Marzo-2017-prueba

Consulta de ejemplares

Taxonomía y Sistemática

A new species of the genus Monstrilla (Copepoda: Monstrilloida: Monstrillidae) from the Gulf of California, Mexico

Eduardo Suárez-Morales a, *, Karl E. Velázquez-Ornelas b

a El Colegio de la Frontera Sur, Avenida Centenario Km 5.5, 77014 Chetumal, Quintana Roo, Mexico

b Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Ciencias del Mar y Limnología, Unidad Mazatlán, Joel Montes Camarena s/n, 82040 Mazatlán, Sinaloa, Mexico

*Corresponding author: esuarez@ecosur.mx (E. Suárez-Morales)

Received: 23 September 2023; accepted: 24 June 2024

http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:55476587-382E-4014-9EB2-F111CFF305DC

Abstract

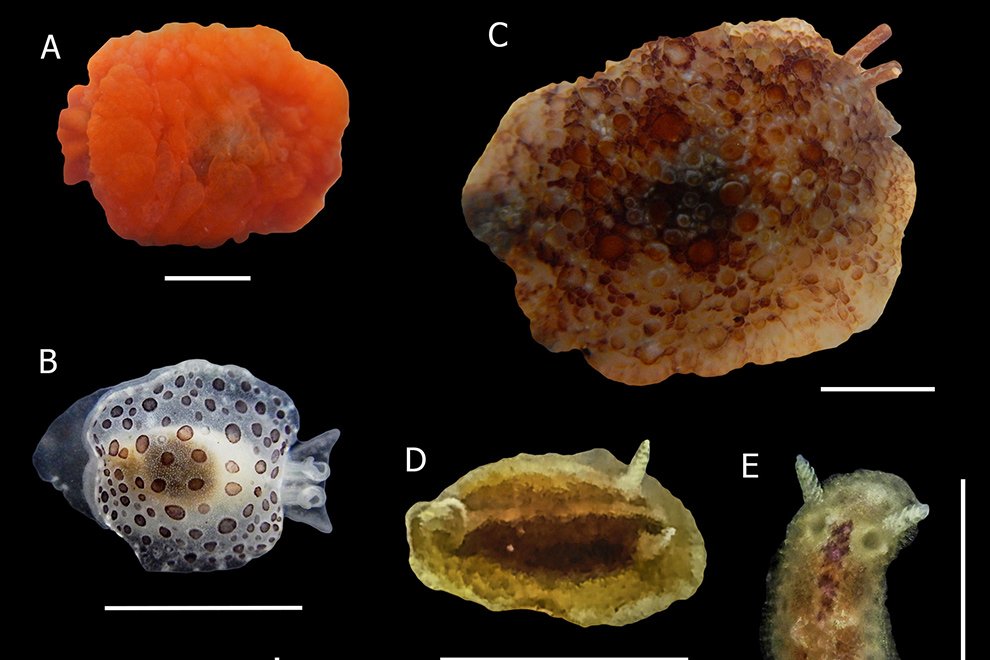

Based on deep-water (700-750 m) biological samples obtained from the southern Gulf of California, Pacific coast of Mexico, a new species of the monstrilloid copepod genus Monstrilla Dana, 1849 is described based on a single subadult female collected close to the bottom with an epibenthic sledge. Monstrilla hendrickxi sp. n. is distinguished by a unique combination of characters including: 1) no trace of eyes; 2) strong, thick antennules with segments 2-4 partly fused; 3) strongly developed apical elements on antennular segment 5 and spinous processes on segments 2-5; and 4) bilobed fifth legs with 2 apical setae on the exopodal lobe and a digitiform, unarmed endopodal lobe. The new species exhibits some affinity with surface-dwelling species of Monstrilla that have 2 setae on the exopodal lobes of the fifth legs. This is the fifth record of a species of the order Monstrilloida in the Gulf of California. The present discovery in deep oceanic waters significantly adds to our knowledge of the habitat range of this copepod order and likely anticipate further interesting findings of monstrilloids in deep waters worldwide.

Keywords: Parasitic copepods; Taxonomy; Sledge; Zooplankton; Monstrillids

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Una especie nueva del género Monstrilla (Copepoda: Monstrilloida: Monstrillidae)

del golfo de California, México

Resumen

Con base en muestras biológicas de aguas profundas (700-750 m) obtenidas del sur del golfo de California, costa del Pacífico de México, se describe una especie nueva del género Monstrilla Dana, 1849 con base en una hembra preadulta recolectada con un trineo epibentónico. Monstrilla hendrickxi sp. n. se distingue por una combinación única de caracteres que incluyen: 1) ausencia de estructuras oculares; 2) anténulas robustas, con los segmentos 2-4 parcialmente fusionados; 3) anténula con elementos apicales muy desarrollados en el segmento 5 y procesos espiniformes en los segmentos 2-5; y 4) quinta pata bilobulada, lóbulo exopodal armado con 2 setas apicales, lóbulo endopodal digitiforme, desarmado. La nueva especie tiene afinidad con congéneres de superficie que tienen lóbulos exopodales armados con 2 setas. Este es el quinto registro de monstriloides en el golfo de California. El presente hallazgo aumenta significativamente nuestro conocimiento sobre el intervalo de hábitats de este orden de copépodos y probablemente anticipa más descubrimientos interesantes de monstriloides en aguas profundas de todo el mundo.

Palabras clave: Copépodos parásitos; Taxonomía; Trineo colector; Zooplancton; Monstrílidos

Introduction

Members of the copepod order Monstrilloida Sars, 1901 are, as larvae, endoparasites of benthic marine invertebrates, but their infective early nauplii and their non-feeding reproductive adult and preadult stages are planktonic. The known hosts of the postnaupliar and juvenile stages include benthic polychaetes (species of the families Syllidae, Capitellidae, Serpulidae, and Spionidae), mollusks, and sponges (Huys et al., 2007; Jeon et al., 2018; Suárez-Morales, 2011, 2018; Suárez-Morales et al., 2010, 2014). In plankton, monstrilloids have been reported chiefly from a wide range of shallow coastal habitats including estuaries (Suárez-Morales et al., 2020), coastal embayments (Suárez-Morales, 1994a, b; Suárez-Morales & Gasca, 1990), and coral reefs (Sale et al., 1996), where they can be found in aggregations (Suárez-Morales, 2001). Monstrilloids have been recently reported from rocky shore tidepools as well (Cruz-Lopes de Rosa et al., 2021). Deep oceanic waters, though, would seem to be an unlikely source of monstrilloid specimens for taxonomic study because of the copepods’ limited dispersal capacity in the water column and their need to remain close to their benthic hosts (Suárez-Morales, 2001, 2011, 2018).

The order is currently represented by a single family Monstrillidae Dana, 1849 containing at least 7 valid genera: Monstrilla Dana, 1849; Cymbasoma Thompson, 1888; Monstrillopsis Sars, 1921; Maemonstrilla Grygier & Ohtsuka, 2008; Australomonstrillopsis Suárez-Morales & McKinnon, 2014; Caromiobenella Jeon, Lee & Soh, 2018, and Spinomonstrilla Suárez-Morales, 2019 (Jeon et al., 2016, 2018; Suárez-Morales et al., 2020). Currently, the genus Cymbasoma, with 78 nominal species, is the most diverse within the order (Razouls et al., 2023: Suárez-Morales & McKinnon, 2016; Walter & Boxshall, 2022). The taxonomic examination of a monstrilloid subadult female collected with a deep-water epibenthic sledge operated close to the bottom within a depth range of 700-750 m in oceanic waters of the southern Gulf of California, Mexico, allowed us to recognize this individual as representative of an undescribed species of Monstrilla, which is herein described following upgraded morphological standards and compared with congeneric species (Grygier & Ohtsuka, 1995). This is the third published record of monstrilloid copepods from deep oceanic waters worldwide (see Suárez-Morales & Mercado-Salas, 2023) and the fifth record of monstrilloids in the Gulf of California.

Materials and methods

A subadult female of a monstrilloid copepod was collected with an epibenthic sledge operated in mid-water, close to the bottom off the Pacific coast of northwestern Mexico, in the Gulf of California. The maximum sampling depth was 750 m. Immediately after collection, the organisms from the haul were preserved in 4% formalin with seawater. Sorting of specimens and preliminary observations were made under an Olympus SZ51 stereomicroscope. The single female monstrilloid individual thus found was recognized as a subadult female and tentatively identified as a member of the genus Monstrilla. Further examination was performed under an Olympus BX51 compound microscope with Nomarski DIC optics. Prior to examination, the specimen was partially dissected and swimming legs 1-4 and the cephalothorax, urosome +antennules were mounted in glycerol on glass slides, which were sealed with acrylic nail varnish. The slides have been deposited in the collection of Zooplankton (ECO-CHZ) held at El Colegio de la Frontera Sur (ECOSUR), Unidad Chetumal, in Chetumal, Quintana Roo, Mexico (ECO-CH-Z). Detailed examination allowed us to determine that this specimen represented an undescribed species, which we describe herein following current descriptive standards in monstrilloid taxonomy. The general morphological terminology follows Huys and Boxshall (1991), while the nomenclature of the antennular armature follows Grygier and Ohtsuka (1995).

Description

Order Monstrilloida Sars, 1901

Family Monstrillidae Dana, 1849

Genus Monstrilla Dana, 1849

Monstrilla hendrickxi sp. nov.

(Figs. 1-4)

http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:708E6CBF-

9C0B-433B-AF6B-5D474B2490E3

Diagnosis. Large (2.9 mm) female subadult Monstrilla with robust, cylindrical cephalothorax representing about 60% of total body length and no trace of eyes. Antennules thick, about 1/3 as long as cephalothorax; antennulary segments 2-4 partly fused, segment 3 with modified setae, segments 2, 4, and 5 each furnished with a conical or spinous process. Segments 4-5 partly fused, latter segment with strongly developed apical spiniform elements. Ventral side of genital double-somite carrying short, corrugate ovigerous spines not reaching beyond distal end of caudal rami. Fifth leg bilobed, exopodal lobe bearing 2 subequally long terminal setae and endopodal lobe digitiform, unarmed. Caudal rami each with 6 setae, innermost of which (VI) shortest and outer proximal one (I) longest.

