Taxonomía y Sistemática

Ecología

Genetic diversity and phenotypic variation in a parasitoid wasp involved in the yucca – yucca moth interaction

C. Rocío Álamo-Herrera a, María Clara Arteaga a, *, Rafael Bello-Bedoy b

a Centro de Investigación Científica y de Educación Superior de Ensenada, Departamento de Biología de la Conservación, Carretera Tijuana-Ensenada # 3918, Zona Playitas, 22860 Ensenada, Baja California, Mexico

b Universidad Autónoma de Baja California, Facultad de Ciencias, Carretera Transpeninsular # 3917, Colonia Playitas, 22860 Ensenada, Baja California, Mexico

*Corresponding author: arteaga@cicese.mx (M.C. Arteaga)

Received: 28 February 2024; accepted: 01 July 2024

Abstract

Tri-trophic interactions between plants, herbivores, and parasitoids are a valuable model for studying how they influence the distribution of genetic diversity and phenotypic variability of the species involved. This study examines the taxonomic, morphological, and genetic diversity of parasitoid wasps involved in the Yucca–Tegeticula interaction on the Baja California Peninsula. We surveyed 35 locations across the peninsula and collected 119 parasitoid wasps. Of these, 114 were adults, while the remaining 5 were in the pupal stage. Our study identified 2 genera of wasps: Bassus sp. (Ichneumonidae; n = 8) and Digonogastra sp. (Brachonidae; n = 111). Moreover, we found moderate levels of genetic diversity within the Digonogastra population across the peninsula. Additionally, this population constitutes a single panmictic group with indications of historical demographic expansion. Phenotypically, we identified sexual dimorphism and variation associated with its different hosts and environmental heterogeneity Digonogastra’s geographical range.

Keywords: Baja California Peninsula; Genetic structure; Host-association; Morphometrics; Tri-trophic interactions

© 2024 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Biología. Este es un artículo Open Access bajo la licencia CC BY-NC-ND

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Diversidad genética y variación fenotípica en una avispa parasitoide involucrada en la interacción entre yucas y sus polillas polinizadoras

Resumen

Las interacciones tritróficas entre plantas, herbívoros y parasitoides son un modelo valioso para estudiar cómo influyen en la distribución de la diversidad genética y la variabilidad fenotípica de las especies involucradas. Este estudio examinó la diversidad taxonómica, morfológica y genética de avispas parasitoides en la interacción Yucca-Tegeticula en la Península de Baja California. El estudio se realizó en 35 localidades recolectando 119 avispas parasitoides; 114 adultos y 5 pupas. Se identificaron 2 géneros de avispas: Bassus sp. (Ichneumonidae; n = 8) y Digonogastra sp. (Brachonidae; n = 111). Se encontraron niveles moderados de diversidad genética dentro de la población de Digonogastra en toda la península, constituyendo un único grupo panmítico con indicios de expansión demográfica histórica. Fenotípicamente, identificamos dimorfismo sexual y variación asociada con sus diferentes hospederos y la heterogeneidad ambiental a lo largo de la distribución geográfica de Digonogastra.

Palabras clave: Península de Baja California; Estructura genética; Asociación al hospedero; Morfometría; Interacción tri-trófica

Introduction

Tritrophic interactions between plants, herbivores, and parasitoids have become pivotal to understanding species diversity (Abdala-Roberts et al., 2019; Godfray, 1994; Singer & Stireman, 2005). Parasitoids maintain an antagonistic relationship with insect herbivores by depositing their eggs inside or on them, ultimately leading to the death of their host (Godfray, 1994; Quicke, 2015; Resh & Cardé, 2009). These parasitoids serve as an indirect defense for plants, controlling herbivore population levels (Abdala-Roberts et al., 2019; Cuautle & Rico-Gray, 2003; Heil, 2008). Plants attract parasitoids by emitting chemical signals that indicate the presence of herbivores, which enables parasitoids to locate their prey, thus establishing mutually beneficial interactions (Heil, 2008; Kappers et al., 2011; Takabayashi & Dicke, 1996).

Multiple studies have explored how interactions among organisms affect the genetic and phenotypic variation within species (e.g., Agrawal, 2001; Carmona et al., 2015). For instance, biotic interactions may differ geographically, resulting in local selection processes and differentiation of parasitoid populations (Althoff & Thompson, 2001; Kankare et al., 2005; Stireman et al., 2005). Environmental factors or geographical distances can also determine the distribution of these variations (Althoff, 2008; Lozier et al., 2009; Stireman et al., 2005). For example, the genetic population structure of the wasp Cotesia congregata Say, 1836 (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) is related to the different plant-hosts with which it interacts (Karns, 2009). Conversely, genetic diversity in the parasitoid wasp Eusandalum sp. Ratzeburg, 1852 (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) is primarily associated with its broad geographical distribution rather than the species it interacts with (Althoff, 2008).

The interaction between Yucca Linnaeus plants, moths of the family Prodoxidae and associated parasitoids have been recorded (Althoff, 2008; Pellmyr, 2003). In this tritrophic interaction, the female moth visits Yucca flowers and lays her eggs in the ovary. Subsequently, she pollinates the stigma by depositing pollen, ensuring the formation of fruits that the moth larvae will feed on (Engelmann, 1872). During fruit production, female parasitoid wasps use their ovipositors to lay eggs on moth larvae inside fruits, paralyzing the larvae (Force & Thompson, 1984). The wasp larva feeds on the host, completes its development, and emerges from the fruit as an adult (Althoff, 2008; Crabb & Pellmyr, 2006). The interaction between Yuccas and moths have driven differentiation and diversification processes in the involved species (Althoff et al., 2012; Althoff & Segraves, 2022; Pellmyr & Leebens-Mack, 1999). However, little is known about the third trophic level of this relationship, which consists of parasitoid wasps that interact with the moth (their food source) and the plant (their shelter until hatching).

In the Baja California Peninsula, 3 Yucca species and 2 Tegeticula Zeller, 1873 species are distributed allopatrically. Yucca schidigera Roezl ex Ortgies (Asparagales: Asparagaceae) occurs in the northern part of the peninsula and is pollinated by Tegeticula mojavella Pellmyr, 1999 (Lepidoptera: Prodoxidae). Yucca valida Brandegee (Asparagales: Asparagaceae) is distributed in the central region, whereas Yucca capensis L.W. Lenz, 1998 (Asparagales: Asparagaceae) occurs in the southern part of the peninsula. Both Y. valida and Y. capensis are pollinated by Tegeticula baja Pellmyr, Balcázar-Lara, Segraves, Althoff & Littlefield, 2008 (Lepidoptera: Prodoxidae; Lenz, 1998; Turner et al., 1995). Furthermore, a region of hybrid populations of Y. valida and Y. capensis has been identified, both pollinated by T. baja (Arteaga et al., 2020). However, there are no previous records of parasitoid wasps associated with T. baja or T. mojavella populations in the Baja California Peninsula. This study aims to identify the genera of parasitic wasps associated with Tegeticula species in the peninsula. We also investigate whether the use of different hosts, such as T. mojavella and T. baja, and the environmental distribution of the wasps lead to phenotypic and genetic differentiation in the wasp populations.

Materials and methods

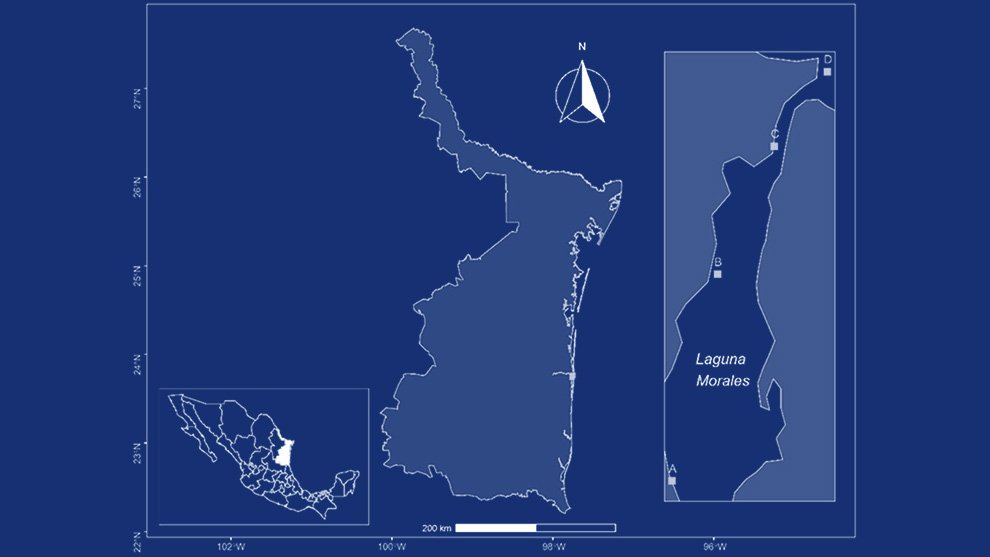

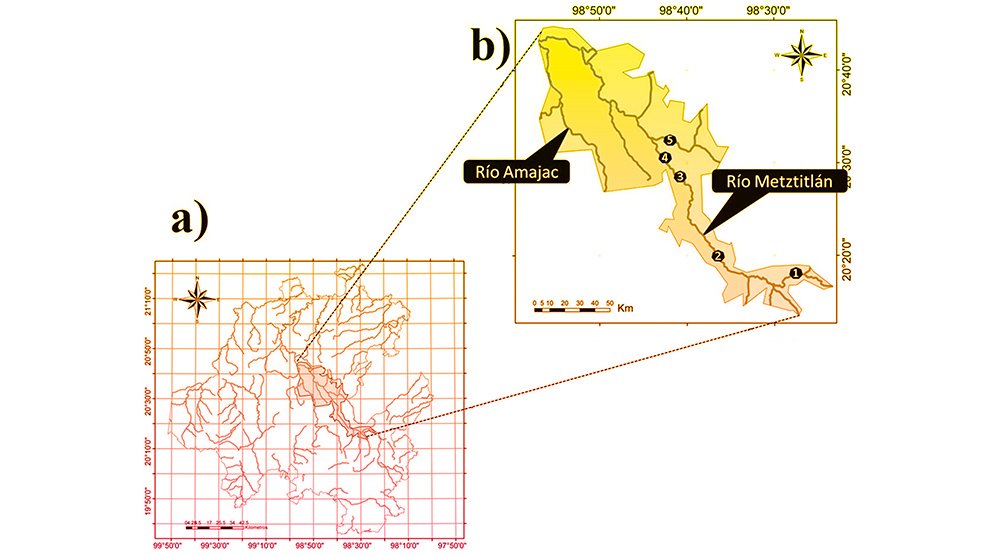

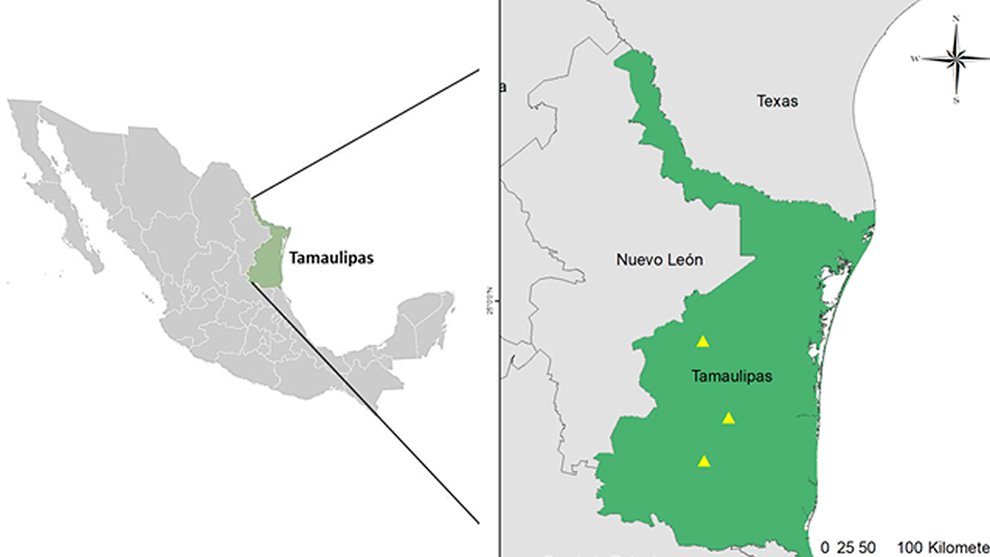

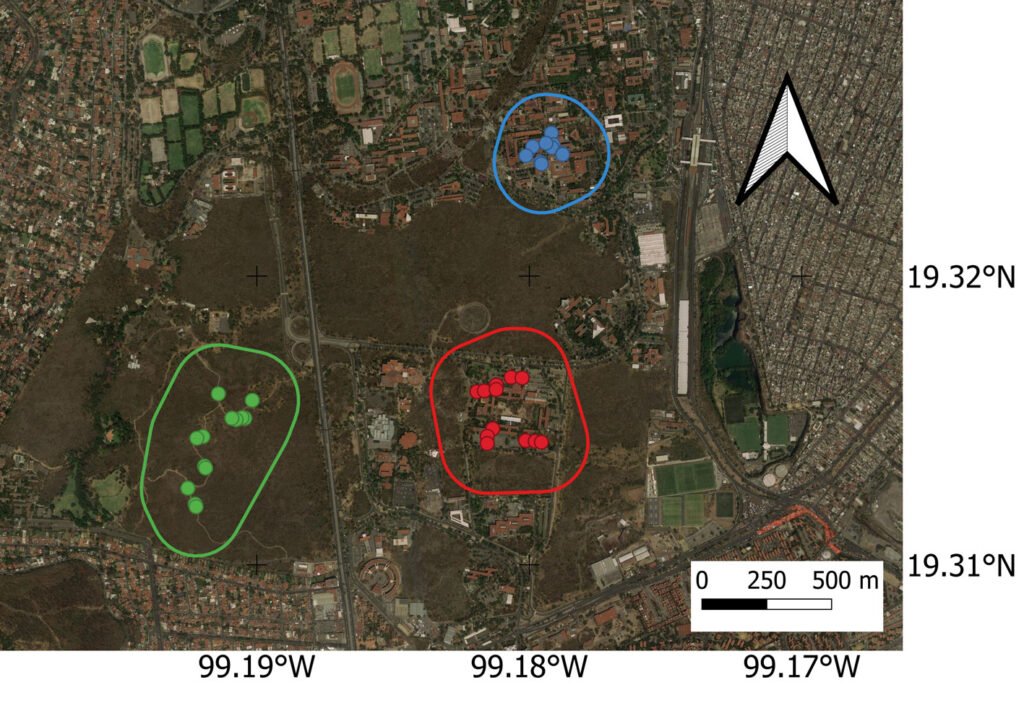

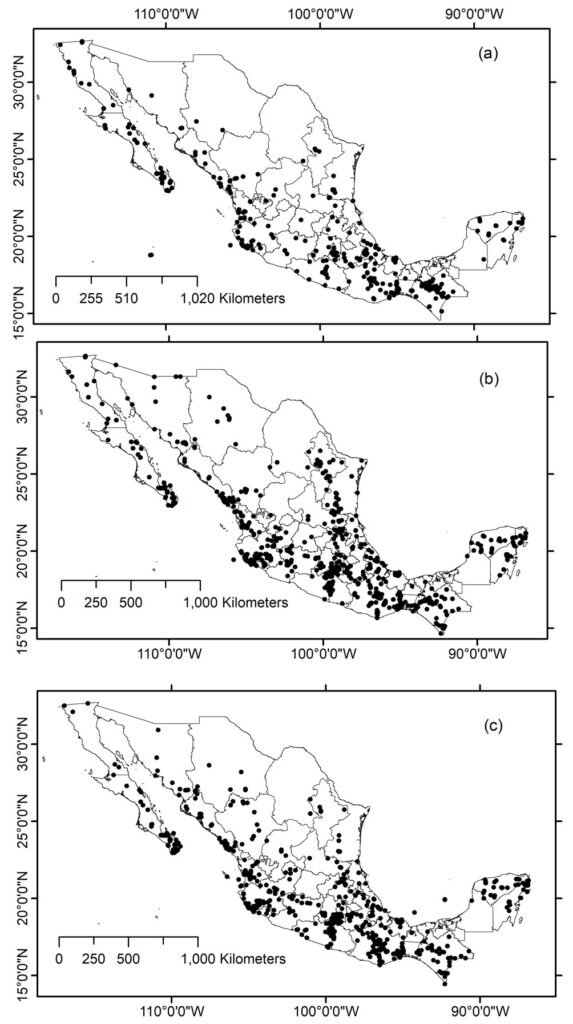

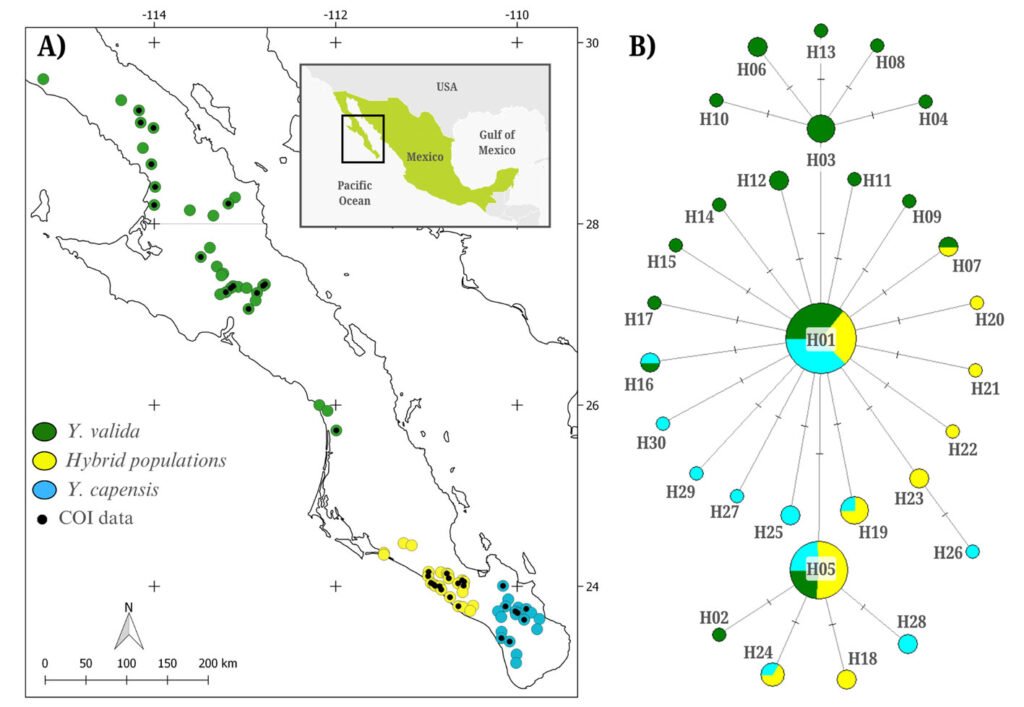

We visited 35 locations in the Baja California Peninsula, following the distribution of the Yucca species and their pollinators T. mojavella and T. baja (Fig. 1A, Table S1). Specifically, we surveyed 12 locations in the northern section of the peninsula, where Yucca schidigera occurs, within forest habitats of Sierra Juárez (N = 6), Sierra San Pedro Mártir (N = 4), and Chaparral (N = 2). We visited 11 locations within the central desert of the peninsula where Yucca valida are distributed. Finally, we collected samples from 12 locations in the south section of the peninsula. Eight locations were in the coastal plains of the Magdalena Plains region, where populations of Y. valida x Y. capensis are found. The remaining 4 locations were in the deciduous lowland forest of the Cape Region, where Y. capensis populations are present.

