How relevant is the relationship between ostiole size and wasp head shape in the Ficus-Agaonidae mutualistic interaction?

Nadia Castro-Cárdenas, Armando Navarrete-Segueda, Guillermo Ibarra-Manríquez *

Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Investigaciones en Ecosistemas y Sustentabilidad, Antigua carretera a Pátzcuaro No. 8701, Colonia Ex Hacienda de San José de La Huerta, 58190, Morelia, Michoacán, Mexico

*Corresponding author: gibarra@iies.unam.mx (G. Ibarra-Manríquez)

Received: 07 February 2024; accepted: 27 May 2024

Abstract

The mutualism between Ficus species (Moraceae) and their pollinating wasps (Agaonidae) is a widely recognized coevolutionary model. In Ficus species from the Paleotropic, it has been determined that the ostiole acts as a morphological filter that affects the head dimensions of pollinating female wasps. Here, for the first time, the allometric relationship between ostiole size (diameter and length) and the shape of the head (length/width) of pollinating wasps is quantitatively explored in 6 Neotropical Ficus species (3 sect. Americanae and 3 sect. Pharmacosycea). In the case of sect. Americanae, wasp head shape was significantly correlated only with ostiole length, while in sect. Pharmacosycea both ostiole variables were correlated with head shape. The ordination analysis (NMDS) clearly reflected associations of these traits in species for both sections. The results support what has been interpreted in previous studies as reciprocal evolution between the analyzed traits, which contribute, along with other morphological and ecological traits, to the specificity between Ficus species and their pollinating wasps.

Keywords: Mutualism; Ostiole; Pegoscapus; Tetrapus

© 2024 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Biología. Este es un artículo Open Access bajo la licencia CC BY-NC-ND

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

¿Qué tan relevante es la relación entre el tamaño del ostíolo y la forma de la cabeza de las avispas en la interacción mutualista Ficus-Agaonidae?

Resumen

El mutualismo entre Ficus (Moraceae) y sus avispas polinizadoras (Agaonidae) es un modelo coevolutivo ampliamente reconocido. En especies de Ficus del Paleotrópico, se ha determinado que el ostíolo actúa como un filtro morfológico que afecta las dimensiones de la cabeza de las hembras polinizadoras. Por primera vez se explora, cuantitativamente, la relación alométrica entre el tamaño del ostíolo (diámetro y largo) y la forma de la cabeza (largo/ancho) de las avispas polinizadoras en 6 especies de Ficus neotropicales (3 sect. Americanae y 3 sect. Pharmacosycea). En el caso de sect. Americanae, la forma de la cabeza de las avispas se correlacionó significativa y únicamente con el largo del ostíolo, mientras que en la sect. Pharmacosycea, ambas variables del ostíolo se correlacionaron con la forma de la cabeza. El análisis de ordenación (NMDS) reflejó claramente asociaciones de estos atributos por especie para ambas secciones. Los resultados apoyan lo expuesto en estudios previos de una evolución recíproca entre los atributos analizados, lo que contribuye, en conjunto con otros atributos morfológicos y ecológicos, a la especificidad entre Ficus y sus avispas polinizadoras.

Palabras clave: Mutualismo; Ostíolo; Pegoscapus; Tetrapus

Introduction

The interaction between species of the genus Ficus L. (Moraceae) and wasps of the family Agaonidae Walker (Hymenoptera) is a classic example of a mutualistic interaction, in which the phenomena of co-diversification, co-speciation, and co-evolution are well documented (Borges, 2021; Bronstein, 1988; Jousselin et al., 2003; Rønsted et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2019; Wiebes, 1979) and is estimated to date to ca. 74.9 Ma (60.0-101.9 Ma; Cruaud et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2019). For many years it was assumed that 1 Ficus species was pollinated exclusively by 1 wasp species (e.g., Ramírez, 1970; Wiebes, 1966, 1979), but a growing amount of evidence contradicts this assumption (Cook & Rasplus, 2003; Cook & Segar, 2010; Herre et al., 2008; Machado et al., 2005; Molbo et al., 2003; Oldenbeuving et al., 2023; Peng et al., 2008; Su et al., 2008; Weiblen, 2002).

Regardless of the degree of specificity, this ancestral and close mutualistic relationship involves complex morphological modifications (Clement et al., 2020; Galil & Eisikowich, 1968). The flowers of Ficus species are found inside an urn-shaped inflorescence (syconium). The development of the syconium traditionally has been divided into 5 phases (Galil & Eisikowich, 1968; Ibarra-Manríquez et al., 2012; Verkerke, 1989): A) floral or female, B) receptive or female, C) interfloral, D) male), and E) post floral. Pollinators can only access the flowers during phase B, through the ostiole, which is an apical opening in the syconium made up of numerous overlapping bracts (Castro-Cárdenas et al., 2022; Machado et al., 2013; van Noort & Compton, 1996; Verkerke, 1989). The ostiole plays a fundamental role in the specificity of pollinating wasps among the different sections of the genus Ficus, since it acts as a physical barrier, blocking the entry of non-pollinating wasps and/or regulating the size of the pollinating wasps that are able to reach the syconial cavity (Chen et al., 2001; Janzen, 1979; Jousselin et al., 2003; Liu et al., 2011; Ramírez, 1974; Verkerke, 1989).