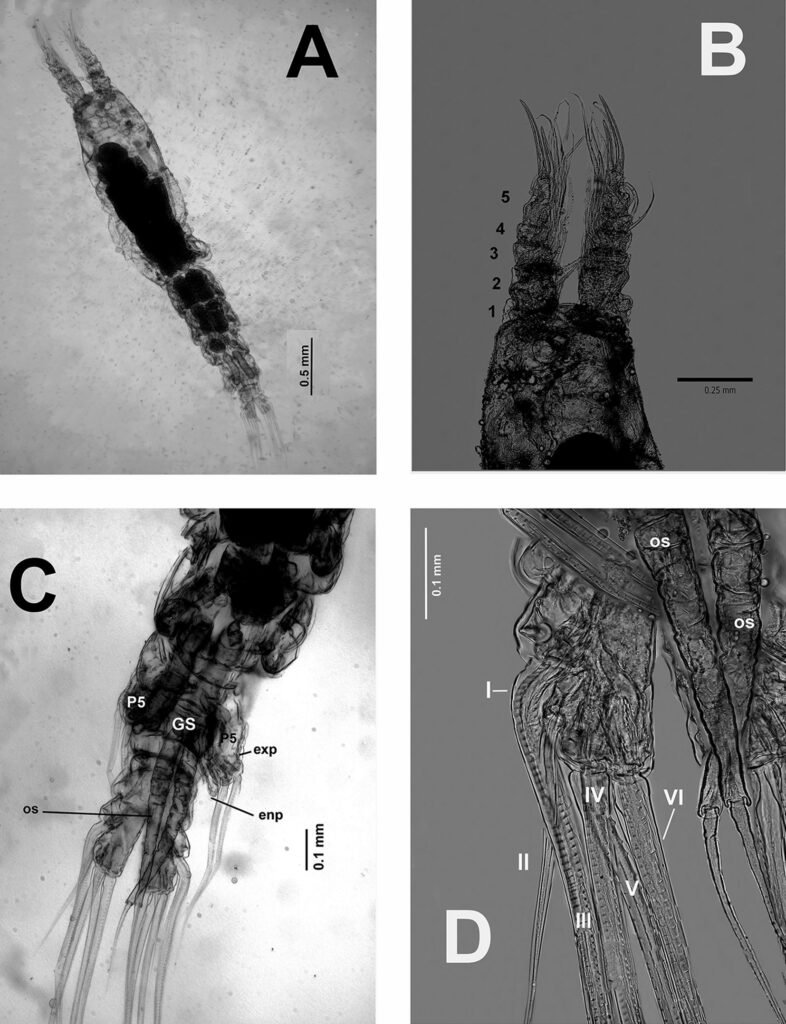

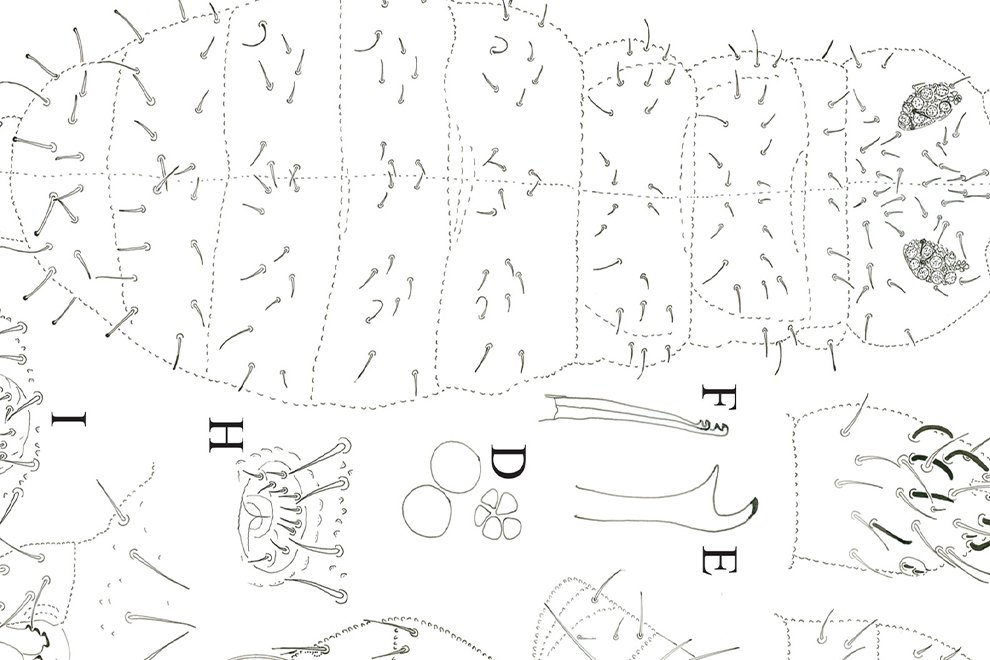

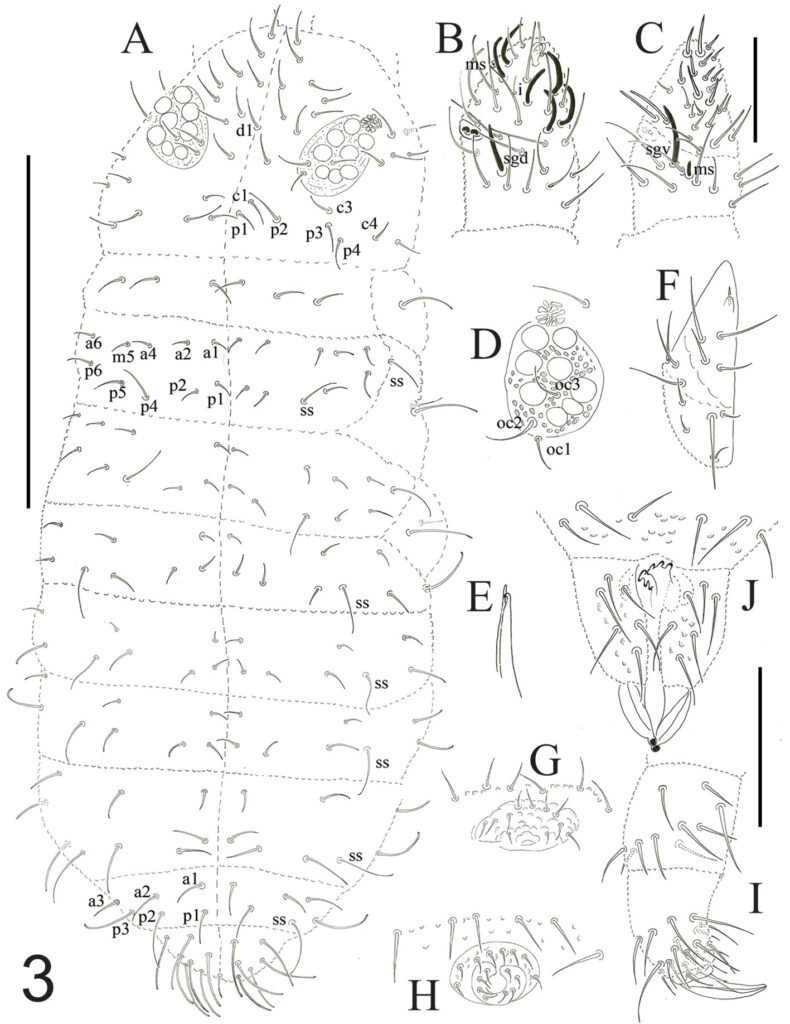

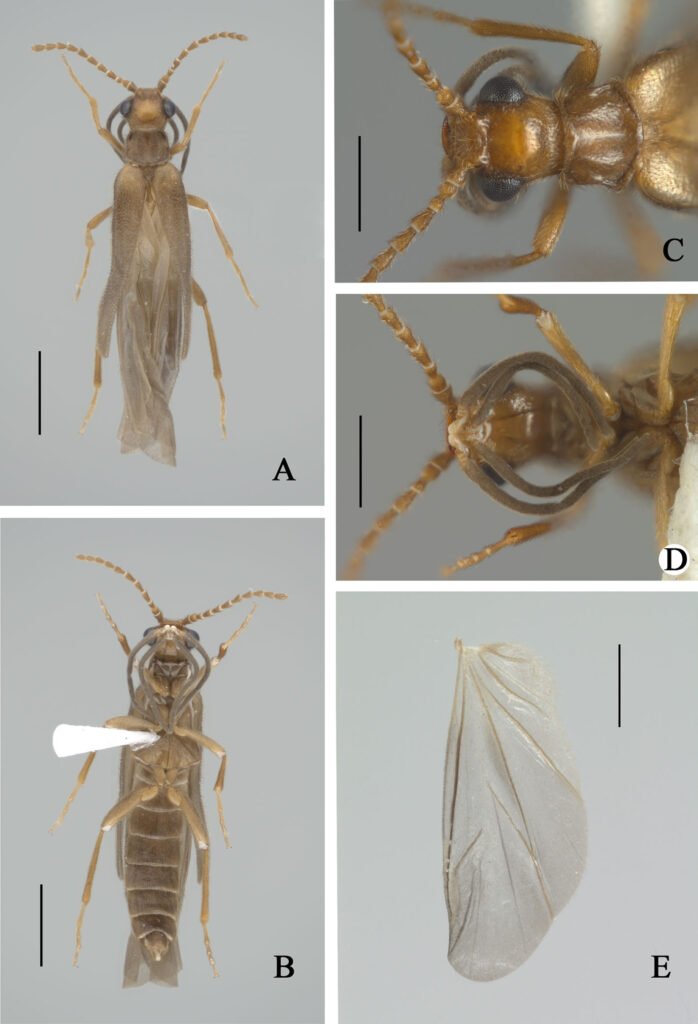

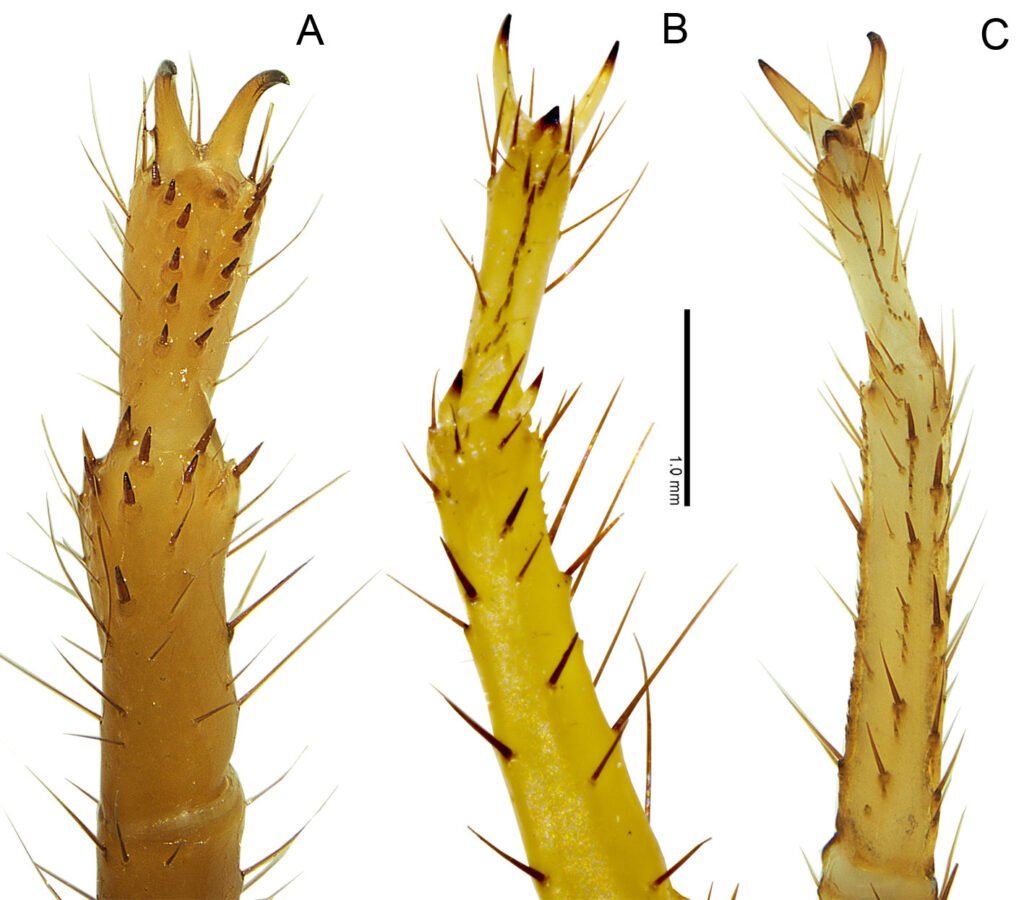

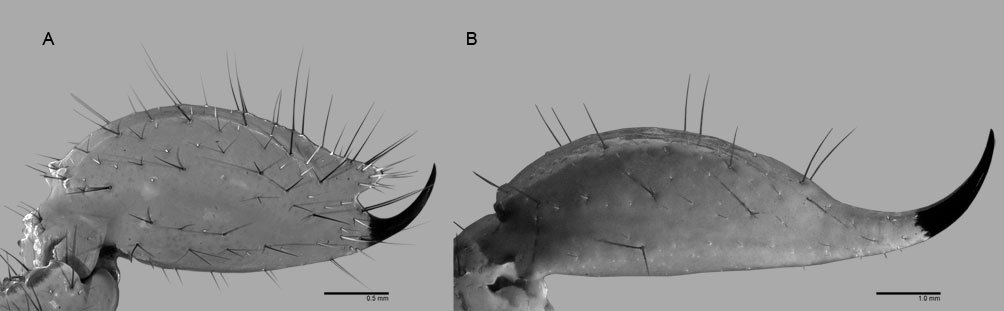

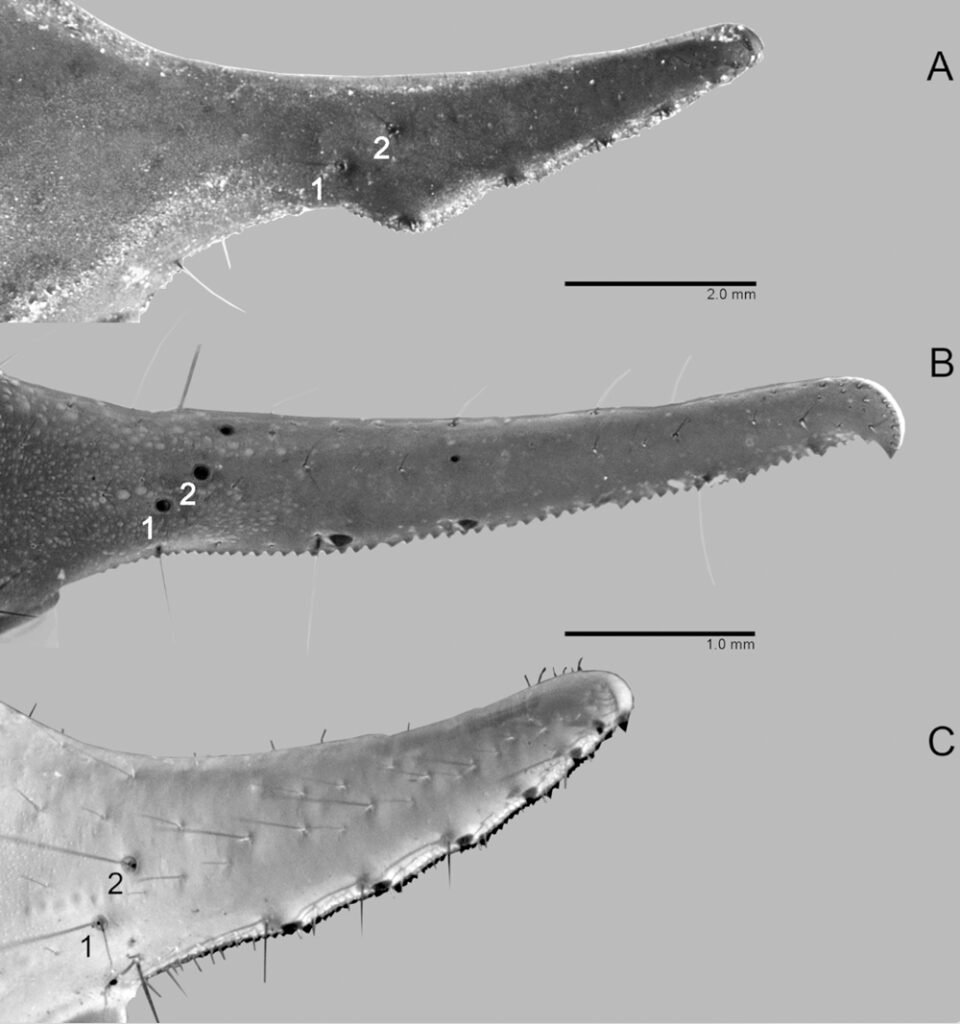

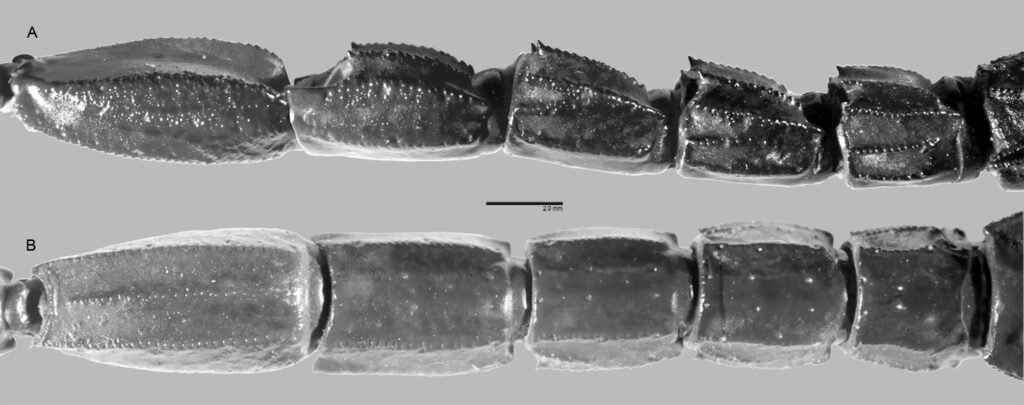

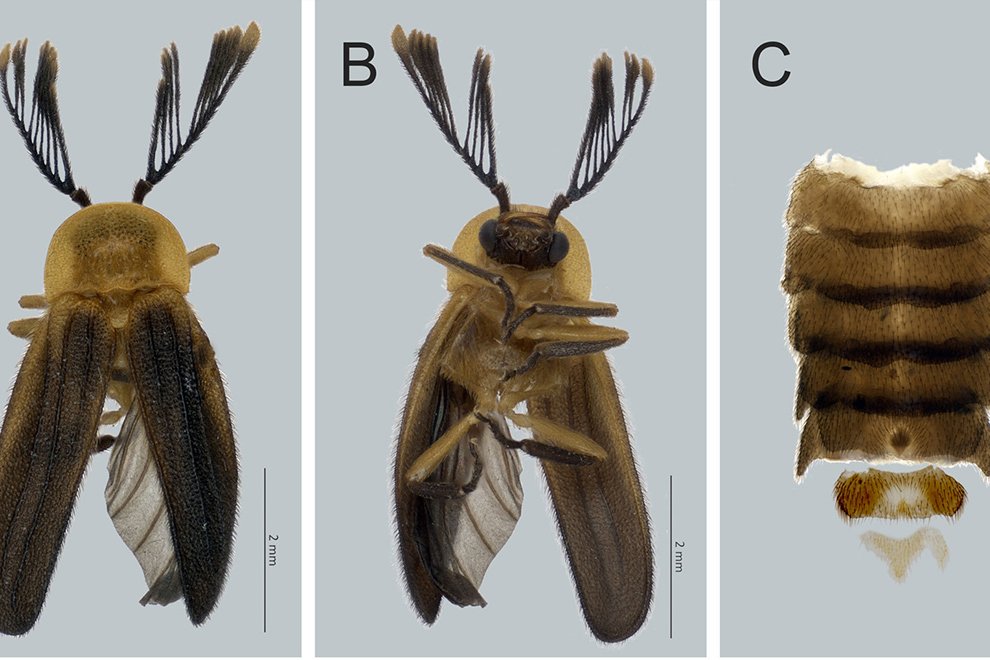

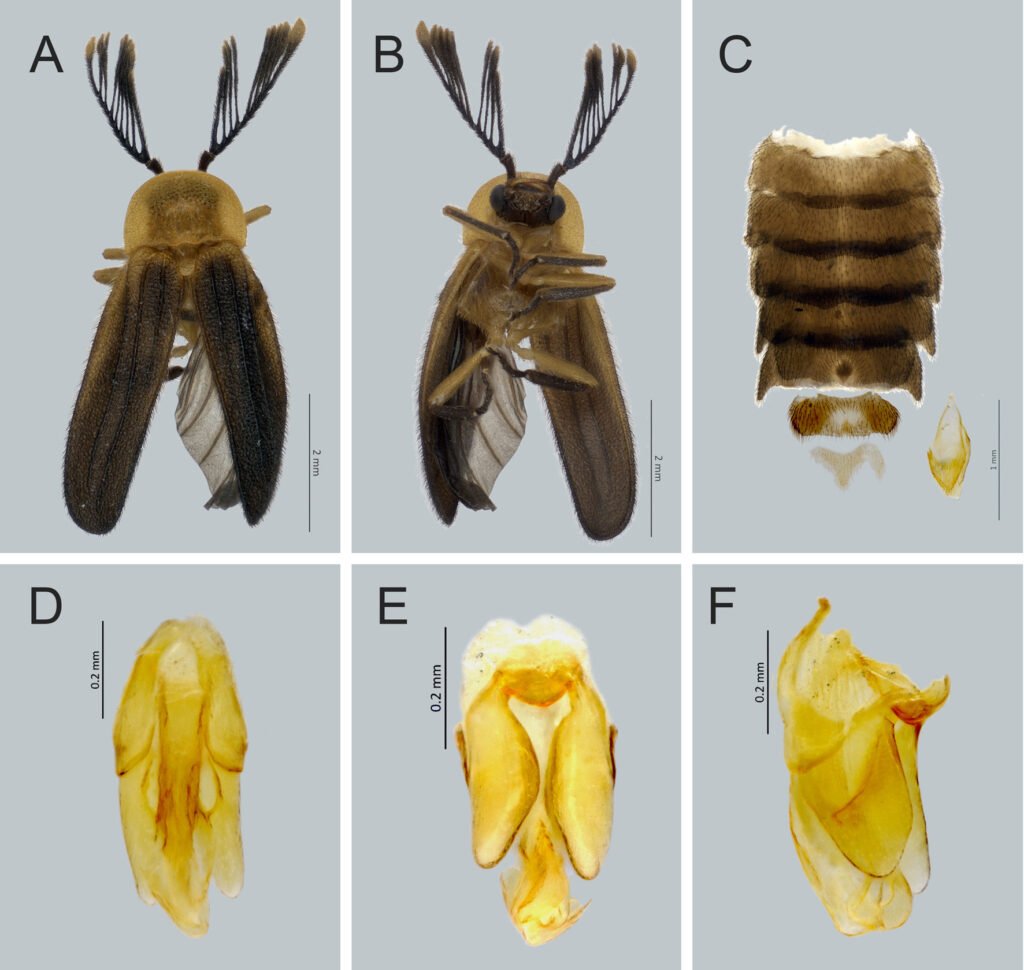

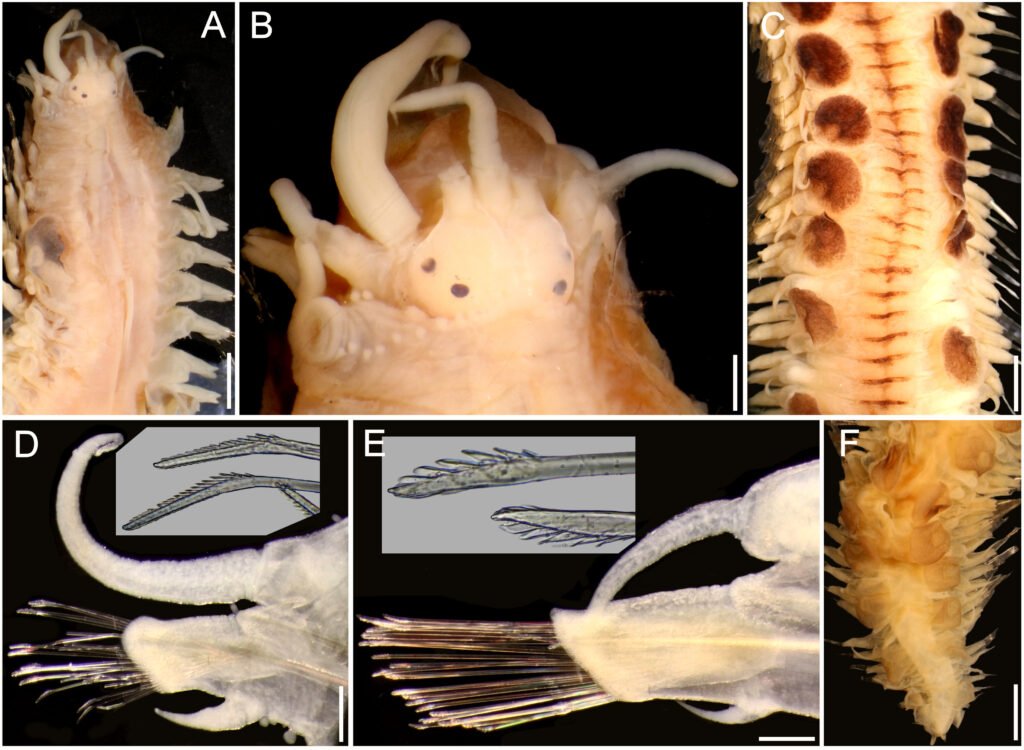

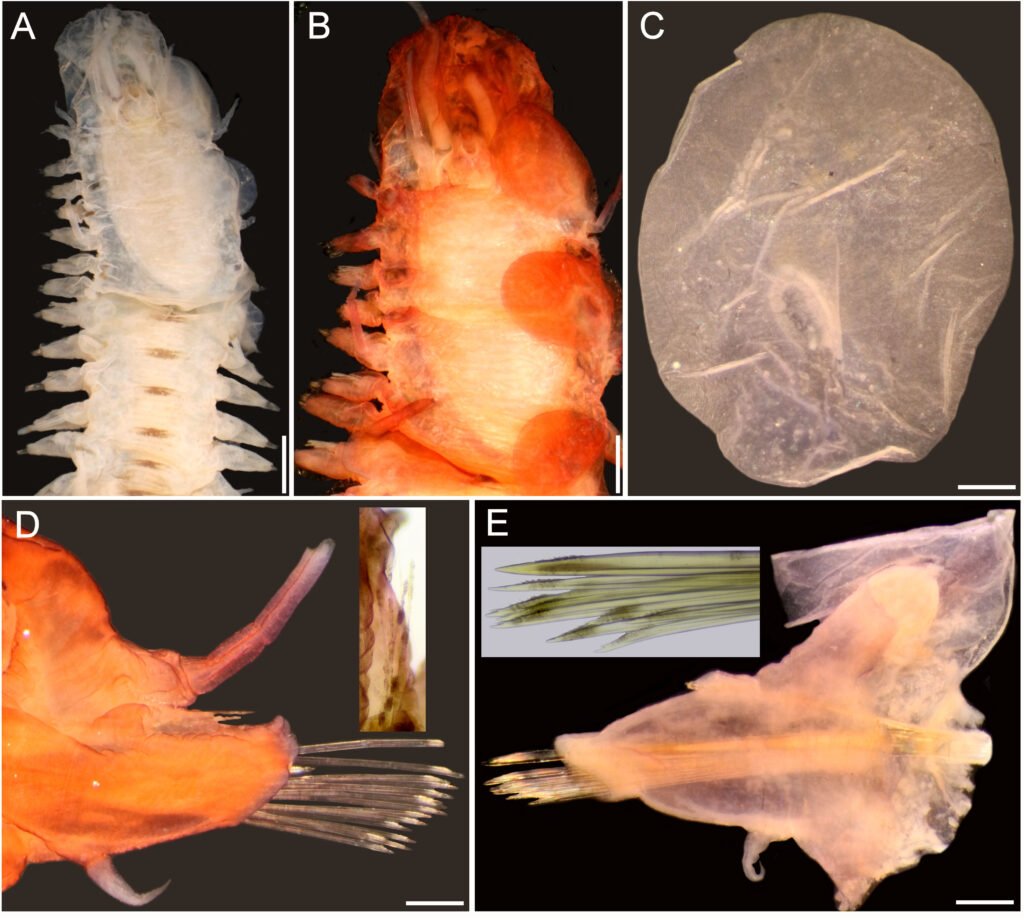

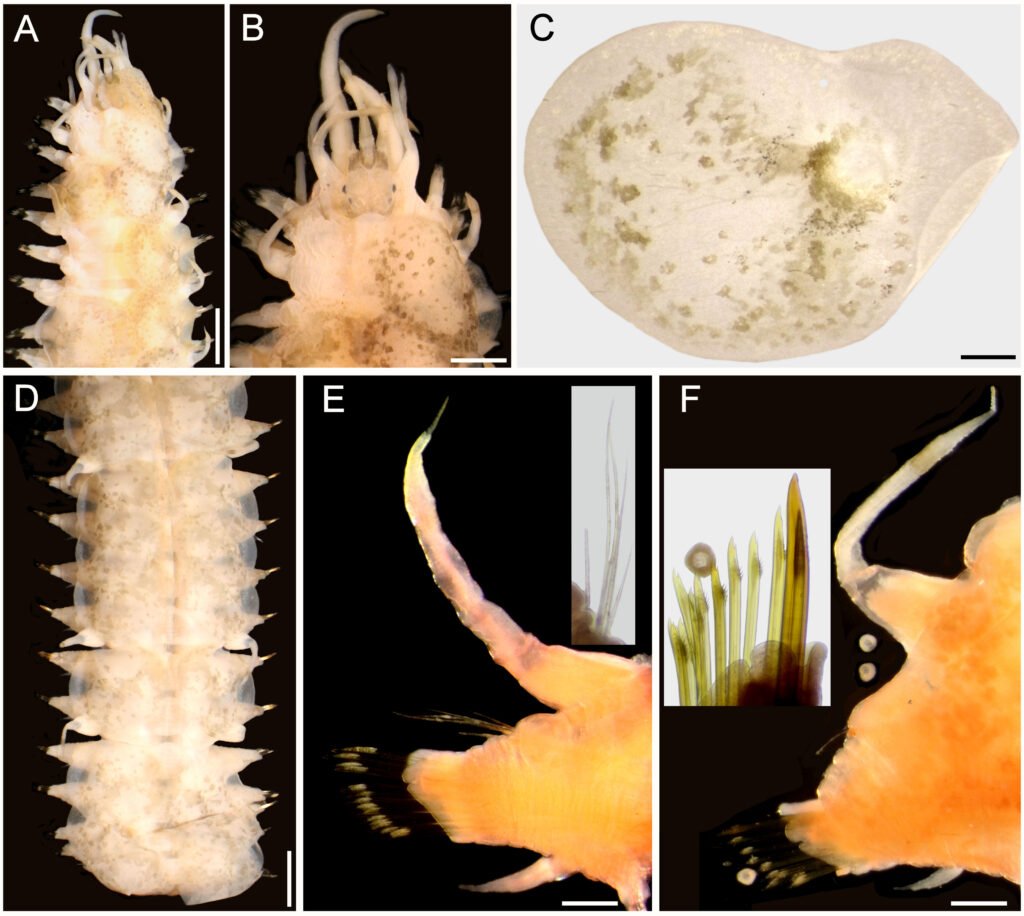

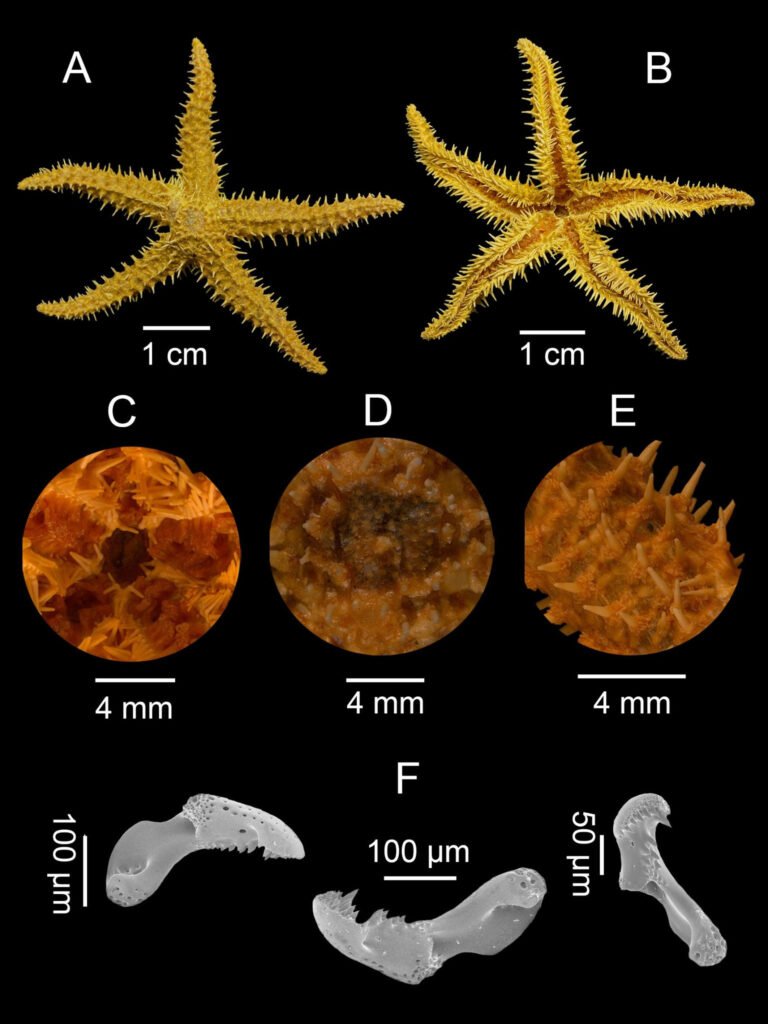

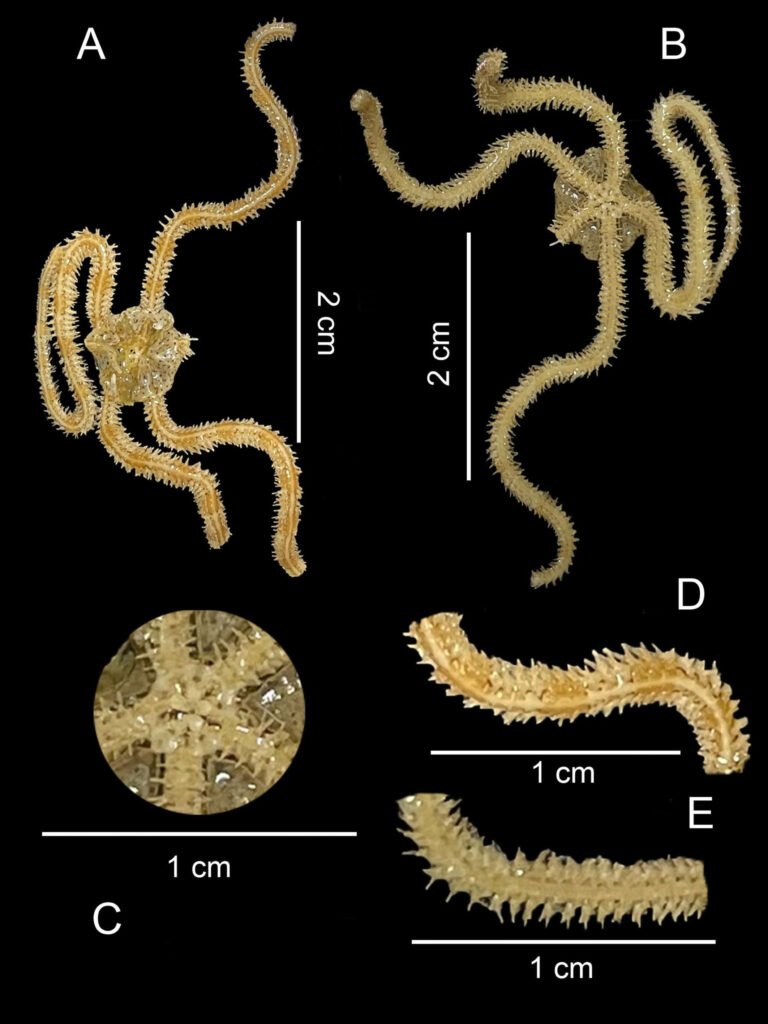

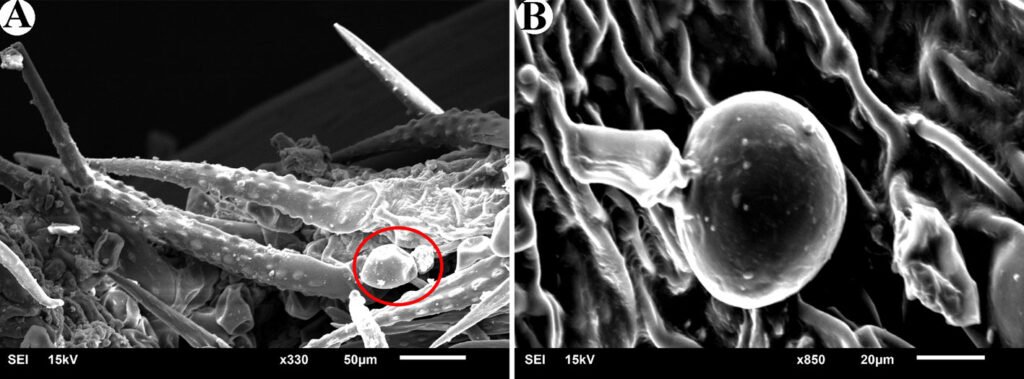

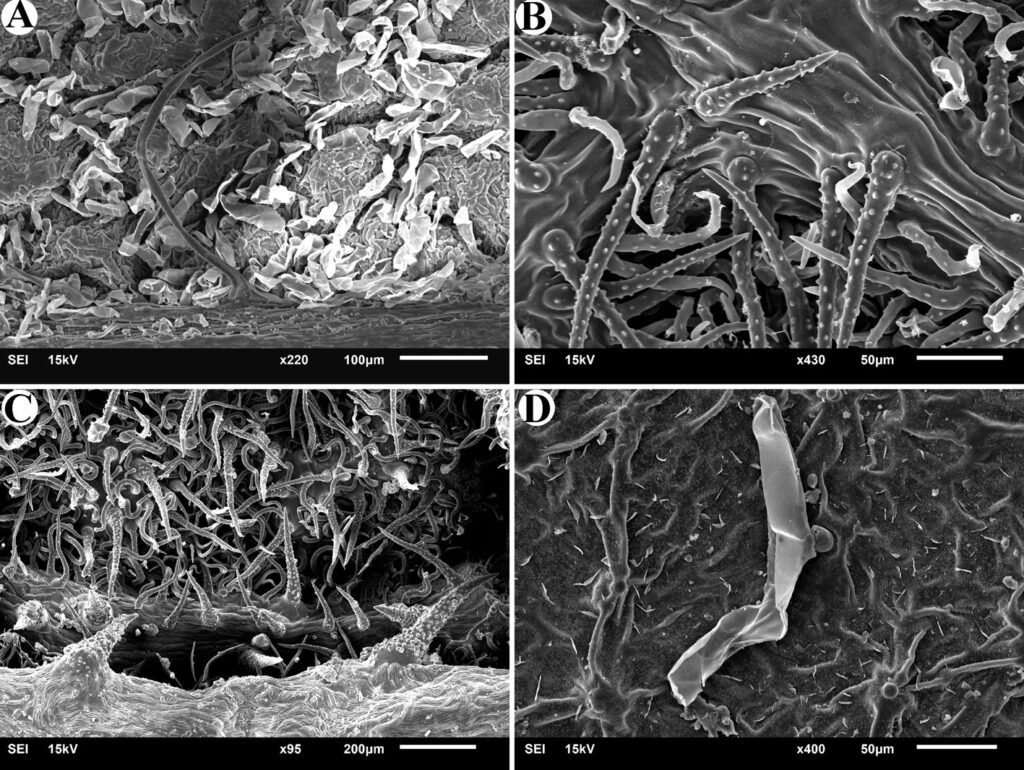

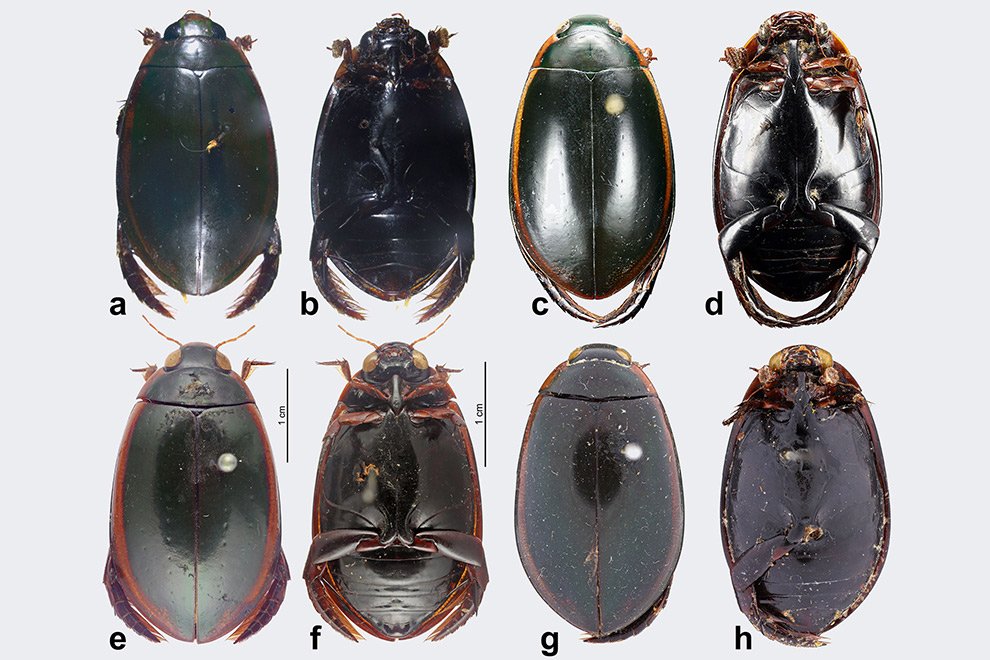

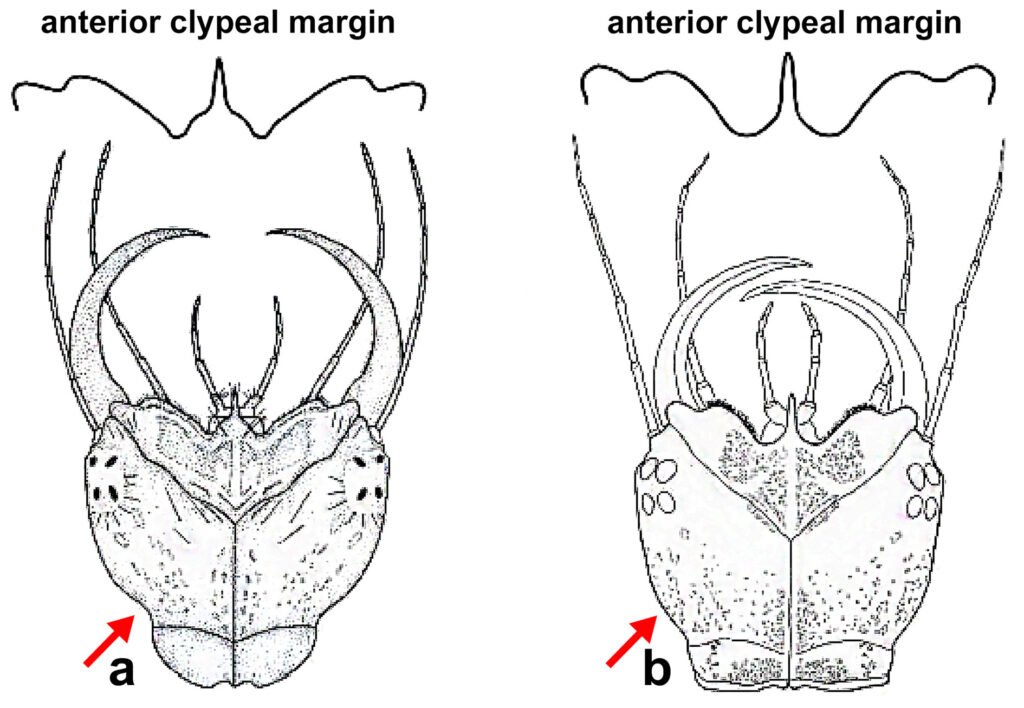

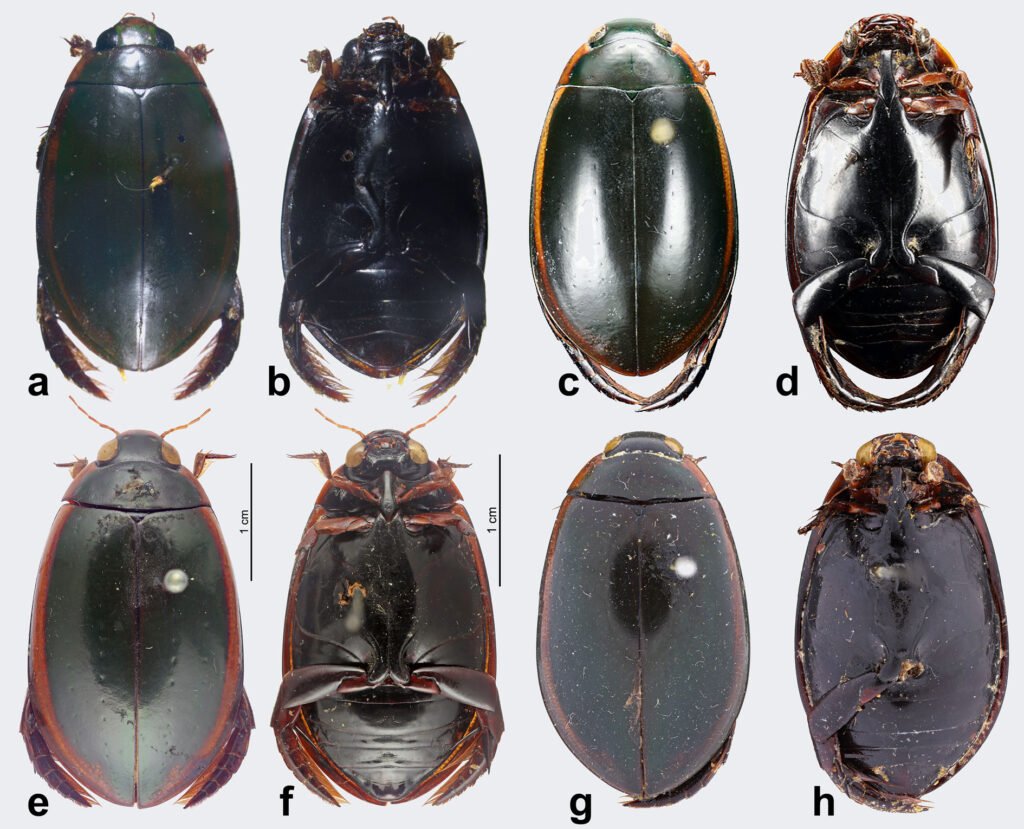

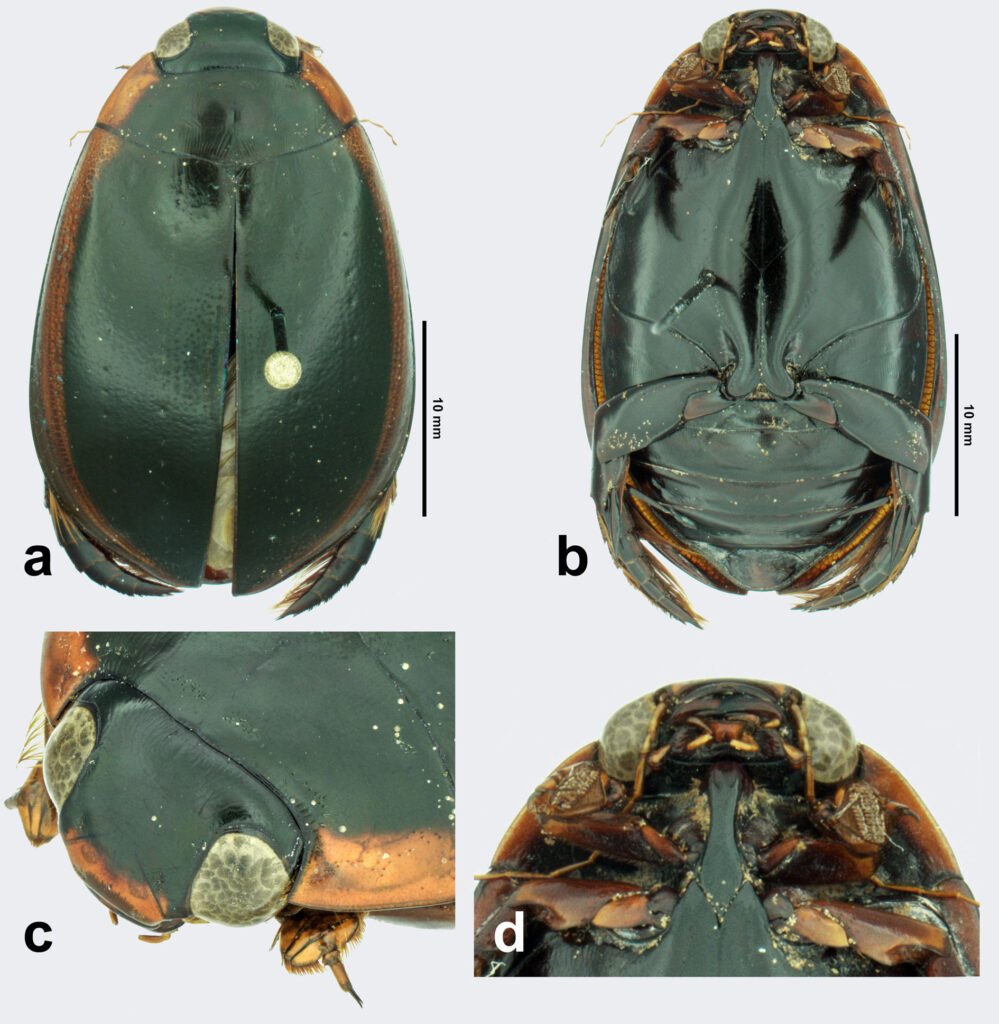

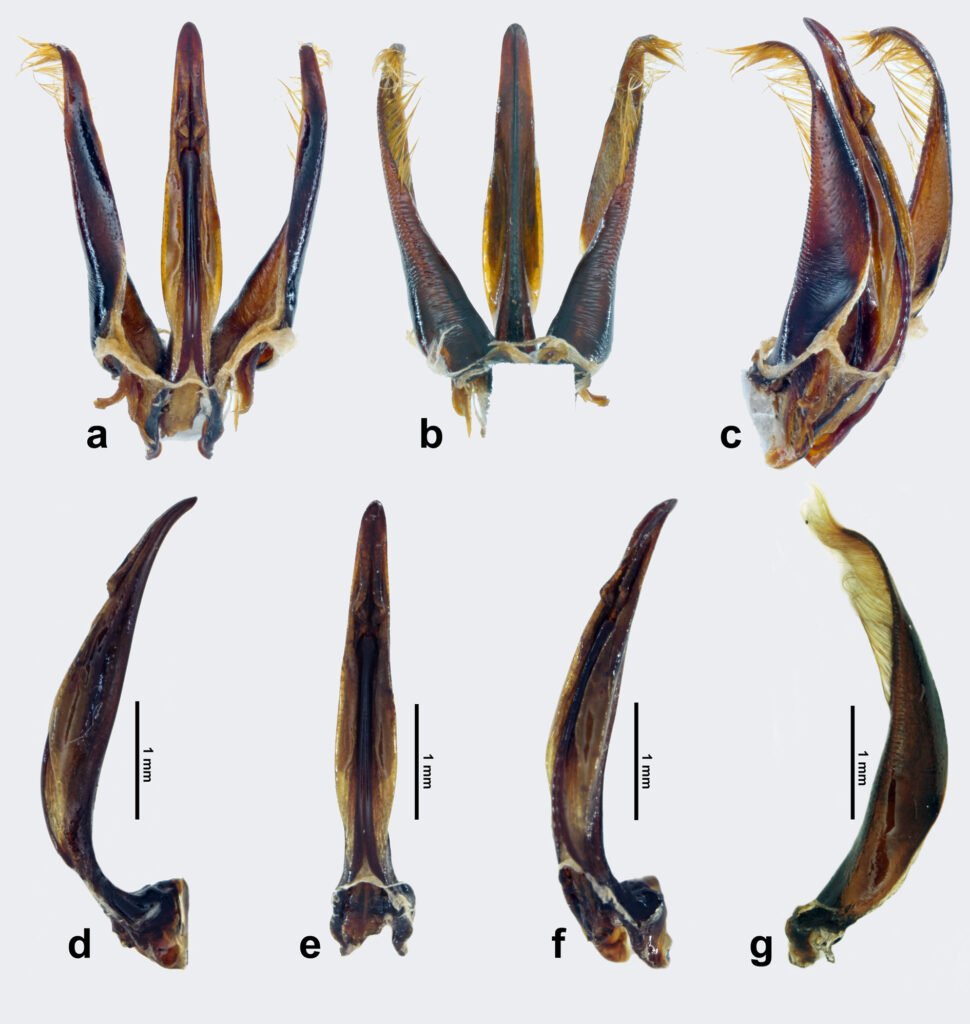

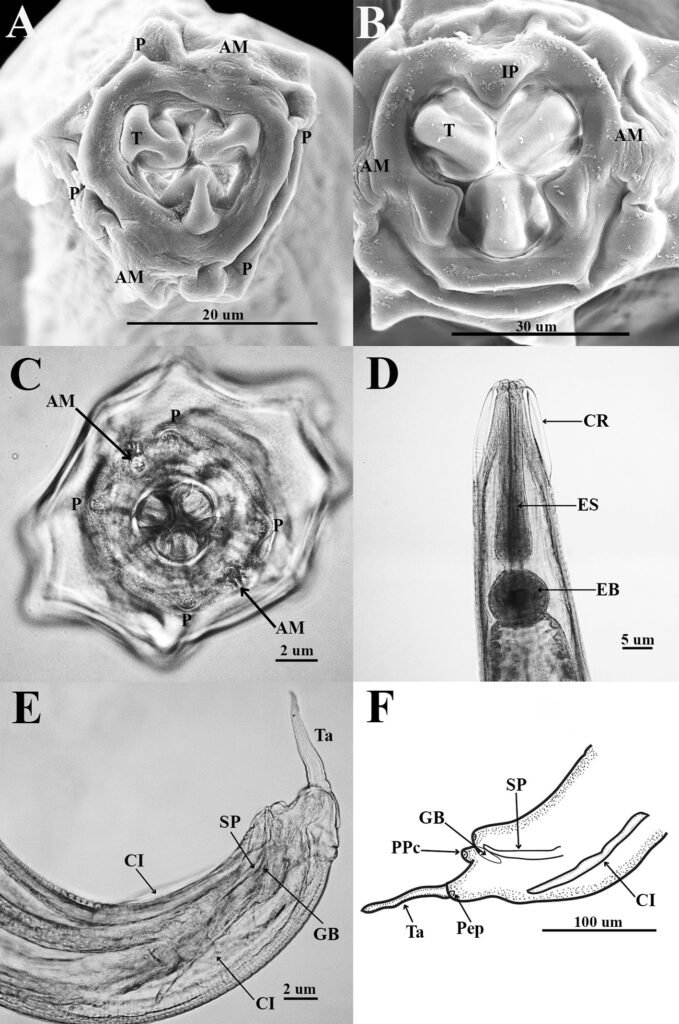

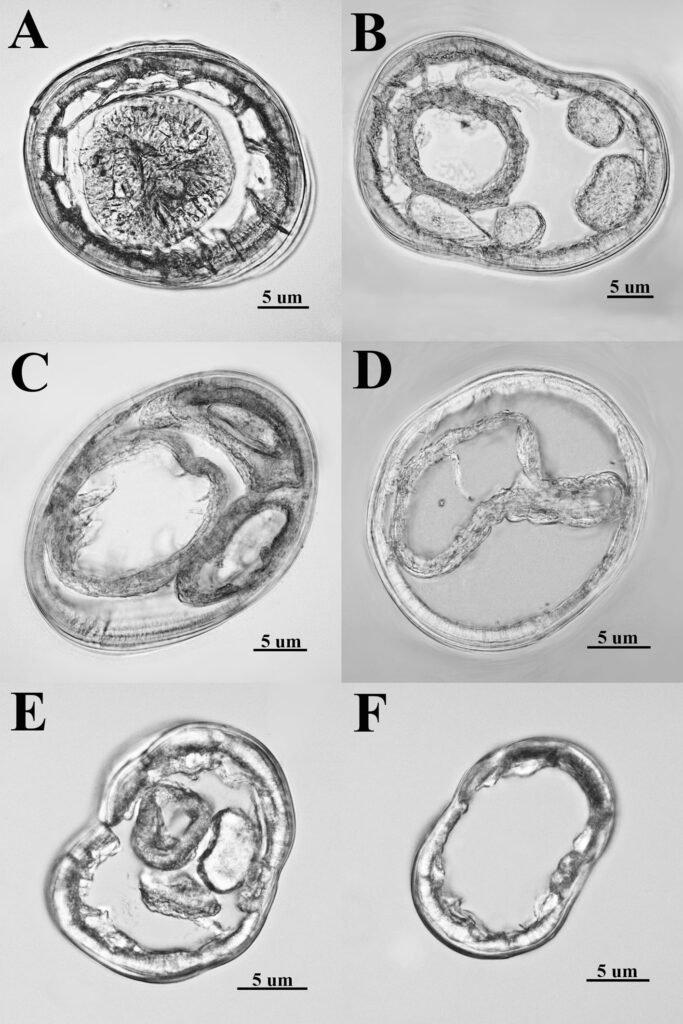

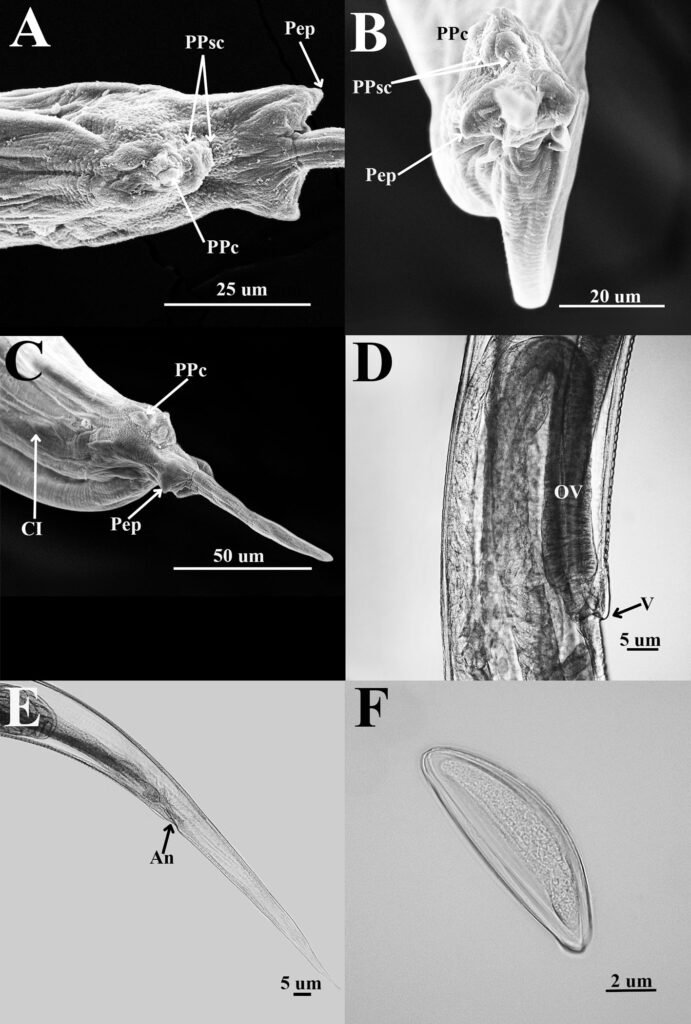

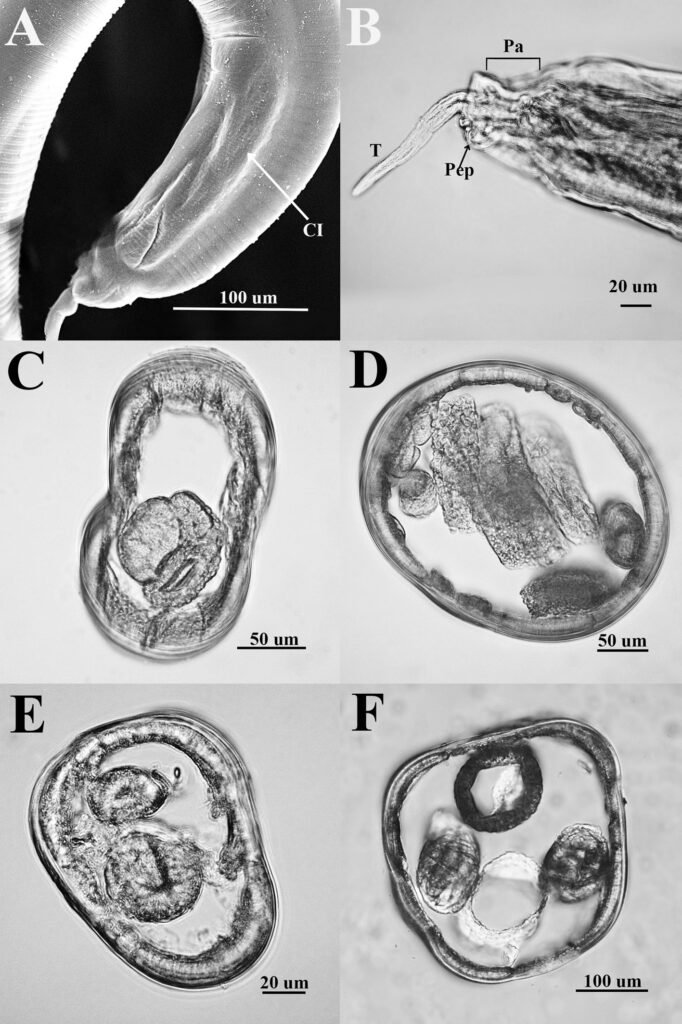

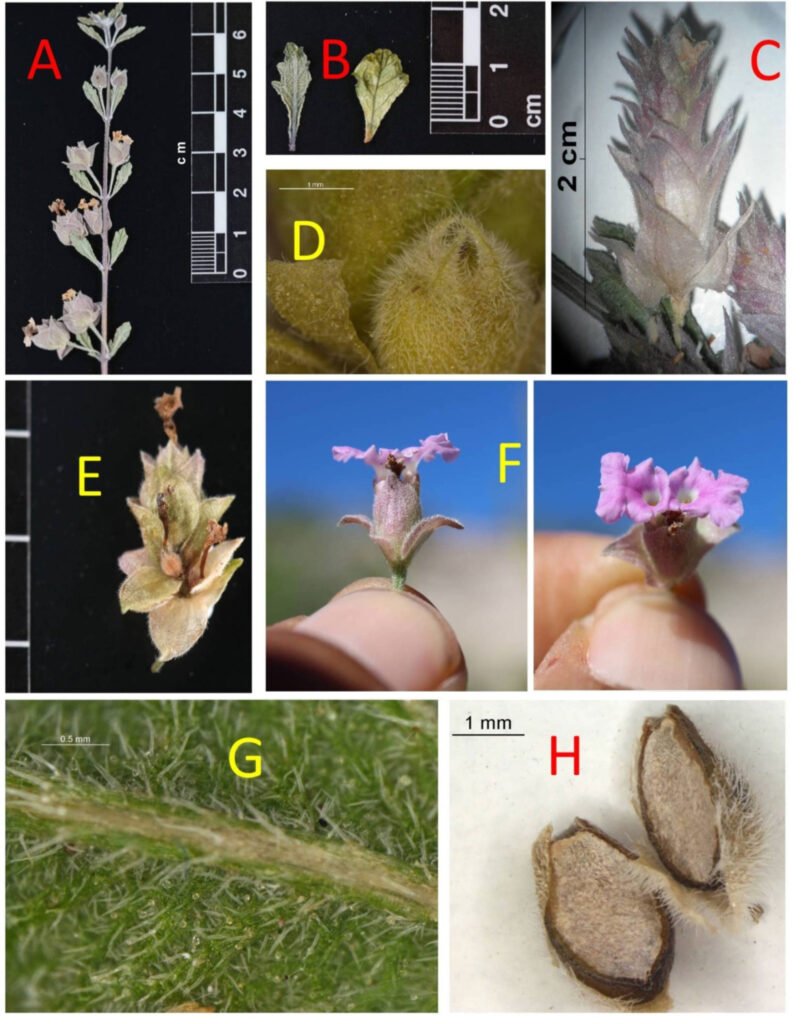

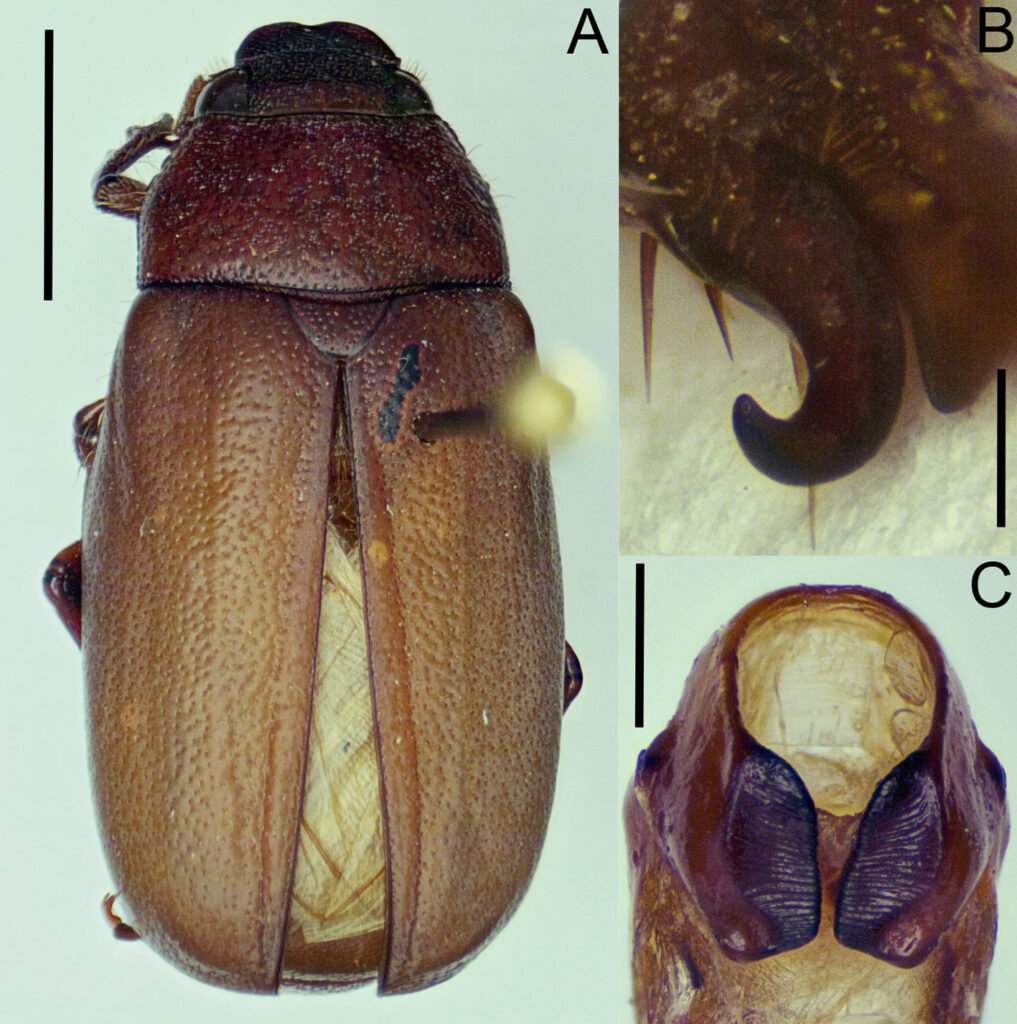

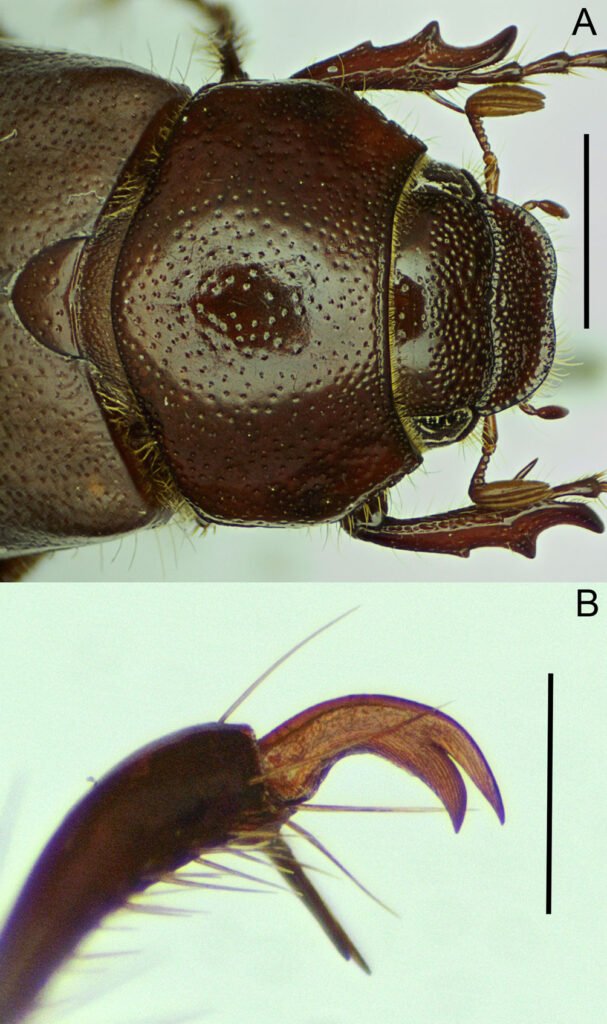

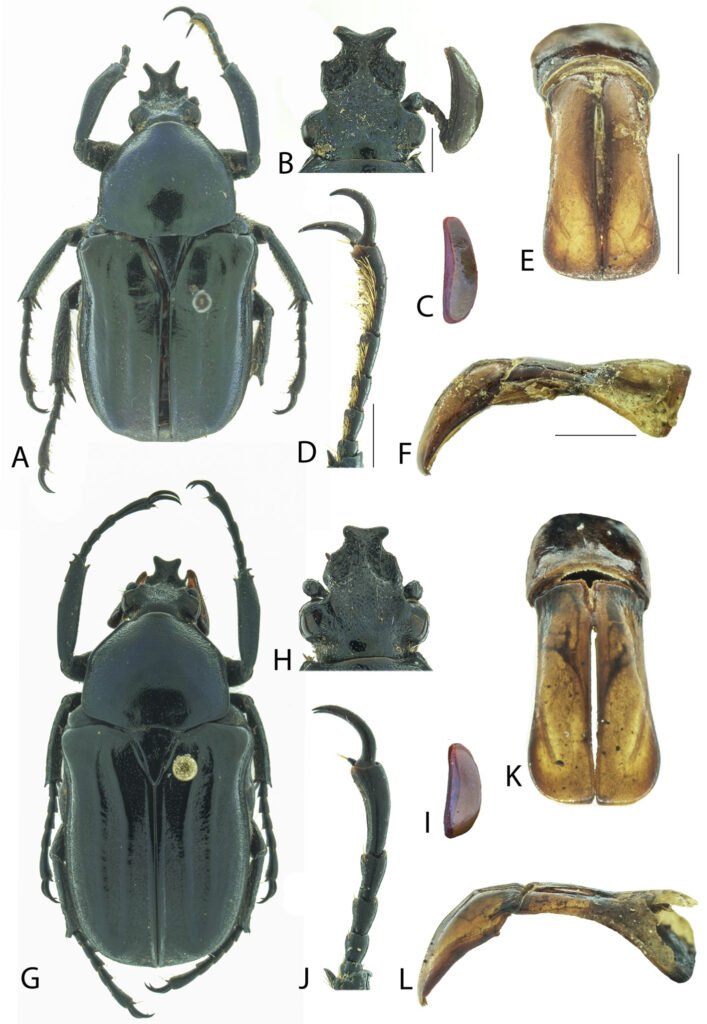

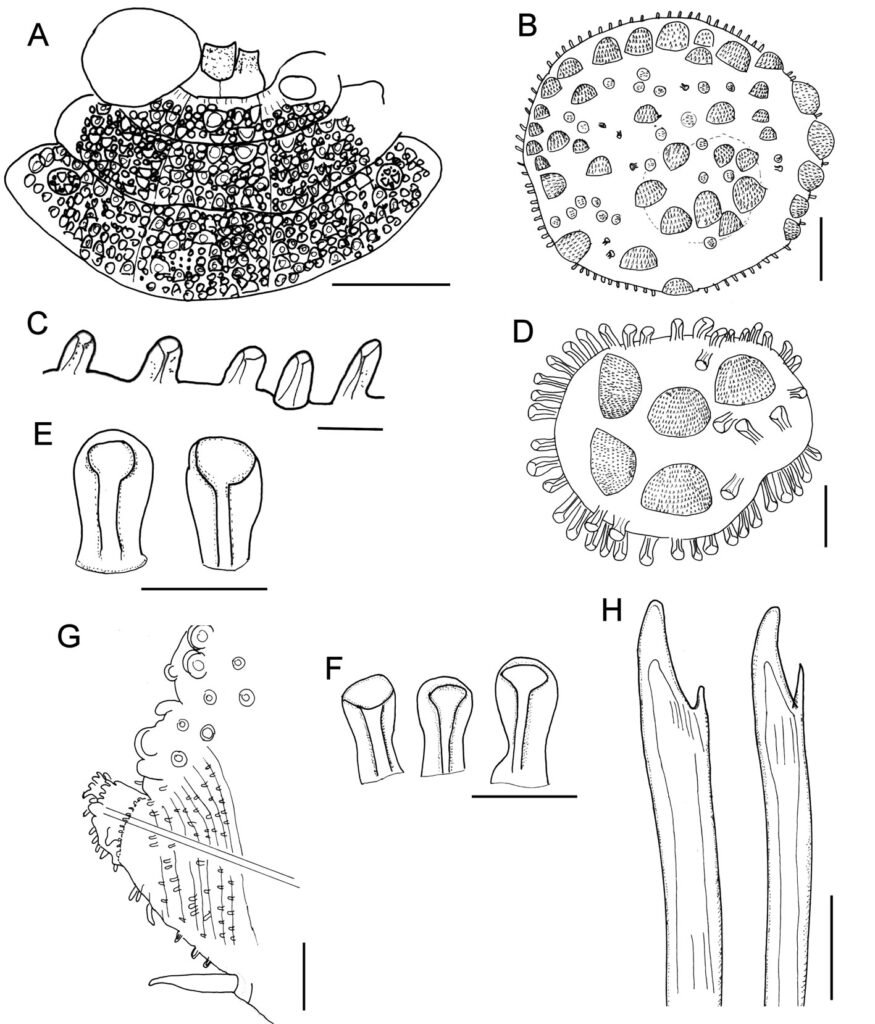

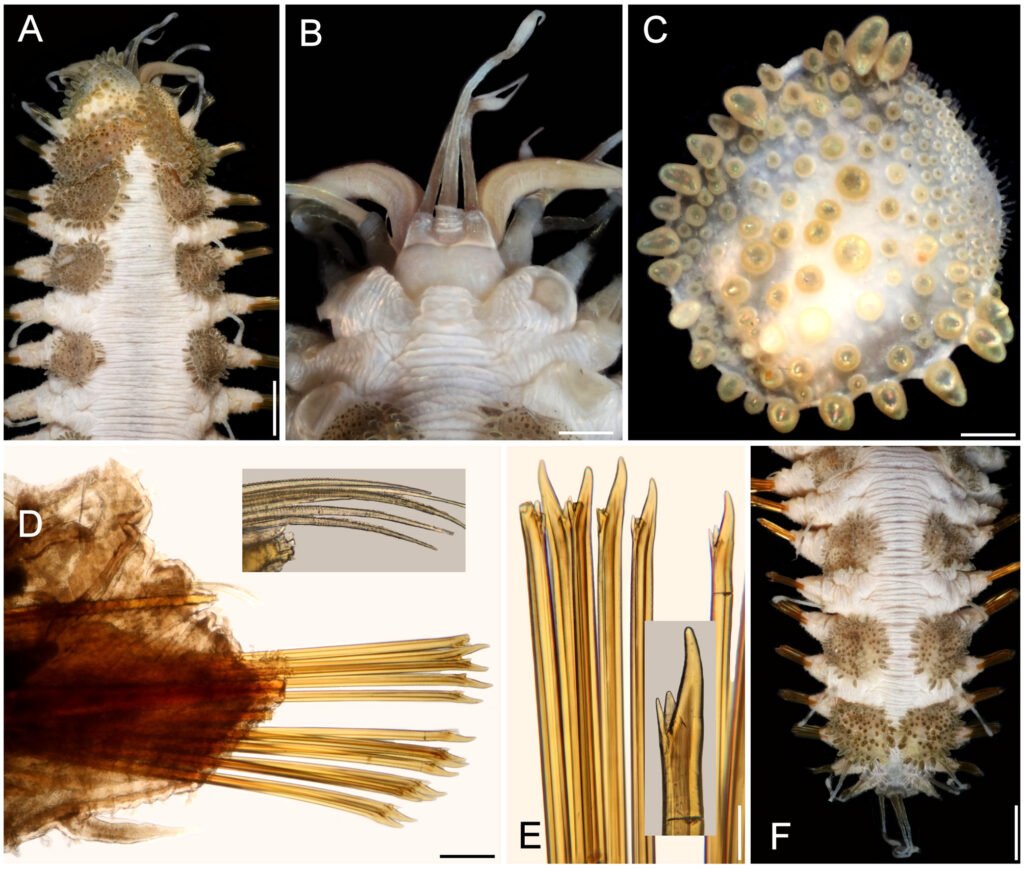

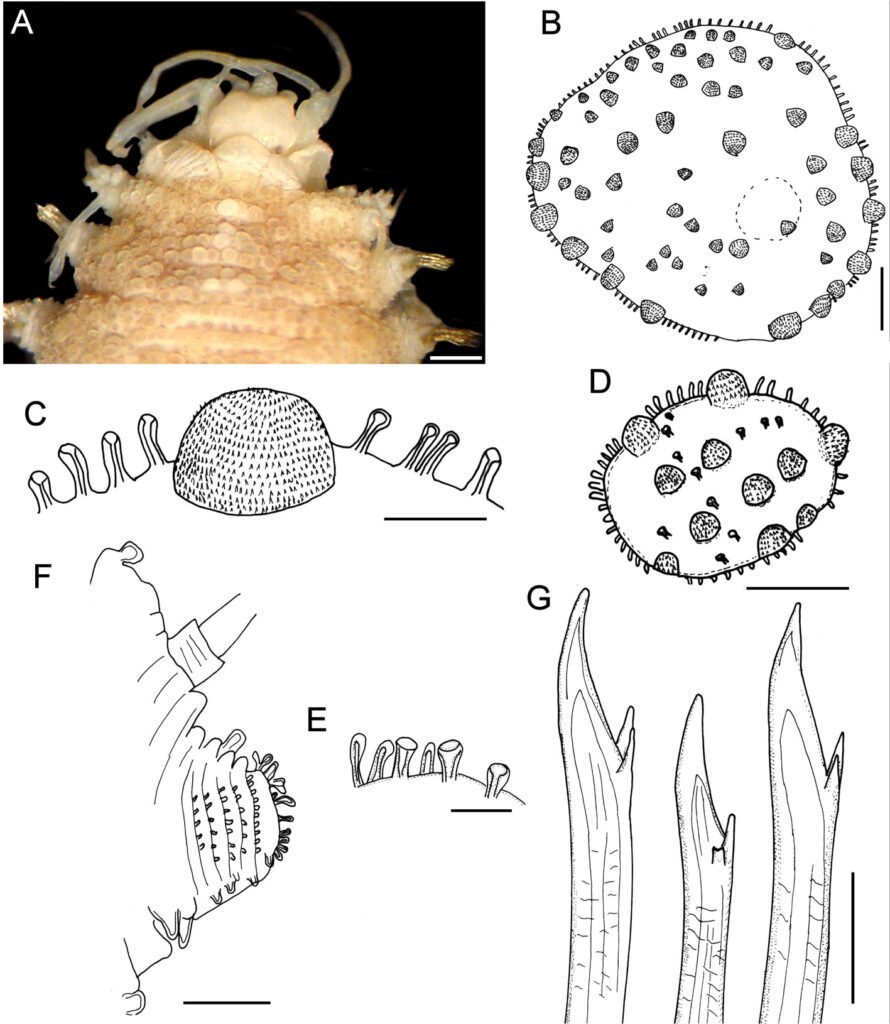

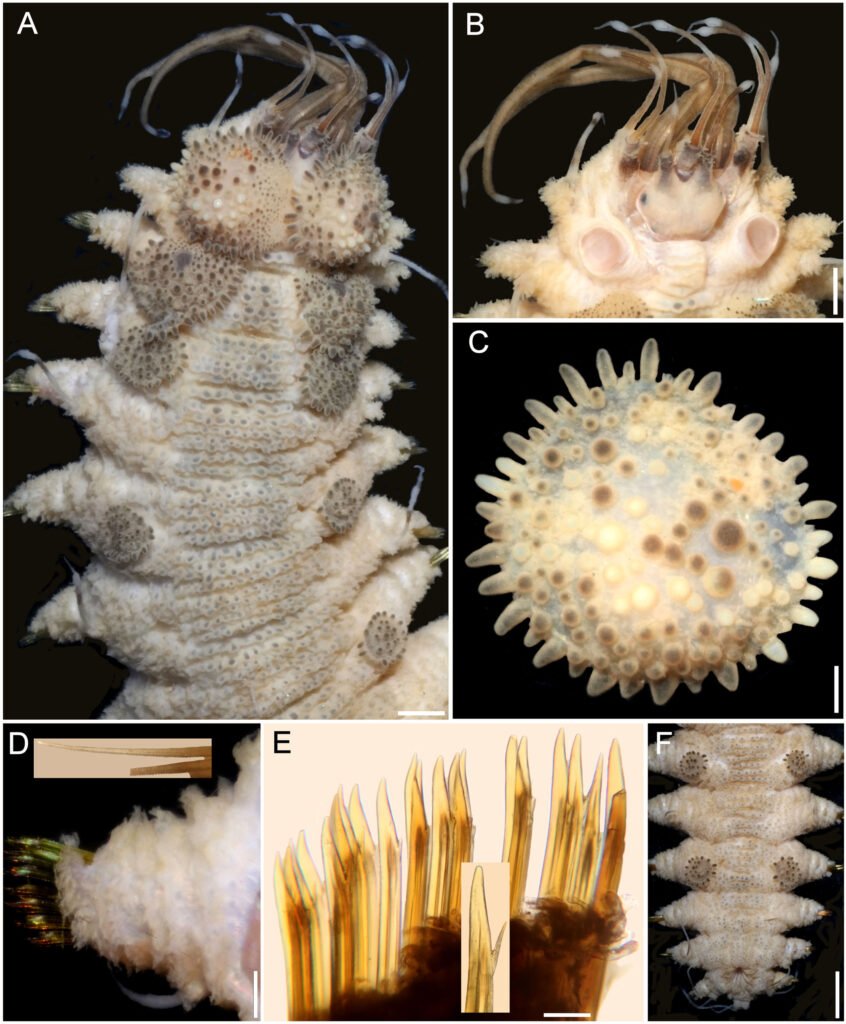

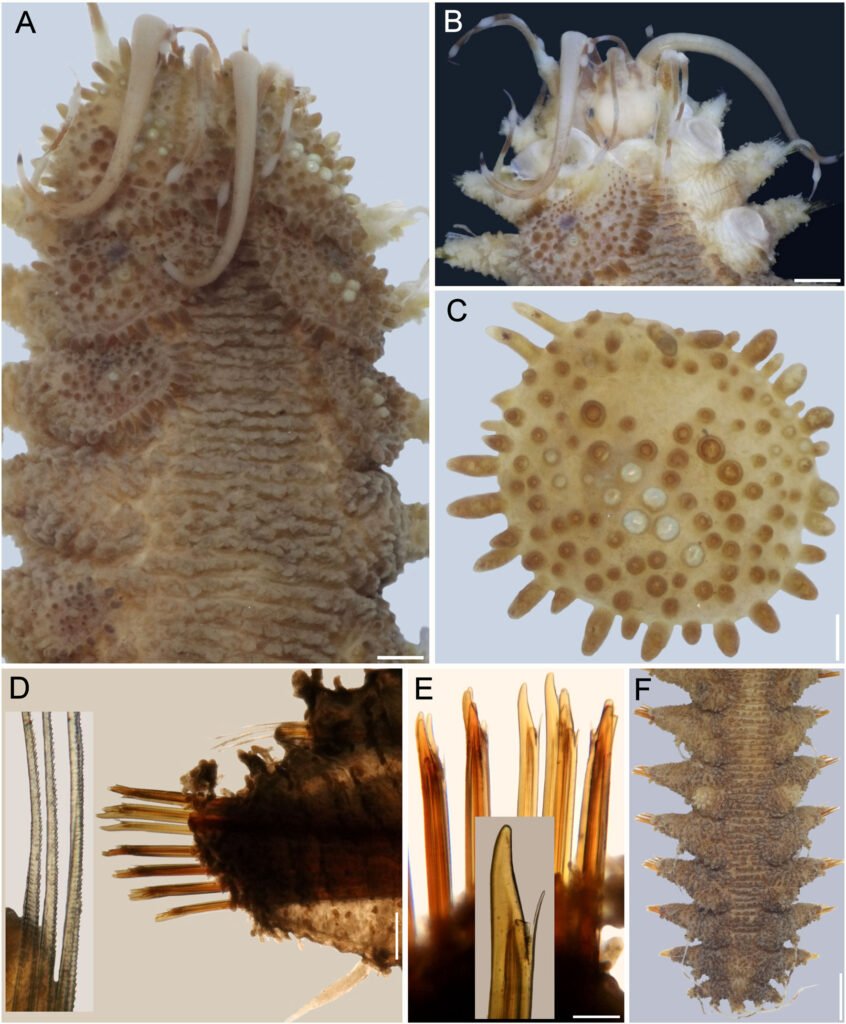

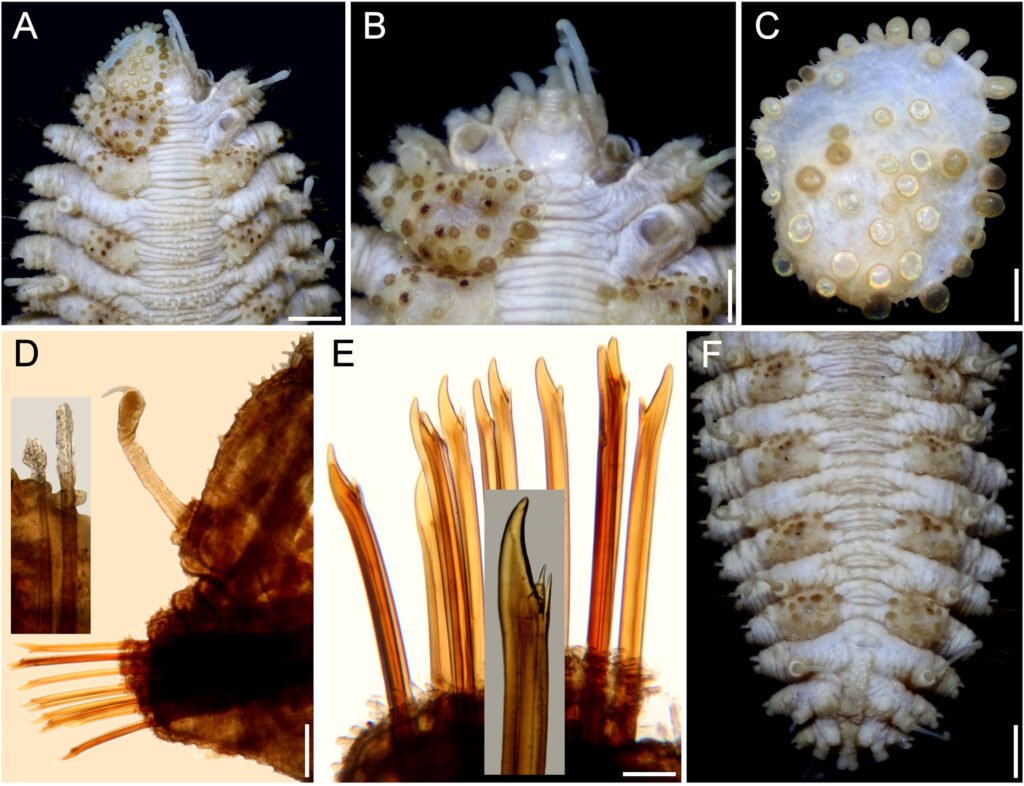

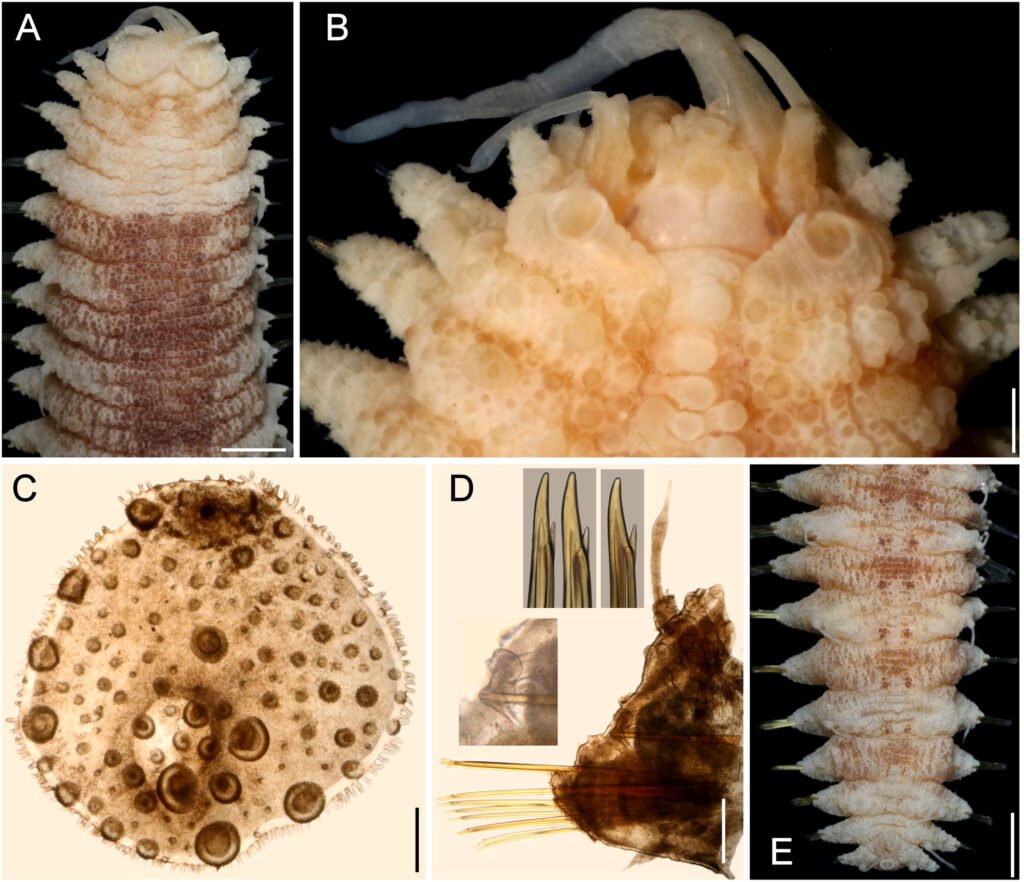

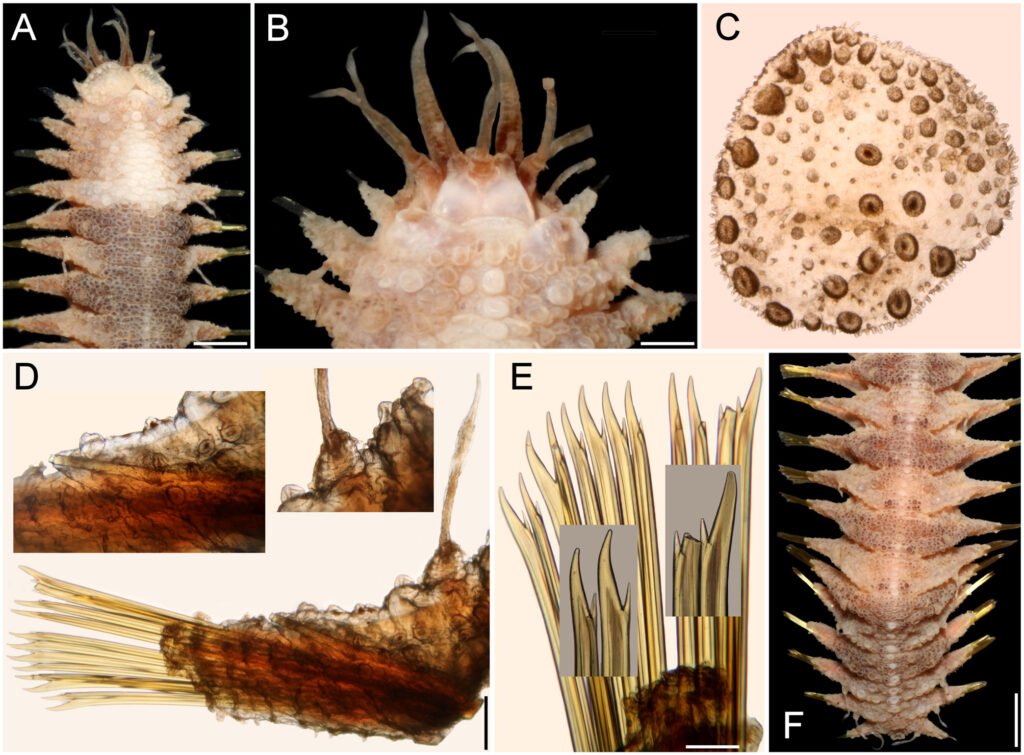

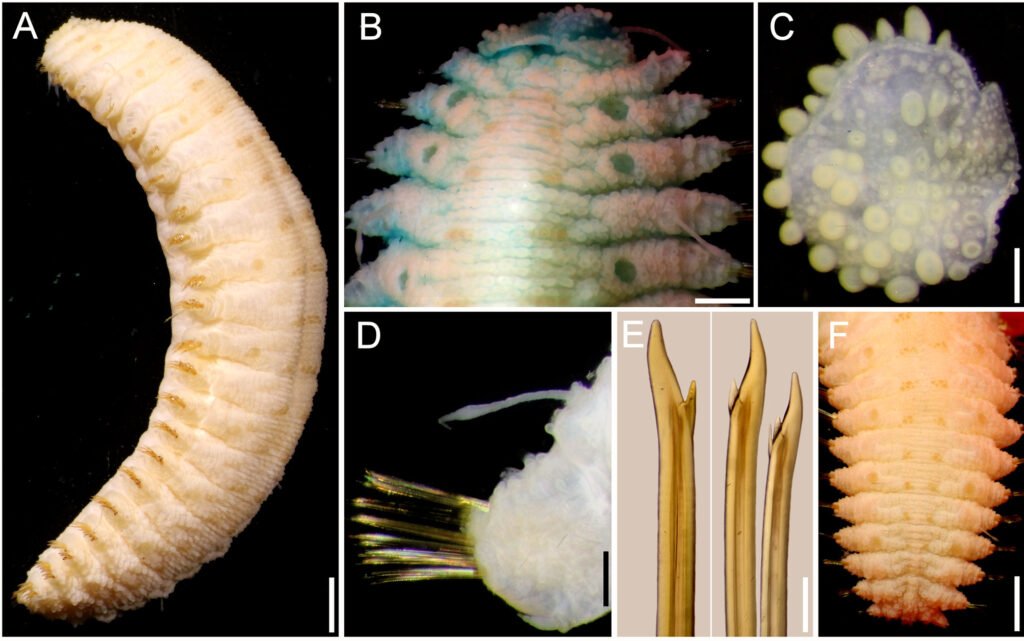

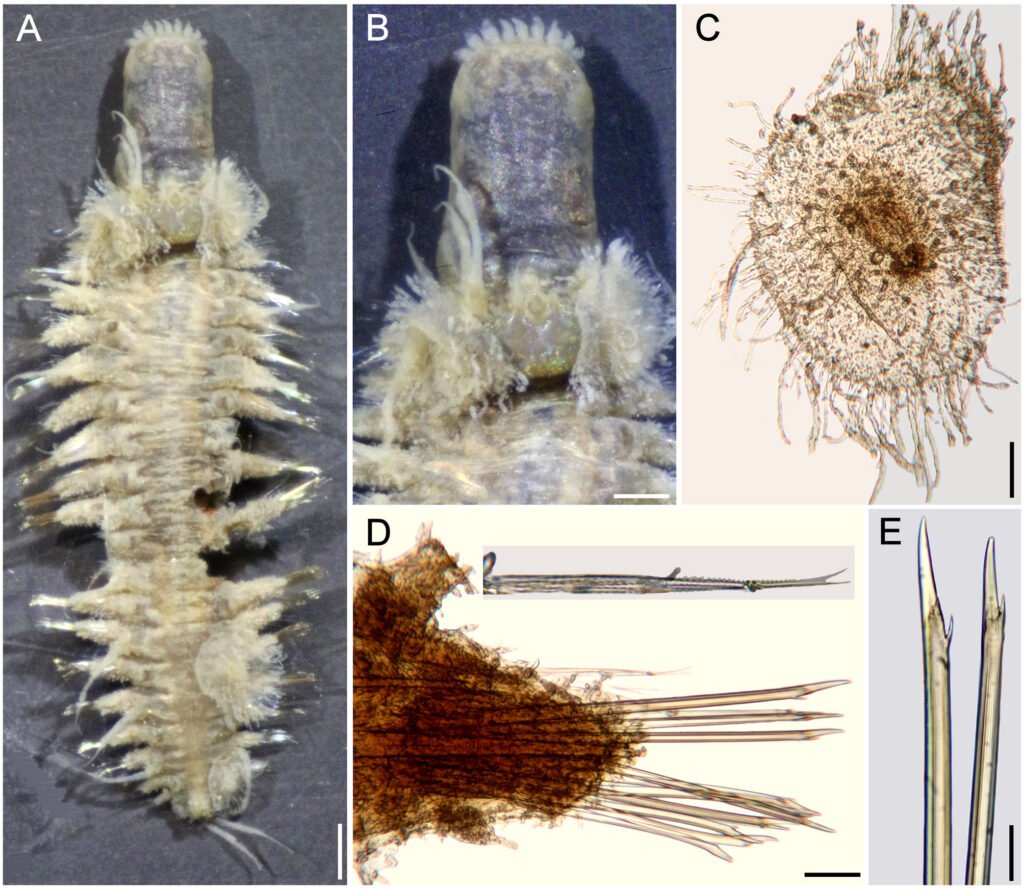

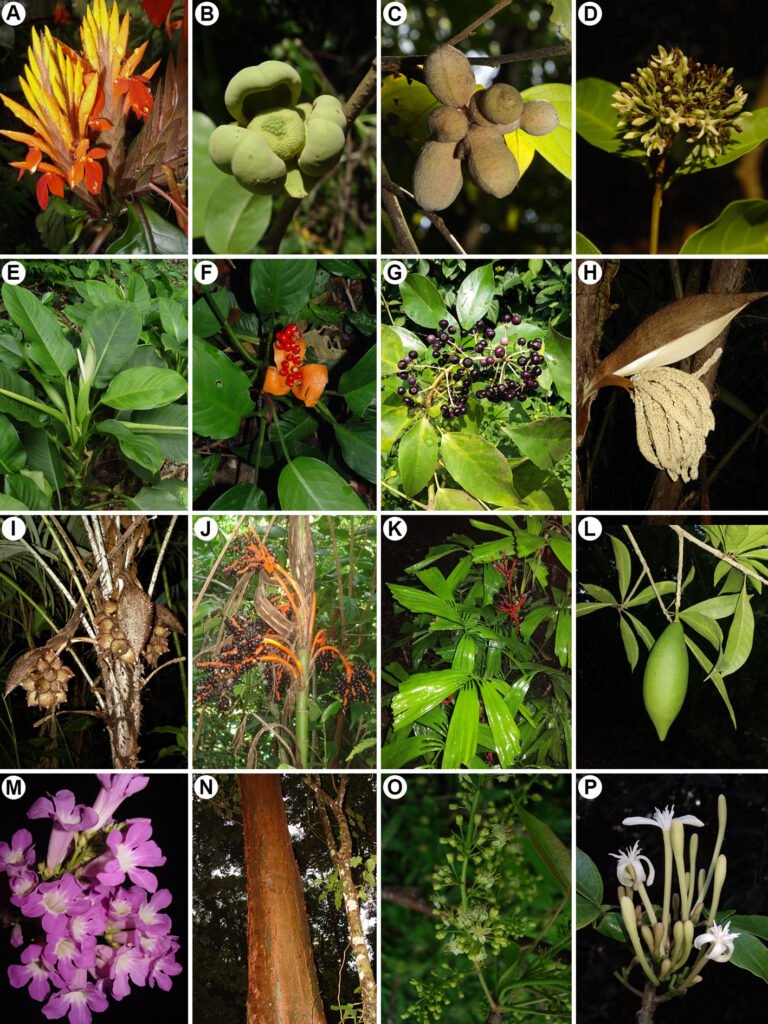

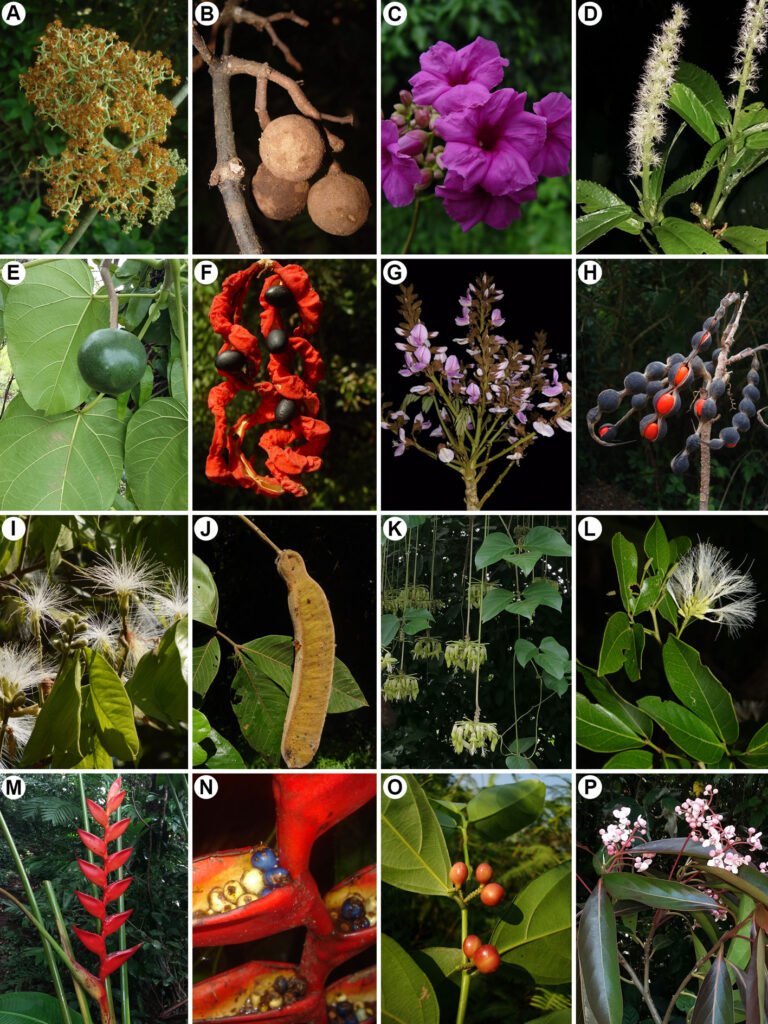

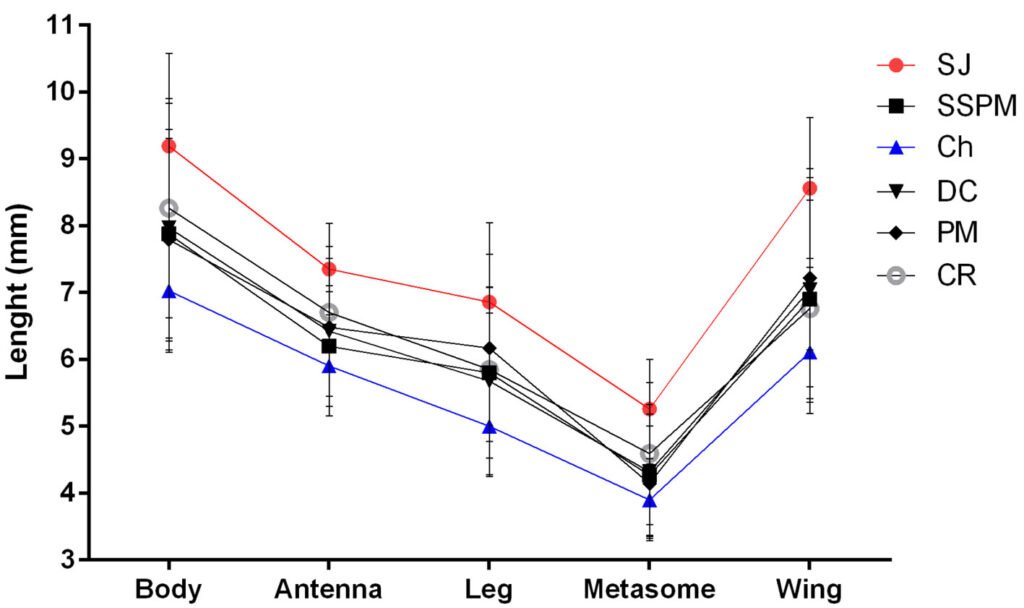

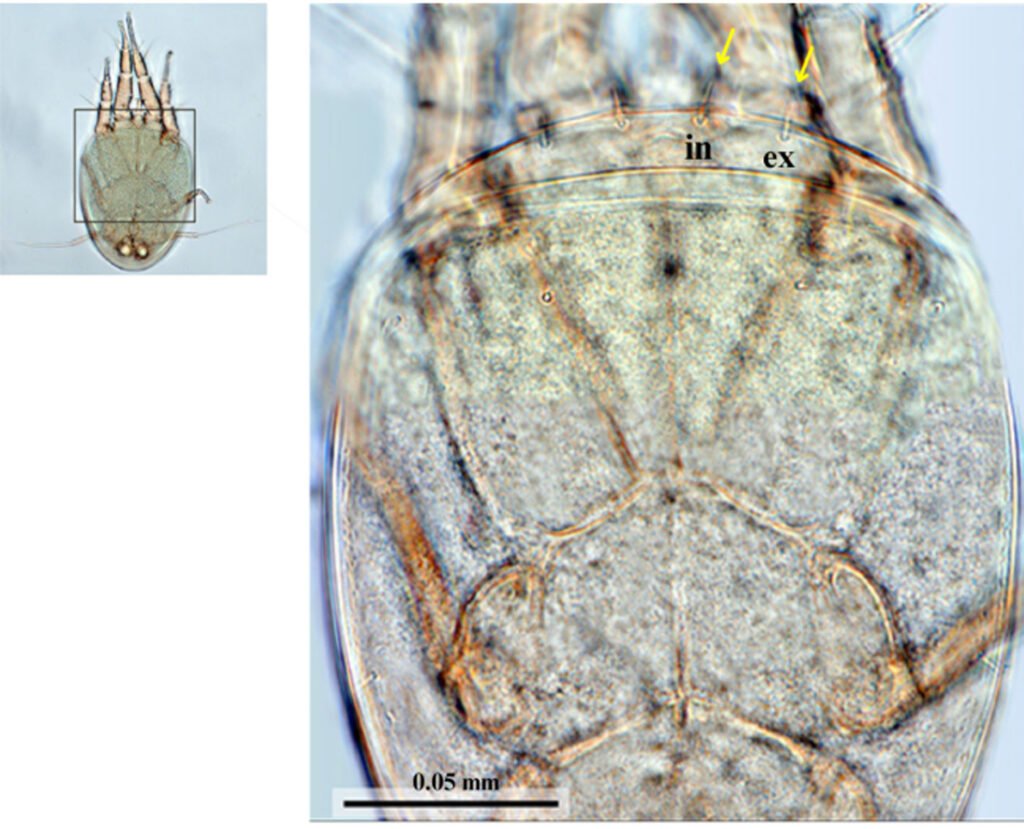

Description of holotype subadult female. Body robust; shape and tagmosis as usual in female Monstrilla (Suárez-Morales 1994a, 2019). Total body length 2.92 mm, measured from anterior end of cephalothorax to posterior margin of anal somite. Cephalothorax length 1.74 mm, representing about 60% of total body length, containing thick egg mass (Fig. 1A). Oral cone located 0.53 of way back along ventral surface of cephalothorax. Cephalic region with weakly produced forehead (Fig. 2A). All 3 cups of naupliar eye with pigment absent (Figs. 1A, B, 2A, 3D). Preoral area with ventral ornamentation of small, nipple-like cuticular processes (nlp) with adjacent fields of integumental wrinkles and anterior cluster of pores (apc) (Figs. 3D, 4B). Antennules slender, relatively short (588 µm) and thick, corresponding to 33% of cephalothorax length and almost 20 % of total body length (Fig. 1A). Antennules indistinctly 5-segmented (1-5 in Fig. 1B), segment 1 separate but segments 2-5 partly fused (Figs. 1B, 3A), with intersegmental division 2-3 marked by weak constriction. In terms of current nomenclature for antennular armature of female monstrilloid copepods (Grygier & Ohtsuka, 1995), element 1 present on first segment (Fig. 3A). Second segment armed as usual with elements 2v1-3, 2d1,2, and long element IId (Figs. 3A, B, 4C), but additionally with conical process on distal inner margin (arrowed in Fig. 3B). Putative third segment with setiform element 3, but pair of short, spiniform elements replacing usual long, setiform elements IIIv and IIId (Fig. 3A). Putative fourth segment armed with elements 4v1-3, long 4aes, and elements IVd and IVv (Fig. 3A), as well as conical spiniform process on inner proximal margin (arrowed in Fig. 3A). Fifth segment carrying setal elements Vv, Vd, Vm, 61, 2, aesthetasc 6aes, plus only 2 unbranched setae of “b” group (b6 and b3) on outer margin, as well as distal spiniform process at insertion of elements 61, 2, and 6aes (Figs. 2B, 3C). First pedigerous thoracic somite incorporated into cephalothorax, succeeding 3 free pedigerous somites each bearing pair of biramous swimming legs, all 3 together accounting for 31.3% of total body length (Fig. 1A). Endopodites and exopodites of swimming legs 1-4 unequal (exopods longer), triarticulate, and with same setal armature in each leg, except exopod of leg 1 with one fewer seta on the distal segment (Fig. 4D).

Armature formula of swimming legs: leg 1: basis 1-0, endopodite 0-1; 0-1; 1-2-2, exopodite I-1; 0-1; I-2-2; legs 2-4: basis 1-0, endopodite 0-1; 0-1; 1-2-2, exopodite I-1; 0-1; I-2-3. Coxae of legs 1-4 unarmed; each pair medially joined by subrectangular intercoxal sclerite about 1.3 times as long as broad with curved distal margin; anterior surface of sclerites 2-4 ornamented with rows of minute hyaline spinules. Basis separated from coxa posteriorly by diagonal articulation, lacking usual basipodal outer seta in legs 2-4. Outer distal corner of first and third exopodal segments of swimming legs 1-4 each with short, slender spiniform element about 1/3 as long as its segment. All natatory setae lightly and biserially plumose except for spiniform seta on outer distal corner of third exopodal segments, this being lightly setulate along inner side and bearing continuous row of small denticles along outer margin (Fig. 4D). Fifth legs medially conjoined, arising ventrally from posterior margin of fifth pedigerous somite (Fig. 4A), each being represented by elongate bilobed structure with its outer (exopodal) lobe armed with 2 subequally long apical setae. Unarmed and smooth inner (endopodal) lobe arising from proximal inner margin of outer lobe, almost reaching distal tip of latter. Urosome short (length = 389 µm long), accounting for 13.1% of total body length and consisting of fifth pedigerous somite, genital double-somite, 2 free abdominal somites, and caudal rami (Figs. 1C, 4A). Genital double somite representing 28.8% of length of urosome. Preanal somite about half as long as anal somite (Fig. 4A). Medial ventral surface of genital double-somite moderately swollen, bearing basally conjoined and posteriorly directed ovigerous spines (Fig. 4A). These spines (os in Figs. 1D, 4A) relatively short, corresponding to 21% of total body length and reaching to mid-length of caudal setae, each narrowing in its distal half to thin, seemingly socketed, seta-like section (Figs. 1D, 4A). Caudal rami subrectangular, 1.25 times as long as wide, moderately divergent, bearing 3 strong and subequally long terminal setae, as usual in genus (Figs. 1D, 4A), among 6 setal elements in all (I-VI), with innermost seta (VI) being shortest and proximal outer seta (I) being longest (Fig. 4A).

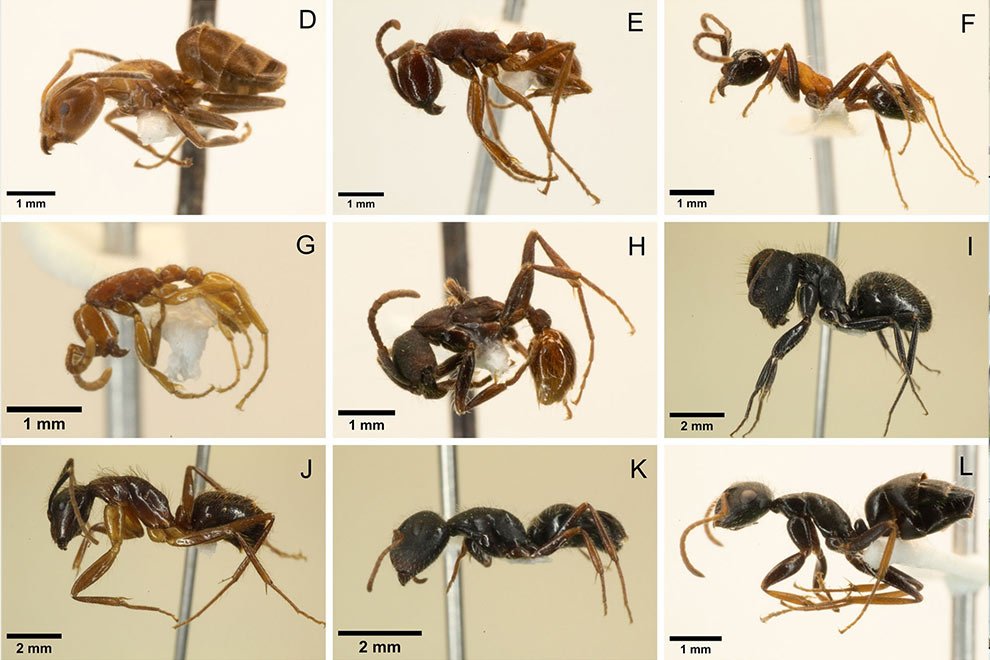

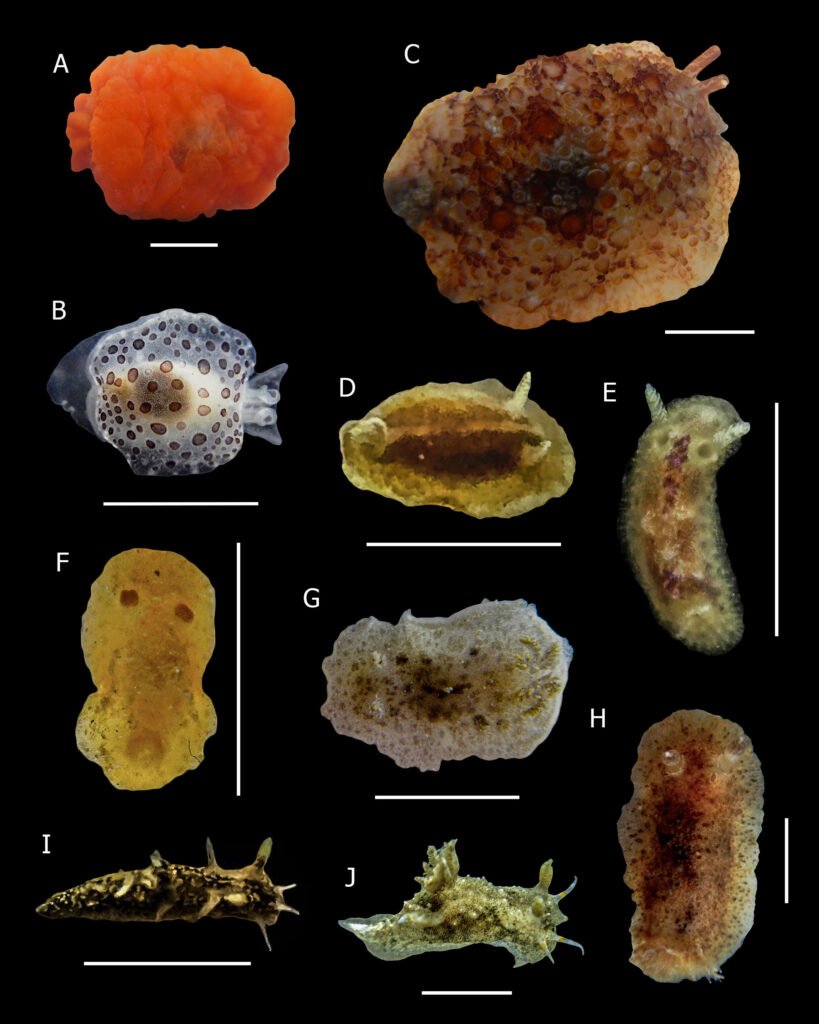

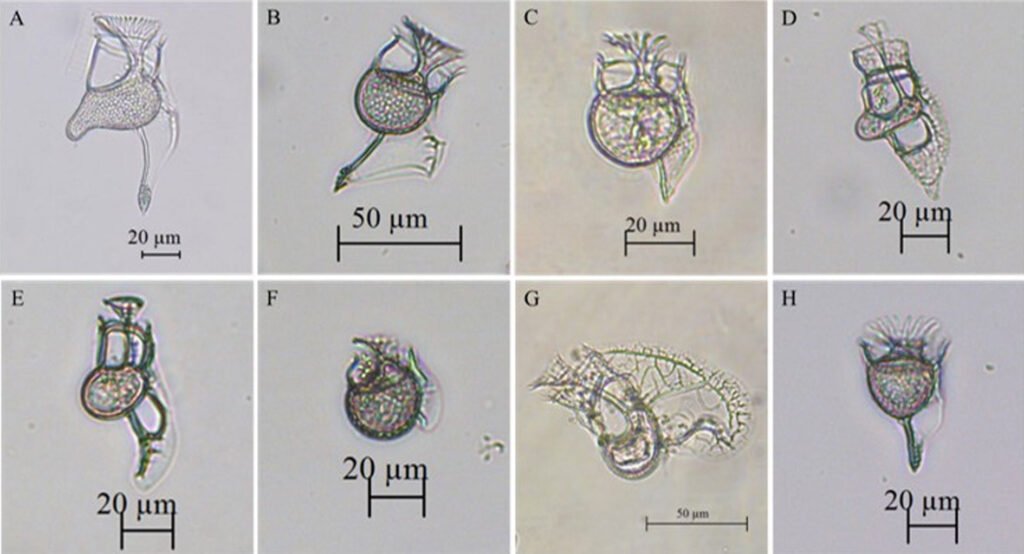

Figure 1. Monstrilla hendrickxi sp. n., from the Gulf of California, holotype female, digital photos. A, Habitus, dorsal view; B, anterior half of cephalothorax with 5- segmented antennules (1-5), ventral view; C, urosome, ventral view, showing ovigerous spines (os) arising from genital double-somite, fifth legs (P5) with 2 distal setae (1, 2), and caudal setae I-VI; D, distal part of ovigerous spines and caudal rami showing setae I-VI, ventral view.

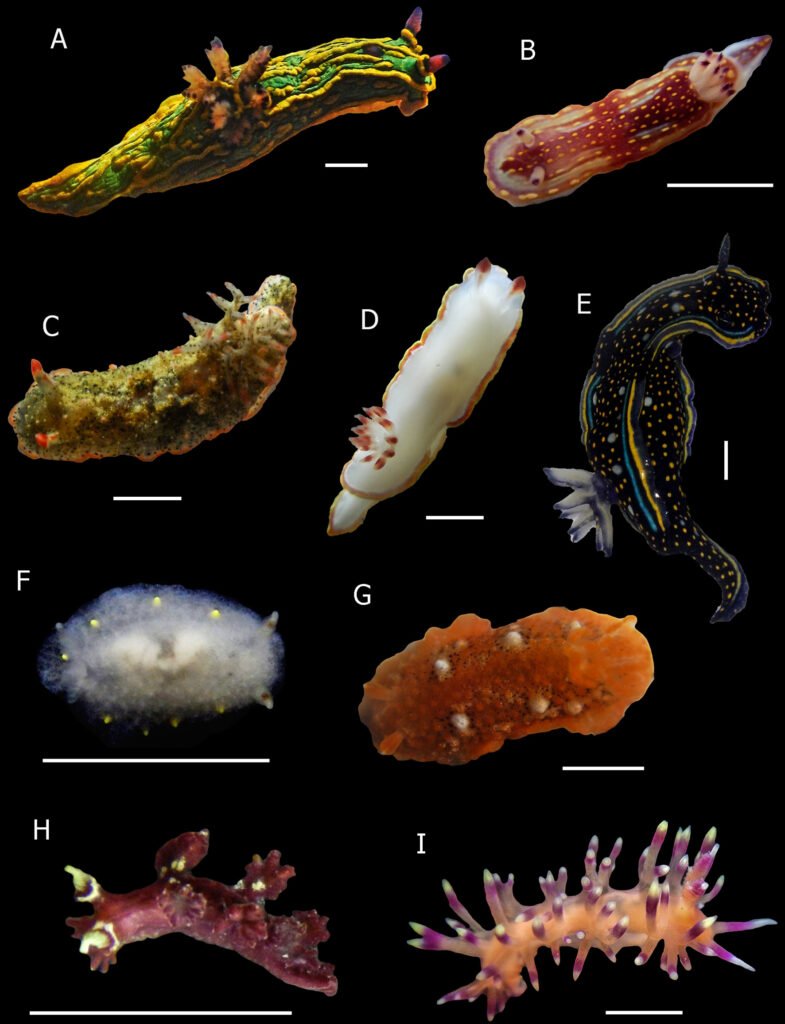

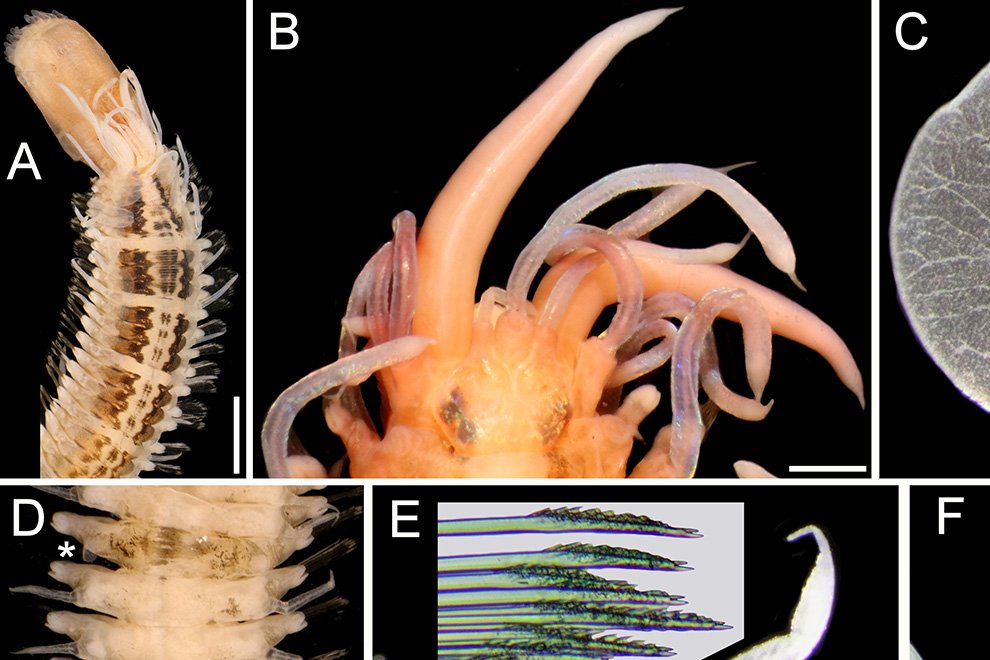

Figure 2. Monstrilla hendrickxi sp. n., from the Gulf of California, holotype female, digital photos. A, Anterior part of cephalothorax showing weakly produced forehead and lack of eyes; B, antennule showing dorsal segmentation; C, fifth leg (P5) showing exopodal (exp) and endopodal (enp) lobes, ventral view; D, apical elements (61, 62, and 6aes) of distal antennular segment.

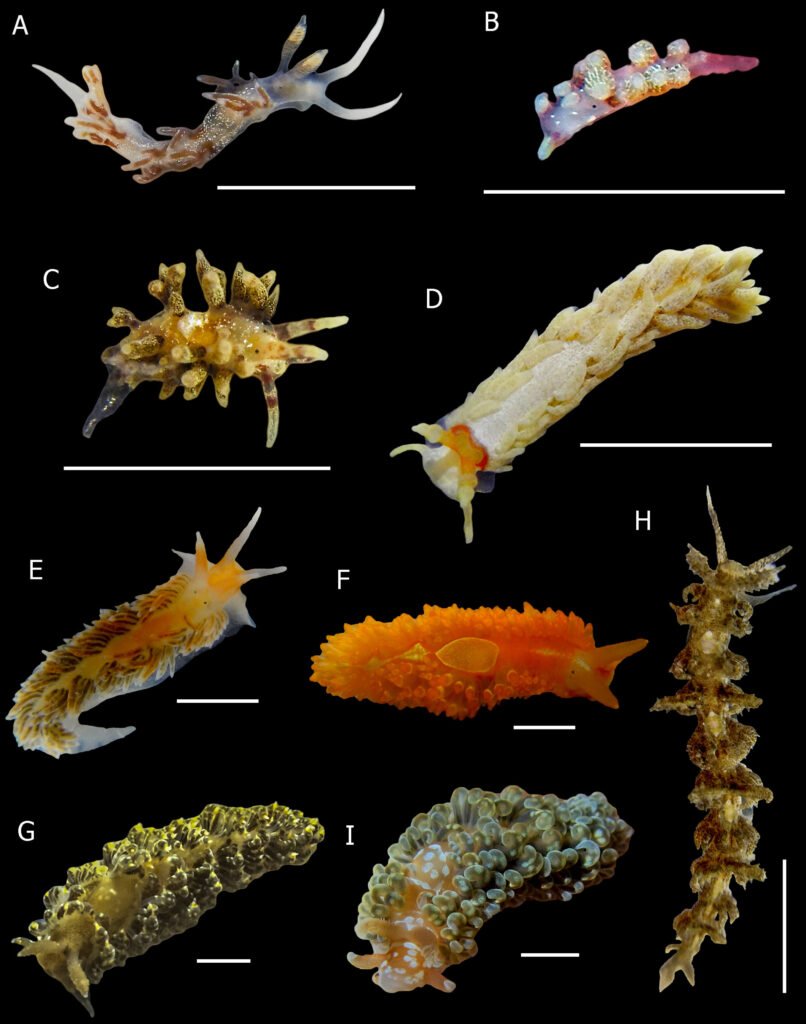

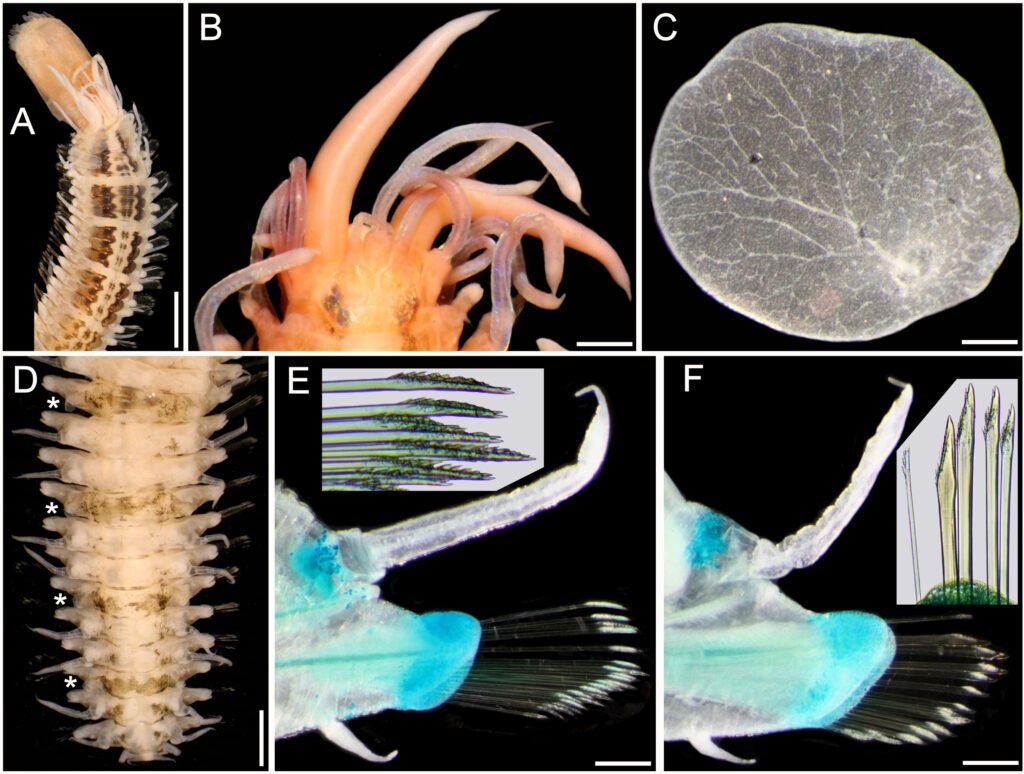

Figure 3. Monstrilla hendrickxi sp. n., from the Gulf of California, holotype female. A, Antennule showing setation labelled in accordance with Grygier and Ohtsuka’s (1995) nomenclature, ventral view; B, similarly labelled setation of second antennular segment, ventral view, also showing segment’s inner distal conical process (arrow); C, distal (fifth) segment of antennule, ventral view, showing similarly labelled setation and distal process (arrow); D, anterior third of cephalothorax, ventral view, showing integumental ornamentation, including nipple-like processes (nlp), anterior pore cluster (apc), and preoral pores (pp). Scales A-D = 100 µm.

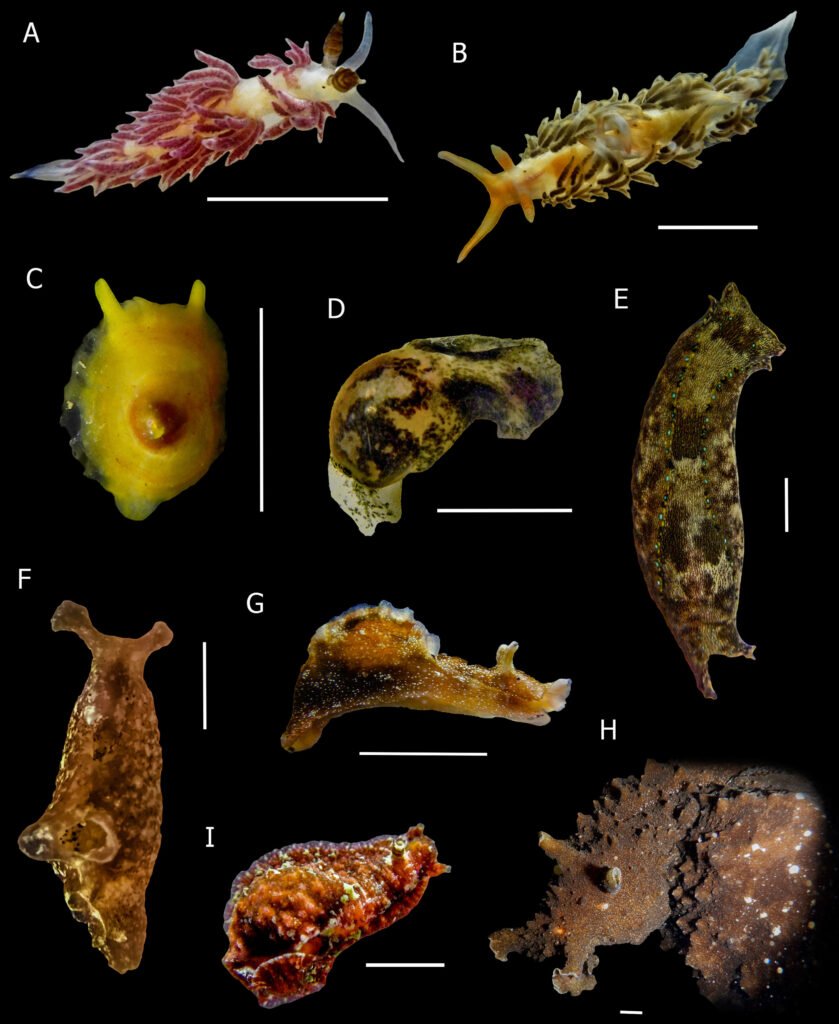

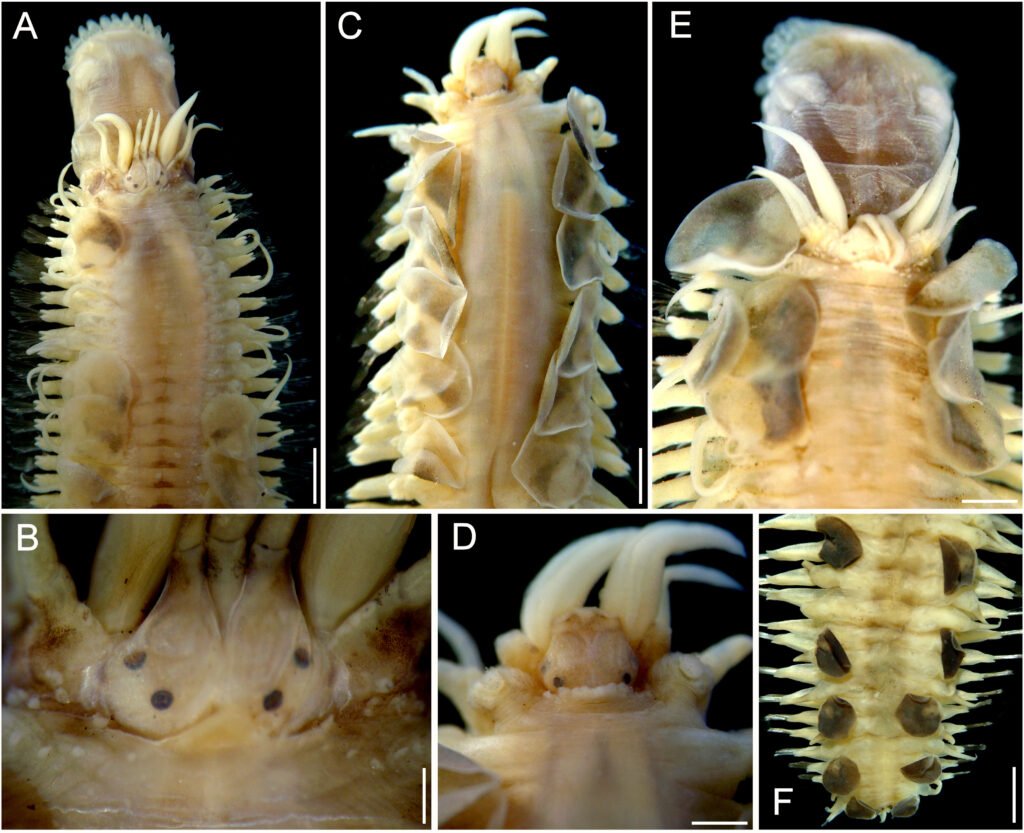

Figure 4. Monstrilla hendrickxi sp. n., from the Gulf of California, holotype female. A, Urosome, ventral view, showing bilobed fifth leg with exopodal (exp) and endopodal (enp) lobes, ovigerous spines (os), and caudal rami setation (I-VI); B, anterior half of cephalothorax, ventral view, showing unlayed internal egg mass (em), oral cone (oc), and nipple-like processes (nlp); C, antennule segments 1-3 (S1-S3), ventral view, showing setation labelled in accordance with Grygier and Ohtsuka’s (1995) nomenclature, including modified setae IIIv and IIId; D, right leg 1, semi-lateral view, showing setation including basipodal seta (bs) and exopodal (exp) and endopodal (enp) rami. Scales A-D = 100 µm.

Taxonomic summary

Type locality. Southern Gulf of California, Mexico (25°53’15” N, 110°10’08” W). Sampling depth between 710 and 750 m.

Material examined. One subadult female (holotype), partially dissected and mounted on 2 semi-permanent glycerin slides sealed with acrylic nail varnish (ECO-CH-Z 11860). Epibenthic sledge, TALUD XVI B cruise, southern Gulf of California, Mexico, 31 May 2014.

Etymology. The specific name, a masculine genitive eponym, honors Dr. Michel E. Hendrickx (ICMyL-UNAM) for his sustained efforts and achievements in exploring the crustacean fauna of the Gulf of California and the Mexican Pacific.

Male. Unknown.

Host. Unknown.

Remarks

The sampling gear used to collect this specimen was an epibenthic sledge, not a plankton net; the latter is more efficient for capturing planktonic adult monstrilloids in surface waters. Epi-mesopelagic monstrilloids collected by sledge type gears have been reported from depths of 118 and 302 m in the North Atlantic (Suárez-Morales & Mercado-Salas, 2023), but those individuals were badly damaged even though the sledge had an attached plankton collector (Brandt et al., 2014). The specimen recovered from the TALUD XVI-B sledge sample was in reasonably good condition for taxonomic study.

The present subadult female monstrilloid from the Gulf of California can be readily assigned to the genus Monstrilla by its possession of the diagnostic generic features for females, including the presence of 2 somites between the genital double-somite and the anal somite, 6 caudal setae, and the oral cone’s location ventrally at nearly mid-length of the cephalothorax (Isaac, 1975; Suárez-Morales, 1994a). Among the species-level diagnostic features of M. hendrickxi sp. n., the most useful for comparison among congeneric species are the antennular structure and armature, the shape of leg 5, and the absence of eyes. These will be considered in sequence below.

The specifically distinctive characters of M. hendrickxi sp. n. include: 1) eyes and eye-related structures absent; 2) antennules relatively short, robust, representing nearly 33% of cephalothorax length, with segments 2-5 partly fused; 3) segments 2-5 furnished with modified setae or strong spiniform processes, 4) fifth antennulary segment with remarkably long, thick apical elements; 5) fifth leg bilobed, with digitiform endopodal lobe unarmed, exopodal lobe with 2 terminal setae; 6) 6 caudal setae, innermost seta (VI) being shortest, proximal outer seta (I) longest. The finding of subadult monstrillids in the plankton is not unusual and some species have been described from these individuals, including the first described monstrilloid copepod, Thaumaleus typica (Krøyer, 1842) (Grygier, 1994), Monstrilla capitellicola Hartman (1961), M. elongata Suárez-Morales, 1994a, and Monstrilla sp. from Hawaii (Suárez-Morales et al., 2014).

Partial or complete fusion of antennular segments 2-5 is found in several other species of Monstrilla, including M. ilhoii Lee & Chang, 2016, M. mariaeugeniae Suárez-Morales & Islas-Landeros, 1993, M. satchmoi Suárez-Morales & Dias, 2001, M. grandis Giesbrecht, 1891, M. gracilicauda Giesbrecht, 1893, and M. elongata Suárez-Morales, 1994a. None of these species displays the remarkable development of apical elements 61, 62, and 6aes observed in M. hendrickxi sp. n. The only available illustration of an antennule of M. nichollsi Davis, 1949 (= C. helgolandica) (Suárez-Morales pers. obs.) (cf. Nicholls, 1944: fig. 26, as Monstrilla sp.) shows a very long apical element on its fifth segment, which is probably identifiable as the aesthetasc 6aes. Elsewhere on the antennule, no congeneric species has modified setal elements IIId and IIIv on segment 3 or large, spiniform or conical processes on segments 2, 4, and 5 like those described in the new species.