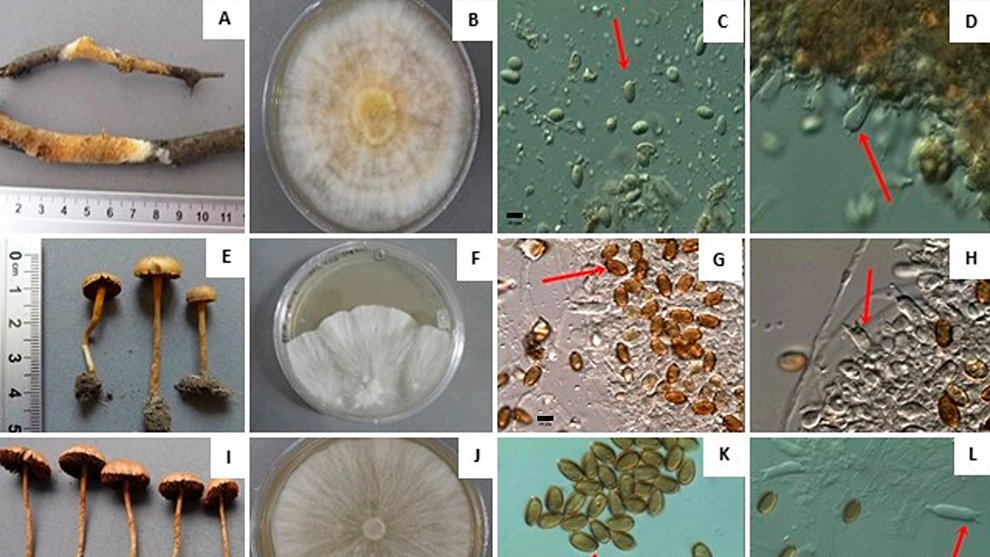

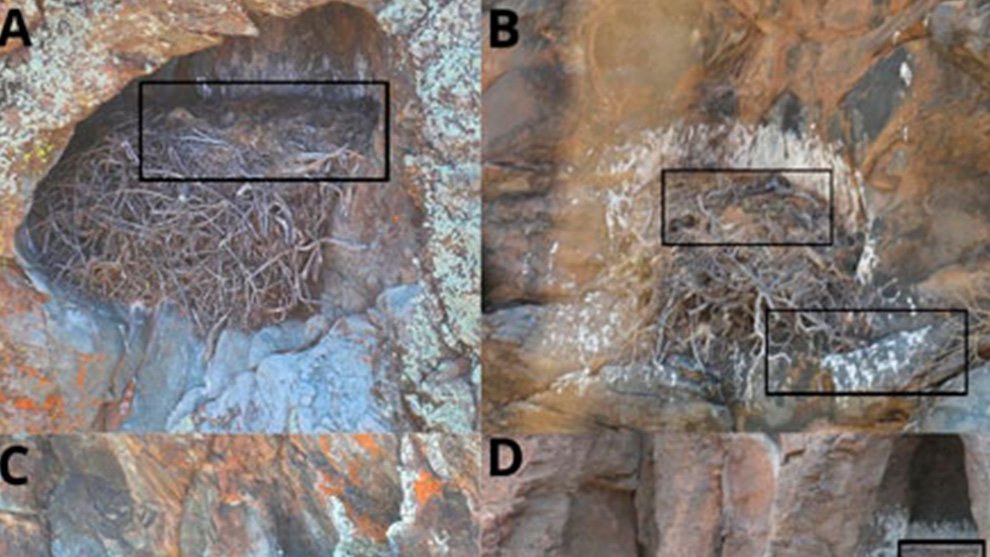

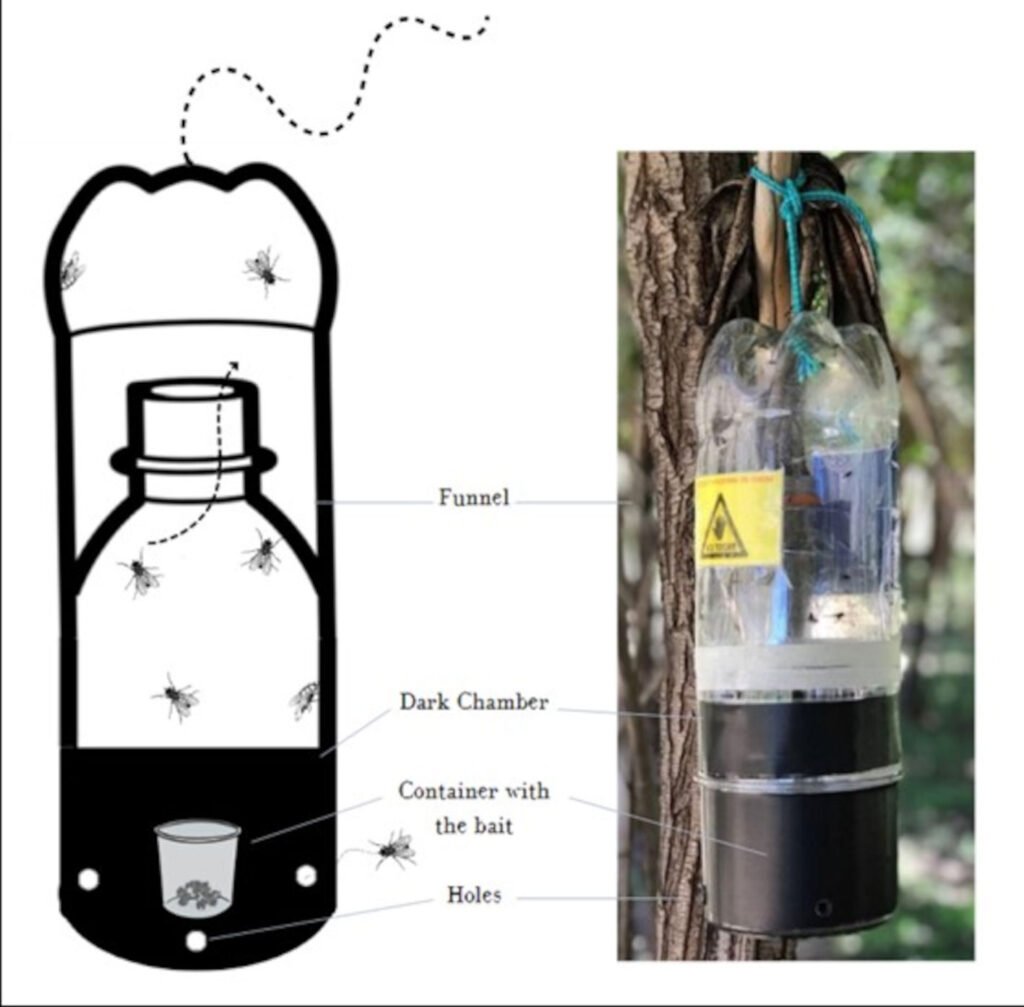

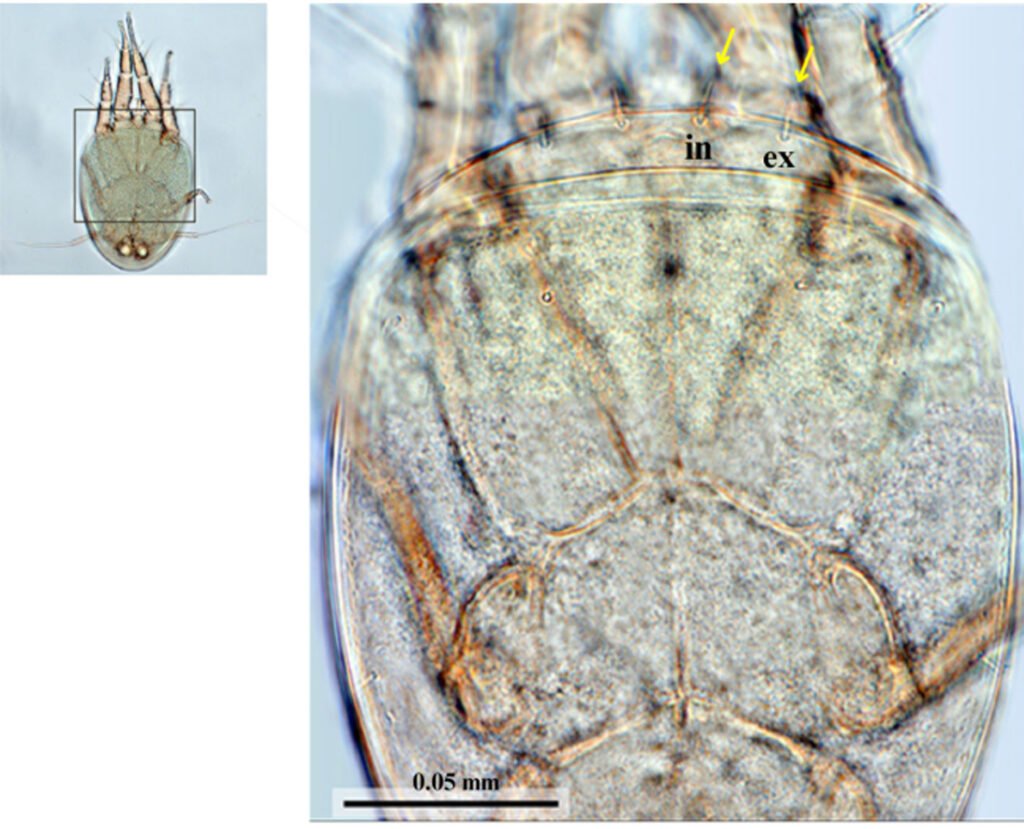

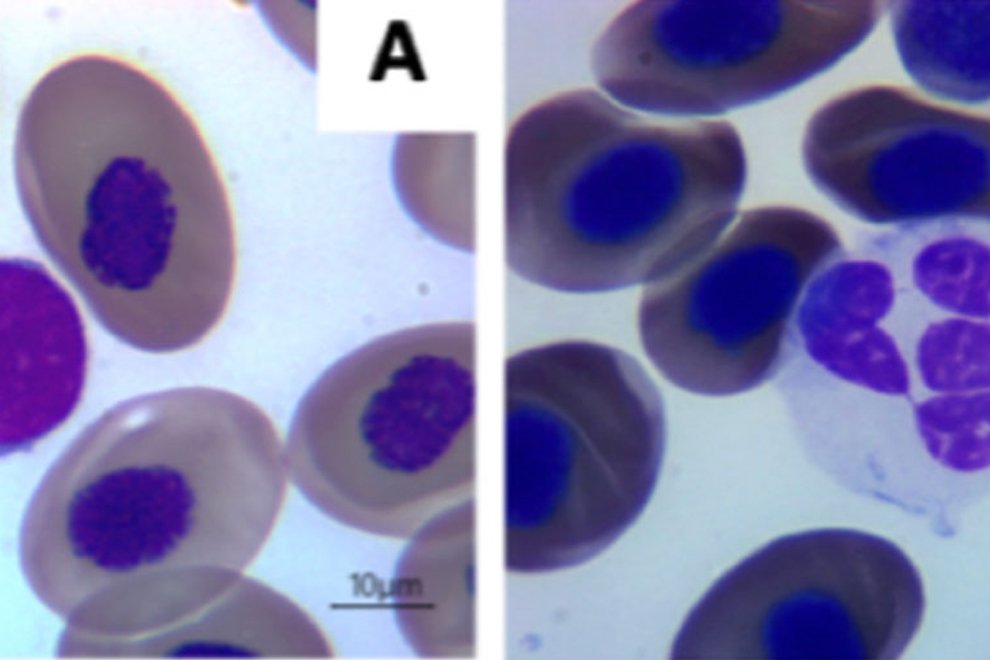

Each location was visited once between 2013 to 2015, during the fruiting season of the Yucca species. We selected approximately 10 trees per location, gathering 3 to 5 fruits from each tree. The mature fruits were collected directly from Yucca trees and placed individually within 500 ml plastic cups with mesh netting lids. Fruits were transported to the laboratory and stored in rooms at environmental conditions (approximately 25°C and 60% relative humidity). For 2 weeks, we checked each plastic cup daily for adult wasps. All adult wasps that emerged from the fruits were collected and placed in 20 ml glass vials. Following another 2 weeks, we dissected the fruits to obtain wasps pupae. All wasps were preserved in glass vials with 96% ethanol and labeled with locality and host plant species. Adult individuals were observed with a Nikon SMZ745-T stereomicroscope equipped with Lumenera’s INFINITY digital camera, and identified to genus taxonomic level using the dichotomous key provided by Sánchez et al. (1998). Two genera of parasitoid wasps from the Braconidae family were identified (Fig. 2): Bassus Fabricius, 1804 and Digonogastra Viereck, 1912.

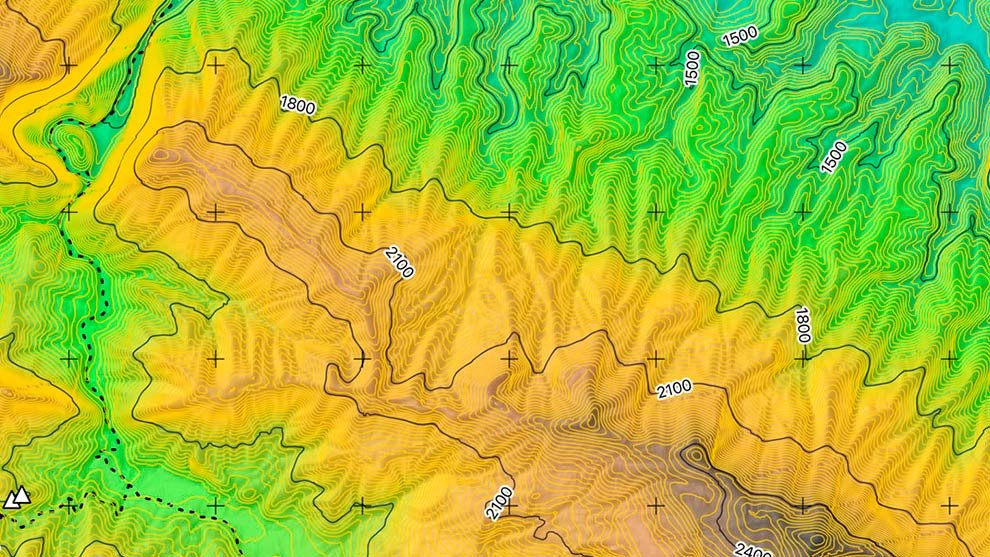

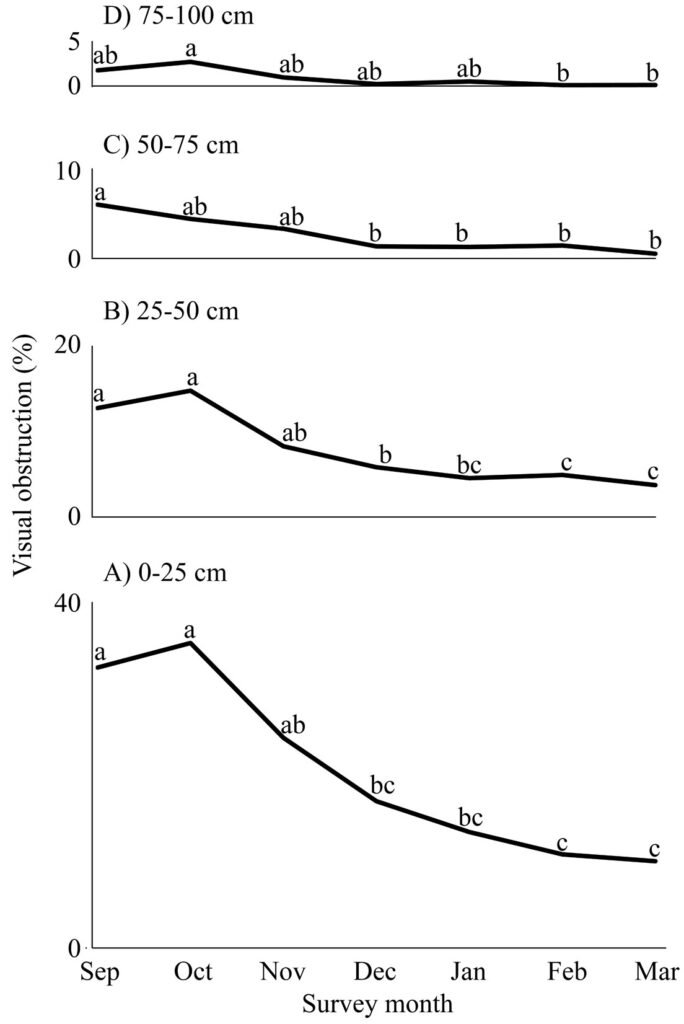

Figure 1. A, Localities sampled of Digonogastra sp. in the Baja California Peninsula. The geographical distribution is marked using colors and the host moth species is indicated whit shapes; B, haplotype network. The geographical distribution is marked using colors and the host moth species with lines; C, graph depicting the observed and simulated distribution of paired sequence differences.

Figure 2. The genera of parasitoid wasps sampled from yucca fruits in the Baja California Peninsula. On the upper side is the genus Digonogastra; on the bottom is Bassus.

DNA extraction and molecular marker amplification. We extracted DNA from 119 wasps using the commercial Qiagen DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit. The sample consisted of 114 adult individuals and 5 in the pupal stage. A fragment of the Cytochrome Oxidase subunit I (COI) marker was amplified via PCR using the universal primers for invertebrates described by Folmer et al. (1994); LCO1490 (5’-GGTCAACAAATCATAAAGATATTGG-3’) and HCO2198 (5’-TAAACTTCAGGGTG ACCAAAAAATCA-3’). The PCR mixture included 5 µl of Buffer (1x), 1.5 µl of MgCL (2.5mM), 0.3 µl of dNTPs (0.16mM), 0.6 µl of each primer at 10 µM, 0.2 µl of Taq polymerase (1 unit), 1 µl of DNA, and 5.8 µl of molecular-grade water, resulting in a 15 µl reaction volume.

The thermal cycler was set up with the following conditions: an initial denaturation at 94 ºC for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 ºC for 1 min, annealing at 50 ºC for 1 min, and extension at 68 ºC for 1 min. A final elongation step was performed at 72 ºC for 5 min. Amplification quality was confirmed using 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. The PCR products were sequenced by SeqXcel (www.seqxcel.com) for further analysis.