One of the morphological modifications recorded for Agaonidae wasps was suggested by Ramírez (1974), who proposed that the shape of the head of female wasps presents various modifications that facilitate their passage through the ostiole, indicating that heads that are subquadrangular or subhemispherically flattened (usually as long as broad across the eyes) have been recorded in Ficus species in different groups (e.g., subgen. Ficus or the sections Americanae or Conosycea), whose syconia present spirally arranged ostiolar bracts. On the other hand, wasps with thin elongated heads have been recorded in Ficus species possessing syconia with linearly arranged ostiole bracts, which mostly point downwards (e.g., sections Galoglychia or Pharmacosycea).

van Noort & Compton (1996) evaluated the convergence in head shape between wasps from 2 subfamilies (Agaonidae and Sycoecinae), pollinators and non-pollinators, respectively, of the same Ficus species (subg. Urostigma sect. Galoglychia). These authors suggested that selection would have favored convergence in the shape of the head of both lineages of wasps, due to the pressure derived from achieving a successful entry of pollinating females into the syconium cavity. Furthermore, they emphasized that the length of the ostiole is the main factor in determining this trait in wasps, since the arrangement of the ostiole bracts in sect. Galoglychia is constant between species (Verkerke, 1989). However, the authors suggested that confirmation of their results required obtaining measurements of the ostiole during phase B of syconium development since the measurements used in the analysis were obtained from taxonomic literature. This is an important proposal, considering that there are records of Ficus species in which the size of the syconium differ among the different stages of development (Delgado-Pérez et al., 2020; Piedra-Malagón et al., 2019). Finally, Jousselin et al. (2003) reconstructed the evolution of the shape of the ostiole (spiral or linear) and the shape of the head of pollinating wasps (short or elongate) using molecular markers only (ITS and ETS) and concluded that both traits are correlated throughout the genus Ficus.

The genus Ficus is represented in the Neotropics by the subgenera Pharmacosycea (Miq.) Miq. and Spherosuke Raf. (Berg, 1989; Pederneiras et al., 2015), whose sections are endemic to the American continent (Pharmacosycea (Miq.) Griseb. and Americanae (Miq.) Corner, respecti-

vely). The diversity of section Pharmacosycea is estimated to be 20 species, which are exclusively pollinated by wasps of the genus Tetrapus Mayr 1885, whose heads are longer than wide. The sect. Americanae includes a larger number of species (ca. 120) whose pollinators belong to the genus Pegoscapus Cameron 1906, which possess subquadrangular or subhemispherical heads (Berg, 1989; Jousselin et al., 2003; Ramírez, 1974).

The main objective of the present study was to determine the relationship between the size of the ostiole in species belonging to the sections of Ficus and the shape of the heads of pollinating wasps, a relationship that has not been previously analyzed quantitatively. The inclusion of Ficus species belonging to the 2 Neotropical sections is relevant, since it will allow a further evaluation between fig and fig wasp traits from a phylogenetic context (Jousselin et al., 2003).