Only a few known species originally described as Monstrilla possess a bilobed fifth leg with 2 setae on the outer (exopodal) lobe, 2 of them have been transferred to the genus Caromiobenella: C. helgolandica (Claus, 1863) and C. hamatapex (Grygier & Ohtsuka, 1995); the other species of Monstrilla sharing this character are M. mariaeugeniae, M. capitellicola, and M. leucopis Sars, 1921. Also, both Monstrilla sp. from Hawaii and M. capitellicola from Southern California (Hartman, 1961), likely represented by subadult individuals, also show only 2 setae on the outer lobe, a character conserved through the copepodiid stages CIII-V (Suárez-Morales et al., 2014). The new species M. hendrickxi differs from C. helgolandica, C. hamatapex, M. capitellicola, and M. leucopis, by its possession of a long, digitiform endopodal lobe, which is absent in these 4 species (Chang, 2014; Grygier & Ohtsuka, 1995; Sars, 1921; Zavarzin & Suárez-Morales, 2024). The corresponding endopodal lobe is clearly shorter in M. capitellicola (Hartman, 1961) than in the new species. Monstrilla wandelii Stephensen, 1913, and M. mariaeugeniae both exhibit a small, unarmed subtriangular endopodal lobe (Nicholls, 1944, fig 26; Park, 1967; Suárez-Morales & Islas-Landeros, 1993), which clearly differs from the elongate, digitiform endopodal lobe observed in M. hendrickxi sp. n.. Monstrilla nichollsi, a synonym of C. helgolandica (Suárez-Morales pers. obs.), was named by Davis (1949) based solely on Nicholl’s (1944, fig. 26) illustration of the fifth leg, thus allowing us to add C. helgolandica to the group of monstrillid species with 2 exopodal setae on the fifth leg exopodal lobe. It should be noted that the armature of the fifth leg exopodal lobe is conservative during the immature stages including the preadult CV (Suárez-Morales et al., 2014); changes in this character at the final molt are unlikely.

Monstrilla hendrickxi sp. n. is the only monstrilloid copepod in which no trace of the naupliar eye is present, although weakly developed visual structures have been observed previously in deep-living species (Suárez-Morales & Mercado-Salas, 2023). This contrasts with the usually well-developed, highly pigmented, three-cup naupliar eyes of most known monstrilloids. Functional eyes are probably extremely important for planktonic adult monstrilloids, allowing them, for example, to migrate to different light conditions in the water column and favor their dispersal (Suárez-Morales, 2018; Suárez-Morales & Gasca, 1990). The weak eye development of deep-living monstrilloids is likely an adaptive consequence of their aphotic habitat.

Monstrilla hendrickxi sp. n. is the fifth species of the copepod order Monstrilloida recorded from the Gulf of California, after Monstrilla gibbosa Suárez-Morales & Palomares-García, 1995, Spinomonstrilla spinosa (Park, 1967) (originally reported as Monstrilla spinosa), Cymbasoma californiense Suárez-Morales & Palomares-García, 1999, and recently M. leucopis Sars, 1921 (Suárez-Morales, 2019; Suárez-Morales & Palomares-García, 1999; Suárez-Morales & Velázquez-Ornelas, 2023).

Acknowledgements

We thank Michel E. Hendrickx (ICMyL-UNAM) for kindly allowing us to examine this specimen. Ship time for the TALUD XVI-B cruise was provided by the Coordinación de la Investigación Científica, UNAM, and partly supported by Conacyt (project # 179467). We also thank to an anonymous reviewer for the corrections made to improve this article.

References

Brandt, A., Havermans, C., Janussen, D., Jörger, K. M., Meyer-Löbbecke, A., Schnurr, S. et al. (2014). Composition and abundance of epibenthic-sledge catches in the South Polar Front of the Atlantic. Deep-Sea Research II, 108, 69–75. Doi?

Claus, C.(1863). Die frei lebenden Copepoden mit besonderer Berücksichtigung der Fauna Deutschlands, der Nordsee und des Mittelmeeres. Leipzig: Verlag von Wilhelm Engelmann.

Chang, C. Y. (2014). Two new records of monstrilloid copepods (Crustacea) from Korea. Animal Systematics, Evolution and Diversity, 30, 206–214. https://doi.org/10.5635/ASED.

2014.30.3.206

Cruz-Lopes da Rosa, J., Dias, C. O., Suárez-Morales, E., Weber, L. I., & Gomes-Fischer, L. (2021). Record of Caromiobenella (Copepoda, Monstrilloida) in Brazil and discovery of the male of C. brasiliensis: morphological and molecular evidence. Diversity, 13, 241. https://doi.org/

10.3390/d13060241

Dana, J. D. (1849). Conspectus crustaceorum, quae in orbis terrarum circumnavigatione, Carolo Wilkes, e classe Reipublicae foederatae duce, lexit et descripsit Jacobus D. Dana. Pars II. Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 2, 9–61.

Davis, C. C. (1949). A preliminary revision of the Monstrilloida, with descriptions of two new species. Transactions of the American Microscopical Society, 68, 245–255. https://doi.org/10.2307/3223221

Giesbrecht, W. (1891). Elenco dei Copepodi pescati dalla R. Corvetta ‘Vettor Pisani’ secondo la loro distribuzione geografica. Atti della Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, Classe di Scienze Fisiche Matematiche e Naturali Rendiconti, 4, 276–282.

Giesbrecht, W. (1893). Systematik und Faunistik der pelagischen Copepoden des Golfes von Neapel und der angrenzenden Meeres-Abschnitte. Fauna und Flora des Golfes von Neapel und der angrenzenden Meeres-Abschnitte, 19, 1–831.

Grygier, M. J. (1994) [dated 1993]. Identity of Thaumatoessa (= Thaumaleus) typica Krøyer, the first described monstrilloid copepod. Sarsia, 78, 235–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/00364827.1993.10413537

Grygier, M. J., & Ohtsuka, S. (1995). SEM observation of the nauplius of Monstrilla hamatapex, new species, from Japan and an example of upgraded descriptive standards for monstrilloid copepods. Journal of Crustacean Biology, 15, 703–719. https://doi.org/10.1163/193724095X00118

Grygier, M. J., & Ohtsuka, S. (2008). A new genus of monstrilloid copepods (Crustacea) with anteriorly pointing ovigerous spines and related adaptations for subthoracic brooding. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 152, 459–506. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.2007.00381.x

Hartman, O. (1961). A new monstrillid copepod parasitic in capitellid polychaetes in southern California. Zoologischer Anzeiger, 167, 325–334.

Huys, R., & Boxshall, G. A. (1991). Copepod evolution. London: Ray Society.

Huys, R., Llewellyn-Hughes, J., Conroy-Dalton, S., Olson, P. D., Spinks, J. N., & Johnston, D. A. (2007). Extraordinary host switching in siphonostomatoid copepods and the demise of the Monstrilloida: Integrating molecular data, ontogeny and antennulary morphology. Molecular Phylogenetics

and Evolution, 43, 368–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.

2007.02.004

Isaac, M. J. (1975). Copepoda, sub-order: Monstrilloida. Fiches d’Identification du Zooplancton, 144/145, 1–10.

Jeon, D., Lee, W., & Soh, H. Y. (2018). New genus and two new species of monstrilloid copepods (Copepoda: Monstrillidae): integrating morphological, molecular phylogenetic, and ecological evidence. Journal of Crustacean Biology, 38, 45–65. https://doi.org/10.1093 /jcbiol/rux095

Jeon, D., Lim, D., Lee, W., & Soh, H. Y. (2016). First use of molecular evidence to match sexes in the Monstrilloida (Crustacea: Copepoda), and taxonomic implications of the newly recognized and described partly Maemonstrilla-like females of Monstrillopsis longilobata Lee, Kim & Chang, 2016. Peer J, 13,e4938. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.4938

Krøyer, H. (1842). Crustacés. In P. E. Gaimard (Ed.), Atlas de Zoologie. Voyages de la Commission Scientifique du Nord en Scandinavie, en Laponie au Spitzberg et aux Feröe pendant les Anneés 1838, 1839 et 1840 sur la Corvette La Recherche, Commandée par M. Fabvre (pl. 41–43). Arthus Bertrand, Paris.

Lee, J., & Chang, C. Y. (2016). A new species of Monstrilla Dana, 1849 (Copepoda: Monstrilloida: Monstrillidae) from Korea, including a key to species from the North-west Pacific. Zootaxa, 4174, 396–409. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4174.1.24

Nicholls, A. G. (1944). Littoral Copepoda from South Australia (II) Calanoida, Cyclopoida, Notodelphyoida, Monstrilloida, and Caligoida. Records of the South Australian Museum, 8, 1–62.

Park, T. S. (1967). Two unreported species and one new species of Monstrilla (Copepoda: Monstrilloida) from the Strait of Georgia. Transactions of the American Microscopical Society, 86, 144–152.

Razouls, C., Desreumaux, N., Kouwenberg, J., & de Bovée, F. (2023). Biodiversity of marine planktonic copepods (morphology, geographic distribution, and biological data [2005-2023]). Sorbonne University, CNRS. http://copepodes.obs-banyuls.fr/en [Accessed April 28, 2022]

Sale, P. F, McWilliams, P. S., & Anderson, D. T. (1996). Composition of the near-reef zooplankton at Heron Reef, Great Barrier Reef. Marine Biology, 34, 59–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00390788

Sars, G. O. (1901). An account of the Crustacea of Norway with short descriptions and figures of all the species Vol. IV. Copepoda Calanoida. Bergen: The Bergen Museum.

Sars, G. O. (1921). An account of the Crustacea of Norway with short descriptions and figures of all the species, Vol. VIII. Copepoda Monstrilloida & Notodelphyoida. Bergen: The Bergen Museum.

Stephensen, K. (1913) Account of the Crustacea and the Pycnogonida collected by Dr. V. Nordmann in the summer of 1911 from northern Stromfjord and Giesecke Lake in West Greenland. Meddeleser om Groenland, 51, 55–77.

Suárez-Morales, E. (1994a). Monstrilla elongata, a new monstrilloid copepod (Crustacea: Copepoda: Monstrilloida) from a reef lagoon of the Caribbean coast of Mexico. Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington, 107, 262–267.

Suárez-Morales, E. (1994b). Thaumaleus quintanarooensis, a new monstrilloid copepod from the Mexican coasts of the Caribbean Sea. Bulletin of Marine Science, 54, 381–384.

Suárez-Morales, E. (2001). An aggregation of monstrilloid copepods in a western Caribbean reef area: ecological and conceptual implications. Crustaceana, 74, 689–696. https://doi.org/10.1163/156854001750377966

Suárez-Morales, E. (2011). Diversity of the Monstrilloida (Crustacea: Copepoda). Plos One, 6, e22915. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0022915

Suárez-Morales, E. (2018). Monstrilloid copepods: the best of three worlds. Bulletin of the Southern California Academy of Sciences, 107, 92–103. https://doi.org/10.22201/ib.20078706e.2020.91.3176

Suárez-Morales, E. (2019). A new genus of the Monstrilloida (Copepoda) with large rostral process and metasomal spines, and redescription of Monstrilla spinosa Park, 1967. Crustaceana, 92, 1099–1112. https://doi.org/10.1163/

15685403-00003925

Suárez-Morales, E., & Dias, C. O. (2001). Taxonomic report of some monstrilloids (Copepoda: Monstrilloida) from Brazil with description of four new species. Bulletin de l’Institut Royal des Sciences Naturelles de Belgique Biologie, 71, 65–81.

Suárez-Morales, E., & Gasca, R. (1990). Variación dial del zooplancton asociado a las praderas de Thalassia testudinum en una laguna arrecifal del Caribe Mexicano. Universidad y Ciencia, 7, 57–64.

Suárez-Morales, E., Harris, L. H., Ferrari, F. D., & Gasca, R. (2014). Late postnaupliar development of Monstrilla sp. (Copepoda: Monstrilloida), a protelean endoparasite of benthic polychaetes. Invertebrate Reproduction & Development, 58, 60–73.

Suárez-Morales, E., & Islas-Landeros, M. E. (1993). A new species of Monstrilla (Copepoda: Monstrilloida) from a reef lagoon off the Mexican coast of the Caribbean Sea. Hydrobiologia, 271, 45–48.

Suárez-Morales, E., & McKinnon, A. D. (2014). The Australian Monstrilloida (Crustacea: Copepoda) I. Monstrillopsis Sars, Maemonstrilla Grygier & Ohtsuka, and Australomonstrillopsis gen. nov. Zootaxa, 3779, 301–340. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3779.3.1

Suárez-Morales, E., & McKinnon, A. D., (2016). The Australian Monstrilloida (Crustacea: Copepoda) II. Cymbasoma Thompson, 1888. Zootaxa Monographs, 4102, 1–129. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4102.1.1

Suárez-Morales, E., & Mercado-Salas, N. F. (2023). Two new species of Cymbasoma (Copepoda: Monstrilloida: Monstrillidae) from the North Atlantic. Journal of Natural History, 57, 1312–1330. https://doi.org/10.5852/ejt.

2024.917.2395

Suárez-Morales, E., Paiva Scardua, M., & Da Silva, P. M. (2010). Occurrence and histopathological effects of Monstrilla sp. (Copepoda: Monstrilloida) and other parasites in the brown mussel Perna perna from Brazil. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 90, 953–958. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025315409991391

Suárez-Morales, E., & Palomares-García, R. (1995). A new species of Monstrilla (Copepoda: Monstrilloida) from a coastal system of the Baja California Peninsula, Mexico. Journal of Plankton Research, 17, 745–752. https://doi.org/

10.1093/plankt/17.4.745

Suárez-Morales, E., & Palomares-García, R. (1999). Cymbasoma californiense, a new monstrilloid (Crustacea: Copepoda: Monstrilloida) from Baja California, Mexico. Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington, 112, 189–198.

