Hymenoptera | Torymus | sp. | EurytAN229_L4 | PP481372 |

| Hymenoptera | Torymus | sp. | EurytAN266_L4 | PP481373 |

| Coleoptera | AN184 | PP897664 | ||

| Lepidoptera | AN250_L3 | PP897665 |

References

Altschul, S. F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E. W., & Lipman, D. J. (1990). Basic local alignment search tool. Journal of Molecular Biology, 215, 403–410. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2

Bortolus, A. (2008). Error cascades in the biological sciences: the unwanted consequences of using bad taxonomy in ecology. AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment, 37, 114–118. https://doi.org/10.1579/0044-7447(2008)37[114:ECITBS]2.0.CO;2

Bouckaert, R., Heled, J., Kühnert, D., Vaughan, T., Wu, C. H., Xie, D., Suchard, M. A., Rambaut, A., & Drummond, A. J. (2014). BEAST 2: A software platform for Bayesian evolutionary analysis. Plos Computational Biology, 10, e1003537. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003537

Centrella, M. L., & Shaw, S. R. (2010). A new species of phytophagous braconid Allorhogas minimus (Hymenoptera: Braconidae: Doryctinae) reared from fruit galls on Miconia longifolia (Melastomataceae) in Costa Rica. International Journal of Tropical Insect Science, 30, 101–107. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742758410000147

Chavarría, L., Hanson, P., Marsh, P., & Shaw, S. (2009). A phytophagous braconid, Allorhogas conostegia sp. nov.(Hymenoptera: Braconidae), in the fruits of Conostegia xalapensis (Bonpl.) D. Don (Melastomataceae). Journal of Natural History, 43, 2677–2689. https://doi.org/10.1080/

00222930903243996

Clare, E. L., Schiestl, F. P., Leitch, A. R., & Chittka, L. (2013). The promise of genomics in the study of plant-pollinator interactions. Genome Biology, 14, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.

1186/gb-2013-14-6-207

de Macêdo, M. V., & Monteiro, R. F. (1989). Seed predation by a braconid wasp, Allorhogas sp. (Hymenoptera). Journal of the New York Entomological Society, 97, 358–362.

Dexter, K. G., Pennington, T. D., & Cunningham, C. W. (2010). Using DNA to assess errors in tropical tree identifications: How often are ecologists wrong and when does it matter? Ecological Monographs, 80, 267–286. https://doi.org/10.1890/09-0267.1

Drummond, A. J., Suchard, M. A., Xie, D., & Rambaut, A. (2012). Bayesian phylogenetics with BEAUti and the BEAST 1.7. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 29, 1969–1973. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/mss075

Folmer O., Black, M., Hoeh, W., Lutz, R., & Vrijenhoek, R. (1994). DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Molecular Marine Biology and Biotechnology, 3, 294–299.

Forbes, A. A., Hall, M. C., Lund, J., Hood, G. R., Izen, R., Egan, S. P. et al. (2016). Parasitoids, hyperparasitoids, and inquilines associated with the sexual and asexual generations of the gall former, Belonocnema treatae (Hymenoptera: Cynipidae). Annals of the Entomological Society of America, 109, 49–63. https://doi.org/10.1093/aesa/sav112

Gagné, R. J., & Jaschhof, M. (2021). A catalog of the

Cecidomyiidae (Diptera) of the World, 5th Edition. Available

at: https://www.ars.usda.gov/ARSUserFiles/80420580/Gag

ne_Jaschhof_2021_World_Cat_5th_Ed.pdf

Gates, M. W., & Hanson, P. E. (2006). Familia Eurytomidae, In P. E. Hanson, & I. D. Gauld (Eds.), Hymenoptera de la region tropical (pp. 380–387). Memoirs of the American Entomological Institute, 77, 1–994.

Gates, M., & Delvare, G. (2008). A new species of Eurytoma (Hymenoptera: Eurytomidae) attacking Quadrastichus spp. (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae) galling Erythrina spp. (Fabaceae), with a summary of African Eurytoma biology and species checklist. Zootaxa, 1751, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.1751.1.1

Gibson, L. (1993). Superfamilies Mymarommatoidea and Chalcidoidea. In H. Goulet, & J. T. Huber (Eds.), Hymenoptera of the world: an identification guide to families (pp.570–655). Research Branch, Agriculture, Canada, Publication 1894.

Graham, M. W. R. V. (1991). A reclassification of the European Tetrastichinae (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae). Revision of the remaining genera. Memoirs of the American Entomological Institute, 49, 1–322.