Materials and methods

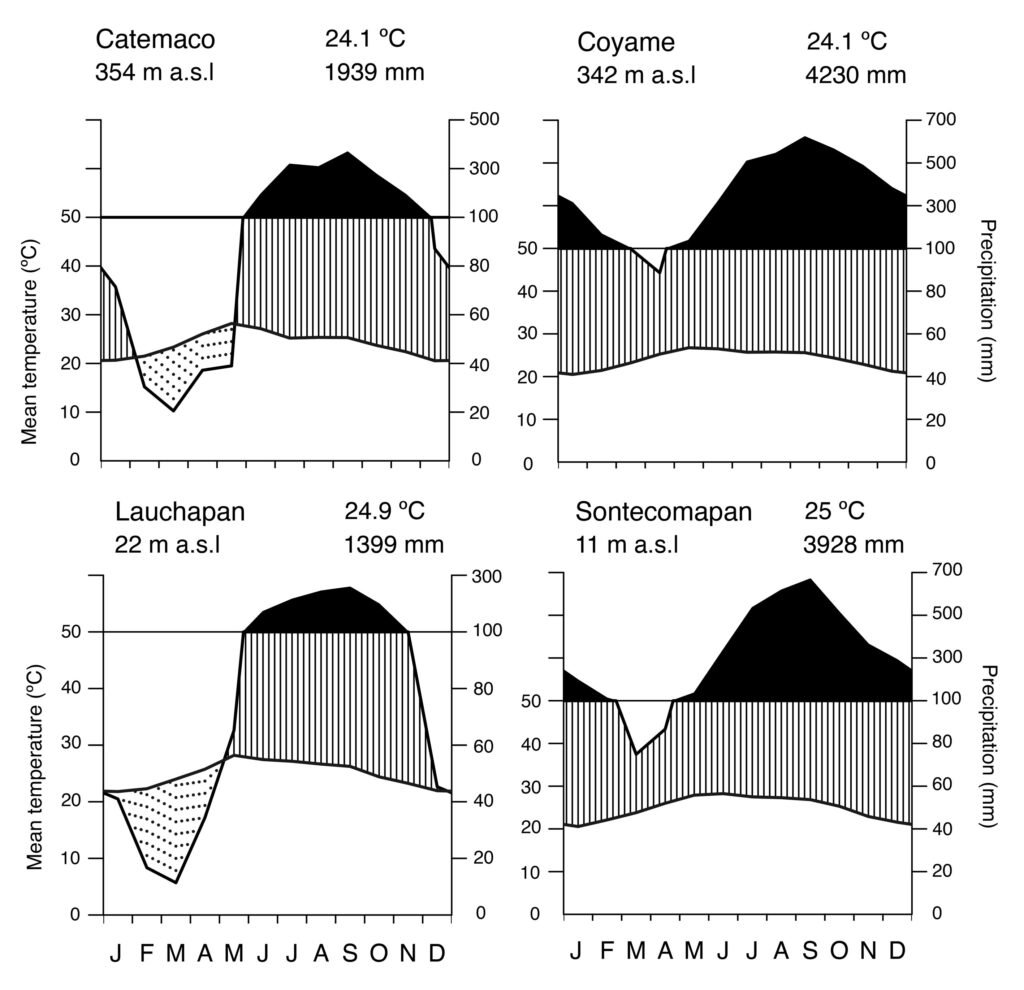

Fieldwork was carried out in the NW portion of the Los Tuxtlas region in the state of Veracruz, Mexico (Fig. 1). This region forms part of the Upper Tertiary and Middle Quaternary volcanic complex and is composed of basaltic andesite and basalt rock (Verma et al., 1993) and is bordered by Holocene lava flows (Nelson & Gonzalez-Caver, 1992). The study area reaches elevations between 100 and 600 m. The predominant climate is warm and humid, with rain all year round (A), an average annual temperature between 24.1 and 25 °C, and an average annual precipitation of 1,939 to 3,928 mm (Fig. 2; SMN, 2010). Rainfall is more frequent and abundant during the summer, whereas a drier season occurs between March to May, the latter being the driest month (SMN, 2010; Soto, 2004). The species richness of vascular plants documented for the Los Tuxtlas region is 2,548 species (2,391 native; 307 are endemic to Mexico), distributed in 208 families and 1,018 genera (Villaseñor et al., 2018). The families with the highest number of species are Fabaceae (212), Orchidaceae (171), Asteraceae (150), Rubiaceae (143), and Poaceae (82). Villaseñor et al. (2018) point out that the predominant biome in the region is the humid tropical forest. The location of the individuals of Ficus sampled in the present study are indicated in Figure 1.

The collection and measurement of syconia and pollinating wasps. Three species were chosen from each section of Ficus, which represented the size range of the syconia described for both sections in Mexico (Ibarra-Manríquez et al., 2012): F. apollinaris Dugand, F. insipida Willd., and F. yoponensis Desv. from sect. Phamacosycea, and F. colubrinae Standl., F. isophlebia Standl., and F. obtusifolia Kunth from sect. Americanae. Detailed descriptions and illustrations of the species can be consulted in Ibarra-Manríquez et al. (2012), Cornejo-Tenorio et al. (2019), and Hernández-Esquivel et al. (2020).

The material collected included 5 individuals per Ficus species with syconia in the development phases B and D (Galil & Eisikowitch, 1968; Ibarra-Manríquez et al., 2012). The collected syconia for phase B allowed us to measure the size of the ostiole at the time when the pollinating wasps enter the syconium, whereas for the syconium in phase D (male phase), we were able to capture the emerging pollinating wasps. In phase B syconia, the ostioles were dissected and fixed and stored in 70% ethanol. Phase D syconia were placed in airtight bags until the pollinating wasps emerged and then each wasp was collected with a small brush, fixed, and stored in 70% ethanol. Wasps were identified to genus level using identification keys (Bouček, 1993; Rasplus & Soldati, 2006) and classified into morphospecies (Fig. 3). We measured the ostioles for a total of 150 syconia and 170 individuals of pollinating wasps.

Figure 1. Study site localization and sampling area. A) Veracruz state (black area) in Mexico; B) location of the Los Tuxtlas Region (black dot) within Veracruz, Mexico; C) syconium and wasps’ collection points are shown in the Los Tuxtlas Region and a zoom of the vegetation cover is shown in areas for each species included in the study (D – I). Points were placed on base maps (OpenStreetMap and World Imagery) of ArcGIS® software.