Suárez-Morales, E., Vásquez-Yeomans, L., & Santoya, L. (2020). A new species of the Cymbasoma longispinosum species-group(Copepoda, Monstrilloida, Monstrillidae) from Belize, western Caribbean Sea. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 91, e913176. https://doi.org/10.22201/ib.

20078706e.2020.91.3176

Suárez-Morales, E., & Velázquez-Ornelas, K. E. (2023). First record of Monstrilla leucopis G.O. Sars, 1921 (Copepoda: Monstrilloida: Monstrillidae) from the Eastern Pacific. Crustaceana, 96, 1183–1190. https://doi.org/10.1163/156854

03-bja10334

Thompson, I. C. (1888). Copepoda of Madeira and the Canary Islands, with descriptions of new genera and species. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 20, 145–156. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.1888.tb01443.x

Walter, T. C., & Boxshall, G. A. (2022). World of copepods database Cymbasoma Thompson I.C., 1888. Accessed through: World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS)at: https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=119778 on 2022-04-23

Zavarzin, D., & Suárez-Morales, E. (2024). First record of Caromiobenella helgolandica (Claus, 1863) (Copepoda: Monstrilloida: Monstrillidae) from the Okhotsk Sea. Crustaceana, 97, 151–157. https://doi.org/10.1163/15685403-

bja10345

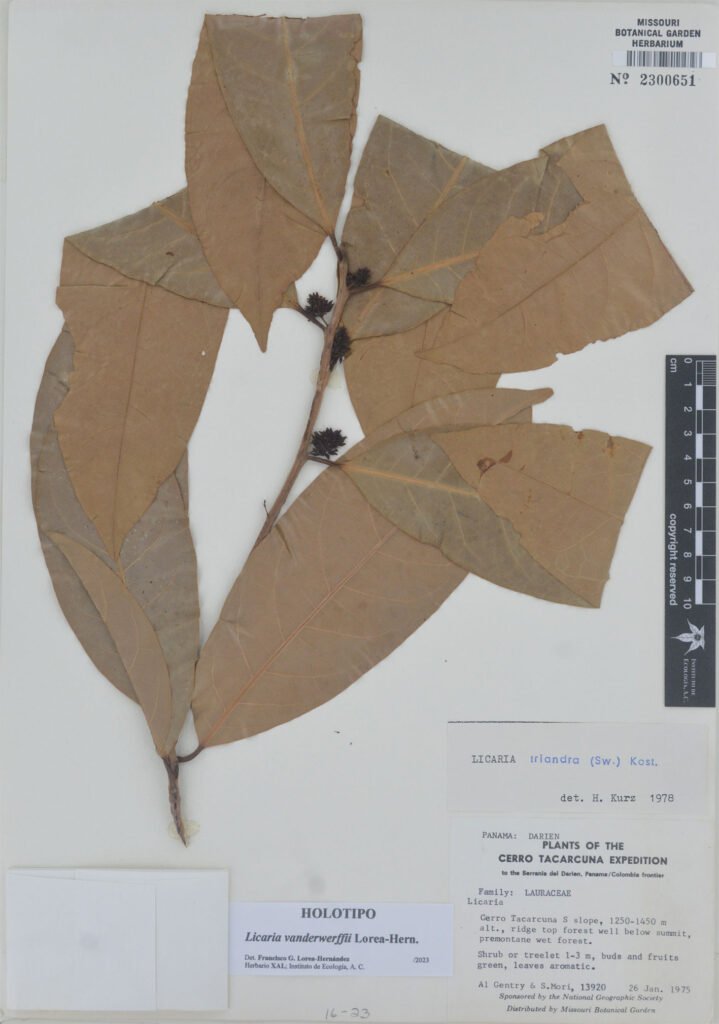

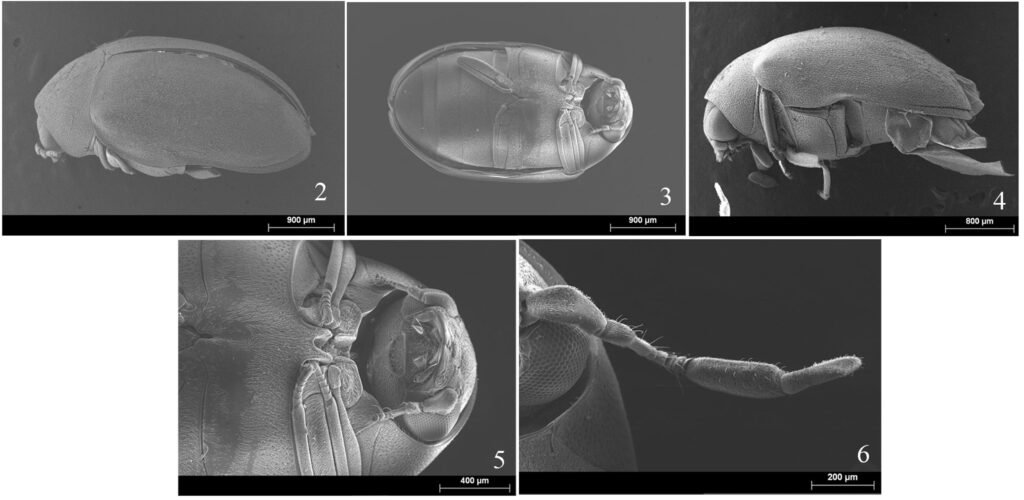

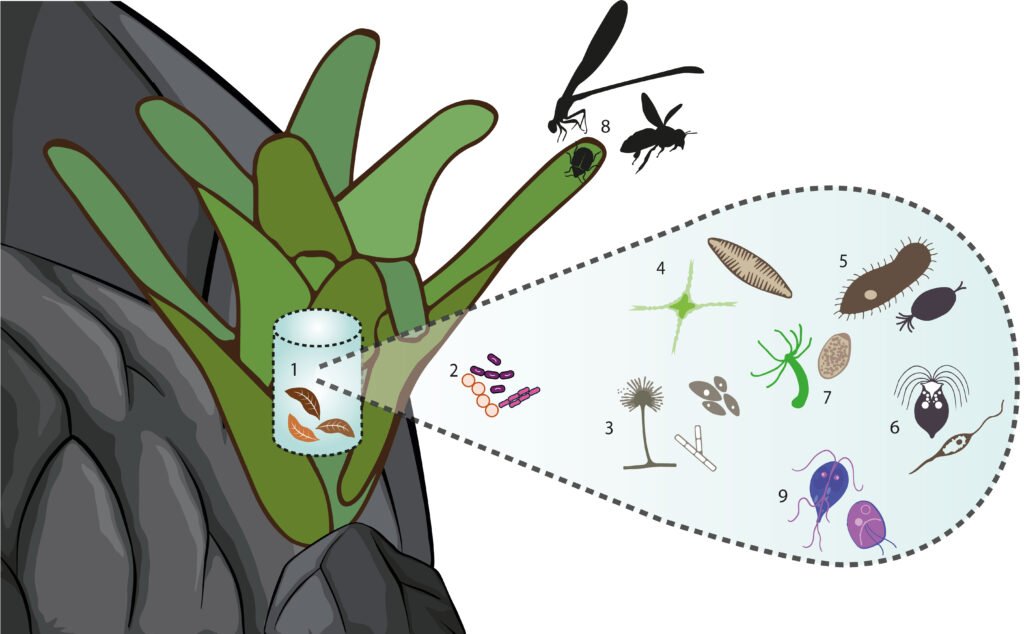

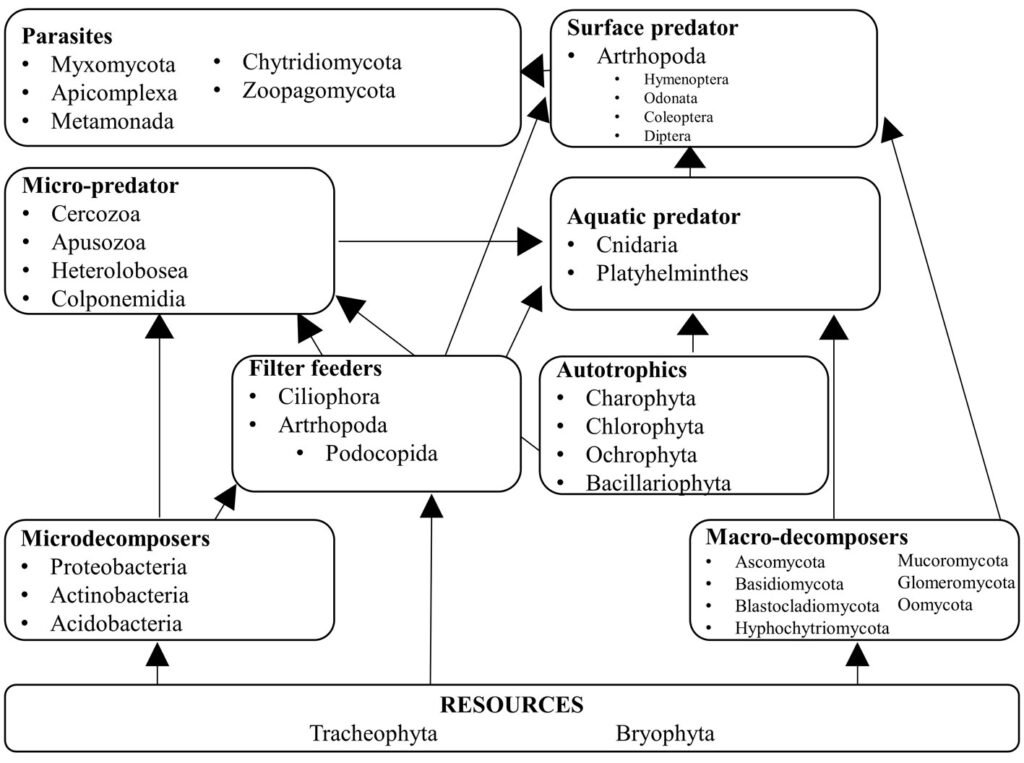

A new species of Aleuropleurocelus (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) and key to the ceanothi group from Mexico

Vicente Emilio Carapia-Ruiz*

Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos, Escuela de Estudios Superiores de Xalostoc, Av. Nicolas Bravo s/n, 62740 Xalostoc, Morelos, Mexico

*Corresponding author: vicente.carapia@uaem.mx (V.E. Carapia-Ruiz)

Received: 25 February 2024; accepted: 24 June 2024

http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:4751138D-9FD4-4095-A858-3A6A4F6B8A47

Abstract

A new species of whitefly, Aleuropleurocelus tecomastans, is described. The studied specimens were found in the municipality of Acapulco, State of Guerrero, Mexico on Tecoma stans (L.) (Bignoniaceae) leaves. A dichotomous key to identify members of Aleuropleurocelus group ceanothi, defined by a transverse suture of the molt which reaches the submarginal line, is provided. Photographs of morphological pupal structures are given and diagnostic separation to other related species is discussed.

Keywords: Aleyrodinae; Aleuropleurocelus ceanothi; Whitefly

© 2024 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Biología. Este es un artículo Open Access bajo la licencia CC BY-NC-ND

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Una especie nueva de Aleuropleurocelus (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) y clave para el grupo ceanothi de Mexico

Resumen

Una especie nueva de mosca blanca, Aleuropleurocelus tecomastans, es descrita. Los especímenes estudiados fueron encontradosen el municipio de Acapulco, Estado de Guerrero, México sobre Tecoma stans (L.) (Bignoniaceae). Se provee una clave dicotómica para identificación de especies de Aleuropleurocelus grupo ceanothi, definido por una sutura transversa de la muda que termina en la línea submarginal. Se proporcionan fotografías de las estructuras morfológicas del pupario y se analiza la separación diagnóstica en otras especies relacionadas.

Palabras clave: Aleyrodinae; Aleuropleurocelusceanothi; Mosca blanca

Introduction

The genus Aleuropleurocelus was described by Drews and Sampson (1956), comprising 8 species and an identification key to all Californian species was included (Drews & Sampson, 1958). Later Dooley et al. (2010) described A. nevadensis Dooley, while Polaszek and Gill (2011) added A. hyptisemoryi Gill to the genus. Nowadays, 19 species of Mexican species of Aleuropleurocelus are known and have been largely studied by Carapia-Ruiz (2023), Carapia-Ruiz (2020a, b), Carapia-Ruiz and Sánchez-Flores (2019a, b), Carapia-Ruiz et al. (2018a, b, 2020, 2023), Sánchez-Flores and Carapia-Ruiz (2018a, b), Sánchez-Flores et al. (2018a, b, 2020, 2021). The genus is segregated into 3 major groups: abnormis (semioval), nigrans, and ceanothi according to Dooley et al. (2010) and Sánchez-Flores et al. (2021).

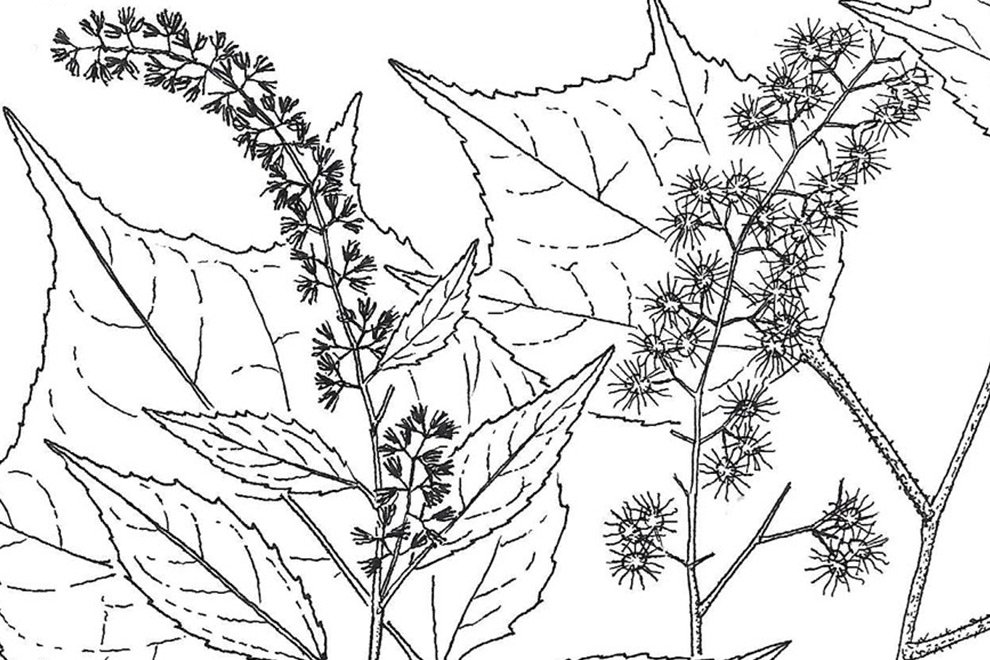

The ceanothi group, in which the transverse suture of molt ends at the submarginal line is included, A. granulata (Sampson & Drews), and the morphologically related species A. sampsoni Sánchez-Flores & Carapia-Ruiz and A. pseudogranulata Carapia-Ruiz & Sánchez-Flores. While collecting puparia of Aleyrodidae in Acapulco Guerrero, an unknown species of this group with distinctive characters was found. The objective of this contribution is to describe a new species and provide a key to all species of Aleuropleurocelus group ceanothi.

Materials and methods

The specimens were collected on the underside of the leaves of Tecoma stans (L.). in Acapulco, Guerrero. The specimens once taken were retained ethanol and thus transferred to the Laboratorio de Entomología, Escuela de Estudios Superiores de Xalostoc of the Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos, to be fully processed and mounted in permanent preparation with Canada balsam on slides for further study under stereomicroscope and facilitating identification following specialized literature such as Drews and Sampson (1958), Martin (2004, 2005), and Sanchez-Flores et al. (2021). After preparations, specimens were observed under a Motic BA 320 phase contrast optical microscope considering several magnifications: 4X 100X, 400X and 1,000X. The terminology used follows Drews and Sampson (1956) and Martin (2005). The studied specimens are deposited at Colección Nacional de Insectos (CNIN), Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. México City, Mexico.

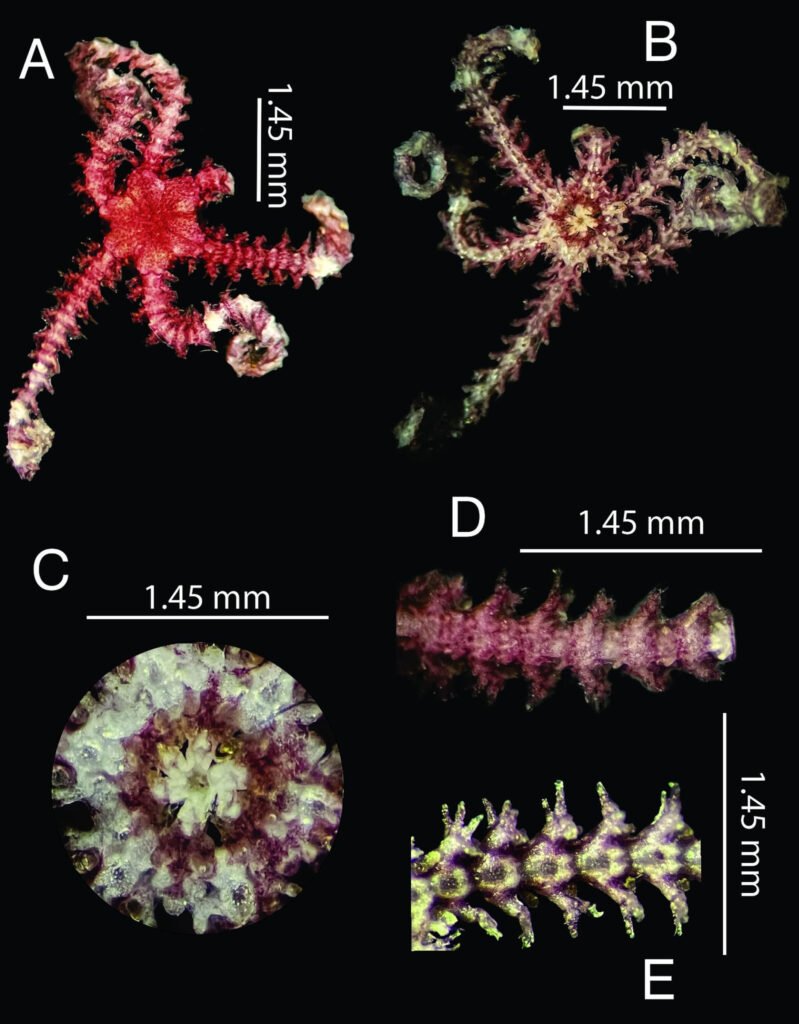

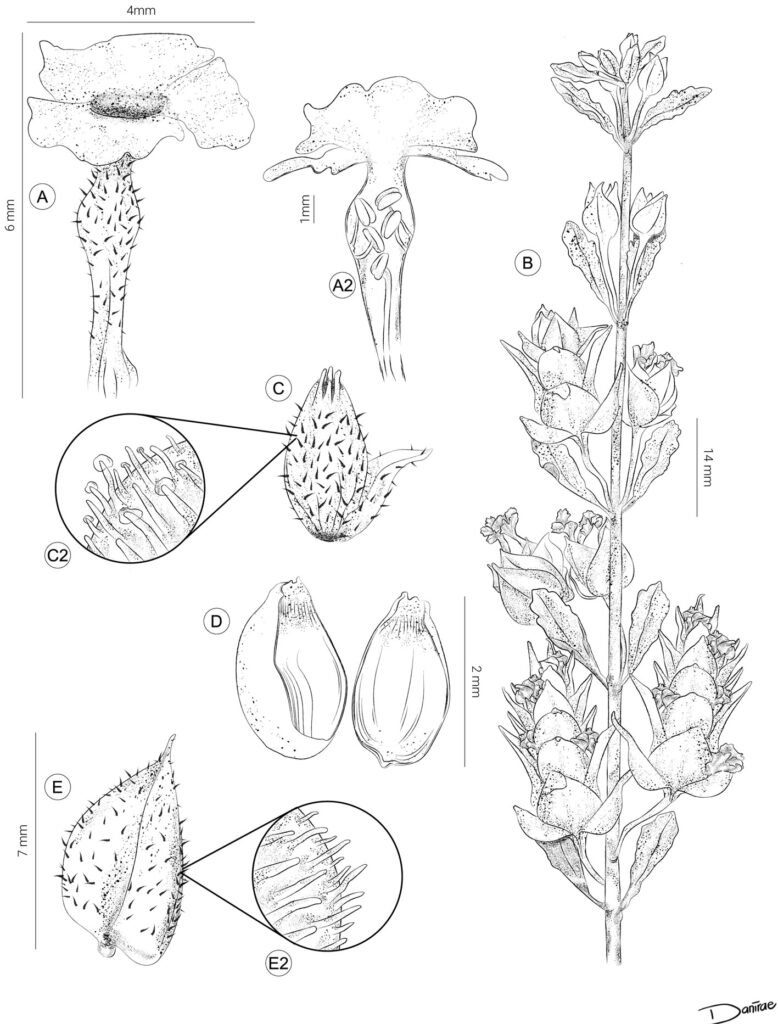

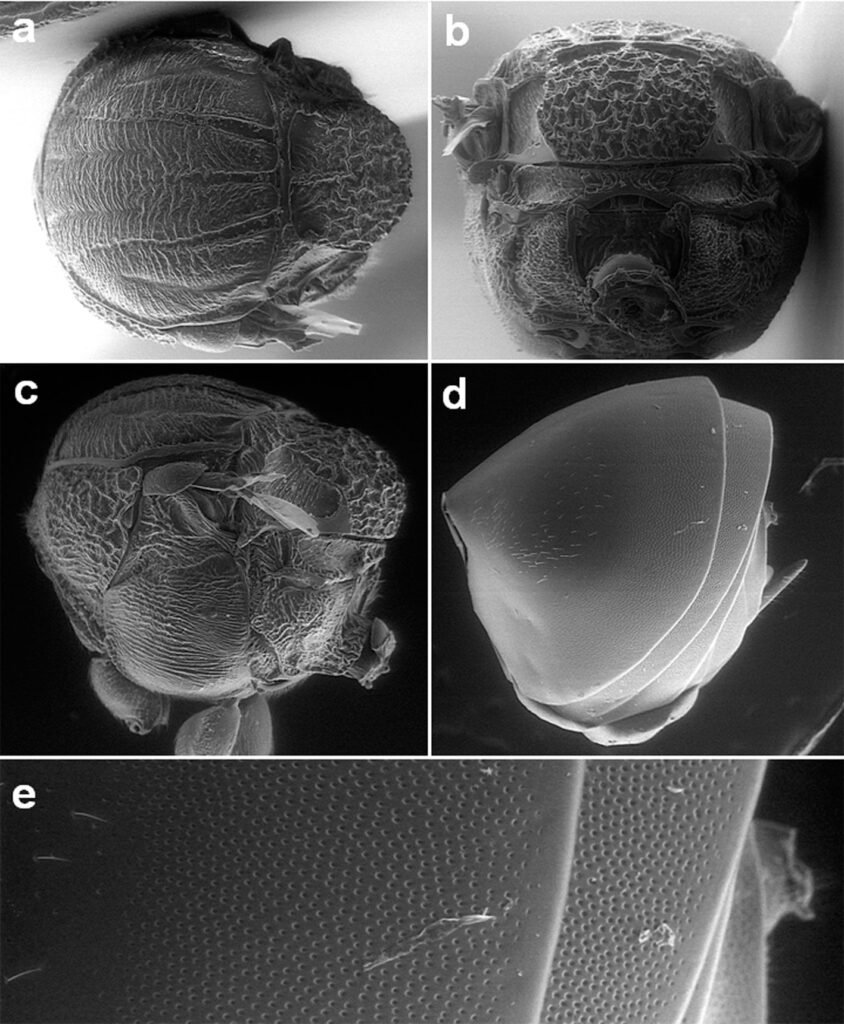

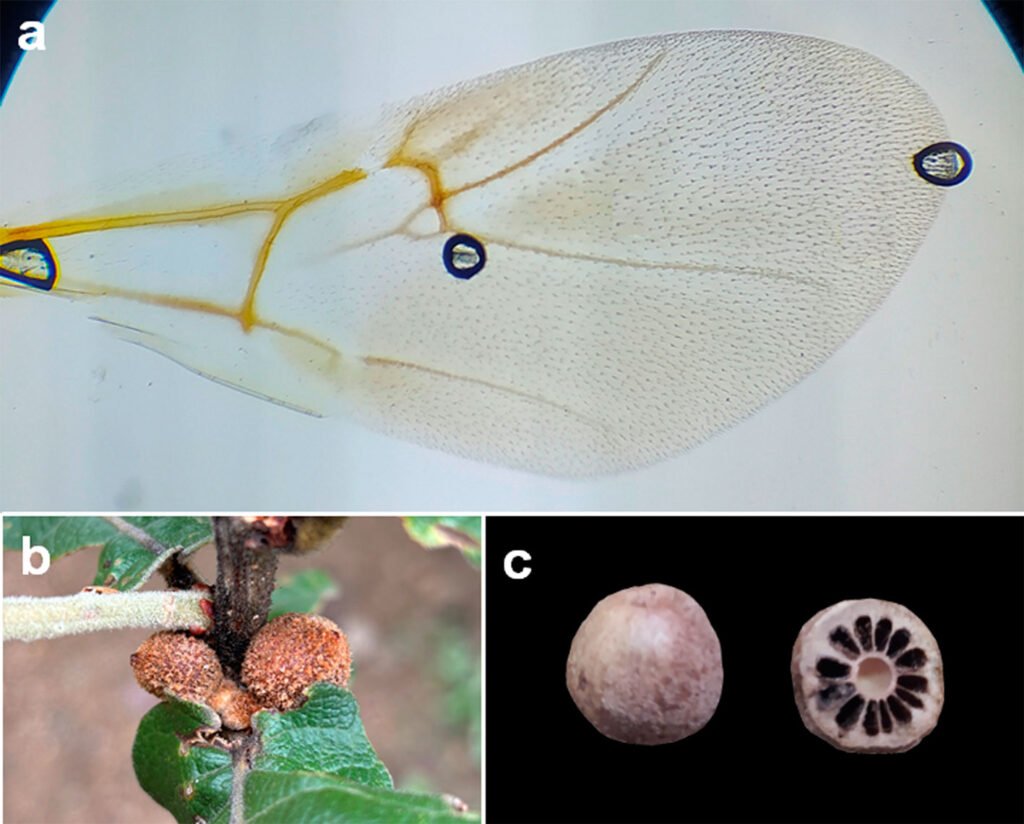

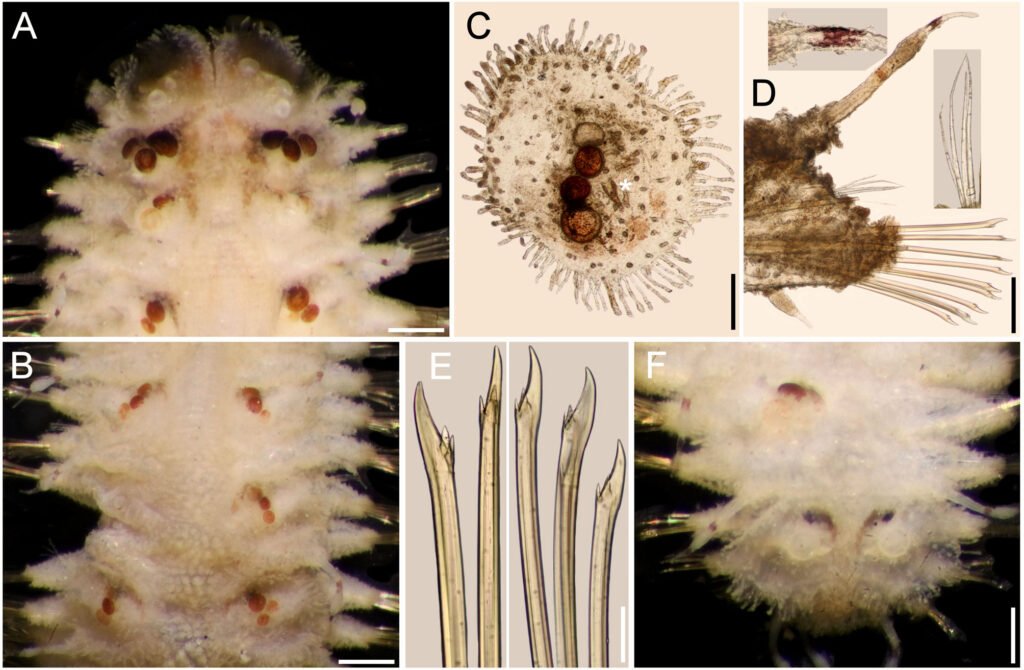

Description

Aleuropleurocelus tecomastans n. sp. Carapia-Ruiz

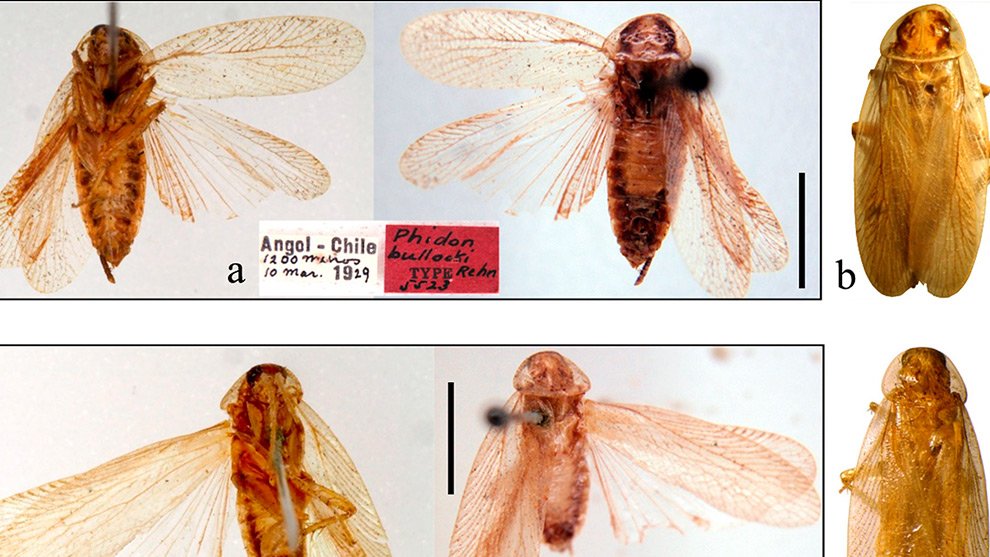

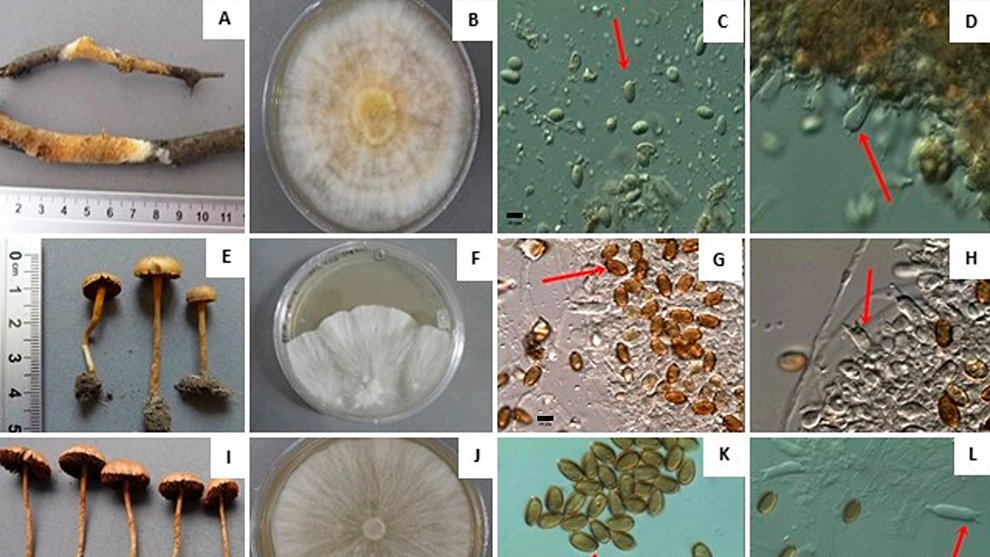

(Figs. 1-9)

http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:113654EB-09

53-4C95-9CFB-3FFFF8B3F8BE

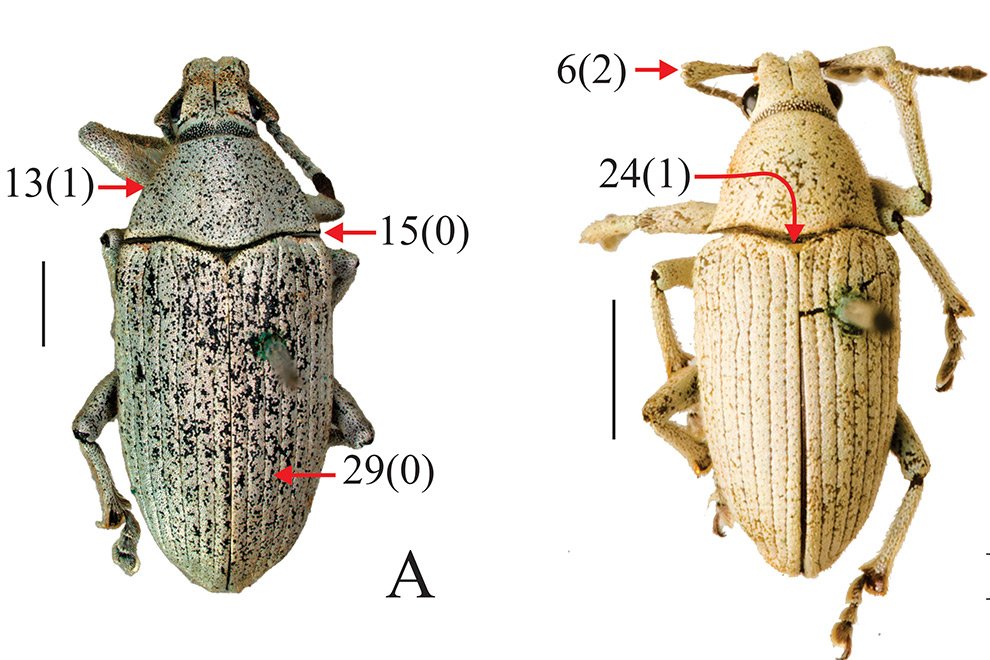

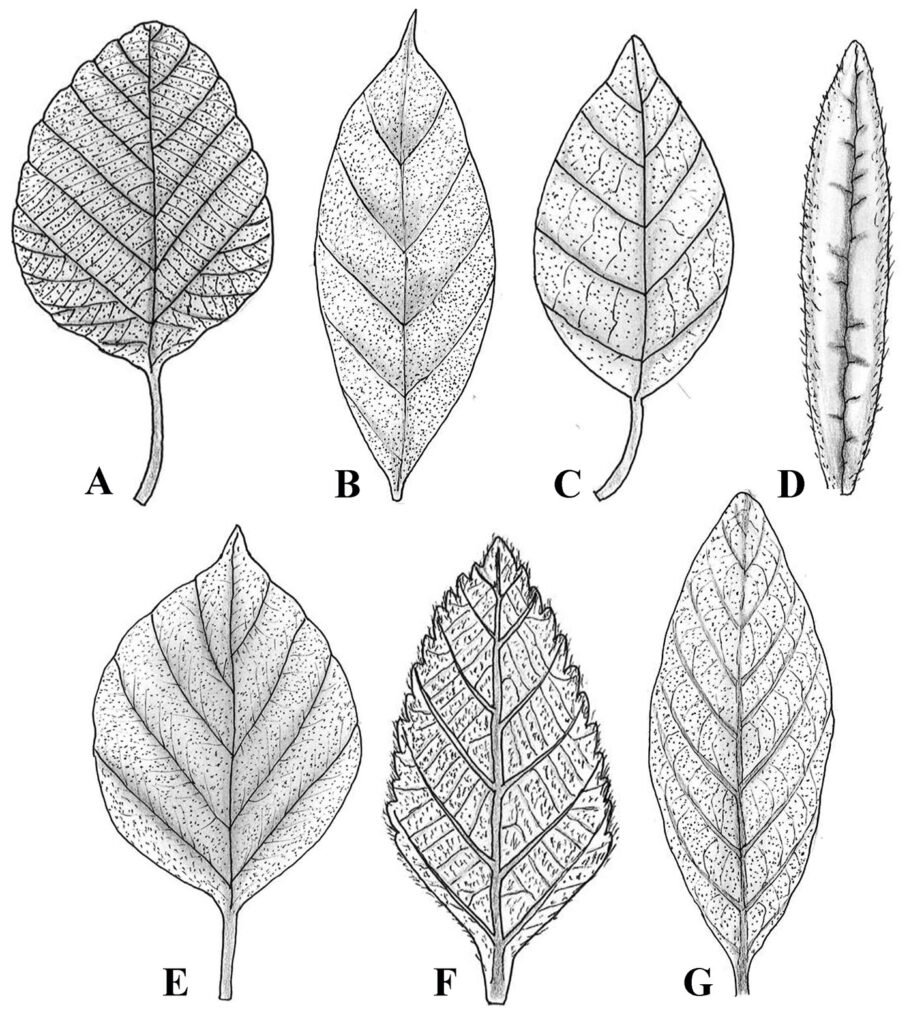

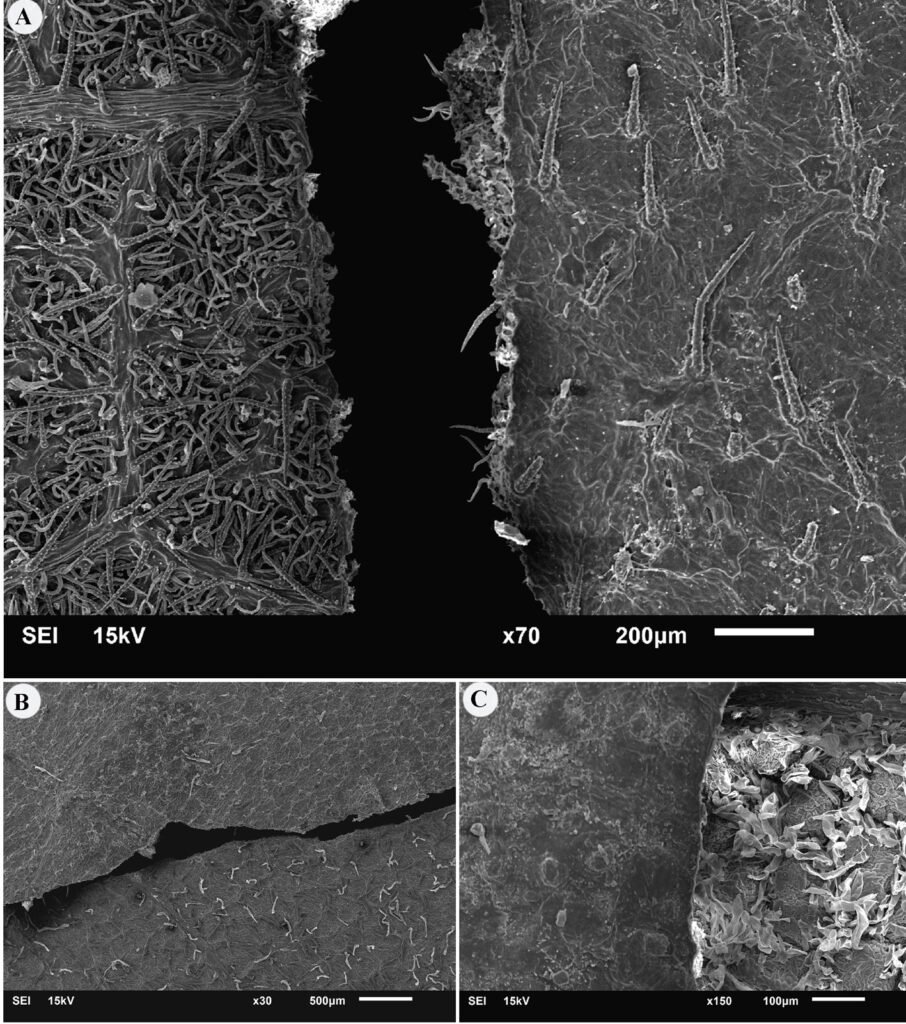

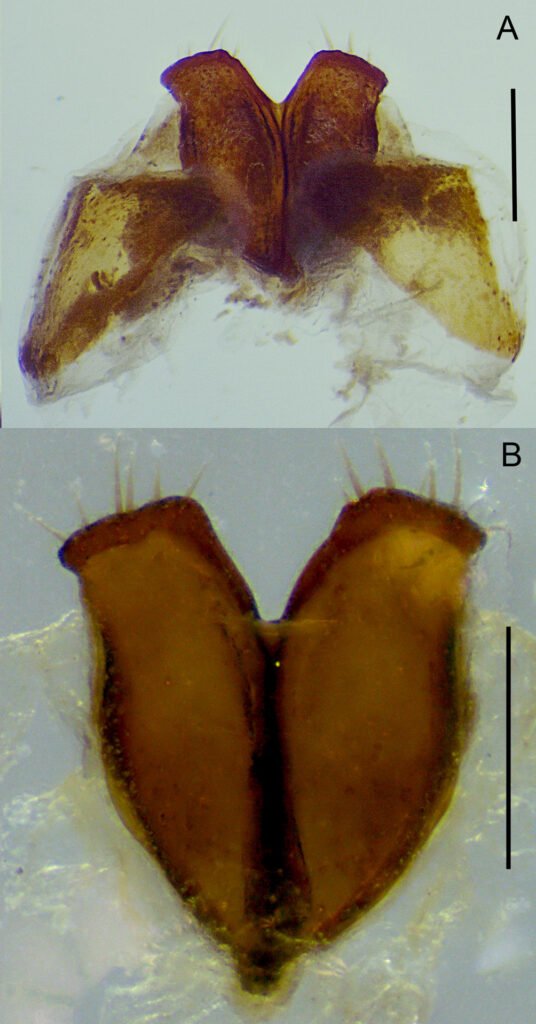

Diagnosis. Pupa boat-shaped, transverse molting suture reaches the submarginal line, dorsum and venter black, eye spots with tubercles, abdominal depressions present, middle area of abdominal segments smooth, abdominal VIII setae anterolateral to the vasiform orifice very small.

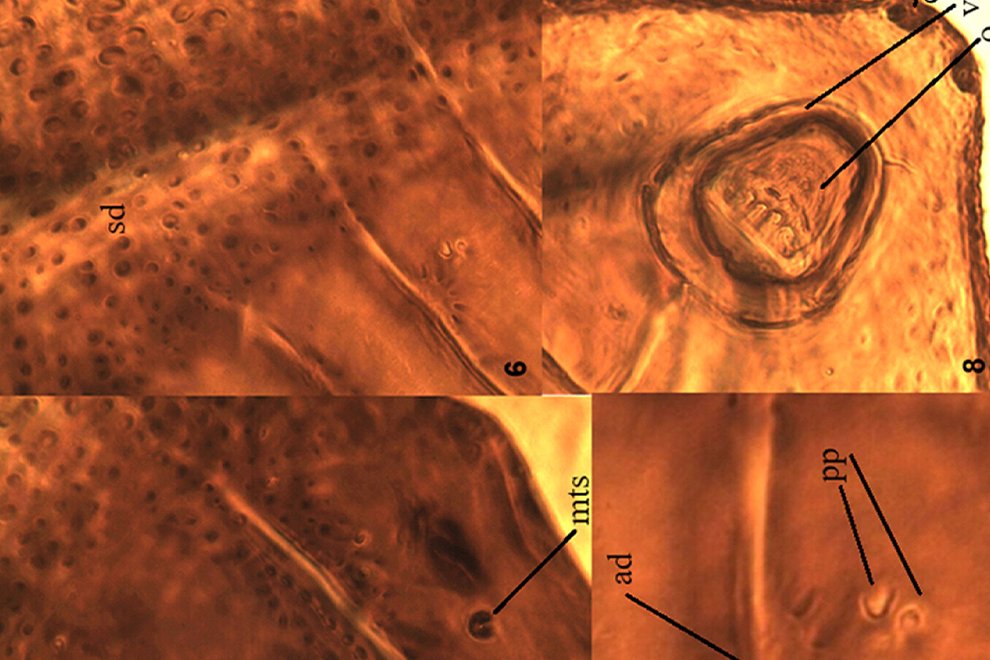

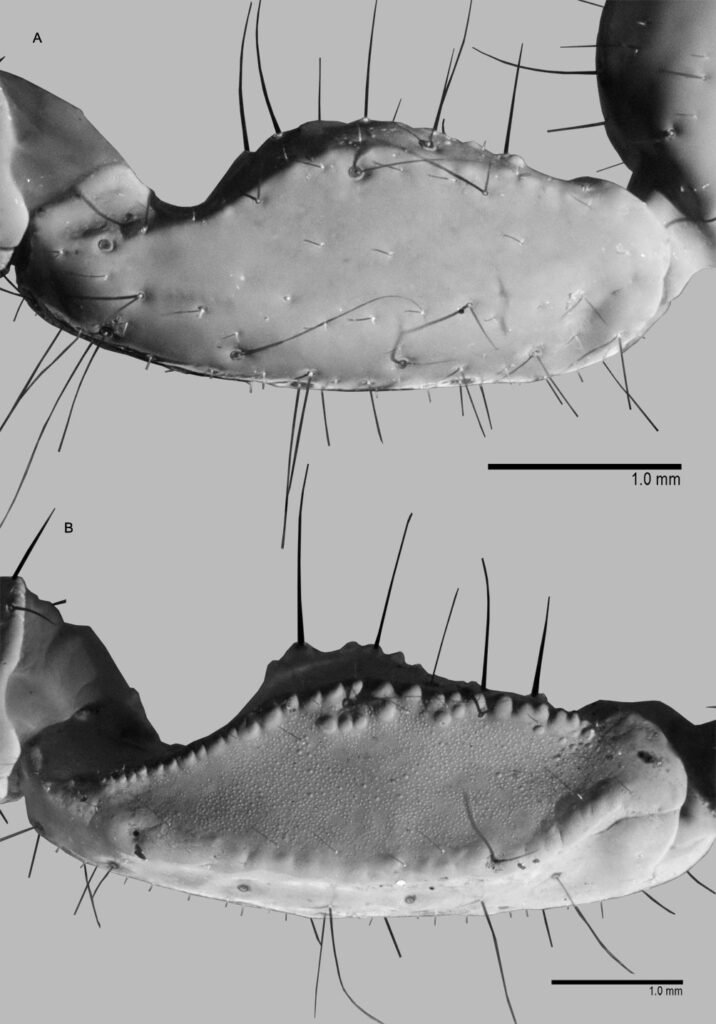

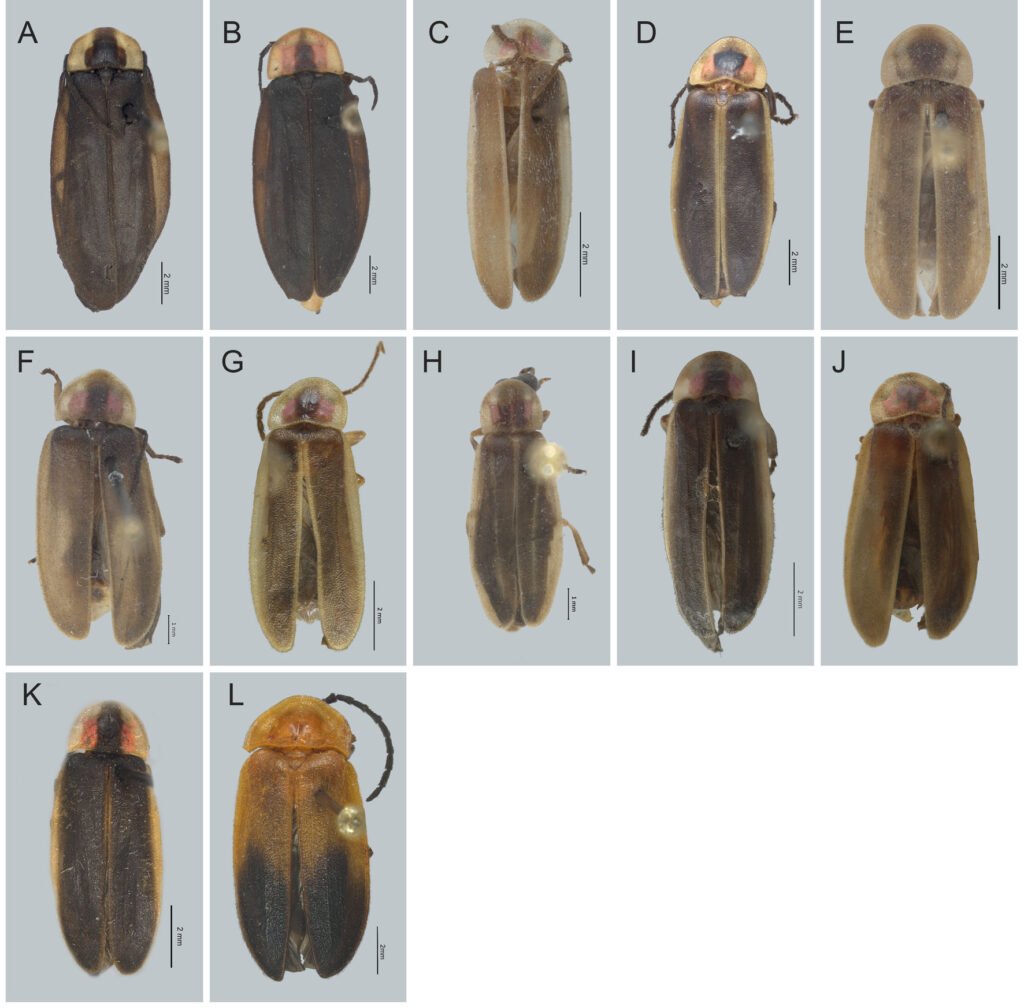

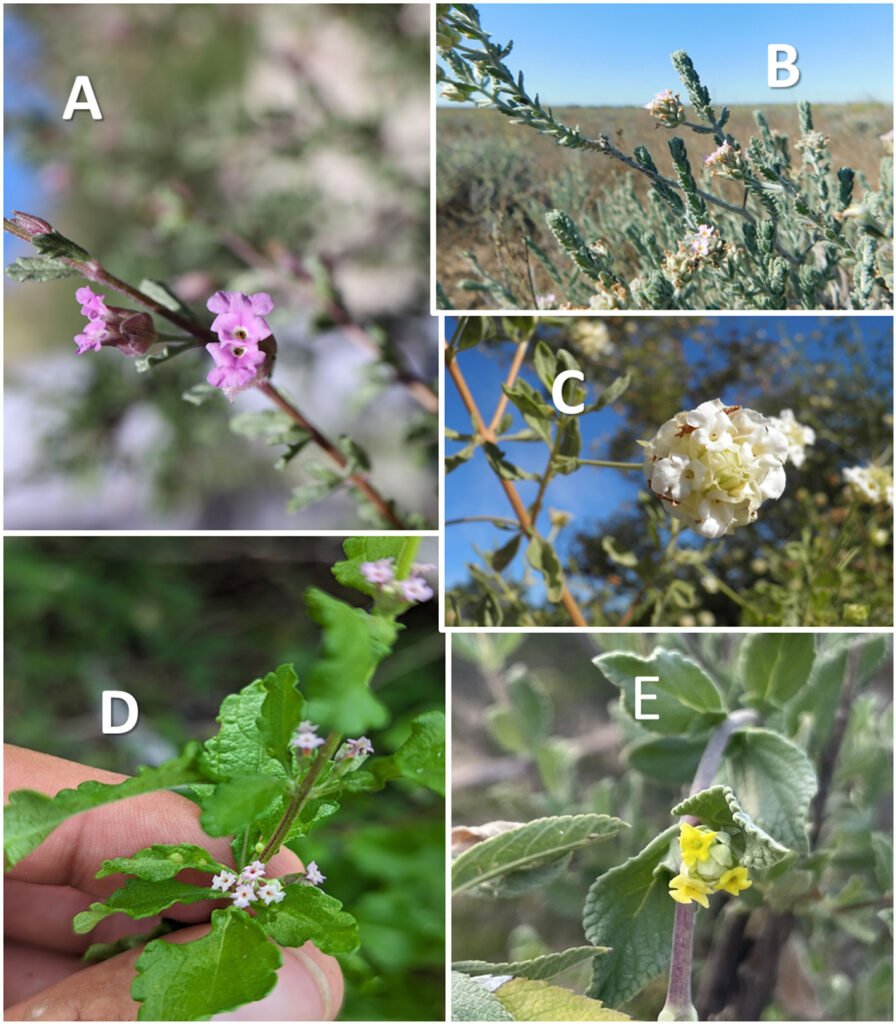

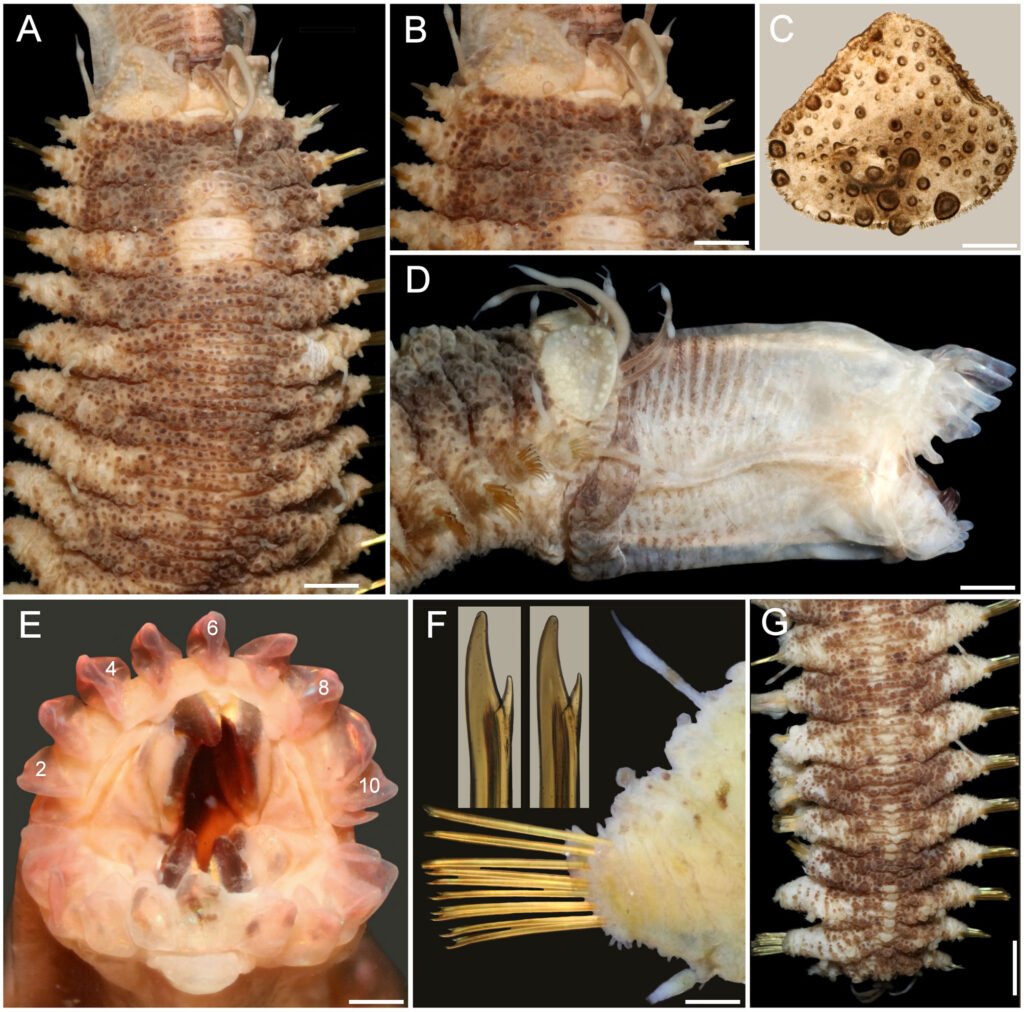

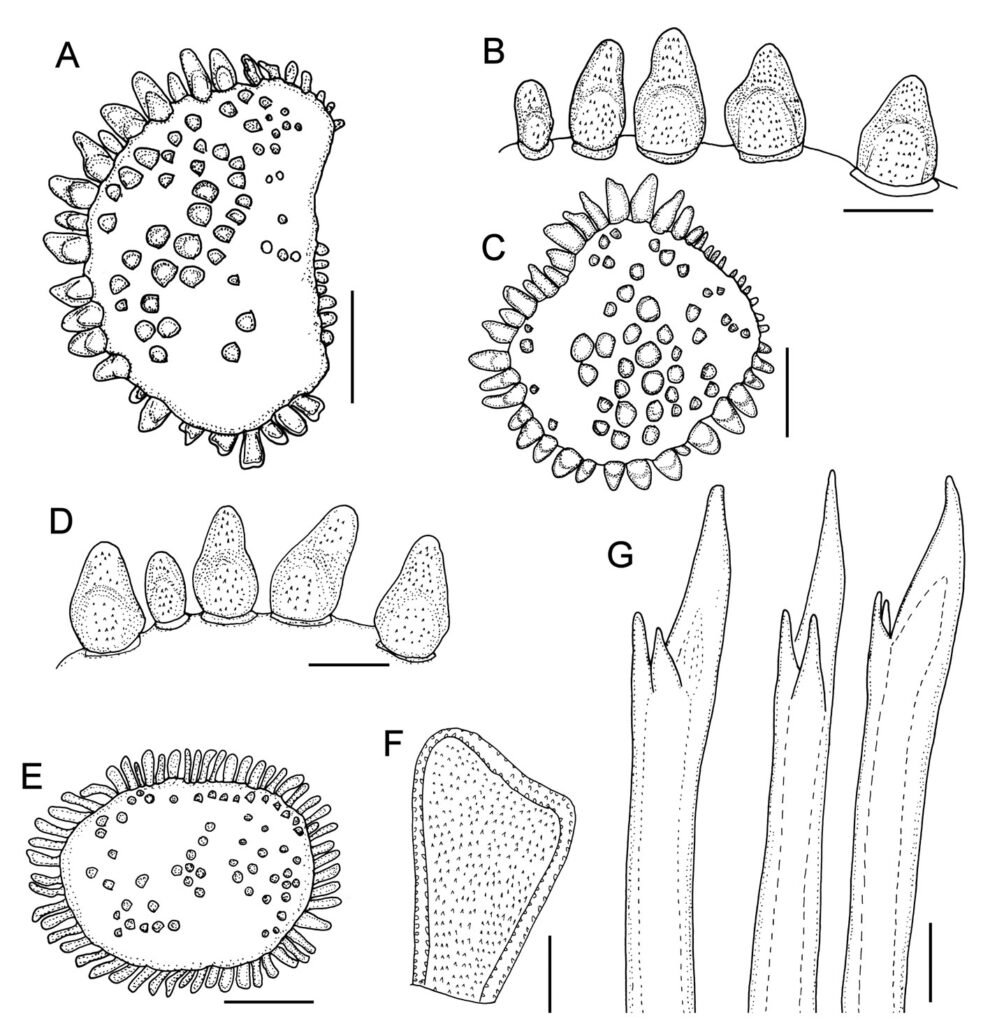

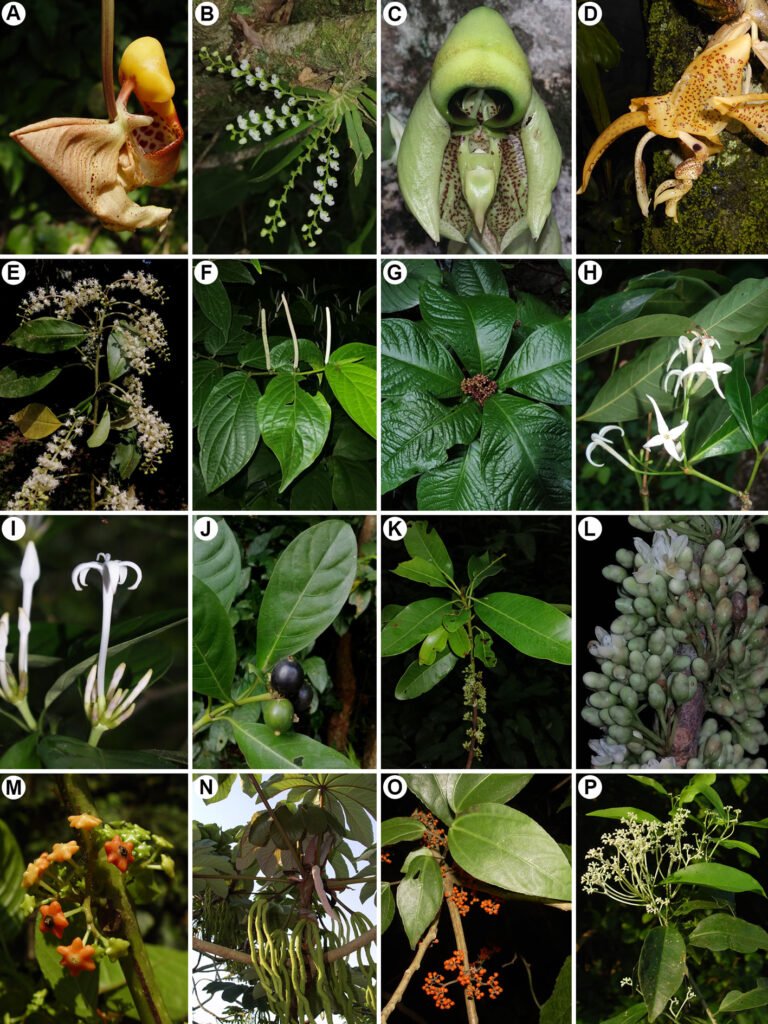

General form: pupae in situ. Dorsal and ventral surface of pupae black, a thin fringe of wax is distinguished around the body margin.