Hebert, P. D., Cywinska, A., Ball, S. L., & DeWaard, J R. (2003). Biological identifications through DNA barcodes. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 2070, 313–321. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2002.2218

Hebert, P. D., Penton, E. H., Burns, J. M., Janzen, H. D., & Hallwachs, W. (2004). Ten species in one: DNA barcoding reveals cryptic species in the Neotropical skipper butterfly Astrapes fulgerator. Proceeding of the National Academy of Sciences, 101, 14812–14817. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.

0406166101

Howard, R. A. (1959). Studies in the genus Coccoloba. VII A synopsis and key to species in Mexico and Central America. Journal of the Arnold Arboretum, 40, 176–203.

Ings, T. C., Montoya, J. M., Bascompte, J., Blüthgen, N., Brown, L., Dormann, C. F. et al. (2009). Ecological networks-beyond food webs. Journal of Animal Ecology, 78, 253–269. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2656.2008.01460.x

Kaartinen, R., Stone, G. N., Hearn, J., Lohse, K., & Roslin, T. (2010). Revealing secret liaisons: DNA barcoding changes our understanding of food webs. Ecological Entomology, 35, 623–638. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2311.2010.01224.x

Kaartinen, R., & Roslin, T. (2011). Shrinking by numbers: landscape context affects the species composition but not the quantitative structure of local food webs. Journal of Animal Ecology, 80, 622–631. https://doi.org/10.1111/

j.1365-2656.2011.01811.x

Kim, W., Yukawa, J., Harris, K. M., Minami, T., Matsuo, K., & Skrzypczyńska, M. (2014). Description, host range, and distribution of a new Macrodiplosis species (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae) that induces leaf-margin fold galls on deciduous Quercus (Fagaceae) with comparative notes on Palaearctic congeners. Zootaxa, 3821, 222–238. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3821.2.3

Lotfalizadeh, H., Delvare, G., & Rasplus, J. Y. (2007). Phylogenetic analysis of Eurytominae (Chalcidoidea: Eurytomidae) based on morphological characters. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 151, 441–510. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.2007.00308.x

Maia, V. C., Magenta, M. A. G., & Martins, S. E. (2008). Ocorrência e caracterização de galhas de insetos em áreas de restinga de Bertioga (São Paulo, Brasil). Biota Neotropica, 8, 167–197. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1676-06032

008000100020

Maia, V. C. (2012). Richness of hymenopterous galls from South America. Papéis Avulsos de Zoologia, 52, 423–429. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0031-10492012021500001

Mani, M. S. (1964). Ecology of plant galls. The Hague: W. Junk.

Martínez, J. J., & Zaldívar-Riverón, A. (2013). Seven new species of Allorhogas (Hymenoptera: Braconidae: Doryctinae) from Mexico. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 84, 117–139. https://doi.org/10.7550/rmb.31955

Masner, L., & Huggert, L. (1989). World review and keys to genera of the subfamily Inostemmatinae with the reassignment of the taxa to the Platygastrinae and Sceliotrachelinae (Hymenoptera: Platygastridae). The Memoirs of the Entomological Society of Canada, 121, 3–216.

Masner, L. (1993). Superfamily Platygastroidea. In H. Goulet, & J. T. Huber (Eds.), Hymenoptera of the world: an identification guide to families (pp.558–565). Research Branch, Agriculture, Canada, Publication 1894.

Mead, F. W. (1970). Ctenodactylomyia watsoni Felt, a gall midge of seagrape, Coccoloba uvifera L. Florida (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae). Entomology Circular, 97. Florida Department of Agriculture & Consumer Services Division of Plant Industry. Florida, USA.

Méndez-Alonzo, R., Pineda-García, F., Paz, H., Rosell, J. A., & Olson, M. E. (2013). Leaf phenology is associated with soil water availability and xylem traits in a tropical dry forest. Trees, 27, 745–754. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00468-012-0829-x

Nieves-Aldrey, J. L. (1998). Insectos que inducen la formación de agallas en las plantas: Una fascinante interacción ecológica y evolutiva. Boletín de la Sociedad Entomológica Aragonesa, 23, 3–12.