The size of the ostiole was recorded using 3 measurements: 2 diameters of the area that is covered by the superficial ostiolar bracts (Fig. 4A, B), and the length, which indicates the distance between the internal and superficial ostiolar bracts (Fig. 4C, D). The head of pollinating wasp individuals were dissected and measured under a Zeiss stereoscopic microscope model Axio Zoom V16. We recorded the length (the distance between the posterior margin of the head and the apex of the jaw) and the width at maximum eye level (Fig. 4E, F). Both measurements allowed us to determine the shape of the wasp’s head (average head length to head width ratio), as described by van Noort & Compton (1996).

Data analysis. We calculated the Pearson correlation coefficients between diameter 1, diameter 2, and length of the ostiole. We also applied generalized linear models and carried out multiple comparisons using the ‘multcomp’ package to assess differences in ostiole diameter and Agaonidae wasps’ length/width ratio among species of each section. We performed a Nonmetric Multidimensional Scaling (NMDS) analysis to examine the multivariate relationship of the ostiole proportions (diameters and length) and head size (length and width) among species of each section of Ficus. We applied the decostand function of ‘Vegan’ to obtain a standardized matrix constructed with values to reduce the extremes values effect (Oksanen et al., 2019). We implemented NMDS with Bray-Curtis’s dissimilarity. Finally, we added convex hulls with the ordihull function of ‘vegan’ to highlight point clusters based on species. Since NMDS uses rank order information, this technique provides a highly flexible quantitative method that allows distribution-free inferences and, because it has a high flexibility in the number of observations, it is particularly useful with unbalanced experimental designs to explore the proximities and resemblances in the structure of the data among groups (Tong, 1992). Therefore, these analyses allowed us to identify the structure and association degree of ostiole-wasp heads among species of each section. All the analyses were conducted using R software.

Results

We found a positive correlation between the 2 diameters of the ostiole, both for sect. Americanae (0.99, p < 0.000) and for sect. Pharmacosycea (0.96, p < 0.001). In the latter section, a high positive correlation was also obtained between the length of the ostiole and both diameters (0.93, p < 0.000), a relationship that was lower for sect. Americanae (diameter 1, 0.37 and diameter 2, 0.39, p < 0.01). Figure 5 shows that the diameter of the ostiole differs significantly between the 3 species included in each section (Americanae, F2, 73 = 2156922, p < 0.000; Pharmacosycea, F2, 74 = 3.81, p < 0.000). The same result was found for the species from both sections when considering the length of the ostiole (Americanae, F2, 71 = 0.74, p < 0.000; Pharmacosycea, F2, 74 = 1.88, p < 0.000).

Figure 2. Ombrothermal diagrams of meteorological stations in the Los Tuxtlas Region, Veracruz. The data correspond to 30 years of records from the SMN (2010).

Figure 3. Heads of pollinating wasps. A) Pegoscapus sp. 1 (Ficus colubrinae); B) Pegoscapus sp. 2 (F. isophlebia); C) Pegoscapus sp. 3 (F. obtusifolia); D) Tetrapus sp. 1 (F. apollinaris); E) Tetrapus sp. 2 (F. insipida); F) Tetrapus sp. 3 (F. yoponensis). Scale bar: 200 μm.

Figure 4. Variables considered in the study. A-B) Frontal view of the ostiole; D1, diameter 1 and D2, diameter 2; C-D) longitudinal section of the ostiole; E-F) frontal view of the head of pollinating wasps; L, length of the head (from the protuberances of the clypeal margin to the mandible) and W, width of the head (Interocular distance). A, C) Ficus colubrinae; B) F. yoponensis; D) F. insipida; E) Pegoscapus sp. 1; F) Tetrapus sp. 1. Scale bars: a, c, d = 500 μm, b = 250 μm, e = 50 μm, f = 100 μm.

Figure 5. Diameter of the ostiole in the Americanae and Pharmacosycea sections. Syconia by species (25). Different letters indicate significant differences at a p < 0.001 level.

A positive correlation was recorded between the length and width of the head of the pollinating wasps in both genera; however, the relationship was greater in Pegoscapus than in Tetrapus (rho = 0.85 and 0.75, respectively). The wasps in this latter genus have elongated heads and differ from those recorded in the Pegoscapus species, which are subquadrangular (Fig. 6). For the case of sect. Americanae, the head proportion of F. isophlebia wasps differed significantly from F. colubrinae and F. obtusifolia (F2, 37 = 0.079, p < 0.000), while for sect. Pharmacosycea, differences were also found between the 3 species analyzed (F2, 74 = 0.291, p < 0.000) (Fig. 6).