Genetic diversity and population genetic structure. The sequences were visualized, aligned, and edited using the BioEdit software (Hall, 1999). Sequences from individuals identified morphologically were submitted to BLAST to confirm the parasitoid genus (Blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). The sample size of Digonogastra sp. (N = 111) allowed for diversity and population structure analysis. The genetic diversity of Digonogastra species was assessed using DNAsp software (Rozas et al., 2003). This involved calculating the number of haplotypes, haplotype diversity, and nucleotide diversity (Nei & Li, 1979; Nei, 1987). To investigate the genealogical relationships among the identified haplotypes, we constructed a haplotype network using the Median-Joining method in NETWORK 5.0 software (Bandelt et al., 1999). We constructed a phylogenetic tree using the haplotypes obtained for Digonogastra sp. to determine whether the detected diversity in the Baja California Peninsula is unique to this region or present elsewhere. We included sequences available in the NCBI from Canada. The genera Alabagrus (Sharkey & Chapman, Unpublished; GenBank: MF361682.1) and Cotesia (Hebert et al., 2016) were employed as outgroups. The tree was constructed using the Maximum Likelihood method, with 1000 bootstrap replicates and the HKY+I substitution model, which showed the best fit to the data (highest AIC value), as determined by the jModelTest program (Darriba et al., 2012).

To assess genetic differentiation of Digonogastra spp. across its geographical distribution in the peninsula, we conducted 3 Molecular Variance Analyses (AMOVA). First, we examined how geographical distances affected the distribution of genetic diversity. We divided the data into 3 categories based on their location in the peninsula: north, center, and south (Fig. 1A). Then, we assessed whether genetic differentiation was due to environmental factors, grouping the data based on their ecoregion of origin. We based our categorization on the ecoregions proposed by Gonzales-Abraham et al. (2010). Lastly, our third analysis examined whether genetic differentiation was related to the host, grouping the data based on the host moths, T. mojavella and T. baja. The ARLEQUIN software (Excoffier et al., 2005) was employed for these analyses.

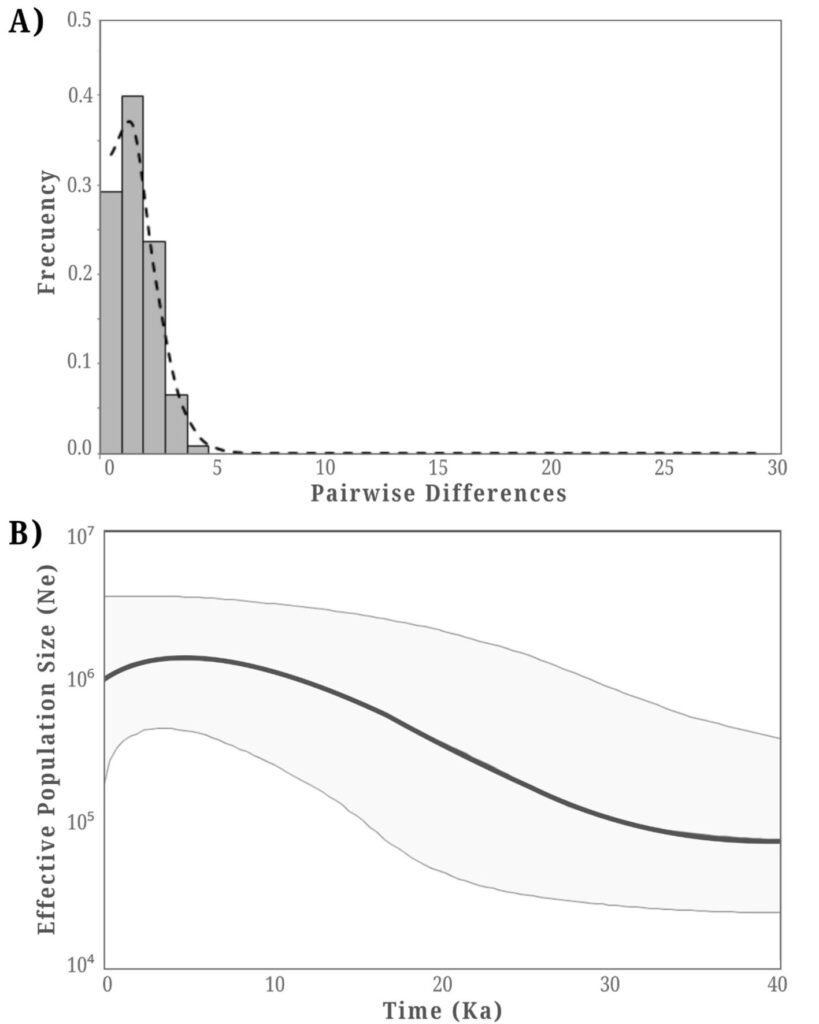

We evaluated historical demographic changes in the wasp population using the pairwise sequence differences distribution analysis (mismatch analysis) performed in the ARLEQUIN software. The shape of the mismatch distribution is used to infer whether a population expansion has occurred (Rogers & Harpending, 1992). A unimodal distribution indicates population expansion, while a multimodal distribution suggests a stable population size. Additionally, the sum of squared deviations (SSD) is employed to validate the expansion model (Navascués et al., 2006). A significant SSD (p < 0.05) rejects the population expansion model.

Phenotypic variation. Phenotypic variation of the parasitoid wasps was evaluated by measuring 106 adult

individuals of the Digonogastra genus (excluding individuals in the pupal stage). No morphometric analyses were conducted for Bassus specimens due to their small sample size (N = 8). Measurements of the 106 adults were conducted with Infinity Analyze software (Lumenera, Canadá), calibrated in millimeters and verified with a conventional ruler. We measured 18 external morphological characters of the adult individuals (Table 1). Measurements were taken on the left side of the individuals and included the length from the head to the end of the last metasoma segment, the scape width, antenna length, mesosoma (thorax) and metasoma (abdomen) width and length, femur width, total leg length, anterior wing length, and the length of 5 wing vein components: C+SC+R, 1RS, (RS+M)a, 2RS, and r-rs. For females, we also measured the length and width of the ovipositor and the length of the ovipositor apex (Table 1). We calculated the mean, standard deviation, and coefficient of variation of each measured character. A correlation matrix was created using the Pearson Correlation Coefficient (r) between pairs of characters, determining the significance values (p) for each correlation. All morphometric measurements were analyzed with JMP 5.01 software (SAS Cary, New Jersey, USA).

We assessed 3 potential sources of variation for the phenotypic differentiation among parasitoid wasps in the Baja California Peninsula: sexual dimorphism, the ecoregions in which they are distributed, and the host species of Tegeticula moths. We conducted a Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA) for each factor using all measured characters. We also performed an Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to determine which trait contributes significantly to phenotypic differences. Each wasp was assigned to an ecoregion based on its geographical origin (Gonzales-Abraham et al., 2010). The wasps were found in 6 ecoregions: Sierra Juárez, Sierra San Pedro Mártir, Chaparral, Central Desert, Magdalena Plains, and Cape Lowland Forest.

Results

We collected a total of 119 parasitoid wasps from 35 locations across the Baja California Peninsula (Fig. 1A, Table S1). Two genera of parasitoid wasps belonging to the Braconidae family were collected: Bassus and Digonogastra. Eight female individuals of Bassus sp. (6.7%) emerged from fruits in 2 different locations. Seven Bassus specimens were collected in Y. valida fruits, while 1 emerged from Y. capensis. All these fruits contained T. baja larvae. In contrast, we collected 111 Digonogastra individuals (93.3%), with 68 males and 38 females from 33 different sites across 32.58° to 23.38° N latitude. Out of these, 57 individuals of Digonogastra sp. emerged from Y. schidigera fruits where T. mojavella was also found. The remaining 54 individuals were found in Y. valida, Y. valida x Y. capensis, and Y. capensis fruits, where T. baja larvae were also present.

Table 1

Mean (M), standard deviation (SD), and coefficient of variation in percentage (CV) of the evaluated morphological traits in female and male individuals of Digonogastra sp. in the Baja California Peninsula. The results of the analysis of variance (ANOVA) performed for sexual dimorphism (S), ecoregions (E), and host (H) are presented with significance levels denoted as follows: p > 0.05 (ns), p < 0.05 (*), and p < 0.0001 (***).

| Trait | Female | Male | ANOVA | ||||||

| M | SD | CV | M | SD | CV | S | E | H | |

| Body length: | 9.03 | 1.29 | 14.24 | 7.34 | 1.47 | 20.04 | *** | * | ns |

| Antenna: | |||||||||

| Total length | 6.88 | 0.73 | 10.58 | 6.16 | 1.08 | 17.52 | *** | * | ns |

| Escapo width | 0.24 | 0.03 | 12.61 | 0.19 | 0.04 | 22.92 | *** | ns | ns |

| Leg: | |||||||||

| Total length | 6.97 | 0.90 | 12.96 | 5.21 | 1.08 | 20.67 | *** | * | ns |

| Femur width | 0.52 | 0.06 | 12.23 | 0.36 | 0.08 | 22.93 | *** | * | ns |

| Mesosoma: | |||||||||

| Lateral width | 2.17 | 0.32 | 14.54 | 1.61 | 0.34 | 21.11 | *** | ns | ns |

| Lateral length | 3.17 | 0.45 | 14.08 | 2.46 | 0.58 | 23.59 | *** | * | ns |

| Metasoma: | |||||||||

| Lateral width | 2.14 | 0.56 | 26.32 | 1.33 | 0.44 | 33.15 | *** | * | ns |

| Lateral length | 4.84 | 0.81 | 16.83 | 4.03 | 0.86 | 21.20 | *** | * | ns |

| Wing: | |||||||||

| Total length | 8.47 | 0.95 | 11.19 | 6.30 | 1.26 | 19.96 | *** | * | ns |

| C+SC+R length | 3.99 | 0.48 | 12.14 | 3.03 | 0.62 | 20.62 | *** | * | ns |

| 1RS length | 0.26 | 0.04 | 15.15 | 0.21 | 0.05 | 23.26 | *** | ns | ns |

| (RS+M)a length | 1.00 | 0.13 | 12.46 | 0.70 | 0.15 | 21.33 | *** | * | ns |

| 2RS length | 0.69 | 0.10 | 13.98 | 0.51 | 0.10 | 18.78 | *** | * | ns |

| r-rs length | 0.29 | 0.05 | 17.53 | 0.21 | 0.05 | 21.47 | *** | * | ns |

| Ovipositor: | |||||||||

| Total length | 8.37 | 1.07 | 12.84 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ns | ns |

| Lateral width | 0.06 | 0.01 | 10.54 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ns | ns |

| Apex length | 0.36 | 0.05 | 14.22 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ns | ns |

Genetic diversity and population genetic structure. We obtained a 632 bp sequence for each of the 8 individuals of Bassus sp. These sequences did not exhibit site variability, defining them as a single haplotype. Further analyses were not conducted due to the lack of variation. Compared to NCBI sequences, they showed 97% coverage, an E-value of 0.0, and 97.73% identity with the genus Bassus.

The alignment of the 111 Digonogastra wasps allows us to obtain 563 bp and reveals 7 variable sites. We obtained 100% coverage, 0.0 E-value, and 93.61% identity compared with NCBI sequences. Nucleotide diversity (Pi) for Digonogastra sp. in the peninsula was 0.00228, and haplotype diversity (Hd) was 0.775. The 7 variable sites defined 11 haplotypes. Haplotype 2 was most abundant, followed by haplotypes 4, 7, and 1 (Fig. 1B). Six of the 11 haplotypes were found throughout the entire geographic range, 3 were unique to the northern region, and 2 were only found in the central part of the peninsula. The phylogenetic analysis revealed that 11 haplotypes from the peninsula formed a single clade with 100% support (Fig. S1). This clade was separated from 5 clades found in Canada, although with low bootstrap support (43%).

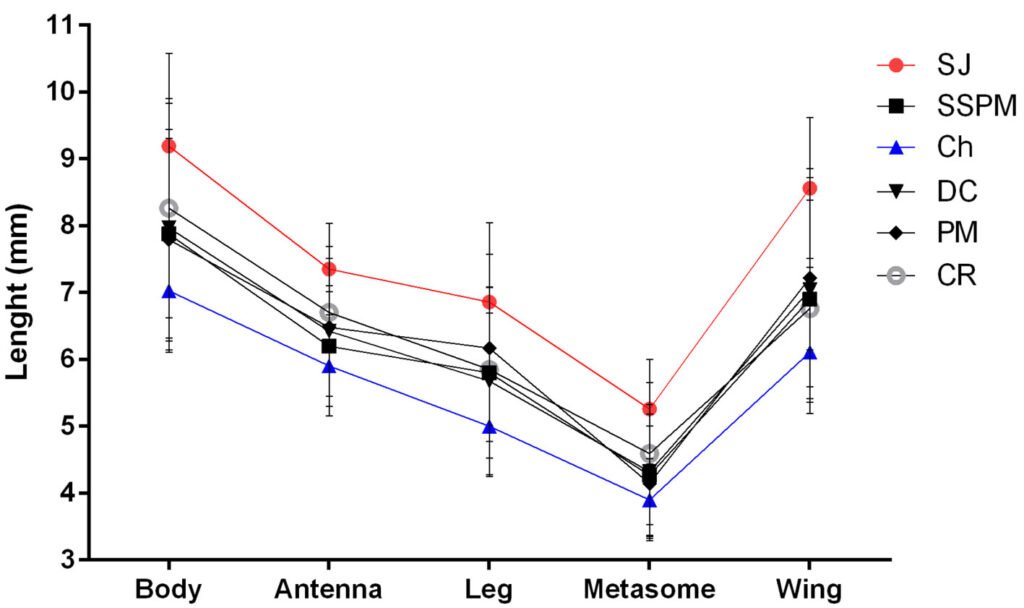

Figure 3. Mean and standard deviation of 5 significantly different traits of Digonogastra sp. among Baja California Peninsula ecoregions. From north to south, they are listed as follows: Sierra Juárez (SJ), Sierra San Pedro Mártir (SSPM), Chaparral (Ch), Central Desert (DC), Magdalena Plains (PM), and Cape Region (CR). Individuals with larger sizes are marked in red, while those with smaller sizes are marked in blue.

The geographical distance did not cause genetic differentiation in Digonogastra sp. individuals (Fst = -0.01319, S.S. = 41.176, p = 0.84360 ± 0.01326). Similarly, no differentiation was found between individuals inhabiting different ecoregions (Fst = -0.01838, S.S. = 38.933, p = 0.05181 ± 0.00599) and individuals parasitizing different host species (Fst = 0.01877, S.S. = 41.853, p = 0.06158 ± 0.00750). Considering that Digonogastra sp. individuals from the peninsula form a single genetic clade, we performed a demographic analysis (i.e., mismatch analysis), including all individuals as a single population. The distribution of paired differences was unimodal, and the SSD test did not reject the expansion hypothesis (p = 0.09).

Phenotypic variation. Digonogastra sp. females had an average body length of 9.03 mm, with their morphological characters showing coefficients of variation between 10% and 27%. Males had an average body length of 7.34 mm, with morphological characters exhibiting coefficients of variation between 17% and 33%. The most variable character was the metasoma width for females and males, with coefficients of variation of 26.32% and 33.15%, respectively. Females exhibited significant correlations between all analyzed traits (r² > 0.6; p < 0.05), except for ovipositor width, ovipositor tip length, and scape width (r² < 0.3; p > 0.05), while males showed significant correlations across all traits (Fig. S2).

Morphological differences between males and females were significant (F test = 5.21, F = 25.74, p < 0.0001), with females being consistently larger in all measured characters (Table 1). Similarly, significant differences were found among individuals from different ecoregions (Wilks’ Lambda = 0.195, F = 1.83, p < 0.0002; Table 1, Fig. 3), with 11 out of 18 characters showing high variation (Table 1). Finally, significant differences observed in the MANOVA (F test = 0.40, F = 1.98, p < 0.027) indicate that the traits of the wasps vary according to the host groups, even though the ANOVA did not detect significant differences in individual traits (Table 1).

Discussion

The taxonomic, genetic, and phenotypic diversity of parasitoid wasps is influenced by environmental and spatial distribution of their populations and hosts (Althoff & Thompson, 2001; Baer et al., 2004; Harrison et al., 2022). Here, we have recorded for the first time Bassus wasps attacking Tegeticula moths. Additionally, we include the first report of a Digonogastra wasps attacking T. baja. The 111 Digonogastra sp. individuals from various environments showed low genetic diversity across the peninsula, suggesting a single panmictic population that had experienced historical demographic expansion. We also identified sexual dimorphism and morphometric variation due to ecoregions and diferent host.

Genetic diversity estimates for Digonogastra sp. in the Baja California Peninsula are moderate (N = 111, 11 haplotypes, Hd = 0.77, pi = 0.00228). Similar genetic diversity values have been reported for other parasitoid wasps in the Braconidae family (Baer et al., 2004; Hufbauer et al., 2004). For Digonogastra sp., we obtained values of reduced nucleotide diversity alongside high haplotype diversity, indicating that population haplotypes are very similar to each other, as shown in our haplotype network (Fig. 1B). This pattern is observed in species that have experienced population expansion events (Roderick, 1996). Individuals from the Baja California Peninsula have different haplotypes than those recorded to the north of the genus’s distribution, and they cluster into a different clade from the haplotypes reported in Canada (Fig. S1). Future sampling in intermediate areas will help determine whether the diversity found in this study is shared with other zones of their distribution or is restricted to this geographic region.

We found no genetic diversity structuring Digo-

nogastra sp. individuals from different geographic areas, ecoregions, or hosts (i.e., Tegeticula spp.) in the Baja California Peninsula. Furthermore, Digonogastra individuals share most of the recorded haplotypes, suggesting a single panmictic population. A similar pattern was observed in the parasitoid wasp Eusandalum sp., which attacked 11 species of Prodoxus spp. moths in a Yucca complex, in the USA (Althoff, 2008). These 2 wasp genera are known for their generalist nature, which may be related to the genetic differentiation pattern across the landscape. Eusandalum sp., in particular, can lay eggs throughout the year and parasitize any available Prodoxus species, which helps to maintain a continuous population across the landscape (Althoff, 2008). Digonogastra has been recorded attacking various Tegeticula and Prodoxus moths (Force & Thompson, 1984), also present in the peninsula (obs. pers; Althoff et al., 2007). Therefore, other potential food sources could contribute to the population connectivity of Digonogastra sp. throughout its distribution. For example, Prodoxus larvae have been observed as a year-round resource (Powell, 1989). However, further studies are needed to confirm the presence of Digonogastra sp. attacking other Tegeticula and Prodoxus species in this region.