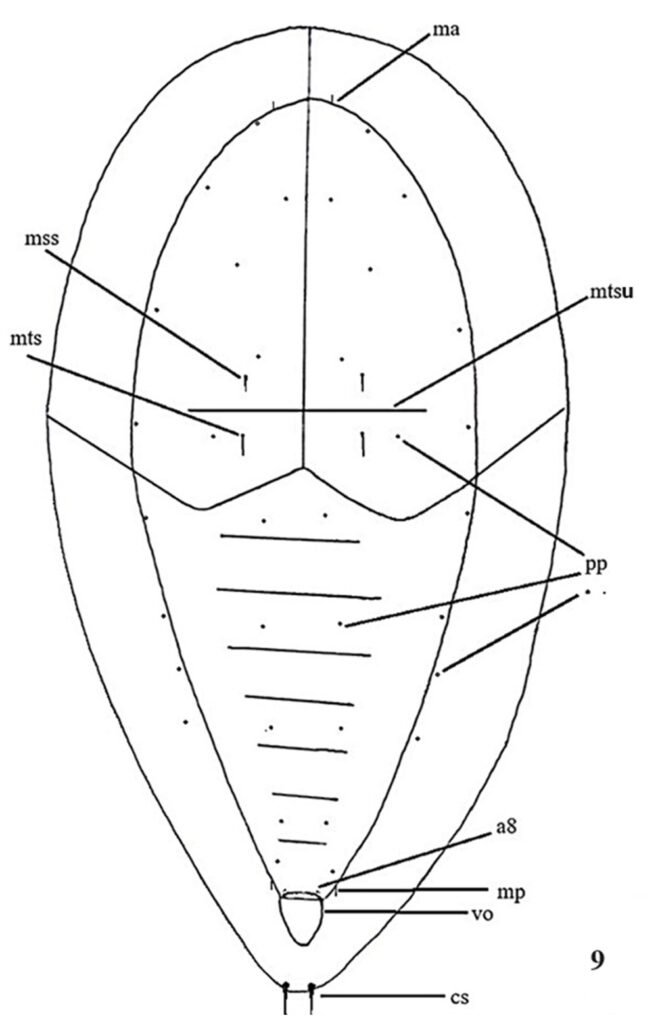

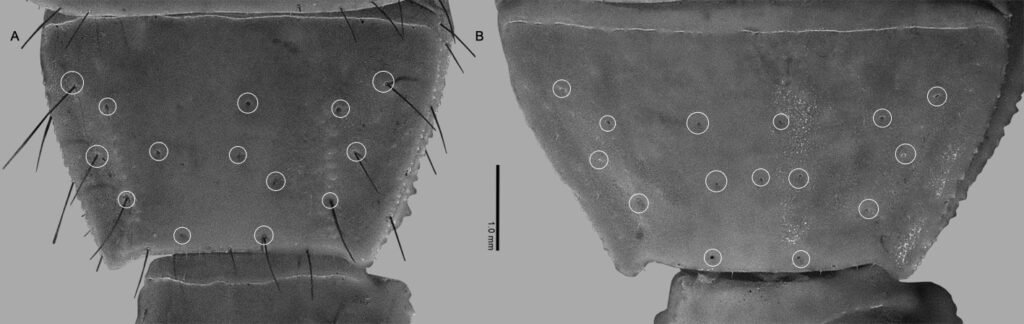

Specimens on slides: semioval body (Fig. 1). Deflexed submargin. Margin: with 61-68 pairs of marginal teeth with 2-3 acute terminal protrusions (Fig. 2), submargin with a regular band of small tubercles (Fig. 3); subdorsum: with a band of crescent tubercles (Fig. 4). Cephalothorax: longitudinal molting suture with a row of defined tubercles on each side giving the appearance of a zipper, transverse molting suture ends at the apparent margin (submarginal fold), well defined meso-metathoracic suture (Fig. 5), ocular markings (eye spots) indicated by pale coloration and 5-7 pairs of pale tubercles in the subdorsal area near the submarginal line, cephalic setae absent; mid thoracic zone with 2 pairs of setae, the mesothoracic and the metathoracic. Abdomen: dorsum with abdominal segments I-VIII clearly visible in the middle part (Fig. 6). With abdominal depressions in the middle area of the segments (Fig. 7), cuticle in the middle of the abdominal segments smooth. Vasiform orifice: elongated semicordiform (Fig. 8); elevated; operculum with 4 irregular longitudinal furrows and spinules at the apex, completely covering the lingula and most of the vasiform orifice, ring of the orifice defined in its anterior part, abdominal VIII setae anterolateral to the vasiform orifice very small, caudal protuberance developed. Pores, normally as follows: 8 pairs in the cephalic area, 6 on submedian area and 2 posterior to eye spots; 4 pairs in the mesothorax, 2 on submedian area and 2 in the subdorsal area of the mosothorax; medial area of abdominal segments I, III, V, VII with 2 pairs each segment, segment VIII with 2 pairs; subdorsal area of abdominal segments II, IV, V, with 2 pairs of pores in each segment (Fig. 9).

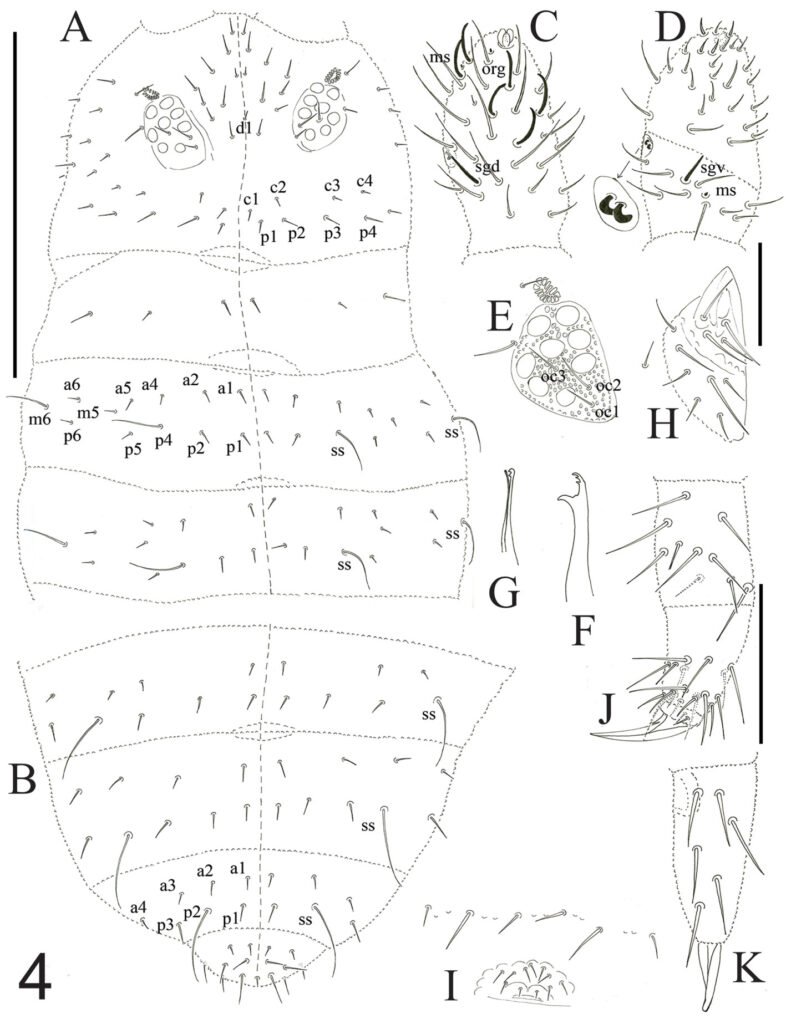

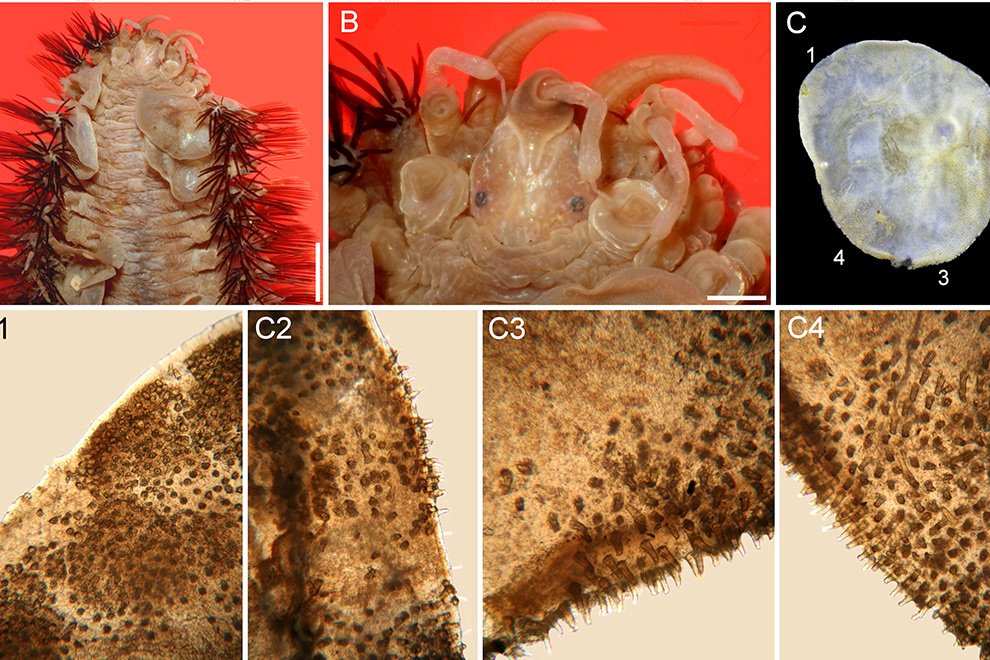

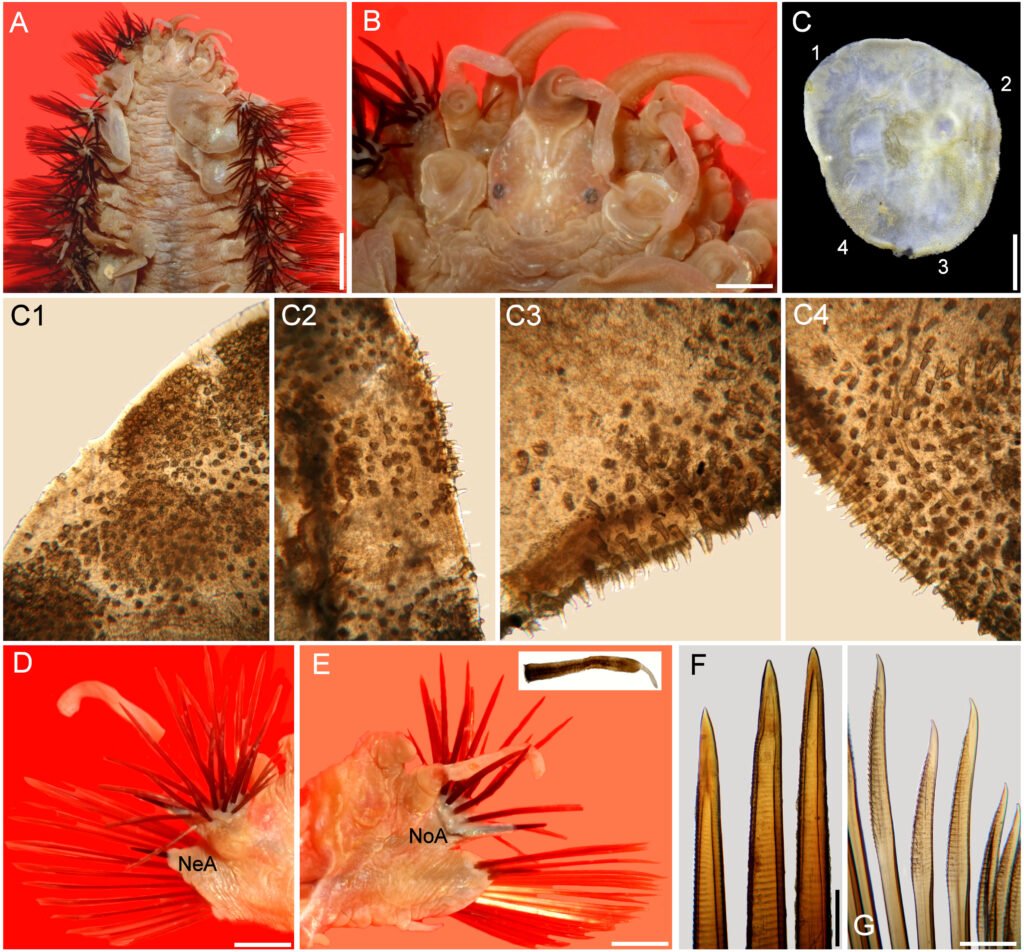

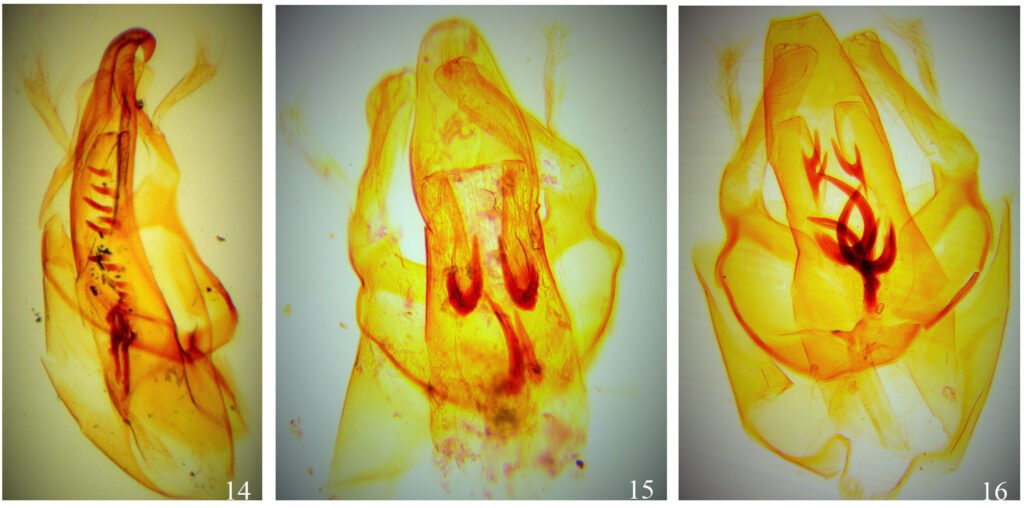

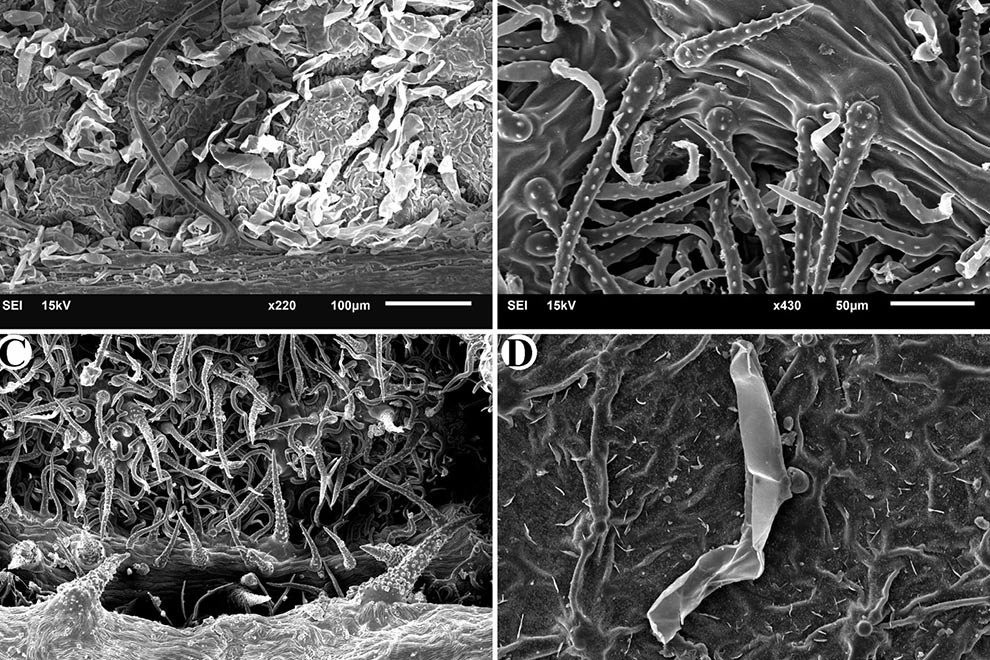

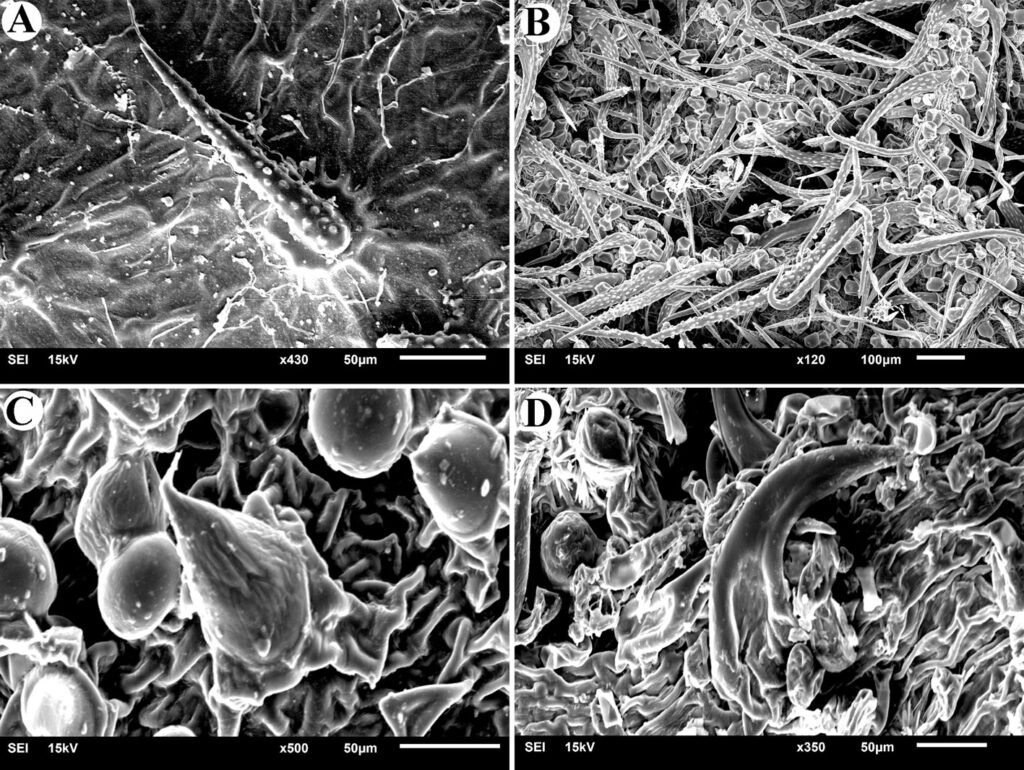

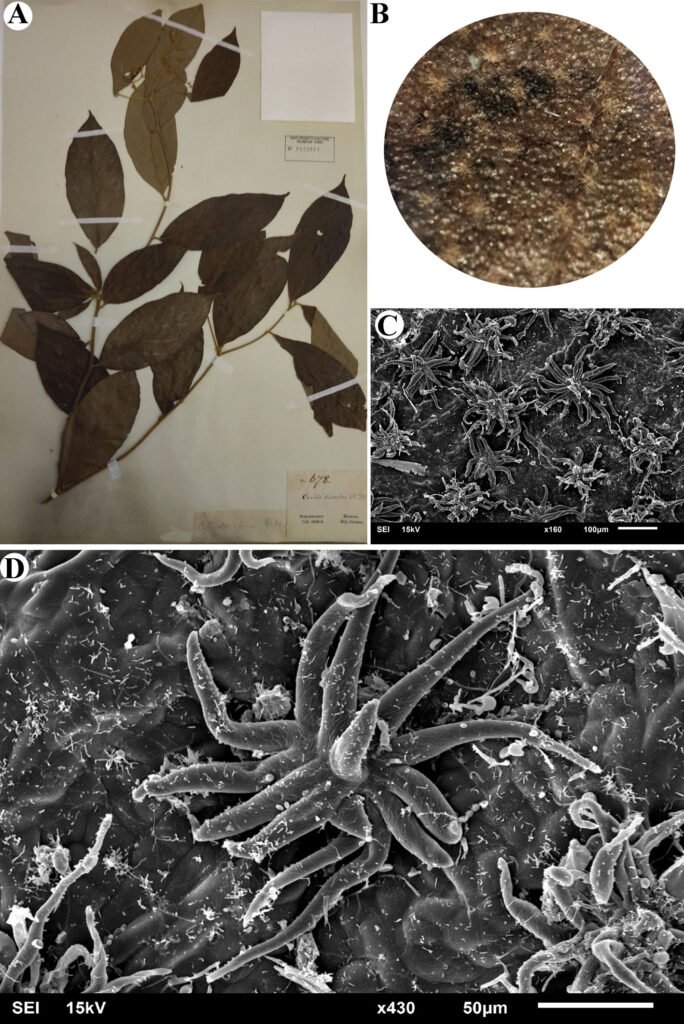

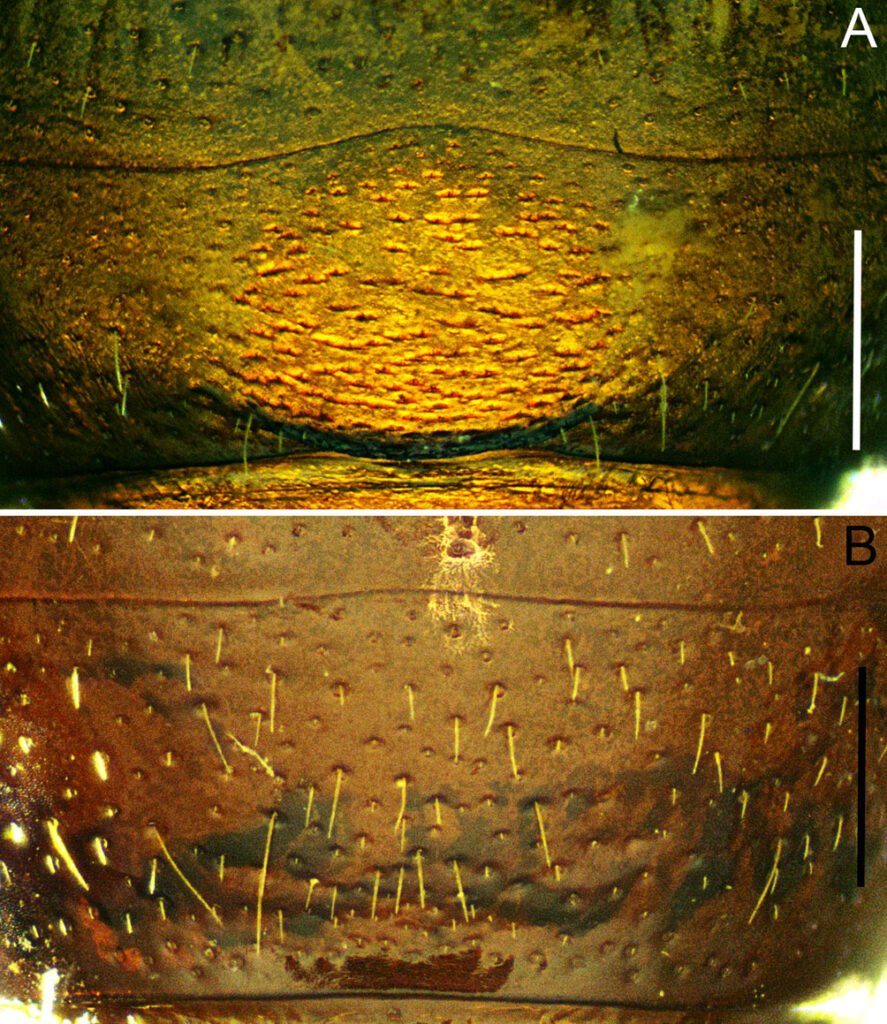

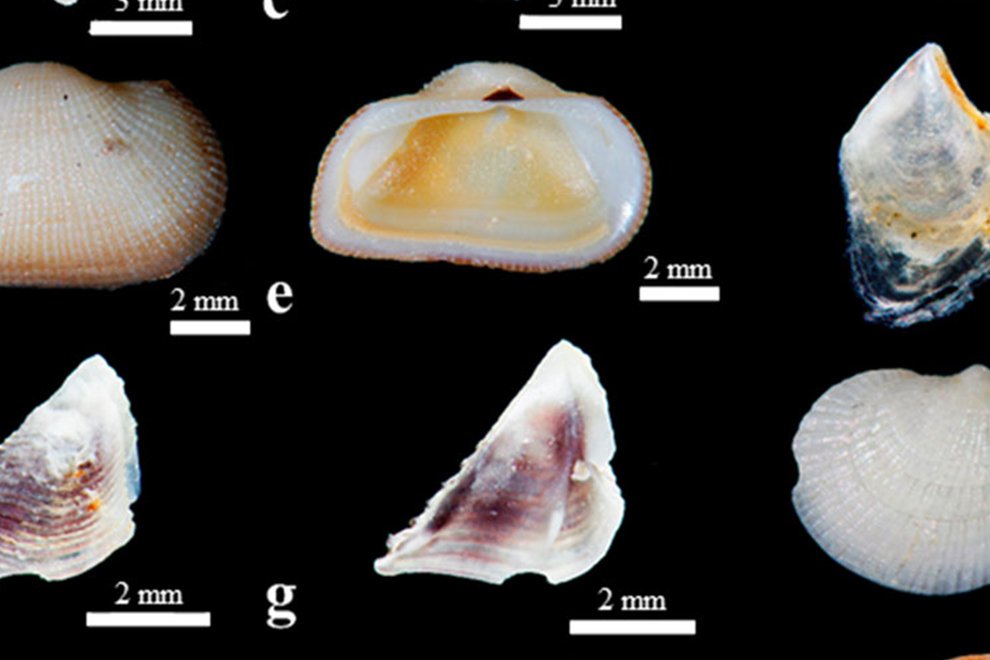

Figures 1-4. Aleuropleurocelus tecomastans.1) Puparium; 2) marginal teeth; 3) submarginal area; 4) subdorsal area. mt = Marginal teeth, om = ocular mark, sd = subdorsum, sm = submargin.

Venter: legs prothoracic, mesothoracic, metathoracic with apical adhesive sac, thoracic adhesive sacs near the base of the first pair of legs, base of the legs with a wide irregular band of 2-4 spinules, thoracic and abdomen cuticle smooth, well defined abdominal setae of segment VIII, posteriorly present a pair of spiracles. Chaetotaxy: a pair of anterior marginal setae present (near marginal teeth), cephalic setae absent, mesothoracic, metathoracic and caudal setae well developed, very small abdominal VIII setae, located anterolateral to the vasiform orifice, and posterior marginal setae small.

Figures 5-8. Aleuropleurocelus tecomastans.5) Thoracic area; 6) submedia and subdorsal area; 7) depression and pore of abdominal segment IV; 8) vasiform orifice. ad = Abdominal depression, cs = caudal seta, mss = mesothoracic seta, mts = metathoracic seta, o = operculum, pp = pore porete, sd = subdorsum, vo = vasiform orifice.

Measurements. Specimens on slides: body 550-650 µm long by 300-400 µm wide. Submargin approximately 45-55 μm. Cephalothorax: 230-280 μm, longitudinal molting suture, 240-360 μm, transverse molting suture 220-250 μm, the metathorax 30-45 μm long in its middle area, cephalic elongated structures of 8-10 µm long by 3-5 µm wide. Abdomen: abdominal segments length for segment I 22-26 μm, segment II 22-26 μm, segment III 25-30 μm, segment IV 26 -30 μm, segment V 27-32 μm, segment VI 26-29 μm, segment VII 23-27 μm, and segment VIII (from suture VII-VIII to vasiform orifice) 40-50 μm, distance from vasiform orifice to apparent margin 25-35 μm; abdominal depressions segments with approximate length in segment I 3-5 μm long by 10-12 μm wide, in segment II 3-4 μm long by 12-15 μm wide, in segment III 3-4 μm long by 10-13 μm wide, in segment IV 3-4 μm long by 10-14 μm wide, in segment V 5-7 μm long by 10-15 μm wide, in segment VI 5-6 μm long by 9-11 μm wide. Vasiform orifice: 46-50 µm long by 32-38 µm of broad at the widest part; operculum 25-30 μm long by 22-26 μm wide. Venter: Prothoracic legs 75-77 μm long, mesothoracic legs 75-78 μm long, metathoracic legs 85-89 μm long, thoracic adhesive sacs of 16-20 μm in diameter, base of the legs spinules 4 μm long and 2 μm wide. Setae: anterior marginal setae approximately 7 μm long, mesothoracic setae approximately 15 μm long, metathoracic setae approximately 20 μm long, abdominal VIII setae 3-4 μm long, caudal seta approximately 20 μm long, and posterior marginal seta approximately 10 μm long.

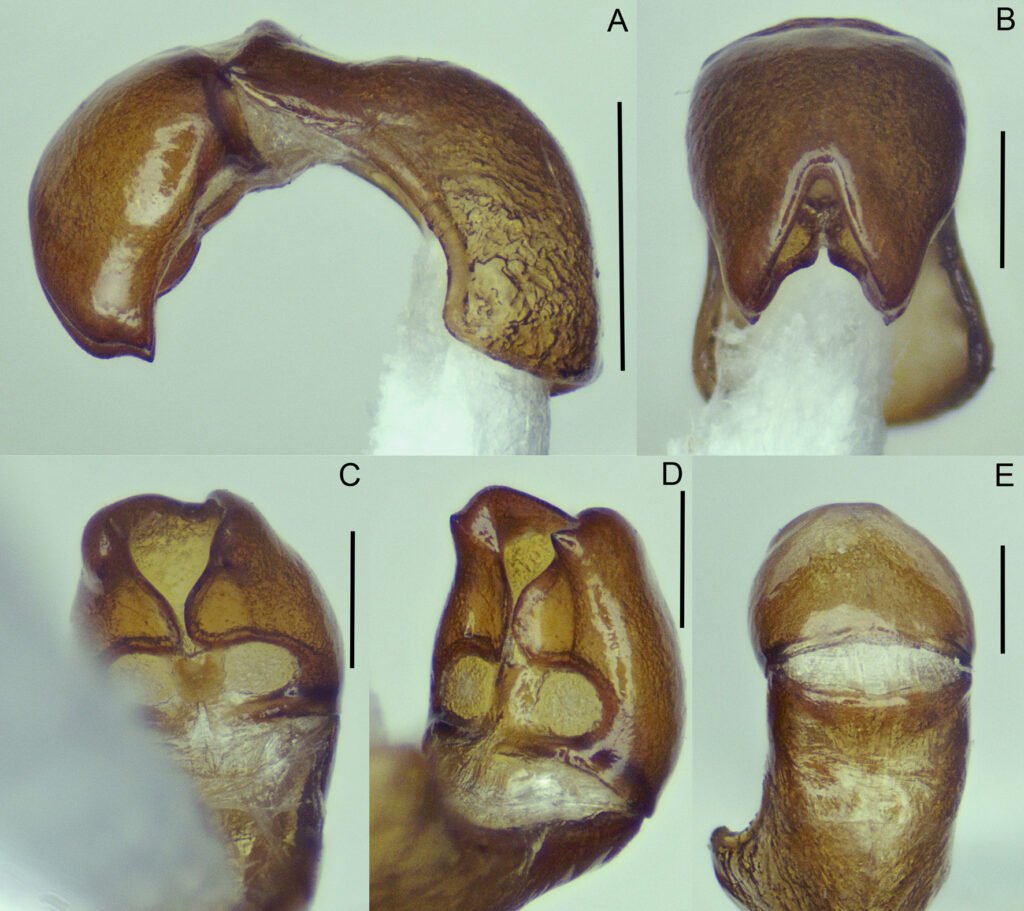

Figure 9. Aleuropleurocelus tecomastans. Pores and setae distribution. a8 = VIII abdominal segment seta, cs = caudal seta, ma = marginal anterior seta, mp = marginal posterior seta, mss = mesothoracic seta, mts = metathoracic seta, mtsu = metathoracic suture, pp = pore porete, vo = vasiform orifice.

Taxonomic summary

Type locality: northeast of Acapulco, Guerrero, Mexico

Type material: holotype, puparium: Acapulco, Guerrero, Mexico, in leaves of Tecoma stans (Bignoniaceae), 8-iv-2021, Col. V. E. Carapia-Ruiz, deposited in CNIN (Colección Nacional de Insectos, Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City, Mexico), HOM-TIP-170. Paratypes: puparia, same data as holotype, 2 deposited in CNIN, HOM-PAR-171, HOM-PAR-172.

Etymology: the suffix name is based on a combination of the host plant’s scientific name where specimens were associated.

Distribution: Acapulco, Guerrero, Mexico.

Plant associations: Tecoma stans (Bignoniaceae).

Remarks.

Aleuropleurocelus tecomastans is placed within the ceanothi group by the transverse molting suture reaches the apparent margin (submarginal line). The new species is similar in apparence to A. granulate, A. sampsoni,and A. pseudogranulata but can be differentiated by the presence of abdominal depressions which is opposite as shown in A. granulata, A. sampsoni, A. pseudogranulata or A. ceanothi. Also A. asciculatus presents a subdorsal fold which is absent in the other species.

Key to species of Aleuropleurocelus group ceanothi

1. With bands of dense wax on dorsum, pores of double wall on dorsum 2

—Without such bands or pores 3

2. (1) Two bands of dense wax on dorsum (1 thin band on subdorsum and 1 wide band on submedian area ornatus Drews & Sampson

— One band of dense wax on subdorsum sampsoni Sánchez Flores & Carapia-Ruiz

3. (1) Tubercles on submedian surface absent 4

—Tubercles on submedian surface present 8

4. (3) Without evident tubercles on subdorsal surface 5

— With evident tubercles on subdorsal surface 6

5. (4) Longitudinal suture of the molt with tubercles on metathorax laingi Drews & Sampson

— Longitudinal suture of the molt without tubercles on metathorax coachellensis Drews & Sampson

6. (4) Subdorsal fold absent 7

— Subdorsal fold present asciculatus Carapia-Ruiz

7. (6) 2 pair of thoracic adhesive sacs, submarginal band with pores erigonium Carapia-Ruiz

— Without tubercles on the anterior and posterior part of the abdominal segments, abdominal depressions present tecomastans n. sp.

8. (3) With 2 pairs of thoracic adhesive sacs, submedian area with tubercles only on the anterior part of the abdominal segments; marginal teeth without 2 or more evident prostructions 9

— With a pair of thoracic adhesive sacs, submedian area with tubercles on the anterior and posterior part of the abdominal segments; marginal teeth with evident prostructions; transversal suture of the molt curved 10

9. (8) Half posterior of puparium in elliptic form sierra (Sampson)

— Half posterior of puparium in triangular form ceanothi (Sampson)

10. (8) Vasiform orifice semicircular, venter of abdomen with posterior area very narrow, transversal suture of the molt almost straight on median area granulata Sampson & Drews

— Vasiform orifice elongated, clearly more long than wide, venter of abdomen with posterior area triangular in form, transversal suture of the molt curved on median area pseudogranulata Carapia-Ruiz

Acknowledgments

To Paul Brawn and David Ovread of the British Museum of Natural History (BMNH) for facilitating a loan of Aleuropleurocelus to study the specimens.

References

Carapia-Ruiz, V. E. (2020a). Descripción de una especie nueva del género Aleuropleurocelus y nuevos registros para Baja California, México. Southwestern Entomologist, 45, 269–274. https://doi.org/10.3958/059.045.0128

Carapia-Ruiz, V. E. (2020b). Description of a new species of the genus Aleuropleurocelus Drews & Sampson (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) and a new country record for a species of the genus from Mexico. Acta Zoológica Mexicana (nueva serie), 36, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.21829/azm.2020.3612184

Carapia-Ruiz, V. E. (2023). Dos especies nuevas de Aleuro-

pleurocelus de México, Southwestern Entomologist, 48, 641-648. https://doi.org/10.3958/059.045.0425

Carapia-Ruiz, V. E., & Sánchez-Flores, O. A. (2019a). Descripción de una especie nueva del género Aleuropleurocelus Drews y Sampson (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) de California, Estados Unidos. Acta Zoológica Mexicana (nueva serie), 35, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.21829/azm.2019.3501230

Carapia-Ruiz, V. E., & Sánchez-Flores, O. A. (2019b). Descripción de la primera especie pálida del género Aleuropleurocelus. Southwestern Entomologist, 44, 315–319. https://doi.org/10.3958/059.044.0133

Carapia-Ruiz, V. E., Sánchez-Flores, O. A., & García-Ochaeta, J. F. (2023). A new whitefly species, Aleuropleurocelus petenensis sp. nov. (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae), from Guatemala. Acta Zoológica Mexicana (nueva serie), 39, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.21829/azm.2023.3912470

Carapia-Ruiz, V. E., Sánchez-Flores, O. A., García-Martínez, O., & Castillo-Gutiérrez, A. (2018a). Descripción de dos especies nuevas del género Aleuropleurocelus Drews y Sampson, 1956 (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) de México. Insecta Mundi, 0606, 1–13.

Carapia-Ruiz, V. E., Sánchez-Flores, O. A., García-Martínez, O., & Castillo-Gutiérrez, A. (2018b). Descripción de dos especies nuevas del género Aleuropleurocelus Drews y Sampson, 1956 (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) de México. Southwestern Entomologist, 43, 517–526.

Carapia-Ruiz, V. E., Sánchez-Flores, O. A., García-Martínez, O., & Castillo-Gutiérrez, A. (2021). Aleuropleurocelus palidonigrans sp. nov. de Guerrero, México, Southwestern Entomologist, 46, 781–786. https://doi.org/10.3958/059.046.

0320

Dooley, J. W., Lambrecht, S., & Honda, J. (2010). Eight new state records of aleyrodine whiteflies found in Clark County, Nevada and three newly described taxa (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae, Aleyrodinae). Insecta Mundi, 140, 1−36.

Drews, E. A., & Sampson, W. W. (1956). Tetralicia and a new related genus Aleuropleurocelus (Homoptera: Aleyrodidae). Annals Entomological Society of America, 49, 280–283. https://doi.org/10.1093/aesa/49.3.280

Drews, E. A., & Sampson, W. W. (1958). California aleyrodids of the genus Aleuropleurocelus. Annals of the Entomological Society of America, 51, 120–125.

Martin, J. H. (2004). The whiteflies of Belize (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) Part 1 — Introduction and account of the subfamily Aleurodicinae Quaintance and Baker. Zootaxa, 681, 1–119. https://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.681.1.1

Martin, J. H. (2005). Whiteflies of Belize (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae). Part 2 — A review of the subfamily Aleyrodinae Westwood. Zootaxa, 1098, 1–116. https://dx.

doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.1098.1.1

Polaszek, A., & Gill, R. (2011). A new species of whitefly (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) and its parasitoid (Hymenoptera: Aphelinidae) from desert lavender in California. Zootaxa, 2750, 51–59. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.2150.1.5/biota

xa.org

Sánchez-Flores, O. A., & Carapia-Ruiz, V. E. (2018a). Nueva especie de Aleuropleurocelus Drews y Sampson (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) y clave para especies del grupo de forma oval. Insecta Mundi, 651, 1–12.

Sánchez-Flores, O. A., & Carapia-Ruiz, V. E. (2018b). Description of two new species of the genus Aleuropleurocelus Drews y Sampson (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) from Mexico. Acta Zoológica Mexicana (nueva serie), 34, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.21829/azm.2018.3412145

Sánchez-Flores, O. A., Carapia-Ruiz, V. E., Coronado-Blanco, J. M., & Ruíz-Cancino, E. (2020). Description of Aleuropleurocelus sampsoni sp. nov. (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) from Tamaulipas, Mexico. Florida Entomologist, 103, 274–280. https://doi.org/10.1653/024.103.0219

Sánchez-Flores, O. A., Carapia-Ruiz, V. E., García-Martínez, O., & Castillo-Gutiérrez, A. (2018a). Descripción de una especie nueva del género Aleuropleurocelus de México. Southwestern Entomologist, 43, 257–262. https://doi.org/

10.3958/059.043.0116

Sánchez-Flores, O. A., Carapia-Ruiz, V. E., García-Martínez, O., & Castillo-Gutiérrez, A. (2018b). Descripción de una especie nueva del género Aleuropleurocelus (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) de México. Acta Zoológica Mexicana (nueva serie), 34, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.21829/azm.2018.3412104

Sánchez-Flores, O. A., García-Ochaeta, J. F., Carapia-Ruiz, V. E., Ruiz-Cancino, E., & Coronado-Blanco, J. M. (2021). New species of Aleuropleurocelus Drews and Sampson (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) from Guatemala, with a key to species from the oval group. Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington, 123, 615–621. https://doi.org/10.4289/0013-8797.123.3.614

A multigene approach to identify the scorpion species (Arachnida: Scorpiones) of Colima, Mexico, with comments on their venom diversity

Edmundo González-Santillán a, Laura L. Valdez-Velázquez b, *, Ofelia Delgado-Hernández c, Jimena I. Cid-Uribe d, María Teresa Romero-Gutiérrez e, Lourival D. Possani d

a Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Biología, Departamento de Zoología, Colección Nacional de Arácnidos, Tercer Circuito Exterior s/n, Ciudad Universitaria, Coyoacán, 04510 Ciudad de México, Mexico

b Universidad de Colima, Facultad de Ciencias Químicas y Facultad de Medicina, Km 9 Carretera Colima-Coquimatlán, 28400 Coquimatlán, Colima, Mexico

c Instituto Francisco Possenti, Av. Toluca 621, Olivar de los Padres, Álvaro Obregón, 01780 Mexico City, Mexico

d Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Biotecnología, Avenida Universidad 2001, Colonia Chamilpa, 62210 Cuernavaca, Morelos, Mexico

e Universidad de Guadalajara, Centro Universitario Tlajomulco, Departamento de Innovación Tecnológica, Carretera Tlajomulco – Santa Fé Km. 3.5 No.595 Lomas de Tejeda, 45641 Tlajomulco de Zúñiga, Jalisco, Mexico

*Corresponding author: lauravaldez@ucol.mx (L.L. Valdez-Velázquez)

Received: 9 October 2023; accepted: 19 March 2024

Abstract

Scorpion species diversity in Colima was investigated with a multigene approach. Fieldwork produced 34 lots of scorpions that were analyzed with 12S rDNA, 16S rDNA, COI, and 28S rDNA genetic markers. Our results confirmed prior phylogenetic results recovering the monophyly of the families Buthidae and Vaejovidae, some species groups, and genera. We recorded 11 described species of scorpions and found 3 putatively undescribed species of Centruroides, 1 of Mesomexovis, and 1 of Vaejovis. Furthermore, we obtained evidence that Centruroides elegans, C. infamatus,and C. limpidus do not occur in Colima, contrary to prior reports. Seven genetically different and medically relevant species of Centruroides for Colima are recorded for the first time. We used the InDRE database (Instituto de Diagnóstico y Referencia Epidemiológicos), which contains georeferenced points of scorpions, to estimate the distribution of the scorpion species found in our fieldwork. Finally, we discuss from a biogeographical, ecological, and medical point of view the presence and origin of the 14 scorpion species found in Colima.

Keywords: Barcoding; Holotype; Medical relevance; Microendemic; New species; Species group; Substrate-specialist

© 2024 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Biología. Este es un artículo Open Access bajo la licencia CC BY-NC-ND

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Una aproximación multigenes para identificar a las especies de alacranes (Arachnida: Scorpiones) de Colima, México, con cometarios sobre la diversidad de sus venenos

Resumen

La diversidad de especies de alacranes de Colima se investigó utilizando una aproximación multigenes. Del trabajo de campo se obtuvieron 34 lotes de alacranes que fueron analizados con los marcadores 12S rDNA, 16S rDNA, COI, y 28S rDNA. La comparación con trabajos de filogenia previos nos permitió confirmar la monofilia de las familias Buthidae y Vaejovidae, de algunos grupos de especies y géneros. Encontramos 11 especies de alacranes descritas, 3 putativamente nuevas de Centruroides, 1 de Mesomexovis y 1 de Vaejovis. También obtuvimos evidencia de que Centruroides elegans, C. infamatus y C. limpidus no están distribuidos en Colima, como se registró en trabajos anteriores. Reportamos 7 especies genéticamente distintas y de importancia médica para Colima. Usamos la base de datos del InDRE (Instituto de Diagnóstico y Referencia Epidemiológicos) que contiene puntos georreferenciados de alacranes para estimar la distribución de las especies que recolectamos en el campo. Finalmente, discutimos desde una perspectiva biogeográfica, ecológica y de importancia médica las 14 especies de alacranes que reportamos para Colima.

Palabras clave: Código de barras; Holotipo; Importancia médica; Microendémico; Especie nueva; Grupo de especies; Sustrato-especialista

Introduction

The knowledge of scorpion diversity in North America has improved recently (González-Santillán & Prendini, 2013; Goodman, Prendini, Francke et al., 2021; Ponce-Saavedra & Francke, 2019; Santibáñez-López et al., 2014); however, much remains to be discovered. Local-scale inventories may be a solution to unveil species communities that, in turn, can help conform regional faunas. This approach has rarely been applied to study scorpion diversity. Furthermore, few local faunal studies have been conducted in Mexico, and only a handful of them have been published; other revisionary contributions included limited fieldwork effort (Baldazo-Monsivais et al., 2012, 2016, 2017).