In the correlation analysis between the size of the ostiole (diameter 1 and length) and the shape of the wasp’s head, sect. Americanae only showed significance for ostiole length (0.6, p < 0.000), while for Pharmacosycea both ostiole variables are correlated, although with low values (diameter, 0.35, p < 0.01; length – 0.25, p < 0.05). The ordination analysis (NMDS) reflects associations by species (Fig. 7). For sect. Americanae (stress = 0.01), the species with smaller ostioles (F. colubrinae and F. isophlebia) are found at 1 end of the ordination, with a greater width in the dispersion of the data for F. isophlebia. Likewise, in sect. Pharmacosycea (stress = 0.02), the species with the smallest ostiole size (F. apollinaris and F. yoponensis) are located at 1 end of the ordination, distant from F. insipida, which shows greater variation in the traits analyzed.

Figure 6. Head length/width of wasps by section. Distict letters indicate significant differences at p < 0.001 level.

Discussion

The present study is the first to quantitatively analyze the relationship between the dimensions of the ostiole and the shape of the head of pollinating wasps for the Neotropical sections of the genus Ficus and it contributes to support the reciprocal evolution in their mutualism. Here, it is important to point out that our results were obtained during phase B of syconia development, which was not the case in the study by van Noort & Compton (1996), who used measurements of syconia size from the literature. In addition to the above, Castro-Cárdenas et al. (2022) hypothesized that the ostiole could play a selective filter role that only allows the entry of a particular pollinating wasp morphospecies into the syconium, as has been suggested in previous studies (Dunn, 2020; Herre, 1989; Jandér et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2011). The differences found for the diameter and length of the ostioles among the species studied in both sections (Fig. 5) support this hypothesis.

As regards to the shape of the heads in the Agaonidae wasps proposed by Ramírez (1974), for the genera recorded in America, that information coincides with our results, since the species belonging to the genus Pegoscapus presented subquadrangular heads, while those of Tetrapus were clearly more elongated than wide (Figs. 3, 6). With respect to the 2 categories in wasp head shape (short heads, with a ratio ≥ 1; elongate, ratio ≤ 1), proposed by Jousselin et al. (2003), the ranges of variation found in the species evaluated (Americanae, 0.9-1.2; Pharmacosycea, 0.9-1.6), do not coincide exactly, although short and elongate are equivalent terms to those proposed by Ramírez (1974).

The close relationship between the metrics of the ostiole and the head of the pollinating wasps in the American sections (Fig. 7) coincides with previous studies of a reciprocal evolution between both mutualistic partners (Cook & Segar, 2010; Galil, 1977; Ramírez, 1974; Weiblen, 2002). Furthermore, interspecific variation in head shape suggests a closer modification, at the species level, in response to ostiole morphology, as has been argued in various previous studies (Cook & Rasplus, 2003; Cook & Segar, 2010; Jousselin et al., 2003; Liu et al., 2011; Ramírez, 1974; Rasplus et al., 2020; van Noort & Compton, 1996). Similar patterns have been reported for other genera of the family Agaonidae, such as Alfonsiella Waterston, Allotriozoon Grandi, Courtella Kieffer, Elisabethiella Grandi, and Pleistodontes Saunders (Dunn et al., 2008; van Noort & Compton, 1996).

The close correlation recorded between the shape of the head of the pollinating wasps and the size of the ostiole coincides with that proposed by Cruaud et al. (2012) and van Noort & Compton (1996), who indicate that these traits are part of a complex mechanism (the lock-and-key shapes of fig ostioles and wasp heads), that determines the specificity between Ficus species and their pollinating wasps. As previously mentioned, this mechanism may explain the role of the ostiole, not only as a physical filter for pollinators but also as a chemical filter, since it is associated with the emission of volatiles for the attraction of legitimate pollinating wasps (Castro-Cárdenas et al., 2022; Okamoto & Su, 2021; Wang et al., 2013). This mechanism is considerably important since it has been shown that closely related species can emit different volatile compounds to attract their pollinating wasps (Okamoto & Su, 2021; Oldenbeuving et al., 2023; Souto-Vilarós et al., 2018).

Figure 7. Grouping based on the characteristics of the diameters and length of the ostiole and the shape of the head of the wasps in the species of the Ficus sections included in the study.

A critical aspect for the advancement in the understanding of the connection between the head shape of pollinating wasps and the dimensions of the ostiole is to carry out studies with a greater geographic scope, since the taxonomy of Ficus species in the Neotropical sections is not completely resolved (Berg, 1989; Ibarra-Manríquez et al., 2012). Global studies are required to resolve the taxonomic complexes that have been detected (Berg, 2007; Hernández-Esquivel et al., 2020; Pederneiras et al., 2023). These studies need to be performed together with a precise identification of the pollinating wasps, since there is evidence of Ficus species with more than 1 wasp pollinator (Jackson et al., 2008; Machado et al., 2005; Molbo et al., 2003; Su et al., 2008), some of which can be cryptic (Haine et al., 2006; Molbo et al., 2003). Future studies where these elements can be integrated are thus required to validate and estimate the possible contribution of each trait in this intriguing mutualism.