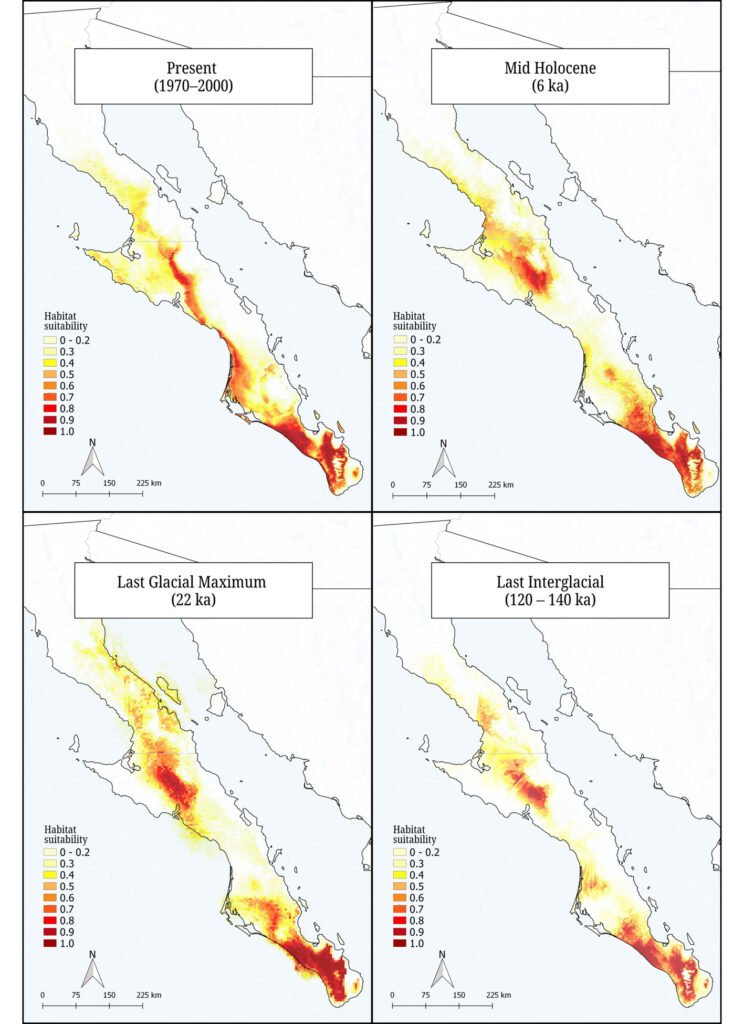

The panmictic population of Digonogastra sp. in the Baja California Peninsula exhibited a historical population expansion, as supported by different analyses (Fig. 1C). The close parasitoid-host interaction with Yucca-pollinating moths implies that demographic changes in their hosts (moths) and in the plants can directly affect the demographics of their populations. Previous studies have recorded the influence of glacial and interglacial cycles in the Quaternary on the demographic history of organisms in the Baja California Peninsula (Garrick et al., 2009; Harrington et al., 2018; Nason et al., 2002). Demographic changes have been documented for the 3 Yucca species in this region, and their habitat has expanded since the last interglacial maximum (Alemán et al., 2024; Arteaga et al., 2020; De la Rosa et al., 2020). Since Digonogastra sp. individuals rely on Yucca plant fruits to complete their life cycle, as these fruits host the moth larvae that serve as their food source, the population expansion found in these wasps may be a consequence of the population expansion observed in the plants that host their hosts.

Phenotypic variability and sexual dimorphism of Digonogastra sp. Geographic variation in phenotype is a common factor in insect populations (Stilwell & Fox, 2007, 2009). The spatial structure of this variation can be determined by environmental conditions, genetic composition, and/or ecological interactions (Agrawal, 2001; Resh & Cardé, 2009; Seifert et al., 2022). For Digonogastra sp. in the Baja California Peninsula, our results show phenotypic variability and a high phenotypic correlation among the studied traits (Table 1, Fig. S2). However, the female ovipositor showed low variation and correlation with the other traits, indicating that its variation did not depend closely on the expression of other traits. Females use the ovipositor to pierce the fruit pericarp, access the moth larvae, and lay eggs (Crabb & Pellmyr, 2006; Resh & Cardé, 2009; Vilhelmsen et al., 2001). The function of this trait is closely related to its fitness, as the arrangement of wasp eggs near moth larvae inside the fruit determines their survival by allowing access to their food source. This may favor reduced variation in ovipositor size (Mazer & Damuth, 2001; Pigliucci, 2003).

Like other parasitoid wasps, Digonogastra sp. exhibits sexual dimorphism (Hurlbutt, 1987; Quicke, 2015), with females being larger in all the traits assessed compared to males (Table 1). Sexual dimorphism in Hymenoptera is partly attributed to complementary sex determination (CSD), where fertilized eggs develop into females and unfertilized eggs into males (Quicke, 2015; Resh & Cardé, 2009). Studies on parasitoid wasps have shown that females typically allocate more resources to fertilized eggs (females) than unfertilized ones (males; Ellers & Jervis, 2003; Jervis et al., 2008; Quicke, 2015; Resh & Cardé, 2009; Visser, 1994). Therefore, the variation in size can be explained by the interplay between CSD and the differential allocation of resources during oviposition.

The environmental heterogeneity in which these wasps are distributed in the Baja California Peninsula also affects their phenotypic variation (Fig. 3). Similar patterns have been observed in butterflies, where species distributed across a broad environmental range exhibit greater variation in organism size compared to species with a more restricted environmental distribution (Seifert et al., 2022). The relationship between body size and environmental variability is attributed to the significant influence of the environment on the development and growth of holometabolous insects, considering factors such as temperature, humidity, and nutrition (Davidowitz et al., 2004; Stillwell & Fox, 2007; Wonglersak et al., 2020). Digonogastra sp. wasps from the Baja California Peninsula occur in different ecosystems, including mountainous areas, deserts, and lowland forests, with variable climatic conditions. However, this study did not investigate the environmental factors that may affect morphological differentiation, which is a topic for future research.

Ecological interactions between plants, herbivores, and parasitoids are significant drivers of biological diversity in terrestrial ecosystems (Schoonhoven et al., 2005). The phenotypic variation in Digonogastra sp. is influenced by the interaction between the wasp, the ecoregion and the host. Tritrophic interactions have shown that a favorable environment for plant growth leads to better nutrition for herbivorous insects, enhancing the development and performance of parasitoids (Han et al., 2019; Pekas & Wäckers, 2020; Schoonhoven et al., 2005). These “bottom-up” cascades have been studied and have shown that the nutritional quality of the plant and the host insect plays a critical role in parasitoids. For instance, it has been observed that parasitoid wasps have increased fitness when they inhabit more fertile soils (Pekas & Wäckers, 2020; Sarfraz et al., 2009). This suggests that the different trophic levels may influence the phenotypic diversity of this wasp, namely the plant and herbivore.

In conclusion, our study records for the first time the genus of parasitoid wasps Bassus attacking Tegeticula moths and increases the diversity of hosts attacked by Digonogastra wasps. The genetic diversity of Digonogastra sp. in the Baja California Peninsula is moderate, forming a single panmictic population with signs of historical demographic expansion. Phenotypic variation is influenced by sexual dimorphism, ecoregions, and their host, this highlights the various factors that can shape the phenotype of these parasitoid wasps. The presence of Digonogastra sp. in different ecoregions suggests the influence of ecological interactions on their phenotypic diversity.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Leonardo de la Rosa, Mario Salazar, José Delgadillo, and Darlene van der Heiden for their help with laboratory analysis, technical support, and assistance in the fieldwork. C.R.A.H thanks the Centro de Investigación Científica y Educación Superior de Ensenada (CICESE) and Universidad Autónoma de Baja California (UABC) for offering academic support. This study was supported financially by Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (Conacyt) (CB-2014-01-238843, infra-2014-1-226339). The Rufford Foundation also provided financial support for a part of this study (RSG 13704-1) and the Jiji Foundation. The authors thank the Associate Editor and the anonymous reviewer for their valuable comments. The authors do not have any conflict of interest to declare.

Haplotypes from this study were deposited in the GenBank with accession numbers PQ252653-PQ252665.

References

Abdala-Roberts, L., Puentes, A., Finke, D. L., Marquis, R. J., Montserrat, M., Poelman, E. H. et al. (2019). Tri-trophic interactions: bridging species, communities and ecosystems. Ecology Letters, 22, 2151–2167. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13392

Agrawal, A. A. (2001). Phenotypic plasticity in the interactions and evolution of species. Science, 294, 321–326. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1060701

Althoff, D. M., & Thompson, J. N. (2001). Geographic structure in the searching behaviour of a specialist parasitoid: combining molecular and behavioural approaches. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 14, 406–417. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1420-9101.2001.00286.x

Althoff, D. M., Svensson, G. P., & Pellmyr, O. (2007). The influence of interaction type and feeding location on the phylogeographic structure of the yucca moth community associated with Hesperoyucca whipplei. Molecular Phy-

logenetics and Evolution, 43, 398–406. https://doi.org/10.

1016/j.ympev.2006.10.015

Althoff, D. M. (2008). A test of host-associated differentiation across the ‘parasite continuum’in the tri-trophic interaction among yuccas, bogus yucca moths, and parasitoids. Molecular Ecology, 17, 3917–3927. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03874.x

Althoff, D. M., Segraves, K. A., Smith, C. I., Leebens-Mack, J., & Pellmyr, O. (2012). Geographic isolation trumps coevolution as a driver of yucca and yucca moth diversification. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 62, 898–906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2011.11.024

Althoff, D. M., & Segraves, K. A. (2022). Evolution of antag-

onistic and mutualistic traits in the yucca-yucca moth obligate pollination mutualism. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 35, 100–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/jeb.13967

Arteaga, M. C., Bello-Bedoy, R., & Gasca-Pineda, J. (2020). Hybridization between yuccas from Baja California: Genomic and environmental patterns. Frontiers in Plant Science, 11, 685. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2020.00685

Baer, C. F., Tripp, D. W., Bjorksten, T. A., & Antolin, M. F. (2004). Phylogeography of a parasitoid wasp (Diaeretiella rap-

ae): no evidence of host-associated lineages. Molecular Ecology, 13, 1859–1869. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.

2004.02196.x

Bandelt, H. J., Forster, P., & Röhl, A. (1999). Median-joining networks for inferring intraspecific phylogenies. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 16, 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026036

Carmona, D., Fitzpatrick, C. R., & Johnson, M. T. (2015). Fifty years of co-evolution and beyond: integrating co-evolution from molecules to species. Molecular Ecology, 24, 5315–5329. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.13389

Crabb, B. A., & Pellmyr, O. (2006). Impact of the third trophic level in an obligate mutualism: do yucca plants benefit from parasitoids of yucca moths? International Journal of Plant Sciences, 167, 119–124. https://doi.org/10.1086/497844

Cuautle, M., & Rico-Gray, V. (2003). The effect of wasps and ants on the reproductive success of the extrafloral nectaried plant Turnera ulmifolia (Turneraceae). Functional Ecology, 17, 417–423. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2435.2003.00732.x

Darriba, D., Taboada, G. L., Doallo, R., & Posada, D. (2012). jModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nature Methods, 9, 772. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.2109

Davidowitz, G., D’Amico, L. J., & Nijhout, H. F. (2004). The effects of environmental variation on a mechanism that controls insect body size. Evolutionary Ecology Research, 6, 49–62.

De la Rosa-Conroy, L., Gasca-Pineda, J., Bello-Bedoy, R., Eguiarte, L. E., & Arteaga, M. C. (2020). Genetic patterns and changes in availability of suitable habitat support a colonization history of a North American perennial plant. Plant Biology, 22, 233–242. https://doi.org/10.1111/plb.13053

Ellers, J., & Jervis, M. (2003). Body size and the timing of egg production in parasitoid wasps. Oikos, 102, 164–172. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0706.2003.12285.x

Engelmann, G. (1872). The flower of yucca and its fertilization. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club, 3, 33–33.

Excoffier, L., Laval, G., & Schneider, S. (2005). Arlequin (version 3.0): an integrated software package for population genetics data analysis. Evolutionary Bioinformatics Online, 2005,47–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/117693430500100003

Folmer, O., Hoeh, W. R., Black, M. B., & Vrijenhoek, R. C. (1994). Conserved primers for PCR amplification of mitochondrial DNA from different invertebrate phyla. Molecular Marine Biology and Biotechnology, 3, 294–299.

Force, D. C., & Thompson, M. L. (1984). Parasitoids of the immature stages of several southwestern yucca moths. The Southwestern Naturalist, 29, 45–56. https://doi.org/

10.2307/3670768

Garrick, R. C., Nason, J. D., Meadows, C. A., & Dyer, R. J. (2009). Not just vicariance: phylogeography of a Sonoran Desert euphorb indicates a major role of range expansion along the Baja peninsula. Molecular Ecology, 18, 1916–1931. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04148.x

Godfray, H. C. J. (1994). Parasitoids: behavioral and evolut-

ionary ecology. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

González-Abraham, C. E., Garcillán, P. P., & Ezcurra, E. (2010). Ecorregiones de la península de Baja California: una síntesis. Boletín de la Sociedad Botánica de México, 87, 69–82. https://doi:10.17129/botsci.302

Hall, T. A. (1999). BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symposium Series, 41,95–98.

Han, P., Desneux, N., Becker, C., Larbat, R., Le Bot, J., Adamowicz, S. et al. (2019). Bottom-up effects of irrigation, fertilization and plant resistance on Tuta absoluta: implications for Integrated Pest Management. Journal of Pest Science, 92, 1359–1370. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-018-1066-x

Harrington, S. M., Hollingsworth, B. D., Higham, T. E., & Reeder, T. W. (2018). Pleistocene climatic fluctuations drive isolation and secondary contact in the red diamond rattlesnake (Crotalus ruber) in Baja California. Journal of Biogeography, 45, 64–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.13114

Harrison, K., Tarone, A. M., DeWitt, T., & Medina, R. F. (2022). Predicting the occurrence of host-associated differentiation in parasitic arthropods: a quantitative literature review. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata, 170, 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/eea.13123

Hebert, P. D., Ratnasingham, S., Zakharov, E. V., Telfer, A. C., Levesque-Beaudin, V., Milton, M. A. et al. (2016). Counting animal species with DNA barcodes: Canadian insects. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 371, 20150333. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0333

Heil, M. (2008). Indirect defence via tritrophic interactions.

New Phytologist, 178, 41–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-

8137.2007.02330.x

Hufbauer, R. A., Bogdanowicz, S. M., & Harrison, R. G. (2004). The population genetics of a biological control introduction: mitochondrial DNA and microsatellie variation in native and introduced populations of Aphidus ervi, a parisitoid wasp. Molecular Ecology, 13, 337–348. https://doi.org/10.

1046/j.1365-294X.2003.02084.x

Hurlbutt, B. (1987). Sexual size dimorphism in parasitoid wasps. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 30, 63–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8312.1987.tb00290.x

Jervis, M. A., Ellers, J., & Harvey, J. A. (2008). Resource acquisition, allocation, and utilization in parasitoid reproductive strategies. Annual Review of Entomology, 53,361–385. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ento.53.103106.093

433

Kankare, M., Van Nouhuys, S., & Hanski, I. (2005). Genetic divergence among host-specific cryptic species in Cotesia melitaearum aggregate (Hymenoptera: Braconidae), parasitoids of checkerspot butterflies. Annals of the Entomological Society of America, 98, 382–394. https://doi.org/10.1603/0013-8746(2005)098[0382:GDAHCS]2.0.CO;2

Kappers, I. F., Hoogerbrugge, H., Bouwmeester, H. J., & Dicke, M. (2011). Variation in herbivory-induced volatiles among cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) varieties has consequences for the attraction of carnivorous natural enemies. Journal of Chemical Ecology, 37, 150–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10886-011-9906-7

Karns, G. (2009). Genetic differentiation of the parasitoid, Cotesia congregata (Say), based on host-plant complex (M. Sc. Thesis). Virginia Commonwealth University. VA, USA. https://doi.org/10.25772/1E5V-N037

Lenz, L. W. (1998). Yucca capensis (Agavaceae, Yuccoideae), a new species from Baja California Sur, Mexico. Cactus and Succulent Journal, 70, 289–296.

Lozier, J. D., Roderick, G. K., & Mills, N. J. (2009). Molecular markers reveal strong geographic, but not host associated, genetic differentiation in Aphidius transcaspicus, a parasitoid of the aphid genus Hyalopterus. Bulletin of Entomological Research, 99, 83–96. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007485308006147

Mazer, S. J., & Damuth, J. (2001). Nature and causes of variation. In C. W. Fox, D. A. Roff, & D. J. Fairbairn (Ed). Evolutionary ecology: concepts and case studies (pp. 3–15). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Nason, J. D., Hamrick, J. L., & Fleming, T. H. (2002). Historical vicariance and postglacial colonization effects on the evolution of genetic structure in Lophocereus, a Sonoran Desert columnar cactus. Evolution, 56, 2214–2226. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0014-3820.2002.tb00146.x

Navascués, M., Vaxevanidou, Z., González-Martínez, S. C., Climent, J., Gil, L., & Emerson, B. C. (2006). Chloroplast microsatellites reveal colonization and meta-

population dynamics in the Canary Island pine. Molecular Ecology, 15, 2691–2698. https://doi.org/10.1111/

j.1365-294X.2006.02960.x

Nei, M., & Li, W. H. (1979). Mathematical model for studying genetic variation in terms of restriction endonucleases. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 76, 5269–5273. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.76.10.5269

Nei, M. (1987). Molecular evolutionary genetics. New York: Columbia University Press.

Pekas, A., & Wäckers, F. L. (2020). Bottom-up effects on tri-trophic interactions: Plant fertilization enhances the fitness of a primary parasitoid mediated by its herbivore host. Journal of Economic Entomology, 113, 2619–2626. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/toaa204

Pellmyr, O., & Leebens-Mack, J. (1999). Forty million years of mutualism: evidence for Eocene origin of the yucca-yucca moth association. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 96, 9178–9183. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.96.

16.9178

Pellmyr, O. (2003). Yuccas, yucca moths, and coevolution: a review. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden, 90, 35–55. https://doi.org/10.2307/3298524

Pigliucci, M. (2003). Phenotypic integration: studying the ecology and evolution of complex phenotypes. Ecology Letters, 6, 265–272. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1461-0248.2003.00428.x

Powell, J. A. (1989). Synchronized, mass-emergences of a yucca moth, Prodoxus Y-inversus (Lepidoptera: Prodoxidae), after 16 and 17 years in diapause. Oecologia, 81, 490–493. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00378957

Quicke, D. L. (2015). The Braconid and Ichneumonid parasitoid wasps: Biology, Systematics, Evolution and Ecology. Metopiinae. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell.

Resh, V. H., & Cardé, R. T. (Eds.). (2009). Encyclopedia of insects. San Diego, CA: Academic press.