Noguera, F. A., Vega-Rivera, J. H., García-Aldrete, A. N., Quesada-Avendaño, M. (Eds.). (2002). Historia natural de Chamela. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Paine, R. T. (1980). Food webs: linkage, interaction strength, and community infrastructure. Journal of Animal Ecology, 49, 667–685. https://doi.org/10.2307/4220

Pons, J., Barraclough, T. G., Gomez-Zurita, J., Cardoso, A., Duran, D. P., Hazell, S., Kamoun, S., Sumlin, W. D., & Vogler, A. P. (2006). Sequence-based species delimitation for the DNA taxonomy of undescribed insects. Systematic Biology, 55, 595-609. https://doi.org/10.1080/10635150600852011

Posada, D. (2004). Collapse: describing haplotypes from sequence alignments. Vigo, Spain: University of Vigo. https://dposada.webs.uvigo.es/

Price, P. W. (2005). Adaptive radiation of gall-inducing insects. Basic and Applied Ecology, 6, 413–421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.baae.2005.07.002

Prosser, S., Martínez-Arce, A., & Elías-Gutiérrez, M. (2013). A new set of primers for COI amplification from freshwater microcrustaceans. Molecular Ecology Resources, 13, 1151–1155. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.12132

R Core Team (2021). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for statistical computing, Vienna, Austria. http://r-forge.r-project.org/projects/splits/

Raman, A., & Withers, T. M. (2003). Oviposition by introduced Ophelimus eucalypti (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae) and morphogenesis of female-induced galls on Eucalyptus saligna (Myrtaceae) in New Zealand. Bulletin of Entomological Research, 93, 55–63. https://doi.org/10.1079/BER2002217

Raman, A. (2011). Morphogenesis of insect-induced plant galls facts and questions. Flora-Morphology, Distribution, Functional Ecology of Plants, 206, 517–533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.flora.2010.08.004

Ratnasingham, S., & Hebert, P. D. N. (2013). A DNA-based registry for all animal species: the barcode index number (BIN) system. Plos One, 8, e66213. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0066213

Razo-González, M., Castano-Meneses, G., Callejas-Chavero, A., Pérez-Velázquez, D., & Palacios-Vargas, J. G. (2014). Temporal variations of soil arthropods community structure in El Pedregal de San Ángel ecological reserve, Mexico City, Mexico. Applied Soil Ecology, 83, 88–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2014.02.007

Redfern, M., Shirley, P., & Bloxham, M. (2002). British plant galls: identification of galls on plants and fungi. Shrewsbury, UK: FSC publications.

Rodrigues, A. R., Maia, V. C., & Couri, M. S. (2014). Insect galls of restinga areas of Ilha da Marambaia, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Entomologia, 58, 173–197. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0085-56262014000200010

Sheffield, C. S., Hebert, P. D. N., Kevan, P. G., & Packer, L. (2009). DNA barcoding a regional bee (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) fauna and its potential for ecological studies. Molecular Ecology Resources, 9, 196–207. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-0998.2009.02645.x

Statsoft, Inc. (2011). STATISTICA (Data Analysis Software System, version 10. http://www.statsoft.com

Swofford, D. L. (2003). PAUP*. Phylogenetic Analysis using parsimony (*and other methods). Version 4.0. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, Massachusetts.

Uechi, N., Yukawa, J., Tokuda, M., Ganaha-Kikumura, T., & Taniguchi, M. (2011). New information on host plants and distribution ranges of an invasive gall midge, Contarinia maculipennis (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae), and its congeners in Japan. Applied Entomology and Zoology, 46, 383–389. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13355-011-0050-1

Vink, C. J., Paquin, P., & Cruickshank, R. H. (2012). Taxonomy and irreproducible biological science. Bioscience, 62, 451–452. https://doi.org/10.1525/bio.2012.62.5.3

Wirta, H. K., Hebert, P. D., Kaartinen, R., Prosser, S. W., Várkonyi, G., & Roslin, T. (2014). Complementary molecular information changes our perception of food web structure. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111, 1885–1890. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1316990111

Yeo, D., Puniamoorthy, J., Ngiam, R. W. J., & Meier, R. (2018). Towards holomorphology in entomology: rapid and cost-effective adult–larva matching using NGS barcodes. Systematic Entomology, 43, 678–691. https://doi.org/10.1111/syen.12296

Zaldívar-Riverón, A., Martínez, J. J., Belokobylskij, S. A., Pedraza-Lara, C., shaw, S. R., Hanson, P. E., & Varela-Hernández, F. (2014). Systematics and evolution of gall formation in the plant-associated genera of the wasp subfamily Doryctinae (Hymenoptera: Braconidae). Systematic Entomology, 39, 633–659. https://doi.org/10.1111/syen.12078

Zhang, M. Y., Gates, M. W., & Shorthouse, J. D. (2014). Testing species limits of Eurytomidae (Hymenoptera) associated with galls induced by Diplolepis (Hymenoptera: Cynipidae) in Canada using an integrative approach. The Canadian Entomologist, 146, 321–334. https://doi.org/10.4039/tce.

2013.70