Acknowledgements

The first author acknowledges scholarship provided by Consejo Nacional de Humanidades, Ciencias y Tecnologías (Conahcyt) and the DGAPA-UNAM (Dirección General de Asuntos del Personal Académico – Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México) for the award of a postdoctoral fellowship grant. A. Navarrete-Segueda thanks the support received from the Consejo Nacional de Humanidades, Ciencias y Tecnologías through the 2022 (1) postdoctoral fellowship grant of the “Estancias Posdoctorales por México – Académica”. We thank Ma. Guadalupe Cornejo Tenorio for her help in measuring the wasp heads and Iván Leonardo Ek Rodríguez for their collaboration in the fieldwork. We are grateful to Silvia Espinosa Matías and Orlando Hernández Cristóbal for technical support with SEM pictures. Thanks to the Laboratorio Nacional de Análisis y Síntesis Ecológica (LANASE) of the ENES Morelia, UNAM, for their microscopy facilities and the Estación de Biología Tropical de Los Tuxtlas, Instituto de Biología, UNAM, for logistical support. We appreciate the support of Rosamond Coates in translating the English version of the manuscript. Finally, we are also grateful to two reviewers for their valuable comments to improve our manuscript.

References

Berg, C. C. (1989). Classification and distribution of Ficus. Experientia, 45, 605–611. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01975677

Berg, C. C. (2007). Proposals for treating four species complexes in Ficus subgenus Urostigma section Americanae (Moraceae). Blumea, 52, 295–312. https://doi.org/10.3767/000651907X609034

Bronstein, J. L. (1988). Mutualism, antagonism, and the fig-pollinator interaction. Ecology, 69, 1298-1302. https://doi.org/10.2307/1941287

Borges, R. M. (2021). Interactions between figs and gall-inducing fig wasps: Adaptations, constraints, and unanswered questions. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 9, 685542. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2021.685542

Bouček, Z. (1993). The genera of chalcidoid wasps from Ficus fruit in the New World. Journal of Natural History, 27, 173–217. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00222939300770071

Castro-Cárdenas, N., Vázquez-Santana, S., Teixeira, S. P., & Ibarra-Manríquez, G. (2022). The roles of the ostiole in the fig-fig wasp mutualism from a morpho-anatomical perspective. Journal of Plant Research, 135, 739–755. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10265-022-01413-9

Chen, Y.-R., Chou, L.-S., & Wu, W.-J. (2001). Regulation of fig wasps entry and egress: The role of ostiole of Ficus microcarpa L. Formosan Entomology, 21, 171–182, https://doi.org/10.6661/TESFE.2001014

Clement, W. L., Bruun Lund, S., Cohen, A., Kjellberg, F., Weiblen, G. D., & Rønsted, N. (2020). Evolution and classification of figs (Ficus) and their close relatives (Castilleae) united by involucral bracts. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society, 193, 316–339. https://doi.org/10.1093/botlinnean/boaa022

Cook, J. M., & Rasplus J.-Y. (2003). Mutualists with attitude: Coevolving fig wasps and figs. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 18, 241–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-5347(03)00062-4

Cook, J. M., & Segar, S. T. (2010). Speciation in fig wasps. Ecological Entomology, 35, 54–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2311.2009.01148.x

Cruaud, A., Ronsted N., Chantarasuwan, B., Chou, L. S., Clement, W. L., Couloux, A. et al. (2012). An extreme case of plant-insect codiversification: figs and fig-pollinating wasps. Systematic Biology, 61, 1029–1047. https://doi.org/10.1093/sysbio/sys068

Cornejo-Tenorio, G., Ibarra-Manríquez, G., & Sinaca-Colín, S. (2019). Flora de Los Tuxtlas. Guía ilustrada. Ciudad de México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Delgado-Pérez, G., Vázquez-Santana, S., Cornejo-Tenorio, G., & Ibarra-Manríquez, G. (2020). Morfoanatomía de las fases de desarrollo del sicono de Ficus tuerckheimii (subg. Spherosuke, sect. Americanae, Moraceae). Botanical Sciences, 98, 570–583. https://doi.org/10.17129/botsci.2631

Dunn, D. W. (2020). Stability in fig tree-fig wasp mutualisms: How to be a cooperative fig wasp. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 130, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1093/biolinnean/blaa027

Dunn, D. W., Yu, D. W., Ridley, J., & Cook, J. M. (2008). Longevity, early emergence and body size in a pollinating fig wasp – Implications for stability in a fig-pollinator mutualism. Journal of Animal Ecology, 77, 927–935. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2656.2008.01416.x

Galil, J. (1977). Fig biology. Endeavour, 1, 52–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-9327(77)90106-5

Galil, J., & Eisikowitch, D. (1968). On the pollination ecology of Ficus sycomorus in East Africa. Ecology, 49, 259–269. https://doi.org/10.2307/1934454

Haine, E. R., Martin, J., & Cook, J. M. (2006). Deep mtDNA divergences indicate cryptic species in a fig-pollinating wasp. BMC Evolutionary Biology, 6, 83. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-6-83