Roderick, G. K. (1996). Geographic structure of insect populations: gene flow, phylogeography, and their uses. Annual Review of Entomology, 41, 325–352. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.en.41.010196.001545

Rogers, A. R., & Harpending, H. (1992). Population growth makes waves in the distribution of pairwise genetic differences. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 9, 552–569. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040727

Rozas, J., Sánchez-DelBarrio, J. C., Messeguer, X., & Rozas, R. (2003). DnaSP, DNA polymorphism analyses by the coalescent and other methods. Bioinformatics, 19, 2496–2497. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btg359

Sánchez, J. A., Romero, J., Ramírez, S., Anaya, S., & Carrillo, J. L. (1998). Géneros de Braconidae del estado de Guanajuato (Insecta: Hymenoptera). Acta Zoológica Mexicana (nueva serie), 79, 59–137. https://doi.org/10.21829/azm.1998.74741721

Sarfraz, M., Dosdall, L. M., & Keddie, B. A. (2009). Host plant nutritional quality affects the performance of the parasitoid Diadegma insulare. Biological Control, 51, 34–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2009.07.004

Schoonhoven, L. M., Van Loon, J. J., & Dicke, M. (2005). Insect-plant biology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Seifert, C. L., Strutzenberger, P., & Fiedler, K. (2022). Ecological specialisation and range size determine intraspecific body size variation in a speciose clade of insect herbivores. Oikos, 2022, e09338. https://doi.org/10.1111/oik.09338

Singer, M. S., & Stireman III, J. O. (2005). The tri-trophic niche concept and adaptive radiation of phytophagous insects. Ecology Letters, 8, 1247–1255. https://doi.org/10.

1111/j.1461-0248.2005.00835.x

Stillwell, R. C., & Fox, C. W. (2007). Environmental effects on sexual size dimorphism of a seed-feeding beetle. Oecologia, 153, 273–280. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-007-0724-0

Stillwell, R. C., & Fox, C. W. (2009). Geographic variation in body size, sexual size dimorphism and fitness components of a seed beetle: local adaptation versus phenotypic plasticity. Oikos, 118, 703–712. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0706.2008.17327.x

StiremanIII, J. O., Nason, J. D., & Heard, S. B. (2005). Host-associated genetic differentiation in phytophagous insects: general phenomenon or isolated exceptions? Evidence from a goldenrod-insect community. Evolution, 59, 2573–2587. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0014-3820.2005.tb00970.x

Takabayashi, J., & Dicke, M. (1996). Plant-carnivore mutualism through herbivore-induced carnivore attractants. Trends

in plant science, 1, 109–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1360-

1385(96)90004-7

Tamura, K., Dudley, J., Nei, M., & Kumar, S. (2007). MEGA4: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 24, 1596–1599. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msm092

Turner, R. M., Bowers, J. E., & Brugess, T. L. (2022). Sonoran Desert plants: an ecological atlas. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Vilhelmsen, L., Isidoro, N., Romani, R., Basibuyuk, H. H., & Quicke, D. L. (2001). Host location and oviposition in a basal group of parasitic wasps: the subgenual organ, ovipositor apparatus and associated structures in the Orussidae (Hymenoptera, Insecta). Zoomorphology, 121, 63–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004350100046

Visser, M. E. (1994). The importance of being large: the relationship between size and fitness in females of the parasitoid Aphaereta minuta (Hymenoptera: Braconidae). Journal of Animal Ecology, 63, 963–978. https://doi.org/10.

2307/5273

Wonglersak, R., Fenberg, P. B., Langdon, P. G., Brooks, S. J., & Price, B. W. (2020). Temperature-body size responses in insects: a case study of British Odonata. Ecological Entomology, 45, 795–805. https://doi.org/10.1111/een.12853

Diversity of anurans and use of microhabitatsin three vegetation coverages of the Santuario de Flora y Fauna Los Colorados, Colombian Caribbean

Omer José Jiménez-Ortega a, d, Keiner L. Tílvez b, Joselin Castro-Palacios a,

Andrés García c, *, Gabriel R. Navas a, Julio Abad Ferrer-Sotelo e, Dilia Naranjo-Calderón e, Juan Gabriel Díaz-Castellar e, Víctor Buelvas-Meléndez e

a Universidad de Cartagena, Campus San Pablo, Grupo de Investigación en Hidrobiología, Programa de Biología, Carrera 50#24-120, Zaragocilla, Cartagena de Indias, Colombia.

b Universidad de Cartagena, Campus San Pablo, Grupo de Investigación en Biología Descriptiva y Aplicada, Carrera 50#24-120, Zaragocilla, Cartagena de Indias, Colombia

c Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Biología, Estación de Biología Chamela, Apartado postal 21, 48980 San Patricio, Jalisco, México

d Parque Temático Vivarium del Caribe-Fundación Archosauria zona norte km 15, Provincia de Cartagena, Bolívar, Colombia

e Santuario de Flora y Fauna Los Colorados, Parques Nacionales Naturales de Colombia, Carrera 8# 9-20 Plaza Olaya Herrera, San Juan Nepomuceno, Bolívar, Colombia

*Corresponding author: chanoc@ib.unam.mx (A. García)

Received: 28 October 2023; accepted: 18 March 2024

Abstract

This study aimed to determine anuran diversity and the use of microhabitats in 3 vegetation covers in the Santuario de Flora y Fauna Los Colorados. Five field trips of 6 days each were made, 2 days and 2 nights in each cover: forest, pasture, and crop. Sampling was carried out with the visual encounter inspection technique under a randomized design by random walks with manual capture. A total of 19 species were recorded, 14 in the forest, 13 in pasture, and 12 in crop. Pasture and crop were the vegetation covers with the greatest similarity of species. This work updates the list of anuran species recorded in the management plan of the Santuario de Flora y Fauna Los Colorados 2018-2023. The greatest number of anuran species was associated with leaf litter, “jagüeyes”, and soils. The transformation of the landscape as a result of agriculture and cattle ranching generated changes in the richness, abundance, composition, and use of microhabitats of the anurans present in the Santuario de Flora y Fauna Los Colorados.

Keywords: Landscape transformation; Vegetation coverage; Microhabitat; Tropical dry forest

Diversidad de anuros y uso de microhábitats en tres coberturas vegetales del Santuario de Flora y Fauna Los Colorados, Caribe colombiano

Resumen

Este estudio tuvo como objetivo determinar la diversidad de anuros y el uso de microhábitats en 3 coberturas vegetales en el Santuario de Flora y Fauna Los Colorados. Se hicieron 5 salidas de campo de 6 días cada una, 2 días y 2 noches en cada una: bosque, potrero y cultivo. Se realizaron muestreos con la técnica de inspección por encuentro visual, bajo el diseño aleatorizado por caminatas al azar con captura manual. Se registraron 19 especies, 14 de ellas en bosque, 13 en potrero y 12 en cultivo, siendo el potrero y el cultivo las coberturas con mayor similitud de especies. Este trabajo actualiza el listado de las especies de anuros registrados en el Plan de manejo del Santuario de Flora y Fauna Los Colorados 2018-2023. El mayor número de especies de anuros se encontró asociado a la hojarasca, el jagüey y los suelos. La transformación del paisaje producto de la agricultura y la ganadería genera cambios en la riqueza, abundancia, composición y uso de microhábitats de los anuros presentes en el Santuario de Flora y Fauna Los Colorados.

Palabras clave: Transformación del paisaje; Coberturas vegetales; Microhábitat; Bosque seco tropical

© 2024 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Biología. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/)

Introduction

Seasonally tropical dry forests (STDF here after) in Colombia are distributed mainly in the inter-Andean valleys and the Caribbean region (García et al., 2014), the latter being one of the regions with the best conserved areas of this ecosystem (Pizano et al., 2014; Rodríguez et al., 2012). However, Etter et al. (2008) point out that indiscriminate deforestation for various anthropogenic activities such as agriculture and livestock have generated large reductions in forest cover over time. This, combined with other activities such as mining and urban development (Cristal et al., 2020; Galván-Guevara et al., 2015; Jiménez et al., 2018), cause biological and ecological interactions to deteriorate, and the functionality of the ecosystem is compromised (Thomson et al., 2017), which is why Colombian STDFs have been classified as critically endangered (CR) (Etter et al., 2017). Consequently, it is a strategic ecosystem for conservation study due to its high risk of disappearing, strongly threatening the local fauna and the people who depend directly and indirectly on the ecosystem services it provides (Andrade, 2011).

One of most sensitive groups to forest transformation is amphibians, including anurans, which are highly dependent on humid places or sites with high water availability since most of their species have indirect development, permeable skin, and anamniote-type eggs (O’Malley, 2007). The spatial distribution and microhabitats use by anurans depend on the physiological requirements of each organism, and the available resources (Urbina-Cardona et al., 2006; Zug et al., 2009), as suggested by several studies showing many anuran species prefer forested areas (Cáceres-Andrade & Urbina-Cardona, 2009; García-R et al., 2005; Román-Palacios et al., 2016). Consequently, these species may be affected by anthropogenic disturbance, forest fragmentation, and loss (Cáceres-Andrade & Urbina-Cardona, 2009).

Forest transformation is among the main factors affecting anuran communities (Cáceres-Andrade & Urbina-Cardona, 2009; Marín et al., 2017; Romero, 2013; Vargas & Bolaños-L, 1999), causing around 38% of Colombian amphibians to be included under a category of endangered species and positioning Colombia as the country with the highest number of threatened species according to the second global review of amphibians (Re:wild, 2023). A study carried out by Duarte-Marín et al. (2018) in 3 habitats of the Selva de Florencia National Natural Park estimated that the covers with greater vegetation (forest and pine forest) presented greater richness and diversity of anurans than those covers with less vegetal complexity (pastures). This means land use and changes in vegetation cover are factors that influence amphibian species richness and diversity. Therefore, species that are not adapted to the new environmental conditions created by landscape transformation are eliminated from the assembly, negatively affecting the ecosystem processes in which they had intervention (Díaz et al., 2006).

Additionally, forest fragmentation has created barriers that prevent anuran dispersal, resulting in a decrease in their genetic diversity (De Sá, 2005). Furthermore, it has generated changes in the composition and abundance of anurans to an extent that depends on the levels of disturbance (Acuña-Vargas, 2016), with an increase in the penetration of light and winds along the perimeter of a forest remnants, coming from non-forest environments such as pastures, with the subsequent changes in microclimates (Echeverry et al., 2006; Galván-Guevara et al., 2015; Laurence & Gascon, 1997), phenomena known as the edge effect ( Rojas & Pérez-Peña, 2018). However, studies such as Blanco and Bonilla (2010) show that some transformed areas provide a greater number of microenvironments due to the modifications made by humans (e.g., creation of jagüeyes) and record greater richness and abundance of anurans species when compared to less transformed areas, which is known as intermediate disturbance theory (Conell, 1978). However, it must be considered that the species found in these areas have extensive plasticity to tolerate the environmental and structural gradients generated by anthropogenic disturbance, that is, they are resilient (Cáceres-Andrade & Urbina-Cardona, 2009).

Based on the above, the general objective of this research was to determine the diversity of anurans and their use of microhabitats in 3 vegetation covers within the Los Colorados Flora and Fauna Sanctuary (SFF Los Colorados), an important protected area in the Caribbean region of Colombia, which contributes to the understanding of how amphibians respond to changes in land use for agriculture and livestock, in order to provide information that can be useful for environmental entities to determine management and conservation policies for these organisms in landscape fragments.

The specific objectives are: 1) to determine the richness, abundance, diversity, and composition of anurans in 3 vegetation covers that are representative of the Los Colorados SFF; 2) to describe the use of the microhabitat by the species in each vegetation cover; 3) to analyze and compare the relationship between precipitation and environmental temperature with the richness, abundance, and diversity of species in each vegetation cover and; 4) to analyze and compare the alpha and beta diversity of anuran species in each vegetation cover.

We expect to record differences between the 3 types of vegetation cover, hypothesizing that due to the greater heterogeneity of an ecosystem in better conservation condition such as the tropical forest, it will register a greater richness and diversity of species and its species composition will differ with respect to the other covers. While the use of the microhabitat by the species will differ in each cover and will depend on the variety of natural or anthropogenic substrates existing in each site.