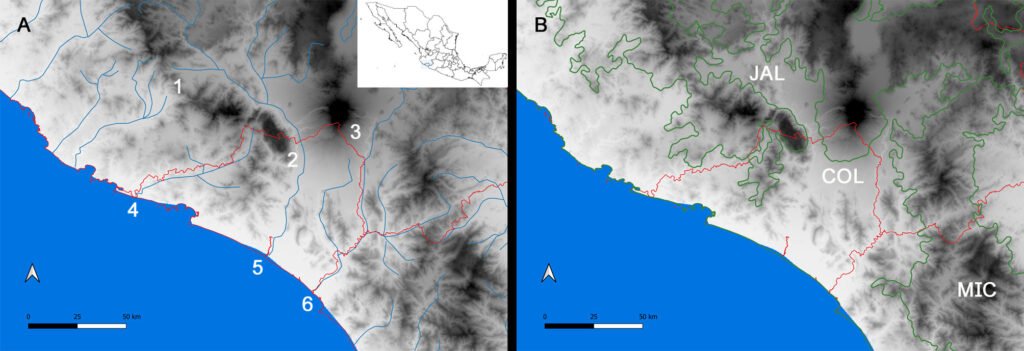

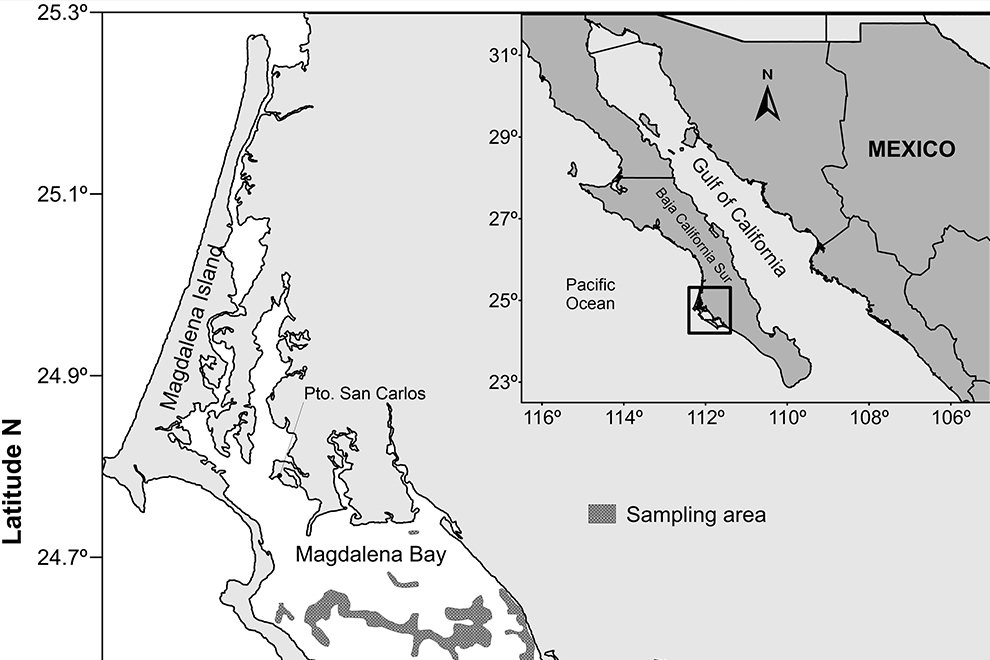

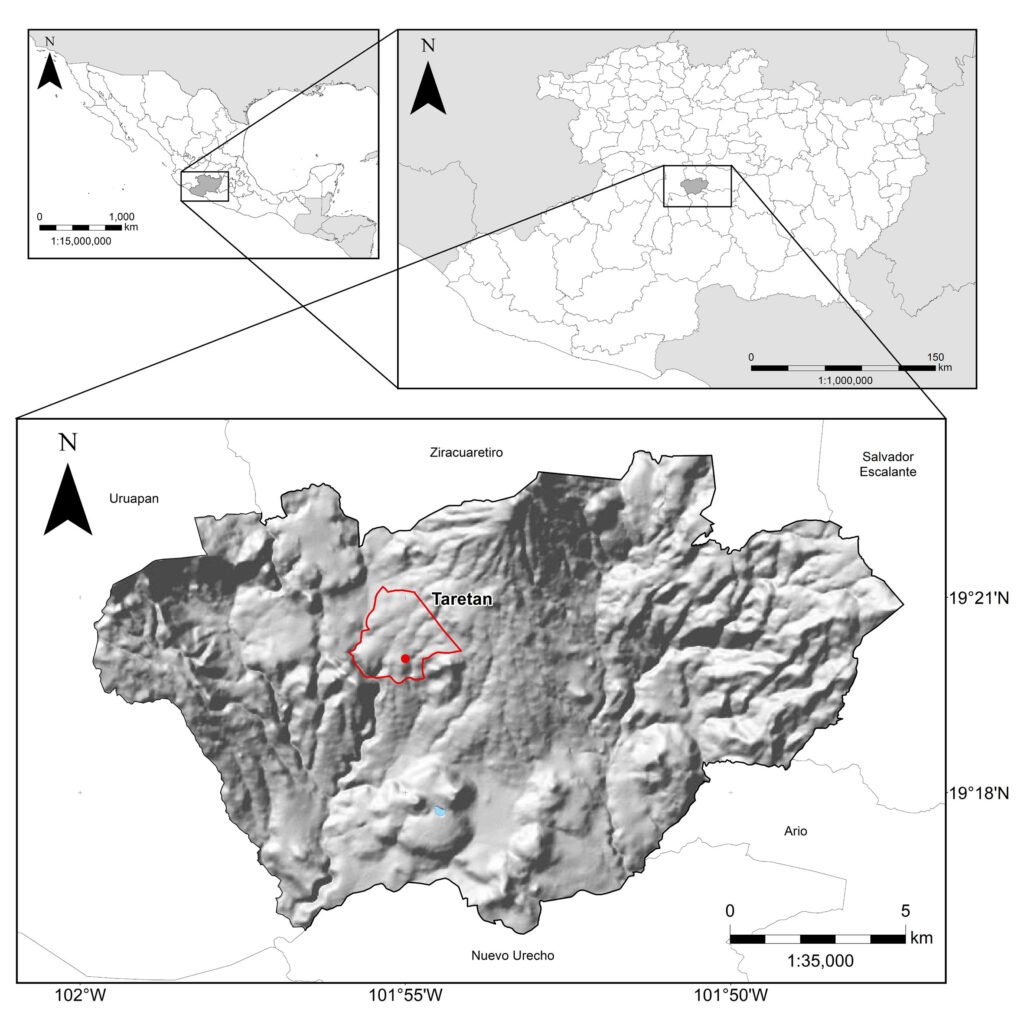

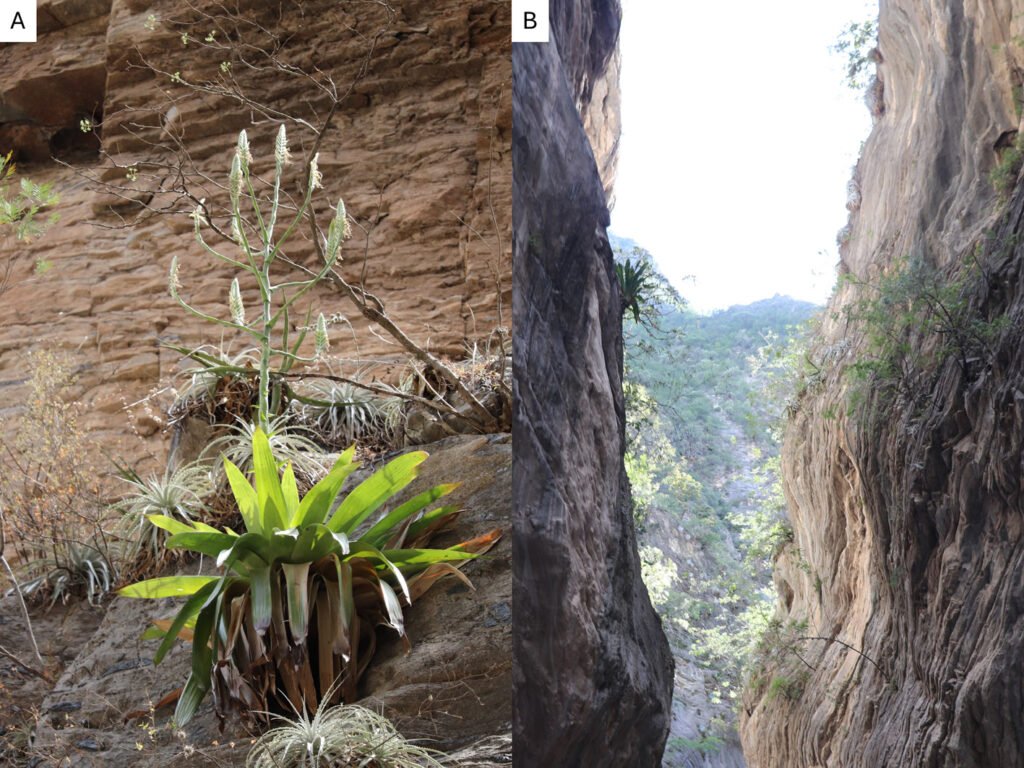

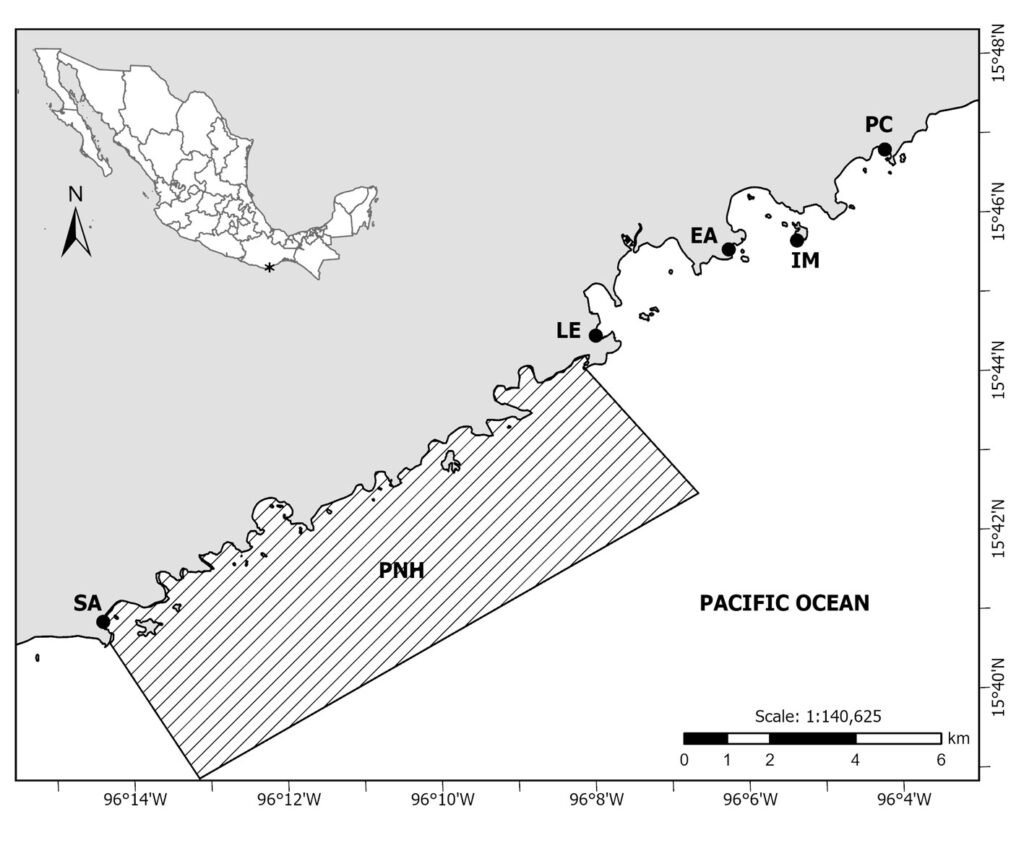

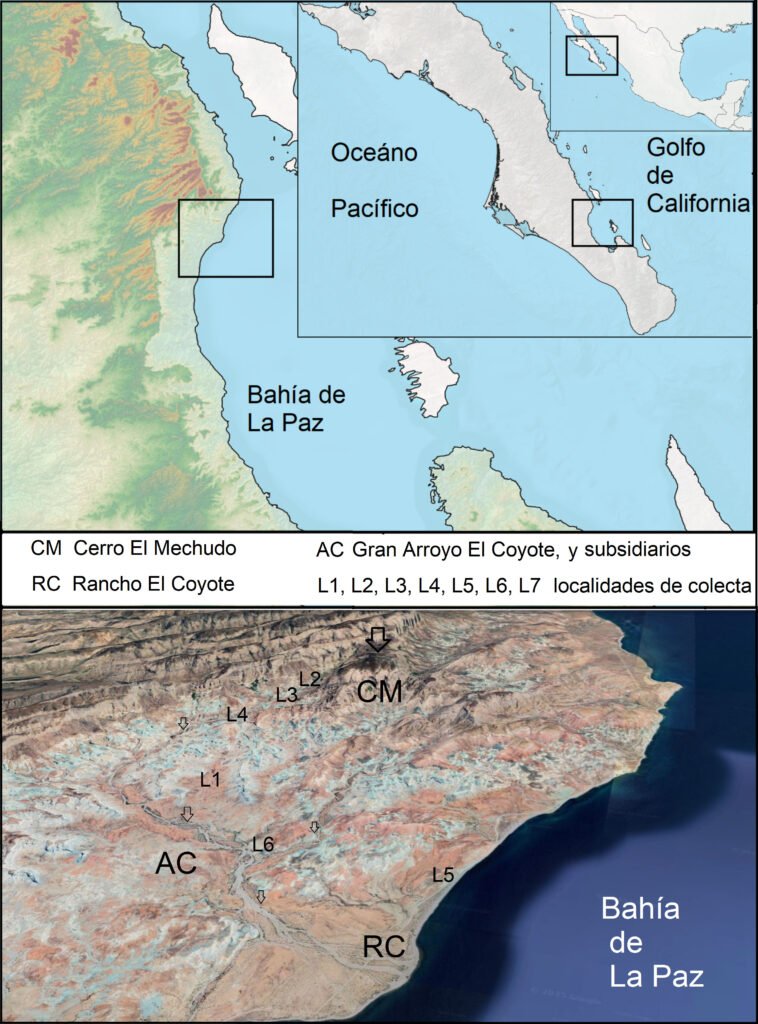

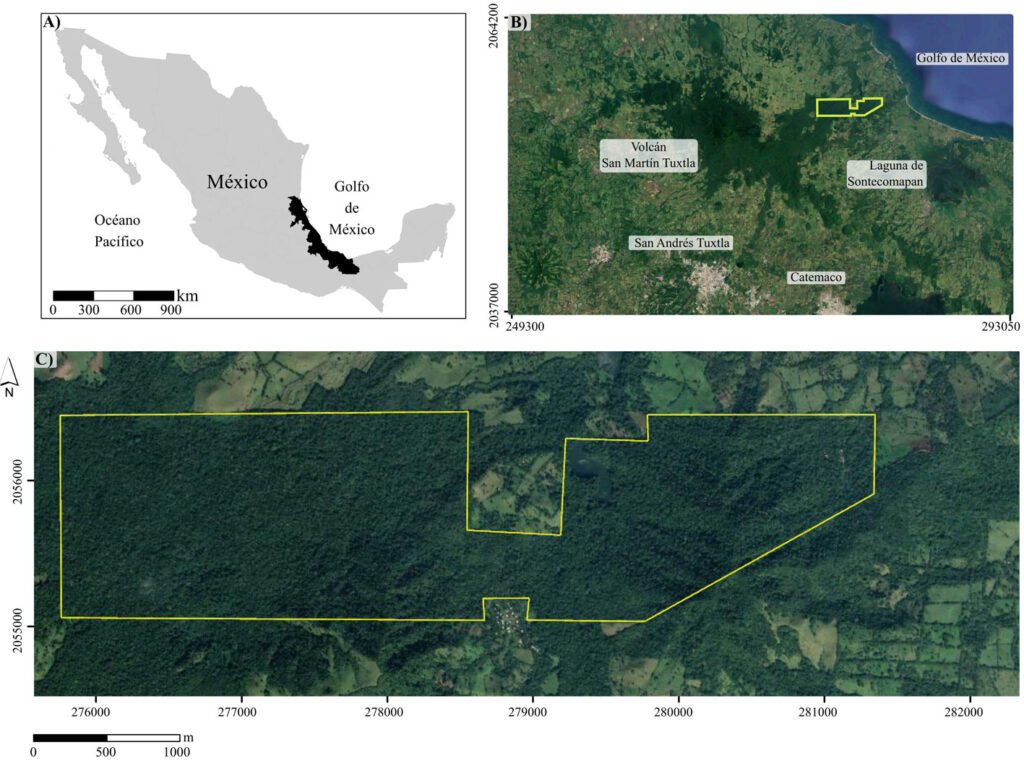

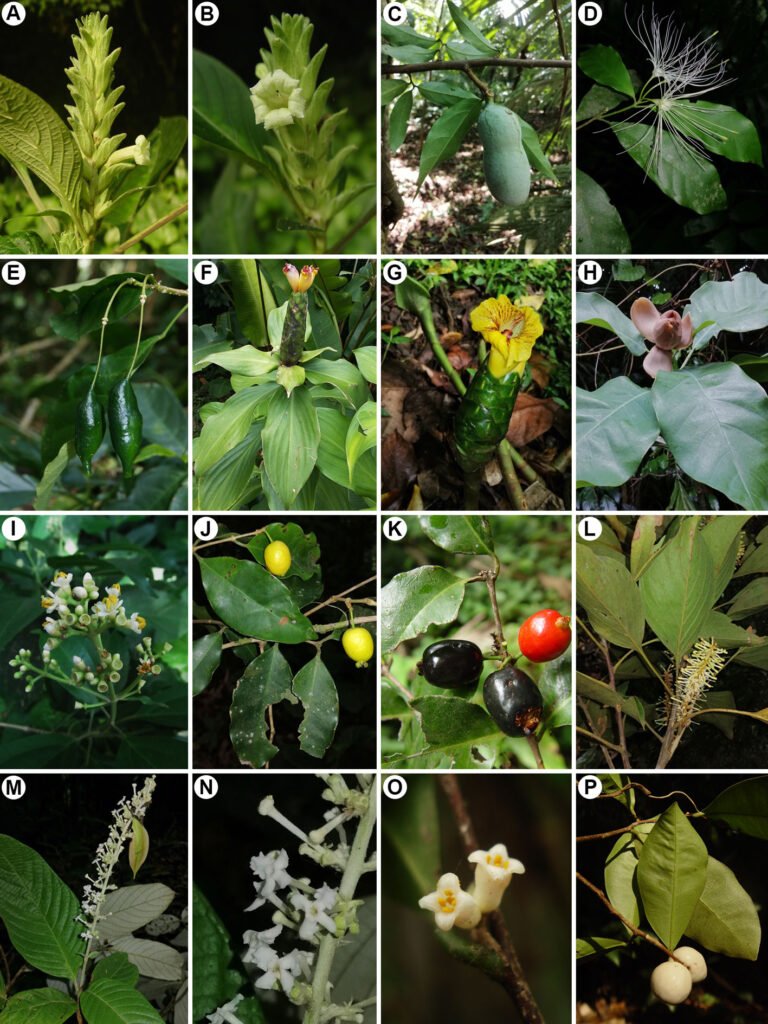

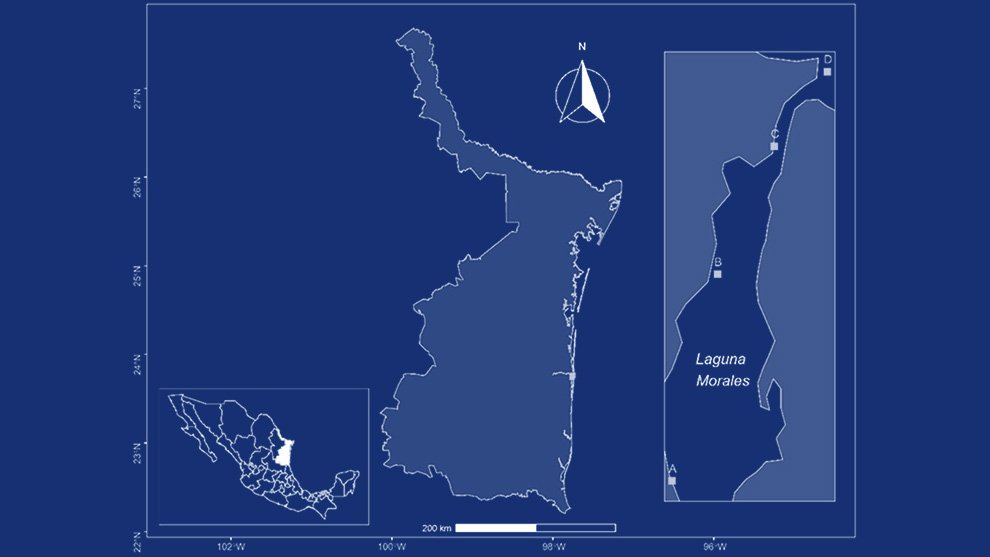

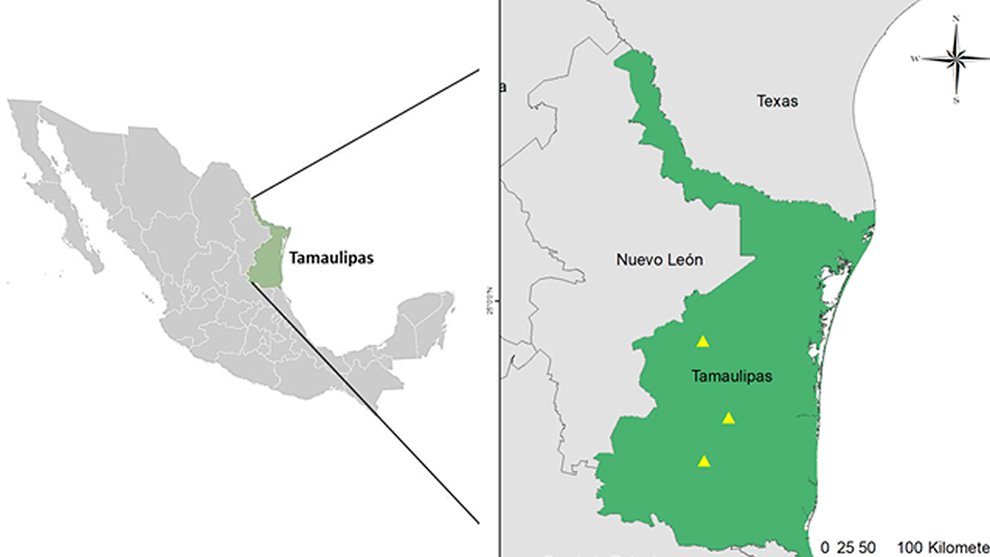

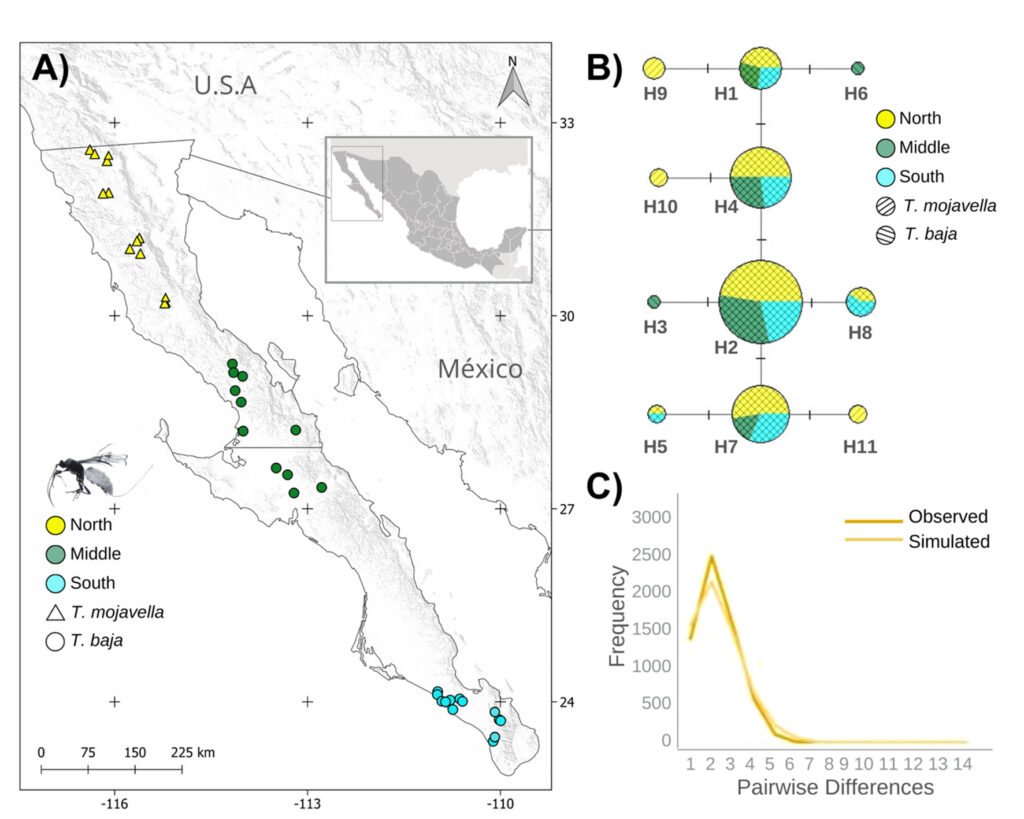

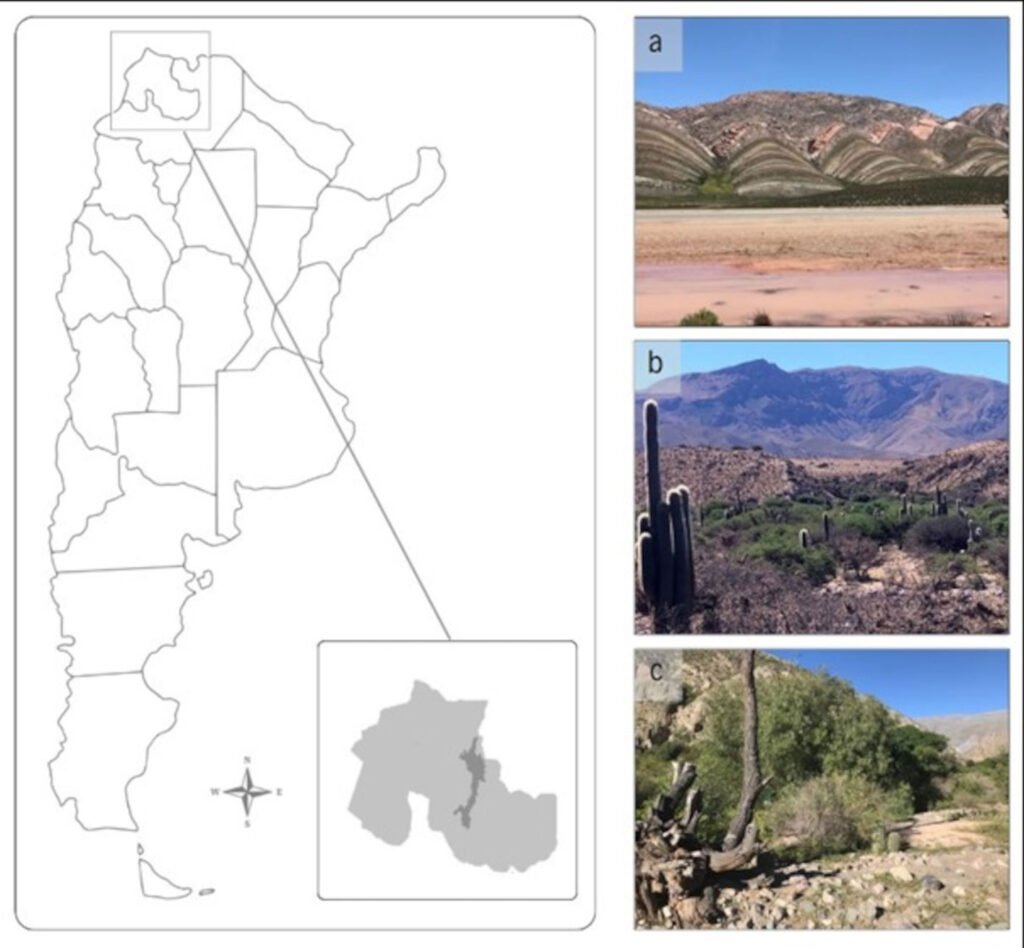

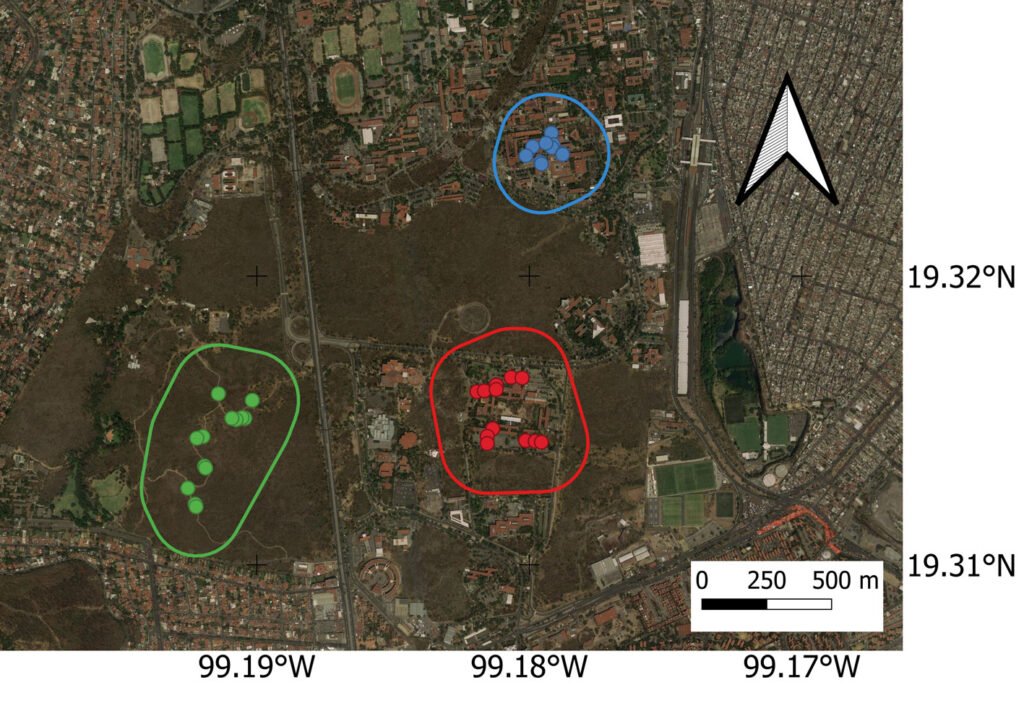

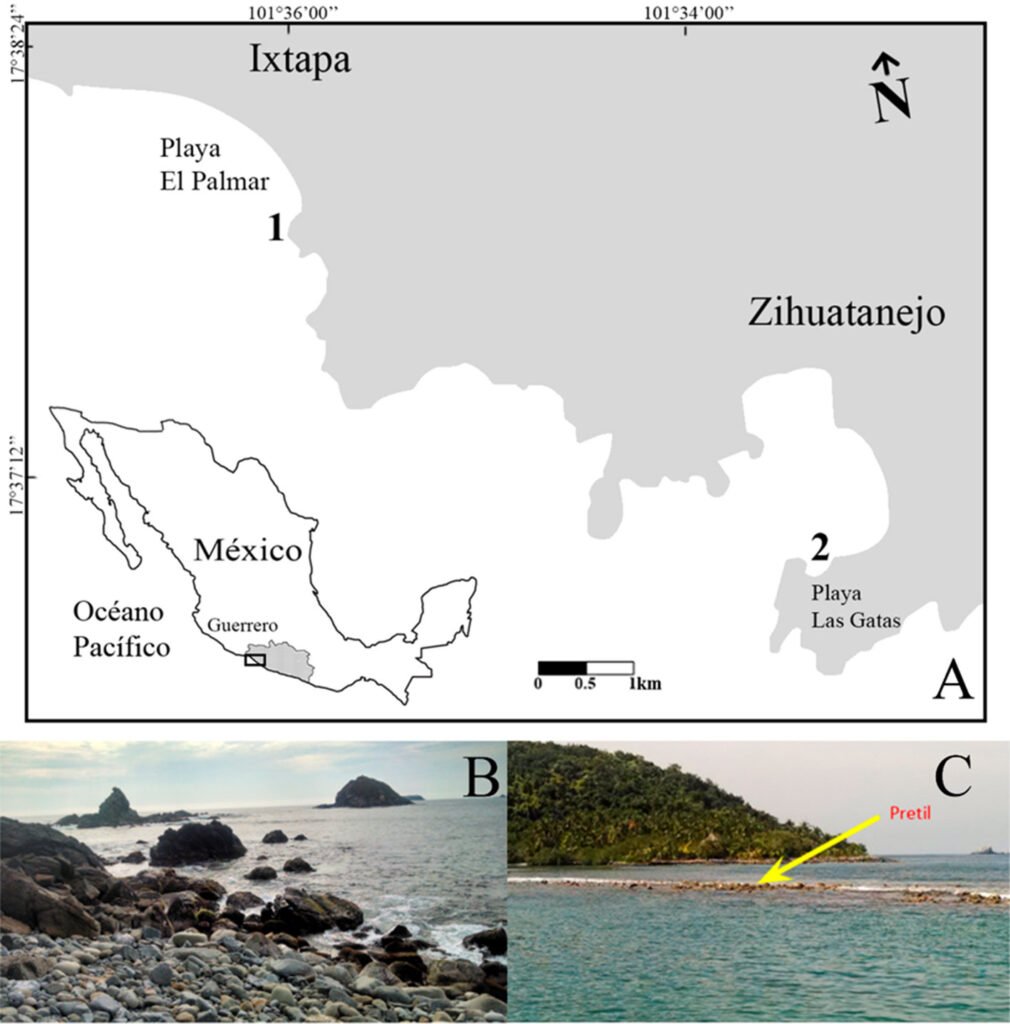

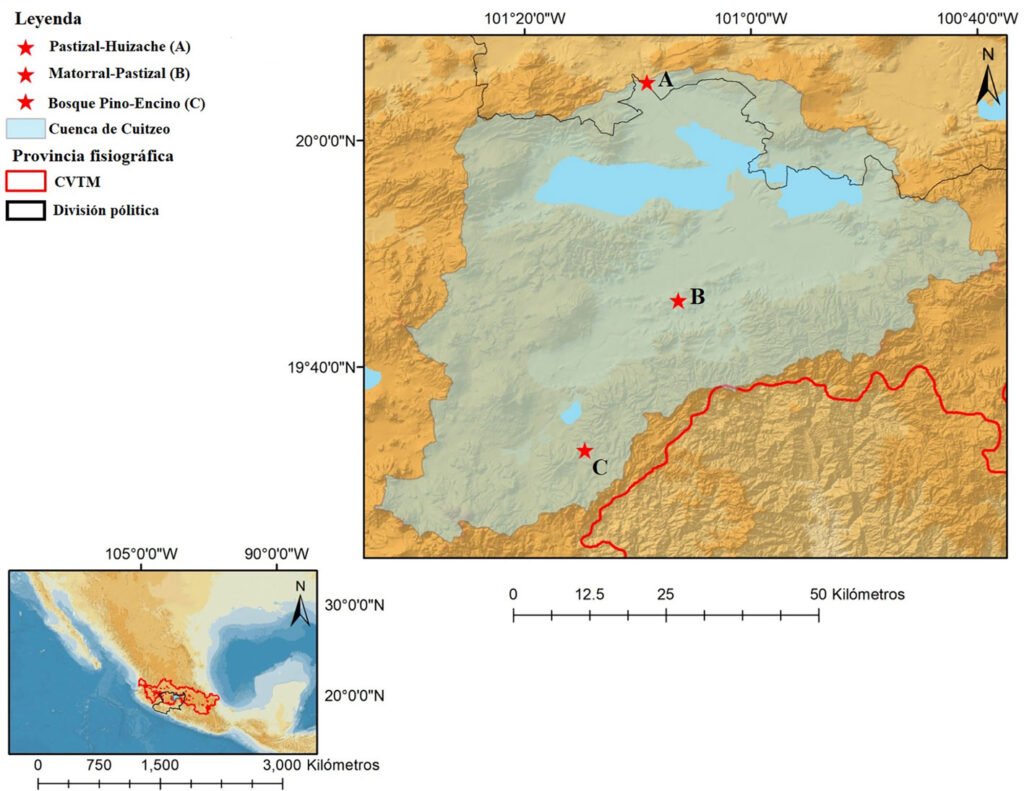

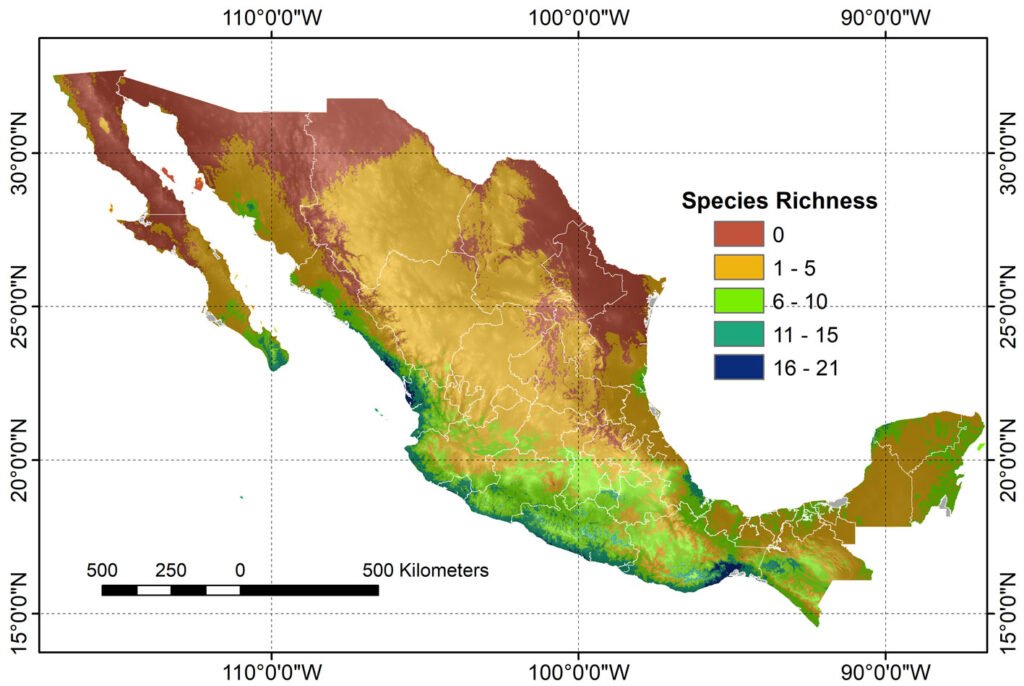

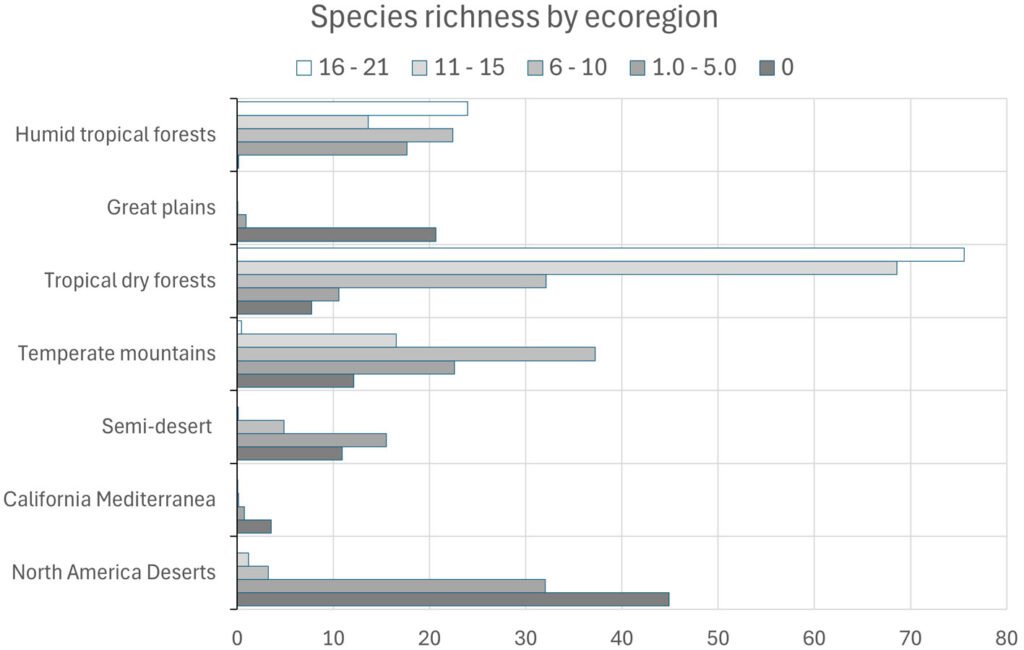

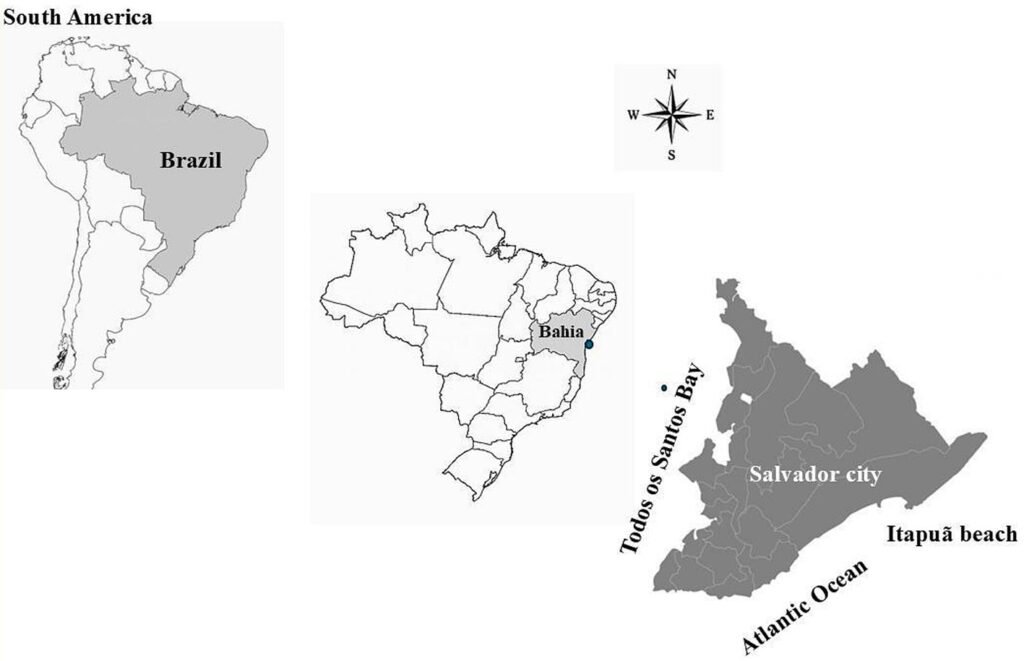

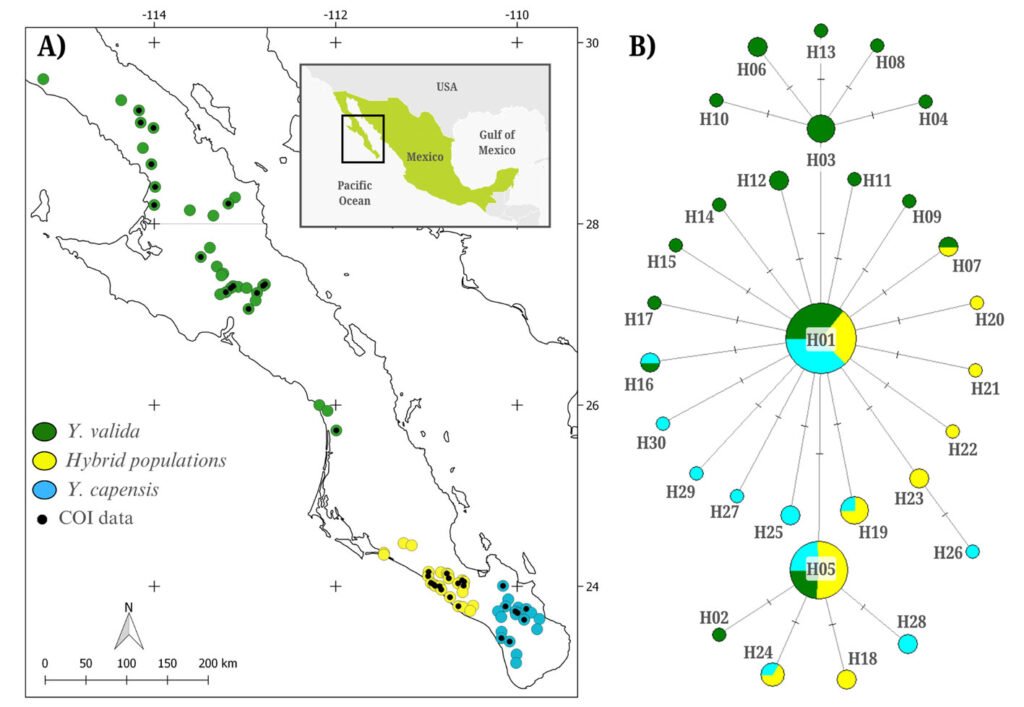

The International Barcode of Life (iBOL) has grown as a powerful tool for discovering biodiversity, among other applications (https://ibol.org). Scorpion barcoding studies have permitted the identification and delimitation of species in several regions of the world (Fet et al., 2014, 2016; Goodman, Prendini, & Esposito, 2021; Podnar et al., 2021). Despite the high diversity of scorpions in Mexico —an update by Ponce-Saavedra et al. (2023) comprises 311 scorpion species— only 1 mini-barcoding study has been conducted (Goodman, Prendini, & Esposito, 2021). Herein, we present a second scorpion barcoding study for this country but aim at discovering the components of a local scorpion assembly. Colima exhibits a complex topology comprising littorals with a tropical climate and extreme topological variation from sea level to mountain ranges rising to over 4,000 m in approximately 5,600 km2. Colima’s territory supports a rich local flora and fauna (Ramírez-Ruiz & Bretón-González, 2016). Colima lies between the limits of the Nearctic and Neotropical biogeographical Realms (Fig. 1B). Beyond its complexity, Colima represents an enclosed littoral surrounded by mountain ranges and 3 large rivers that divide the territory into 2 sections (Fig. 1), which makes it a well-defined and manageable geographical unit ideal for studying a unique community of scorpions. Thus far, 2 families, 3 subfamilies, 5 genera, and 12 species of scorpions have been identified in Colima (Table 1). The knowledge of scorpion diversity and evolutionary studies in Mexico has steadily been unveiling one of the vastest biodiversity hotspots in the world. For instance, 2 of the most diverse scorpion families and subfamilies, Vaejovidae (Syntropinae) and Buthidae (Centruroidinae), have been treated in recent phylogenetic and taxonomic analyses (Esposito & Prendini, 2019; González-Santillán & Prendini, 2013, 2015).

This contribution aims to survey the scorpion richness in Colima, using not only the COI-barcoding genetic marker but 2 additional mitochondrial markers and 1 nuclear marker to establish a framework to build a stable and predictable taxonomy. Taking advantage of robust phylogenies produced for the 2 families distributed in Colima, we use these topologies as a baseline for comparison to test the presence of several previously reported species and to taxonomically circumscribe our fresh samples. Unlike other barcoding studies, our approach seeks to unveil the richness within the state instead of focusing on delimiting the species of a taxonomic group of scorpions.

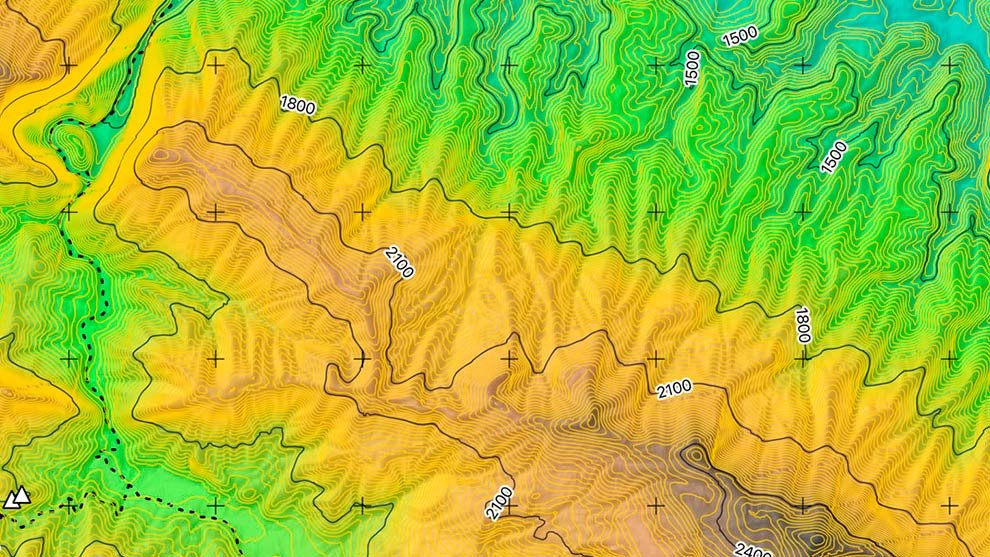

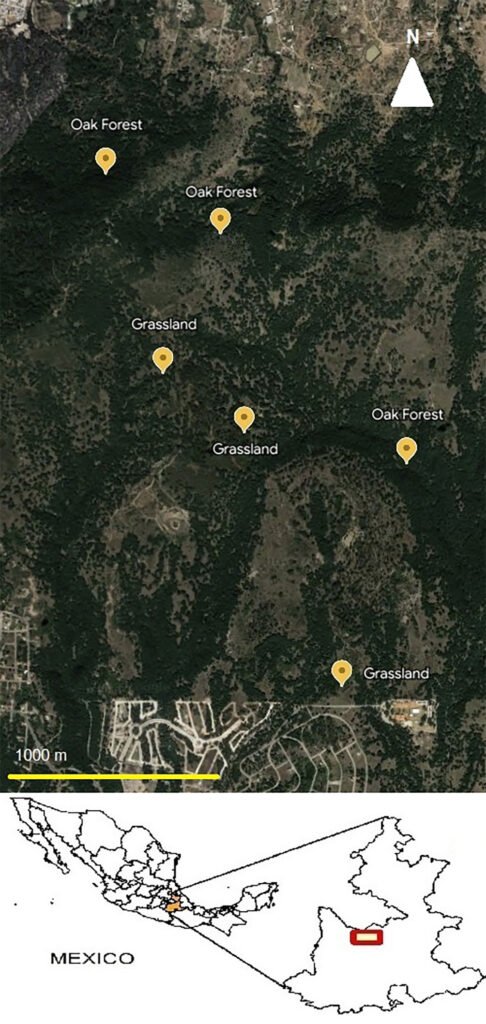

Materials and methods

We conducted field collections during May and September 2015-2018 in various ecosystems, including tropical deciduous forest, oak-pine, and tropical forest within the state of Colima, at elevations ranging from 47 to 2,200 m. (Table 2). Logistically, we leveraged our collection sites with the help of private landowners who gave us access to their property. Specimen collection methods included direct collection during the day by moving objects on the ground or by ultraviolet detection during the night. To preserve specimens, ethyl alcohol at 90% was used and stored at -80 °C. Each specimen lot carried a label with coordinates and locality information. We obtained scorpions from 14 localities and sequenced 18 samples of Centruroides from Colima (Table 2).