Hernández-Esquivel, K, B., Piedra-Malagón, E. M., Cornejo-Tenorio, G., Mendoza-Cuenca, L., González-Rodríguez, A., Ruiz-Sánchez, E. et al. (2020). Unraveling the extreme morphological variation in the neotropical Ficus aurea complex (subg. Spherosuke, sect. Americanae, Moraceae). Journal of Systematics and Evolution, 58, 263–281. https://doi.org/10.1111/jse.12564

Herre, E. A. (1989). Coevolution of reproductive characteristics in 12 species of New World figs and their pollinator wasps. Experientia, 45, 637–647. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01975680

Herre, E. A., Jandér, K. C., & Machado, C. A. (2008). Evolutionary ecology of figs and their associates: recent progress and outstanding puzzles. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 39, 439–458. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.37.091305.110232

Ibarra-Manríquez, G., Cornejo-Tenorio, G., González-Castañeda, N., Piedra-Malagón, E. M., & Luna, A. (2012). El género Ficus L. (Moraceae) en México. Botanical Sciences, 90, 389–452. https://doi.org/10.17129/botsci.472

Jackson, A. P., Machado, C. A., Robbins, N., & Herre, E. A. (2008). Multi-locus phylogenetic analysis of Neotropical figs does not support co-speciation with the pollinators: the importance of systematic scale in fig/wasp cophylogenetic studies. Symbiosis, 45, 57–72.

Jandér, K. C., Dafoe, A., & Herre, E. A. (2016). Fitness reduction for uncooperative fig wasps through reduced offspring size: A third component of host sanctions. Ecology, 97, 2491–2500. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.1471

Janzen, D. H. (1979). How to be a fig. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 10, 13–51. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.es.10.110179.000305

Jousselin, E., Rasplus, J. Y., & Kjellberg, F. (2003). Convergence and coevolution in a mutualism: Evidence from a molecular phylogeny of Ficus. Evolution, 57, 1255–1269. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0014-3820.2003.tb00334.x

Liu, C., Yang, D.-R., & Peng, Y.-Q. (2011). Body size in a pollinating fig wasp and implications for stability in a fig-pollinator mutualism. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata, 138, 249–255. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1570-7458.2011.01096.x

Machado, A. F. P., de Souza, A. M., & Leitão, C. A. E. (2013). Secretory structures at syconia and flowers of Ficus enormis (Moraceae): A specialization at ostiolar bracts and the first report of inflorescence colleters. Flora, 208, 45–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.flora.2012.12.005

Machado, C. A., Robbins, N., Gilbert, M. T. P., & Herre, E. A. (2005). Critical review of host specificity and its coevolutio-

nary implications in the fig/fig-wasp mutualism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 102 (suppl._1), 6558–6565. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0501840102

Molbo, D., Machado, C. A., Sevenster, J. G., Keller, L., & Herre, E. A. (2003). Cryptic species of fig-pollinating wasps: Implications for the evolution of the fig-wasp mutualism, sex allocation, and precision of adaptation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 100, 5867–5872. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0930903100

Nelson, S. A., & Gonzalez-Caver, E. (1992). Geology and K-Ar dating of the Tuxtla Volcanic Field, Veracruz, Mexico. Bulletin of Volcanology, 55, 85–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00301122

Okamoto, T., & Su, Z.-H. (2021). Chemical analysis of floral scents in sympatric Ficus species: highlighting different compositions of floral scents in morphologically and phylogenetically close species. Plant Systematics and Evolution, 307, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00606-021-01767-y

Oksanen, J., Blanchet, F. G., Friendly, M., Kindt, R., Legendre, P., McGlinn, D. et al. (2019). Vegan: Community ecology package. In R package version 2.5-6 (p. 296). https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412971874.n145

Oldenbeuving, A., Gómez-Zúniga, A., Florez-Buitrago, X., Gutiérrez-Zuluaga, A. M., Machado, C. A., Van Dooren, T. J. M. et al. (2023). Field sampling of fig pollinator wasps across host species and host developmental phase: Implications for host recognition and specificity. Ecology and Evolution, 13, e10501. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.10501

Pederneiras, L. C., Carauta, J. P. P., Neto, S. R., & de Freitas, V. (2015). An overview of the infrageneric nomenclature of Ficus (Moraceae). Taxon, 64, 589–594. http://dx.doi.org/10.12705/643.12

Pederneiras, L. C., Zamengo, H. B., Plata-Castro, A. D., Romaniuc-Neto, S., & de Freitas, V. (2023). Ficus sect. Americanae ser. Kinuppii: a ramiflorous group of Neotropical fig trees. Brittonia, 75, 249-268. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12228-023-09750-2

Peng, Y. Q., Duan, Z. B., Yang, D. R., & Rasplus, J. Y. (2008). Cooccurrence of two Eupristina species on Ficus altissima in Xishuangbanna, SW China. Symbiosis, 45, 9–14.