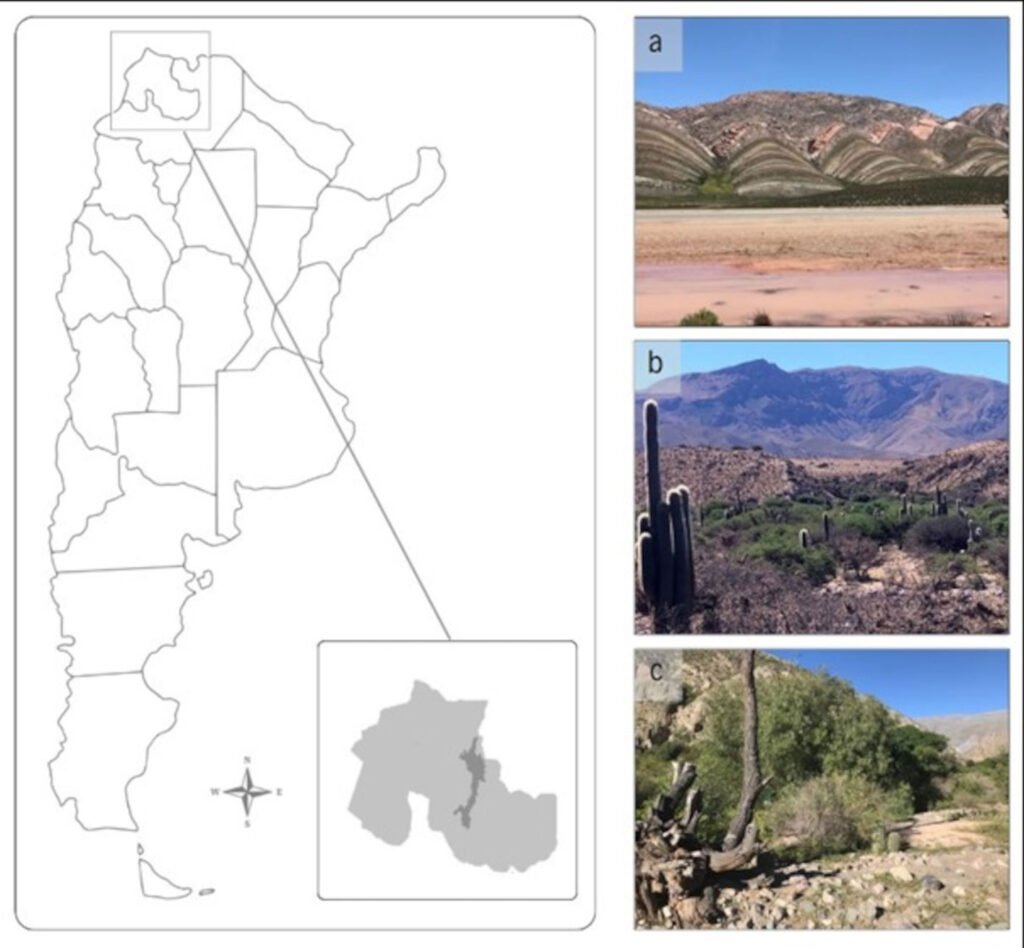

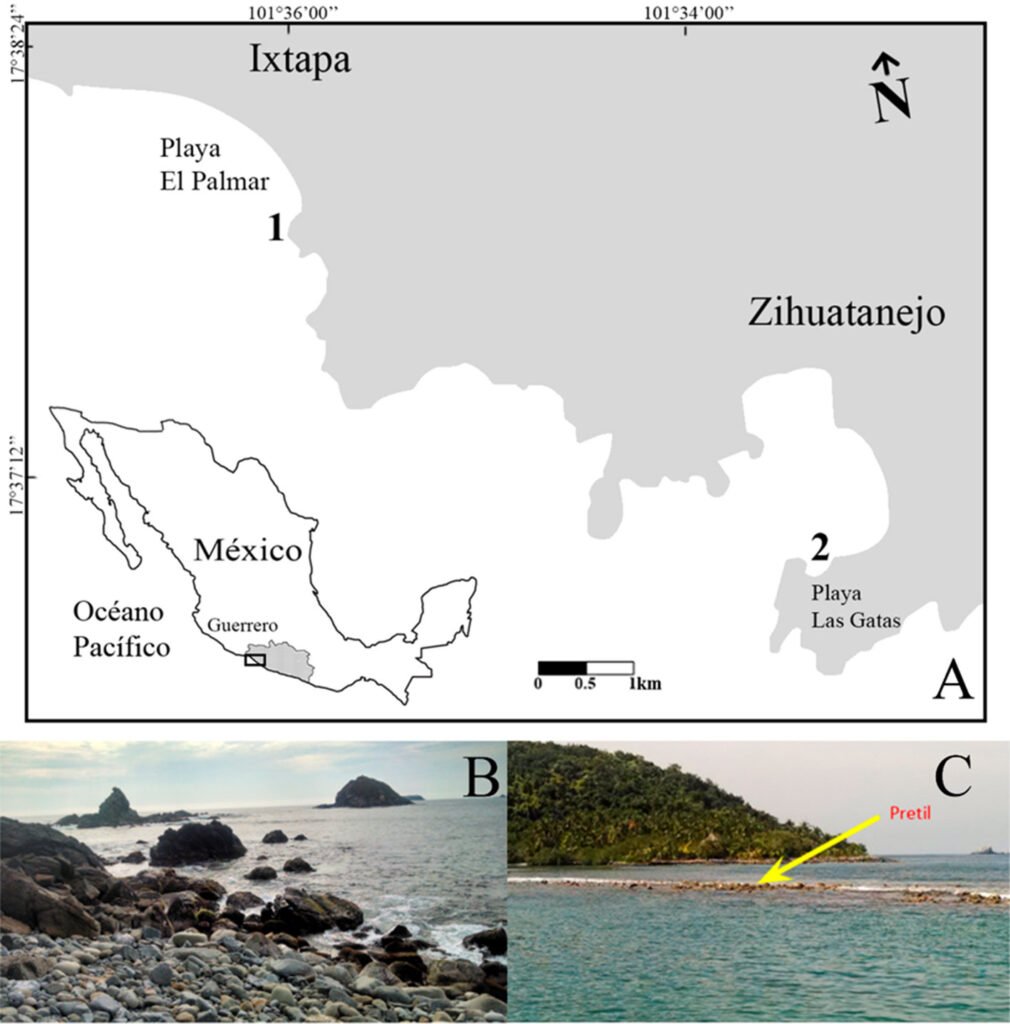

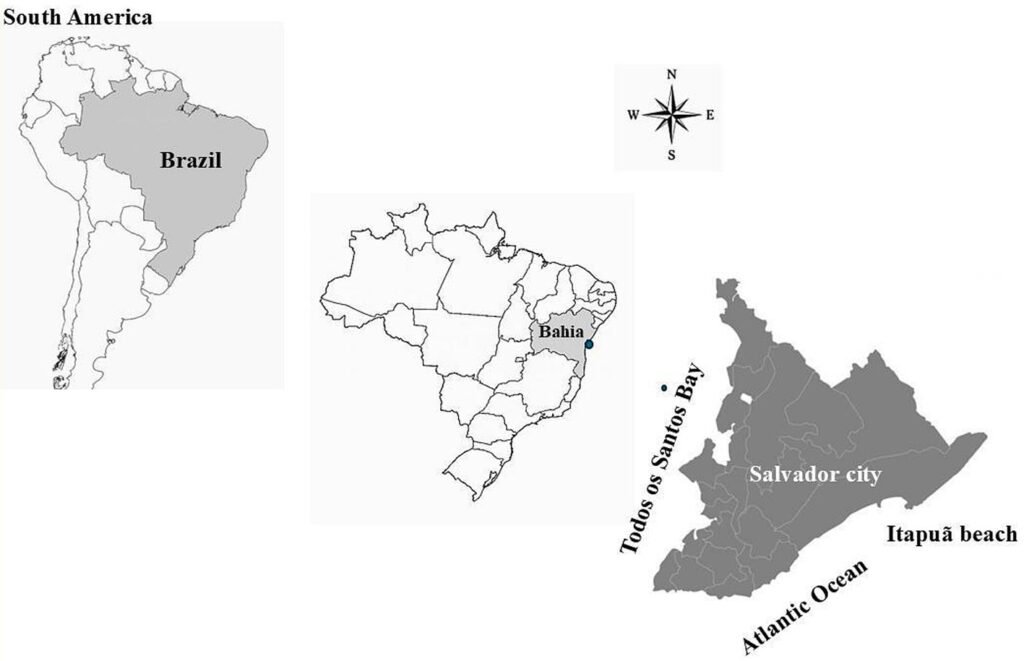

Materials and methods

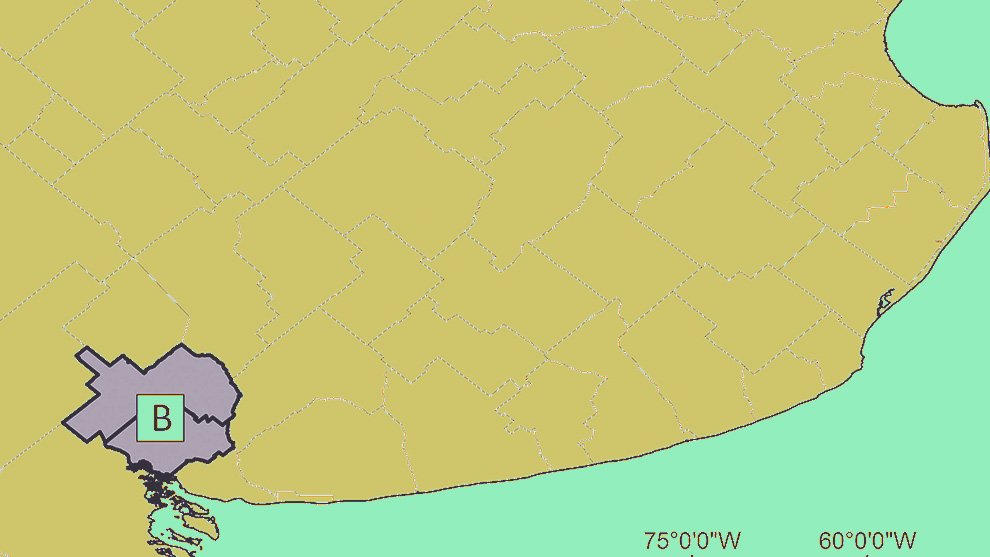

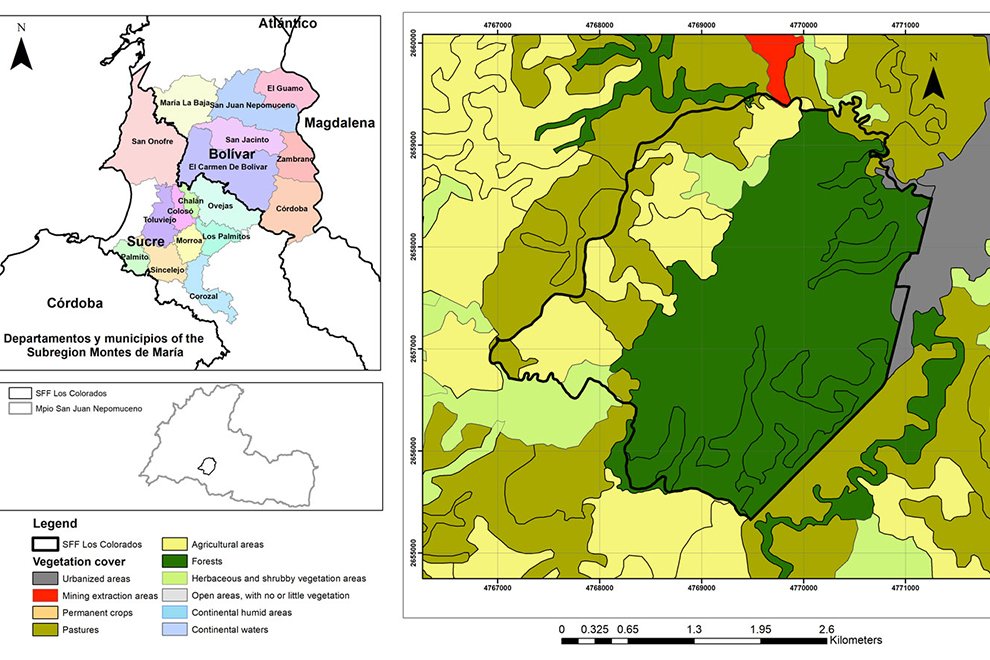

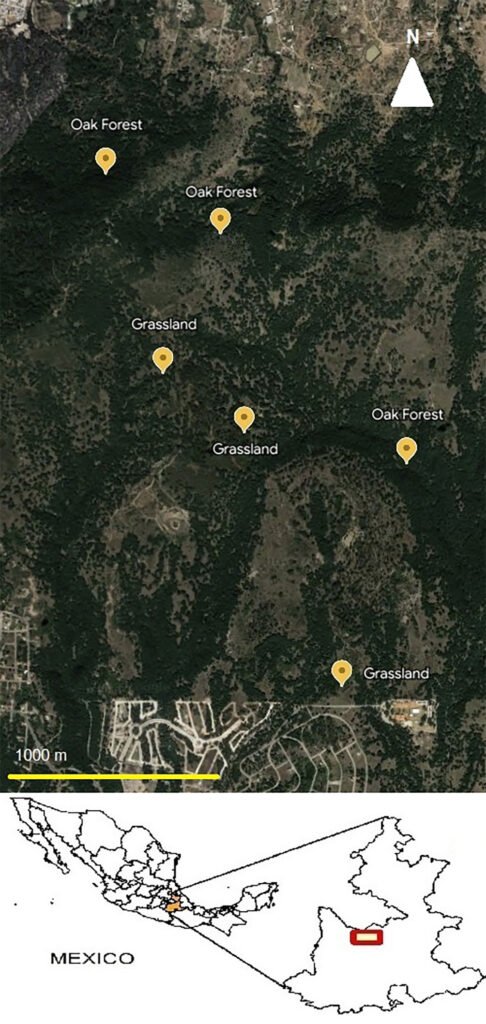

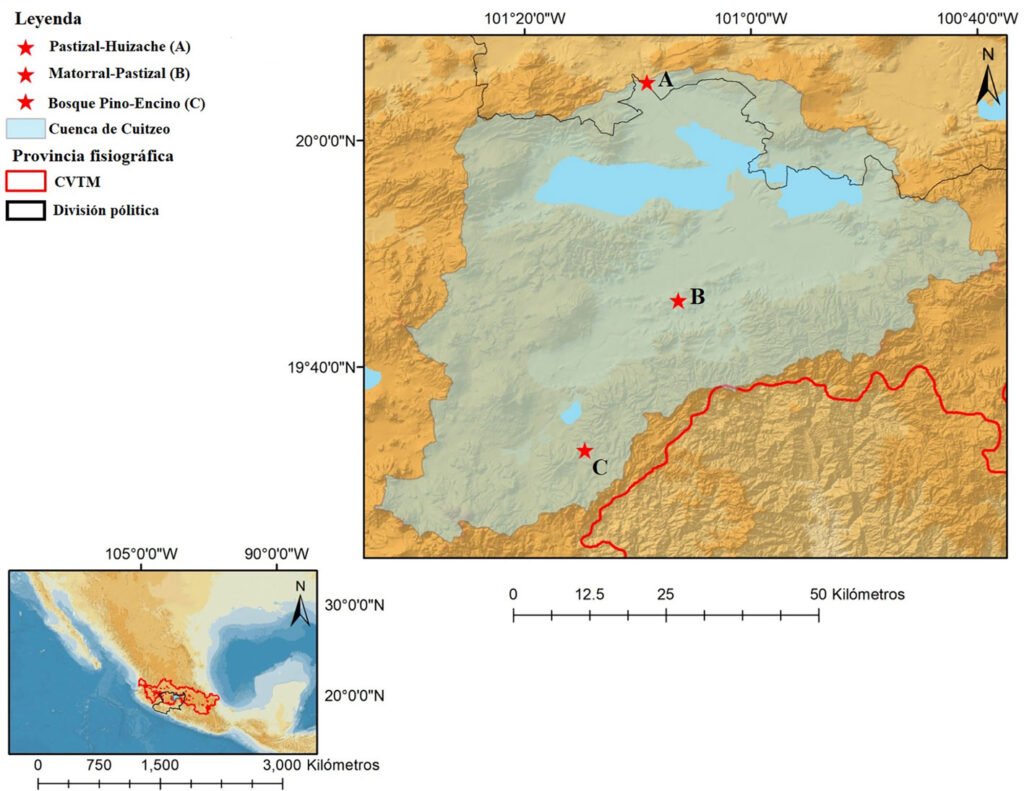

Montes de María is a subregion of the Colombian Caribbean. It is located between the departments of Sucre and Bolívar with an area of 6,297 km2, of which 3,719 km2 belong to the department of Bolívar (Aguilera-Díaz, 2013; Herazo et al., 2017). It integrates several municipalities, among which is San Juan Nepomuceno, where the SFF Los Colorados is located at 9°56’06.7” N, 75°06’48.7” W (Fig. 1) with an area of 1,041.96 ha, an average high temperature of 28 °C and an elevation of 23 m asl (Jiménez et al., 2018). Due to the seasonality of rainfall in the region, 3 seasons can be identified, each lasting 4 months and including the dry season (December to April), the transition season (little rain, May to August), and the rainy season (abundant rain, September to November). The average precipitation is around 1,643mm with a monthly average of 137mm (Rangel & Carvajal-Cogollo, 2012).

SFF Los Colorados is composed of a small mountain system formed by sedimentary rocks, in which the largest and most important STDF relic of Montes de María is located (Jiménez et al., 2018). This ecosystem has humid forest components, which is why it is considered a place of high species diversity (IAVH, 1998). Its hydrographic system is made up of 2 streams: Cacaos and Salvador, located on the south and north sides, respectively; it also has a large number of ravines that flow into these streams (Jiménez et al., 2018). There are 6 land uses within the SFF Los Colorados (Fig. 1), which are in descending order by their percentage of coverage, forest (66.36%), agricultural areas (17.29%), pastures (12.01%), herbaceous and shrubby vegetation areas (3.51%), urbanized areas (0.80%), and mining extraction areas (0.02%). The exact age of the crop areas is unknown; this area has historically been agricultural, even before 1977 when the SFF Los Colorados was declared as a protected natural area. However, for about 10 years these areas have been in the succession stage towards shrublands because they were purchased and practically little cultivated. There are only crops at the sampling point where yam (Dioscorea) or tuber is grown. The only management that is done with these crops is slash-and-burn. With respect to livestock, none of the pasture areas in the sampling sites have more than 40 heads of livestock. No fertilizers or other types of agrochemicals or pesticides are used.

SFF Los Colorados faces 2 main problems in the conservation of their natural environments. The first is an occupancy rate close to 30% of its surface (3 neighborhoods and 11 properties). The second is the inadequate environmental planning outside the protected area that has generated a transformation of the landscape because of cattle ranching, agriculture, forest plantations, mining activities, the presence of a national highway as a limit, and the proximity to a municipal seat of 25,000 inhabitants (Jiménez et al., 2018).

A two-day prospecting visit was carried out at the SFF Los Colorados in November 2021 to inspect the site and locate the sampling points. Subsequently, 5 field trips of 6 days each were carried out (2 days and 2 nights in each cover: forest, pasture, and crop) during the months of January, February, March, April, and June 2022. In this way, sampling was carried out during the dry and transition season, that is, under conditions of no rain (February to April) or very little rain (June). In these months 2 researchers and 2 officials from the SFF Los Colorados carried out daytime (8:00 -10:00 am) and nighttime (6:00-8:00 pm) outings with a constant speed route, for a sampling effort of 160 man-hours in each coverage for a total of 480 man-hours.

The visual encounter inspection technique was used to locate and record anuran species and their abundance, under the randomized design of random walks (Crump & Scott, 2001) and manual capture of individuals (Aguirre-León, 2011; Manzanilla & Péfaur, 2000). The identification of anuran species in each cover (forest, pasture, and crop) was based on regional taxonomic keys (Ballesteros-Correa et al., 2019; Cuentas et al., 2002; Dunn, 1994), supported by field guides with photographs (Meza-Tílvez et al., 2018; Salvador & Gómez-Sánchez, 2018), and databases (Acosta-Galvis, 2021).

The 3 selected coverages were described following the CORINE Land Cover methodology adapted for Colombia (IDEAM et al., 2008) as follows: forest is an area made up mainly of tree elements of native or exotic species, trees being woody plants with a single main trunk or in some cases with several stems, which also have a defined and semi continuous canopy. In the study area, trees reach a height greater than 5m, and watercourses with a width of less than 50m were found. Pasture includes lowlands covered with grasses and some scattered trees with a height greater than 5 m, which are located on hills and flat pastures in warm climates. Crops are areas dedicated primarily to the production of food, fiber, and other raw materials with permanent, transitional, or annual crops of avocado, chili and cassava. Temporary yam crops are mainly found in the study area.

To describe microhabitat used by anurans, the number of individuals of each species observed in one of the substrate types (leaf litter, branch, trunk, sites with the presence of water, rock, soil, herbaceous or shrubby vegetation) were recorded (Cáceres-Andrade & Urbina-Cardona, 2009).

Figure 1. Location of the Los Colorados Flora and Fauna Sanctuary; source National Natural Parks of Colombia, with permission granted by SFF Los Colorados.

All observed species were photographed and at least 1 individual per species was collected, anesthetized with 2% xylocaine gel on the head and belly, and sacrificed (McDiarmid, 1994). To avoid tissue necrosis, they were prepared and fixed with 10% formalin (McDiarmid, 1994; Simmons & Muñoz-Saba, 2005), then placed in a suitable position in a container that had a white absorbent paper impregnated with 10% formalin. Distinctive characteristics were then observed. Finally, they were preserved in 70% ethanol (Cortez-F et al., 2006). The collected material was deposited in the Armando Dugand Gnecco collection of the Universidad del Atlántico, with the following catalog numbers: UARC-Am-00508, UARC-Am-00509, UARC-Am-00510, UARC-Am-00511, UARC- Am-00512, UARC-Am-00513, and UARC-Am-00514. The collecting permit was granted by the regional environmental authority called the Regional Autonomous Corporation of the Canal del Dique (Cardique), and the permit number is the resolution number 0751 of June 27, 2014. In addition, through the research endorsement approved by National Parks of Colombia, No. 20212000004933, October 25, 2021.

Information on the number of species and their abundance in each cover and climatic season was stored in an Excel. To confirm sampling was carried out on dates with the typical characteristics of the climatic seasons (rainy and dry), we graphed and compared statistically (ANOVA) the average precipitation and temperature for the months in which the sampling was carried out based on data obtained from the Institute of Hydrology, Meteorology and Environmental Studies (IDEAM) of the Guamo-Bolívar Station (Retrieved on July 19, 2022, from: http://www.ideam.gov.co/web/atencion-y-participacion-ciudadana/pqrs).

To detect significant differences in alpha diversity (richness, abundance, Simpson, Shannon), the Kruskall-Wallis or ANOVA tests were applied, depending on the normality of the data using the Shapiro-Wilk test and homogeneity of variances using Levene’s test (p < 0.05).

Alpha diversity was determined as the species richness for each coverage (Moreno, 2001), and was evaluated using Chao 1, 2, and Jack 1 estimators in EstimateS v. 9.1 (Villareal et al., 2004). In addition, bootstrap was used, which is useful to determine richness with a high number of rare species (Colwell & Coddington, 1994; Magurran, 2004). On the other hand, the diversity of anurans was estimated for each cover using the Shannon-Wiener index in the program PAST v. 4.03 (Hammer et al., 2001), and dominance using the Simpson index, where values close to 0 were considered as low levels of dominance and those close to 1 as high levels of dominance (Clarke et al., 2014).

To evaluate the turnover of anuran species between different covers (forest, pasture, and crops), the Jaccard index was used because it relates the number of shared species to the total number of exclusive species (Villareal et al., 2004). The range of values goes from 0 in the case of no shared species, to 1 when the covers have the same species composition (Moreno, 2001). From the estimator, a dendrogram was constructed in PAST v. 4.03.

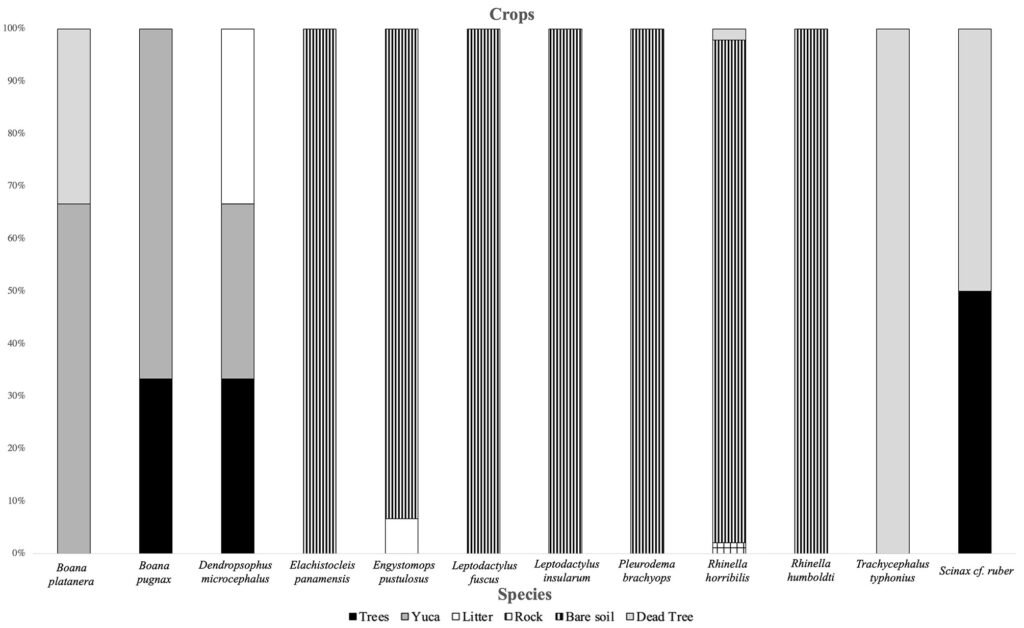

To analyze the use of microhabitats, a graph was constructed where the percentage of use of each microhabitat by species and cover was established, to observe in each cover which microhabitats were most used by each species of anuran. Data were plotted in Excel.

Results

In total 1,269 individuals belonging to 19 species and 1 casual record (not included in this analysis) were recorded and grouped into 13 genera and 7 families (Table 1). Hylidae and Leptodactylidae were the families with the greatest species recorded, 8 and 6, respectively whereas only 1 species was recorded for Microhylidae and Phyllomedusidae.

Table 1

Taxonomic list and number of anuran individuals recorded in forest, crop, and pasture cover in the Los Colorados Flora and Fauna Sanctuary.

| Family | Species | Forest | Crops | Pasture |

| Bufonidae | Rhinella horribilis (Wiegmann, 1833) | 29 | 48 | 89 |

| Rhinella humboldti (Spix, 1824) | 2 | 97 | 101 | |

| Ceratophryidae | Ceratophrys calcarata (Boulenger, 1890)* | |||

| Dendrobatidae | Dendrobates truncatus (Cope, 1861, “1860”) | 173 | ||

| Hylidae | Boana platanera (Escalona et al., 2021) | 23 | 3 | 4 |

| Boana pugnax (Schmidt, 1857) | 3 | 90 | ||

| Dendropsophus ebraccatus (Cope, 1874) | 1 | |||

| Dendropsophus microcephalus (Cope, 1886) | 2 | 4 | 59 | |

| Scarthyla vigilans (Solano, 1971) | 3 | |||

| Scinax cf. rostratus (Peters, 1863) | 5 | 14 | ||

| Scinax cf. ruber (Laurenti, 1768) | 1 | 2 | ||

| Trachycephalus typhonius (Linnaeus, 1978) | 6 | 1 | 7 | |

| Leptodactylidae | Engystomops pustulosus (Cope, 1864) | 190 | 15 | 12 |

| Leptodactylus fuscus (Schneider, 1799) | 2 | 55 | ||

| Leptodactylus insularum (Barbour, 1906) | 12 | 1 | 81 | |

| Leptodactylus poecilochilus (Cope, 1862) | 44 | |||

| Leptodactylus savagei (Heyer, 2005) | 17 | |||

| Pleurodema brachyops (Cope, 1869, “1868”) | 38 | 10 | ||

| Microhylidae | Elachistocleis panamensis (Dunn et al., 1948) | 19 | ||

| Phyllomedusidae | Phyllomedusa venusta (Duellman & Trueb, 1967) | 1 | 5 | |

| * Species recorded casually outside the sampled coverage, which is not included in the analyses of our study. |

Table 2

Richness estimators and percentages of representativeness with respect to the number of anuran species recorded in the 3 coverages of the SFF Los Colorados.

| Richness estimator | Cover | ||

| Forest | Pasture | Crops | |

| Species recorded | 14 | 13 | 12 |

| Chao 1 | 15.00 (86.7%) | 13.00 (100.0%) | 12.33 (97.3%) |

| Chao 2 | 14.68 (88.6%) | 13.00 (100.0%) | 12.90 (93.0%) |

| Jack 1 | 16.70 (77.8%) | 13.90 (93.5%) | 14.70 (81.6%) |

| Bootstrap | 15.40 (84.3%) | 13.57 (95.8%) | 13.32 (90.1%) |

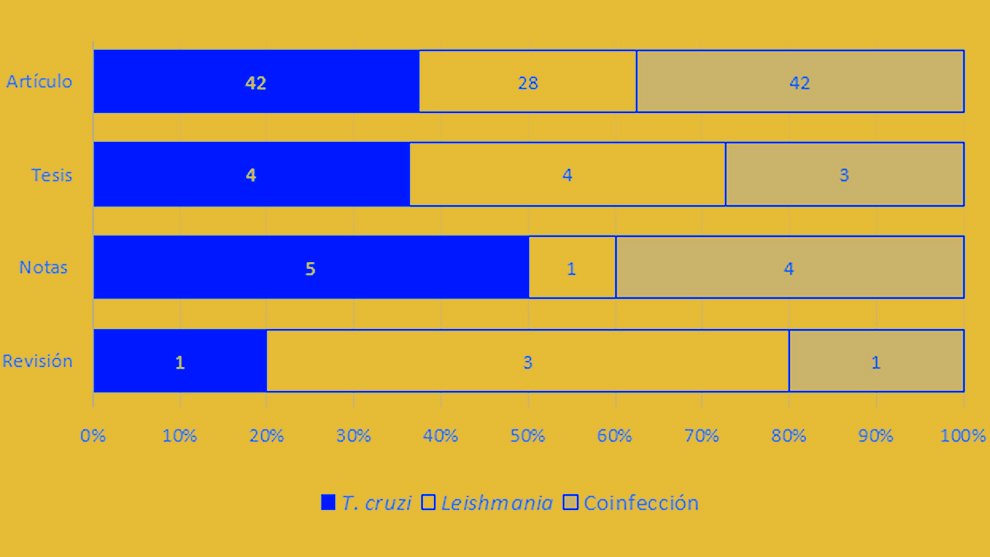

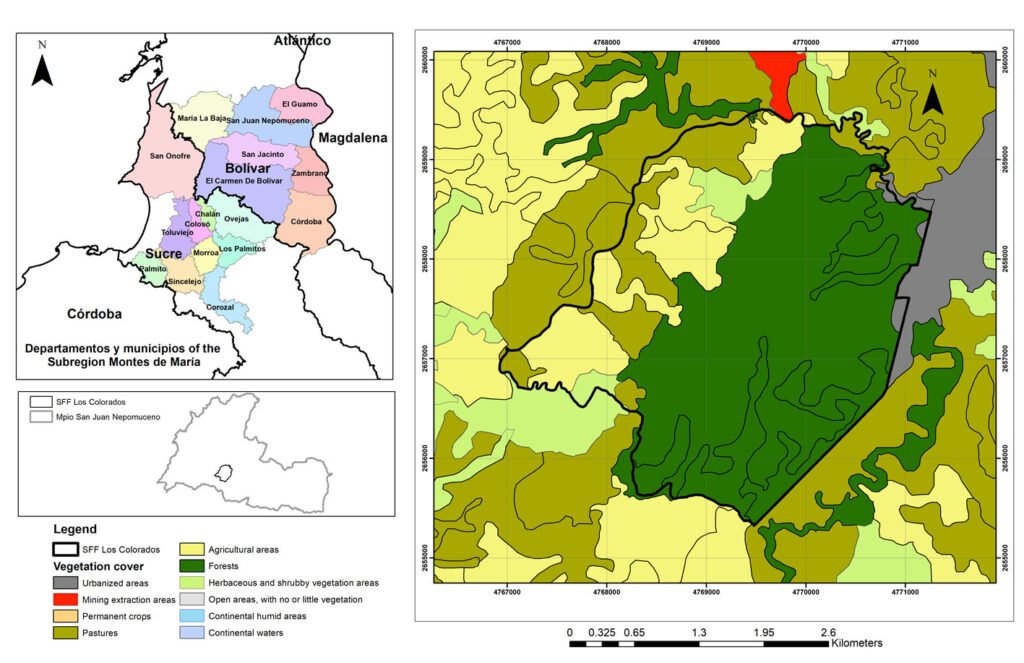

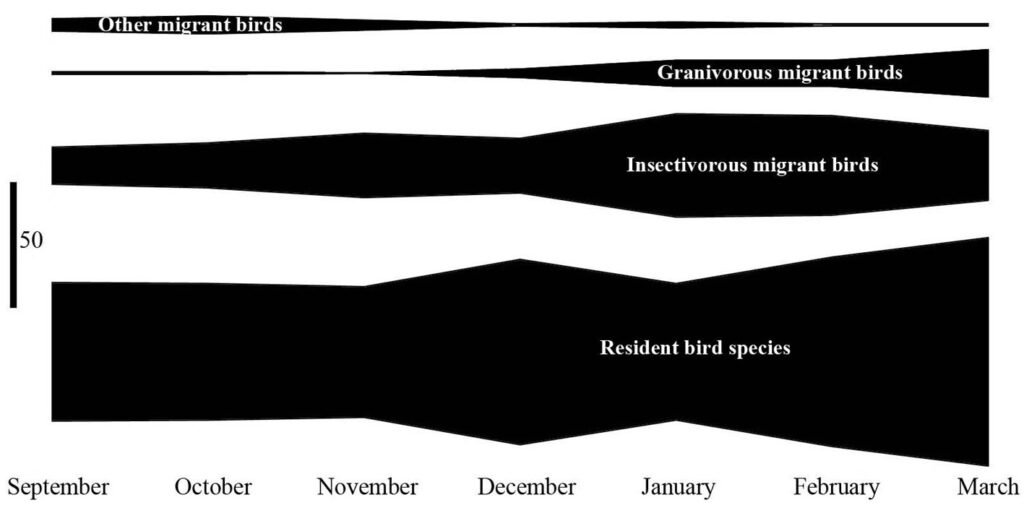

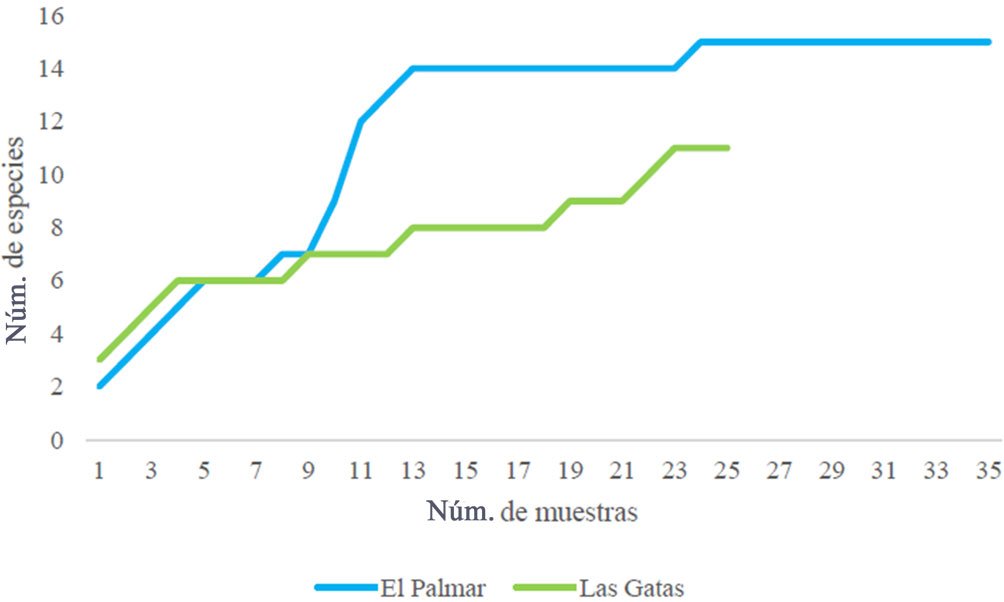

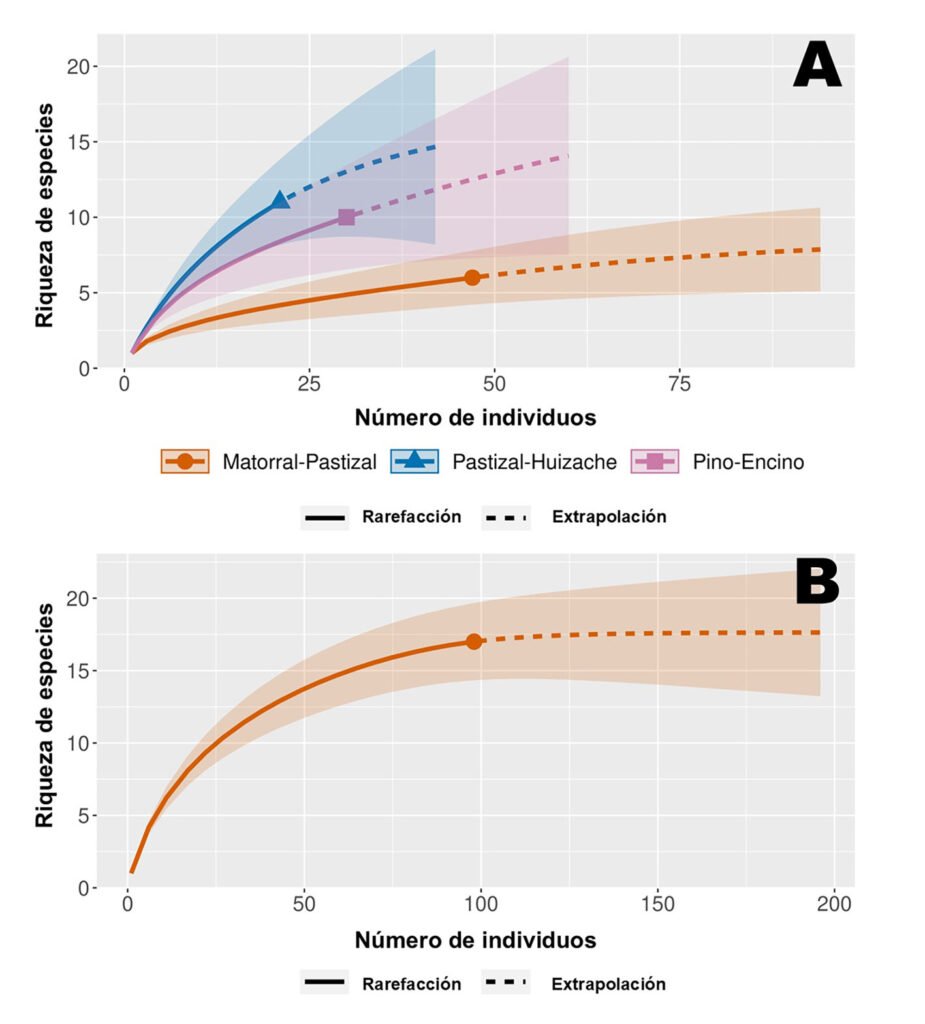

Alpha diversity was highest in forest (14 species), followed by pasture (13 species) and crop (12 species). The species accumulation curves in the 3 coverages based on the Chao 1, Chao 2, and bootstrap estimators allowed estimating a number of species similar to that recorded in the field and an efficiency in the sampling carried out with a representativeness greater than 80%. The Jack 1 estimator for forest indicates a representativeness of 77.8%, and for pasture and crops greater than 80% (Table 2, Fig. 2). In the singleton and doubleton curves (Fig. 2), a decreasing behavior is observed for the pasture and crop covers, indicating little probability of finding new anuran species in these covers. For forest, the doubleton curve shows an ascending behavior, indicating a probability of finding more species in this cover.

Figure 2. Accumulation curves of anuran species for the 3 coverages of the Los Colorados Flora and Fauna Sanctuary.

Figure 3. Box plots of richness (A), abundance (B), Shannon Index (C), and Simpson (D) for each of the 3 vegetation covers.

Figure 4. Histogram and box plot of daily ambient temperature across the sampling months; temperature (A, B), rainfall (C).

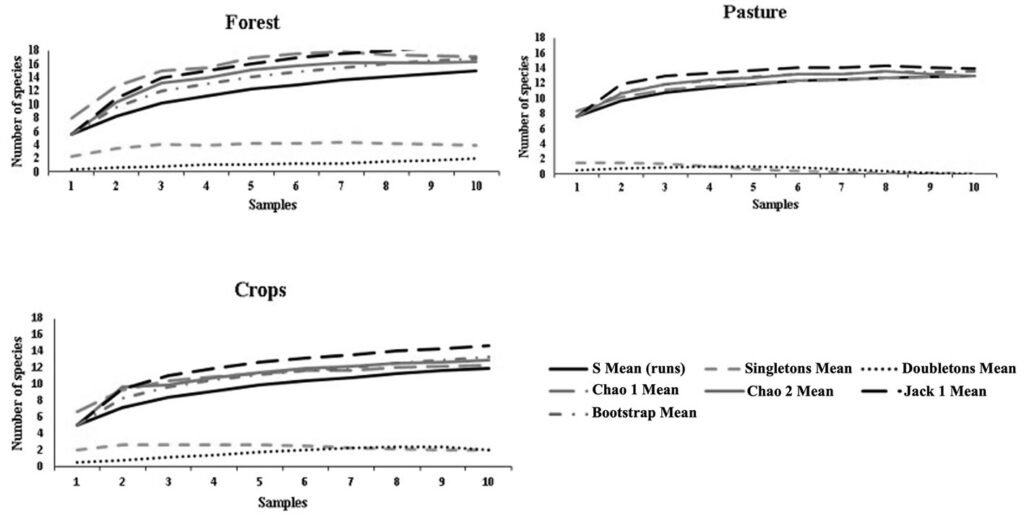

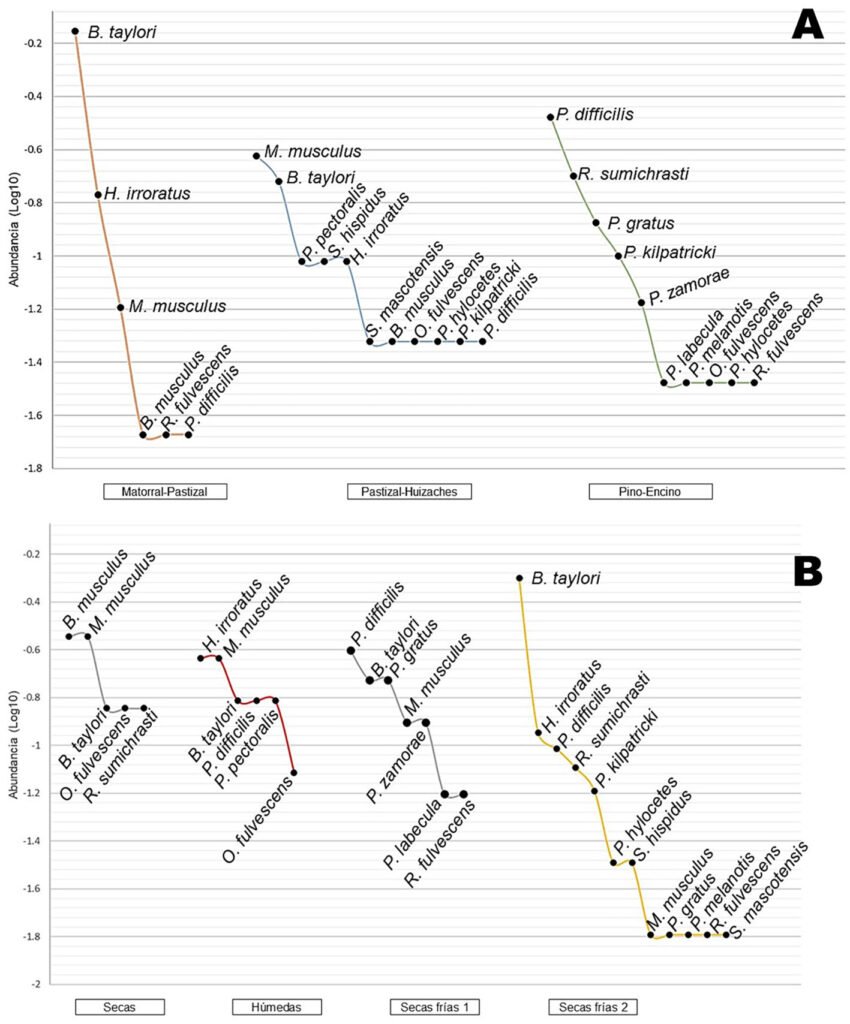

According to the determined Shannon-Wiener index, the diversity for forest cover was 1,631, crops 1,677, and pasture 2,107. On the other hand, Simpson’s index estimated a dominance of 0.726 for the forest, crops 0.746, and pasture 0.858. When comparing the metrics recorded in each vegetation cover (Fig. 3), the pastures registered on average the greatest richness, abundance, and diversity. The average richness was similar between the crops and the forest; however, the variation was greater in the crops. In contrast, the average and variation of abundance was greater in the forest than in the crops. The average species diversity was lowest in forests, intermediate in crops, and highest in pastures. There were statically differences of all metrics among vegetation cover; richness (one-way ANOVA, F = 5.456, df = 2, p > 0.05), abundance (H(χ2) = 4.63, p > 0.05), Shannon (one-way ANOVA, F = 16.71, df = 2, p > 0.05), and Simpson (H(χ2) = 15.97, p > 0.05).

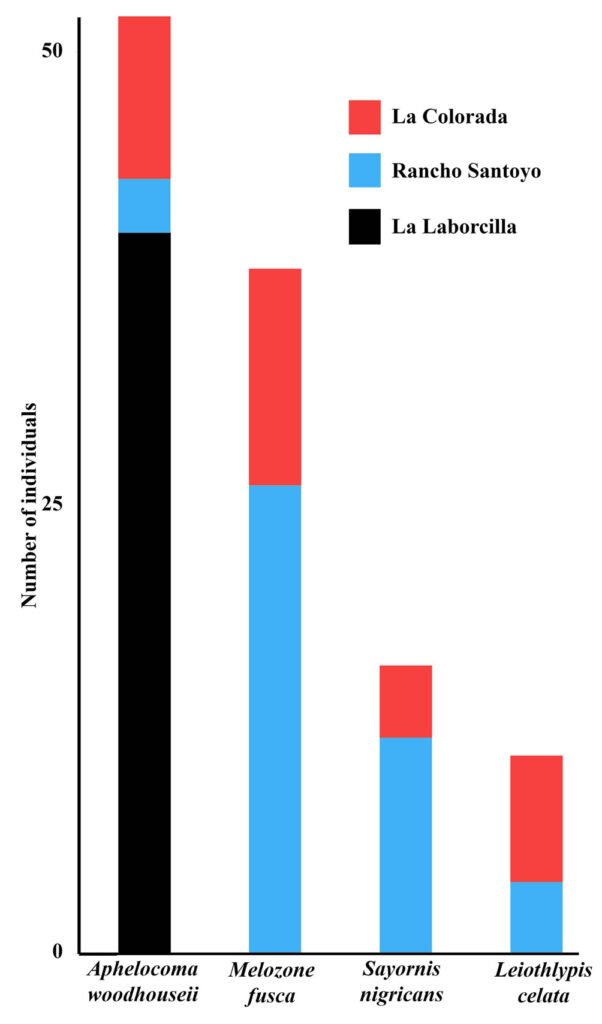

When we graph the monthly fluctuations of ambient temperature and precipitation (Fig. 4), it is evident that during the days and months of sampling, precipitation was little or none (monthly average from 1.3 mm in January to 7.4 mm in April) whereas monthly average temperature tended to increase from 21.5 °C to 23.3 °C from January to March and from 24.0 to 24.5 °C from April to June. These daily temperature records showed significant monthly differences (ANOVA, F = 67.1, df5 = 5, df2 = 79.8, p < 0.001). There were no significant monthly fluctuations with respect to precipitation (ANOVA, F = 1.78, df5 = 5, df2 = 78.8, p > 0.05). The species richness tended to be higher in April and June in all 3 vegetation covers (Fig. 5) whereas abundance was higher in the forest in March and higher for pastures and crops during April and June. Species diversity (Shannon and Simpson) in the forest was higher in March whereas in both crops and pastures it was higher in June (Fig. 5).

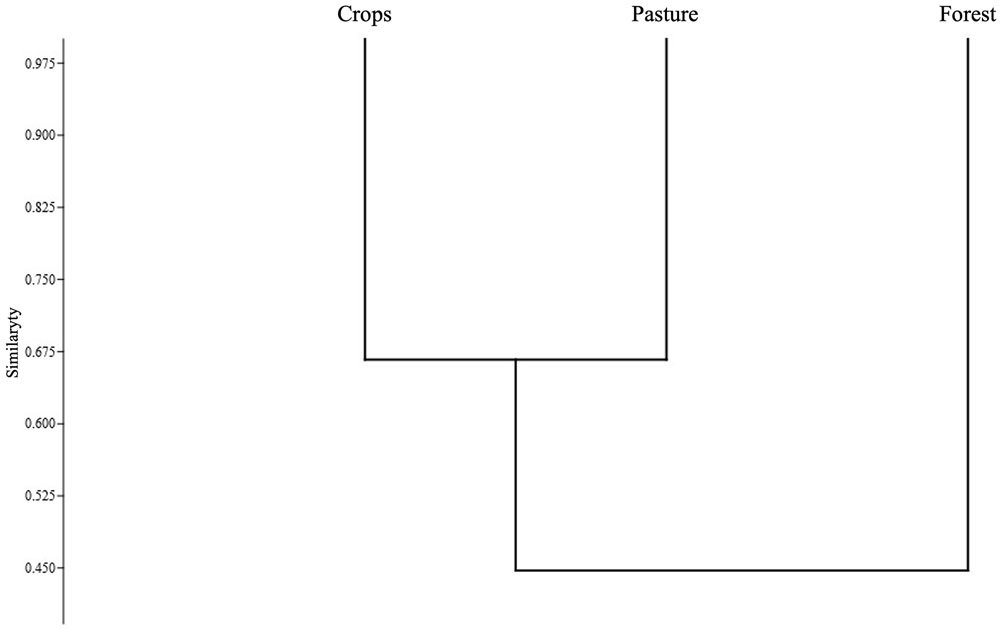

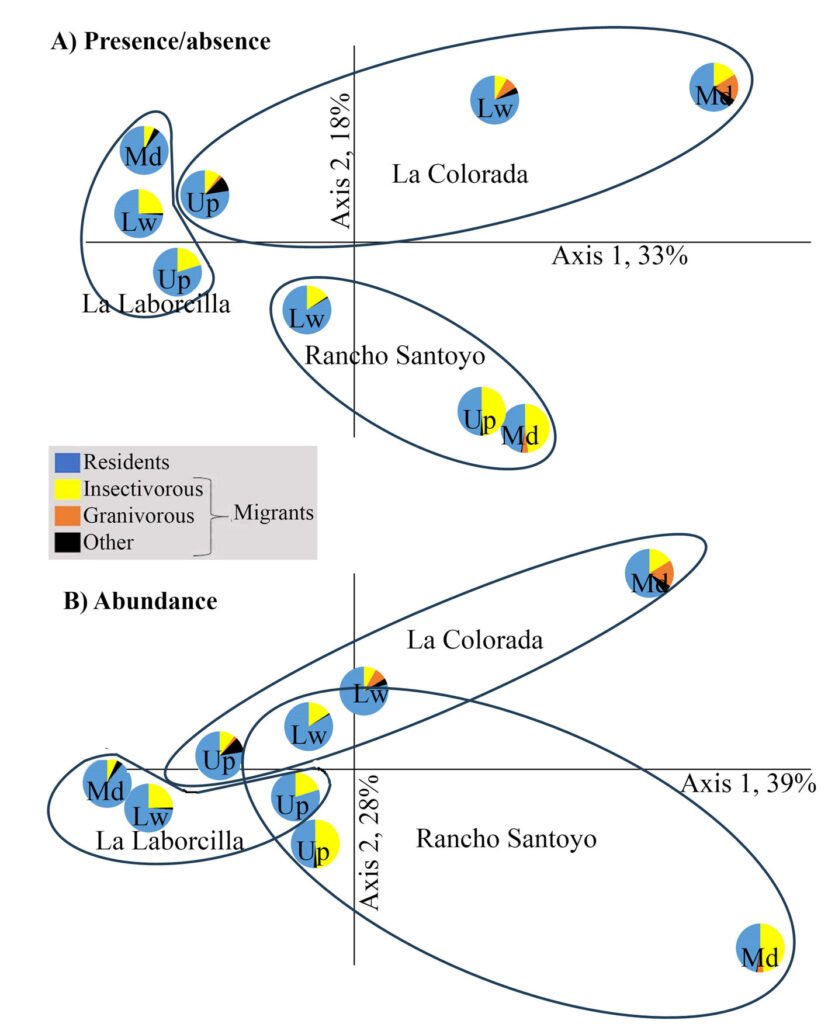

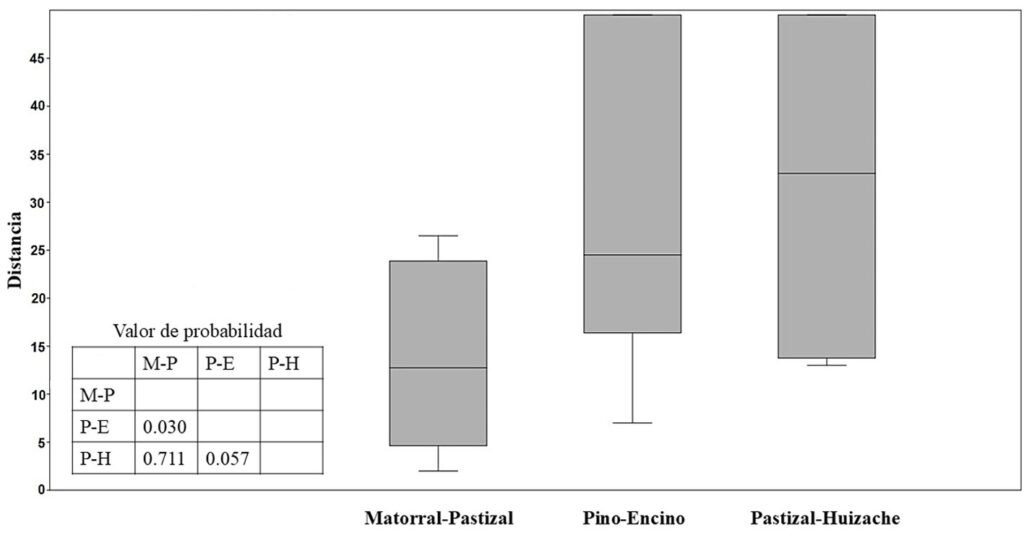

Based on the Jaccard similarity index, crop and pastures presented a greater degree of similarity (Fig. 6), that is, a greater number of shared species. The forest presented the greatest dissimilarity in species composition with respect to the crop and the pasture, having a greater number of unique species (D. truncatus, D. ebraccatus, L. poecilochilus, and L. savagei), which are shown in Table 1.

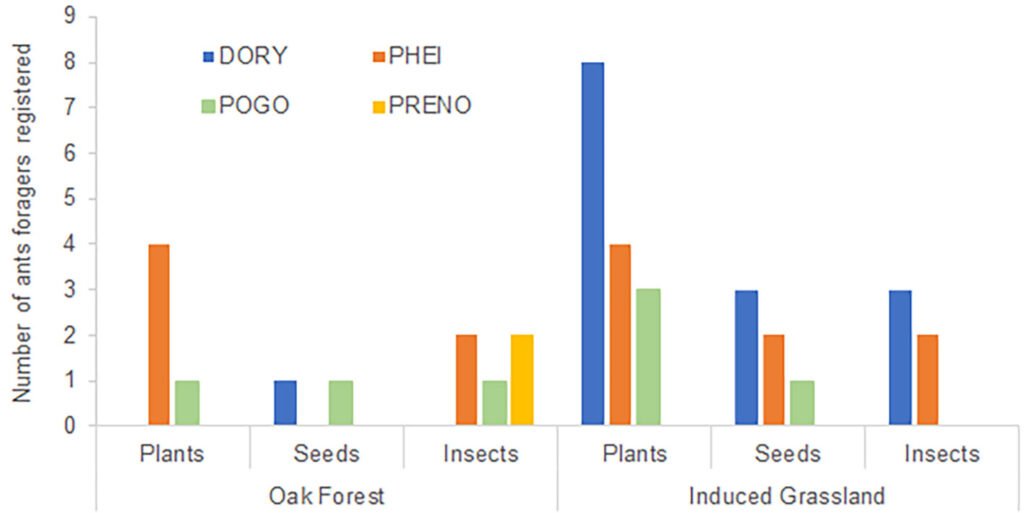

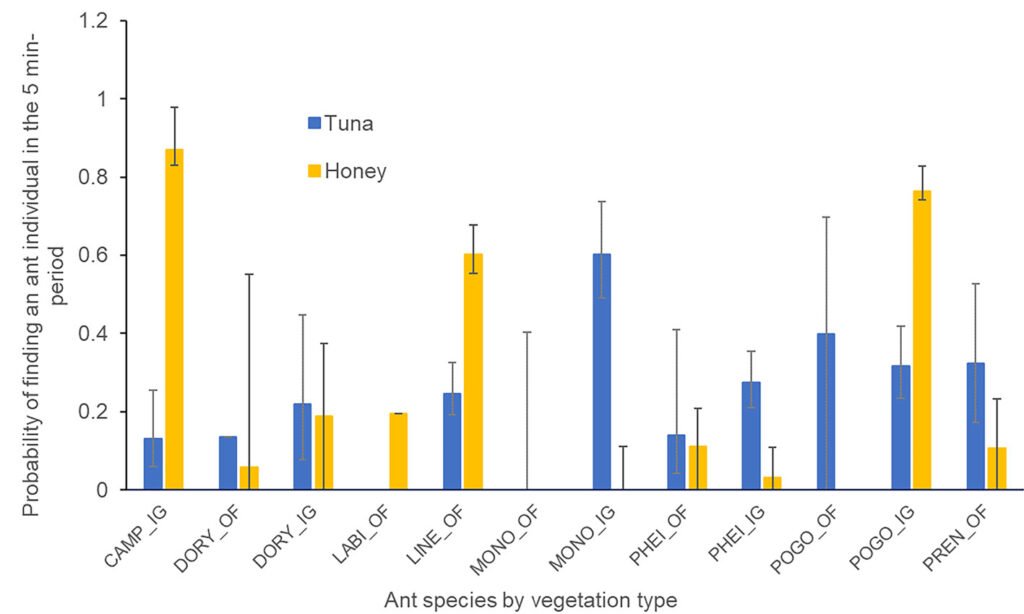

It was observed that the microhabitat most used by anurans in the forest was leaf litter. The species most associated with this type of microhabitat were D. truncatus and L. poecilochilus (Fig. 7); these species were only recorded in this coverage (Table 1). In the pasture, the highest record of species was found in bare soils and jagüeyes, with L. fuscus, L. insularum, and B. pugnax being the most associated with the latter, while R. horribilis and R. humboldti were observed mainly in bare soil (Fig. 8). In addition, these species presented the highest number of records of individuals in this coverage (Table 1). Finally, in the crop coverage, the microhabitat with the highest number of anuran records was bare soil (Fig. 9), this microhabitat was used most frequently by R. humboldti, R. horribilis, and P. brachyops which were the species with the highest number of individuals recorded; this microhabitat was also used by E. panamensis, which was the only species present in this cover (Table 1).

Discussion

In this study, 19 species of anurans and 1 casual record were identified, for a total of 20 species, this being a slightly smaller number than the 21 species recorded in the SFF Los Colorados 2018-2023 Management Plan (Jiménez et al., 2018). Craugastor raniformis (Boulenger, 1896), Pseudopaludicola pusilla (Ruthven, 1916), and Lectodactylus fragilis (Brocchi, 1877) were not observed in our study, possibly due to lack of sampling in some areas of the SFF Los Colorados. Their occurrence cannot be ruled out, since they were recorded by Acosta-Galvis (2012) in the Montes de María. This study reports C. raniformis in the forest, in ravines (on rocks), on leaf litter, and in shrubby vegetation; P. pusilla in crop areas and on the edge of plain forests, on sandy substrates and in cracks after rains; L. fragilis in flat areas, around seasonal ponds, and near swamps.

Scarthyla, D. ebraccatus, and L. savagei are added to the anuran fauna of the SFF Los Colorados, which shows that it is necessary to continue carrying out studies in the subregions of STDF, including the protected areas of the plains of the Caribbean region, valleys of the Magdalena and Cauca Rivers, Catatumbo, and enclaves of the Patía Valley. Amphibian diversity is poorly known due to the lack of biological studies (Urbina-Cardona et al., 2014).

Sampling carried out in the first 3 months of the year (January, February, and March) regularly corresponds to the dry season (Rangel & Carvajal-Cogollo, 2012). However, rains occurring in these months is a consequence of the effects of the La Niña phenomenon in Colombia for 2022 (Guzmán-Ferraro & García, 2022).

Figure 4. Histogram and box plot of daily ambient temperature across the sampling months; temperature (A, B), rainfall (C).

Increases were observed in the specific richness and in the recorded number of individuals as rainfall increased (especially in April and June), so it was considered that the rainfall regime prior to sampling played an important role in the observation of anurans. These increases in richness and mainly in the number of individuals are attributed to higher activity and the reproductive strategies of some species, which take advantage of the rains to reproduce and lay eggs in temporary ponds. The rains caused greater activity and detectability of some species that were observed vocalizing in small ponds that had formed and cow dams.

Figure 5. Monthly trend of average richness (A), abundance (B), and diversity (C, D) for each vegetation cover type.

Only some amplexuses were recorded but we did not record nesting or reproduction events. Some of the species have explosive activity, which generates an increase in the number of individuals, as is the case of R. horribilis and other species (Vargas-Salinas et al., 2019); some other species vocalizing included Engytomops pustulosus in some ponds and Dendropsophus microcephalus in the emerging vegetation around the cow dams. However, it is worth mentioning that the frequency and intensity of the La Niña phenomenon due to climate change could alter the reproductive times of anurans, causing many species to have early reproduction, which would bring about temporal overlaps of the species that would generate changes in the structure of the assembly (Lawyer & Morin, 1993).

Figure 6. Jaccard similarity dendrogram for the anuran samples from the SFF Los Colorados.