Table 1

List of families, subfamilies, genera, and species recorded in the state of Colima. *Species of Centruroides cited by Ponce-Saavedra et al. (2016). The species in bold font were not found in Colima in this study. Numbered species were reported by González-Santillán et al. (2019).

| Families | Subfamilies | Species |

| Buthidae | Centruroidinae | 1. Centruroides elegans (Thorell, 1876)* 2. Centruroides hirsutipalpus Ponce-Saavedra & Francke, 2009* 3. Centruroides infamatus (C.L. Koch, 1844)* Centruroides limpidus (Karsch, 1879)* Centruroides ornatus Pocock, 1902 4. Centruroides tecomanus1 Hoffmann, 1932* 5. Centruroides possanii González-Santillán, Galán-Sánchez & Valdez-Velázquez Centruroides new sp 1 Centruroides new sp 2 Centruroides tecomanus 2 |

| Vaejovidae | Syntropinae | 6. Konetontli ilitchi González-Santillán & Prendini, 2015 7. Thorellius cristimanus (Pocock, 1898) 8. Thorellius intrepidus (Thorell, 1876) 9. Mesomexovis aff. occidentalis |

| 10. Vaejovis janssi Williams, 1980 | ||

| Vaejovinae | 11. Vaejovis monticola Sissom, 1989 12. Vaejovis sp. mexicanus group |

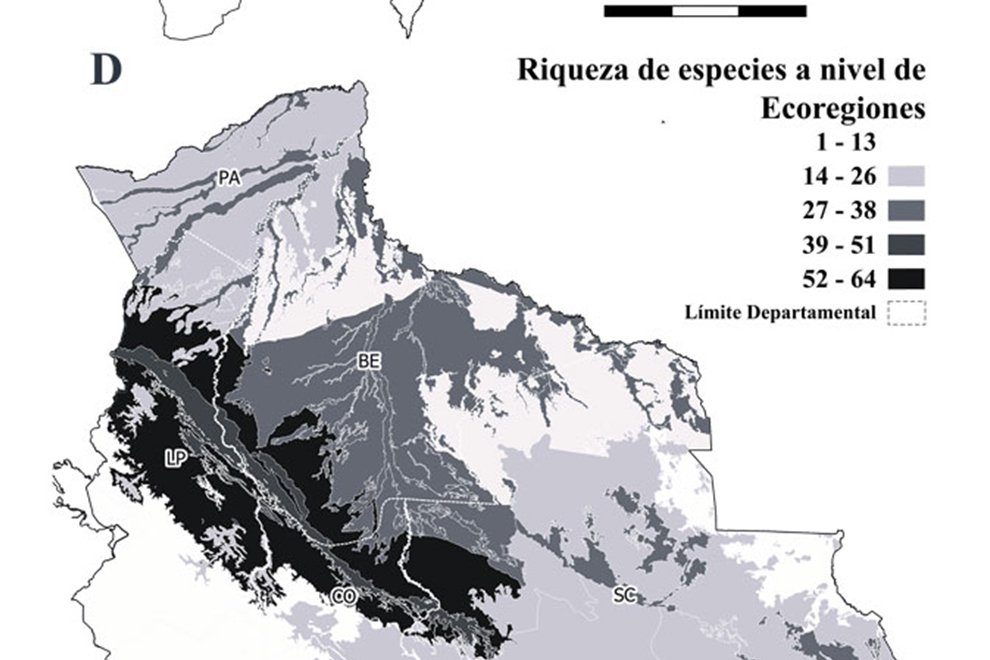

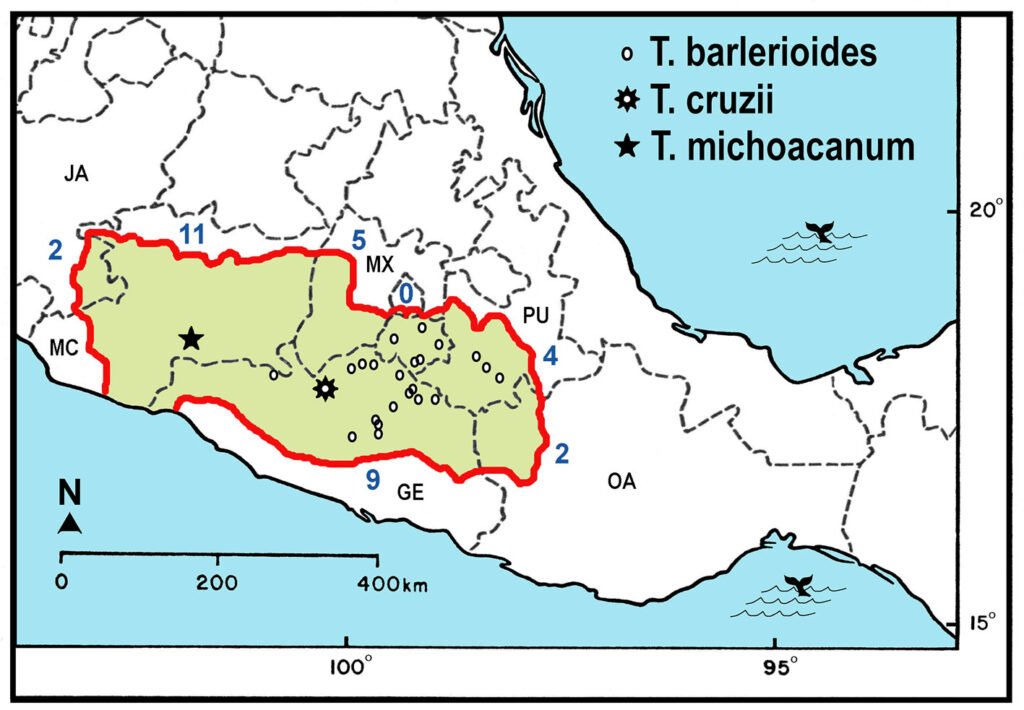

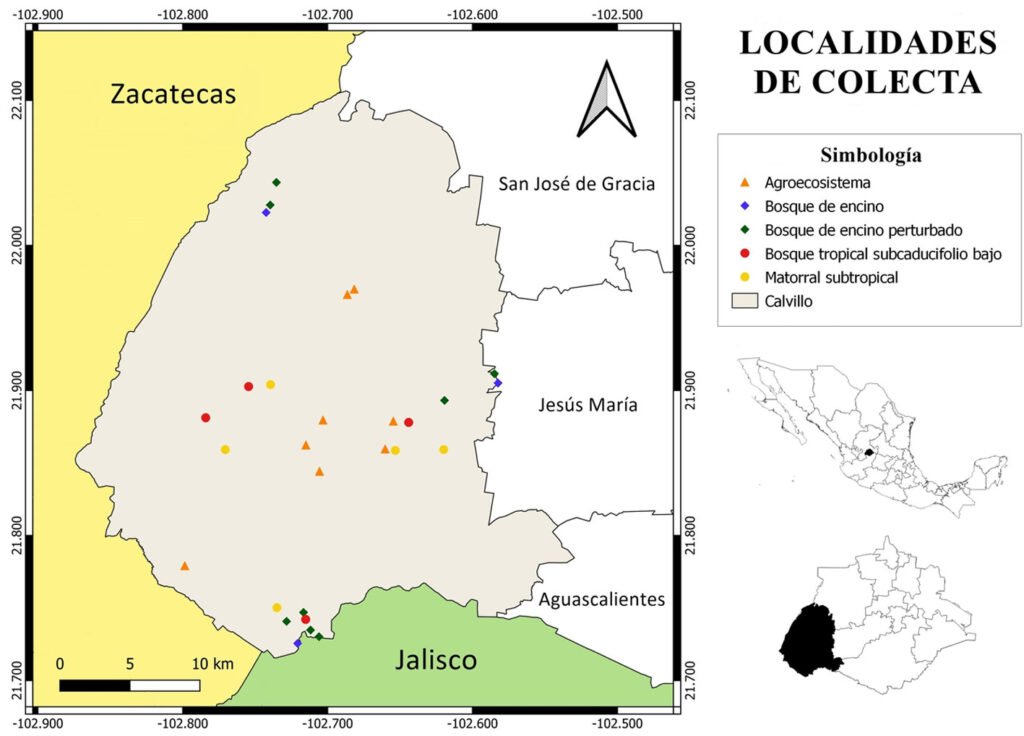

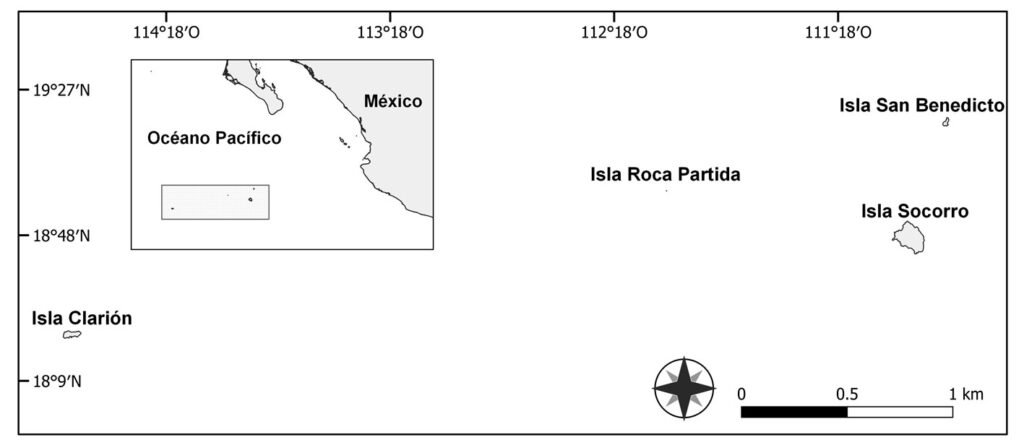

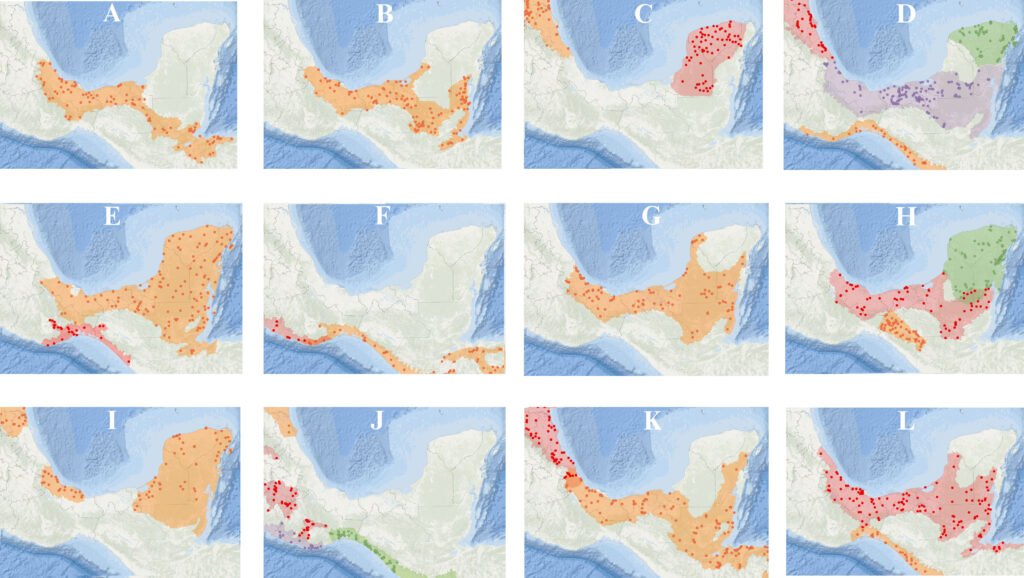

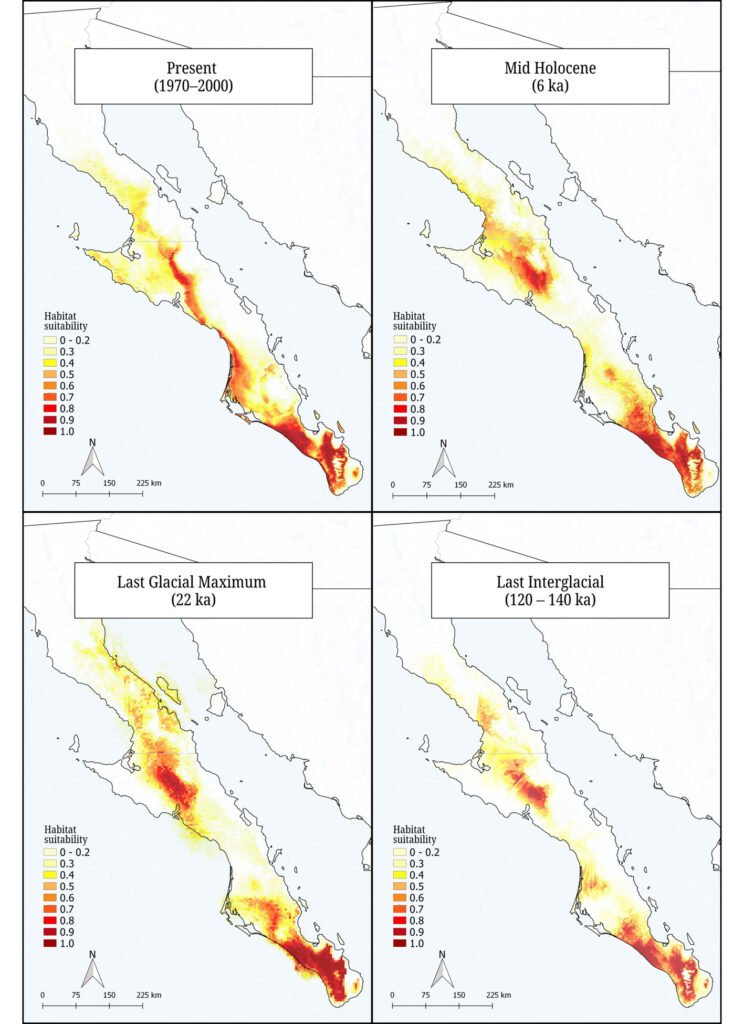

Figure 1. Map of the west coast of Mexico. A, Orographic and hydrographic elements of Colima (COL) and the surrounding states of Jalisco (JAL) and Michoacán (MIC). 1, Manantlán Sierra; 2, massive Cerro Grande; 3, Colima Volcano; 4, Marabasco or Cihuatlán River; 5, Armería River; 6, Coahuayana River. B, Biogeographical provinces (Morrone et al., 2017). Area within the green line corresponds to the Sierra Madre del Sur and north Colima Volcano Trans Mexican Volcanic Belt province (Morrone et al., 2017) —notice that both provinces are connected in Colima. Area outside the green line corresponds to the Pacific Lowlands province (Morrone et al., 2017). Orographic components are indicated in gray scale from light low elevation to dark high elevation.

Table 2

Collection sites of the scorpion species used in this study. The number within parenthesis after the species name is the number of samples processed from this locality and included in the phylogenetic analyses as terminals. Superscript numbers indicate sources of sequences as follows: 1Bolaños et al. (2019), 2Esposito et al. (2018), 3Esposito and Prendini (2019), 4González-Santillán and Prendini (2015). Cells filled in grey color are samples obtained from GenBank.

| Species | Municipality | Locality | Latitude | Longitude | Elevation |

| Thorellius cristimanus (2) | Comala | La Yerbabuena | 19°27′59.55″ | -103°41′46.64′′ | 1,358 m |

| Centruroides ornatus (2) | Comala | Agosto | 19°23′51.74′′ | -103°44′03.08′′ | 1,076 m |

| Thorellius cristimanus | |||||

| *Centruroides tecomanus2 | Colima | Comunidad La Capacha | 19°04′58.40′′ | -103°41′24.67′′ | 656 m |

| *Centruroides tecomanus2 | Colima | Tepames | 19°06′22.8′′ | -103°59′11.07′′ | 450 m |

| Thorellius intrepidus (3) | Coquimatlán | El Palapo | 19°11′54.6′′ | -103°54′50′′ | 275 m |

| *Centruroides tecomanus2 | Cuauhtémoc | Camino a Altozano | 19°18′30.19′′ | -103°40′23.83′′ | 789 m |

| Thorellius cristimanus | |||||

| *Centruroides tecomanus1(2) | Cuauhtémoc | Ocotillo | 19°20′00.00′′ | -103°39′02.00′′ | 895 m |

| *Centruroides tecomanus2 | Ixtlahuacán | San Gabriel | 18°54′24.48′′ | -103°44′05.61′′ | 462 m |

| Mesomexovis aff. occidentalis | |||||

| Centruroides hirsutipalpus | Minatitlán | Minatitlán | 19°23′01.73′′ | -104°03′35.19′′ | 703 m |

| Centruroides possanii (2) | Minatitlán | Terrero | 19°26′35.94′′ | -103°57′05.67′′ | 2,200 m |

| Centruroides possanii (2) | Minatitlán | Mirador el Filete | 19°26′40′′ | -103°58′10′′ | 2,137 m |

| Vaejovis sp. (mexicanus group) | |||||

| Centruroides sp. 2 (2) | Manzanillo | La central | 19°08′38.14′′ | -104°26′04.10′′ | 47 m |

| *Centruroides tecomanus1 | |||||

| *Centruroides tecomanus2 | |||||

| Centruroides sp. 1 | Tecomán | Chanchopa | 18°51′58.55′′ | -103°44′10.10′′ | 41 m |

| Thorellius intrepidus (2) | Villa de Álvarez | Rancho Blanco | 19°14′24.71′′ | -103°45′49.45′′ | 455 m |

| Thorellius intrepidus4 | La Huerta (Jal.) | Estación de Biología Chamela | 19°30′14.15′′ | -105°2′16.50′′ | 33 m |

| Centruroides elegans (2) | |||||

| Centruroides suffusus | Durango (Dgo.) | El Salto, 50 km E Durango | 23°45′51.41′′ | -105°19′49.16′′ | 2,847 m |

| Centruroides limpidus | Iguala (Gro.) | Iguala | 18°20′11.87′′ | -99°29′29.65′′ | 823 m |

| Centruroides sculpturatus | Cumpas (Son.) | 18 km NE de Nacozari | 30°16.473′ | -109°50.070′ | 930 m |

| Centruroides noxius | Pantanal (Nay.) | Pantanal | 21°25′24.42′′ | -104°50′47.89′′ | 921 m |

| Centruroides huichol | Nayarit | – | – | – | – |

| Centruroides infamatus115scrp | Guanajuato (Gto.) | Guanajuato | – | – | – |

| Centruroides ornatus2LP1822 | Tandamangapio (Mich.) | Los Tabanos | 19.9749° | – 102.84226° | 223 m |

| Centruroides ornatus3 2003 | Michoacán | – | – | – | – |

| *Centruroides tecomanus11 25scrp | Comala (Col.) | – | – | – | – |

| *Centruroides tecomanus12 2007 | Michoacán | – | – | – | – |

| Mesomexovis occidentalis4 LP 7056 | Acapulco (Gro.) | Cumbres de Llano Largo | 16°49.505 | -99°49.9990 | 317 m |

| Table 2. Continued | |||||

| Species | Municipality | Locality | Latitude | Longitude | Elevation |

| Mesomexovis spadix4LP6373 | León (Gto.) | San Antonio de Padua | 20°34.5170 | -100°57.217 | – |

| Mesomexovis subcristatus4LP 2049 | Tehuacán (Pue.) | Tehuacán, 2 km east | 18°24.0020 | -97°22.8670 | 1435 m |

| Thorellius cristimanus4LP 5325 | Álvaro Obregón (Mich.) | Álvaro Obregón | 19°02.3100 | -102°58.405 | 462 m |

| Thorellius cristimanus4LP 6551 | Coquimatlán (Col.) | Road to Coquimatlán, km 71 | 19°06.7750 | -103°51.1850 | 336 m |

| Thorellius intrepidus4LP 6377 | Comala (Col.) | Comala | 19°19.000 | -103°45.0000 | – |

| Thorellius intrepidus4LP 6379 | Colima (Col.) | Los Ortices | 19°06.0468 | -103°44.0226 | 343 m |

| Vaejovis carolinianus4LP 1576 | South Carolina | – | – | – | – |

| Vaejovis pequeno4LP 6308 | Soyopa (Son.) | Sierra El Encinal, 9 km from crossroad on Highway Mex 16 to El Encinal | 28°35.4120 | -109°27.1480 | 380 m |

| Vaejovis rossmani4LP 2027 | Hidalgo (Tams.) | Conrado Castillo | 23°56.01735 | -99°28.04817 | – |

*Genetically differentiated species.

We also included 8 species from outside the state to test the presence of C. elegans, C. infamatus, and C. limpidus reported previously in the literature (Ponce-Saavedra et al., 2016); C. noxius and C. suffusus for comparative purposes and samples of C. tecomanus and C. ornatus from GenBank with a total of 31 specimens of the genus Centruroides within 4 species groups. Unlike buthids, we obtained 12 samples of vaejovids to include in this analysis. To evaluate the identity of vaejovids, we used the BLAST® suite (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) to search for similar sequences deposited in the nucleotide collection database at NCBI. Thorellius has been revised recently (González-Santillán & Prendini, 2018). Therefore, several DNA sequences are available, and fewer sequences of Mesomexovis sp. and Vaejovis sp. were available in GenBank, as they are still unrevised. Using the genetic markers as queries, we obtained 10 additional samples. The total number of taxonomic specimens used for these analyses was 53 (Tables 2, 4).

Genomic DNA was extracted from the legs or pedipalp of specimens using Qiagen Dneasy/trisol method Tissue Kits or a DNAzol Genomic DNA isolation Reagent kit (Molecular Research Center INC, Cincinnati, Oh). We amplified 3 mitochondrial markers, 12S rDNA, 16S rDNA, and the barcode COI, and the nuclear marker 28S rDNA. We performed the Polymerase Chain Reaction with the following thermal profile: an initial denaturation step (3 min at 94°C) followed by 35 cycles including denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing (46-55°C) for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 30 s, with a final extension step at 72°C for 7 min. The PCR reaction was conducted using PureTaq-Ready-To-Go PCR Beads (GE Healthcare), 2 µl of DNA template, 21 µl of DNA grade H2O, and 1 µl of each direction primer listed in Table 3. We verified PCR products with a 1% agarose-TBE electrophoresis gel stained with CYBR Safe. For purification of the amplified products, we used Ampure Magnetic Beads (Beckman-Coulter) and re-suspended in 40 µl DNA grade water by using a Beckman Coulter Biomek NX 18 robot. Each 8 µl cycle-sequenced reaction mixture included 1 µl of Big Dye, 1 µl of Big Dye Terminating buffer, 1 µl of 3.2 pm primer, and 5 µl of gene amplification product. Cycle-sequenced products were purified with CleanSeq magnetic beads on a Biomex NX robot. Products were re-suspended in EDTA, and 33 µl were processed in an Applied Biosystems, Inc. Prism 3730xl automated DNA sequencer. These products were sequenced with the same primer pairs used for amplification at the Laboratorio de Secuenciación Genómica de la Biodiversidad, at Instituto de Biología and Unidad de Síntesis y Secuenciación de DNA, Instituto de Biotecnología, UNAM. The sequences were edited using Sequencher® version 5.4.6.

Table 3

List of primers used to amplify molecular markers.

| Name | Sequence | Reference |

| 12S rDNA | ||

| 12SAI | AAACTAGGATTAGATACCCTATTAT | Kocher et al. (1989) |

| 12SBI | AAGAGCGACGGGCGATGTGT | Kocher et al. (1989) |

| 16S rDNA | ||

| 16SA | CGCCTGTTTATCAAAAACAT | Simon et al. (1994) |

| 16SB | CTCCGGTTTGAACTCAGATCA | Simon et al. (1994) |

| COI | ||

| HCO | TAAACTTCAGGGTGACCAAAAAATCA | Folmer et al. (1994) |

| LCO1 | GGTCAACAAATCATAAAGATATTGG | Folmer et al. (1994) |

| 28S rDNA | ||

| 28SA | GACCCGTCTTGAAGCACG | Nunn et al. (1996) |

| 28SBout | CCCACAGCGCCAGTTCTGCTTACC | Prendini et al. (2005) |

Each genetic fragment was aligned separately for all terminals with MAFFT using the online server (https://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/server/). Since the number of nucleotides per gene was similar, we used the G-ins-i iterative refinement method, as recommended elsewhere (Katoh et al., 2019; Kuraku et al., 2013), and other parameters were kept default. To select the best fit of the substitution model per partition and conduct the phylogenetic analyses, we used IQ-TREE version 2 (Kalyaanamoorthy et al., 2017; Nguyen et al., 2015) and we estimated branch support with 1,000 replicates of the ultrafast bootstrap (UFBOOT) algorithm (Hoang et al., 2018). Furthermore, each genetic marker was analyzed individually to explore its phylogenetic signal and contribution to the final topology. We conducted concatenated and partitioned analyses, handling all matrices in Mesquite (Maddison & Maddison, 2023). For the COI partition we explored the best codon partition per site, but the results had no effect on the topology. Additionally, to evaluate each marker and nucleotide site within each marker, we calculated the gene (GCF) and site (SCF) concordance factors on the topology that we emphasized in the discussion (Mihn et al., 2020).

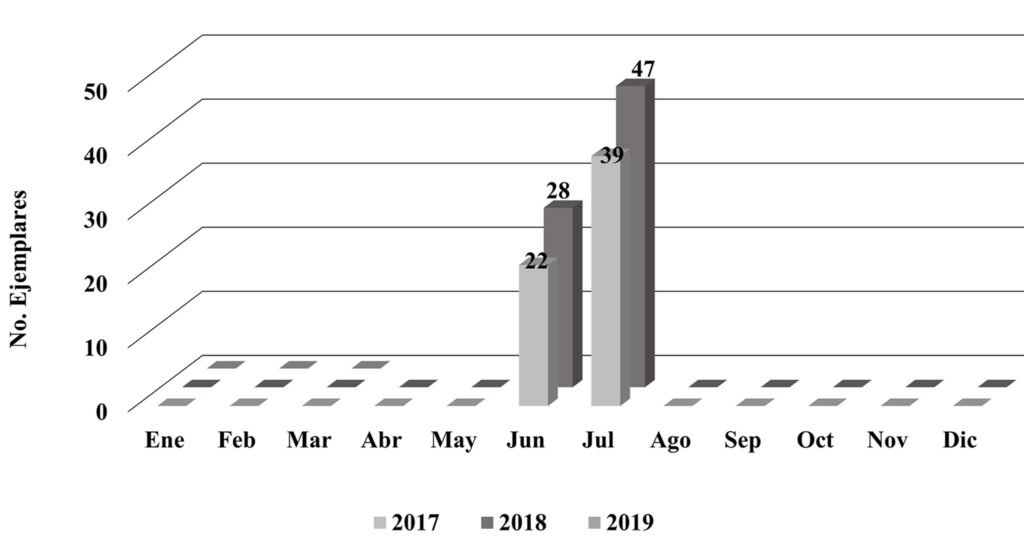

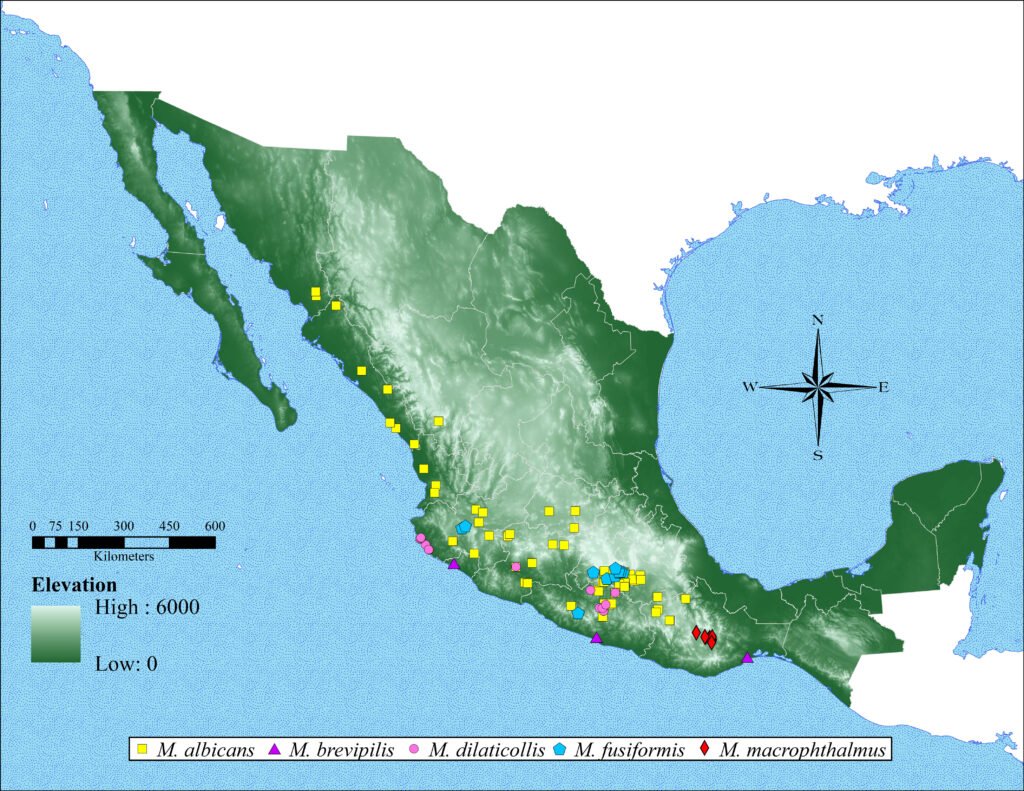

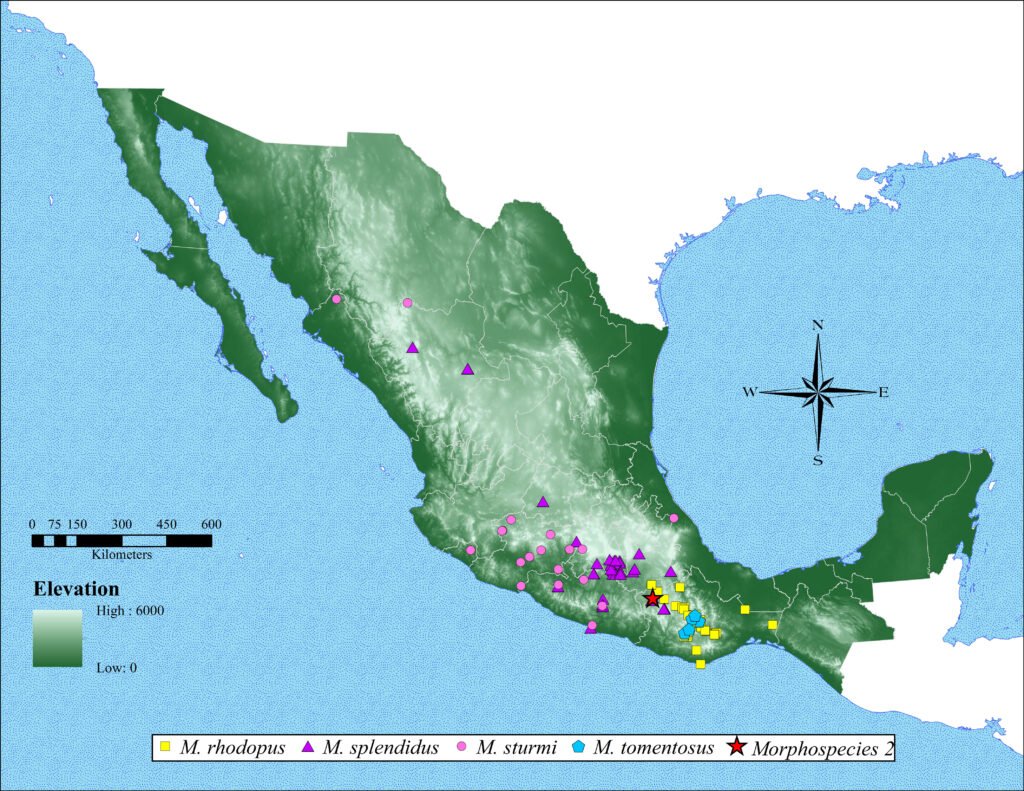

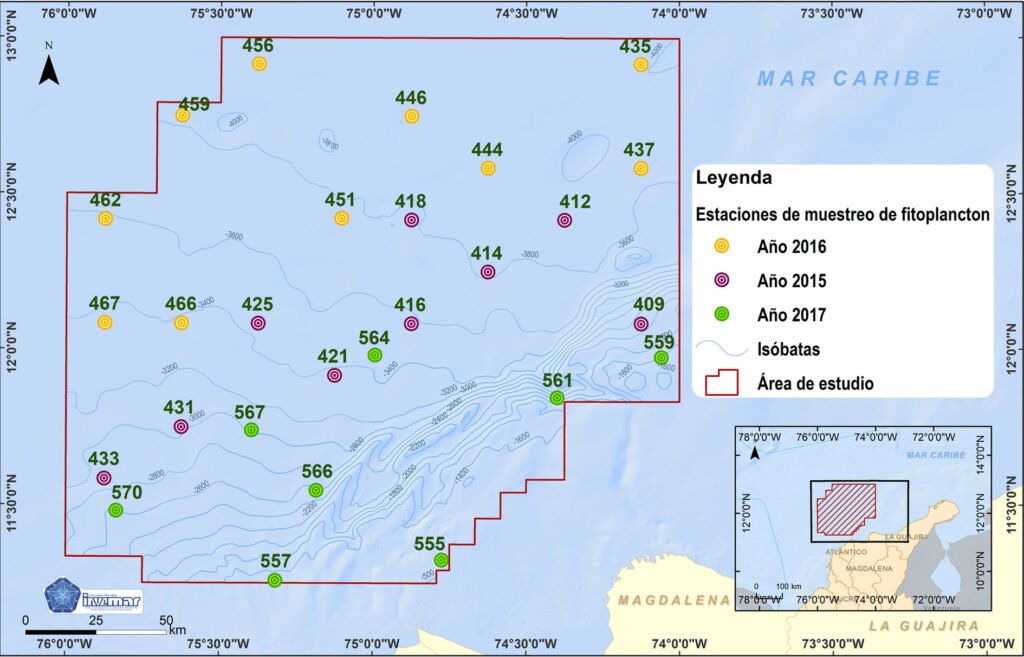

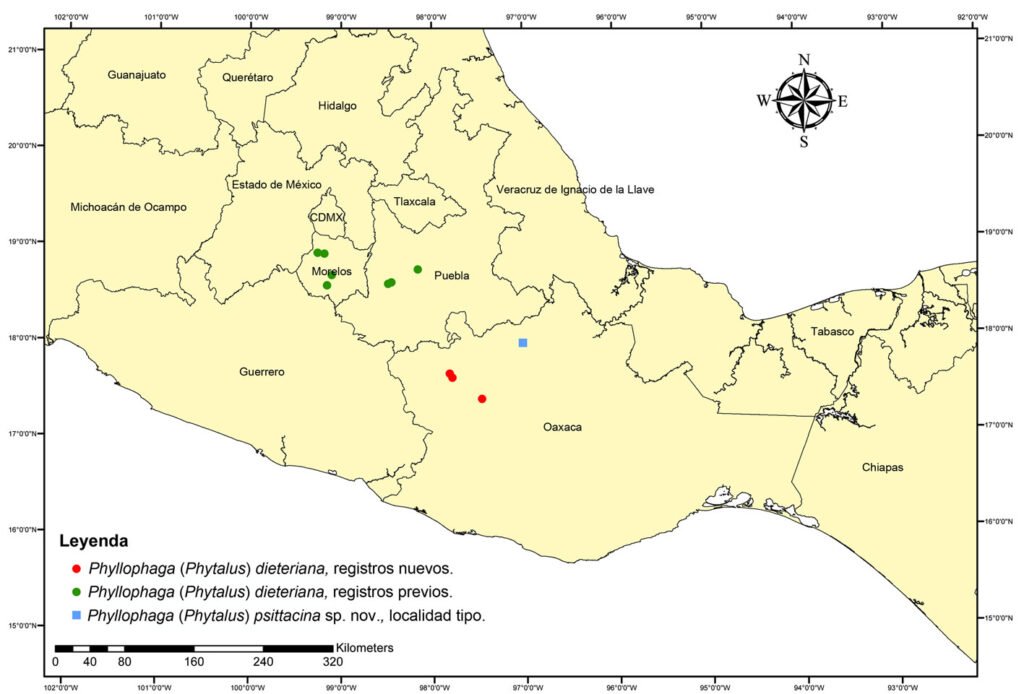

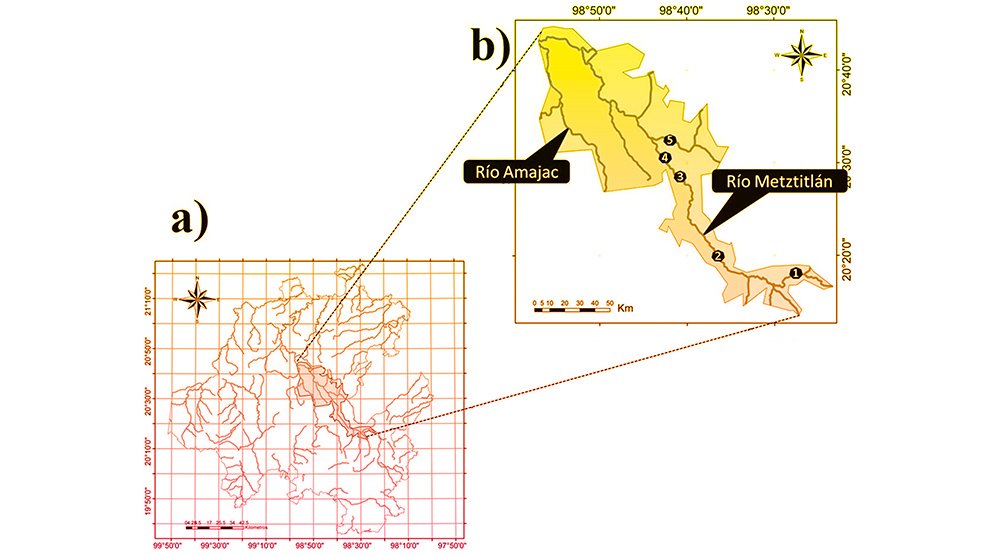

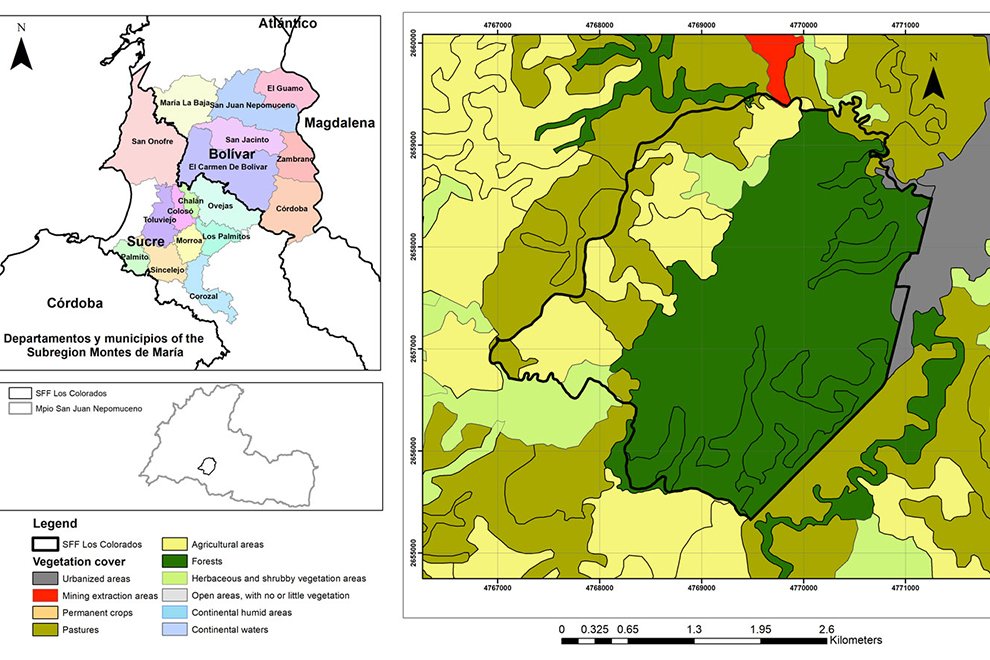

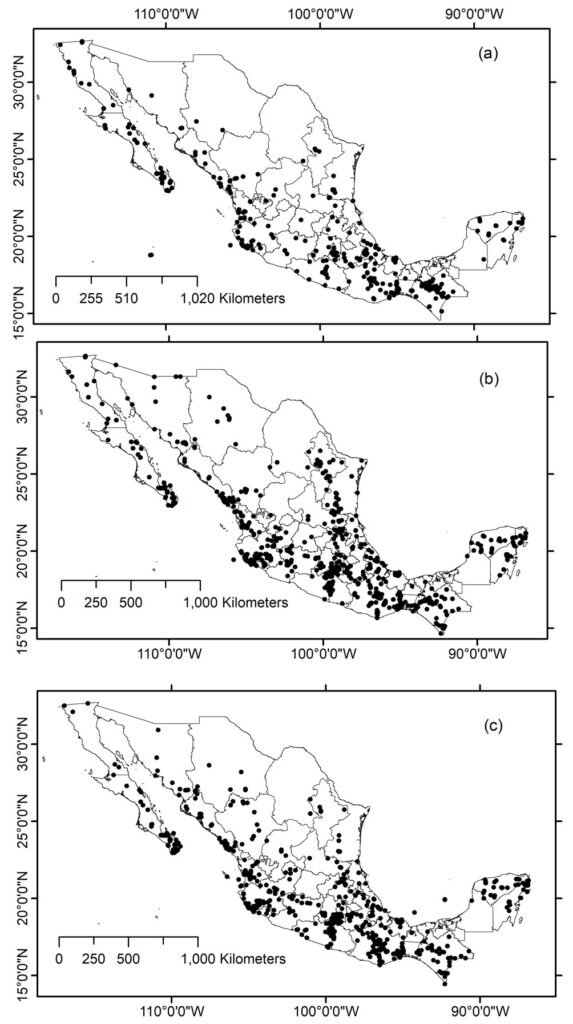

Distributional records and maps. We obtained records with geographical coordinates of the scorpion species treated here via the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) from the InDRE, responsible in Mexico for epidemiological vigilance (Huerta-Jiménez, 2018), and the records published by Ponce-Saavedra et al. (2015). These records were the basis for the species distribution maps depicted in figures 3 to 6. We used the program QGIS 3.16.6-Hannove (QGIS, 2021) to create the distributional maps. The topological model with the data was from Jarvis et al. (2008), and to draw the political boundaries we used shapefiles obtained from Conabio. The biogeographic regionalization of Mexico into provinces and districts follows Morrone et al. (2017) and Morrone (2019).

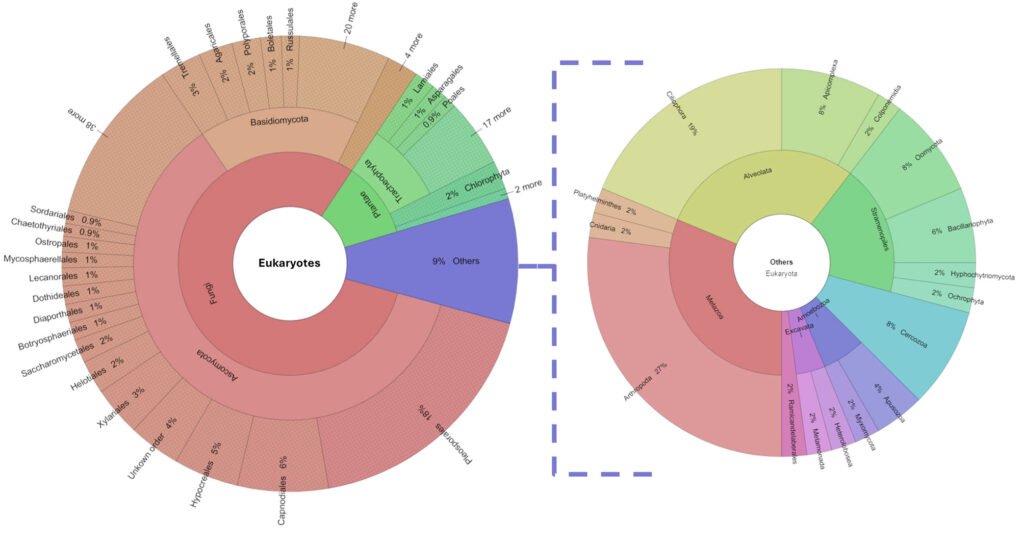

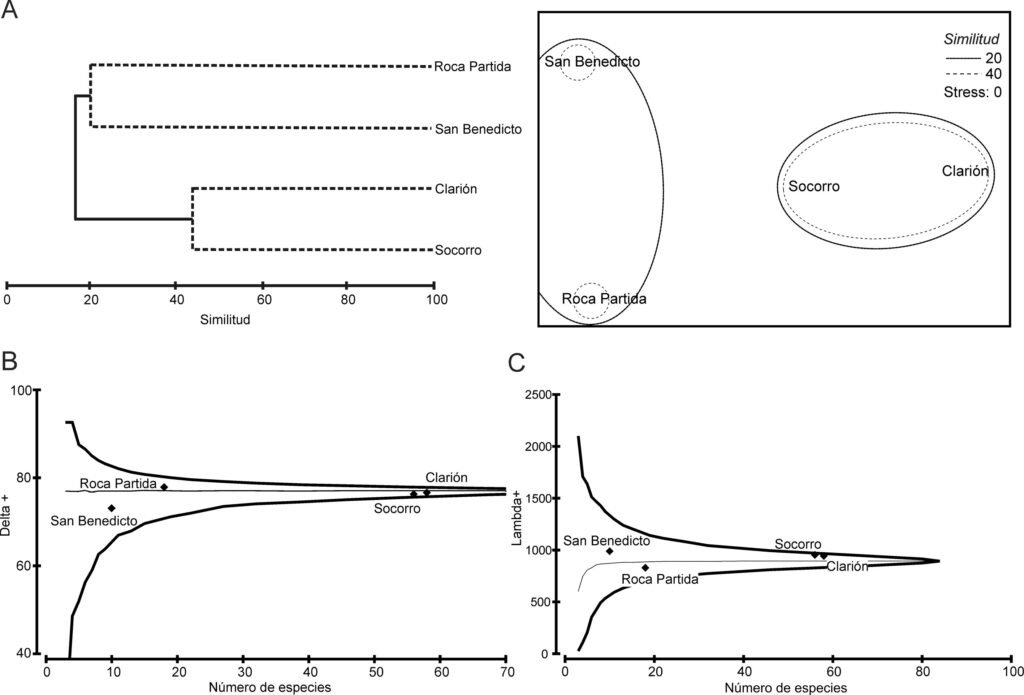

Results

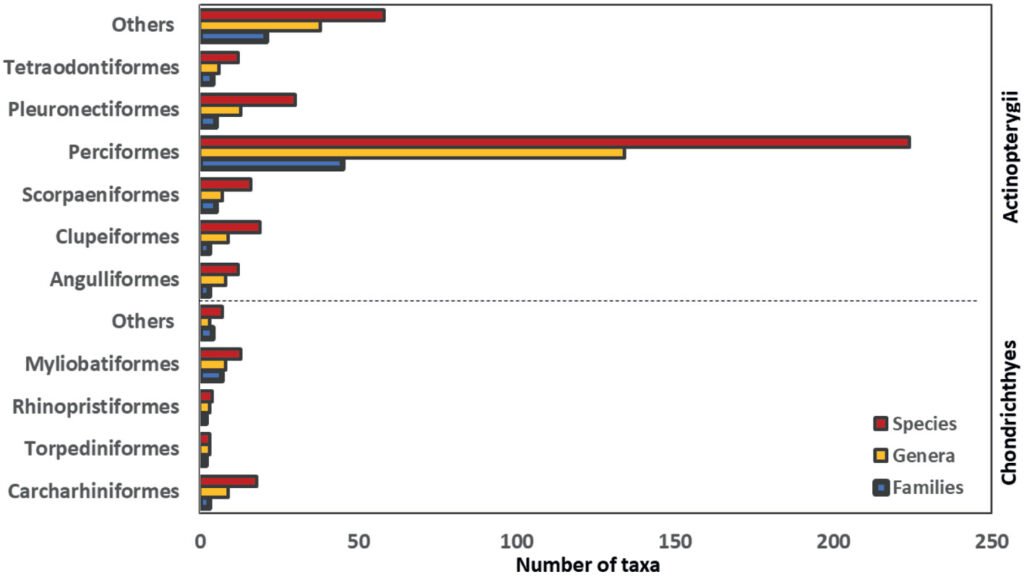

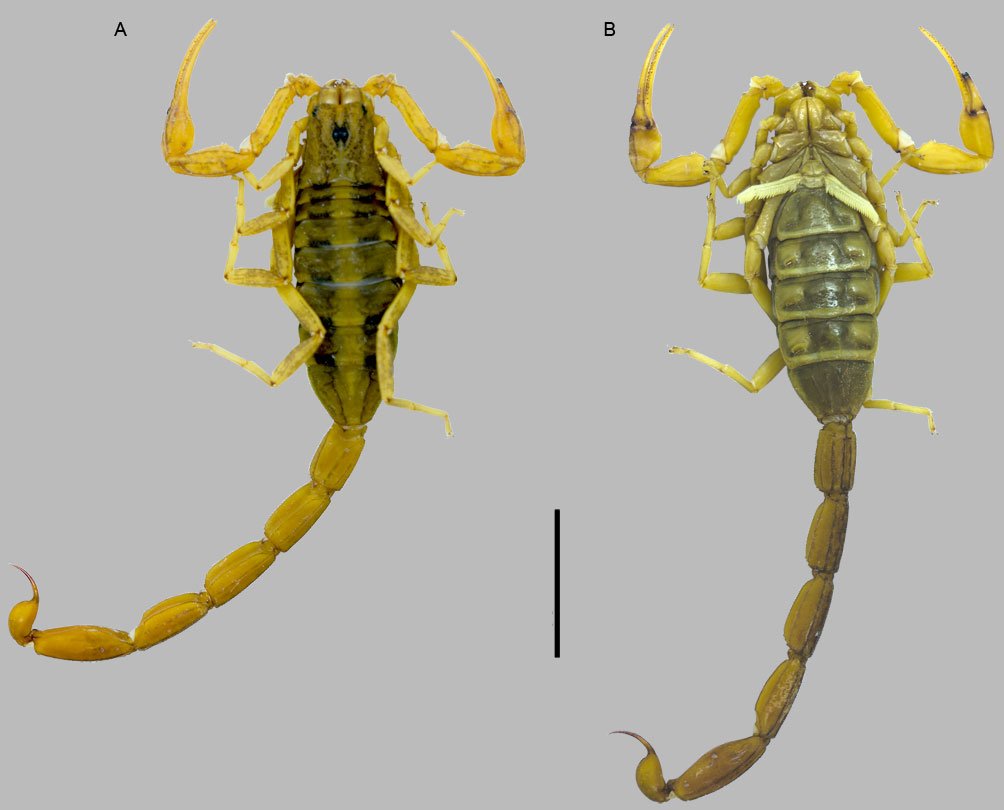

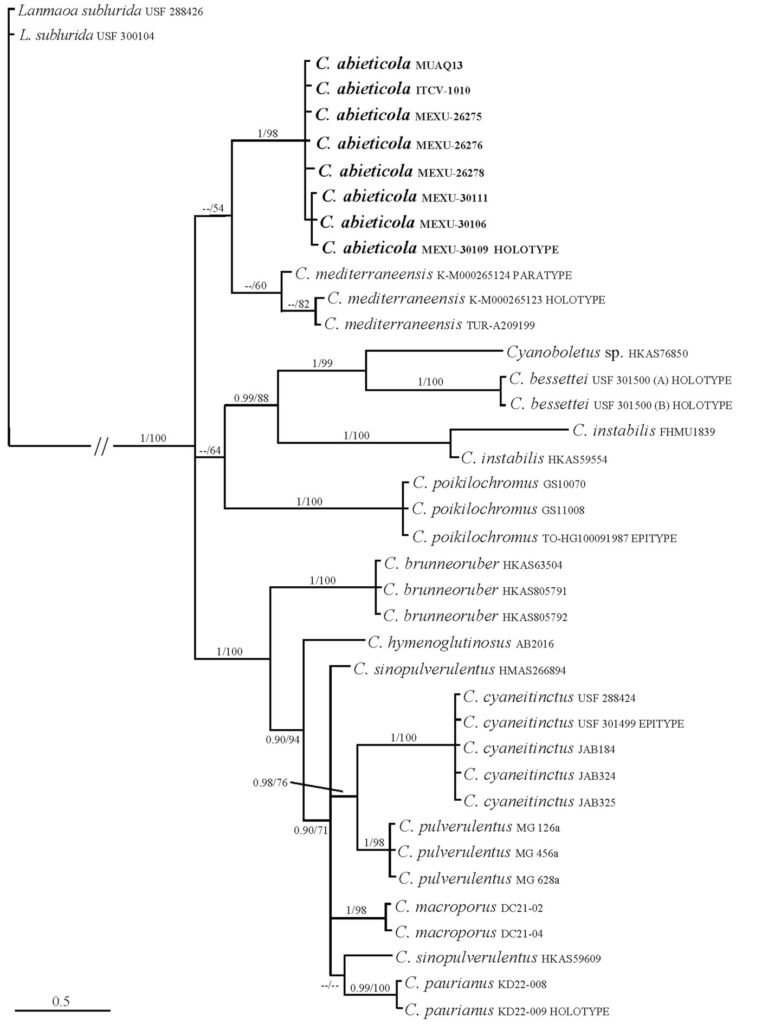

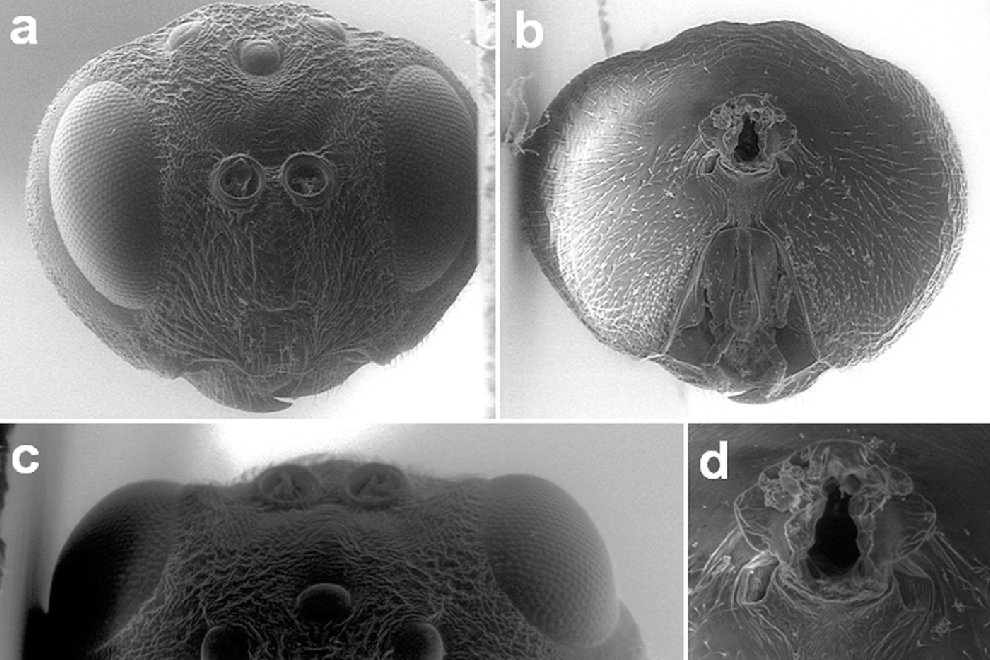

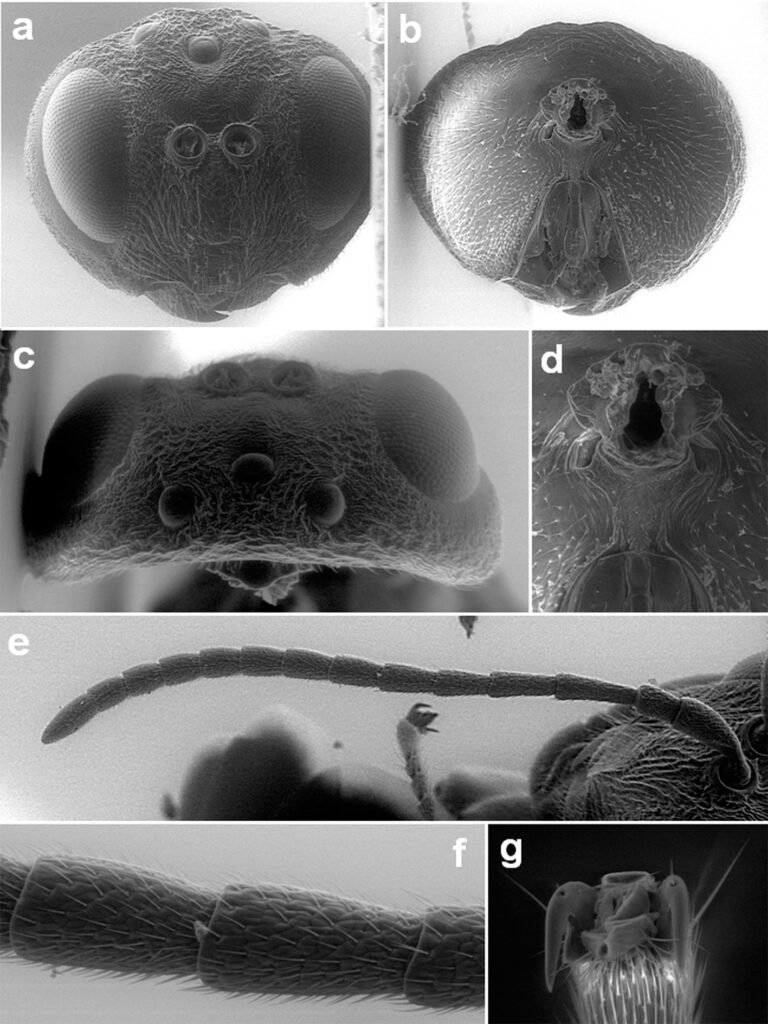

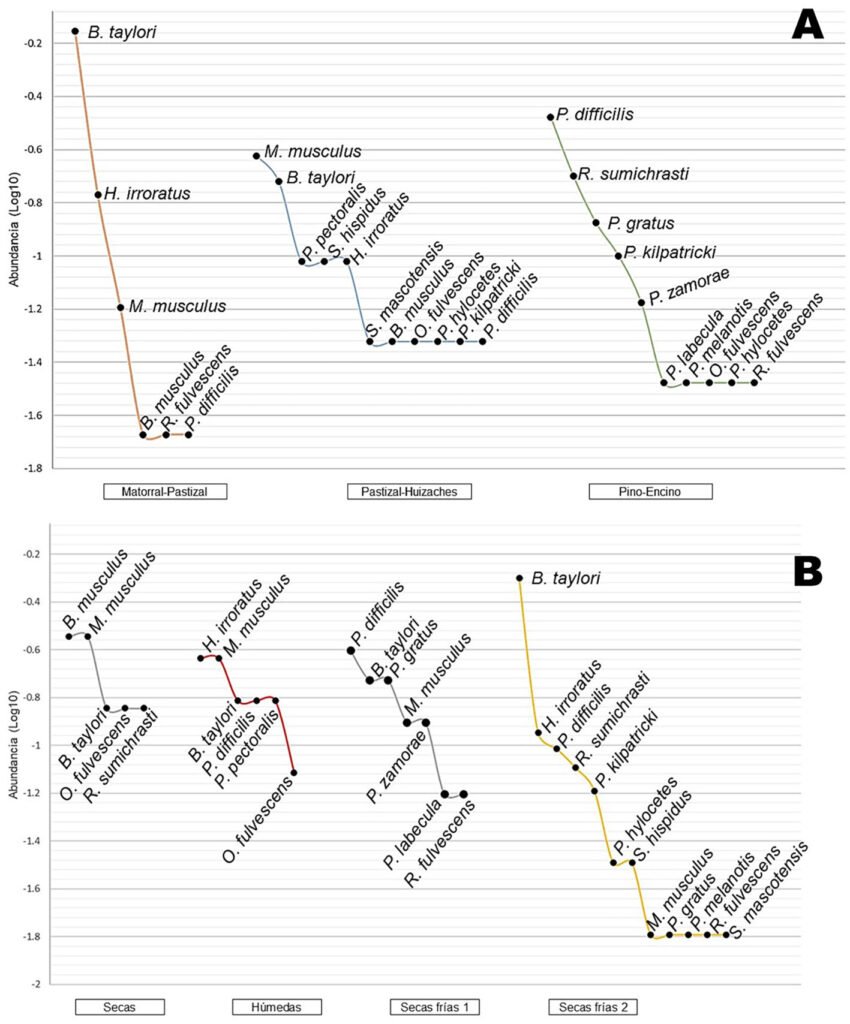

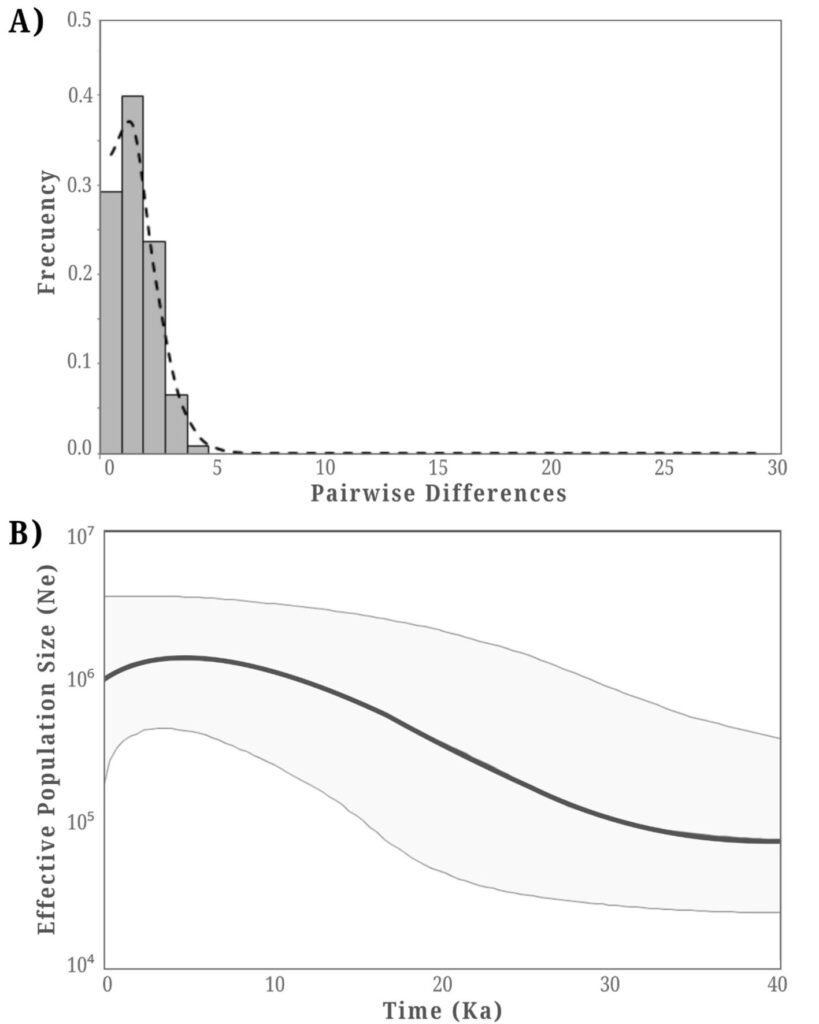

The gene fragments that we obtained are listed in Table 4 and the main statistics of the alignment and concatenated matrix are in Table 5. Our topology produced a clade representing members of the family Buthidae and another clade representing Vaejovidae (Fig. 2). Within buthids, the first clade included C. huichol and C. noxius, component species of the bertholdii species group (Ponce-Saavedra & Francke, 2019), supported by 95% UFBOOT, 100% GCF, and 40% SCF. The next clade included C. elegans, C. limpidus, and a putative undescribed species with lower support values of 68%, 100%, and 38%, respectively, including members of the elegans group. Although with low support, the bulk of species appeared in the third clade comprising species within the infamatus group, with C. tecomanus, C. infamatus, C. possanii, C. hirsuticauda, C. ornatus, and 2 putative new species. The last clade included C. suffusus and C. sculpturatus, whichPonce-Saavedra and Francke (2019) circumscribed within the infamatus and the elegans species group, respectively (Fig. 2). However, the overall topology retrieved herein is concordant with the North American clade of the genus Centruroides (Esposito & Prendini, 2019).

Table 4

Mitochondrial genetic markers 16S, COI, and 12S and nuclear 28S information for samples analyzed in the study. Dash (-) symbols indicate unavailable sequences.

| Species | NCBI:txid | 16S | 12S | COI | 28S |

| Centruroides elegans | 217897 | Cele_30_16S (PP295377) | Cele_30_12S (PP295301) | Cele_30_COI (PP356615) | Cele_30_28S (PP295328) |

| Cele_31_16S (PP295378) | Cele_31_12S (PP295302) | Cele_31_COI (PP355194) | Cele_31_28S (PP295329) | ||

| Table 4. Continued | |||||

| Species | NCBI:txid | 16S | 12S | COI | 28S |

| Centruroides hirsutipalpus | – | Chir_06_16S (PP295353) | Chir_06_12S (PP295277) | Chir_06_COI (PP356614) | Chir_06_28S (PP295310) |

| Centruroides huichol | 2911785 | Chui_38_16S (PP295385) | Chui_38_12S (PP295309) | Chui_38_COI (PP356613) | Chui_38_28S (PP295335) |

| Centruroides infamatus | 42200 | MF134694 | – | MF134798 | MF134763 |

| Centruroides limpidus | 29941 | Clim_34_16S (PP295381) | Clim_34_12S (PP295305) | Clim_34_COI (PP356612) | Clim_34_28S (PP295332) |

| Centruroides noxius | 6878 | Cnox_36_16S (PP295383) | Cnox_36_12S (PP295307) | Cnox_36_COI (PP356611) | Cnox_36_28S (PP295333) |

| Cnox_37_16S (PP295384) | Cnox_37_12S (PP295308) | Cnox_37_COI (PP356610) | Cnox_37_28S (PP295334) | ||

| Centruroides ornatus | 2338500 | Corn_03_16S (PP295350) | Corn_03_12S (PP295274) | Corn_03_COI (PP355195) | Corn_03_28S (PP295324) |

| Corn_04_16S (PP295351) | Corn_04_12S (PP295275) | Corn_04_COI (PP356609) | Corn_04_28S (PP295325) | ||

| KY981895 | KY981799 | – | KY982086 | ||

| MK479042 | MK478991 | MK479195 | MK479144 | ||

| Centruroides possanii | – | Cpos_10_16S (PP295357) | Cpos_10_12S (PP295281) | – | Cpos_10_28S (PP295314) |

| Cpos_07_16S (PP295354) | Cpos_07_12S (PP295278) | Cpos_07_COI (PP355196) | Cpos_07_28S (PP295312) | ||

| Cpos_08_16S (PP295355) | Cpos_08_12S (PP295279) | Cpos_08_COI (PP356608) | Cpos_08_28S PP295313 | ||

| Cpos_09_16S (PP295356) | Cpos_09_12S (PP295280) | Cpos_09_COI (PP356607) | Cpos_09_28S (PP295323) | ||

| Centruroides sculpturatus | 218467 | Cscu_35_16S (PP295382) | Cscu_35_12S (PP295306) | Cscu_35_COI (PP356606) | Cscu_35_28S (PP295331) |

| Centruroides sp. 1 | 3103037 | Csp1_23_16S (PP295370) | Csp1_23_12S (PP295294) | Csp1_23_COI (PP356604) | Csp1_23_28S (PP295311) |

| Centruroides sp. 2 | Csp2_11_16S (PP295358) | Csp2_11_12S (PP295282) | Csp2_11_COI (PP356603) | Csp2_11_28S (PP295327) | |

| Csp_14_16S (PP295361) | Csp_14_12S (PP295285) | Csp_14_COI (PP356605) | Csp_14_28S (PP295326) | ||

| Centruroides suffusus | 6881 | Csu_33_16S (PP295380) | Csu_33_12S (PP295304) | – | Csu_33_28S (PP295330) |

| Centruroides tecomanus1 | 1028682 | Cte1_12_16S (PP295359) | Cte1_12_12S (PP295283) | Cte1_12_COI (PP356602) | Cte1_12_28S (PP295315) |

| Cte1_17_16S (PP295364) | Cte1_17_12S (PP295288) | Cte1_17_COI (PP355197) | Cte1_17_28S (PP295320) | ||

| Cte1_18_16S (PP295365) | Cte1_18_12S (PP295289) | Cte1_18_COI (PP356601) | Cte1_18_28S (PP295318) | ||

| Centruroides tecomanus2 | Cte2_13_16S (PP295360) | Cte2_13_12S (PP295284) | Cte2_13_COI (PP356600) | Cte2_13_28S (PP295316) | |

| Cte2_15_16S (PP295362) | Cte2_15_12S (PP295286) | Cte2_15_COI (PP355198) | Cte2_15_28S (PP295317) | ||

| Table 4. Continued | |||||

| Species | NCBI:txid | 16S | 12S | COI | 28S |

| Cte2_19_16S (PP295366) | Cte2_19_12S (PP295290) | Cte2_19_COI (PP356599) | Cte2_19_28S (PP295319) | ||

| Cte2_20_16S (PP295367) | Cte2_20_12S (PP295291) | Cte2_20_COI (PP356598) | Cte2_20_28S (PP295321) | ||

| Cte2_21_16S (PP295368) | Cte2_21_12S (PP295292) | Cte2_21_COI (PP356597) | Cte2_21_28S (PP295322) | ||

| Centruroides tecomanus | MF134695 | – | MF134799 | MF134757 | |

| MK479053 | MK479002 | MK479206 | MK479156 | ||

| Mesomexovis sp. | – | Mesp_22_16S (PP295369) | Mesp_22_12S (PP295293) | Mesp_22_COI | Mesp_22_28S (PP295337) |

| Mesomexovis occidentalis | 1532992 | KM274362 | KM274216 | KM274800 | – |

| Mesomexovis spadix | 1532994 | KM274221 | KM274367 | KM274805 | KM274659 |

| Mesomexovis subcristatus | 1532995 | KM274368 | KM274222 | KM274806 | KM274660 |

| Thorellius cristimanus | 1533000 | Tcri_01_16S (PP295348) | Tcri_01_12S (PP295272) | – | Tcri_01_28S (PP295338) |

| Tcri_16_16S (PP295363) | Tcri_16_12S (PP295287) | – | Tcri_16_28S (PP295336) | ||

| Tcri_02_16S (PP295349) | Tcri_02_12S (PP295273) | – | Tcri_02_28S (PP295339) | ||

| Tcri_05_16S (PP295352) | Tcri_05_12S (PP295276) | – | Tcri_05_28S (PP295340) | ||

| KM274420 | KM274274 | KM274858 | KM274712 | ||

| KM274422 | KM274276 | KM274860 | KM274714 | ||

| Thorellius intrepidus | 1533001 | Tint_24__16S (PP295371) | Tint_24_12S (PP295295) | Tint_24_COI (PP355193) | Tint_24_28S (PP295341) |

| Tint_25_16S (PP295372) | Tint_25_12S (PP295296) | Tint_25_COI (PP356616) | Tint_25_28S (PP295342) | ||

| Tint_26_16S (PP295373) | Tint_26_12S (PP295297) | Tint_26_COI (PP356617) | Tint_26_28S (PP295343) | ||

| Tint_27_16S (PP295374) | Tint_27_12S (PP295298) | Tint_27_COI (PP355192) | Tint_27_28S (PP295344) | ||

| Tint_28_16S (PP295375) | Tint_28_12S (PP295299) | Tint_28_COI (PP356618) | Tint_28_28S (PP295345) | ||

| Tint_29_16S (PP295376) | Tint_29_12S (PP295300) | Tint_29_COI (PP356619) | Tint_29_28S (PP295346) | ||

| KM274424 | KM274278 | KM274862 | – | ||

| KM274425 | KM274279 | KM274863 | KM274717 | ||

| Vaejovis sp. | – | Vasp_32_16S (PP295379) | Vasp_32_12S (PP295303) | Vasp_32_COI (PP356620) | Vasp_32_28S (PP295347) |

| Vaejovis carolinianus | 33322 | KM274289 | KM274143 | KM274727 | KM274581 |

| Vaejovis pequeno | 1532951 | KM274293 | KM274147 | KM274731 | KM274585 |

| Vaejovis rossmani | 1532952 | KM274294 | KM274148 | KM274732 | KM274586 |

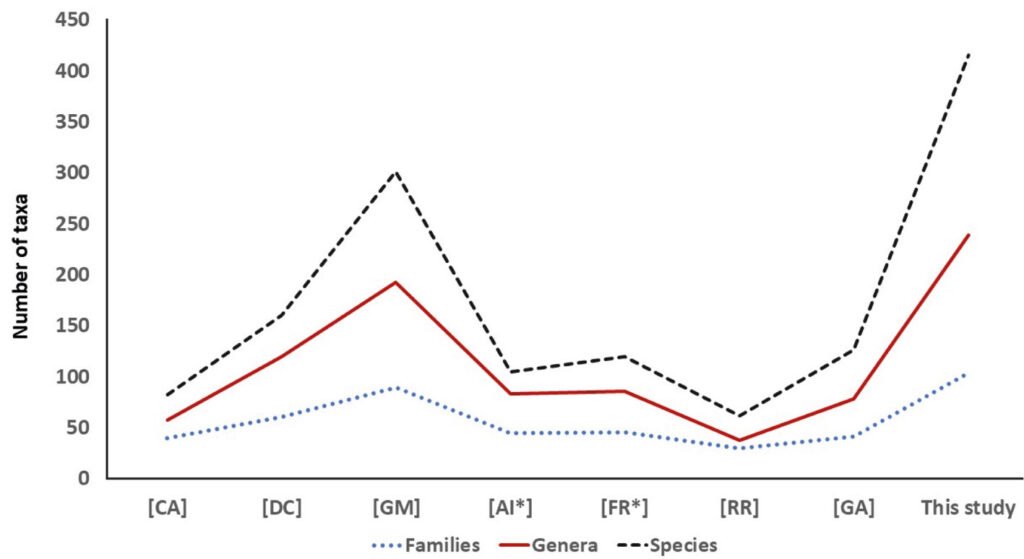

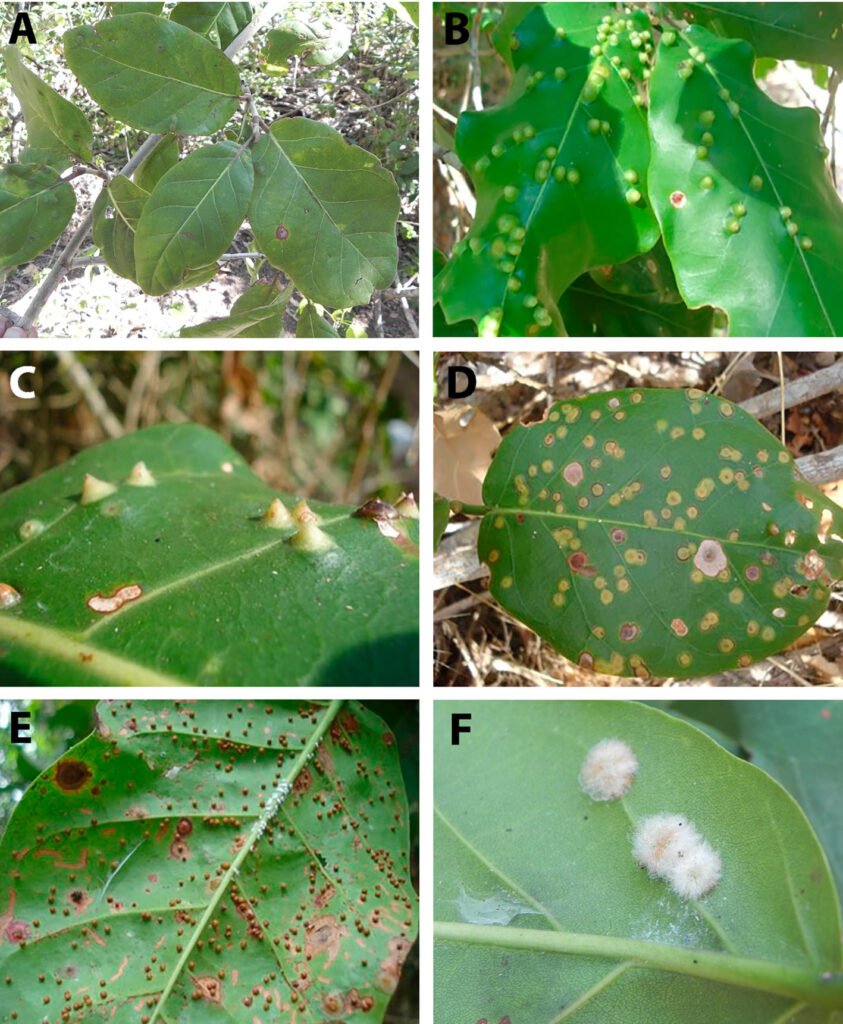

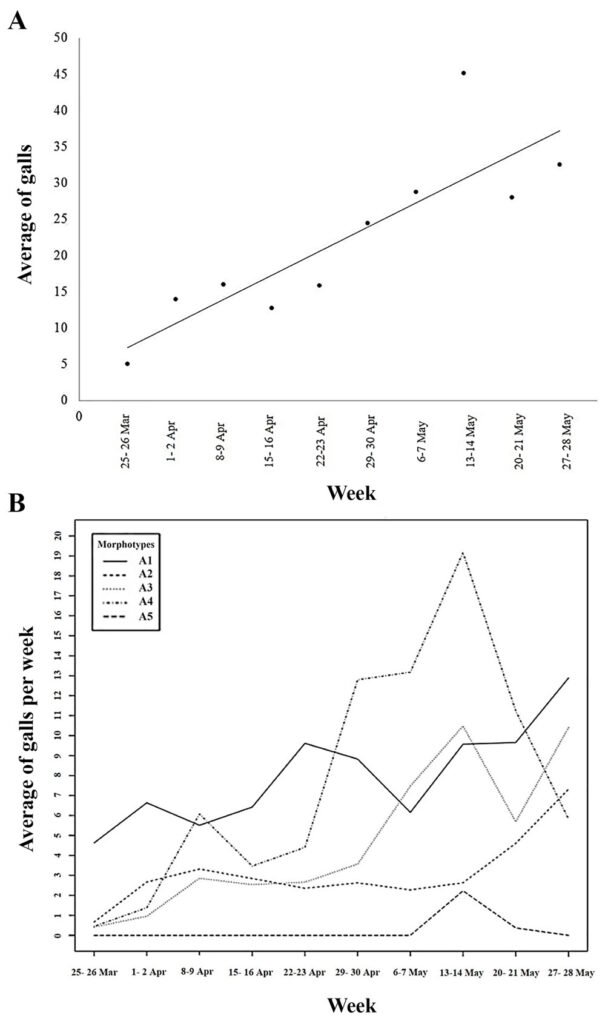

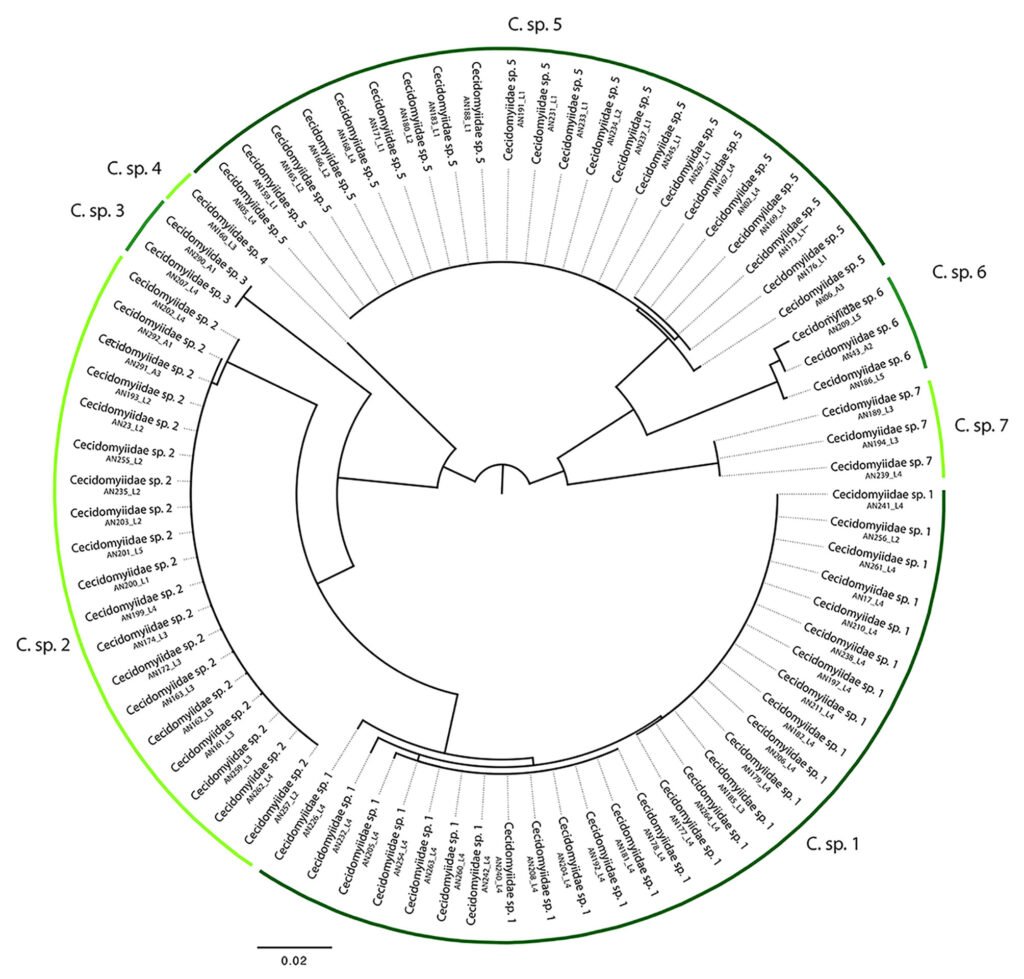

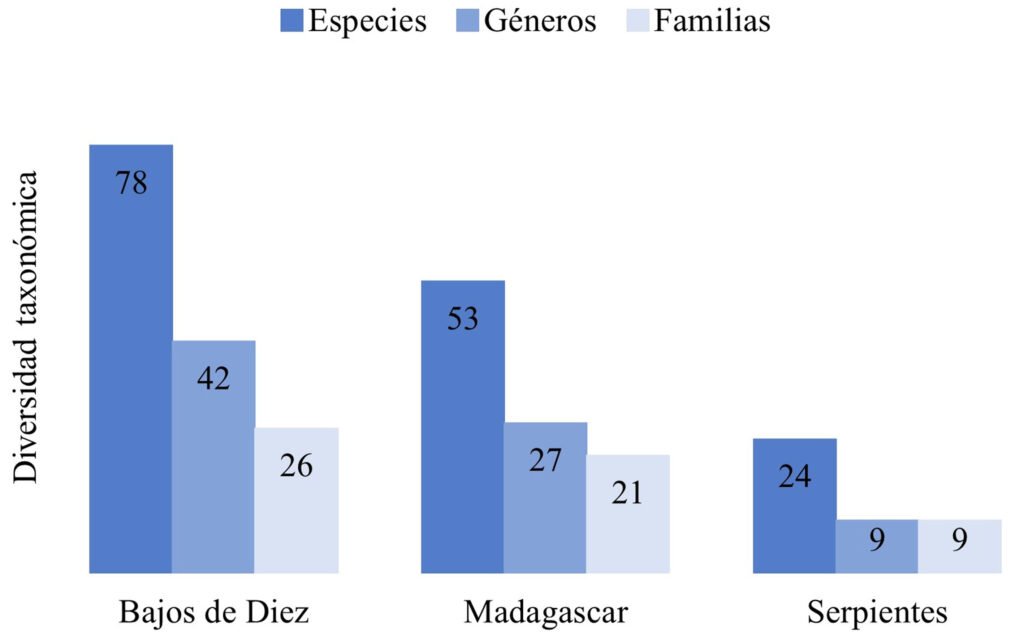

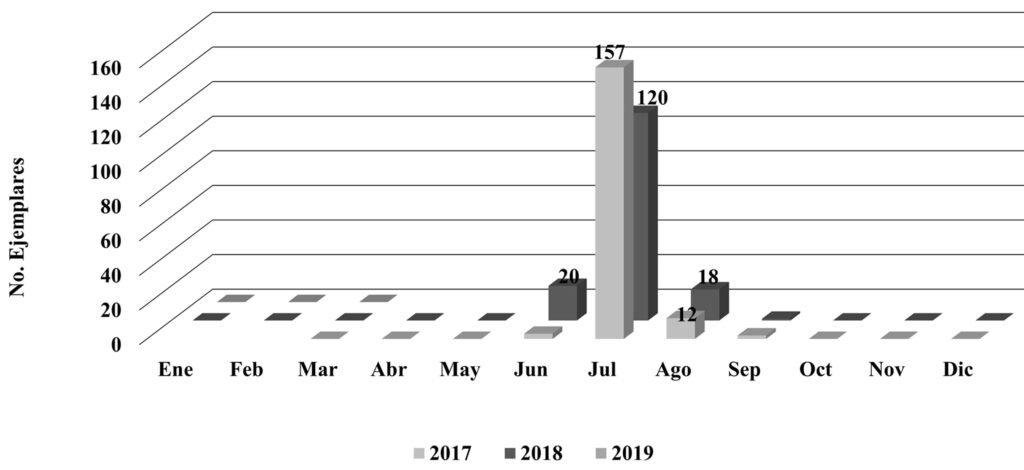

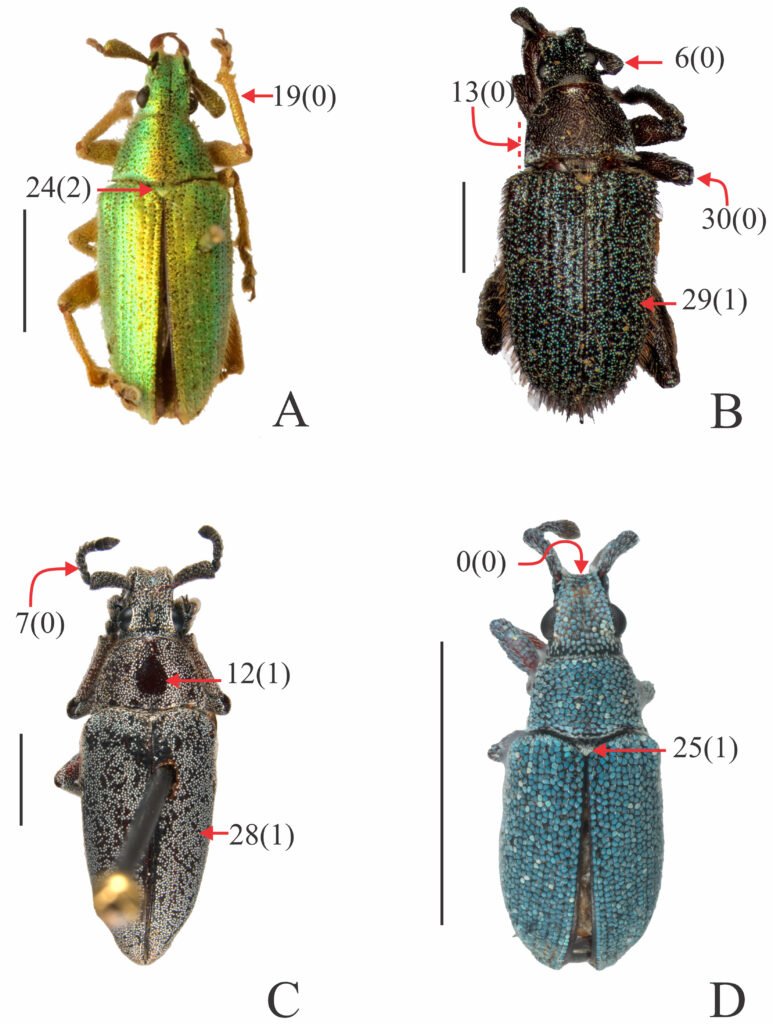

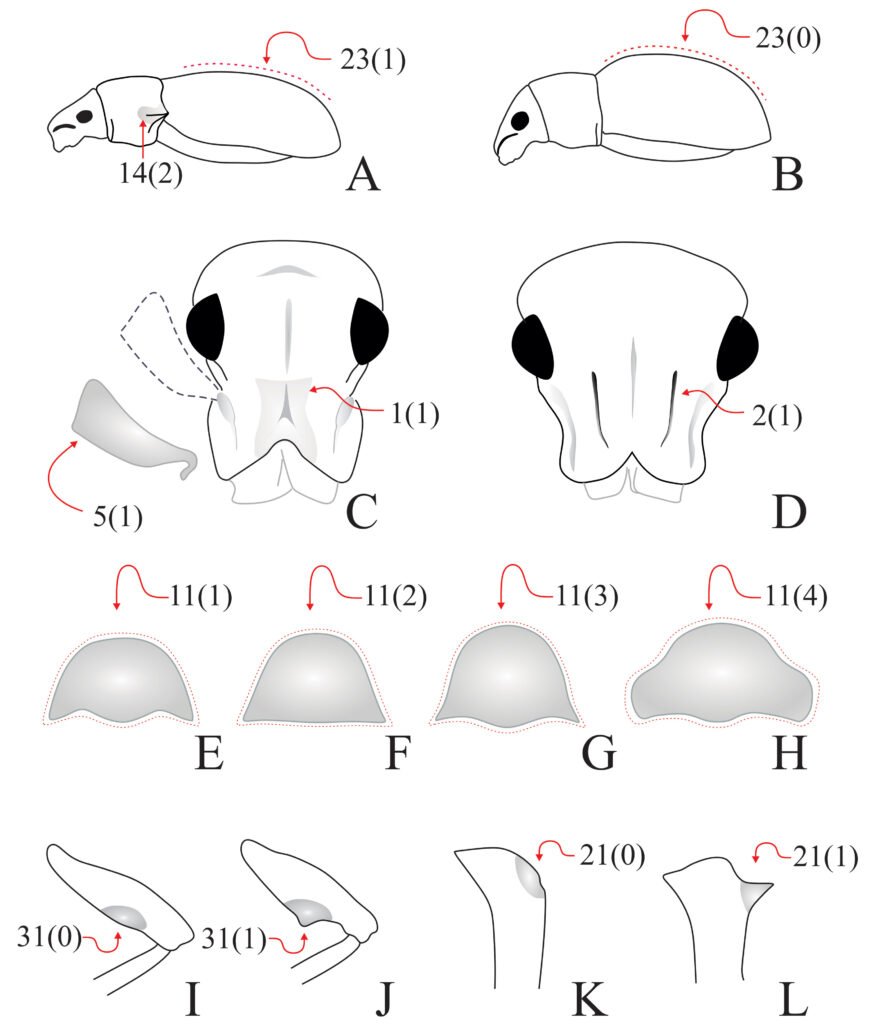

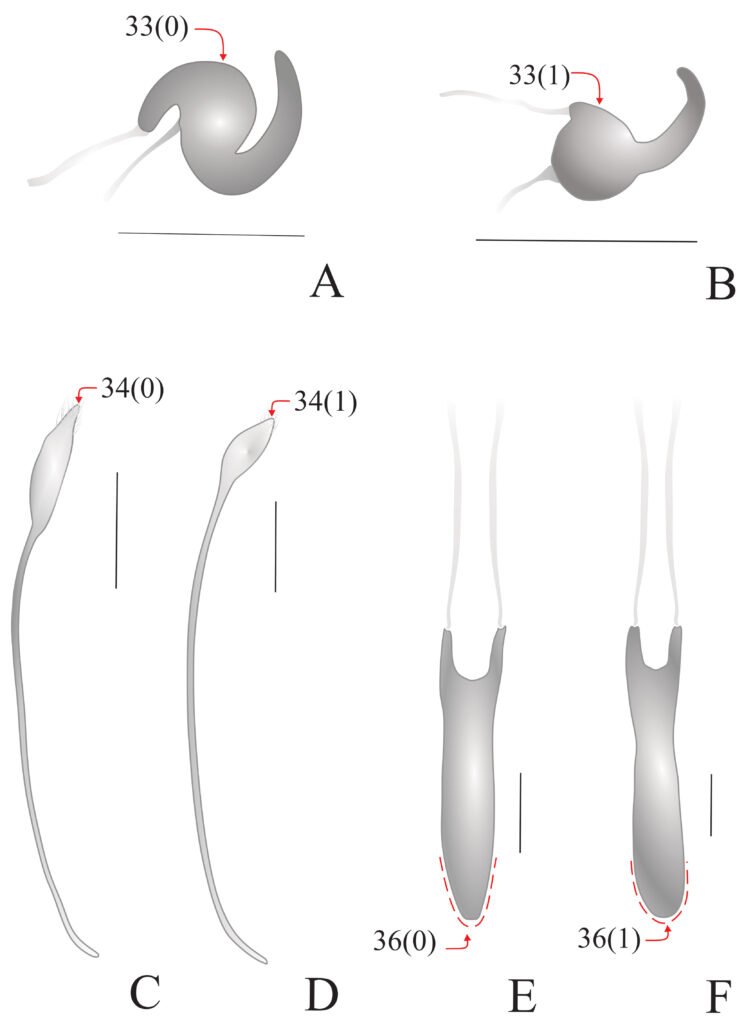

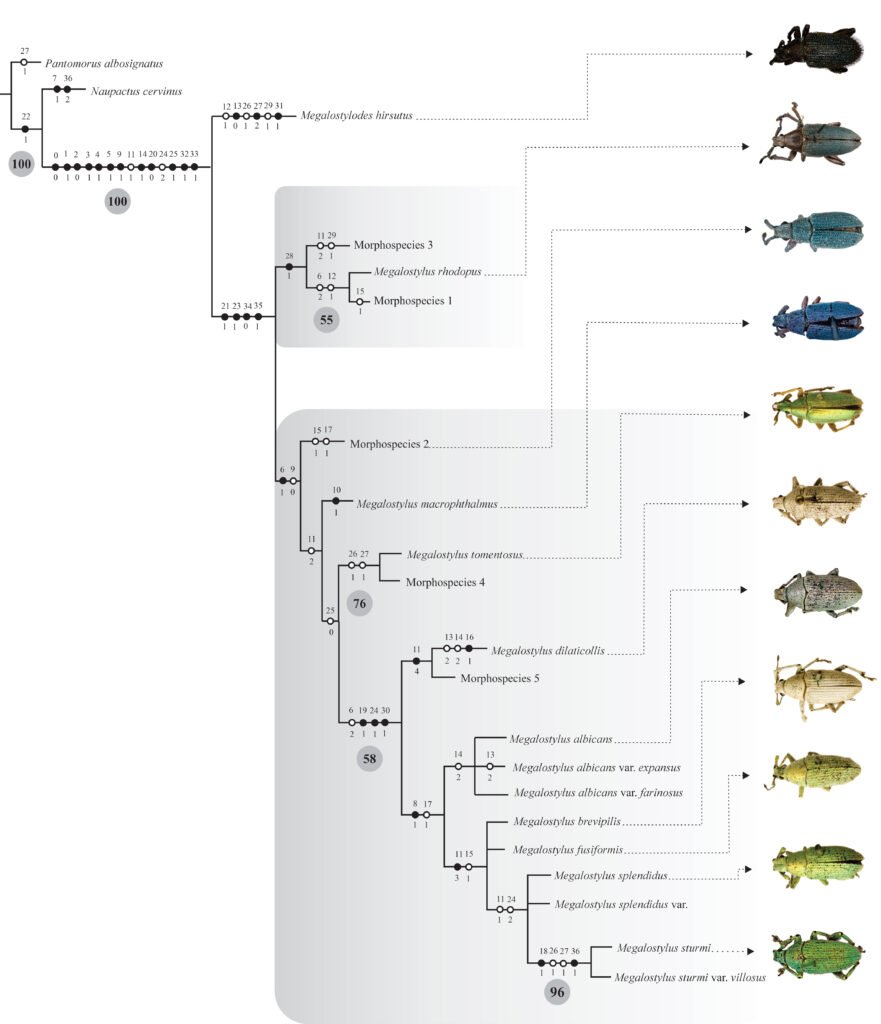

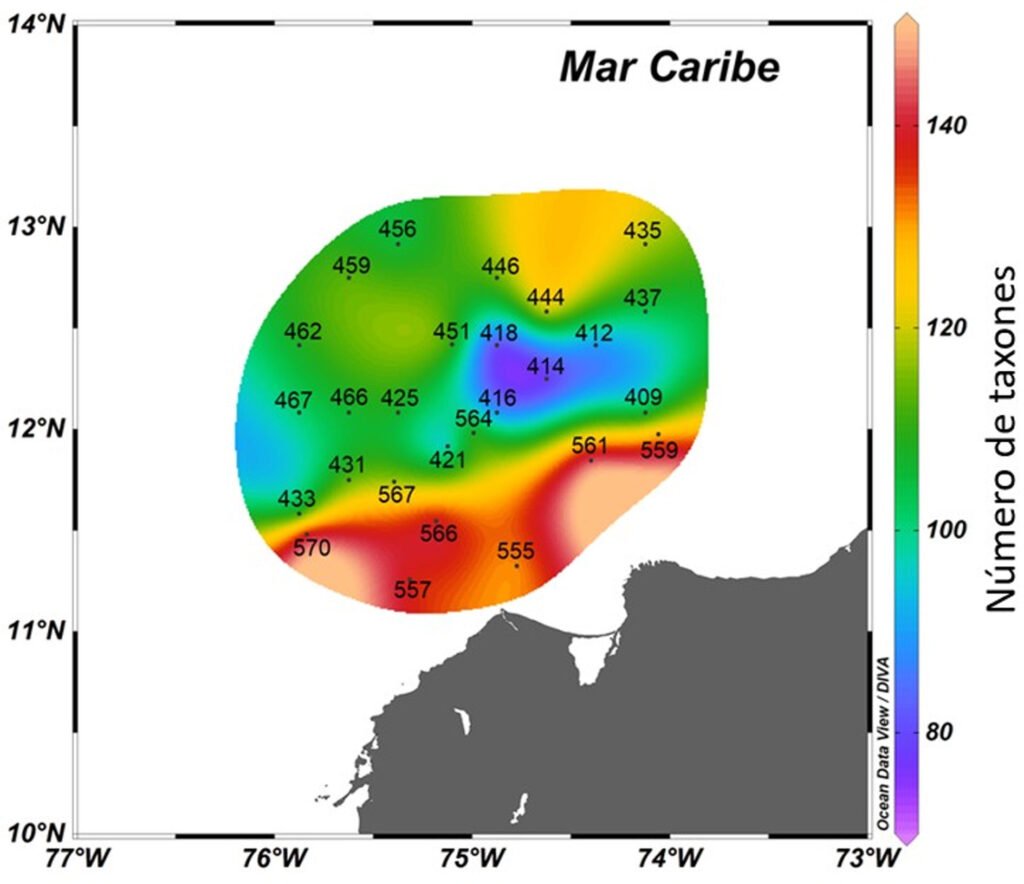

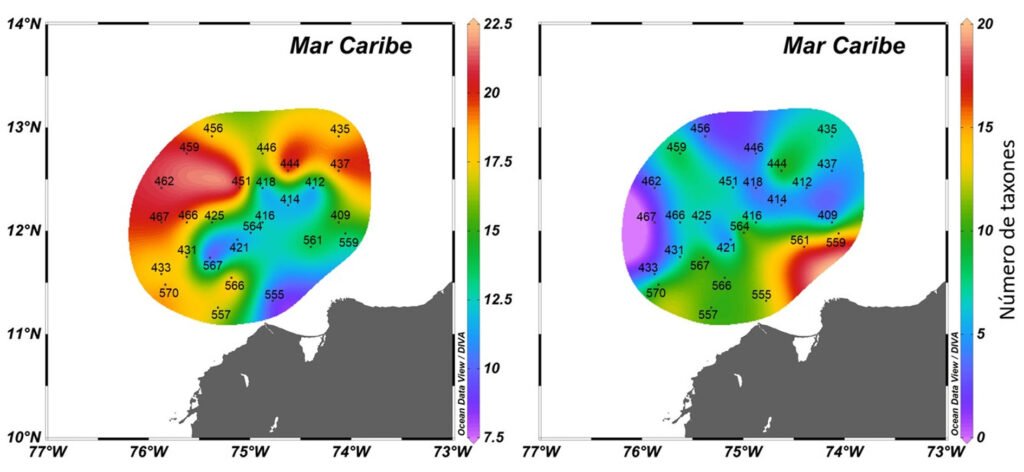

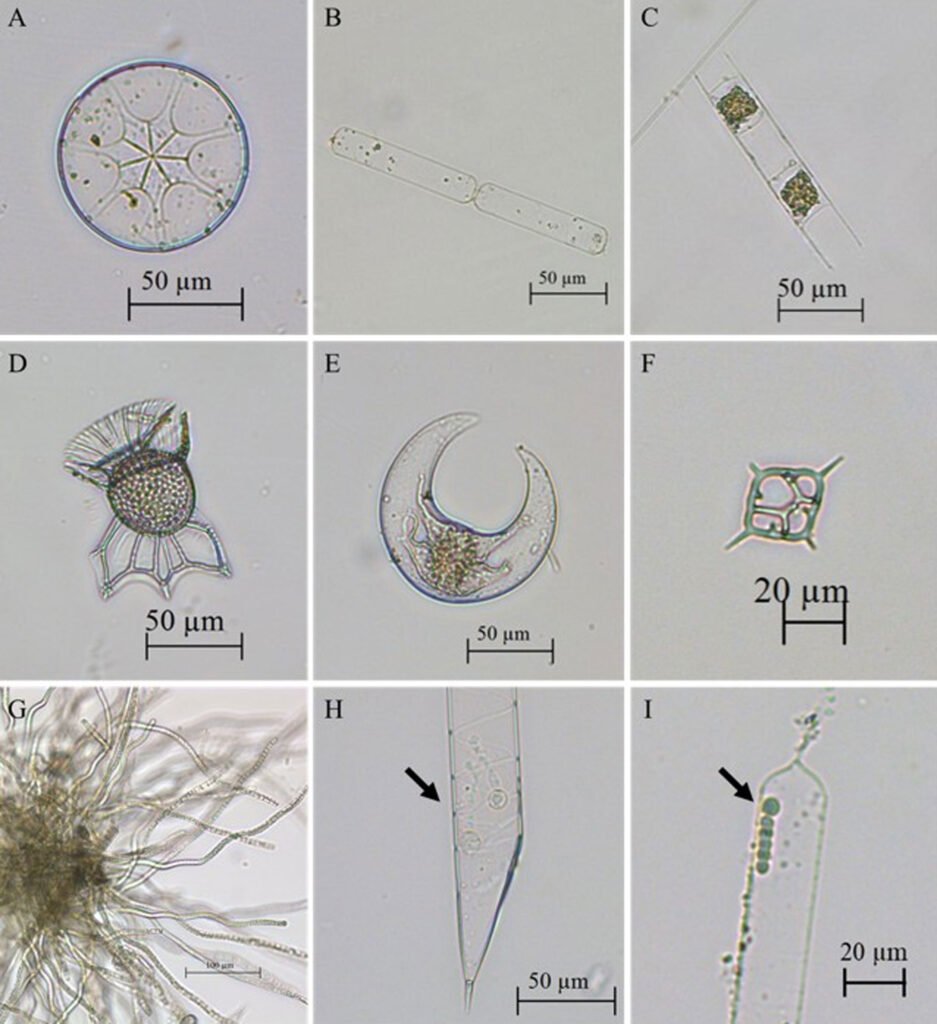

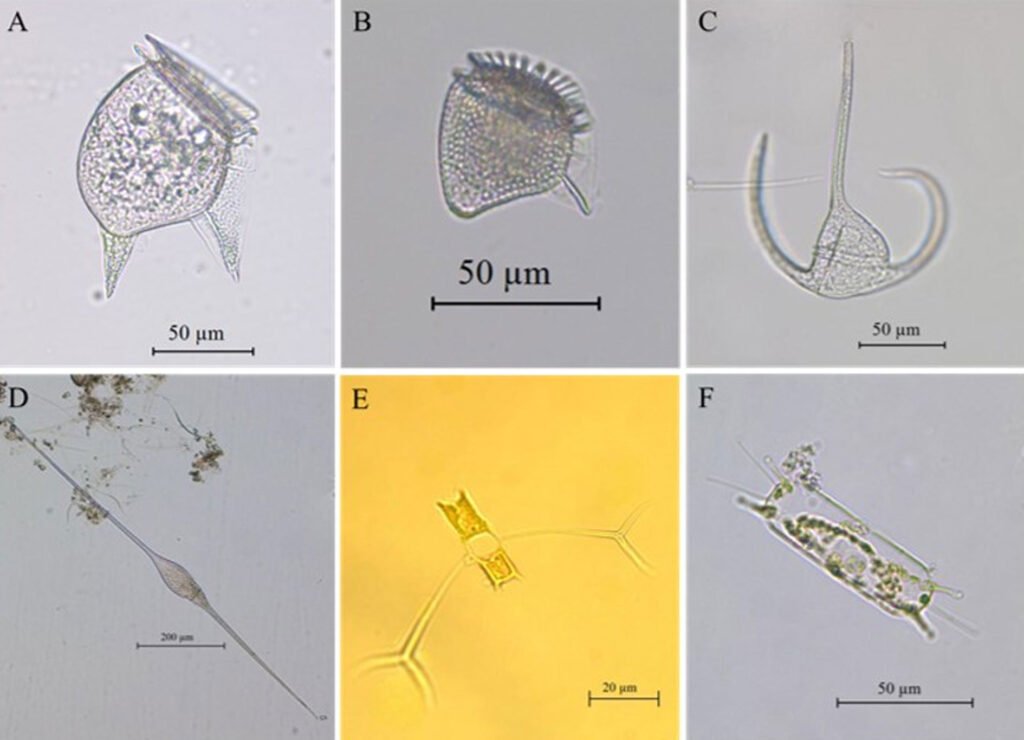

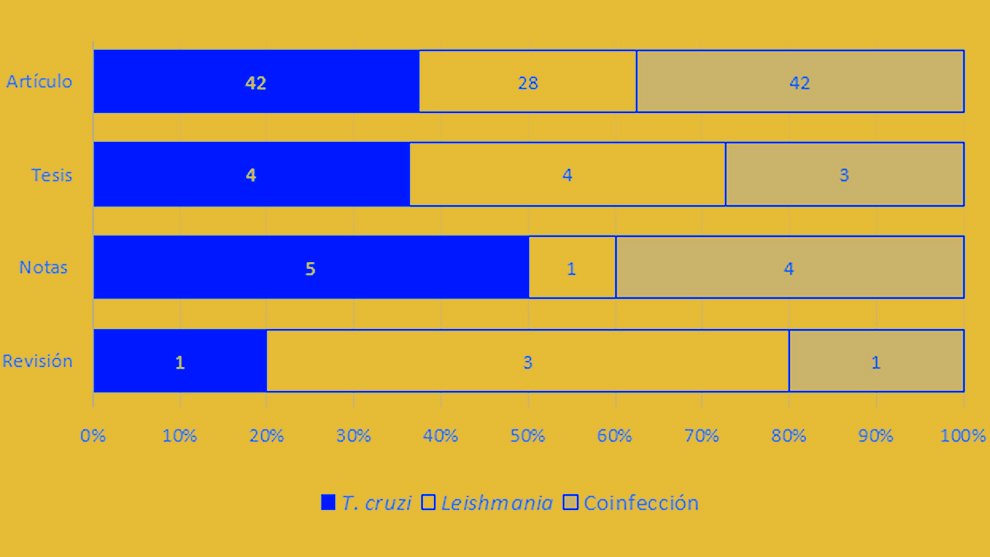

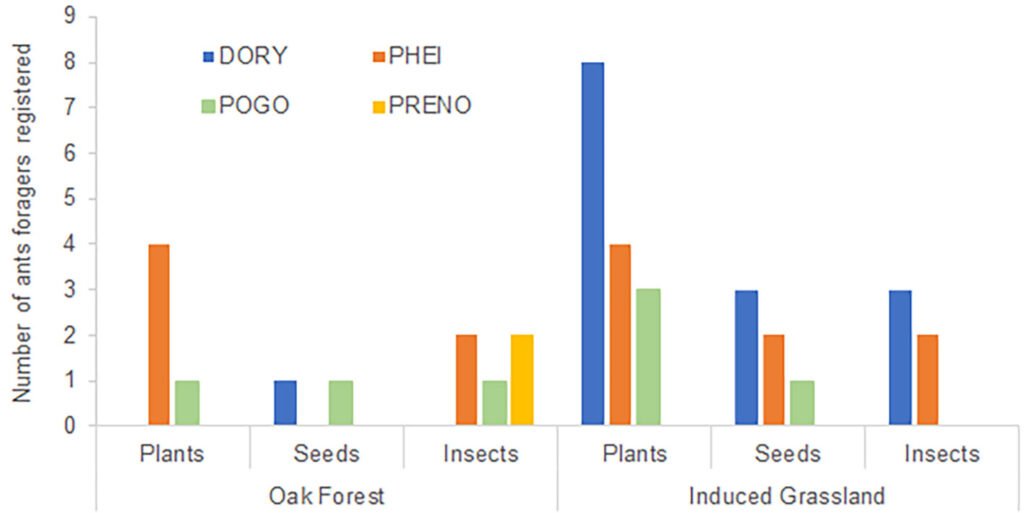

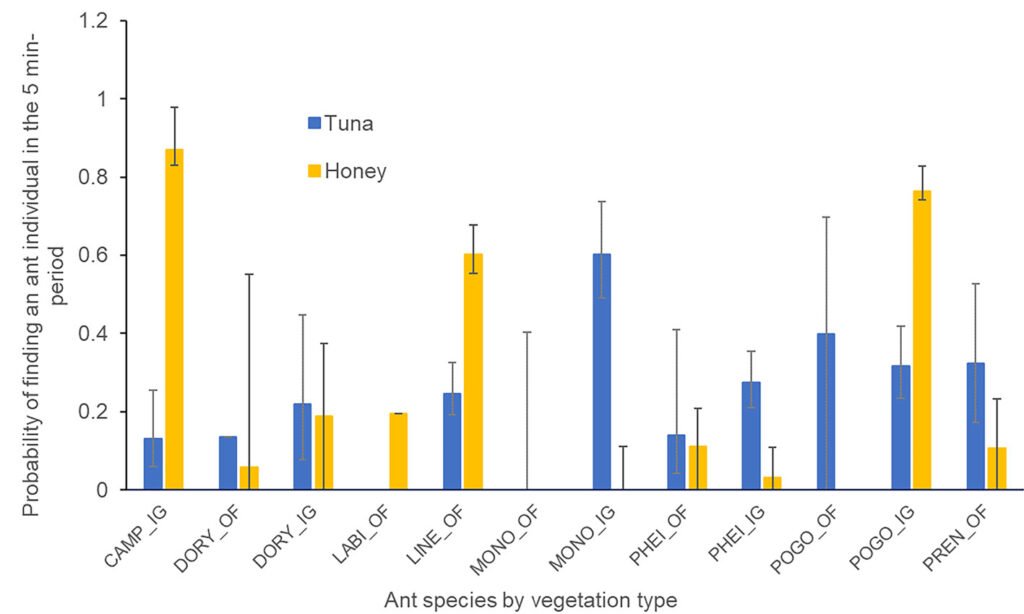

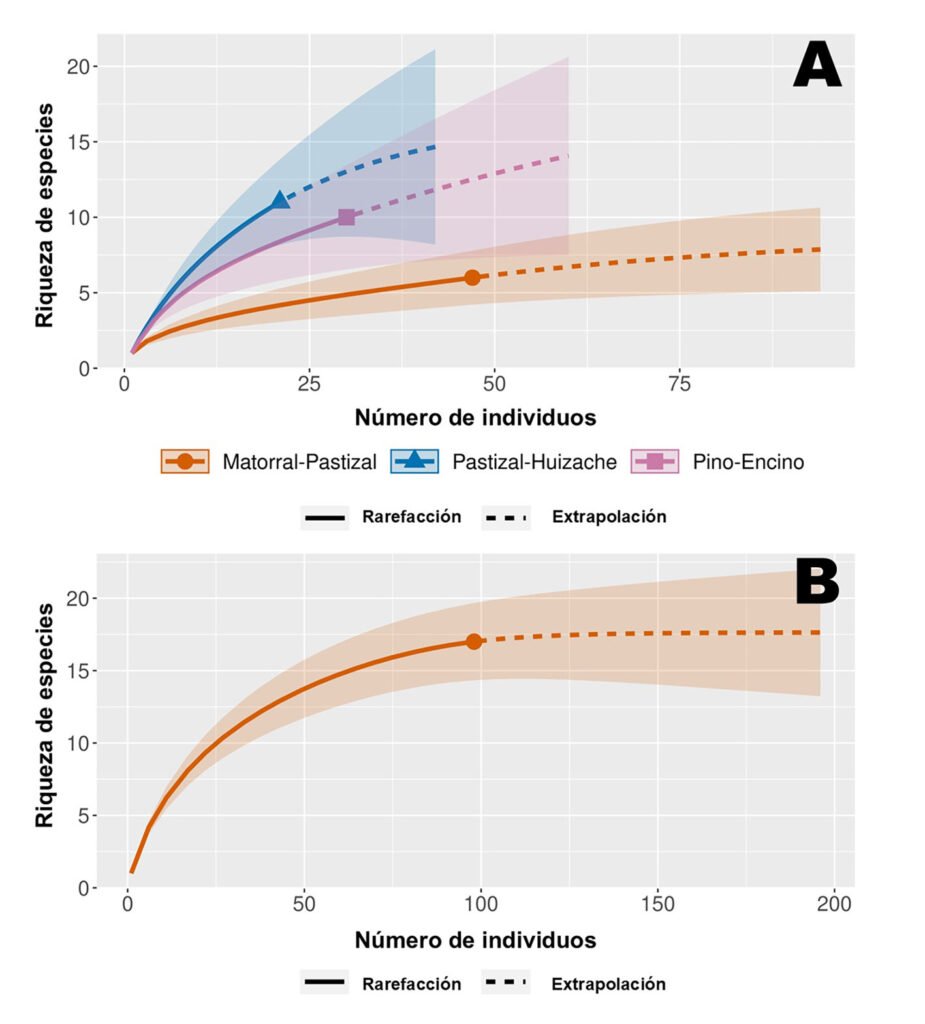

Table 5