Piedra-Malagón, E. M., Hernández-Ramos, B., Mirón-Monterrosas, A., Cornejo-Tenorio, G., Navarrete-Segueda, A., & Ibarra-Manríquez, G. (2019). Syconium development in Ficus petiolaris (Ficus, sect. Americanae, Moraceae) and the relationship with pollinator and parasitic wasps. Botany, 97, 190–203. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjb-2018-0095

Ramírez, B. W. (1970). Host specificity of fig wasps (Agaonidae). Evolution, 24, 680–691. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.1970.tb01804.x

Ramírez, B. W. (1974). Coevolution of Ficus and Agaonidae. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden, 61, 770–780. https://doi.org/10.2307/2395028

Rasplus, J.-Y., Rodriguez, L. J., Sauné, L., Peng, Y.-Q., Bain, A., Kjellberg, F. et al. (2020). Exploring systematic biases, rooting methods and morphological evidence to unravel the evolutionary history of the genus Ficus (Moraceae). Cladistics, 37, 402–422. https://doi.org/10.1111/cla.12443

Rasplus, J. Y., & Soldati, L. (2006). Familia Agaonidae. In: F. Fernández y M. J. Sharkey, (Eds.) Introducción a los Hymenoptera de la Región Neotropical (pp. 683-698). Bogotá: Sociedad Colombiana de Entomología & Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

Rønsted, N., Weiblen, G. D., Cook, J. M., Salamin, N., Machado, C. A., & Savolainen, V. (2005). 60 million years of co-divergence in the fig-wasp symbiosis. Proceedings of the Royal Society London B, 272, 2593–2599. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2005.3249

SMN (Servicio Metereológico Nacional). (2010). Información climatológica por estado (document on line). Servicio Meteorológico Nacional. Available at: https://smn.conagua.gob.mx/es/informacion-climatologica-por-estado?estado=ver

Soto, M. (2004). El Clima. In S. Guevara, J. Laborde, & G. Sánchez-Río (Eds.), Los Tuxtlas. El paisaje de la sierra. Xalapa: Instituto de Ecología A.C./ Unión Europea.

Souto-Vilarós, D., Proffit, M., Buatois, B., Rindos, M., Sisol, M., Kuyaiva, T. et al. (2018). Pollination along an elevational gradient mediated both by floral scent and pollinator compatibility in the fig and fig-wasp mutualism. Journal of Ecology, 106, 2256–2273. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2745.12995

Su, Z. H., Iino, H., Nakamura, K., Serrato, A., & Oyama, K. (2008). Breakdown of the one-to-one rule in Mexican fig-wasp associations inferred by molecular phylogenetic analysis. Symbiosis, 45, 73–81.

Tong, S. T. Y. (1992). The use of non-metric multidimensional scaling as an ordination technique in resource survey and evaluation: A case study from southeast Spain. Applied Geography, 12, 243–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/0143-6228(92)90042-L

van Noort, S., & Compton, S. G. (1996). Convergent evolution of agaonine and sycoecine (Agaonidae, Chalcidoidea) head shape in response to the constraints of host fig morphology. Journal of Biogeography, 23, 415–424. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.1996.tb00003.x

Verkerke, W. (1989). Structure and function of the fig. Experientia, 45, 612–622. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01975678

Verma, S. P., Salazar-V., A., Negendack, J. F. W., Milán, M., Navarro, L. I., & Besch, T. (1993). Características petrográfica y geoquímicas de elementos mayores del Campo Volcánico de Los Tuxtlas, Veracruz, México. Geofísica Internacional, 32, 237–248. https://doi.org/10.22201/igeof.00167169p.1993.32.2.558

Villaseñor, J. L., Ortiz, E., & Campos-Villanueva, A. (2018). High richness of vascular plants in the tropical Los Tuxtlas Region, Mexico. Tropical Conservation Science, 11, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940082918764259

Wang, A. Y., Peng, Y.-Q., Harder, L. D., Huang, J.-F., Yang, D.-R., Zhang, D.-Y. et al. (2019). The nature of interspecific interactions and co-diversification patterns, as illustrated by the fig microcosm. New Phytologist, 224, 1304–1315. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.16176

Wang, G., Compton, S. G., & Chen, J. (2013). The mechanism of pollinator specificity between two sympatric fig varieties: a combination of olfactory signals and contact cues. Annals of Botany, 111, 173–181. https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcs250

Weiblen, G. D. (2002). How to be a fig wasp. Annual Review of Entomology, 47, 299–330. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ento.47.091201.145213

Wiebes, J. T. (1966). Provisional host catalogue of fig wasps (Hymenoptera, Chalcidoidea). Zoologische Verhandelingen, 83, 1–44.

Wiebes, J. T. (1979). Co-evolution of figs and their insect pollinators. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 10, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.es.10.110179.000245

Zhang, Q., Onstein, R. E., Little, S. A., & Sauquet, H. (2019). Estimating divergence times and ancestral breeding systems in Ficus and Moraceae. Annals of Botany, 123, 191–204. https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcy159